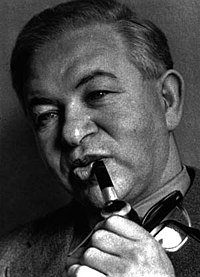

Arne Jacobsen

Arne Emil Jacobsen | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 11 February 1902 Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Died | 24 March 1971 (aged 69) Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Nationality | Danish |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards | C. F. Hansen Medal (1955) |

| Buildings | Bellevue Theatre SAS Royal Hotel Aarhus City Hall St Catherine's College Danmarks Nationalbank |

Arne Emil Jacobsen, Hon. FAIA (Danish pronunciation: [ˈɑːnə e̝ˈmiˀl ˈjɑkʰʌpsn̩]; 11 February 1902 – 24 March 1971) was a Danish architect and furniture designer. He is remembered for his contribution to architectural functionalism and for the worldwide success he enjoyed with simple well-designed chairs.

Biography

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]Arne Jacobsen was born on 11 February 1902 in Copenhagen.[1] His father Johan was a wholesale trader in safety pins and snap fasteners. His mother Pouline was a bank teller whose hobby was floral motifs.[2] He is of Jewish descent.[3] He first hoped to become a painter, but was dissuaded by his mother, who encouraged him to opt instead for the more secure domain of architecture. After a spell as an apprentice mason, Jacobsen was admitted to the Architecture School at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts where from 1924 to 1927 he studied under Kay Fisker and Kaj Gottlob, both leading architects and designers.[4]

Still a student, in 1925 Jacobsen participated in the Paris Art Deco fair, Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, where he won a silver medal for a chair design.[5] On that trip, he was struck by the pioneering aesthetic of Le Corbusier's L'Esprit Nouveau pavilion. Before leaving the Academy, Jacobsen also travelled to Germany, where he became acquainted with the rationalist architecture of Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius. Their work influenced his early designs including his graduation project, an art gallery, which won him a gold medal.[6] After completing architecture school, he first worked at city architect Poul Holsøe's architectural practice.[7]

In 1929, in collaboration with Flemming Lassen, he won a Danish Architect's Association competition for designing the "House of the Future" which was built full scale at the subsequent exhibition in Copenhagen's Forum.[8] It was a spiral-shaped, flat-roofed house in glass and concrete, incorporating a private garage, a boathouse and a helicopter pad. Other striking features were windows that rolled down like car windows, a conveyor tube for the mail and a kitchen stocked with ready-made meals.[9] A Dodge Cabriolet Coupé was parked in the garage, there was a Chris Craft in the boathouse and an Autogyro on the roof.[10] Jacobsen immediately became recognised as an ultra-modern architect.

Pre-World War II career

[edit]

The year after winning the "House of the Future" award, Arne Jacobsen set up his own office. He designed the functionalist Rothenborg House, which he planned in every detail, a characteristic of many of his later works.[11]

Soon afterwards, he won a competition from Gentofte Municipality for the design of a seaside resort complex in Klampenborg on the Øresund coast just north of Copenhagen. The various components of the resort became his major public breakthrough in Denmark, further establishing him as a leading national proponent of the International Modern Style. In 1932, the first item, the Bellevue Sea Bath, was completed. Jacobsen designed everything from the characteristic blue-striped lifeguard towers, kiosks and changing cabins to the tickets, season cards and even the uniforms of the employees.[12] The focal point of the area was supposed to have been a lookout tower, more than a hundred metres high with a revolving restaurant at the top but it was abandoned after huge local protests. Still, it is reflected in the overall arrangement of buildings in the area which all follow lines that extend from their missing centre. In 1934, came the Bellavista residential development, built in concrete, steel and glass, with smooth surfaces and open floor planning, free of any excesses or ornaments. Completing the white trilogy in 1937, the Bellevue Theatre featured a retractable roof allowing open-air performances.[12] These early works clearly show the influence of the White Cubist architecture Jacobsen had encountered in Germany, particularly at the Weissenhof Estate in Stuttgart. The cluster of white buildings at Bellevue also includes the Skovshoved Filling Station. In their day, these projects were described as "The dream of the modern lifestyle".[13]

