Archaeological Survey of India

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

Official logo of the ASI | |

| |

| Abbreviation | ASI |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1861 |

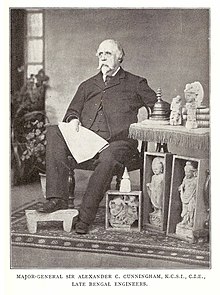

| Founder | Alexander Cunningham |

| Type | Governmental organisation |

| Headquarters | New Delhi |

Region served | India |

Official language | English Hindi |

Director General | Yadubir Singh Rawat |

Parent organisation | Ministry of Culture |

| Budget | ₹1,102.83 crore (US$130 million) (2023–24)[1] |

| Website | asi |

The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) is an Indian government agency that is responsible for archaeological research and the conservation and preservation of cultural historical monuments in the country. It was founded in 1861 by Alexander Cunningham during the British Raj who also became its first Director-General.

History

[edit]ASI was founded in 1861 by Alexander Cunningham who also became its first Director-General. The first systematic research into the subcontinent's history was conducted by the Asiatic Society, which was founded by the British Indologist Sir William Jones on 15 January 1784. Based in Calcutta, the society promoted the study of ancient Persian texts and published an annual journal titled Asiatic Researches. Notable among its early members was Charles Wilkins who published the first English translation of the Bhagavad Gita in 1785 with the patronage of the then Governor-General of Bengal, Warren Hastings.

Jones initiative resulted in the publication of Asiatick Researches, a monthly that was launched in 1788.[2] The Marquis of Wellesley's 1800 nomination of Francis Buchanan to survey Mysore was a wise move on the part of the administration at the time. He was hired in 1807 to investigate historical sites and monuments in what is now Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. The first attempt at using the legal system to force the government to become involved when there was a risk to a monument was the Bengal Regulation XIX of 1810. The publication revealed the studies and polls that the society conducted to educate the public about India's ancient treasures. Many antiques and other relics were quickly discovered during the ongoing fieldwork, and in 1814 they were placed in a museum. Subsequently, comparable organisations were founded in Madras, Chennai, in 1818, and Bombay, Mumbai, in 1804. However, the most important of the society's achievements was the decipherment of the Brahmi script by James Prinsep in 1837. This successful decipherment inaugurated the asset.

Formation of the ASI

[edit]

Armed with the knowledge of Brahmi, Alexander Cunningham, a protégé of James Prinsep, carried out a detailed survey of the Buddhist monuments of his own type to be constructed in the Nepalese tarai which lasted for over half a century. Inspired by early amateur archaeologists like the Italian military officer, Jean-Baptiste Ventura, Cunningham excavated stupas along the width, the length and breadth of India. While Cunningham funded many of his early excavations himself, in the long run, he realised the need for a permanent body to oversee archaeological excavations and the conservation of Indian monuments and used his stature and influence in India to lobby for an archaeological survey. While his attempt in 1848 did not meet with success, the Archaeological Survey of India was eventually formed in 1861 by a statute passed into law by Lord Canning with Cunningham as the first Archaeological Surveyor. The survey was suspended briefly between 1865 and 1871 due to lack of funds but restored by Lord Lawrence the then Viceroy of India. In 1871, the Survey was revived as a separate department and Cunningham was appointed as its first Director-General.[3]

1885–1901

[edit]Cunningham retired in 1885 and was succeeded as Director General by James Burgess. Burgess launched a yearly journal The Indian Antiquary (1872) and an annual epigraphical publication Epigraphia Indica (1882) as a supplement to the Indian Antiquary. The post of Director General was permanently suspended in 1889 due to a funds crunch and was not restored until 1902. In the interim period, conservation work in the different areas was carried out by the superintendents of the individual areas.

"Buck crisis" (1888–1898)

[edit]

From 1888 started severe lobbying aimed at reducing Government expenses, and at curtailing the budget of the Archaeological Survey of India, a period of about ten years known as the "Buck crisis", after the Liberal Edward Buck.[4] In effect, this severely threatened the employment of the employees of the ASI, such as Alois Anton Führer, who had just started a family and become a father.[4]

In 1892, Edward Buck announced that the Archaeological Survey of India would be shut down and all ASI staff would be dismissed by 1895, in order to generate savings for the Government's budget.[4][5] It was understood that only a fantastic archaeological discovery within the next three years for example might be able to turn public opinion and save the funding of the ASI.[4]

