Arthur (Or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire)

| Arthur or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 10 October 1969 | |||

| Recorded | May–July 1969 | |||

| Studio | Pye, London | |||

| Genre | Rock | |||

| Length | 49:17 | |||

| Label | Pye (UK) · Reprise (US) | |||

| Producer | Ray Davies | |||

| The Kinks chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Arthur | ||||

| ||||

Arthur or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire, often referred to simply as Arthur, is the seventh studio album by the English rock band the Kinks, released on 10 October 1969. It was the first Kinks album to feature bassist John Dalton, who replaced Pete Quaife after the former’s departure. Kinks frontman Ray Davies constructed the concept album as the soundtrack to a Granada Television play and developed the storyline with novelist Julian Mitchell; the television programme was never produced. The rough plot revolved around Arthur Morgan, a carpet-layer, who was based on Ray and guitarist Dave Davies' brother-in-law Arthur Anning. A stereo version was released internationally with a mono version being released in the UK, but not in the US.

The album was met with poor sales but nearly unanimous acclaim, especially among the American music press. Although Arthur and its first two singles, "Drivin'" and "Shangri-La", failed to chart in the UK, the Kinks returned to the Billboard charts after a two-year absence[1] with "Victoria", the lead single in the US, peaking at number 62. The album itself reached number 105 on the Billboard Top LPs chart, their highest position for three years. Arthur paved the way for the further success of the Kinks' 1970 comeback album Lola Versus Powerman and the Moneygoround, Part One.[2]

Background

[edit]British production company Granada TV approached Ray Davies in early January 1969, expressing interest in developing a film or play for television. Davies was to collaborate with writer Julian Mitchell on the "experimental" programme,[3] with a soundtrack by the Kinks to be released on an accompanying LP.[3] Agreements were finalised on 8 January, and the project was revealed at a press release on 10 March. Separately, the Kinks began work on the programme's companion record, entitled Arthur (Or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire).

Development of Arthur occurred during a rough period for the band, due to the commercial failure of their previous album The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society and the subsequent single, "Plastic Man", as well as the departure of founding member and bassist Pete Quaife.[4] In early 1969, Quaife had told the band he was leaving, though the other members did not take the remark seriously because Quaife had left the band in 1966 after breaking his leg in a car accident, only to have a change of heart and rejoin shortly afterwards.[5] When an article in the New Musical Express mentioned Maple Oak, the band he had formed without the rest of the Kinks' knowledge, Davies unsuccessfully asked Quaife to return for the upcoming sessions of Arthur.[6] Bassist John Dalton, who had briefly replaced Quaife when the latter had quit three years prior, was asked by drummer Mick Avory to rejoin the band.[5]

Ray Davies travelled to United Recording Studios in Los Angeles on 11 April 1969, to produce American band the Turtles' LP Turtle Soup with engineer Chuck Britz.[7] While in Los Angeles, Davies helped negotiate an end to the concert ban placed on the Kinks by the American Federation of Musicians in 1965.[7] Although neither the Kinks nor the union gave a specific reason for the ban, at the time it was widely attributed to their rowdy on-stage behaviour.[8] After negotiations with Davies, the Federation allowed the group to return to touring in America. Once the main sessions for the Turtles LP were completed, Davies returned to England.

While Davies was abroad, the other members of the band had been rehearsing and practising for the upcoming album, as well as lead guitarist Dave Davies' solo album, nicknamed A Hole in the Sock of.[3][7] When Ray returned, the Kinks regrouped at his house in Borehamwood, Hertfordshire, to rehearse Arthur.[7]

Recording

[edit]The group turned to the recording proper on 1 May 1969.[7] The first tracks worked on were "Drivin'", intended as their next single release, and "Mindless Child of Motherhood", written by Dave Davies (the latter would eventually be used as the B-side to "Drivin'", and was not included on the LP). The Kinks began a two-week series of focused sessions on 5 May, laying down an early version of the entire Arthur album. Recording was interrupted when the Kinks travelled to Beirut, Lebanon on 17 May to play three dates at the Melkart Hotel;[9] sessions for Arthur resumed the day after their return, and most of the recording for the album was finished by the end of the month.[9] Mixing and dubbing began in early June, with arranger Lew Warburton handling string overdubs.[10] The Kinks played a few small gigs in England throughout the remainder of the month, but devoted most of their time to finishing Dave Davies' solo album.[10]

