Armenian carpet

The term Armenian carpet (Armenian: Հայկական գորգ; haykakan gorg) designates, but is not limited to, tufted rugs or knotted carpets woven in Armenia or by Armenians from pre-Christian times to the present.[1][2][3] It also includes a number of flat woven textiles. The term covers a large variety of types and sub-varieties. Due to their intrinsic fragility, almost nothing survives—neither carpets nor fragments—from antiquity until the late medieval period.

Traditionally, since ancient times the carpets were used in Armenia to cover floors, decorate interior walls, sofas, chairs, beds and tables.[4] Up to present the carpets often serve as entrance veils, decoration for church altars and vestry. Starting to develop in Armenia as a part of everyday life, carpet weaving was a must in every Armenian family, with the carpet making and rug making being almost women's occupation.[5] Armenian carpets are unique "texts" composed of the ornaments where sacred symbols reflect the beliefs and religious notions of the ancient ancestors of the Armenians that reached us from the depth of centuries. The Armenian carpet and rug weavers preserved strictly the traditions. The imitation and presentation of one and the same ornament-ideogram in the unlimited number of the variations of styles and colors contain the basis for the creation of any new Armenian carpet. In this relation, the characteristic trait of Armenian carpets is the triumph of the variability of ornaments that is increased by the wide gamut of natural colors and tints.

Etymology of word "carpet" in the Armenian and other languages

[edit]The Armenian words for carpet are "karpet" (Armenian: կարպետ)[6] or "gorg" (Armenian: գորգ).[7] Though both words in Armenian are synonymous, word "karpet" is mostly used for non-pile rugs and "gorg" is for a pile carpet.

Two of the most frequently used terms to designate woven woolen floor coverings emanate directly from the Armenian experience: carpet and kali/khali. The term "kapert" (Armenian: կապերտ), formed of root "kap" (Armenian: կապ) that means "knot",[8][9] later to become "karpet" (Armenian: կարպետ) in colloquial Armenian, is used in the 5th-century Armenian translation of the Bible (Matthew 9:16 and Mark 2:21).[10] It is assumed that the word "carpet" entered into French (French: carpette) and English (English: carpet) in the 13th century (through Medieval Latin carpita, meaning "thick woolen cloth") [11] as a consequence of the trade in rugs through the port cities of the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia. Francesco Balducci Pegolotti, a Florentine merchant stationed in Cyprus, reported in his La pratica della mercatura that from 1274 to 1330, carpets (kaperts) were imported from the Armenian cities of Ayas and Sis to Florence.[12]

Armenian word "gorg" (Armenian: գորգ) is first mentioned in written sources in the 13th century. This word ("gorg") is in the inscription that was cut out in the stone wall of Kaptavan Church in Artsakh (Karabagh) and is dated by 1242—1243 AD.[13][14] Grigor Kapantsyan, professor of Armenian Studies, considered that Armenian "gorg" (Armenian: գորգ) is a derivative of Hittite-Armenian vocabulary, where it existed in the forms of "koork" and "koorkas". Edgar H. Sturtevant, an expert in Hittite studies, explains the etymology of word "koork"/"koorkas" as "horse cloth".[15]

As for the Persian "qali", which entered into Turkish as "qali" or as "khali" in Anatolia Ottoman Turkish and Armenian,[16] it derives from the city of Theodosiopolis-Karin-Erzerum, known to the Arabs as Qali-qala from the Armenian "Karnoy k‘aghak", the "city of Karin". The name "Erzerum" itself, as is well known, is of Armenian origin from the usage Artzen ar-Rum. This latter term came into being after the destruction of the important Armenian commercial center of Artzen, 15 kilometers east of Theodosiopolos-Karin, by the Seljuks in 1041 after which the inhabitants fled to Karin, then in Rum, that is in Byzantine territory, renaming it Artzen in Rum or Arzerum/Erzerum/Erzurum.[17]

Label of Armenian Carpet in the Western world

[edit]The designation "Armenian Carpet" in the English language has existed since the 1850s.[18] It appeared in Western scholarly works in the latter part of the 19th century as attested in the writings of the Austrian art historian Alois Riegl, who mentioned an Armenian carpet created in 1202.[18]

History

[edit]

19-20th centuries

The art of the Armenian carpet and rug weaving has its roots in ancient times. However, due to the fragile nature of carpets very few examples have survived. Only one specimen has been discovered from the ancient (pre-Christian) period and relatively few specimens are in existence from the early medieval period which can be found in private collections as well as various museums throughout the world.