Great "discoveries" were indeed made with the March 1895 discovery of the Nigali Sagar inscription, which succeeded in bringing the "Buck Crisis" to an end, and the ASI was finally allowed in June 1895 to continue operations, subject to yearly approval based on successful digs every year.[7] Georg Bühler, writing in July 1895 in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, continued to advocate for the preservation of the Archaeological Survey of India, and expressed that what was needed were "new authentic documents" from the pre-Ashokan period, and they would "only be found underground".[7][8]

Another momentous discovery would be made in 1896, with the Lumbini pillar inscription, a major inscription on a pillar of Ashoka discovered by Alois Anton Führer. The inscription, together with other evidence, confirmed Lumbini as the birthplace of the Buddha.[9]

The organization was rocked when Führer was unmasked in 1898, and was found to file fraudulent reports about his investigations. Confronted by Smith about his archaeological publications and his report to the Government, Führer was obliged to admit "that every statement in it [the report] was absolutely false."[10] Under official instructions from the Government of India, Führer was relieved of his positions, his papers seized and his offices inspected by Vincent Arthur Smith on 22 September 1898.[11] Führer had written in 1897 a monograph on his discoveries in Nigali Sagar and Lumbini, Monograph on Buddha Sakyamuni's birth-place in the Nepalese tarai,[12] which was withdrawn from circulation by the Government.[6] Führer was dismissed and returned to Europe.

1901–1947

[edit]Revival under Lord Curzon

[edit]The post of Director General was restored by Viceroy and Governor-General Lord Curzon in 1902. In a speech given to the Asiatic Society on 26 February 1901, he stated that he 'regarded the conservation of ancient monuments as one of the primary obligations of Government’.[13] The Ancient Monuments Preservation Act was passed in 1904 during his tenure as viceroy.[13]

Discovery of Indus Valley Civilisation

[edit]Breaking with tradition, Curzon appointed 26-year-old Cambridge-trained archeologist John Marshall as the director-general of the ASI. Marshall had experience with archeological excavations in Greece and oversaw reforms within the organization that consolidated funding and oversight over the local branches of the ASI. He served as the director-general for a quarter of a century and during his long tenure, he replenished and invigorated the survey whose activities were fast dwindling into insignificance. Marshall established the post of Government epigraphist and encouraged epigraphical studies. In 1913, he began the excavations at Taxila, which lasted for 21 years.[14] The most significant event of his tenure was, however, the discovery of the Indus Valley civilization at Harappa and Mohenjodaro in 1921. The success and scale of the discoveries made ensured that the progress made in Marshall's tenure would remain unmatched. Marshall was succeeded by Harold Hargreaves in 1928. Hargreaves was succeeded by Daya Ram Sahni.

Sahni was succeeded by J. F. Blakiston and K. N. Dikshit both of whom had participated in the excavations at Harappa and Mohenjodaro. In 1944, a British archaeologist and army officer, Mortimer Wheeler took over as Director General. Wheeler served as Director General till 1948 and during this period he excavated the Iron Age site of Arikamedu and the Stone age sites of Brahmagiri, Chandravalli and Maski in South India. Wheeler founded the journal Ancient India in 1946 and presided over the partitioning of ASI's assets during the Partition of India and helped establish an archaeological body for the newly formed Pakistan.

1947–2019

[edit]Wheeler was succeeded by N. P. Chakravarti in 1948. The National Museum was inaugurated in New Delhi on 15 August 1949 to house the artifacts displayed at the Indian Exhibition in the United Kingdom.

Madho Sarup Vats and Amalananda Ghosh succeeded Chakravarti. Ghosh's tenure which lasted until 1968 is noted for the excavations of Indus Valley sites at Kalibangan, Lothal and Dholavira. The Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act was passed in 1958 bringing the archaeological survey under the aegis of the Ministry of Culture. Ghosh was succeeded by B. B. Lal who conducted archaeological excavations at Ayodhya to investigate whether a Ram Temple preceded the Babri Masjid. During Lal's tenure, the Antiquities and Art Treasures Act (1972) was passed recommending central protection for monuments considered to be "of national importance". Lal was succeeded by M. N. Deshpande who served from 1972 to 1978 and B. K. Thapar who served from 1978 to 1981. On Thapar's retirement in 1981, archaeologist Debala Mitra was appointed to succeed him - she was the first woman Director General of the ASI. Mitra was succeeded by M. S. Nagaraja Rao, who had been transferred from the Karnataka State Department of Archaeology. Archaeologists J. P. Joshi and M. C. Joshi succeeded Rao. M. C. Joshi was the director general when the Babri Masjid was demolished in 1992 triggering Hindu-Muslim violence all over India. As a fallout of the demolition, Joshi was dismissed in 1993 and controversially replaced as director general by Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officer Achala Moulik, a move which inaugurated a tradition of appointing bureaucrats of the IAS instead of archaeologists to head the survey. The tradition was finally brought to an end in 2010 when Gautam Sengupta an archaeologist, replaced K.M Srivastava an IAS officer as director general. He was again succeeded by Pravin Srivastava, another IAS officer. Srivastava's successor incumbent, Rakesh Tiwari was also a professional archaeologist. His successor Usha Sharma was also an IAS officer and her successor V Vidyavathi who is the present DG of ASI is also an IAS officer.

