Lebanon

Republic of Lebanon | |

|---|---|

Anthem:

| |

Location of Lebanon (in green) | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Beirut 33°54′N 35°32′E / 33.900°N 35.533°E |

| Official languages | Arabic[1] |

| Local vernacular | Lebanese Arabic[2] |

| Recognised minority language | French[a] |

| Ethnic groups (2021)[3] | |

| Demonym(s) | Lebanese |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic that includes confessionalism[4] |

| Vacant | |

| Najib Mikati | |

| Nabih Berri | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Establishment | |

| 1516 | |

| 1 December 1843 | |

| 9 June 1861 | |

| 1 September 1920 | |

| 23 May 1926 | |

• Independence declared | 22 November 1943 |

• French mandate ended | 24 October 1945 |

• Withdrawal of French forces | 17 April 1946 |

| 24 May 2000 | |

| 30 April 2005 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 10,452 km2 (4,036 sq mi) (161st) |

• Water (%) | 1.8 |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | 5,364,482[5] (117th) |

• Density | 513/km2 (1,328.7/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2011) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | high (109th) |

| Currency | Lebanese pound (LBP) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Drives on | Right[9] |

| Calling code | +961[10] |

| ISO 3166 code | LB |

| Internet TLD | |

33°50′N 35°50′E / 33.833°N 35.833°E Lebanon,[b] officially the Republic of Lebanon,[c] is a country in the Levant region of West Asia, bordered by Syria to the north and east, Israel to the south, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west; Cyprus lies a short distance from the country's coastline. It is at the crossroads of the Mediterranean Basin and the Arabian Peninsula.[11] Lebanon has a population of more than five million and an area of 10,452 square kilometres (4,036 sq mi). Beirut is the country's capital and largest city.

Human habitation in Lebanon dates to 5000 BC.[12] From 3200 to 539 BC, it was part of Phoenicia, a maritime empire that stretched the Mediterranean Basin.[13] In 64 BC, the region became part of the Roman Empire, and later the Byzantine Empire. After the 7th century, it came under the rule of different caliphates, including the Rashidun, Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphate. The 11th century saw the establishment of Crusader states, which fell to the Ayyubids and the Mamluks, and eventually the Ottomans. Under Ottoman ruler Abdulmejid I, the first Lebanese proto-state, the Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate, was established in the 19th century as a home for Maronite Christians, in the Tanzimat period.

After the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire following World War I, Lebanon came under the Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon, administered by France, which established Greater Lebanon. By 1943, Lebanon had gained independence from Free France and established a distinct form of confessionalist government, with the state's major religious groups being apportioned specific political powers. The new Lebanese state was relatively stable after independence,[14] but this was ultimately shattered by the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990). Lebanon was also subjugated by two military occupations: Syria from 1976 to 2005 and Israel from 1985 to 2000. Lebanon has been the scene of several conflicts with Israel, of which the ongoing war marks the fourth Israeli invasion of it since 1978.

Lebanon is a developing country, ranked 112th on the Human Development Index.[15] It has been classified as an upper-middle-income state.[16] The Lebanese liquidity crisis, coupled with nationwide corruption and disasters such as the 2020 Beirut explosion, precipitated the collapse of Lebanon's currency and fomented political instability, widespread resource shortages, and high unemployment and poverty. The World Bank has defined Lebanon's economic crisis as one of the world's worst since the 19th century.[17][18] Despite the country's small size,[19] Lebanese culture is renowned both in the Arab world and globally, powered primarily by the Lebanese diaspora.[20] Lebanon is a founding member of the United Nations and of the Arab League,[21] and is a member of the Non-Aligned Movement, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie, and the Group of 77.

Etymology

The name of Mount Lebanon originates from the Phoenician root lbn (𐤋𐤁𐤍) meaning "white", apparently from its snow-capped peaks.[22][23] Occurrences of the name have been found in different Middle Bronze Age texts from the library of Ebla,[24] and three of the twelve tablets of the Epic of Gilgamesh. The name is recorded in Egypt as rmnn (Ancient Egyptian: 𓂋𓏠𓈖𓈖𓈉; it had no letter corresponding to l).[25] The name occurs nearly 70 times in the Hebrew Bible as לְבָנוֹן Ləḇānon.[26]

Lebanon as the name of an administrative unit (as opposed to the mountain range) that was introduced with the Ottoman reforms of 1861 as the Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate (Arabic: متصرفية جبل لبنان; Turkish: Cebel-i Lübnan Mutasarrıflığı), continued in the name of Greater Lebanon (Arabic: دولة لبنان الكبير Dawlat Lubnān al-Kabīr; French: État du Grand Liban) in 1920, and eventually in the name of the sovereign Republic of Lebanon (Arabic: الجمهورية اللبنانية al-Jumhūriyyah al-Lubnāniyyah) upon its independence in 1943.[citation needed]

History

Antiquity

The Natufian culture was the first to become sedentary at around 12000 BC.[32]

Evidence of early settlement in Lebanon was found in Byblos, considered among the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world.[12] The evidence dates back to earlier than 5000 BC. Archaeologists discovered remnants of prehistoric huts with crushed limestone floors, primitive weapons, and burial jars left by the Neolithic and Chalcolithic fishing communities who lived on the shore of the Mediterranean Sea over 7,000 years ago.[33]

Lebanon was part of northern Canaan, and consequently became the homeland of Canaanite descendants, the Phoenicians, a seafaring people based in the coastal strip of the northern Levant who spread across the Mediterranean in the first millennium BC.[34] The most prominent Phoenician cities were Byblos, Sidon and Tyre. According to the Bible, King Hiram of Tyre collaborated closely with Solomon, supplying cedar logs for Solomon's Temple and sending skilled workers.[35] The Phoenicians are credited with the invention of the oldest verified alphabet, which subsequently inspired the Greek alphabet and the Latin one thereafter.[36]

In the 9th century BC, Phoenician colonies, including Carthage in present-day Tunisia and Cádiz in present-day Spain, flourished throughout the Mediterranean. Subsequently, foreign powers, starting with the Neo-Assyrian Empire, imposed tribute and attacked non-compliant cities. The Neo-Babylonian Empire took control in the 6th century BC.[35] In 539 BC, The cities of Phoenicia were then incorporated into the Achaemenid Empire by Cyrus the Great.[37] The Phoenician city-states were later incorporated into the empire of Alexander the Great following the siege of Tyre in 332 BCE.[37]

In 64 BC, the Roman general Pompey had the region of Syria annexed into the Roman Republic. The area was then split into two Imperial Provinces under the Roman Empire, Coele-Syria and Phoenice, the latter which the land of present-day Lebanon was a part of.

The region that is now Lebanon, as with the rest of Syria and much of Anatolia, became a major center of Christianity in the Roman Empire during the early spread of the faith. During the late 4th and early 5th century, a hermit named Maron established a monastic tradition focused on the importance of monotheism and asceticism near the Mediterranean mountain range known as Mount Lebanon. The monks who followed Maron spread his teachings among Lebanese in the region. These Christians became known as Maronites and moved into the mountains to avoid religious persecution by Roman authorities.[38] During the frequent Roman–Persian Wars that lasted for many centuries, the Sasanian Empire occupied what is now Lebanon from 619 till 629.[39]

Middle Ages

During the 7th century, Muslims conquered Syria from the Byzantines, incorporating the region, including modern-day Lebanon, under the Islamic Caliphate.[40] In the era of Uthman's caliphate (644–656), Islam gained significant influence in Damascus, led by Mu'awiya, a relative of Uthman, serving as the governor. Mu'awiya sent forces to the coastal region of Lebanon, prompting conversions to Islam among the coastal population. However, the mountainous areas retained their Christian or other cultural practices.[35] Despite Islam and Arabic becoming officially dominant, the population's conversion from Christianity and Syriac language was gradual. The Maronite community, in particular, managed to maintain a large degree of autonomy despite the succession of rulers over Lebanon and Syria. The relative isolation of the Lebanese mountains meant the mountains served as a refuge in the times of religious and political crises in the Levant. As such, the mountains displayed religious diversity and the existence of several well-established sects and religions, notably, Maronites, Druze, Shiite Muslims, Ismailis, Alawites and Jacobites.[41]

After the Islamic conquest, Mediterranean trade declined for three centuries due to conflicts with the Byzantines. The ports of Tyre, Sidon, Beirut, and Tripoli struggled to recover, sustaining small populations under Umayyad and Abbasid rule. Christians and Jews were often obligated to pay the jizya, or poll tax levied on non-Muslims.[40] During the 980s, the Fatimid Caliphate took control of the Levant, including Mount Lebanon, resulting in the rejuvenation of Mediterranean trade along the Lebanese coast through renewed connections with Byzantium and Italy. This resurgence saw Tripoli and Tyre flourishing well into the 11th century, focusing on exports such as textiles, sugar, and glassware.[40]

During the 11th century, the Druze religion emerged from a branch of Shia Islam. The new religion gained followers in the southern portion of Mount Lebanon. The southern portion of Mount Lebanon was ruled by Druze feudal families till the early 14th century. The Maronite population increased gradually in Northern Mount Lebanon and the Druze have remained in Southern Mount Lebanon until the modern era. Keserwan, Jabal Amel and the Beqaa Valley was ruled by Shia feudal families under the Mamluks and the Ottoman Empire. Major cities on the coast, Sidon, Tyre, Acre, Tripoli, Beirut, and others, were directly administered by the Muslim Caliphs and the people became more fully absorbed by the Arab culture.

