Compagnie des mines d'Anzin

Fosse Saint Louis c. 1900 | |

| Industry | Coal mining |

|---|---|

| Founded | 19 November 1757 |

| Founders | Viscount Désandrouin, Prince de Croÿ, Marquis de Cernay |

| Defunct | 17 May 1946 |

| Headquarters | Anzin, Nord , France |

50°24′N 3°30′E / 50.40°N 3.50°E The Compagnie des mines d'Anzin (Anzin Mining Company) was a large French mining company in the coal basin of Nord-Pas-de-Calais in northern France. It was established in 1756 and operated for almost 200 years.

The company used innovative pumping technology to support deep mining operations in the rich bituminous coalfield. At its peak in the mid-19th century it was one of the largest industrial enterprises in France, with about 12,000 miners. Émile Zola visited the region during a strike in 1884 which he used as the basis for his novel Germinal. The work was dangerous and unhealthy, but the company paid the miners well compared to other industries, provided housing, welfare and pensions, and sponsored social activities. The mines reached their peak of prosperity before World War I (1914–18), but were badly damaged during the war. They struggled to regain profitability in period leading up to World War II (1939–45). The mines were nationalized in 1946. Many were closed in the 1970s and 1980s. The last ceased operation in 1990. The landscape has been partly restored but traces of mining such as slag heaps, ponds and railway cuttings remain, and a few heritage sites have been preserved.

Location

[edit]

The Nord-Pas de Calais Mining Basin extends for 100 kilometres (62 mi) from the Valenciennes region in the east past Douai and Lens to Béthune in the west. It is 4 to 12 kilometres (2.5 to 7.5 mi) wide. For many years it was the most important coalfield in France. Over two billion tons of coal were extracted from the basin between the early 18th century and late 20th century. The concessions granted to the Compagnie des mines d'Anzin lay in the east of this basin, named after the town of Anzin, to the north of Valenciennes.[1]

Early years

[edit]

Coal was mined in the pre-industrial era for use by blacksmiths, but was seen as an inferior fuel to wood for heating a home. Demand began to rise in the early 18th century due to population growth and limited wood supplies.[1] The Mons-Charleroi coal basin was lost to France in 1713 by the Treaty of Utrecht.[2] The Viscount Jean-Jacques Desandrouin (1681–1761) bailli of Charleroi, had made a fortune at his seignurie of Lodelinsart from a coal mine, forges and glassworks. In 1716 he began to explore the region of French Hainaut in the hope of finding a westward extension of the Mons-Charleroi deposit. In 1720 Désandrouin and his research director Jacques Mathieu, with a team of twenty miners, found coal at Fresnes-sur-Escaut.[2] The government gave Desandrouin a 20-year exclusive mining privilege and a subsidy of 35,000 livres. He struggled on with many setbacks and great loss of money, and finally found bituminous coal at the village of Anzin in 1734, when he was on the verge of ruin. By 1756 his company had 1,500 workers and sixteen pits.[3]

When he learned of the discovery the Prince de Croÿ, lord of Valenciennes, asserted his rights to the deposit and a prolonged legal battle began. On 14 January 1744 the king decreed that all minerals below the soil were the property of the crown, and could only be exploited by the landowner after a formal concession had been granted. Eventually in 1757 the Viscount Désandrouin, Prince de Croÿ, Marquis de Cernay and others founded the first mining company in the Nord, the Compagnie des Mines d'Anzin.[1] The company was formally created by the merger on 19 November 1757 of the Société Desandrouin-Taffin, the Société Desandrouin-Cordier and the Société de Cernay.[4] Desandrouin received twelve shares of the new company, Cernay eight and Croy four.[5] It was one of the first large industrial companies in France.[6]

The total concession area of 28,000 hectares (69,000 acres) was the largest in the Nord-Pas de Calais Basin.[7] The company introduced steam engines to operate pumps that removed water from the mines, which could reach a depth of 200 metres (660 ft).[8] In 1789 the company had 25 mine shafts, 12 steam engines and 4,000 miners, and produced one third of French coal.[9]

Most of the workers were recruited locally and some were highly skilled. Typically they worked in family teams, a practice encouraged by the company, and were paid by performance. To retain workers the company supported families after death or disability, and provided health services and pensions.[1] A mine worker might start as a child of seven, dragging wagons of coal, then graduate to working on the coal face. Typically the miner worked lying on his side since the veins of coal were rarely more than 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) thick. After the age of 35 they would be given less demanding work in the mine or on the surface. The mines were worked around the clock, on three shifts. Sometimes explosives were used to open new galleries. The work was dangerous and unhealthy, but was well-paid.[1]