Organisation

[edit]

The Archaeological Survey of India is an attached office of the Ministry of Culture. Under the provisions of the AMASR Act of 1958, the ASI administers more than 3650 ancient monuments, archaeological sites and remains of national importance. These can include everything from temples, mosques, churches, tombs, and cemeteries to palaces, forts, step-wells, and rock-cut caves. The Survey also maintains ancient mounds and other similar sites which represent the remains of ancient habitation.[15]

The ASI is headed by a director general who is assisted by an additional director general, two joint directors general, and 17 directors.[16]

Circles

[edit]The ASI is divided into a total of 34 circles[17] each headed by a Superintending Archaeologist.[16] Each of the circles are further divided into sub-circles. The circles of the ASI are:

- Agra, Uttar Pradesh

- Aizawl, Mizoram

- Amaravati, Andhra Pradesh

- Aurangabad, Maharashtra

- Bengaluru, Karnataka

- Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh

- Bhubaneswar, Odisha

- Chandigarh

- Chennai, Tamil Nadu

- Dehradun, Uttarakhand

- Delhi

- Dharwad, Karnataka

- Goa

- Guwahati, Assam

- Hyderabad, Telangana

- Jaipur, Rajasthan

- Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh

- Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh

- Jodhpur, Rajasthan

- Kolkata, West Bengal

- Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh

- Meerut, Uttar Pradesh

- Mumbai, Maharashtra

- Nagpur, Maharashtra

- Patna, Bihar

- Raipur, Chhattisgarh

- Raiganj, West Bengal

- Rajkot, Gujarat

- Ranchi, Jharkhand

- Sarnath, Uttar Pradesh

- Shimla, Himachal Pradesh

- Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir

- Thrissur, Kerala

- Vadodara, Gujarat

The ASI also administers three "mini-circles" at Delhi, Leh and Hampi.[17]

Directors-General

[edit]The Survey has had 32 Directors-General thus far. Its founder, Alexander Cunningham served as Archaeological Surveyor between 1861 and 1865.[3]

- 1871−1885: Alexander Cunningham

- 1886−1889: James Burgess

- 1902−1928: John Marshall

- 1928−1931: Harold Hargreaves

- 1931−1935: Daya Ram Sahni

- 1935−1937: J. F. Blakiston

- 1937−1944: K. N. Dikshit

- 1944−1948: Mortimer Wheeler

- 1948−1950: N. P. Chakravarti

- 1950−1953: Madho Sarup Vats

- 1953−1968: Amalananda Ghosh

- 1968−1972: B. B. Lal

- 1972−1978: M. N. Deshpande

- 1978−1981: B. K. Thapar

- 1981−1983: Debala Mitra

- 1984−1987: M. S. Nagaraja Rao

- 1987−1989: J. P. Joshi

- 1989−1993: M. C. Joshi

- 1993−1994: Achala Moulik

- 1994−1995: S. K. Mahapatra

- 1995−1997: B. P. Singh

- 1997−1998: Ajai Shankar

- 1998−2001: S. B. Mathur

- 2001−2004: K. G. Menon

- 2004−2007: C. Babu Rajeev

- 2009−2010: K. N. Srivastava

- 2010−2013: Gautam Sengupta

- 2013−2014: Pravin Srivastava

- 2014−2017: Rakesh Tewari

- 2017−2020: Usha Sharma[18]

- 2020−2023: V.Vidyawati

- 2023−present: Yadubir Singh Rawat

Museums

[edit]India's first museum was established by the Asiatic Society in Calcutta (now Kolkata) in 1814. Much of its collection was passed on to the Indian Museum, which was established in the city in 1866.[19] The Archaeological Survey did not maintain its own museums until the tenure of its third director-general, John Marshall. He initiated the establishment of various museums at Sarnath (1904), Agra (1906), Ajmer (1908), Delhi Fort (1909), Bijapur (1912), Nalanda (1917) and Sanchi (1919). The ASI's museums are customarily located right next to the sites that their inventories are associated with "so that they may be studied amid their natural surroundings and not lose focus by being transported".