Following the fall of Roman Anatolia to the Muslim Turks, the Byzantines put out a call to the Pope in Rome for assistance in the 11th century. The result was a series of wars known as the Crusades launched by the Franks from Western Europe to reclaim the former Byzantine Christian territories in the Eastern Mediterranean, especially Syria and Palestine (the Levant). The First Crusade succeeded in temporarily establishing the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the County of Tripoli as Roman Catholic Christian states along the coast.[42] These crusader states made a lasting impact on the region, though their control was limited, and the region returned to full Muslim control after two centuries following the conquest by the Mamluks.

Among the most lasting effects of the Crusades in this region was the contact between the Franks (i.e., the French) and the Maronites. Unlike most other Christian communities in the Eastern Mediterranean, who swore allegiance to Constantinople or other local patriarchs, the Maronites proclaimed allegiance to the Pope in Rome. As such the Franks saw them as Roman Catholic brethren. These initial contacts led to centuries of support for the Maronites from France and Italy, even after the fall of the Crusader states in the region.

Ottoman rule

In 1516, Lebanon became part of the Ottoman Empire, with governance administered indirectly through local emirs.[43] Lebanon's area was organized into provinces: Northern and Southern Mount Lebanon, Tripoli, Baalbek and Beqaa Valley, and Jabal Amil.

In 1590, Druze tribal leader Fakhr al-Din II succeeded Korkmaz in southern Mount Lebanon and quickly asserted his authority as the paramount emir of the Druze in the Shouf region. Eventually, he was appointed Sanjak-bey, overseeing various Ottoman sub-provinces and tax collection. Expanding his influence extensively, he even constructed a fort in Palmyra.[44] However, this expansion raised concerns for Ottoman Sultan Murad IV, leading to a punitive expedition in 1633. Fakhr al-Din II was captured, imprisoned for two years, and subsequently executed in April 1635, along with one of his sons.[45] Surviving members of his family continued to govern a reduced area under closer Ottoman supervision until the late 17th century. On the death of the last Maan emir, various members of the Shihab clan ruled Mount Lebanon until 1830.

While the history of Druze-Christian relations in Lebanon has generally been marked by harmony and peaceful coexistence,[46][47][48][49] there were occasional periods of tension, notably during the 1860 Mount Lebanon civil war, during which around 10,000 Christians were killed by the Druze.[50] Shortly afterwards, the Emirate of Mount Lebanon, which lasted about 400 years, was replaced by the Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate, as a result of a European-Ottoman treaty called the Règlement Organique. The Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate[51][52][53] (1861–1918, Arabic: متصرفية جبل لبنان; Turkish: Cebel-i Lübnan Mutasarrıflığı) was one of the Ottoman Empire's subdivisions following the Tanzimat reform. After 1861 there existed an autonomous Mount Lebanon with a Christian mutasarrıf, which had been created as a homeland for the Maronites under European diplomatic pressure following the 1860 massacres. The Maronite Catholics and the Druze founded modern Lebanon in the early eighteenth century, through the ruling and social system known as the "Maronite-Druze dualism" in Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate.[54]

The Baalbek and Beqaa Valley and Jabal Amel was ruled intermittently by various Shia feudal families, especially the Al Ali Alsagheer in Jabal Amel that remained in power until 1865 when Ottomans took direct ruling of the region. Youssef Bey Karam,[58] a Lebanese nationalist played an influential role in Lebanon's independence during this era.

Lebanon experienced profound devastation in the First World War when the Ottoman army assumed direct control, disrupting supplies and confiscating animals, ultimately leading to a severe famine.[43] During the war, approximately 100,000 people in Beirut and Mount Lebanon died due to starvation.[59]

French Mandate

Amidst the height of the First World War, the Sykes–Picot Agreement of 1916, a secret pact between Britain and France, delineated Lebanon and its surrounding areas as regions open to potential French influence or control.[43] After the Allies emerged victorious in the war, the Ottoman Empire ultimately collapsed, losing control over the area. Soon after the war, Patriarch Elias Peter Hoayek, representing the Maronite Christians, successfully campaigned for an expanded territory at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, also including areas with significant Muslim and Druze populations in addition to the Christian-dominated Mount Lebanon.[43]

In 1920, King Faisal I proclaimed the Arab Kingdom of Syria's independence and asserted control over Lebanon. However, following a defeat to the French at the Battle of Maysalun, the kingdom was dissolved.[43] Around the same time, at the San Remo Conference, tasked with deciding the fate of former Ottoman territories, it was determined that Syria and Lebanon would fall under French rule; Shortly afterward, the formal division of territories took place in the Treaty of Sèvres, signed a few months later.[43]

On 1 September 1920, Greater Lebanon, or Grand Liban, was officially established under French control as a League of Nations Mandate, following the terms outlined in the proposed Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon. Greater Lebanon united the regions of Mount Lebanon, North Lebanon, South Lebanon, and the Bekaa, with Beirut as its designated capital.[60][43] These specified boundaries later evolved into the present-day configuration of Lebanon. This arrangement was later ratified in July 1922.[43] The Lebanese Republic was officially proclaimed on 1 September 1926, with the adoption of a constitution inspired by the French constitution on 23 May of the same year. While a Lebanese government was established, the country continued to be under French control.[43]

Pressure on German-occupied France

Lebanon gained a measure of independence while France was occupied by Germany.[61] General Henri Dentz, the Vichy High commissioner for Syria and Lebanon, played a major role in the independence of the nation. The Vichy authorities in 1941 allowed Germany to move aircraft and supplies through Syria to Iraq where they were used against British forces. The United Kingdom, fearing that Nazi Germany would gain full control of Lebanon and Syria by pressure on the weak Vichy government, sent its army into Syria and Lebanon.[62]

After the fighting ended in Lebanon, General Charles de Gaulle visited the area. Under political pressure from both inside and outside Lebanon, de Gaulle recognized the independence of Lebanon. On 26 November 1941, General Georges Catroux announced that Lebanon would become independent under the authority of the Free French government. Elections were held in 1943 and on 8 November 1943 the new Lebanese government unilaterally abolished the mandate. The French reacted by imprisoning the new government. Lebanese nationalists declared a provisional government, and the British diplomatically intervened on their behalf. In the face of intense British pressure and protests by Lebanese nationalists, the French reluctantly released the government officials on 22 November 1943, and accepted the independence of Lebanon.[63]

Independence from Free France

Following the end of World War II in Europe the French mandate may be said to have been terminated without any formal action on the part of the League of Nations or its successor the United Nations. The mandate was ended by the declaration of the mandatory power, and of the new states themselves, of their independence, followed by a process of piecemeal unconditional recognition by other powers, culminating in formal admission to the United Nations. Article 78 of the UN Charter ended the status of tutelage for any member state: "The trusteeship system shall not apply to territories which have become Members of the United Nations, relationship among which shall be based on respect for the principle of sovereign equality."[64] So when the UN officially came into existence on 24 October 1945, after ratification of the United Nations Charter by the five permanent members, as both Syria and Lebanon were founding member states, the French mandate for both was legally terminated on that date and full independence attained.[65] The last French troops withdrew in December 1946.