Despite considerable public opposition to his avant-garde style, Jacobsen went on to build Stelling House on Gammeltorv, one of Copenhagen's most historic squares. Although the modernistic style is rather restrained and was later seen as a model example of building in a historic setting, it caused virulent protests in its day. One newspaper wrote that Jacobsen ought to be "banned from architecture for life".[14]

When, together with Erik Møller, he won a competition for the design of Århus City Hall it was with yet another controversial design. It was deemed too modern and too anti-monumental. In the end Jacobsen had to add a tower as well as marble cladding.[15] Still, it is considered one of his most important buildings. It consists of three offset volumes.

World War II exile and return

[edit]

During World War II, scarcity of building materials and Nazi racial laws against Jewish citizens made assignments difficult to obtain. In 1943, due to his Jewish background, Arne Jacobsen had to flee his office and go into exile to escape the Nazis' planned deportation of Jewish Danes to concentration camps. Along with other Jewish Danes and with the help of the Danish resistance, he fled Denmark, rowing a small boat across Øresund to neighboring Sweden where he would stay for the next two years. His architectural work was limited to a summer house for two doctors.[6] Instead he spent his time designing fabrics and wallpaper.

When the war ended in 1945, Jacobsen returned to Denmark and resumed his architectural career. The country was in urgent need of both housing and new public buildings but the primary need was for spartan buildings which could be built without delay.

After some years Jacobsen got his career back on track and with projects such as the Allehusene complex from 1952 and his Søholm terraced houses from 1955, he embarked on a more experimental phase. He moved into one of the Søholm houses and lived there until his death.[16]

Rødovre Town Hall, built from 1952 to 1956, shows how well Jacobsen combined the use of different materials: sandstone, two types of glass, painted metalwork and stainless steel. It is also noted for its central staircase, suspended from the roof on orange-red steel rods. The sides are cut from 5 cm steel plate, painted a dark grey; the steps, only a few millimeters thick, are stainless steel with a rubber coating on the upper side for better grip.

The Munkegaard School consists of pavilions connected by glass corridors, arranged in a grid system around small courtyards. It received considerable attention in international school circles and contributed to his growing international reputation.[17][18]

Large commissions

[edit]With the SAS Royal Hotel, built from 1956 to 1960, Jacobsen was given the opportunity to design what has been called "the world's first designer hotel."[19] He designed everything from the building and its furniture and fittings to the ashtrays sold in the souvenir shop and the airport buses.

These larger assignments started to attract attention and commissions from abroad. Rødovre Town Hall secured him an invitation for his first competition in Germany which was followed by a number of other German projects.

A delegation of Oxford dons visited the SAS Hotel and the Munkegård School in their search for an architect for St Catherine's College. They were soon convinced he was the right choice for their important commission.[6] Again Jacobsen designed everything, including the garden, down to the choice of fish species for the pond. The dining hall is notable for its Cumbrian slate floor. The original college buildings received a Grade I listing on 30 March 1993.[20] Some individual buildings on the campus also have their own, high, listings, including the Grade I listed bike shed.[21]

Incomplete works

[edit]When Arne Jacobsen died unexpectedly in 1971, he had a number of large projects under way. These included a new town hall in Mainz, Germany, and in Castrop-Rauxel, Germany, the Danish National Bank and the Royal Danish Embassy in London. These projects were completed by Dissing+Weitling, a firm set up by his former key employees Hans Dissing and Otto Weitling.

Furniture and product design

[edit]

Today, Arne Jacobsen is remembered primarily for his furniture designs. However, he believed he was first and foremost an architect. According to Scott Poole, a professor at Virginia Tech, Arne Jacobsen never used the word 'designer', notoriously disliking it.