A dedicated Museums Branch was established in 1946 by Mortimer Wheeler, which now maintains a total of 50 museums spread across the country.[20]

Library

[edit]The ASI maintains a Central Archaeological Library in the Archaeological Survey of India headquarters building in Tilak Marg, Mandi House, New Delhi. Established in 1902, its collection numbers more than 100,000 books and journals. The library is also a repository of rare books, plates, and original drawings. The Survey additionally maintains a library in each of its circles to cater to local academics and researchers.[21]

Scientific Preservation

[edit]Mohammed Sanaullah Khan was appointed to the Archaeological Survey of India on 29 June 1917, marking the establishment of the Science Branch. His main responsibilities included preserving and chemically treating artefacts from museums and other artefacts. An Archaeological Chemist then oversaw the establishment of a laboratory at the Indian Museum in Calcutta, which was later moved to Dehradun in 1921–1922. The scope and activities of the Science Branch greatly expanded along with the survey's expansion and shortly after Independence. These included doing in-depth study, treating monuments, analysing material remnants, determining the reasons behind deterioration, and taking corrective action for chemical conservation.[22]

Publications

[edit]The day-to-day work of the survey was published in a series of periodical bulletins and reports. The periodicals and archaeological series published by the ASI are:

- Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum

- It consists of a series of seven volumes of inscriptions discovered and deciphered by archaeologists of the survey. Founded in 1877 by Alexander Cunningham, a final revised volume was published by E. Hultzsch in 1925.

- Annual Report on Indian Epigraphy

- The first volume of the Annual Report on Indian Epigraphy was brought out by the epigraphist -E. Hultzsch in 1887. The bulletin has not been published since 2005.

- Epigraphia Indica

- Epigraphia Indica was first published by the then Director-General, J. Burgess in 1888 as a supplementary to The Indian Antiquary. Since then, a total of 43 volumes have been published. The last volume was published in 1979. An Arabic and Persian supplement to the Epigraphia Indica was also published from 1907 to 1977.

- South Indian Inscriptions

- The first volume of South Indian Inscriptions was edited by E. Hultzsch and published in 1890. A total of 27 volumes were published till 1990. The early volumes are the main source of historical information on the Pallavas, Cholas and Chalukyas.

- Annual Report of the Archaeological Survey of India

- It was the primary bulletin of the ASI. The first annual report was published by John Marshall in 1902–03. The last volume was published in 1938–39. It was replaced by Indian Archaeology: A Review.

- Ancient India

- The first volume of Ancient India was published in 1946 and edited by Sir Mortimer Wheeler as a bi-annual and converted to an annual in 1949. The twenty-second and last volume was published in 1966.

- Indian Archaeology: A Review

- Indian Archaeology: A Review is the primary bulletin of the ASI and has been published since 1953–54. It replaced the Annual Report of the Archaeological Survey of India.

State government archaeological departments

[edit]Apart from the ASI, archaeological work in India and conservation of monuments is also carried out in some states by state government archaeological departments. Most of these bodies were set up by the various princely states before independence. When these states were annexed to India after independence, the individual archaeological departments of these states were not integrated with the ASI. Instead, they were allowed to function as independent bodies.

- Haryana State Directorate of Archaeology & Museums (formed in 1972 by upgrading the cell that was earlier under the education department)

- Orissa State Archaeology Department (1965)

- Andhra Pradesh Department of Archeology and Museums (1914)

- Karnataka State Department of Archaeology (1885)

- Kerala State Archaeology Department (formed in 1962 by merging Travancore State Archaeology Department (est 1910) and Cochin State Archaeology Department (est 1925))[23]

- Tamil Nadu Archaeology Department (1961)

- Department of Archaeology and Museum, Government of West Bengal

- Department of Archaeology, Govt. of NCT of Delhi.

Criticism

[edit]In 2013, a Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) report found that at least 92 centrally protected monuments of historical importance across the country had gone missing without a trace. The CAG could physically verify only 45% of the structures (1,655 out of 3,678). The CAG report said that the ASI did not have reliable information on the exact number of monuments under its protection. The CAG recommended that periodic inspection of each protected monument should be done by a suitably ranked officer. The Culture ministry accepted the proposal.[24] Author and IIPM Director Arindam Chaudhuri said that since the ASI is unable to protect the country's museums and monuments, they should be professionally maintained by private companies or through the public-private-partnership (PPP) model.[25]

In May 2018, the Supreme Court of India said that the ASI was not properly discharging its duty in maintaining the World Heritage Site of Taj Mahal and asked the Government of India to consider whether some other agency be given the responsibility to protect and preserve it.[26]

In popular culture

[edit]Five expert archaeologists who have also been working on Mohenjo Daro for many years—P. Ajit Prasad,[27] V. N. Prabakhar,[27] K. Krishnan,[27] Vasant Shinde,[27] and R. S. Bisht,[27] "who are all from the Archaeological Survey of India, Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda and other institutions, all with expertise in different aspects of the same civilization."[28]

See also

[edit]- State Protected Monuments of India

- List of World Heritage Sites in India

- Monuments of National Importance of India

- Delhi Archaeological Society

- Survey of India, India's central agency in charge of mapping and surveying.