Lebanon's unwritten National Pact of 1943 required that its president be Maronite Christian, its speaker of the parliament to be a Shia Muslim, its prime minister be Sunni Muslim, and the Deputy Speaker of Parliament and the Deputy Prime Minister be Greek Orthodox.[66]

Lebanon's history since independence has been marked by alternating periods of political stability and turmoil interspersed with prosperity built on Beirut's position as a regional center for finance and trade.[67]

In May 1948, Lebanon supported neighboring Arab countries in a war against Israel. While some irregular forces crossed the border and carried out minor skirmishes against Israel, it was without the support of the Lebanese government, and Lebanese troops did not officially invade.[68] Lebanon agreed to support the forces with covering artillery fire, armored cars, volunteers and logistical support.[69] On 5–6 June 1948, the Lebanese army – led by the then Minister of National Defense, Emir Majid Arslan – captured Al-Malkiyya. This was Lebanon's only success in the war.[70]

100,000 Palestinians fled to Lebanon because of the war. Israel did not permit their return after the cease-fire.[71] As of 2017, between 174,000 and 450,000 Palestinian refugees live in Lebanon with about half in refugee camps (although these are often decades old and resemble neighborhoods).[72] Often Palestinians are legally barred from owning property or performing certain occupations.[73] According to Human Rights Watch, Palestinian refugees in Lebanon live in "appalling social and economic conditions."

In 1958, during the last months of President Camille Chamoun's term, an insurrection broke out, instigated by Lebanese Muslims who wanted to make Lebanon a member of the United Arab Republic. Chamoun requested assistance, and 5,000 United States Marines were briefly dispatched to Beirut on 15 July. After the crisis, a new government was formed, led by the popular former general Fouad Chehab.

Until the early 1970s, Lebanon was dubbed "the Switzerland of the Middle East" for its unique status as both a snow-capped holiday destination and secure banking hub for Gulf Arabs.[74] Beirut was also nicknamed "the Paris of the Middle East."[75]

Civil War and occupation

With the 1970 defeat of the PLO in Jordan, many Palestinian militants relocated to Lebanon, increasing their armed campaign against Israel. The relocation of Palestinian bases also led to increasing sectarian tensions between Palestinians versus the Maronites and other Lebanese factions.

In 1975, following increasing sectarian tensions, largely boosted by Palestinian militant relocation into South Lebanon, a full-scale civil war broke out in Lebanon. The Lebanese Civil War pitted a coalition of Christian groups against the joint forces of the PLO, left-wing Druze and Muslim militias. In June 1976, Lebanese President Élias Sarkis asked for the Syrian Army to intervene on the side of the Christians and help restore peace.[76] In October 1976 the Arab League agreed to establish a predominantly Syrian Arab Deterrent Force, which was charged with restoring calm.[77] PLO attacks from Lebanon into Israel in 1977 and 1978 escalated tensions between the countries. On 11 March 1978, 11 Fatah fighters landed on a beach in northern Israel and hijacked two buses full of passengers on the Haifa – Tel-Aviv road, shooting at passing vehicles in what became known as the Coastal Road massacre. They killed 37 and wounded 76 Israelis before being killed in a firefight with Israeli forces.[78] Israel invaded Lebanon four days later in Operation Litani. The Israeli Army occupied most of the area south of the Litani River. The UN Security Council passed Resolution 425 calling for immediate Israeli withdrawal and creating the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL), charged with attempting to establish peace.

Israeli forces withdrew later in 1978, but retained control of the southern region by managing a 19-kilometre-wide (12 mi) security zone along the border. These positions were held by the South Lebanon Army (SLA), a Christian militia under the leadership of Major Saad Haddad backed by Israel. The Israeli Prime Minister, Likud's Menachem Begin, compared the plight of the Christian minority in southern Lebanon (then about 5% of the population in SLA territory) to that of European Jews during World War II.[79] The PLO routinely attacked Israel during the period of the cease-fire, with over 270 documented attacks.[80] People in Galilee regularly had to leave their homes during these shellings. Documents captured in PLO headquarters after the invasion showed they had come from Lebanon.[81] PLO leader Yasser Arafat refused to condemn these attacks on the grounds that the cease-fire was only relevant to Lebanon.[82]

In April 1980 the killing of two UNIFIL soldiers and the injuring of a third by the South Lebanon Army, near At Tiri, in the buffer zone led to the At Tiri incident. On 17 July 1981, Israeli aircraft bombed multi-story apartment buildings in Beirut that contained offices of PLO associated groups. The Lebanese delegate to the United Nations Security Council claimed that 300 civilians had been killed and 800 wounded. The bombing led to worldwide condemnation, and a temporary embargo on the export of U.S. aircraft to Israel.[83] In August 1981, defense minister Ariel Sharon began to draw up plans to attack PLO military infrastructure in West Beirut, where PLO headquarters and command bunkers were located.[84]

In 1982, PLO attacks from Lebanon on Israel led to an Israeli invasion, aiming to support Lebanese forces in driving out the PLO. A multinational force of American, French and Italian contingents (joined in 1983 by a British contingent) were deployed in Beirut after the Israeli siege of the city, to supervise the evacuation of the PLO. The civil war re-emerged in September 1982 after the assassination of Lebanese President Bachir Gemayel, an Israeli ally, and subsequent fighting. During this time a number of sectarian massacres occurred, such as in Sabra and Shatila, and in several refugee camps.[85] The multinational force was withdrawn in the spring of 1984, following a devastating bombing attack during the previous year.

During the early 1980s, Hezbollah, a Shiite Islamist militant group and political party, came into existence through the efforts of Shiite clerics who were financially supported and trained by Iran. Arising in the aftermath of the 1982 war and drawing inspiration from the Islamic Revolution in Iran, Hezbollah actively engaged in combat against Israel as well as suicide attacks, car bombings and assassinations. Their objectives encompassed eliminating Israel, fighting for the Shia cause in the Lebanese civil war, ending Western presence in Lebanon, and establishing a Shiite Khomeinist Islamic state.[86][40][87]

In the late 1980s, as Amine Gemayel’s second term as president drew to an end, the Lebanese pound collapsed. At the end of 1987 US$1 was worth £L500. This meant the legal minimum wage was worth just $17 a month. Most goods in shops were priced in dollars. A Save the Children director estimated that 200,000–300,000 children were need of assistance and were living almost entirely on bread, which was subsidized by the government. Those who could relied on foreign assistance. Hezbollah was receiving about $3–5 million a month from Iran.[88] In September 1988, the Parliament failed to elect a successor to President Gemayel as a result of differences between the Christians, Muslims, and Syrians. The Arab League Summit of May 1989 led to the formation of a Saudi–Moroccan–Algerian committee to solve the crisis. On 16 September 1989 the committee issued a peace plan which was accepted by all. A ceasefire was established, the ports and airports were re-opened and refugees began to return.[77]

In the same month, the Lebanese Parliament agreed to the Taif Agreement, which included an outline timetable for Syrian withdrawal from Lebanon and a formula for the de-confessionalization of the Lebanese political system.[77] The civil war ended at the end of 1990 after 16 years; it had caused massive loss of human life and property and devastated the country's economy. It is estimated that 150,000 people were killed and another 200,000 wounded.[89] Nearly a million civilians were displaced by the war, and some never returned.[90] Parts of Lebanon were left in ruins.[91] The Taif Agreement has still not been implemented in full and Lebanon's political system continues to be divided along sectarian lines. Conflict between Israel and Lebanese militants continued, leading to a series of violent events and clashes including the Qana massacre.[92][93][94][95] In May 2000, Israeli forces fully withdrew from Lebanon.[96][93][97] Since then, 25 May is regarded by the Lebanese as the Liberation Day.[98][99][93] The internal political situation in Lebanon significantly changed in the early 2000s. After the Israeli withdrawal from southern Lebanon and the death of former president Hafez al-Assad in 2000, the Syrian military presence faced criticism and resistance from the Lebanese population.[100]

On 14 February 2005, former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri was assassinated in a car bomb explosion.[101] Leaders of the March 14 Alliance accused Syria of the attack,[102] while Syria and the March 8 Alliance claimed that Israel was behind the assassination. The Hariri assassination marked the beginning of a series of assassinations that resulted in the death of many prominent Lebanese figures.[nb 1] The assassination triggered the Cedar Revolution, a series of demonstrations which demanded the withdrawal of Syrian troops from Lebanon and the establishment of an international commission to investigate the assassination. Under pressure from the West, Syria began withdrawing,[103] and by 26 April 2005 all Syrian soldiers had returned to Syria.[104]

UNSC Resolution 1595 called for an investigation into the assassination.[105] The United Nations International Independent Investigation Commission published preliminary findings on 20 October 2005 in the Mehlis report, which cited indications that the assassination was organized by Syrian and Lebanese intelligence services.[106][107][108][109]

Post-war revolution and spillover of the Syrian conflict

On 12 July 2006, Hezbollah launched a series of rocket attacks and raids into Israeli territory, where they killed three Israeli soldiers and captured two others.[110] Israel responded with airstrikes and artillery fire on targets in Lebanon, and a ground invasion of southern Lebanon, resulting in the 2006 Lebanon War. The conflict was officially ended by the UNSC Resolution 1701 on 14 August 2006, which ordered a ceasefire, the withdrawal of Israeli forces from Lebanon, and the disarmament of Hezbollah.[111][112] Some 1,191 Lebanese[113] and 160 Israelis[114] were killed in the conflict. Beirut's southern suburb was heavily damaged by Israeli airstrikes.[115]

In 2007, the Nahr al-Bared refugee camp became the center of the 2007 Lebanon conflict between the Lebanese Army and Fatah al-Islam. At least 169 soldiers, 287 insurgents and 47 civilians were killed in the battle. Funds for the reconstruction of the area have been slow to materialize.[116] Between 2006 and 2008, a series of protests led by groups opposed to the pro-Western Prime Minister Fouad Siniora demanded the creation of a national unity government, over which the mostly Shia opposition groups would have veto power. When Émile Lahoud's presidential term ended in October 2007, the opposition refused to vote for a successor unless a power-sharing deal was reached, leaving Lebanon without a president.

