1984 anti-Sikh riots

| 1984 anti-Sikh riots | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Insurgency in Punjab, India | |||

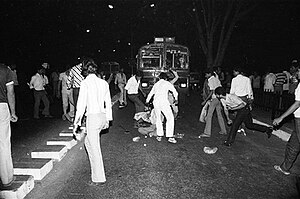

Sikh man surrounded and beaten by a mob | |||

| Date | 31 October – 3 November 1984 | ||

| Location | 30°46′N 75°28′E / 30.77°N 75.47°E | ||

| Caused by | Assassination of Indira Gandhi | ||

| Goals | |||

| Methods | Pogrom,[2] mass murder, mass rape, arson, plundering,[1] acid throwing,[3] immolation[4] | ||

| Parties | |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 3,350 (Indian government figure)[7][8] 8,000–17,000 Sikhs (other estimates)[dubious – discuss][4][9] | ||

The 1984 anti-Sikh riots, also known as the 1984 Sikh massacre, was a series of organised pogroms against Sikhs in India following the assassination of Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards.[10][11][12][13][5][14] Government estimates project that about 2,800 Sikhs were killed in Delhi[5][6] and 3,350 nationwide,[7][8] whilst other sources estimate the number of deaths at about 8,000–17,000.[dubious – discuss][4][9][15][16]

The assassination of Indira Gandhi itself had taken place after she had ordered Operation Blue Star, a military action to secure the Golden Temple, a Sikh temple complex in Amritsar, Punjab, in June 1984.[17] The operation had resulted in a deadly battle with armed Sikh groups who were demanding greater rights and autonomy for Punjab and the deaths of many pilgrims. Sikhs worldwide had criticized the army action and many saw it as an assault on their religion and identity.[18][19][20]

In the aftermath of the pogroms, the government reported that 20,000 had fled the city; the People's Union for Civil Liberties reported "at least" 1,000 displaced persons.[21] The most-affected regions were the Sikh neighborhoods of Delhi. Human rights organizations and newspapers across India believed that the massacre was organized.[5][22][23] The collusion of political officials connected to the Indian National Congress in the violence and judicial failure to penalize the perpetrators alienated Sikhs and increased support for the Khalistan movement.[24] The Akal Takht, Sikhism's governing body, considers the killings a genocide.[25][26][27]

In 2011, Human Rights Watch reported that the Government of India had "yet to prosecute those responsible for the mass killings".[28] According to the 2011 WikiLeaks cable leaks, the United States was convinced of the Indian National Congress's complicity in the riots and called it "opportunism" and "hatred" by the Congress government, of Sikhs.[29] Although the U.S. has not identified the riots as genocide, it acknowledged that "grave human rights violations" occurred.[30] In 2011, the burned sites of multiple Sikh killings from 1984, were discovered in Hondh-Chillar and Pataudi areas of Haryana.[31] The Central Bureau of Investigation believes that the violence was organised with support from the Delhi police and some central-government officials.[22]

After 34 years of delay, in December 2018, the first high-profile conviction for the 1984 anti-Sikh riots took place with the arrest of Congress leader Sajjan Kumar, who was sentenced to life imprisonment by the Delhi High Court.[32] Very few convictions have taken place in the pending 1984 cases, with only one death penalty conviction for an accused, Yashpal in the case of murdering Sikhs in the Mahipalpur area of Delhi.[33][34][35]

Background

In the 1972 Punjab state elections, Congress won and Akali Dal was defeated. In 1973, Akali Dal put forward the Anandpur Sahib Resolution to demand more autonomy to Punjab.[36] It demanded that power be generally devolved from the Central to state governments.[37] The Congress government considered the resolution a secessionist document and rejected it.[38] Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, a prominent Sikh leader of Damdami Taksal, then joined the Akali Dal to launch the Dharam Yudh Morcha in 1982 to implement the Anandpur Sahib resolution. Bhindranwale had risen to prominence in the Sikh political circle with his policy of getting the Anandpur Resolution passed.[39] Others demanded an autonomous state in India, based on the Anandpur Sahib Resolution.