"The complex history of Armenian weaving and needlework was acted out in the Near East, a vast, ancient, and ethnically diverse region. Few are the people who, like the Armenians, can boast of a continuous and consistent record of fine textile production from the 1st millennium BC to the present. Armenians today are blessed by the diversity and richness of a textile heritage passed on by thirty centuries of diligent practice; yet they are burdened by the pressure to keep alive a tradition nearly destroyed in the Armenian genocide of 1915, and subverted by a technology that condemns handmade fabrics to museums and lets machines produce perfect, but lifeless cloth".[19] [20]

Early history

[edit]

Various rug fragments have been excavated in Armenia dating back to the 7th century BC or earlier. Complete rugs, or nearly complete rugs of this period have not yet been found. The oldest, single, surviving knotted carpet in existence is the Pazyryk carpet, excavated from a frozen tomb in Siberia, dated from the 5th to the 3rd century BC, now in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. Although claimed by many cultures, this square tufted carpet, almost perfectly intact, is considered by many experts to be of Caucasian, specifically Armenian, origin. The rug is woven using the Armenian double knot, and the red filaments color was made from Armenian cochineal.[21][22] The eminent authority of ancient carpets, Ulrich Schurmann, says of it, "From all the evidence available I am convinced that the Pazyryk rug was a funeral accessory and most likely a masterpiece of Armenian workmanship".[23] Gantzhorn concurs with this thesis. At the ruins of Persepolis in Iran where various nations are depicted as bearing tribute, the horse design from the Pazyryk carpet is the same as the relief depicting part of the Armenian delegation.[24] The historian Herodotus writing in the 5th century BC also informs us that the inhabitants of the Caucasus wove beautiful rugs with brilliant colors which would never fade.[25]

Christian period

[edit]Apart from the Pazyryk carpet, after Armenia declared itself as the first Christian state in 301 AD, carpet making took on a decidedly Christian art form and identity.[26] By the Middle Ages, Armenia was a major exporter of carpets to as far away places as China.[27] In many Medieval Chinese artworks for example, carpets were depicted in which the designs were typically that of Armenian carpets with some even depicting clear Christian crosses. The art of the Armenian carpet during this period evolved alongside Armenian church architecture, Armenian cross-stones and illuminated manuscript art, with typical rug motifs using the same elements of these designs. The cruciform with its variations would eventually come to dominate Armenian carpet designs.[26]

Armenian genocide

[edit]

The period of the Armenian genocide from 1894 to 1923 saw a demographic change in the hitherto Armenian tradition of rug and carpet making in Anatolia (Western Armenia as well as Turkey). Even though carpets from this region had established the commercial name of "Turkish Carpet" there is evidence to suggest that the majority of weavers in the Ottoman Empire were Armenians. However, after 1923, carpet making in the newly established Turkish republic was erroneously declared a "historically Turkish craft" as is claimed, for example, by the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum where many Armenian carpets are depicted as "Turkish or Islamic art".[24]

During the Genocide, in addition to the catastrophic loss of many expert carpet weavers, thousands of Armenian children were also orphaned and the Near East Relief saved many of these children, some of whom ended up in the northern part of Beirut, where a rug factory would be established under the guidance of Dr. Jacob Kuenzler, a Swiss missionary.[28] This factory was established for the purpose of teaching young orphans (mainly girls) rug weaving, so that they may go on making a living later on in their adult lives. Thus for a brief period "orphan-rugs" were created in this factory, the most famous of which was gifted to the White House in 1925, as a gesture of gratitude and good will towards the American people by the orphans. Known as the Armenian Orphan rug, the rug depicts a Biblical Garden of Eden featuring various animals and symbols and measuring 12 feet by 18 feet with 4 million knots. This rug is said to have been made by 400 orphans over a period of 18 months from 1924 to 1925.[29]