On 9 May 2008, Hezbollah and Amal forces, sparked by a government declaration that Hezbollah's communications network was illegal, seized western Beirut,[117][118] the most important Sunni center in Lebanon, leading to an intrastate military conflict.[119] The Lebanese government denounced the violence as a coup attempt.[120] At least 62 people died in the resulting clashes between pro-government and opposition militias.[121] On 21 May 2008, the signing of the Doha Agreement ended the fighting.[117][121] As part of the accord, which ended 18 months of political paralysis,[122] Michel Suleiman became president and a national unity government was established, granting a veto to the opposition.[117] The agreement was a victory for opposition forces, as the government caved in to all their main demands.[121]

In early January 2011, the national unity government collapsed due to growing tensions stemming from the Special Tribunal for Lebanon, which was expected to indict Hezbollah members for the Hariri assassination.[123] The parliament elected Najib Mikati, the candidate for the Hezbollah-led March 8 Alliance, Prime Minister of Lebanon, making him responsible for forming a new government.[124] Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah later accused Israel of assassinating Hariri.[125] A report leaked by the Al-Akhbar newspaper in November 2010 stated that Hezbollah had drafted plans for a violent takeover of the country in case the Special Tribunal for Lebanon issued an indictment against its members.[126]

In 2012, the Syrian civil war threatened to spill over in Lebanon, causing incidents of sectarian violence and armed clashes between Sunnis and Alawites in Tripoli.[127] According to UNHCR, the number of Syrian refugees in Lebanon increased from around 250,000 in early 2013 to 1,000,000 in late 2014.[128] In 2013, The Lebanese Forces Party, the Kataeb Party and the Free Patriotic Movement voiced concerns that the country's sectarian based political system is being undermined by the influx of Syrian refugees.[129] On 6 May 2015, UNHCR suspended registration of Syrian refugees at the request of the Lebanese government.[130] In February 2016, the Lebanese government signed the Lebanon Compact, granting a minimum of €400 million of support for refugees and vulnerable Lebanese citizens.[131] As of October 2016, the government estimated that the country hosts 1.5 million Syrians.[132]

National crisis (2019–present)

On 17 October 2019, the first of a series of mass civil demonstrations erupted;[133][134][135] they were initially triggered by planned taxes on gasoline, tobacco and online phone calls such as through WhatsApp,[136][137][138] but quickly expanded into a country-wide condemnation of sectarian rule,[139] a stagnant economy and liquidity crisis, unemployment, endemic corruption in the public sector,[139] legislation (such as banking secrecy) that is perceived to shield the ruling class from accountability[140][141] and failures from the government to provide basic services such as electricity, water and sanitation.[142]

As a result of the protests, Lebanon entered a political crisis, with Prime Minister Saad Hariri tendering his resignation and echoing protestors' demands for a government of independent specialists.[143] Other politicians targeted by the protests have remained in power. On 19 December 2019, former Minister of Education Hassan Diab was designated the next prime minister and tasked with forming a new cabinet.[144] Protests and acts of civil disobedience have since continued, with protesters denouncing and condemning the designation of Diab as prime minister.[145][146][147] Lebanon is suffering the worst economic crisis in decades.[148][149] Lebanon is the first country in the Middle East and North Africa to see its inflation rate exceed 50% for 30 consecutive days, according to Steve H. Hanke, professor of applied economics at the Johns Hopkins University.[150] On 4 August 2020, an explosion at the port of Beirut, Lebanon's main port, destroyed the surrounding areas, killing over 200 people, and injuring thousands more. The cause of the explosion was later determined to be 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate that had been unsafely stored, and accidentally set on fire that Tuesday afternoon.[151] Protests resumed within days following the explosion, which resulted in the resignation of Prime Minister Hassan Diab and his cabinet on 10 August 2020, nonetheless continuing to stay in office in a caretaker capacity.[152] Demonstrations continued into 2021 with Lebanese blocking the roads with burned tires protesting against the poverty and the economic crisis.

On 11 March 2021 the caretaker minister of energy Raymond Ghajar warned that Lebanon was threatened with "total darkness" at the end of March if no money was secured to buy fuel for power stations.[153] In August 2021, a large fuel explosion in northern Lebanon killed 28 people.[154] September saw the formation of a new cabinet led by former prime minister Najib Mikati.[155] On 9 October 2021, the entire nation lost power for 24 hours after its two main power stations ran out of power due to the currency and fuel shortage.[156] Days later, sectarian violence in Beirut killed a number of people in the deadliest clashes in the country since 2008.[157] By January 2022, BBC News reported that the crisis in Lebanon had deepened further, with the value of the Lebanese pound plummeting and a scheduled general election expected to be delayed indefinitely.[158] The postponement of parliamentary elections was said to prolong the political deadlock in the country. The European Parliament called Lebanon's present situation a 'man-made disaster caused by a handful of men across the political class'.[159]

In May 2022, Lebanon held its first election since a painful economic crisis dragged it to the brink of becoming a failed state. Lebanon's crisis has been so severe that more than 80 percent of the population is now considered poor by the United Nations.[160] In the election the Shia Muslim Hezbollah movement (and its allies) lost their parliamentary majority. Hezbollah did not lose any of its seats, but its allies lost seats. Hezbollah's ally, President Michel Aoun's Free Patriotic Movement, was no longer the biggest Christian party after the election. A rival Christian party, the Lebanese Forces led by Samir Geagea, became the largest Christian-based party in parliament. The Sunni Future Movement, led by former prime minister Saad Hariri, did not participate the election, leaving a political vacuum to other Sunni politicians to fill.[161][162][163] The Lebanese crisis became so severe that multiple boats left the coast holding migrants in a desperate run from the country. Many proved unsuccessful and fatal. In April 2022, 6 people died and around 50 people are rescued after an overloaded boat sunk in Tripoli.[164] And on 22 September, at least 94 people were killed when a boat carrying migrants from Lebanon capsized off Syria's coast. 9 people survived. Many were declared missing and some were found either dead or injured. Dead bodies were sent to nearby hospitals. 40 people are still missing as of 24 September.[165] On 1 February 2023, the central bank of Lebanon devalued the Lebanese pound by 90% amid the ongoing financial crisis.[166] This was the first time Lebanon had devalued its official exchange rate in 25 years.[167] As of 2023, Lebanon is considered to have become a failed state, suffering from chronic poverty, economic mismanagement and a banking collapse.[168]

The Israel–Hamas war sparked a renewed Israel–Hezbollah conflict.[169] Hezbollah has said it will not stop attacking Israel until Israel ceases its attacks in Gaza.[170] Starting with the Israeli explosion of Lebanese pagers and walkie talkies in September 2024,[171] the conflict escalated severely,[172] with the 23 September 2024 Israeli airstrikes on Lebanon killing at least 558 people,[173] and sparking a mass exodus from southern Lebanon.[174] On 27 September 2024, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah was killed in an Israeli airstrike.[175] On 1 October 2024, Lebanon was invaded by Israel with the objective of destroying infrastructure belonging to Hezbollah in the south of the country.[176]

Geography

Lebanon is located in West Asia between latitudes 33° and 35° N and longitudes 35° and 37° E. Its land straddles the "northwest of the Arabian Plate".[177] The country's surface area is 10,452 square kilometres (4,036 sq mi) of which 10,230 square kilometres (3,950 sq mi) is land. Lebanon has a coastline and border of 225 kilometres (140 mi) on the Mediterranean Sea to the west, a 375 kilometres (233 mi) border shared with Syria to the north and east and a 79 kilometres (49 mi) long border with Israel to the south.[178] The border with the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights is disputed by Lebanon in a small area called Shebaa Farms.[179]

Lebanon is divided into four distinct physiographic regions: the coastal plain, the Lebanon mountain range, the Beqaa Valley and the Anti-Lebanon Mountains. The narrow and discontinuous coastal plain stretches from the Syrian border in the north where it widens to form the Akkar plain to Ras al-Naqoura at the border with Israel in the south. The fertile coastal plain is formed of marine sediments and river deposited alluvium alternating with sandy bays and rocky beaches. Lebanon's mountains rise steeply parallel to the Mediterranean coast and form a ridge of limestone and sandstone that runs for most of the country's length.