As high-handed police methods were used on protesters during the Dharam Yudh Morcha, creating state repression affecting a very large segment of Punjab's population, retaliatory violence came from a section of the Sikh population, widening the scope of the conflict by the use of violence of the state on its own people, creating fresh motives for Sikh youth to turn to insurgency.[40]: 32–33 The concept of a separate Sikh state (the Khalistan movement) was still vague even while the complex was fortified under the influence of former Sikh army officials alienated by government actions who now advised Bhindranwale, Major General Shabeg Singh and retired Major General and Brigadier Mohinder Singh, and at that point the concept was still not directly connected with the movement he headed.[41] In other parts of Punjab, a "state of chaos and repressive police methods" combined to create "a mood of overwhelming anger and resentment in the Sikh masses against the authorities," making Bhindranwale even more popular, and demands of independence gain currency, even amongst moderates and Sikh intellectuals.[41]

By 1983, the situation in Punjab was volatile. In October, Sikh militants stopped a bus and shot six Hindu passengers. On the same day, another group killed two officials on a train.[42]: 174 The Congress-led central government dismissed the Punjab state government (led by their party), invoking the president's rule. During the five months before Operation Blue Star, from 1 January to 3 June 1984, 298 people were killed in violent incidents across Punjab. In the five days preceding the operation, 48 people were killed by violence.[42]: 175 According to government estimates, the number of civilians, police, and militants killed was 27 in 1981, 22 in 1982, and 99 in 1983.[43] By June 1984, the total number of deaths was 410 in violent incidents and riots while 1,180 people were injured.[44]

On 1 June, Operation Blue Star was launched to remove Bhindranwale and armed militants from the Golden Temple complex.[45] On 6 June Bhindranwale died in the operation. Casualty figures for the Army were 83 dead and 249 injured.[46] According to the official estimate presented by the Indian government, 1592 were apprehended and there were 493 combined militant and civilian casualties.[47] Later operations by Indian paramilitary forces were conducted to clear the separatists from the state of Punjab.[48]

The operation carried out in the temple caused outrage among the Sikhs and increased the support for Sikh separatism.[37] Four months after the operation, on 31 October 1984, Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her two Sikh bodyguards, Satwant Singh and Beant Singh.[49] One of the assassins was fatally shot by Gandhi's other bodyguards while the other was convicted of Gandhi's murder and then executed. Public outcry over Gandhi's death led to the killings of Sikhs in the ensuing 1984 anti-Sikh riots.[50][51]

Geo-political context

Before British colonisation, Punjab was a region dominated by Sikh states known as Misls, which were later unified into the Sikh Empire by Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Following the Second Anglo-Sikh War in 1849, the Sikh Empire was dissolved, leading to its integration into the British province of Punjab. This period saw the emergence of religio-nationalist movements as a response to British administrative policies and socio-political changes. The concept of a Sikh homeland, Khalistan, emerged in the 1930s as the British Empire began to dissolve. This idea gained momentum in response to the Muslim League's demand for a Muslim state, with the Sikhs viewing it as an encroachment on historically Sikh territory. The Akali Dal, a Sikh political party, envisioned Khalistan as a theocratic state, comprising parts of what is today Punjab in both India and Pakistan.

Post-independence, the Akali Dal led the Punjabi Suba movement, advocating for the creation of a Punjabi-majority state within India. The movement's demands ranged from autonomous statehood within India to a fully sovereign state (Khalistan). Initially, the Indian government resisted these demands, wary of creating another state based on religious grounds. By the late 1970s and 1980s, the Khalistan movement began to militarize, marked by a shift in Sikh nationalism and the rise of armed militancy. This period, especially leading up to and following Operation Blue Star in 1984, saw increased Sikh militancy as a response to perceived injustices and political marginalization.[52]

Violence

After the assassination of Indira Gandhi on 31 October 1984 by two of her Sikh bodyguards, anti-Sikh riots erupted the following day. They continued in some areas for several days, in which 3,000-17,000 people were killed.[4][5] At least 50,000 Sikhs were displaced.[4] Sultanpuri, Mangolpuri, Trilokpuri, and other Trans-Yamuna areas of Delhi were the worst affected. Perpetrators carried iron rods, knives, clubs, and combustible material (including kerosene and petrol). They entered Sikh neighbourhoods, killing Sikhs indiscriminately and destroying shops and houses. Armed mobs stopped buses and trains in and near Delhi, pulling off Sikh passengers for lynching; some were burnt alive. Others were dragged from their homes and hacked to death, and Sikh women were reportedly gang-raped and Sikhs also had acid thrown on them.[53][3]