Soviet period

[edit]After a short-lived republic Armenia fell to Soviet rule in 1920 and within a short period, carpet making in the Caucasus as well as Central Asia would take a new turn. The Soviet Union commercialized the trade and sponsored much of the production. Thus carpet making went from a mostly home craft to a mostly commercial craft. However, in rural areas the carpet making traditions in some families continued. Although commercial carpet makers were mostly free to practice their art, religious themes were discouraged. During this period the designs on Armenian rugs also changed somewhat, although the overall character remained. Many "Soviet carpets" were also produced depicting Communist leaders.

Modern era

[edit]With the fall of the Soviet Union, carpet making in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh continued. Private companies as well as home workshops were again revived. Among some weavers, the traditional method of using rug motifs from Armenian churches, manuscript art and cross-stones was also revived. After the first Nagorno-Karabakh War some carpet making workshops were formed to help the many displaced Armenians find employment. Today the traditional art of Armenian carpet making is kept alive by weavers in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh using all the methods, techniques and designs from ancient times.[citation needed] This is remarkable considering the history of Armenia. People of Armenian descent who live in other countries also continue the tradition, such as Armenian American Hratch Kozibeyokian, a scholar and third generation weaver who organizes exhibitions focused on Armenian carpet tradition.[30][31]

Development of Armenian carpet and rug weaving

[edit]

Armenian carpet weaving that at the initial period coincided with cloth weaving by execution technique have passed the long path of development, starting from simple fabrics, which had been woven at the braiding frames of various form to pile knotted carpets that became the luxurious and dainty pieces of arts.

Carpet-weaving is historically a major traditional profession for the majority of Armenian women, including many Armenian families. Prominent Karabakh carpet weavers there were men too. The oldest extant Armenian carpet from the region, referred to as Artsakh during the medieval era, is from the village of Banants (near Gandzak) and dates to the early 13th century.[32] The first time that the Armenian word for carpet, gorg, was used in historical sources was in a 1242-1243 Armenian inscription on the wall of the Kaptavan Church in Artsakh.[33]

Art historian Hravard Hakobyan notes that "Artsakh carpets occupy a special place in the history of Armenian carpet-making."[33] Common themes and patterns found on Armenian carpets were the depiction of dragons and eagles. They were diverse in style, rich in color and ornamental motifs, and were even separated in categories depending on what sort of animals were depicted on them, such as artsvagorgs (eagle-carpets), vishapagorgs (dragon-carpets) and otsagorgs (serpent-carpets).[33] The rug mentioned in the Kaptavan inscriptions is composed of three arches, "covered with vegatative ornaments", and bears an artistic resemblance to the illuminated manuscripts produced in Artsakh.[33]

The art of carpet weaving was in addition intimately connected to the making of curtains as evidenced in a passage by Kirakos Gandzaketsi, a 13th-century Armenian historian from Artsakh, who praised Arzu-Khatun, the wife of regional prince Vakhtang Khachenatsi, and her daughters for their expertise and skill in weaving.[34]

Armenian carpets were also renowned by foreigners who traveled to Artsakh; the Arab geographer and historian Al-Masudi noted that, among other works of art, he had never seen such carpets elsewhere in his life.[35]

On the opinion of various authors that the origin of the oriental carpets and rugs did not have any association with nomadic tribes, and Central Asia. They consider that the "oriental carpet is neither of nomadic origin, nor do its origins lie in Central Asia; it is a product of ancient oriental civilizations in the Armenian Uplands at the crossroads of the oldest trade routes between west, north and south".[24]

The development of carpet and rug weaving in Armenia had been the barest necessity that had been dictated by the climatic conditions of the complete Armenian Highland. The type, size and thickness of carpets and rugs had also depended upon the climate of every specific region within the territory of Armenian Highland.[36] The dwelling houses and other buildings in Armenia were constructed exclusively of stone or were cut in rocks with no wood flooring inside traditionally. This fact was proved by the results of excavations carried out in medieval Armenian cities, such as Dvin, Artashat, Ani and others.[4] There has been the necessary source of raw materials in Armenia, including wool yarn and other fibres, as well as natural dyes.[37] The most widespread raw materials to produce yarn for carpets and rugs was sheep wool, as well as goat wool, silk, flax, cotton and other.