The mountain range varies in width between 10 km (6 mi) and 56 km (35 mi); it is carved by narrow and deep gorges. The Lebanon mountains peak at 3,088 metres (10,131 ft) above sea level in Qurnat as Sawda' in North Lebanon and gradually slope to the south before rising again to a height of 2,695 metres (8,842 ft) in Mount Sannine. The Beqaa valley sits between the Lebanon mountains in the west and the Anti-Lebanon range in the east; it is a part of the Great Rift Valley system. The valley is 180 km (112 mi) long and 10 to 26 km (6 to 16 mi) wide, its fertile soil is formed by alluvial deposits. The Anti-Lebanon range runs parallel to the Lebanon mountains, its highest peak is in Mount Hermon at 2,814 metres (9,232 ft).[178]

The mountains of Lebanon are drained by seasonal torrents and rivers foremost of which is the 145 kilometres (90 mi) long Leontes that rises in the Beqaa Valley to the west of Baalbek and empties into the Mediterranean Sea north of Tyre.[178] Lebanon has 16 rivers all of which are non-navigable; 13 rivers originate from Mount Lebanon and run through the steep gorges and into the Mediterranean Sea, the other three arise in the Beqaa Valley.[180]

Climate

Lebanon has a moderate Mediterranean climate. In coastal areas, winters are generally cool and rainy whilst summers are hot and humid. In more elevated areas, temperatures usually drop below freezing during the winter with heavy snow cover that remains until early summer on the higher mountaintops.[178][181] Although most of Lebanon receives a relatively large amount of rainfall, when measured annually in comparison to its arid surroundings, certain areas in north-eastern Lebanon receives only little because of the rain shadow created by the high peaks of the western mountain range.[182]

Environment

In ancient times, Lebanon was covered by large forests of cedar trees, the national emblem of the country.[183] Millennia of deforestation have altered the hydrology in Mount Lebanon and changed the regional climate adversely.[184] As of 2012, forests covered 13.4% of the Lebanese land area;[185] they are under constant threat from wildfires caused by the long dry summer season.[186]

As a result of longstanding exploitation, few old cedar trees remain in pockets of forests in Lebanon, but there is an active program to conserve and regenerate the forests. The Lebanese approach has emphasized natural regeneration over planting by creating the right conditions for germination and growth. The Lebanese state has created several nature reserves that contain cedars, including the Shouf Biosphere Reserve, the Jaj Cedar Reserve, the Tannourine Reserve, the Ammouaa and Karm Shbat Reserves in the Akkar district, and the Forest of the Cedars of God near Bsharri.[187][188][189] Lebanon had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 3.76/10, ranking it 141st globally out of 172 countries.[190]

In 2010, the Environment Ministry set a 10-year plan to increase the national forest coverage by 20%, which is equivalent to the planting of two million new trees each year.[191] The plan, which was funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and implemented by the U.S. Forest Service (USFS), through the Lebanon Reforestation Initiative (LRI), was inaugurated in 2011 by planting cedar, pine, wild almond, juniper, fir, oak and other seedlings, in ten regions around Lebanon.[191] As of 2016, forests covered 13.6% of Lebanon, and other wooded lands represented a further 11%.[192] Since 2011, over 600,000 trees, including cedars and other native species, have been planted throughout the country as part of the Lebanon Reforestation Initiative (LRI).[193]

Lebanon contains two terrestrial ecoregions: Eastern Mediterranean conifer–sclerophyllous–broadleaf forests and Southern Anatolian montane conifer and deciduous forests.[194]

Beirut and Mount Lebanon have been facing a severe garbage crisis. After the closure of the Bourj Hammoud dump in 1997, the al-Naameh dumpsite was opened by the government in 1998. The al-Naameh dumpsite was planned to contain 2 million tons of waste for a limited period of six years at the most. It was designed to be a temporary solution, while the government would have devised a long-term plan. Sixteen years later al-Naameh was still open and exceeded its capacity by 13 million tons. In July 2015 the residents of the area, already protesting in the recent years, forced the closure of the dumpsite. The inefficiency of the government, as well as the corruption inside of the waste management company Sukleen in charge of managing the garbage in Lebanon, have resulted in piles of garbage blocking streets in Mount Lebanon and Beirut.[195]

In December 2015, the Lebanese government signed an agreement with Chinook Industrial Mining, part owned by Chinook Sciences, to export over 100,000 tons of untreated waste from Beirut and the surrounding area. The waste had accumulated in temporary locations following the government closure of the county's largest land fill site five months earlier. The contract was jointly signed with Howa International which has offices in the Netherlands and Germany. The contract is reported to cost $212 per ton. The waste, which is compacted and infectious, would have to be sorted and was estimated to be enough to fill 2,000 containers.[196] Initial reports that the waste was to be exported to Sierra Leone have been denied by diplomats.[197]

In February 2016, the government withdrew from negotiations after it was revealed that documents relating to the export of the trash to Russia were forgeries.[198] On 19 March 2016, the Cabinet reopened the Naameh landfill for 60 days in line with a plan it passed few days earlier to end the trash crisis. The plan also stipulates the establishment of landfills in Bourj Hammoud and Costa Brava, east and south of Beirut respectively. Sukleen trucks began removing piled garbage from Karantina and heading to Naameh. Environment Minister Mohammad Machnouk announced during a chat with activists that over 8,000 tons of garbage had been collected up to that point in only 24 hours as part of the government's trash plan. The plan's execution was ongoing at last report.[199] In 2017, Human Rights Watch found that Lebanon's garbage crisis, and open burning of waste in particular, was posing a health risk to residents and violating the state's obligations under international law.[200]

In September 2018, Lebanon's parliament passed a law that banned open dumping and burning of waste. Despite penalties set in case of violations, Lebanese municipalities have been openly burning the waste, putting the lives of people in danger. In October 2018, Human Rights Watch researchers witnessed the open burning of dumps in al-Qantara and Qabrikha.[201] On Sunday 13 October 2019 at night, a series of about 100 forest fires according to Lebanese Civil Defense, broke out and spread over large areas of Lebanon's forests. Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Al-Hariri confirmed his contact with a number of countries to send assistance via helicopters and firefighting planes,[202] Cyprus, Jordan, Turkey and Greece participated in firefighting. According to press reports on Tuesday (15 October), fire has decreased in different places due to the rains.[203] Lebanon's ongoing economic crisis has precipitated electricity shortages, prompting an increased reliance on diesel generators and subsequently contributing to environmental deterioration and health hazards. The scarcity of power has led to a heightened contamination of water sources. The compromised infrastructure, marked by sewage infiltrating drinking water, has given rise to significant health concerns, including an increase in cases of Hepatitis A. The health service, grappling with workforce shortages due to emigration, struggles amid a growing public health crisis.[204]

Government and politics

Lebanon is a parliamentary democracy that includes confessionalism.[205] The National Pact, erected in 1943, laid out a governing arrangement intended to harmonize the interests of the country's major religious groups.[206] The President has to be a Maronite Christian, the Prime Minister a Sunni Muslim, the Speaker of the Parliament a Shi’a Muslim, the Deputy Prime Minister and the Deputy Speaker of Parliament Eastern Orthodox.[207][208] This system is intended to deter sectarian conflict and to represent fairly the demographic distribution of the 18 recognized religious groups in government.[209][210]

Until 1975, Freedom House considered Lebanon to be among only two (together with Israel) politically free countries in the Middle East and North Africa region.[211] The country lost this status with the outbreak of the Civil War, and has not regained it since. Lebanon was rated "Partly Free" in 2013. Even so, Freedom House still ranks Lebanon as among the most democratic nations in the Arab world.[211] According to the V-Dem Democracy indices Lebanon is 2023 the second most electoral democratic country in the Middle East.[212]

Until 2005, Palestinians were forbidden to work in over 70 jobs because they did not have Lebanese citizenship. After liberalization laws were passed in 2007, the number of banned jobs dropped to around 20.[71] In 2010, Palestinians were granted the same rights to work as other foreigners in the country.[213] Lebanon's national legislature is the unicameral Parliament of Lebanon. Its 128 seats are divided equally between Christians and Muslims, proportionately between the 18 different denominations and proportionately between its 26 regions.[214] Prior to 1990, the ratio stood at 6:5 in favor of Christians, but the Taif Agreement, which put an end to the 1975–1990 civil war, adjusted the ratio to grant equal representation to followers of the two religions.[207]

The Parliament is elected for a four-year term by popular vote on the basis of sectarian proportional representation.[10] The executive branch consists of the President, the head of state, and the Prime Minister, the head of government. The parliament elects the president for a non-renewable six-year term by a two-thirds majority. The president appoints the Prime Minister,[215] following consultations with the parliament. The president and the prime minister form a cabinet, which must also adhere to the sectarian distribution set out by confessionalism.