Such wide-scale violence cannot take place without police help. Delhi Police, whose paramount duty was to upkeep law and order situation and protect innocent lives, gave full help to rioters who were in fact working under able guidance of sycophant leaders like Jagdish Tytler and H K L Bhagat. It is a known fact that many jails, sub-jails and lock-ups were opened for three days and prisoners, for the most part hardened criminals, were provided fullest provisions, means and instruction to "teach the Sikhs a lesson". But it will be wrong to say that Delhi Police did nothing, for it took full and keen action against Sikhs who tried to defend themselves. The Sikhs who opened fire to save their lives and property had to spend months dragging heels in courts after-wards.

— Jagmohan Singh Khurmi, The Tribune [full citation needed]

The grief, trauma, and survival of Sikh victims and witnesses is an important human perspective missing in much factual coverage of the riots. In interviews with Manoj Mitta and H.S. Phoolka for their book "When a Tree Shook Delhi," survivors recount harrowing tales of watching loved ones burned alive, raped, and dismembered. One Hindu woman describes her family sheltering over 70 Sikhs from murderous mobs who were targeting Sikh homes marked with an "S."Ensaaf's 2006 report "Twenty years of impunity" contains dozens of eyewitness statements accusing police and government officials of enabling and even participating in the violence. Personal stories help convey the true horrors endured by the Sikh community.[citation needed][tone]

The riots have also been described as pogroms,[12][13][54] massacres[55][56] or genocide.[57][additional citation(s) needed]

Meetings and weapons distribution

On 31 October, a crowd around the All India Institute of Medical Sciences began shouting vengeance slogans such as "Blood for blood!" and became an unruly mob. At 17:20, President Zail Singh arrived at the hospital and the mob stoned his car. The mob began assaulting Sikhs, stopping cars and buses to pull Sikhs out and burn them.[14] The violence on 31 October, restricted to the area around the AIIMS, resulted in many Sikh deaths.[14] Residents of other parts of Delhi reported that their neighbourhoods were peaceful.

During the night of 31 October and the morning of 1 November, Congress Party leaders met with local supporters to distribute money and weapons. Congress MP Sajjan Kumar and trade-union leader Lalit Maken handed out ₹100 notes and bottles of liquor to the assailants.[14] On the morning of 1 November, Sajjan Kumar was observed holding rallies in the Delhi neighbourhoods of Palam Colony (from 06:30 to 07:00), Kiran Gardens (08:00 to 08:30), and Sultanpuri (about 08:30 to 09:00).[14] In Kiran Gardens at 8:00 am, Kumar was observed distributing iron rods from a parked truck to a group of 120 people and ordering them to "attack Sikhs, kill them, and loot and burn their properties".[14] During the morning he led a mob along the Palam railway road to Mangolpuri, where the crowd chanted: "Kill the Sardars" and "Indira Gandhi is our mother and these people have killed her".[58] In Sultanpuri, Moti Singh (a Sikh Congress Party member for 20 years) heard Kumar make the following speech:

Whoever kills the sons of the snakes, I will reward them. Whoever kills Roshan Singh and Bagh Singh will get 5,000 rupees each and 1,000 rupees each for killing any other Sikhs. You can collect these prizes on 3 November from my personal assistant Jai Chand Jamadar.[note 1]

The Central Bureau of Investigation told the court that during the riot, Kumar said that "not a single Sikh should survive".[22][60] The bureau accused Delhi Police of keeping its "eyes closed" during the riot, which was planned.[22]

In the Shakarpur neighbourhood, Congress Party leader Shyam Tyagi's home was used as a meeting place for an undetermined number of people.[59] According to a local Hindu witness, Minister of Information and Broadcasting H. K. L. Bhagat, gave money to Boop Tyagi (Tyagi's brother), saying: "Keep these two thousand rupees for liquor and do as I have told you ... You need not worry at all. I will look after everything."[59]

During the night of 31 October, Balwan Khokhar (a local Congress Party leader who was implicated in the massacre) held a meeting at Pandit Harkesh's ration shop in Palam.[59] Congress Party supporter Shankar Lal Sharma held a meeting, where he assembled a mob which swore to kill Sikhs, in his shop at 08:30 on 1 November.[59]