Revolutionary period

[edit]The French Revolution caused the status of the company to be questioned. The company employed Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau in 1791 to defend its interests, and then Jean Jacques Régis de Cambacérès as legal counsel.[9] Between 1792 and 1794 the mines were badly damaged during fighting between the French revolutionary forces and the monarchist Allies.[10] The assets of the emigrant nobles were sold to Stanislaus Désandrouin in June 1795. A month later he resold a large share to a group of financiers from the French East India Company.[9] The pits were repaired and production expanded again, with a new shaft sunk in early 1796. Production rose to 248,000 tons in 1799, and by 1800 the company had almost completely recovered.[11]

Claude Périer (1742–1802) obtained 27.5 deniers of the Anzin Mining Company during this financial reorganization.[12] In addition to Désandrouin the new owners included the leading members of the East India Company including Pierre Desprez, Jean-Barthélémy Le Couteulx de Canteleu, Augustin-Jacques Perier, Guillaume Sabatier, the widows of the directors Pierre Bernier and Pourrat, Thieffries (the partner of Périer) and smaller shares held by the two legal advisers of the company, Berryer and Cambacérès. With the financial support of Sabatier the Périers gradually took control of the Mines d'Anzin.[9] When Claude Périer died in 1801 his shares were divided between his eight sons and two daughters. In 1805 Scipion Périer became director of the mining company, and Casimir Pierre Périer became assistant director.[12] The Périers held a large block of shares in the company, and their bank managed the company's finances, including investments, changes in shareholdings and loans to shareholders. The machine shops of Jacques-Constantin Périer at Chaillot supplied steam engines and equipment for mining from 1818.[12]

First Empire and Bourbon restoration

[edit]

The company was the first to build housing for miners in 1810 near Valenciennes. There are still 79 settlements founded by the company including villages, towns and garden cities. The company generally only provided housing, and did not introduce community facilities in these settlements.[7] From 1820 there were increasing numbers of exploratory mines throughout the concession area. The pits sunk at Abscon in 1823 and 1824 were disappointing. The company decided to exploit the promising deposits in the Denain area more intensively, and opened multiple mines in this area between 1826 and 1831 including Villars, Turenne, Bayard and la Pensée.[13]

When Scipion Périer died in 1821, Casimir Périer became director of the Anzin mines and Joseph Périer became assistant director.[12] In 1823 Casimir Périer replaced his brother Scipion as head of the company, and initiated a thorough reorganization to improve profitability. Wages were reduced, older workers retired, and modern equipment installed.[1] In 1831 King Louis Philippe named Casimir Périer president of the council and Minister of the Interior.[14] From the time of the Revolution until 1833 there was only one short and partial strike in 1824.[15]

Joseph Périer was concerned that productivity might suffer if the mines supervisory staff became too close to the workers. In 1826 he asked the general agent of the Anzin company "to arrange a kind of police that would inform him if the director, the under-director and the master foremen were doing their job."[16] Joseph Périer became director after Casimir died in 1832, and Casimir's son Auguste became assistant director.[12] 4,000 miners went on strike in May 1833, and almost all the pits were closed by shutting down the pumps. The miners held out for eight days against the management, authorities and 5,000 troops who were brought in to "restore order". The strike then collapsed. A few of the leaders were tried and let off with light punishments. The cause is obscure but may have been due to general dissatisfaction with Perier's efficiency measures.[15][17]

The company was quick to exploit steam-powered railways, and in 1834 built a line for coal trucks between Saint-Waast and Denain.[13] The Somain-Péruwelz Railway, built by the Compagnie des mines d'Anzin, was one of the first passenger railways in France. The concession was granted on 24 October 1835 and work started immediately.[18] On 21 October 1838 the "Train d'Anzin" opened to passenger traffic. It was not until 1846 that the official railway line reached the region, making Saint-Waast the first railway station in the Nord. The line was soon extended to Abscon.[13] The census of 1842 shows that Joseph Périer may have been the most wealthy property-owner in France, paying 56,503 francs, mostly for the Anzin mines.[19]

The Renard (Fox) pit was opened in 1836, later to be the subject of Émile Zola's novel Germinal. The dialect poet Mousseron ("Cafougnette") worked there for 46 years.[13] The Joseph Périer mine was opened in 1841, and reached coal at 75 metres (246 ft). By 1867 it had reached a depth of 380 metres (1,250 ft).[20] Pits proliferated in the Valenciennes region at Saint-Waast (Réussite, Régie), Anzin (St Louis) and Escaudain (St Mark). The company was the largest coal producer in France, but soon faced competition from companies operating nearby, notable the Aniche company to the west of the concession.[13] The main shareholders and executives included leading French businessmen and politicians such as such as Adolphe Thiers (1797–1877).[21] The wife of Auguste Casimir-Perier (1811–76), a member of the board, was sister of the wife of Gaston Audiffret-Pasquier (1823–1905) who also sat on the board. Audiffret-Pasquier was an Orleanist leader, president of the national assembly and then of the senate.[22]