In an unprecedented move, the Lebanese parliament has extended its own term twice amid protests, the last being on 5 November 2014,[216] an act which comes in direct contradiction with democracy and article #42 of the Lebanese constitution as no elections have taken place.[4] Lebanon was without a President between May 2014 and October 2016.[217][218] Nationwide elections were finally scheduled for May 2018.[219] As of August 2019, the Lebanese cabinet included two ministers directly affiliated with Hezbollah, in addition to a close but officially non-member minister.[220] The most recent parliamentary elections were held on 15 May 2022.[221]

Administrative divisions

Lebanon is divided into nine governorates (muḥāfaẓāt, Arabic: محافظات; singular muḥāfaẓah, Arabic: محافظة) which are further subdivided into twenty-five districts (aqdyah, Arabic: أقضية; singular: qadāʾ Arabic: قضاء).[222] The districts themselves are also divided into several municipalities, each enclosing a group of cities or villages. The governorates and their respective districts are listed below:

- Beirut Governorate

- Beirut Governorate comprises the city of Beirut and is not divided into districts.

- Akkar Governorate

- Baalbek-Hermel Governorate

- Beqaa Governorate

- Rashaya

- Western Beqaa (al-Beqaa al-Gharbi)

- Zahle

- Keserwan-Jbeil Governorate

- Mount Lebanon Governorate (Jabal Lubnan/Jabal Lebnen)

- Nabatieh Governorate (Jabal Amel)

- North Governorate (ash-Shamal/shmel)

- South Governorate (al-Janoub/Jnub)

Foreign relations

Lebanon concluded negotiations on an association agreement with the European Union in late 2001, and both sides initialed the accord in January 2002. It is included in the European Union's European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), which aims at bringing the EU and its neighbours closer. Lebanon also has bilateral trade agreements with several Arab states and is working toward accession to the World Trade Organization.

Lebanon enjoys good relations with virtually all of the other Arab countries (despite historic tensions with Libya and Syria), and hosted an Arab League Summit in March 2002 for the first time in over 35 years. Lebanon is a member of the Francophonie countries and hosted the Francophonie Summit in October 2002 as well as the Jeux de la Francophonie in 2009.

Military

The Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) has 72,000 active personnel,[223] including 1,100 in the air force, and 1,000 in the navy.[224] The LAF is considered less powerful and influential than Hezbollah in Lebanon. Hezbollah has 20,000 active fighters and 20,000 in reserves and is supplied with advanced weaponry, including rockets and drones from Iran.[225][226]

The Lebanese Armed Forces' primary missions include defending Lebanon and its citizens against external aggression, maintaining internal stability and security, confronting threats against the country's vital interests, engaging in social development activities, and undertaking relief operations in coordination with public and humanitarian institutions.[227]

Lebanon is a major recipient of foreign military aid.[228] With over $400 million since 2005, it is the second largest per capita recipient of American military aid behind Israel.[229]

Hezbollah effectively controls large portions of southern Lebanon, and has greater military strength than the Lebanese armed forces.[230] The government of Lebanon has been unable or unwilling to prevent Hezbollah attacks on Israel, and violent conflict between Israel and Hezbollah in southern Lebanon.[231] Many Islamist and Palestinian militias operate in refugee camps because of an agreement that prevents the Lebanese Army from entering them. Many people wanted by the Lebanese government are believed to have taken refuge in the camp as a result of the lack of Lebanese authority.

Law

There are 18 officially recognized religious groups in Lebanon, each with its own family law legislation and set of religious courts.[232] The Lebanese legal system is based on the French system, and is a civil law country, with the exception for matters related to personal status (succession, marriage, divorce, adoption, etc.), which are governed by a separate set of laws designed for each sectarian community. For instance, the Islamic personal status laws are inspired by the Sharia law.[233] For Muslims, these tribunals deal with questions of marriage, divorce, custody, and inheritance and wills. For non-Muslims, personal status jurisdiction is split: the law of inheritance and wills falls under national civil jurisdiction, while Christian and Jewish religious courts are competent for marriage, divorce, and custody. Catholics can additionally appeal before the Vatican Rota court.[234]

The most notable set of codified laws is the Code des Obligations et des Contrats promulgated in 1932 and equivalent to the French Civil Code.[233] Capital punishment is still de facto used to sanction certain crimes, but no longer enforced.[clarification needed][233] The Lebanese court system consists of three levels: courts of first instance, courts of appeal, and the court of cassation. The Constitutional Council rules on constitutionality of laws and electoral frauds. There also is a system of religious courts having jurisdiction over personal status matters within their own communities, with rules on matters such as marriage and inheritance.[235]

In 1990, article 95 was amended to provide that the parliament shall take necessary measures to abolish political structure based on religious affiliation, but that until such time only the highest positions in public civil service, including the judiciary, military, security forces, public and mixed institutions, shall be divided equally between Christians and Muslims without regard to the denominational affiliation within each community.[236]

LGBT rights

Male homosexuality is illegal in Lebanon.[237] Discrimination against LGBT people in Lebanon is widespread.[238][239] According to 2019 survey by the Pew Research Center, 85% of Lebanese respondents believe that homosexuality should not be accepted by society.[240]

A gender and sexuality conference, held annually in Lebanon, since 2013, was moved abroad in 2019 after a religious group on Facebook called for the organizers' arrest and the cancellation of the conference for "inciting immorality." General Security Forces shut down the 2018 conference and indefinitely denied non-Lebanese LGBT activists who attended the conference permission to re-enter the country.[241]

Economy

Lebanon's constitution states that 'the economic system is free and ensures private initiative and the right to private property'. Lebanon's economy follows a laissez-faire model.[242] Most of the economy is dollarized, and the country has no restrictions on the movement of capital across its borders.[242] The Lebanese government's intervention in foreign trade is minimal.[242] The Investment Development Authority of Lebanon was established with the aim of promoting investment in Lebanon. In 2001, Investment Law No.360[243] was enacted to reinforce the organisation's mission.

Lebanon is now suffering the worst economic crisis in decades.[148][149] As of 2023, the GDP has shrunk by 40% since 2018, and the currency has experienced a significant depreciation of 95%.[244] The annual inflation rate exceeds 200%, rendering the minimum wage equivalent to approximately $1 per day.[245] This was the first time Lebanon had devalued its official exchange rate in 25 years.[167] According to the United Nations, three out of every four Lebanese individuals fall below the poverty line.[245] The crisis stems from a long-term Ponzi scheme by the Central Bank of Lebanon, borrowing dollars at high interest rates to sustain deficits and maintain a currency peg. By 2019, insufficient new deposits led to an unsustainable situation, resulting in weeks-long bank closures, arbitrary capital controls, and ultimately, the country's default in 2020.[246]

Throughout the Ottoman and French mandatory periods and into the 1960s, Lebanon experienced prosperity, serving as a hub for banking, financial services, and a key distribution center for the Middle East. The local economy thrived with a foundation in industries related to food processing, clothing, jewelry, and carpets. This prosperity was later marred by four decades of conflict.[206] Following the end of the civil war, Lebanon has developed a service-based economy centered around finance, real estate, and tourism.[247] Nearly 65% of the Lebanese workforce attain employment in the services sector.[248] The GDP contribution, accordingly, amounts to roughly 67.3% of the annual Lebanese GDP.[14] However, dependence on the tourism and banking sectors leaves the economy vulnerable to political instability.[249]

