Apennine Colossus

| Apennine Colossus | |

|---|---|

| Italian: Colosso dell'Appennino | |

Colossus of Apennine | |

| |

| Artist | Jean de Boulogne, a.k.a. Giambologna |

| Completion date | late 1580s |

| Medium | Stone |

| Dimensions | 11 meters (36 feet) |

| Location | Vaglia, Italy |

| 43°51′34.1″N 11°18′16.4″E / 43.859472°N 11.304556°E | |

The Apennine Colossus (Italian: Colosso dell'Appennino) is a stone statue, approximately 11 meters high,[1] in the estate of the Villa Demidoff in Vaglia, Tuscany, Italy. Giambologna (Flemish sculptor Jean de Boulogne) created the colossal figure, a personification of the Apennine mountains, in the late 1580´s. It was constructed on the grounds of the Villa di Pratolino, a Renaissance villa that fell into disrepair and was replaced by the Villa Demidoff in the 1800´s.[2]

Description

[edit]The colossus is about 11 metres (36 ft) high[1] and is meant as a personification of the Apennine Mountains.[3][4] It was the water source for the Pratolino,[5] its fountains and secret water plays.[6] The colossus has the appearance of an elderly man crouched at the shore of a lake[7] and is surrounded by other sculptures depicting mythological themes from Ovid's Metamorphoses including Pegasus, Parnassus or Jupiter.[8] It is presumed that Giambologna was inspired by the description of a mountain-like Atlas in Ovid's Metamorphoses, when he designed the figure of Apennine.[8] Other sources cite the Atlas as described in the Aeneid of the Roman poet Virgil as an inspiration.[9] With his left hand in front of him, the Apennine seems to squeeze the head of a sea monster[7] through whose open mouth water emanates into the pond ahead of the statue.[10] The stone colossus is depicted naked, with stalactites in the thick beard[10] and long hair to show the metamorphosis of man and mountain, blending his body with the surrounding nature, populated by aquatic vegetation.[11] The statue is described to originally have been emerging from its environment[12] like being alive. The giant was able to sweat and weep over a network of water pipes.[5] In the winter season, icicles would cover his body.[5] The work was made of stone and plaster and appearing to be partially covered with moss and lichens.[11]

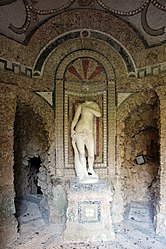

Within the giant exist a series of chambers and caves on three levels.[5] In the ground floor of the colossus exists a cave[13] containing an octagonal fountain dedicated to the Greek goddess Thetys.[14] The Italian painter Jacopo Ligozzi adorned the Grotto de Thetys[15] with frescos of villages from the Mediterranean coast of Tuscany in 1586.[16] In other chambers mining scenes based on the book De re metallica by the mineralogist Georgius Agricola were to be seen.[17] In the giant's upper floor is a chamber big enough for a small orchestra and in the head a small chamber holds a fireplace out of which the smoke would escape through his nostrils.[10] The chamber in the head had slits in the ears and the eyes.[7] Francesco I de Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, enjoyed fishing while sitting in the head chamber, throwing the fishing line through one of the eye slits.[5] At night the chamber was illuminated with torches, following which the eyes appeared to glow in the dark.[5] Initially, the back of the Colossus was protected by a structure resembling a cave, as seen on an etching by Stefano della Bella.[18][14] As Giambologna was an admirer of the Italian sculptor Michelangelo the cave-like structure was also compared with Michelangelo's style of the non-finito.[4] On top of it, there was a terrace.[5] The cave-resembling structure was demolished around 1690 by the sculptor Giovan Battista Foggini, who also built a statue of a dragon[19] to adorn the back of the colossus.[5] The dragon was described to have been a fountain, but it is assumed the dragon's belly was transformed into a fireplace while the dragon's neck and head had the function of its chimney.[20] In 1876, the Italian sculptor Rinaldo Barbetti renovated the statue.[21]

Location and ownership

[edit]The Pratolino is located about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) north of Florence at the foot of the Apennine mountain range.[22] In it, there is a rectangular square called the Prato del Appennino, situated in front of the colossus.[14]