Kerosene, the primary mob weapon, was supplied by a group of Congress Party leaders who owned filling stations.[61] In Sultanpuri, Congress Party A-4 block president Brahmanand Gupta distributed oil while Sajjan Kumar "instructed the crowd to kill Sikhs, and to loot and burn their properties" (as he had done at other meetings throughout New Delhi).[61] Similar meetings were held at locations such as Cooperative Colony in Bokaro, where local Congress president and gas-station owner P. K. Tripathi distributed kerosene to mobs.[61] Aseem Shrivastava, a graduate student at the Delhi School of Economics, described the mobs' organised nature in an affidavit submitted to the Misra Commission:

The attack on Sikhs and their property in our locality appeared to be an extremely organized affair ... There were also some young men on motorcycles, who were instructing the mobs and supplying them with kerosene oil from time to time. On more than a few occasions we saw auto-rickshaw arriving with several tins of kerosene oil and other inflammable material, such as jute sacks.[62]

A senior official at the Ministry of Home Affairs told journalist Ivan Fera that an arson investigation of several businesses burned in the riots had found an unnamed combustible chemical "whose provision required large-scale coordination".[63] Eyewitness reports confirmed the use of a combustible chemical in addition to kerosene.[63] The Delhi Sikh Gurdwara Management Committee later cited 70 affidavits noting the use of a highly-flammable chemical in its written reports to the Misra Commission.[61]

Congress Party voter-list use

On 31 October, Congress Party officials provided assailants with voter lists, school registration forms, and ration lists.[64] The lists were used to find Sikh homes and business, an otherwise-impossible task because they were in unmarked, diverse neighbourhoods. During the night of 31 October, before the massacres began, assailants used the lists to mark Sikh houses with an "S".[64] Because most mob members were illiterate, Congress Party officials provided help reading the lists and leading the mobs to Sikh homes and businesses in other neighbourhoods.[61] With the lists, the mobs could pinpoint the location of Sikhs they otherwise would have missed.[61]

Sikh men not at home were easily identified by their turbans and beards, and Sikh women were identified by their dress. In some cases, the mobs returned to locations where they knew Sikhs were hiding because of the lists. Amar Singh escaped the initial attack on his house by having a Hindu neighbour drag him into the neighbour's house and announce that he was dead. A group of 18 assailants later came looking for his body; when his neighbour said that his body had been taken away, an assailant showed him a list and said: "Look, Amar Singh's name has not been struck off from the list, so his body has not been taken away."[61]

International perspectives

Organizations like ENSAAF, a Sikh rights group, have documented the involvement of senior political leaders, notably from the Congress Party, in orchestrating the violence. These organizations have provided detailed accounts of how the violence was not spontaneous but organized, with state machinery used to facilitate the massacres, including using government buses to transport mobs to Sikh localities.[65] Over the years, at least ten different commissions and committees were appointed by the Indian government to investigate the violence. These commissions faced criticism for a lack of transparency and effectiveness. The Misra Commission, for instance, was criticized for its in-camera proceedings and failure to allow victims' lawyers to attend or examine witnesses. Other commissions, such as the Kapoor-Mittal and Jain-Banerjee committees, recommended actions against police officers and politicians, but these recommendations were often not fully acted upon.[66]

The response within India was marked by a call for justice from various quarters, including victims and activists. The Indian government's formation of Special Investigation Teams (SITs) and the extension of their mandates were seen as efforts to address the issue, though some viewed these measures as inadequate. There has been a persistent demand for accountability and justice for the victims and survivors of the riots.[67]

Timeline

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2017) |

31 October

- 09:20: Indira Gandhi is shot by two of her Sikh security guards at her residence, and is rushed to the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS).

- 10:50: Gandhi dies.[68][69]

- 11:00: All India Radio reports that the guards who shot Gandhi were Sikhs.

- 16:00: Rajiv Gandhi returns from West Bengal to the AIIMS, where isolated attacks occur.

- 17:30: The motorcade of President Zail Singh, returning from a foreign visit, is stoned as it approaches the AIIMS. A bodyguard's turban is ripped off.[70]

Evening and night

- Organized, equipped gangs spread out from the AIIMS.