Writing for the TV play progressed through May and June, and on 15 June mixing for Dave Davies' solo LP was completed (tapes for this record were eventually delivered to Pye and Reprise Records, although it never saw official release).[9] A press release announced that the Arthur LP was scheduled for a late July release.[9] As Davies and Mitchell completed their script, the Arthur TV play began to crystallise, and British filmmaker Leslie Woodhead was assigned the role of director. By early September production was scheduled to begin, with a planned broadcast of late September, but these plans were continually delayed.[11] As problems with the TV play got progressively worse—and, consequently, distracted the Kinks from completing the post-production of the album—the release dates for both projects were pushed further and further back.[3][9] In early October Ray Davies moved from Borehamwood back to his old family home on Fortis Green, in Muswell Hill, and travelled to Los Angeles, where he delivered the tapes to Reprise for Arthur's American release.[12] The album's release date was set for 10 October,[12] and the Kinks began gearing up for an upcoming US tour to support the album, for which they would depart on 17 October.[13] Shooting for the TV play was set for 1 December. Roy Stonehouse was hired as a designer, and the casting was completed, but the show was cancelled at the last minute when the producer was unable to secure financial backing.[14] Davies and Mitchell were frustrated at an entire year's work wasted: Doug Hinman said Davies witnessed "his grand artistic visions once again dashed by bureaucracy and internal politics".[15]

Story and theme

[edit]The story is partially inspired by the Davies brothers' older sister Rose, who emigrated to Australia in 1964 with her husband Arthur Anning.[17] Her departure devastated Ray Davies, and it inspired him to write the song "Rosy Won't You Please Come Home", included on the 1966 album Face to Face.[17] The lead character in the album, the fictional Arthur Morgan—modelled after Anning—is a carpet layer whose family's plight in the opportunity-poor setting of post-war England is depicted.[18][17] Writer Julian Mitchell detailed the story line and characters in depth, explaining in the liner notes for the album's LP release:

Arthur Morgan ... lives in a London suburb in a house called Shangri-La, with a garden and a car and a wife called Rose and a son called Derek who's married to Liz, and they have these two very nice kids, Terry and Marilyn. Derek and Liz and Terry and Marilyn are emigrating to Australia. Arthur did have another son, called Eddie. He was named after Arthur's brother, who was killed in the battle of the Somme. Arthur's Eddie was killed, too—in Korea.[18]

Davies later commented in his autobiography, X-Ray, that Anning later "told me that he ... knew it [Arthur] had been partly inspired by him ... [it] reminded him of home ... I told Arthur that I felt guilty for using him as a subject for a song, but he shrugged off my apology, saying that he was flattered."[19] With an underlying theme of nostalgia,[20] the songs describe the England Arthur once knew[21] ("Victoria", "Young and Innocent Days"), the promise of life in Australia for one of his sons ("Australia"), the emptiness of his superficially comfortable life in his home ("Shangri-La"), the resolve of the British people during the Second World War ("Mr. Churchill Says"), the privations that marked the austerity period after the war ("She's Bought a Hat Like Princess Marina"), and the death of his brother in World War I ("Yes Sir, No Sir", "Some Mother's Son").[22][17]

Release

[edit]Arthur (Or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire) was released in the UK and US on 10 October 1969.[23] It was the last Kinks album to be released in mono, and the mono edition was not released in the US. The album set the stage for the Kinks' return to touring the United States in late 1969,[8] and paved the way for even greater commercial success with the hit song "Lola" in 1970.[2]

Singles and chart performance

[edit]While the sessions for Arthur (Or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire) were nearing completion in June 1969, the track "Drivin'" was released as a single in the UK, backed with "Mindless Child of Motherhood". For the first time since their breakthrough in 1964, a Kinks single failed to make an impression on the UK charts[24]—Johnny Rogan notes that "This was the first of two pilot singles for ... Arthur and its failure did not augur well".[25] The group followed with another single in September, "Shangri-La", which again failed to chart in the UK. As with Village Green, the album itself failed to chart when released in October.[24]