In the 13th and 14th centuries, when the carpet weaving started to develop at Near East, Armenia "was one of the most productive regions" in this regard. It was conditioned by the existence of "good quality wool, pure water and dyes".[38]

One of the most important conditions for the development of carpet and rug weaving was the availability of towns and cities, where the arts and crafts might develop. These cities and towns also served as large commercial centers located on main ancient trade routes that passed by the Armenian Highland, including one of the branches of Silk Road that passed across Armenia.[39]

Abd ar-Rashid al-Bakuvi wrote that "the carpets and as-zalali that are named "kali" are exported from Kalikala (Karin) that was located on the strategic road between Persia and Europe. According to the 13th-century Arab geographer Yaqut al-Hamavi, the origin of the word kali/khali/hali, a knotted carpet, is from one of the early and important Armenian carpet centers, Theodosiopolis, Karin in Armenian, Qaliqala in Arabic, modern Erzerum. He says, "А Qaliqala on fabrique des tapis qu'on nomme qali du nom abrege de la ville".[40][41] Academician Joseph Orbeli directly writes that word "karpet" is of Armenian origin.[42]

Between the tangible reality of the Pazyryk carpet and the Mongol domination of the Near East in the 13th century virtually nothing survives, not even fragments. Our knowledge of oriental rugs is entirely from literary sources. Of these there are three categories: the Arab geographers and historians, who represent the most important witnesses of rug making, the Italian merchants and travelers, and the Armenian historians. The most common term for these Near Eastern floor and wall covering in these sources are Armenian carpets or carpets from Armenia. It is only later, as the Ottomans conquered these areas, including all of Armenian in the 16th century, that the term Turkish carpet began to be used, but that too was replaced in the 19th century by the term Persian rug or carpet because the great commercial agents of England, the U.S., and Germany began setting up looms for quantity weaving in Iran to supply the ever increasing demand for the oriental rug in their countries.

The Medieval Arab sources – al-Baladhuri (a 9th-century Persian historian), Ibn Hawqal (a 10th-century Arab writer, geographer, and chronicler), Yaqut (13th-century Arab geographer), and Ibn Khaldun (a 14th-century Arab polymath) among the most famous – speak regularly about the wonderful Armenian carpets of Qali-qala and the medieval Armenian capital of Dvin ("Dabil" in Arab sources) as well as their use of the Armenian red cochineal dye known in Armenian as vordan karmir ("worm's red"), the fundamental color of many Armenian rugs. Marco Polo reports the following his travel account as he passed through Cilician Armenia: "The following can be said of Turkmenia: the Turkmenian population is divided into three groups. The Turkomans are Muslims characterized by a very simple way of life and extremely crude speech. They live in the mountainous regions and raise cattle. Their horses and their outstanding mules are held in especially high regard. The other two groups, Armenians and Greeks, live in cities and forts. They make their living primarily from trade and as craftsmen. In addition to the carpets, unsurpassed and more splendrous in color than anywhere else in the world, silks in all colors are also produced there. This country, about which one might easily tell much more is subject to the Khan of the eastern Tatar Empire."[43][44]

According to the 13th-century Arab geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi, the origin of the word kali/khali/hali, a knotted carpet, is from one of the early and important Armenian carpet centers, Theodosiopolis, Karin in Armenian, Qaliqala in Arabic, modern Erzerum. He says, "А Qaliqala on fabrique des tapis qu'on nomme qali du nom abrege de la ville".[40][41] Academician Joseph Orbeli directly writes that word "karpet" is of Armenian origin.[45]

Carpet producers in Armenia

[edit]As of 2016, 5 carpet producing firms operate in the territory of Armenia:[46]

- Arm Carpet, Yerevan, since 1924 (privatized in 2002).