- Attacks are planned in a meeting at the home of the Minister of Information and Broadcasting[70]

- Violence towards Sikhs and destruction of Sikh property spreads.

- The "Seek blood for blood" statement is aired on state-controlled airwaves.[71]

- Rajiv Gandhi is sworn in as Prime Minister.

- Senior advocate and BJP leader Ram Jethmalani meets Home Minister P. V. Narasimha Rao and urges him to take immediate steps to protect Sikhs from further attacks.

- At night, homes of Sikh are identified by surveyors. They use lists to find homes, marking homes of Sikhs with an S.[72]

- At around 9 p.m. an elderly Sikh man is the first to be killed.[71]

- Delhi lieutenant governor P. G. Gavai and police commissioner S. C. Tandon visit the affected areas.

1 November

- Early in the morning organised mobs are transported outside of Delhi on buses and begin attacking Sikh neighbourhoods. They are equipped with firearms, knives, iron rods, clubs, and kerosene.[73]

- In the morning, Gurdwaras are attacked and burned.[74]

- At 7:00 a.m. mobs in Kanpur vandalise Sikh shops and loot Sikh homes. Local Congress leaders soon begin to lead mobs. Rapes and killings begin and continue till 4 November.[75]

- In the morning, mobs roam the Trilokpuri colony in East Delhi. In two narrow alleys of the colony, hundreds of Sikhs were "butchered" throughout the day. The killings continued for multiple days. According to an eyewitness, Sikhs were able to fend off some of the mobs. Police forces then came and stripped Sikhs of their weapons, and blocked all exit points. This left the Sikhs defenceless and vulnerable to the mobs.[76]

- In Trilokpuri colony: A father and his two sons were beaten and burned alive by a gang. The gang entered their home where a woman and her youngest son were found. She was stripped and raped by boys in front of her son. The woman tried to flee with her son after the rape, but the son was caught by a mob that beat him and burned him alive. The woman was also beaten and suffered multiple knife wounds and a broken arm.[77]

- In Trilokpuri colony: Women were grouped together and were dragged one by one to a mosque where they would be gang raped. According to one girl, she was raped by 15 men.[77]

- In Trilokpuri colony: 30 women are abducted and held in Chilla near Delhi. Some of the women were released on 3 November while the fate of the remaining women is unknown.[77]

- 09:00: Armed mobs take over the streets in Delhi. Gurdwaras are among the first targets. The worst-affected areas are low-income neighbourhoods such as Inderlok (erstwhile Trilokpuri), Shahdara, Geeta Colony, Mongolpuri, Sultanpuri and Palam Colony. Areas with prompt police intervention, such as Farsh Bazar and Karol Bagh, see few killings and little major violence.

- According to an eyewitness in Bihar, in the morning large crowds armed with weapons raised anti-Sikh chants and attacked the homes of Sikh. They broke into the eyewitnesses home and dragged out her parents and three brothers. They were each "butchered" as she watched helplessly.[78]

- At 6 PM a mob under the guidance of Congress leader Lalit Maken set fire to Pataudi's Gurdwara which created a panic in the city. As the armed mob rampaged through the town and set fire to Sikh homes in the city, one group of Sikhs escaped to the outskirts while another found shelter in a local Ashram.[79]

2 November

- Trains arrive in Delhi with dead bodies of Sikhs.[80]

- 17 Sikhs were burned alive in Pataudi.[78]

- In Pataudi, two teenage Sikh women were dragged in the middle of a street where they were stripped naked. They were beaten and urinated on. They were finally burned alive.[78]

- 500 armed men were allegedly transported in trucks to Hondh-Chillar. They yelled anti Sikh slogans before burning Sikhs alive in their homes and gang raping women.[81]

- A curfew is announced in Delhi, but is not enforced. Although the army is deployed throughout the city, the police did not co-operate with soldiers (who are forbidden to fire without the consent of senior police officers and executive magistrates).

3 November

- By late evening, army and local police units work together to subdue the violence. After law-enforcement intervention, violence is comparatively mild and sporadic. In Delhi, the bodies of riot victims are brought to the All India Institute of Medical Sciences and the Civil Hospital mortuary in Delhi.[82]

Aftermath

The Delhi High Court, delivering its verdict on a riot-related case in 2009, said:[83]

Though we boast of being the world's largest democracy and the Delhi being its national capital, the sheer mention of the incidents of 1984 anti-Sikh riots in general and the role played by Delhi Police and state machinery in particular makes our heads hang in shame in the eyes of the world polity.