In the US, "Victoria" was the lead single, backed with the album track "Brainwashed", and was released the same week as the LP. The single reached number 62 on the Billboard Hot 100—their highest position since their Top 20 hit "Sunny Afternoon" in 1966. The success of the single led to its release in the UK; backed with "Mr. Churchill Says", it reached a peak of number 30.[26] Arthur itself was a moderate commercial success in the US, where it peaked at number 105, and remained on the charts for 20 weeks.[27]

Promotion

[edit]Reprise Records, the Kinks' US label, devised an elaborate, multi-levelled promotional campaign for Arthur in early 1969. The most famous branch of the programme involved a promo package entitled God Save the Kinks. The set featured various items, including a consumer's guide to the band's albums, a bag of "grass" from the "Daviesland village green", and an LP entitled Then, Now and Inbetween.[13] The set was accompanied by a positive letter from Hal Halverstadt of creative services at Warner/Reprise, part of which read, "... [We are led] to believe that the Kinks may not have had it at all ... The Kinks are to be supported, encouraged, cheered. And saved."[13] The campaign was officially launched on 3 July, at a meeting between Ray Davies and Reprise executives in Burbank, California.[28] Reprise considered seeding false stories in the press to create an "outlaw" image for the group as part of the campaign, including pieces about marijuana possession and income tax evasion.[29] Ray called the idea "mad", and the programme was dropped. Several pieces were used in the press kit for Arthur's release, with titles including "English Pop Group Arrested on Rape Rap".[29]

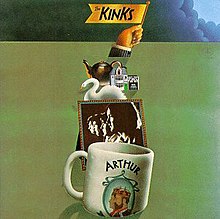

Packaging and liner notes

[edit]Artwork for Arthur was created by Bob Lawrie.[18] The album was packaged in a gatefold sleeve, and included a shaped insert depicting Queen Victoria (holding a house containing Arthur Morgan), with lyrics on the reverse. Liner notes in the UK were written by Geoffrey Cannon and Julian Mitchell; in the US, notes by rock critic John Mendelsohn replaced Cannon's.[30]

Critical reception

[edit]The album was critically acclaimed at the time of release, especially in the US rock press.[31] It was favourably compared to Tommy by the Who, released earlier in the year.[31] In Rolling Stone, Arthur was spotlighted in its lead section, with back-to-back reviews by Mike Daly and Greil Marcus.[29] Daly called it "an album that is a masterpiece on every level: Ray Davies' finest hour, the Kinks' supreme achievement".[32] Marcus also praised the album, calling it "Less ambitious than Tommy, and far more musical ... Arthur is by all odds the best British album of 1969. It shows that Pete Townshend still has worlds to conquer and that the Beatles have a lot of catching up to do."[33] A review by Sal Imam ran in Boston's Fusion magazine read that "If Tommy was the greatest rock opera, then Arthur most surely is the greatest rock musical."[29][31] Writing in his Consumer Guide column of The Village Voice, Robert Christgau gave the record a positive review, saying that although Ray Davies' lyrics could get "petulant and preachy at times", the album featured "excellent music and production".[34]

Reception in the UK was not as warm, although reviews were still generally positive.[31] Disc & Music Echo commented that "Arthur works as a complete score because it is basic and simple and pleasing to the ear, and powerfully conjures up pictures in the eye."[23] Melody Maker seconded Mike Daly's comments in Rolling Stone, again calling it "Ray Davies' finest hour", and adding that it was "beautifully British to the core".[23] Doug Hinman later commented on the album's reception in Britain: "In the British music press there [was] less celebration, and coverage [was] relatively routine, though everyone saw the rock opera angle."[31]

Reappraisal

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| The Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Uncut | |

Today the album receives generally positive reviews. Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic said Arthur was "one of the most effective concept albums in rock history, as well as one of the best and most influential British pop records of its era",[22] and in 2003 Matt Golden of Stylus Magazine called it "the best rock opera ever".[21] Switch magazine included Arthur on their "100 Best Albums of the 20th Century" in 1999,[citation needed] and in 2003 Mojo featured the album on their list of the "Top 50 Most Eccentric Albums".[citation needed]