His way into product design came through his interest in Gesamtkunst and most of his designs which later became famous in their own right were created for architectural projects. One of his first furniture designs was the Paris lounge chair from 1929 which was also displayed as a part of the interior design of his famous “House of the Future". Most of his furniture designs were the result of a cooperation with the furniture manufacturer Fritz Hansen with which he initiated a collaboration in 1934 while his lamps and light fixtures were developed with Louis Poulsen. In spite of his success with his chair at the Paris Exhibition in 1925, it was during the 1950s that his interest in furniture design peaked.

A major source of inspiration stemmed from the bent plywood designs of Charles and Ray Eames. He was also influenced by the Italian design historian Ernesto Rogers, who had proclaimed that the design of every element was equally important "from the spoon to the city" which harmonized well with his own ideals.

In 1951, he created the Ant chair for an extension of the Novo pharmaceutical factory and, in 1955, came the Seven Series. Both matched modern needs perfectly, being light, compact and easily stackable. Two other successful chair designs, the Egg and the Swan, were created for the SAS Royal Hotel which he also designed in 1956.

Jacobsen's greatest contribution to the furniture genre came in 1951-52 with his three-legged "Ant "chair which was created for functionality being constructed with laminated veneered plywood housed on of chrome legs that were condensed and stackable for economy of space.[22]

Other designs were made for Stelton, a company founded by his foster son Peter Holmbl. These include the now classic Cylinda Line stainless steel cocktail kit and tableware.

Other interior design is a line of faucets and accessories for bathroom and kitchen, created after he won a competition in 1961 for his design of the National Bank of Denmark. This classic design is still in production today by Danish company Vola.

Style and legacy

[edit]According to R. Craig Miller, author of "Design 1935–1989, What Modern was", Jacobsen's work "is an important and original contribution both to modernism and to the specific place Denmark and the Scandinavian countries have in the modern movement" and continues "One might in fact argue that much of what the modern movement stands for, would have been lost and simply forgotten if Scandinavian designers and architects like Arne Jacobsen would not have added that humane element to it".[9]

Arne Jacobsen is noted for his sense of proportion. Indeed, he himself saw this as one of the main features of his work. In an interview he said; "The proportion is exactly what makes the beautiful ancient Egyptian temples [...] and if we look at some of the most admired buildings of the Renaissance and Baroque, we notice that they were all well-proportioned. Here is the basic thing".[9]

Selected works

[edit]

Architecture

[edit]- Bellevue Beach, Klampenborg, Denmark (1932)

- Bellavista residential complex, Klampenborg, Copenhagen (1931–34)

- Bellevue Theatre and restaurant, Klampenborg (1935–36)

- Skovshoved Petrol Station, Skovshoved, Copenhagen (1936)

- Stelling House, 6 Gammeltorv, Copenhagen (1934–37)

- Søllerød Town Hall (with Flemming Lassen), Søllerød, Copenhagen (1938–42)

- Århus City Hall (with Erik Møller), Århus (1939–42)

- Søholm I (1946–50),[16] II[23] and III[24] terraced houses, Klampenborg

- Rødovre Town Hall, Rødovre, Denmark (1952–56)

- Alléhusene housing, Gentofte, Copenhagen (1949–1953)

- Glostrup Town Hall, Glostrup, Copenhagen (1958)

- Munkegaard School, Copenhagen (1957)

- SAS Royal Hotel, Copenhagen (1958–60)

- Toms Chocolate Factory, Ballerup, Copenhagen (1961)

- National Bank of Denmark, Copenhagen (1965–70)

- Landskrona Sports-Hall, Landskrona, Sweden (1965)

- St Catherine's College, Oxford, UK (1964–66)

- Mainz City Hall, Mainz, Germany (1966–73)

- Castrop-Rauxel Town Hall and Forum, Castrop-Rauxel, Germany (1966–76)[25]

- Christianeum School, Hamburg, Germany (1970–71)

- HEW Vattenfall Europe, Hamburg, Germany (1970)[26]

- Royal Danish Embassy, London, UK (1976–77)[27]

