Banks' Arcade

Banks' Arcade, c. 1838 (NYPL Digital b13702089) | |

| |

| General information | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 29°57′00″N 90°04′03″W / 29.95°N 90.0676°W |

| Opened | 1833 |

| Destroyed | 1851 |

| Owner | Thomas Banks |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 3 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Charles Zimpel |

Banks' Arcade was a multi-use commercial structure in New Orleans, Louisiana, United States. The building stood on the block bounded by Gravier Street, Tchoupitoulas Street, Natchez Street, and Magazine Street,[1] in the district then known as Faubourg Sainte Marie,[2] later known as the American sector and now called the Central Business District.[3] The building's central axis, originally called Banks' Alley or the Arcade Passage, is now a walk street called Arcade Place within Picayune Place Historic District.[4]

History

[edit]Banks' Arcade was constructed in 1833, by Thomas Banks, a heavily leveraged local businessman.[5] Prussian immigrant engineer and surveyor Charles Zimpel was the building's architect; he also designed the City Hotel and the Bank of Orleans.[6] The building consisted of two commercial blocks connected by a central promenade covered in a glass ceiling.[2] For many years the three-story building fronting Magazine was a landmark that served as a combination of office space, "auction-mart, [and] bar-room".[7] According to architectural historian Dell Upton, "The ground floor contained stores, John Hewlett's restaurant, and the offices of notaries, newspapers, architects, commodity brokers, auctioneers, attorneys, and slave dealers. On the second floor were offices, billiard rooms, and the Washington Guards armory, while the third floor provided 'sleeping rooms for gentlemen.'"[2] There was also a hotel within the building.[2] Banks' Arcade was one of many slave markets in New Orleans before the American Civil War.[8]

Banks was a supporter of the paramilitary action that became the Texas Revolution; two companies of soldiers known as the New Orleans Greys were recruited and organized at the Arcade's coffeehouse.[9] The coffee room was not a 19th-century café with baristas and a couple of tables, but a grand meeting room, reportedly large enough to host 5,000 people at a time.[2]

Banks ran into financial trouble during the Panic of 1837[7] and declared bankruptcy in 1842.[5] The building was heavily damaged in a fire in 1851,[10] although not wholly destroyed. There was another, minor fire at the site in 1859, at which time the "new Arcade Hotel" was under construction.[11] The surviving portion of the building was renovated after the American Civil War and about a third of original footprint survives today as the St. James Hotel.[12]

Gallery

[edit]-

Norman's plan of New Orleans & environs, 1845: Banks' Arcade is marked with number 5 in the Second Municipality

-

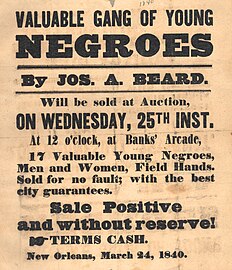

Joseph A. Beard sale advertisement broadside: "Valuable Gang of Young Negroes", 17 men and women, to be sold at auction 25 March 1840 at Banks' Arcade."

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Christovich, Mary Louise (1972). New Orleans Architecture. Vol. II: The American Sector. Pelican Publishing. p. 182. ISBN 978-1-4556-0933-8.

- ^ a b c d e Upton, Dell (2008). Another City: Urban Life and Urban Spaces in the New American Republic. Yale University Press. pp. 163–165. ISBN 9780300124880.

- ^ Campanella, Richard (2021-04-29). "Faubourg revival: This old French term was nearly extinct until it was rescued in the 1970s". Entertainment/Life. www.nola.com. Retrieved 2024-02-15.

- ^ Hawkins, Dominique M. (May 2011). "City of New Orleans HDLC: Picayune Place Historic District" (PDF). nola.gov.

- ^ a b "Houston v. City Bank of New Orleans, 47 U.S. 486 (1848)". Justia Law. Retrieved 2024-02-15.

- ^ Terrell, Ellen (2018-09-24). "Charles Zimpel: Architect, Surveyor, Businessman". Inside Adams. The Library of Congress. Retrieved 2024-02-15.

- ^ a b Chase, John Churchill (1997). Frenchmen Desire Good Children And Other Streets Of New Orleans. Simon and Schuster. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-684-84570-8.

- ^ "New Orleans, Slave Market of the South". The Historic New Orleans Collection (www.hnoc.org). Retrieved 2024-02-15.

- ^ Young, Kevin R. (2019-03-09) [1976]. "New Orleans Greys". Texas State Handbook Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2024-02-15.

- ^ Scott, Mike (2020-02-13). "It's time to remember the Alamo -- and Banks' Arcade, the New Orleans building that played a part in it". Home/Garden. www.nola.com. Retrieved 2024-02-15.

- ^ "The Arcade Buildings on Fire". The Times-Picayune. 1859-09-17. p. 1. Retrieved 2024-02-15.

- ^ Kingsley, Karen; Douglas, Lake (2019-09-16). "St. James Hotel (Banks Arcade)". ARCHIPEDIA. Society of Architectural Historians. Retrieved 2024-02-15.

External links

[edit]- "Bank's Arcade Historical Marker". www.hmdb.org.