The album is included in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[39]

Track listing

[edit]All tracks are written by Ray Davies, except where noted

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Victoria" | 3:40 |

| 2. | "Yes Sir, No Sir" | 3:46 |

| 3. | "Some Mother's Son" | 3:25 |

| 4. | "Drivin'" | 3:21 |

| 5. | "Brainwashed" | 2:34 |

| 6. | "Australia" | 6:46 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Shangri-La" | 5:20 |

| 2. | "Mr. Churchill Says" | 4:42 |

| 3. | "She's Bought a Hat Like Princess Marina" | 3:07 |

| 4. | "Young and Innocent Days" | 3:21 |

| 5. | "Nothing to Say" | 3:08 |

| 6. | "Arthur" | 5:27 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13. | "Plastic Man" (mono) | 3:04 | |

| 14. | "King Kong" (mono) | 3:23 | |

| 15. | "Drivin'" (mono) | 3:12 | |

| 16. | "Mindless Child of Motherhood" (mono) | Dave Davies | 3:16 |

| 17. | "This Man He Weeps Tonight" (mono) | Dave Davies | 2:42 |

| 18. | "Plastic Man" (stereo) | 3:04 | |

| 19. | "Mindless Child of Motherhood" (stereo) | Dave Davies | 3:16 |

| 20. | "This Man He Weeps Tonight" | Dave Davies | 2:42 |

| 21. | "She's Bought a Hat Like Princess Marina" (mono) | 3:07 | |

| 22. | "Mr. Shoemaker's Daughter" | Dave Davies | 3:08 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13. | "Plastic Man" | 3:04 | |

| 14. | "This Man He Weeps Tonight" | Dave Davies | 2:43 |

| 15. | "Mindless Child of Motherhood" | Dave Davies | 3:09 |

| 16. | "Creeping Jean" | Dave Davies | 3:19 |

| 17. | "Lincoln County" | Dave Davies | 3:13 |

| 18. | "Hold My Hand" | Dave Davies | 3:21 |

| 19. | "Victoria" (studio recording for the BBC) | 3:36 | |

| 20. | "Mr. Churchill Says" (studio recording for the BBC) | 3:38 | |

| 21. | "Arthur" (studio recording for the BBC) | 3:16 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13. | "Plastic Man" | 3:03 | |

| 14. | "This Man He Weeps Tonight" | Dave Davies | 2:39 |

| 15. | "Drivin'" (alternative stereo mix) | 3:16 | |

| 16. | "Mindless Child of Motherhood" | Dave Davies | 3:10 |

| 17. | "Hold My Hand" (alternative stereo mix) | Dave Davies | 3:15 |

| 18. | "Lincoln County" | Dave Davies | 3:23 |

| 19. | "Mr. Shoemaker's Daughter" | Dave Davies | 3:07 |

| 20. | "Mr. Reporter" | 3:36 | |

| 21. | "Shangri-La" (backing track) | 5:28 |

Personnel

[edit]Credits adapted from the liner notes of Arthur.[18]

- The Kinks

- Ray Davies – lead and backing vocals, rhythm guitar, keyboards (harpsichord and piano), production

- Dave Davies – lead guitar, backing vocals, co-lead vocals on "Australia" and "Arthur", lead vocals on his own tracks

- John Dalton – bass guitar, backing vocals

- Mick Avory – drums, percussion

- Bonus tracks

- Pete Quaife – bass guitar, backing vocals on tracks: "Plastic Man", "King Kong", "This Man He Weeps Tonight", "Lincoln County", "Hold My Hand" and "Creeping Jean"

- Production

- Lew Warburton – horn and string arrangements

- Andrew Hendriksen – engineering

- Brian Humphries – engineering on "Drivin'"

- Bob Lawrie – album art

- Austin Sneller – credited as "album 'tester'"

Charts

[edit]Weekly charts

[edit]| Year | Billboard | Cash Box | Record World |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | 105[27] | 53[40] | 50[41] |

Singles

[edit]| Year | Title | Peak chart positions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK | US | NL | ||

| 1969 | "Drivin'" | — | — | — |

| "Shangri-La" | — | — | 24[42] | |

| "Victoria" | 30[26] | 62[26] | — | |

| "—" denotes the release failed to chart. | ||||

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Miller 2003, p. 133

- ^ a b Rogan 1998, pp. 65–75

- ^ a b c d Hinman 2004, p. 124

- ^ Hasted 2011, pp. 130–133.