The government allegedly destroyed evidence and shielded the guilty. Asian Age, an Indian daily newspaper, ran a front-page story calling the government actions "the mother of all cover-ups".[84][85]

From 31 October 1984 to 10 November 1984 the People's Union for Democratic Rights and the People's Union for Civil Liberties conducted an inquiry into the riots, interviewing victims, police officers, neighbours of the victims, army personnel and political leaders. In their joint report, "Who Are The Guilty", the groups concluded:

The attacks on members of the Sikh Community in Delhi and its suburbs during the period, far from being a spontaneous expression of "madness" and of popular "grief and anger" at Mrs. Gandhi's assassination as made out to be by the authorities, were the outcome of a well organised plan marked by acts of both deliberate commissions and omissions by important politicians of the Congress (I) at the top and by authorities in the administration.[21]

According to eyewitness accounts obtained by Time magazine, Delhi police looked on as "rioters murdered and raped, having gotten access to voter records that allowed them to mark Sikh homes with large Xs, and large mobs being bused in to large Sikh settlements".[86] Time reported that the riots led to only minor arrests, with no major politicians or police officers convicted. The magazine quoted Ensaaf,[87] an Indian human-rights organisation, as saying that the government attempted to destroy evidence of its involvement by refusing to record First Information Reports.[86]

A 1991 Human Rights Watch report on violence between Sikh separatists and the Government of India traced part of the problem to government response to the violence:

Despite numerous credible eye-witness accounts that identified many of those involved in the violence, including police and politicians, in the months following the killings, the government sought no prosecutions or indictments of any persons, including officials, accused in any case of murder, rape or arson.[88]

The violence was allegedly led (and often perpetrated) by Indian National Congress activists and sympathizers. The Congress-led government was widely criticised for doing little at the time and possibly conspiring in the riots, since voter lists were used to identify Sikh families.[23] Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP) members also allegedly participated in the violence.[89]

The riots catalyzed lasting political and social changes among India's Sikhs. With the government failing to protect them, many Sikhs felt betrayed and marginalized, providing momentum to the Khalistan separatist movement.

Revenge killings

On 31 July 1985, Harjinder Singh Jinda, Sukhdev Singh Sukha and Ranjit Singh Gill of the Khalistan Commando Force assassinated Congress Party leader and Member of Parliament Lalit Maken in retaliation for the riots. The 31-page report, "Who Are The Guilty?", listed 227 people who led the mobs; Maken was third on the list.[90]

On 5 September 1985, Harjinder Singh Jinda and Sukhdev Singh Sukha assassinated Congress (I) leader and member of Delhi Metropolitan Council Arjan Dass because of his involvement in the riots. Dass appeared in affidavits submitted by Sikh victims to the Nanavati Commission, headed by retired Supreme Court of India judge G. T. Nanavati.[91]

On 8 April 1988, Vilayati Ram Kaytal a Congress MLA of Uttar Pradesh was assassinated over his involvement in the riots. He allegedly led mobs.[92][93]

On 19 December 1991, Sikh militants killed 14 people. Among the 14 was Lala Ram. Ram was a Hindu militant who had been accused of inciting violence in the riots.[94][95]

In 2009 Khalistan Liberation Force members killed Dr. Budh Parkash Kashyap over his involvement in the riots.[96]

Convictions

In 1995, Delhi Chief Minister Madan Lal Khurana said 46 persons have been prosecuted for their role in the riots.[97]

In Delhi, 442 rioters were convicted as of 2012. Forty-nine were sentenced to the life imprisonment, and another three to more than 10 years' imprisonment. Six Delhi police officers were sanctioned for negligence during the riots.[98] In April 2013, the Supreme Court of India dismissed the appeal of three people who had challenged their life sentences.[99] That month, the Karkardooma district court in Delhi convicted five people – Balwan Khokkar (former councillor), Mahender Yadav (former MLA), Kishan Khokkar, Girdhari Lal and Captain Bhagmal – for inciting a mob against Sikhs in Delhi Cantonment. The court acquitted Congress leader Sajjan Kumar, which led to protests.[100]