- Geological Survey of India

- Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya Institute of Archaeology

- Sanskrit epigraphy

- Indian Treasure Trove Act, 1878

References

[edit]- ^ "The annual outlay for Ministry of Culture in FY 2023-24 increased by 12.97% to Rs. 3,399.65 Crore".

- ^ "History of ASI".

- ^ a b "History". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 21 April 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ a b c d Huxley, Andrew (2010). "Dr Führer's Wanderjahre: The Early Career of a Victorian Archaeologist". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 20 (4): 496–498. doi:10.1017/S1356186310000246. ISSN 1356-1863. JSTOR 40926240. S2CID 162507322.

- ^ Huxley, Andrew (2011). "Mr Houghton and Dr Führer: a scholarly vendetta and its consequences". South East Asia Research. 19 (1): 66. doi:10.5367/sear.2011.0030. ISSN 0967-828X. JSTOR 23750866. S2CID 147046097.

- ^ a b Thomas, Edward Joseph (2000). The Life of Buddha as Legend and History. Courier Corporation. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-486-41132-3. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ a b Huxley, Andrew (2010). "Dr Führer's Wanderjahre: The Early Career of a Victorian Archaeologist". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 20 (4): 499–502. doi:10.1017/S1356186310000246. ISSN 1356-1863. JSTOR 40926240. S2CID 162507322.

- ^ Bühler, G. (1895). "Some Notes on Past and Future Archœological Explorations in India". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland: 649–660. ISSN 0035-869X. JSTOR 25197280.

- ^ Weise, Kai (2013). The Sacred Garden of Lumbini: Perceptions of Buddha's birthplace. UNESCO. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-92-3-001208-3. Archived from the original on 2 June 2022. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ WILLIS, MICHAEL (2012). "Dhār, Bhoja and Sarasvatī: from Indology to Political Mythology and Back". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 22 (1): 152. ISSN 1356-1863. JSTOR 41490379.

- ^ Willis, M. (2012). "Dhar, Bhoja and Sarasvati: From Indology to Political Mythology and Back". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 22 (1): 129–53. doi:10.1017/S1356186311000794. Smith's report is given in the appendix to this article and is available here: [1] Archived 25 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Führer, Alois Anton (1897). Monograph on Buddha Sakyamuni's birth-place in the Nepalese tarai. Allahabad : Govt. Press, N.W.P. and Oudh.

- ^ a b Ghosh, Durba (March 2023). "Stabilizing History through Statues, Monuments, and Memorials in Curzon's India". The Historical Journal. 66 (2): 348–369. doi:10.1017/S0018246X22000322. ISSN 0018-246X.

- ^ "Taxila in Focus: 100 years since Marshall". stories.durham.ac.uk. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ "Monuments". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Organisation". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 28 March 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Circles". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 20 April 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ "In major bureaucratic reshuffle, 35 secretaries, additional secretaries named". livemint.com/. 22 July 2017. Archived from the original on 15 September 2017. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ "The Asiatic Society". Archived from the original on 8 April 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ "Museums". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ "Central Archaeological Library". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 14 April 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ "Scientist preservation branch of ASI".

- ^ "Kerala State Archaeology Department". keralaculture.org. Archived from the original on 13 November 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ "92 ASI-protected monuments missing". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ^ Pioneer, The. "India's monumental mess". The Pioneer. Archived from the original on 15 May 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ^ "Archaeological Survey of India failed, explore tasking Taj Mahal upkeep to another body: SC to Centre". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 10 May 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d e as officially credited in the film

- ^ Ashutosh Gowariker | Mohenjo Daro | Hrithik Roshan | Full Interview | Aamir Khan | Shah Rukh Khan. Bollywood Hungama. 4 August 2016. Archived from the original on 18 July 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2021 – via YouTube.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- World Heritage, Tentative Lists, State: India — UNESCO

- Dholavira: a Harappan City, Disstt, Kachchh, Gujarat, India, India (Asia and the Pacific), Date of Submission: 03/07/1998, Submission prepared by: Archaeological Survey of India, Coordinates: 23°53'10" N, 70°11'03" E, Ref.: 1090