- ^ a b Hinman 2004, p. 126

- ^ Hasted 2011, pp. 136–137.

- ^ a b c d e Hinman 2004, pp. 128–129

- ^ a b Alterman 1969

- ^ a b c d e Hinman 2004, pp. 126–130

- ^ a b Hinman 2004, p. 129

- ^ Hinman 2004, p. 131

- ^ a b Hinman 2004, pp. 130–135

- ^ a b c Savage 1984, p. 110

- ^ Savage 1984, p. 114

- ^ Hinman 2004, p. 136

- ^ Davies, Ray. "Arthur" lyrics. Hill & Range Songs (US, 1969)

- ^ a b c d Kitts 2007, p. 131

- ^ a b c d Mitchell, Julian; Geoffrey Cannon (1969). Arthur UK liner notes

- ^ Davies 1995, p. 211

- ^ Marten & Hudson 2007, pp. 101–102

- ^ a b Golden, Matt (1 September 2003). "On Second Thought: The Kinks – Arthur (or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire)". Stylus Magazine. Archived from the original on 5 February 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ^ a b c Erlewine, Stephen. "Arthur (Or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire)". AllMusic. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ^ a b c Hinman 2004, p. 133

- ^ a b Rogan 1998, pp. 21–22

- ^ Rogan 1998, p. 21

- ^ a b c Rogan 1998, pp. 20–23

- ^ a b "Billboard 200". Billboard. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ Hinman 2004, p. 130

- ^ a b c d Hinman 2004, p. 132

- ^ Mitchell, Julian; Mendelssohn, John (1969). Arthur US liner notes

- ^ a b c d e Hinman 2004, pp. 132–133

- ^ Daly & Marcus 1969

- ^ Admin, G. M. (30 November 2016). "Kinks, 'Arthur' (11/01/69)". GreilMarcus.net.

- ^ Christgau, Robert. "Consumer Guide: The Kinks". Robertchristgau.com. Village Voice. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ^ Powers, Ann. "Arthur". Blender. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2007). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0857125958.

- ^ The Rolling Stone Album Guide. Random House. 1992. pp. 401, 402.

- ^ "Kinks Klassics". Uncut. No. 88. September 2004. p. 62.

- ^ Robert Dimery; Michael Lydon (7 February 2006). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die: Revised and Updated Edition. Universe. ISBN 0-7893-1371-5.

- ^ "Cashbox Top 100 Albums". Cash Box. Vol. 31, no. 22. 27 December 1969. p. 117.

- ^ "Top 100 LP's". Record World. Vol. 24, no. 1176. 27 December 1969. p. 52.

- ^ "Dutch Single Charts > The Kinks". dutchcharts.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 16 August 2024.

References

[edit]Print articles

- Alterman, Loraine (18 December 1969). "Who Let the Kinks In?". Rolling Stone.

- Daly, Mike; Marcus, Greil (1 November 1969). "Arthur (Or The Decline and Fall of the British Empire)". Rolling Stone. No. 45. San Francisco: Straight Arrow Publishers, Inc. pp. 38–39. Archived from the original on 22 February 2010. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

Bibliography

- Davies, Ray (1995). X-Ray. New York: Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-611-9.

- Davies, Dave (1996). Kink. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 0-7868-8269-7.

- Hasted, Nick (2011). The Story of The Kinks: You Really Got Me. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84938-660-9.

- Hinman, Doug (2004). The Kinks: All Day and All of the Night. Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 0-87930-765-X.

- Kitts, Thomas (2007). Ray Davies: Not Like Everybody Else. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-97769-2.

- Marten, Neville; Hudson, Jeff (2007). The Kinks. London: Sanctuary Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86074-387-0.

- Miller, Andy (2003). The Kinks are the Village Green Preservation Society. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8264-1498-2.

- Rogan, Johnny (1998). The Complete Guide to the Music of The Kinks. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-6314-2.

- Savage, John (1984). The Kinks. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-13379-7.