The urban population in Lebanon is noted for its commercial enterprise.[250] Emigration has yielded Lebanese "commercial networks" throughout the world.[251] In 2008, Remittances from Lebanese abroad totalled $8.2 billion[252] and account for one-fifth of the country's economy.[253] In 2005, Lebanon had the largest proportion of skilled labor among Arab States.[254]

Agriculture

The agricultural sector in Lebanon employs 20–25% of the total workforce,[255] and contributed 3.1% to the country's GDP,[256] as of 2020. Lebanon has the highest proportion of cultivable land in the Arab world.[257] Major crops include apples, peaches, oranges, and lemons.[14] A significant portion of the country's factories, approximately one-third, is dedicated to producing packaged food items, ranging from poultry to pickles.[255] However, despite favorable conditions for farming and diverse microclimates, the country depends on food imports, constituting 80% of its consumption. This is mainly attributed to the small scale of many farms, preventing the benefits of economies of scale.[255] The ongoing economic crisis and devaluation of the Lebanese pound have also negatively impacted the agricultural sector, particularly through elevated costs for essential imports such as seeds and fertilizers. This economic strain compounds existing burdens for farmers, including escalating debts and inefficient agricultural practices. Consequently, farmers are observing a decline in revenues and encountering difficulties in meeting loan repayment obligations.[255][258]

The commodities market in Lebanon includes substantial gold coin production, however according to International Air Transport Association (IATA) standards, they must be declared upon exportation to any foreign country.[259]

Manufacturing and industry

Industry in Lebanon is mainly limited to small businesses that reassemble and package imported parts. In 2004, industry ranked second in workforce, with 26% of the Lebanese working population,[248] and second in GDP contribution, with 21% of Lebanon's GDP.[14]

Oil has recently been discovered inland and in the seabed between Lebanon, Cyprus, Israel and Egypt and talks are underway between Cyprus and Egypt to reach an agreement regarding the exploration of these resources. The seabed separating Lebanon and Cyprus is believed to hold significant quantities of crude oil and natural gas.[260] On 10 May 2013, the Lebanese minister of energy and water clarified that seismic images of the Lebanese sea bed are undergoing detailed explanation of their contents and that up till now, approximately 10% have been covered. Preliminary inspection of the results showed, with over 50% probability, that 10% of Lebanon's exclusive economic zone held up to 660 million barrels of oil and up to 30×1012 cu ft of gas.[261]

Lebanon has a significant drug industry, including both production and trade. Western intelligence estimate an annual production of over 4 million pounds of hashish and 20,000 pounds of heroin, generating profits exceeding $4 billion. In recent decades, Hezbollah has intensified its engagement in the drug economy, with narcotics serving as a significant revenue stream for the group. Despite some of the harvest being retained for local use, a significant amount is smuggled worldwide. Despite ongoing efforts, the government's inability to control the drug-producing Beqaa Valley and address illicit Captagon factories allows for the persistent occurrence of drug trades, impacting Lebanon's economy and regional stability.[262][263][264]

Science and technology

Lebanon was ranked 94th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024, down from 88th in 2019.[265][266][267] Notable scientists from Lebanon include Hassan Kamel Al-Sabbah, Rammal Rammal, and Edgar Choueiri.[268][269]

In 1960, a science club from a university in Beirut started a Lebanese space program called "the Lebanese Rocket Society". They achieved great success until 1966 where the program was stopped because of both war and external pressure.[270][271]

Development

In the 1950s, GDP growth was the second highest in the world. Despite having no oil reserves, Lebanon, as the Arab world's banking center[272] and among its trading center, had a high national income.[273]

The 1975–1990 civil war heavily damaged Lebanon's economic infrastructure,[224] cut national output by half, and all but ended Lebanon's position as a West Asian entrepôt and banking hub.[10] The subsequent period of relative peace enabled the central government to restore control in Beirut, begin collecting taxes, and regain access to key port and government facilities. Economic recovery has been helped by a financially sound banking system and resilient small- and medium-scale manufacturers, with family remittances, banking services, manufactured and farm exports, and international aid as the main sources of foreign exchange.[274]

Until July 2006, Lebanon enjoyed considerable stability, Beirut's reconstruction was almost complete,[275] and increasing numbers of tourists poured into the nation's resorts.[276] The economy witnessed growth, with bank assets reaching over 75 billion US dollars,[277] Market capitalization was also at an all-time high, estimated at $10.9 billion at the end of the second quarter of 2006.[277] The month-long 2006 war severely damaged Lebanon's fragile economy, especially the tourism sector. According to a preliminary report published by the Lebanese Ministry of Finance on 30 August 2006, a major economic decline was expected as a result of the fighting.[278]

Over the course of 2008 Lebanon rebuilt its infrastructure mainly in the real estate and tourism sectors, resulting in a comparatively robust post war economy. Major contributors to the reconstruction of Lebanon include Saudi Arabia (with US$1.5 billion pledged),[279] the European Union (with about $1 billion)[280] and a few other Persian Gulf countries with contributions of up to $800 million.[281]

Tourism

The tourism industry accounts for about 10% of GDP.[282] Lebanon attracted around 1,333,000 tourists in 2008, thus placing it as 79th out of 191 countries.[283] In 2009, The New York Times ranked Beirut the No. 1 travel destination worldwide due to its nightlife and hospitality.[284] In January 2010, the Ministry of Tourism announced that 1,851,081 tourists had visited Lebanon in 2009, a 39% increase from 2008.[285] In 2009, Lebanon hosted the largest number of tourists to date, eclipsing the previous record set before the Lebanese Civil War.[286] Tourist arrivals reached two million in 2010, but fell by 37% for the first 10 months of 2012, a decline caused by the war in neighbouring Syria.[282]

In 2011, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Japan were the three most popular origin countries of foreign tourists to Lebanon.[287] In summer, a considerable number of visitors to Lebanon consists of Lebanese expatriates coming to visit their hometowns.[246] In 2012, it was reported that an influx of Japanese tourists had caused a rise in popularity of Japanese cuisine in Lebanon.[288]

Demographics

The population of Lebanon was estimated to be 5,592,631 in 2021, with the number of Lebanese nationals estimated to be 4,680,212 (July 2018 est.);[289][290] however, no official census has been conducted since 1932 due to the sensitive confessional political balance between Lebanon's various religious groups.[291] Identifying all Lebanese as ethnically Arab is a widely employed example of panethnicity, as the Lebanese "are descended from many different peoples who are either indigenous, or have occupied, invaded, or settled this corner of the world", making Lebanon, "a mosaic of closely interrelated cultures".[d][294]

The fertility rate fell from 5.00 in 1971 to 1.75 in 2004. Fertility rates vary considerably among the different religious groups: in 2004, it was 2.10 for Shiites, 1.76 for Sunnis and 1.61 for Maronites.[295]

Lebanon has witnessed a series of migration waves: over 1,800,000 people emigrated from the country in the 1975–2011 period.[295] Millions of people of Lebanese descent are spread throughout the world, especially in Latin America.[296] Brazil and Argentina have large expatriate population.[297] (See Lebanese people). Large numbers of Lebanese migrated to West Africa,[298] particularly to the Ivory Coast (home to over 100,000 Lebanese)[299] and Senegal (roughly 30,000 Lebanese).[300] Australia is home to over 270,000 Lebanese (1999 est.).[301] In Canada, there is also a large Lebanese diaspora of approximately 250,000–700,000 people having Lebanese descent. (see Lebanese Canadians). The United States also has one the largest Lebanese population, at around 2,000,000.[302] Another region with a significant diaspora are Gulf Countries, where the countries of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar (around 25,000 people),[303] Saudi Arabia and UAE act as host countries to many Lebanese. 269,000 Lebanese citizens currently reside in Saudi Arabia.[304] Around a third of the Lebanese workforce, about 350,000, live in Gulf countries according to some sources.[305] Over 50% of the Lebanese diaspora are Christian, partly due to the large period of Christian emigration before 1943.[306]

As of 2012[update], Lebanon was host to over 1,600,000 refugees and asylum seekers: 449,957 from Palestine,[10] 100,000 from Iraq,[307] over 1,100,000 from Syria,[10][308] and at least 4,000 from Sudan.[309] According to the Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia of the United Nations, among the Syrian refugees, 71% live in poverty.[310] A 2013 estimate by the United Nations put the number of Syrian refugees at over 1,250,000.[128]

In the last three decades, lengthy and destructive armed conflicts have ravaged the country. The majority of Lebanese have been affected by armed conflict; those with direct personal experience include 75% of the population, and most others report suffering a range of hardships. In total, almost the entire population (96%) has been affected in some way – either personally or because of the wider consequences of armed conflict.[311]

