Antonine Itinerary

The Antonine Itinerary (Latin: Itinerarium Antonini Augusti, "Itinerary of the Emperor Antoninus") is an itinerarium, a register of the stations and distances along various roads. Seemingly based on official documents, possibly in part from a survey carried out under Augustus, it describes the roads of the Roman Empire.[1] Owing to the scarcity of other extant records of this type, it is a valuable historical record.[2]

Almost nothing is known of its author or the conditions of its compilation. Numerous manuscripts survive, the eight oldest dating to some point between the 7th to 10th centuries after the onset of the Carolingian Renaissance.[3] Despite the title seeming to ascribe the work to the patronage of the 2nd-century Antoninus Pius, all surviving editions seem to trace to an original towards the end of the reign of Diocletian in the early 4th century.[3] The most likely imperial patron—if the work had one—would have been Caracalla.[1]

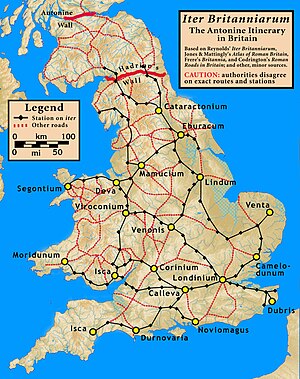

Iter Britanniarum

[edit]The British section is known as the Iter Britanniarum, and can be described as the 'road map' of Roman Britain. There are 15 such itineraries in the document applying to different geographic areas.

The itinerary measures distances in Roman miles, where 1,000 Roman paces equals one Roman mile. A Roman pace was two steps, left plus right, and was conventionally set at 5 Roman feet (0.296m), resulting in a Roman mile of approximately 1,480 metres (0.92 miles).

Examples

[edit]Below are the original Latin ablative forms for sites along route 13,[4] followed by a translation with a possible (but not necessarily authoritative) name for the modern sites.[5] A transcriber omitted an entry, so that the total number of paces did not equal the sum of paces between locations.

| Latin ablative | Translated possible site name | Distance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roman (mile) | Metric (km) | English (mile) | ||

| Item ab Isca Calleva mpm[6] cviiii[7] sic | A route from Isca Silurum to Calleva Atrebatum thus | 109 | 161 | 100 |

| Burrio mpm viii | Usk, Monmouthshire | 8 | 12 | 7.5 |

| Blestio mpm xi | Monmouth, Monmouthshire | 11 | 16 | 10 |

| Ariconio mpm xi | Bury Hill, Weston under Penyard, Herefordshire | 11 | 16 | 10 |

| Clevo mpm xv | Gloucester, Gloucestershire | 15 | 22 | 14 |

| (no entry - mpm xx) | perhaps Corinium Dobunnorum at modern Cirencester, Gloucestershire | (20) | (30) | (18.5) |

| Durocornovio mpm xiiii | perhaps Wanborough, Wiltshire | 14 | 21 | 13 |

| Spinis mpm xv | Speen, Berkshire | 15 | 22 | 14 |

| Calleva mpm xv | Silchester, Hampshire | 15 | 22 | 14 |

Below are the original Latin names for sites along route 14,[8] followed by a translation with a possible (but not necessarily authoritative) name for the modern sites.[5]

| Latin ablative | Translated possible site name | Distance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roman (mile) | Metric (km) | English (mile) | ||

| Item alio itinere ab Isca Calleva mpm ciii sic | An alternate route from Isca Silurum to Calleva Atrebatum thus | 103 | 152 | 95 |

| Venta Silurum mpm viiii | Caerwent, Monmouthshire | 9 | 13 | 8 |

| Abone mpm xiiii | Sea Mills, Gloucestershire | 14 | 21 | 13 |

| Traiectus mpm viiii | perhaps Bitton, near Willsbridge, Gloucestershire | 9 | 13 | 8 |

| Aquis Solis mpm vi | Bath, Somerset | 6 | 9 | 5.5 |

| Verlucione mpm xv | Sandy Lane, Wiltshire | 15 | 22 | 14 |

| Cunetione mpm xx | Mildenhall, Wiltshire | 20 | 30 | 18.5 |

| Spinis mpm xv | Speen, Berkshire | 15 | 22 | 14 |

| Calleva mpm xv | Silchester, Hampshire | 15 | 22 | 14 |

A confounding factor

[edit]De Situ Britanniae (made available c. 1749, published 1757) was a forgery by Charles Bertram that provided much spurious information on Roman Britain, including "itineraries" that overlapped the legitimate Antonine Itineraries, sometimes with contradicting information. Its authenticity was not seriously challenged until 1845, and it was still cited as an authoritative source until the late nineteenth century. By then, its false data had infected almost every account of ancient British history, and had been adopted into the Ordnance Survey maps,[9] as General Roy and his successors believed it to be a legitimate source of information, on a par with the Antonine Itineraries. While the document is no longer cited since its authenticity became indefensible, its data has not been systematically removed from past and present works.

Some authors, such as Thomas Reynolds, without challenging the authenticity of the forgery, took care to note its discrepancies and challenge the quality of its information.[10][11] This was not always so, even after the forgery was debunked.