- Yengoyan Carpets, Karmirgyugh, Gegharkunik Province, since 1958 (privatized in 1996).

- Jrashogh Ijevan Carpets, Ijevan, Tavush Province, since 1959.

- Tufenkian Artisan Carpets (handmade carpets), Yerevan, since 1994.

- Megerian Carpets (handmade carpets), Yerevan, since 2000.

The Artsakh Carpet (handmade carpets) is operating since 2013 in Stepanakert, the capital of the self-proclaimed Republic of Artsakh.[47]

Gallery

[edit]-

Armenian girls, weaving carpets in Van, 1907, Ottoman Empire

-

Armenian carpet by ArtsakhCarpet.

-

An Armenian carpet ornament.

-

Armenian carpet with animal

-

Armenian carpet with Vishap (dragon) in Karabakh

-

Armenian carpet in Shirak

-

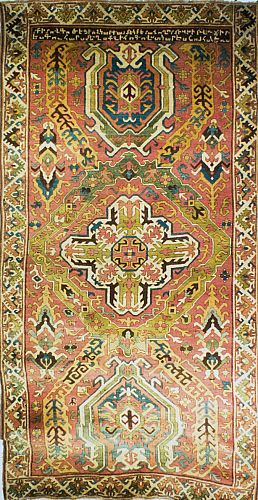

Armenian vishapagorg from Karabakh 17th-18th century

-

'Archvapar', rug as a tribute to Armenian dance

-

19 century armenian carpet form Sevan

-

Armenian carpet in Ijevan

-

Armenian carpet in Nakhichevan

-

Armenian carpets from Susa

-

Armenian shirvan

-

19 century armenian carpet from Xndzoresk, now Sunik

-

Vishapagorg 1890

-

Karabakh carpet with a testament inscription in Armenian, 1896

-

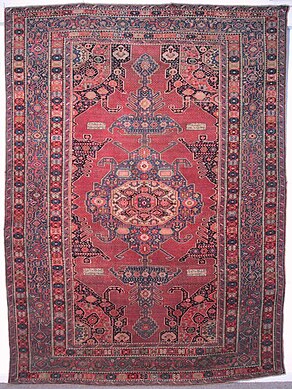

Armenian carpet in Karabakh 1900 year

-

Armenian carpet 'Mayr Hayastan' 20th century

-

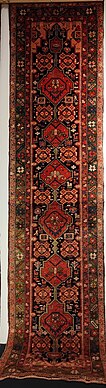

Antique armenian carpet runner Lilihan, (0.63 m x 7.35 m)

-

Armenian carpet, 14th century

-

Mosaic depicting Armenian rugs motifs in Jerusalem

-

Mosaic depicting Armenian rug motifs in 7th century Armenian church in Jerusalem

-

Ornaments on the margins of an Armenian manuscript, 1204.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Temurjyan, В. С. (1955). "The Carpet Weaving in Armenia" ("Ковроделие в Армении"). Yerevan: Institute of History, Academy of Science of the Armenian SSR.

- ^ Davtyan Давтян С., С.; АН Армянской ССР (1975). "Armenian Carpet" ("Армянский карпет"). Yerevan: Academy of Science of the Armenian SSR.

- ^ Kouymjian, Dickran; Kévorkian et B. Achdjian (1991). "Les tapis à inscriptions arméniennes",in "Tapis et textiles arméniens". Marseilles. pp. 247–253.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b N. Marr, Armgiz, 1939, Yerevan, p. 197 - in Russian

- ^ "Armenians. The End of the 19th - Beginning of the 20th century" at Russian Ethnographic Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia Archived December 24, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Армянско-русский словарь, Издательство АН Армянской ССР, Ереван, 1987, стр. 345

- ^ Армянско-русский словарь, Издательство АН Армянской ССР, Ереван, 1987, стр. 167

- ^ Armenian-English, English-Armenian Dictionary

- ^ Армянско-русский словарь, Издательство АН Армянской ССР, Ереван, 1987, стр. 337

- ^ Matthew 9:16. Ոշ ոք արկանէ կապերտ անթափ `ի վերայ հնացեակ ձորձոյ., Mark 2:21. Ոշ ոք կապերտ նոր անթափ արկանէ...etc., Hovhann Zohrapian, Scriptures of the Old and New Testments (critical edition in Armenian), Venice, 1805, pp. 654, 671.