Second Empire and 3rd Republic

[edit]

During the Second French Empire (1852–70) companies exploiting the deposits of the Pas-de-Calais to the west began to increase output. In 1878 Pas-de-Calais produced more coal than Nord. By 1890 the Société des mines de Lens had become the largest mining company in France, displacing Anzin. Technology had changed little since the 18th century, with coal still extracted manually, but towards the end of the century laws were implemented to reduce child labor.[1][a] The mining company was paternalistic, providing housing, clinics, schools, canteens and shops, paying relief and pensions, and sponsoring sports and social activities. There were improvements to workers' rights, with strikes allowed from 1864 and trade unions from 1884.[1]

Émile Zola visited the area in 1884 to obtain background for his novel Germinal. He arrived at the time of a strike by 12,000 miners.[23] The strike began at Anzin in February 1884 after 140 workers, mostly union members, were dismissed. The company called in troops to defend the mines, and refused to make any concessions. The strike lasted 56 days, and was headline news in France, but failed completely.[1] During this strike Émile Basly emerged as a leader of the miners. He became secretary general of the Nord miners' union, president of the Pas-de-Calais miners' union, deputy and mayor of Lens.[21] A strike began in Marles-les-Mines in the winter of 1891 and spread throughout the region, mainly for higher wages. The outcome was the first collective labor agreement in France, the Convention of Arras, which established insurance funds and pensions. Women were banned from underground work in 1892, and boys under twelve in 1906. In 1910 the working day was set at eight hours, with a mandatory day off each week.[1]

During World War I (1914–18) the front lines ran across the mining area, and many of the mines were systematically destroyed by the Germans. After the war the mines were reopened. An influx of Polish miners made up for the huge casualties among French miners during the war. During the depression of the 1930s many of these workers and their families were forcibly returned to Poland. The communists and socialists struggled for control of the mining region. During World War II (1939–45) the mines were occupied by the Germans in 1940 and ruthlessly exploited using laborers from Ukraine, Russia, Serbia and elsewhere.[1]

Nationalization and closure

[edit]A decree of 13 December 1944 created the state-owned Houillères Nationales to acquire the privately held mining properties. Shareholders of the former companies received compensation of 8 francs per ton, higher than the profit per ton they had made in 1938. The state assigned managers to the new company and set wages and prices, but the company otherwise operated independently.[7] The law of 17 May 1946 created the Charbonnages de France, completing the transfer to the state. An administrative council represented workers, consumers and the state.[7]

Over the years that followed there were various administrative changes. Efforts were made to restore the landscape as pits were closed, and a government program was launched in the late 1970s to clean up the main urban centers. There were accelerated pit closures during the 1980s. The last pit in the Nord-Pas de Calais region closed in October 1990. The old railways have been converted to walking and hiking routes, and ponds converted for recreational use or made into ecological reserves. A few sites have been preserved as mining heritage sites for tourists.[7]

-

Villars in Denain c. 1900

-

Roeulx in Escaudain c. 1900

-

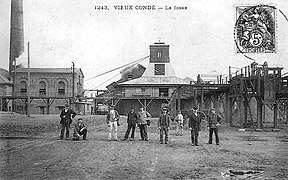

Vieux-Condé start of 20th century

-

Haveluy 1900

-

Blignières in Wavrechain c. 1920

-

Réussite c. 1920

-

Bleuse-Borne in Anzin 1920

-

Lambrecht 1949

-

Thiers in Bruay c. 1950

-

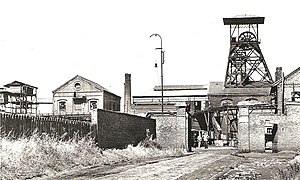

Saint Mark in 1960

Notes

[edit]- ^ The work was still unhealthy. An 1878 book was devoted to the study of miners' anemia, called "Anzin anemia".(Manouvriez 1878, p. 3)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Les trois âges de la mine 2002.

- ^ a b Geiger 1974, p. 16.

- ^ Geiger 1974, p. 17.

- ^ Grar 1848, p. 110.

- ^ Geiger 1974, p. 20.