Gonzalo Arias (died 2008) proposed that some of the distance anomalies in the British section of the Antonine Itinerary resulted from the loss of Latin grammatical endings, as these had marked junctions heading towards places, as distinct from the places themselves.[12] However, Arias may not have taken account of earlier work indicating that distances were measured between the edges of administrative areas of named settlements as opposed to centre-to-centre, thereby explaining supposed distance shortfalls and providing additional useful data on the approximate sizes of such areas.[13]

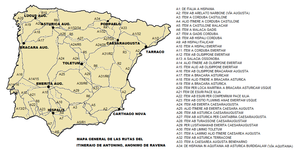

Hispania

[edit]

There are 34 routes in the itinerary for the provinces of Hispania.

| Route | Start | End | Distance (Roman miles) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mediolanum (Milan) | Legio VII Gemina (León) | 1257 |

| 2 | Arelate (Arles) | Castulo | 898 |

| 3 | Corduba (Córdoba) | Castulo | 99 |

| 4 | Corduba | Castulo | 78 |

| 5 | Castulo | Malaca (Málaga) | 291 |

| 6 | Malaca | Gades (Cádiz) | 145 |

| 7 | Gades | Corduba | 294 |

| 8 | Hispalis (Seville) | Corduba | 94 |

| 9 | Hispalis | Italica | 6 |

| 10 | Hispalis | Emerita (Mérida) | 162 |

| 11 | Corduba | Emerita | 144 |

| 12 | Olisipo (Lisbon) | Emerita | 161 |

| 13 | Salacia (Alcácer) | Ossonoba (Faro) | 16 |

| 14 | Olisipo | Emerita | 145 |

| 15 | Olisipo | Emerita | 220 |

| 16 | Olisipo | Bracara (Braga) | 244 |

| 17 | Bracara | Asturica (Astorga) | 247 |

| 18 | Bracara | Asturica | 215 |

| 19 | Bracara | Asturica | 299 |

| 20 | Bracara | Asturica | 207 |

| 21 | Esuris (Castro Marim) | Pax Julia | 267 |

| 22 | Esuris | Pax Julia | 76 |

| 23 | Mouth of the Ana (Guadiana) | Emerita | 313 |

| 24 | Emerita | Caesaraugusta (Zaragoza) | 632 |

| 25 | Emerita | Caesaraugusta | 348 |

| 26 | Asturica | Caesaraugusta | 497 |

| 27 | Asturica | Caesaraugusta | 301 |

| 28 | Turiaso (Tarazona) | Caesaraugusta | 56 |

| 29 | Emerita | Caesaraugusta | 458 |

| 30 | Laminium (Fuenllana) | Toletum (Toledo) | 95 |

| 31 | Laminium | Toletum | 249 |

| 32 | Asturica | Tarraco (Tarragona) | 482 |

| 33 | Caesaraugusta | Benearnum (Lescar) | 112 |

| 34 | Asturica | Burdigala (Bordeaux) | 421 |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Antonini Itinerarium". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 148.

- ^ Rivet, A. L. F.; Jackson, Kenneth (1970). "The British Section of the Antonine Itinerary". Britannia. 1: 34–82. doi:10.2307/525833. JSTOR 525833. S2CID 162217811.

- ^ a b Öberg (2023), p. 5.

- ^ Parthey & Pinder 1848:232–33 in Britannia

- ^ a b Codrington 1918, In Roman Roads in Britain

- ^ = milia plus minus

- ^ Roman numerals

- ^ Parthey & Pinder 1848:233 in Britannia

- ^ Redmonds, George (2004), Names and History: People, Places and Things, Hambledon & London, pp. 65–68, ISBN 978-1-85285-426-3 A Major Place-Name Ignored

- ^ Reynolds 1799 Iter Britanniarum

- ^ Dyer 1816 Vulgar Errors, Ancient and Modern

- ^ For most Roman roads in Hispania, see Gonzalo Arias. "El Miliario Extravagante". Archived from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2012-08-27.. Cf. also his Grammar in the Antonine Itinerary: A Challenge to British Archaeologists (available in only a few libraries).

- ^ Cf. Rodwell, "Milestones, Civic Territories and the Antonine Itinerary", 6 Britannia 76–101 (1975).

Bibliography

[edit]- The standard modern edition of the Itinerary is in O. Cuntz, Itineraria Romana, vol. 1: Itineraria Antonini Augusti et Burdigalense (Leipzig 1929), nos, 1 – 75 (terrestrial), 76 – 85 (maritime).

- The first edition was by Geoffroy Troy: Torinus, Godofredus, ed. (1512), Itinerarivm prouinciarum omniu[m] Antonini Augusti : cum fragmento eiusdem necnon indice haud quaq[ue] asperna[n]do, Paris: Henricus Stephanus, OCLC 807069197

- Bernd Löhberg, Das 'Itinerarium provinciarum Antonini Augusti' (2006)

- Codrington, Thomas (1918), Roman Roads in Britain (Third ed.), London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (published 1919)

- Dyer, Gilbert (1816), Vulgar Errors, Ancient and Modern, Gilbert Dyer

- Öberg, Tomas (2023), The Accuracy of Road Distances in the Antonine Itinerary, Lund: Lund University.

- Parthey, Gustav; Pinder, Moritz, eds. (1848), Itinerarium Antonini Augusti et Hierosolymitanum, Berlin

- Reynolds, Thomas (1799), Iter Britanniarum, Cambridge