Furniture and product design

[edit]- Paris Lounge Chair (1929)

- Charlottenborg Lounge Chair / A.J 237 (1936)

- Charlottenborg Sofa and Charlottenborg Coffee Table (1937)

- Ant chair (1952)

- Dot Stool Model 3170 (1954)

- Tongue chair (1955)

- Series 7 chairs

- Swan chair (1958)

- Egg chair (1958)

- Pot chair (1959)

- Giraffe chair (1959)

- Cylinda Line tableware

- Flatware cutlery (1957)

- VOLA (1968)

- Dot Stool Model M3170 (1969)

- Drop chair

In culture and media

[edit]- Arne Jacobsen's No. 7 chair is known for being the prop used to hide Christine Keeler's nakedness in the iconic photograph of her taken by Lewis Morley in 1963.[28] Morley just happened to use a chair that he had in the studio, which turned out to have been a copy of Jacobsen's design. Since then 'Number 7' chairs have been used for many similar portraits imitating the pose.

- The Seven has featured on the set of the BBC soap opera EastEnders.[6]

- Jacobsen's flatware design, with right and left-handed spoons, is used by Stanley Kubrick in his movie 2001: A Space Odyssey. It was selected for the film because of its 'futuristic' appearance.

- Arne Jacobsen's grandson, Tobias Jacobsen, is also a designer for furniture; he created for example the chair "Vio" (according to the elements of a violin) and the sideboard "Boomerang" (named after the curved throw stick).[29]

There are chairs with his design at gate 56A at the San Francisco airport.

Awards and recognition

[edit]- 1955 C. F. Hansen Medal

- 1957 Grand prix, Milan XI Triennale, Italy, for Grand Prix chair

- 1961 Honorary DLitt, Oxford University[30]

- 1962 Prince Eugen Medal for architecture [31]

- 1967 ID-prize, Danish Society of Industrial Design, for Cylinde

- 1968 International Design Award, American Institute of Interior Designers, US, for Cylinde

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Arne Jacobsen | Danish architect". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ Biography from Arne-Jacobsen.com.

- ^ "Biography – Arne Jacobsen Design". Arne Jacobsen. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "Arne Jacobsen". answers.com. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ Fiell, Charlotte; Fiell, Peter (2005). Design of the 20th Century (25th anniversary ed.). Köln: Taschen. p. 354. ISBN 9783822840788. OCLC 809539744.

- ^ a b c d "Arne Jacobsen". Design Museum. Archived from the original on 5 January 2010. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ "Arne Jacobsen". Ketterer Kunst. Archived from the original on 13 October 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ Shop, Finnish Design. "Arne Jacobsen design". www.finnishdesignshop.com. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ a b c "Biography + Resources: Egg Chair designer Arne Jacobsen". Fritz Hansen. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ^ "Jacobsen's light". Louis Poulsen. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ "Rothenborgs Hus". Gentofte Municipality. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- ^ a b "Arne Jacobsens betagende Bellevue og Bellavista". Villabyerne. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ^ "Arne Jacobsen -Restaurant Jacobsen". arcspace. Archived from the original on 8 March 2010. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ^ "Arne Jacobsen – Absolutely Modern". arcspace. Archived from the original on 21 October 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ^ "ÅRHUS RÅDHUS (1942". Danish Architecture Center. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ^ a b "ARNE JACOBSEN'S OWN HOUSE" (PDF). Realea. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ^ "Munkegårdsskolen". arnejacobsen.gen. Archived from the original on 7 April 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ^ "Munkegårdsskolen". Danish Architecture Centre. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ^ Kaminer, Michael (12 July 2009). "Where the Rooms Are the View". The Washington Post. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ "Listed Buildings Online – St Catherines College, Podium And All Buildings Upon It". Heritage Gateway. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- ^ Historic England. "St Catherine's College Bicycle Store (Grade I) (1229973)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ^ Hackney, Rod (Autumn 1972). "Arne Jacobsen: Architecture and Fine Art". Leonardo. 5 (4). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press: 307–313. doi:10.2307/1572585. ISSN 0024-094X. JSTOR 1572585. OCLC 5547939901. Retrieved 2 October 2024.