- ^ Compagnie des Mines d’Anzin ... Archives, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e Histoire du Bassin minier – Atlas du Patromoine.

- ^ Michel 1969.

- ^ a b c d Prunaux 2006.

- ^ Geiger 1974, p. 23.

- ^ Geiger 1974, p. 29.

- ^ a b c d e Barker 1961, p. 167.

- ^ a b c d e Dussart 2006.

- ^ Jolly 1960–1977.

- ^ a b Geiger 1974, p. 46.

- ^ Reid 1985, pp. 593–594.

- ^ Hardy-Hémery 2005.

- ^ Statistique archéologique du Département du Nord, p. 391.

- ^ Tudesq 1961, p. 342.

- ^ Dormoy 1867, p. 230.

- ^ a b Leroy 2002.

- ^ Mayeur, Corbin & Schweitz 1995, p. 203.

- ^ Mitterrand 2002, pp. 37ff.

Sources

[edit]- Barker, Richard J. (June 1961), "French Entrepreneurship During the Restoration: The Record of a Single Firm, the Anzin Mining Company", The Journal of Economic History, 21 (2), Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Economic History Association: 161–178, doi:10.1017/S0022050700101949, JSTOR 2115186

- "Compagnie des Mines d'Anzin" (PDF). Archives Nationales du Monde du Travail (in French). Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- Dormoy, Émile (1867), Topographie souterraine du bassin houiller de Valenciennes (in French), Imprimerie impériale, retrieved 2017-08-30

- Dussart, Michel (2006-12-08). "La compagnie des mines d'Anzin" (in French). Diocèse de Cambrai. Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- Geiger, Reed G. (1974), Anzin Coal Company, 1800-1833: Big Business in the Early Stages of the French Industrial Revolution, University of Delaware Press, ISBN 978-0-87413-108-6, retrieved 2015-12-14

- Grar, Édouard (1848), Histoire de la recherche, de la découverte et de l'exploitation de la houille dans le Hainaut français, dans la Flandre française et dans l'Artois, 1716-1791 (PDF) (in French), vol. II, Valenciennes: Impr. de A. Prignet

- Hardy-Hémery, Odette (2005). "Diana Cooper-Richet, Le peuple de la nuit. Mines et mineurs en France (XIXe-XXe siècle), Paris, Perrin, 2002, 441 p., 22 €". Revue d'histoire moderne et contemporaine (in French). 52 (4). Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- "Histoire du Bassin minier". Atlas du Patromoine (in French). Archived from the original on 2015-12-07. Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- Jolly, Jean (1960–1977). "Jean, Paul, Pierre PERIER DIT CASIMIR-PERIER". Dictionnaire des parlementaires français; notices biographiques sur les ministres, députés et sénateurs français de 1889 à 1940 (in French). Paris: Presses universitaires de France. ISBN 2-1100-1998-0. Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- Leroy, Jean-François (2002-02-08). "Émile Basly". Nordmag (in French). Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- "Les trois âges de la mine". Bulletin de Liaison des Professeurs d'Histoire-Géographie de l'Académie de Reims (in French) (27). 2002. Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- Manouvriez, Anatole (1878), De l'anémie des mineurs, dite d'Anzin, Giard

- Mayeur, Jean Marie; Corbin, Alain; Schweitz, Arlette (1995-01-01), Les immortels du Sénat, 1875-1918: les cent seize inamovibles de la Troisième République, Publications de la Sorbonne, ISBN 978-2-85944-273-6, retrieved 2015-12-13

- Michel, Joël (1969), "La découverte du charbon dans le valenciennois", La Magazine du Mineur (in French), ORTF, retrieved 2015-12-13

- Mitterrand, Henri (2002), "Zola à Anzin : les mineurs de Germinal", Travailler (in French), 1 (7): 37, doi:10.3917/trav.007.0037

- Prunaux, Emmanuel (2006-08-19). "La Société des Mines d'Anzin". Cambacérès (in French). Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- Reid, Donald (October 1985), "Industrial Paternalism: Discourse and Practice in Nineteenth-Century French Mining and Metallurgy", Comparative Studies in Society and History, 27 (4), Cambridge University Press: 579–607, doi:10.1017/S0010417500011671, JSTOR 178593

- Statistique archéologique du Département du Nord - seconde partie (in French). Librairie Quarré et Leleu à Lille, A. Durand 7 rue Cujas à Paris. 1867.

- Tudesq, A.-J. (1961), "La Banque de France au milieu du XIX e siècle. Étude des structures sociales", Revue Historique (in French), 226 (2), Presses Universitaires de France: 339–356, JSTOR 40949498