Largest cities or towns in Lebanon

Source? | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Governorate | Pop. | Rank | Name | Governorate | Pop. | ||

Beirut  Tripoli |

1 | Beirut | Beirut | 1,916,100 | 11 | Nabatieh | Nabatieh | 50,000 |  Jounieh  Zahlé |

| 2 | Tripoli | North | 1,150,000 | 12 | Zgharta | North | 45,000 | ||

| 3 | Jounieh | Mount Lebanon | 450,000 | 13 | Bint Jbeil | Nabatieh | 30,000 | ||

| 4 | Zahlé | Beqaa | 130,000 | 14 | Bsharri | North | 25,000 | ||

| 5 | Sidon | South | 110,000 | 15 | Baakleen | Mount Lebanon | 20,000 | ||

| 6 | Aley | Mount Lebanon | 100,000 | ||||||

| 7 | Tyre | South | 85,000 | ||||||

| 8 | Byblos | Mount Lebanon | 80,000 | ||||||

| 9 | Baalbek | Baalbek-Hermel | 70,000 | ||||||

| 10 | Batroun | North Governorate | 55,000 | ||||||

Religion

Lebanon is the most religiously diverse country in West Asia and the Mediterranean.[313] Because the relative sizes of different religions and religious sects remains a sensitive issue, a national census has not been conducted since 1932.[314] There are 18 state-recognized religious sects – four Muslim, 12 Christian, one Druze, and one Jewish.[314] The Lebanese government counts its Druze citizens as part of its Muslim population,[315] although most Druze today do not identify as Muslims.[316][317]

It is believed that there has been a decline in the ratio of Christians to Muslims over the past 60 years, due to higher emigration rates of Christians, and a higher birth rate in the Muslim population.[314] When the last census was held in 1932, Christians made up 53% of Lebanon's population.[295] In 1956, it was estimated that the population was 54% Christian and 44% Muslim.[295]

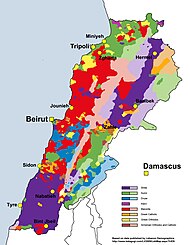

A demographic study conducted[when?] by the research firm Statistics Lebanon found that approximately 27% of the population was Sunni, 27% Shia, 21% Maronite, 8% Greek Orthodox, 5% Druze, 5% Melkite, and 1% Protestant, with the remaining 6% mostly belonging to smaller non-native to Lebanon Christian denominations.[314] The CIA World Factbook estimates (2020) the following (data does not include Lebanon's sizable Syrian and Palestinian refugee populations): Muslim 67.8% (31.9% Sunni, 31.2% Shia, smaller percentages of Alawites and Ismailis), Christian 32.4% (Maronite Catholics are the largest Christian group), Druze 4.5%, and very small numbers of Jews, Baha'is, Buddhists, and Hindus.[318] Other sources like Euronews[319] or the Madrid-based diary La Razón[320] estimate the percentage of Christians to be around 53%. A study based on voter registration numbers shows that by 2011, the Christian population was stable compared to that of previous years, making up 34.35% of the population; Muslims, the Druze included, were 65.47% of the population.[321] The World Values Survey of 2014 put the percentage of atheists in Lebanon at 3.3%.[322] Survey data indicates a decrease in religious faith within Lebanon, especially noticeable among young people.[323]

The Sunni residents primarily live in Western Beirut, the Southern coast of Lebanon, and Northern Lebanon.[324] The Shi'a residents primarily live in Southern Beirut, the Beqaa Valley, and Southern Lebanon.[324] The Maronite Catholic residents primarily live in Eastern Beirut and around Mount Lebanon.[324] The Greek Orthodox residents primarily live in the Koura region, Akkar, Metn, and Beirut (Achrafieh).[325][326] The Melkite Catholic residents live mainly in Beirut, on the eastern slopes of the Lebanon mountains, and in Zahlé.[327] The Druze residents are concentrated in the rural, mountainous areas east and south of Beirut.

Language

Article 11 of Lebanon's Constitution states that "Arabic is the official national language. A law determines the cases in which the French language is to be used".[1] The majority of Lebanese people speak Lebanese Arabic, which is grouped in a larger category called Levantine Arabic, while Modern Standard Arabic is mostly used in magazines, newspapers, and formal broadcast media. Lebanese Sign Language is the language of the Deaf community.

There is also significant presence of French, and of English. Almost 40% of Lebanese are considered francophone, and another 15% "partial francophone", and 70% of Lebanon's secondary schools use French as a second language of instruction.[328] By comparison, English is used as a secondary language in 30% of Lebanon's secondary schools.[328] The use of French is a legacy of France's historic ties to the region, including its League of Nations mandate over Lebanon following World War I; as of 2005[update], some 20% of the population used French on a daily basis.[329] The use of Arabic by Lebanon's educated youth is declining, as they usually prefer to speak in French and, to a lesser extent, English, which are seen as more fashionable.[330][331]

English is increasingly used in science and business interactions.[332][333] Lebanese citizens of Armenian, Greek, or Assyrian descent often speak their ancestral languages with varying degrees of fluency. As of 2009[update], there were around 150,000 Armenians in Lebanon, or around 5% of the population.[334]

Education

According to surveys from the World Economic Forum's 2013 Global Information Technology Report, Lebanon has been ranked globally as the fourth best country for math and science education, and as the tenth best overall for quality of education. In quality of management schools, the country was ranked 13th worldwide.[335]

The United Nations assigned Lebanon an education index of 0.871 in 2008. The index, which is determined by the adult literacy rate and the combined primary, secondary, and tertiary gross enrollment ratio, ranked the country 88th out of the 177 countries participating.[336] All Lebanese schools are required to follow a prescribed curriculum designed by the Ministry of Education. Some of the 1400 private schools offer IB programs,[337] and may also add more courses to their curriculum with approval from the Ministry of Education. The first eight years of education are, by law, compulsory.[14]

Lebanon has forty-one nationally accredited universities, several of which are internationally recognized.[338][339] The American University of Beirut (AUB) and the Saint Joseph University of Beirut (USJ) were the first Anglophone and the first Francophone universities to open in Lebanon, respectively.[340][341]

Universities in Lebanon, both public and private, largely operate in French or English.[342] The top-ranking universities in the country are the American University of Beirut (#2 in the Middle East as of 2022 and #226 worldwide),[343] University of Balamand (#17 in the region and #802–850 worldwide),[344] Lebanese American University (#17 in the region and #501 worldwide),[345] Université Saint Joseph de Beyrouth (#2 in Lebanon and #631–640 worldwide),[346] Université Libanaise (#577 worldwide) and Holy Spirit University of Kaslik (#600s worldwide as of 2020).[347] Notre Dame University-Louaize (NDU) (#701 as of 2021).[348]

Health

In 2010, spending on healthcare accounted for 7.03% of the country's GDP. In 2009, there were 31.29 physicians and 19.71 nurses per 10,000 inhabitants.[349] The life expectancy at birth was 72.59 years in 2011, or 70.48 years for males and 74.80 years for females.[350] By the end of the civil war, only one-third of the country's public hospitals were operational, each with an average of 20 beds. By 2009, the country had 28 public hospitals, with a total of 2,550 beds.[351] At public hospitals, hospitalized uninsured patients pay 5% of the bill, in comparison with 15% in private hospitals, with the Ministry of Public Health reimbursing the remainder.[351] The Ministry of Public Health contracts with 138 private hospitals and 25 public hospitals.[352]

In 2011, there were 236,643 subsidized admissions to hospitals; 164,244 in private hospitals, and 72,399 in public hospitals. More patients visit private hospitals than public hospitals, because the private beds supply is higher.[352] According to the Ministry of Public Health in Lebanon, the top 10 leading causes of reported hospital deaths in 2017 were: malignant neoplasm of bronchus or lung (4.6%), Acute myocardial infarction (3%), pneumonia (2.2%), exposure to unspecified factor, unspecified place (2.1%), acute kidney injury (1.4%), intra-cerebral hemorrhage (1.2%), malignant neoplasm of colon (1.2%), malignant neoplasm of pancreas (1.1%), malignant neoplasm of prostate (1.1%), malignant neoplasm of bladder (0.8%).[353]

Recently,[when?] there has been an increase in foodborne illnesses in Lebanon. This has raised public awareness on the importance of food safety, including in the realms of food storage, preservation, and preparation. More restaurants are seeking information and compliance with International Organization for Standardization.[354]

Mental health