- ^ "carpet" in "Online Etymology Dictionary", "carpet - late 13th century, "coarse cloth;" mid-14th century, "tablecloth, bedspread;" from O.Fr. carpite "heavy decorated cloth," from M.L. carpita "thick woolen cloth," pp. of L. carpere "to card, pluck," probably so called because it was made from unraveled, shreded, "plucked" fabric; from PIE *kerp- "to gather, pluck, harvest" (see harvest). Meaning shifted 15th century to floor coverings. From 16th-19th centuries often with a tinge of contempt, when used of men (e.g. carpet-knight, 1570s) by association with luxury, ladies' boudoirs, and drawing rooms. On the carpet "summoned for reprimand" is 1900, U.S. colloquial (but cf. carpet (v.) "call (someone) to be reprimanded," 1823, British servants' slang). To sweep (something) under the carpet in the figurative sense is first recorded 1963. The verb meaning "to cover with a carpet" is from the 1620s. Related: Carpeted; carpeting".

- ^ Pegoletti, La pratica della mercatura, edited by Allan Evans. Cambridge, Mass.: Mediaeval Academy of America, 1936

- ^ Голоссарий. Карпет

- ^ Kh. Hakobyan, "Medieval Art of Artsakh", Yerevan, Armenian SSR, "Parberakan, 1990, p. 84, ISBN 5-8079-0195-9

- ^ Sturtevant, Edgar H. (1931). Hittite glossary: words of known or conjectured meaning, with Sumerian ideograms and Accadian words common in Hittite texts. Language, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 3-82., Language Monograph No. 9.

- ^ James W. Redhouse, A Turkish and English Lexicon, Constantinople, 1921, p. 1423

- ^ Halil Inalcik, "Erzurum", The Encyclopedia of Islam, Leiden-London, 1965, p.712

- ^ a b Mozaffari, Ali; Barry, James (2022). "Heritage and territorial disputes in the Armenia–Azerbaijan conflict: a comparative analysis of the carpet museums of Baku and Shusha". International Journal of Heritage Studies. 28 (3): 325. doi:10.1080/13527258.2021.1993965. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30158379. S2CID 240207752.

- ^ "Armenia Textiles: An Overview". Archived from the original on 2010-01-25. Retrieved 2010-02-24. Dickran Kouymjian, "Armenia Textiles: An Overview", The catalogue of an exhibition entitled "Trames de memoire d'Armenie: broderies et tapis sur les chemins de l'exil de 1900-1940" on Armenian refugees in the textile industry in southern France after the 1915 genocide to be held at the Museon Arlaten in Arles, France from June through December 2007 as part of the Year of Armenia in France

- ^ Kouymjian, Dickran (2007). "Armenia Textiles: An Overview" в "Trames d'Arménie : tapis et broderies sur les chemins de l'exil (1900-1940)". Arles: Muséon Arlaten. Archived from the original on 2010-01-25.

- ^ Ashkhunj Poghosyan, On origin of Pazyryk rug, Yerevan, 2013 (PDF) pp. 1-21 (in Armenian), pp. 22-37 (in English)

- ^ USSR conference to exchange experiences leading restorers and researchers. The study, preservation and restoration of ethnographic objects. Theses of reports, Riga, 16–21 November 1987. pp. 17-18 (in Russian)

Л.С. Гавриленко, Р.Б. Румянцева, Д.Н. Глебовская, Применение тонкослойной хромотографии и электронной спектроскопии для анализа красителей древних тканей. Исследование, консервация и реставрация этнографических предметов. Тезисы докладов, СССР, Рига, 1987, стр. 17-18.В ковре нити темно-синего и голубого цвета окрашены индиго по карминоносным червецам, нити красного цвета - аналогичными червецами типа араратской кошенили.