After Francesco de' Medici's death in 1587 and that of his wife Bianca Capello the next day,[23] the villa and its surroundings fell into decay.[11] The Villa di Pratolino was demolished in 1822[11] and in 1872, the heirs of Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany, sold the estate[12] to the Demidoff family who built their own villa on it.[7] In 1981, the Villa Demidoff was purchased by the Province of Florence[24] and today the park and its giant are accessible to the public.[12]

Gallery

[edit]-

Etching by Stefano Della Bella

-

Fountain of Thetys in the ground floor by Giovanni Guerra

-

Upper chamber within the statue

-

Dragon at the back of the Colossus by Giovanni Battista Foggini

References

[edit]- ^ a b Morgan, Luke (2015), p.12

- ^ Smith, Webster (1 December 1961). "Pratolino". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 20 (4): 155–168. doi:10.2307/988039. ISSN 0037-9808. JSTOR 988039.

- ^ Morgan, Luke (2015). "The Monster in the Garden | Luke Morgan". www.upenn.edu. p. 3. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ^ a b Möseneder, Karl (1985). "Werke Michelangelos als Movens ikonographischer Erfindung". Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz. 29 (2/3): 352–353. ISSN 0342-1201. JSTOR 27653166.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Steadman, Philip (2021). "The 'garden of marvels' at Pratolino". Renaissance Fun. The machines behind the scenes. UCL Press. p. 290. doi:10.2307/j.ctv18msqmt.16. ISBN 978-1-78735-916-1. JSTOR j.ctv18msqmt.16. S2CID 241909486. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ Steadman, Philip (2021), pp. 286–287

- ^ a b c d Rubboli, Matteo (3 February 2020). "Il Colosso dell'Appennino: la Gigantesca Statua Dimenticata alle Porte di Firenze". Vanilla Magazine (in Italian). Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ a b Hunt, John Dixon (15 February 2016). Garden and Grove: The Italian Renaissance Garden in the English Imagination, 1600–1750. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-8122-9278-7.

- ^ Morgan, Luke (2015) p. 9

- ^ a b c Ilya (11 May 2013). "The Appennine Colossus". Unusual Places. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d Ricupati, Daniela (10 November 2021). "Il Colosso dell'Appennino di Giambologna". Il Giardino della Cultura (in Italian). Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ a b c "Gardens in Tuscany | Villa di Pratolino | Parco Villa Demidoff". www.travelingintuscany.com. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Steadman, Philip (2021), p. 291

- ^ a b c Smith, Webster (1961). "Pratolino". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 20 (4): 156. doi:10.2307/988039. ISSN 0037-9808. JSTOR 988039.

- ^ Tantardini, Lucia; Norris, Rebecca (2020). Lomazzo's Aesthetic Principles Reflected in the Art of his Time: With a Foreword by Paolo Roberto Ciardi, an Introduction by Jean Julia Chai, and an Afterword by Alexander Marr. Brill. p. 17. ISBN 978-90-04-43510-0.

- ^ Hirschboeck, Martin (2014). "Jacopo Ligozzi, An allegory of virtue" (PDF). p. 29. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ Steadman, Philip (2021) pp.293–294

- ^ Massar, Phyllis D. (1968). "Presenting Stefano della Bella". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 27 (3): 174. doi:10.2307/3258383. ISSN 0026-1521. JSTOR 3258383.

- ^ "Rilievo e modellazione del Gigante dell'Appennino nel parco di Pratolino | geomaticaeconservazione.it". www.geomaticaeconservazione.it. Archived from the original on 16 January 2022. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ^ Steadman, Philip (2021), pp. 290–291

- ^ "Barbetti Rinaldo". Recta Galleria d'arte – Roma (in Italian). Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Steadman, Philip (2021), p. 279

- ^ Steadman, Philip (2021), p. 315

- ^ "Russi in Italia: dizionario - Russi in Italia". www.russinitalia.it. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

External links

[edit] Media related to Appennino by Giambologna at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Appennino by Giambologna at Wikimedia Commons