- ^ "Søholm 2". Gentofte Municipality. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ^ "Rækkehusene Søholm III". Gentofte Municipality. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ^ Designed together with Otto Weitling, who oversaw the construction from Jacobsens death in 1971 onward.|url=http://www.baukunst-nrw.de/objekte/Forum-und-Rathaus-Castrop-Rauxel--281.htm |

- ^ Believed to have been notably successful.

- ^ The dates here represent the period of construction only.

- ^ Christine Keeler Photograph: A Modern Icon – Victoria and Albert Museum

- ^ Designerprofile Tobias Jacobsen, D: Fashion For Home, retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ "Who's Who in the Twentieth Century". Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "Prins Eugen Medaljen" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Dyssegaard, Søren (ed.); Jacobsen, Arne; Skriver, Poul Erik: Arne Jacobsen, a Danish architect, (translation: Reginald Spink and Bodil Garner), 1971, Copenhagen: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 56 p. ISBN 87-85112-00-3

- Jacobsen, Arne: Arne Jacobsen: absolutely modern, 2002, Humlebaek: Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, 96 p. ISBN 87-90029-74-7

- Solaguren-Beascoa de Corral, Félix: Arne Jacobsen (Obras y Proyectos / Works and Projects), 1992, Barcelona, Editorial Gustavo Gili, 222 pages. ISBN 84-252-1404-1

- Thau, Carsten; Vindum, Kjeld: Arne Jacobsen, 2008, Copenhagen, Arkitektens forlag, 560 p. ISBN 978-87-7407-230-0

- Solaguren-Beascoa de Corral, Félix: "Jacobsen. Objects and Furniture Design", 2010, Barcelona, Ed. Poligrafa, 127 pages. ISBN 978-84-343-1183-1 / 978-84-343-11834-8

- Solaguren-Beascoa de Corral, Félix: "Arne Jacobsen. Edificios Públicos. Public Buildings", 2010, Barcelona, Ed. Gustavo Gili, 144 pages. ISBN 84-252-2011-4

- Solaguren-Beascoa de Corral, Félix: "Arne Jacobsen: Approach to his Complete Works. 1926–1949" link to Ed. Arkitektens Forlag, 2002, Copenhague, Ed. Arkitektens Forlag, 204 pages. ISBN 87-7407-2706

- Solaguren-Beascoa de Corral, Félix: "Arne Jacobsen: Approach to his Complete Works. 1950–1971" link to Ed. Arkitektens Forlag, 2002, Copenhague, Ed. Arkitektens Forlag, 276 pages. ISBN 87-7407-2706

- Solaguren-Beascoa de Corral, Félix: "Arne Jacobsen. Drawings 1958–1965", 2002, Copenhague, Ed. Arkitektens Forlag, 192 pages. ISBN 87-7407-2706

- Solaguren-Beascoa de Corral, Félix: "Arne Jacobsen", 2005, Pekin, Ed. China National Publications, 222 pages. ISBN 7-5381-4439-0

External links

[edit]- Arne Jacobsen at archINFORM

- Reflections on a Soup Spoon by Alice Rawsthorn, International Herald Tribune, May 14 2012

- Arne Jacobsen

- Danish textile designers

- 1902 births

- 1971 deaths

- Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts alumni

- Danish designers

- Danish furniture designers

- Functionalist architects

- Modernist designers

- Modernist architects from Denmark

- Architects from Copenhagen

- Designers from Copenhagen

- Honorary Fellows of the American Institute of Architects

- Jewish architects

- Jewish Danish designers

- Arne Jacobsen buildings

- Recipients of the Eckersberg Medal

- Recipients of the C.F. Hansen Medal

- 20th-century American architects

- Recipients of the Prince Eugen Medal

- 20th-century Danish Jews

- Danish design

- Danish modern