- ^ Ulrich Schurmann, The Pazyryk. Its Use and Origin, Munich, 1982, p.46

- ^ a b c Volkmar Gantzhorn, "Oriental Carpets", 1998, ISBN 3-8228-0545-9

- ^ The Nine Books of the Histories of Herodotus. Thomas Gaisford, Peter Laurent, London, 1846, CLIO I p.99

- ^ a b Allen, Jim (20 March 2008). "Armenian Rugs Without Inscriptions". Archived from the original on 2 December 2009. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ Bournoutian, George A. "Armenians in Iran (ca. 1500-1994)". Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ "How a Swiss Couple Saved 8,000 Orphans during Armenian Genocide". Armenian National Committee of America. 2017-05-09. Retrieved 2024-07-10.

- ^ Vartabedian, Tom (2010-07-21). "Armenian Orphan Rug Lives up to Its Name". The Armenian Weekly. Retrieved 2024-07-10.

- ^ ""Woven Legacy: Armenian Orphan Rugs" by Hratch Kozibeyokian". Archived from the original on 2020-02-21. Retrieved 2016-01-24.

- ^ Dixon, Glenn (6 July 2018). "The Age-Old Tradition of Armenian Carpet Making Refuses to Be Swept Under the Rug". Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ Hakobyan, Hravard H (1990). The Medieval Art of Artsakh. Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Parberakan. p. 84. ISBN 5-8079-0195-9.

- ^ a b c d Hakobyan. Medieval Art of Artsakh, p. 84.

- ^ (in Armenian) Kirakos Gandzaketsi. Պատմություն Հայոց (History of Armenia). Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1961, p. 216, as cited in Hakobyan. Medieval Art of Artsakh, p. 84, note 18.

- ^ Ulubabyan, Bagrat A (1975). Խաչենի իշխանությունը, X-XVI դարերում (The Principality of Khachen, From the 10th to 16th Centuries) (in Armenian). Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Armenian Academy of Sciences. p. 267.

- ^ David Tsitsishvili "Rugs and Carpets from the Caucasus", "Avrora", Leningrad, 1984 No. 672(7-20); p.p. 7-8(total pages: 151)

- ^ Геродот, Book 1, Chapter 203, Volume 1,

- ^ "Encyclopædia Britannica: a new survey of universal knowledge, Volume 19, Author: Walter Yust, 1953, p. 623

- ^ The Silk Road represents an early phenomenon of political and cultural integration due to inter-regional trade. In its heyday, the Silk Road sustained an international culture that strung together groups as diverse as the Magyars, Armenians, and Chinese

- ^ a b А.Н Тер-Гевондян «Армения и Арабский Халифат» Издательство АН Армянской ССР, Ереван 1977 год; стр 205(всего 326)

- ^ a b Deutscher Kaliverein «Kali» p 109 Издатель Brill Archive, 1907.

- ^ М.В Бабеников «Народное декоративное искусство Закавказья и его мастера» гос.архитектуриздательство 1948 г.,173стр. стр-ца 67

- ^ Marco Polo, Il Milione, translated by Ulrich Köppens from the Ottimo-manuscript of 1309, Florence Bibliotheca Nationale, Inv. no. II.IV.88, Berlin: Propyläen, 1971

- ^ Discussion of the various manuscripts and early printed version of Marco Polo in French, Italian and German in Volkmar Ganzhorn, Der christlich orientalische Teppich, Köln: Taaschen, 1990, pp. 13-15

- ^ М.В Бабеников «Народное декоративное искусство Закавказья и его мастера», ГосАрхитектурИздательство, 1948, 173 стр., стр. 67

- ^ Armenian carpet traditions

- ^ "About Karabakh Carpet". Archived from the original on 2019-09-07. Retrieved 2016-11-19.