In the first ever case of capital punishment in the 1984 anti-Sikh riots case death sentence was awarded to Yashpal Singh convicted for murdering two persons, 24-year-old Hardev Singh and 26-year-old Avtar Singh, in Mahipal Pur area of Delhi on 1 November 1984. Additional Sessions Judge Ajay Pandey pronounced the Judgement on 20 November 34 years after the crime was committed. The second convict in the case, Naresh Sehrawat was awarded life imprisonment. The Court considered the failing health of 68-year-old Sehrawat while giving him a lighter sentence. The conviction followed a complaint by the deceased Hardev Singh's elder brother Santokh Singh. Though an FIR was filed on the same day of the crime nothing came of the case as a Congress leader, JP Singh, who led the mob was acquitted in the case. A fresh FIR was filed on 29 April 1993, following recommendations of the Ranganath Commission of inquiry. The police closed the matter as untraced despite witness testimonies of the deceased's four brothers who were witness to the crime. The case was reopened by the Special Investigation Team constituted by the BJP-led NDA government on 12 February 2015. The SIT completed the investigation in record time.[33][34] The first conviction resulting from the formation of the SIT came on 15 November 2018, by the conviction of Naresh Sehrawat and Yashpal Singh.[35]

In December 2018, in one of the first high-profile convictions, former Congress leader Sajjan Kumar was sentenced to life imprisonment by the Delhi High Court based on the re-opened investigation by the Special Investigation Team constituted by the NDA government in 2015.[32] On 20 September 2023, Kumar was acquitted over one case of murder in the riot.[101]

Investigations

Ten commissions or committees have been formed to investigate the riots. The most recent, headed by Justice G. T. Nanavati, submitted its 185-page report to Home Minister Shivraj Patil on 9 February 2005; the report was tabled in Parliament on 8 August of that year. The commissions below are listed in chronological order. Many of the accused were acquitted or never formally charged.

Marwah Commission

The Marwah Commission was appointed in November 1984. Ved Marwah, Additional Commissioner of Police, was tasked with enquiring into the role of the police during the riots. Many of the accused Delhi Police officers were tried in the Delhi High Court. As Marwah was completing his inquiry in mid-1985, he was abruptly directed by the Home Ministry not to proceed further.[102] The Marwah Commission records were appropriated by the government, and most (except for Marwah's handwritten notes) were later given to the Misra Commission.

Misra Commission

The Misra Commission was appointed in May 1985; Justice Rangnath Misra was a judge on the Supreme Court of India. Misra submitted his report in August 1986, and the report was made public in February 1987. In his report, he said that it was not part of his terms of reference to identify any individual and recommended the formation of three committees.

The commission and its report was criticised as biased by the People's Union for Civil Liberties and Human Rights Watch. According to a Human Rights Watch report on the commission:

It recommended no criminal prosecution of any individual, and it cleared all high-level officials of directing the pogroms. In its findings, the commission did acknowledge that many of the victims testifying before it had received threats from local police. While the commission noted that there had been "widespread lapses" on the part of the police, it concluded that "the allegations before the commission about the conduct of the police are more of indifference and negligence during the riots than of any wrongful overt act."[88]

The People's Union for Civil Liberties criticised the Misra Commission for concealing information on the accused while disclosing the names and addresses of victims.[103]

Kapur Mittal Committee

The Kapur Mittal Committee was appointed in February 1987 at the recommendation of the Misra Commission to enquire into the role of the police; the Marwah Commission had almost completed a police inquiry in 1985 when the government asked that committee not to continue. This committee consisted of Justice Dalip Kapur and Kusum Mittal, retired Secretary of Uttar Pradesh. It submitted its report in 1990, and 72 police officers were cited for conspiracy or gross negligence. Although the committee recommended the dismissal of 30 of the 72 officers, none have been punished.

Jain Banerjee Committee

The Jain Banerjee Committee was recommended by the Misra Commission for the registration of cases. The committee consisted of former Delhi High Court judge M. L. Jain and retired Inspector General of Police A. K. Banerjee.

In its report, the Misra Commission stated that many cases (particularly those involving political leaders or police officers) had not been registered. Although the Jain Banerjee Committee recommended the registration of cases against Sajjan Kumar in August 1987, no case was registered.

In November 1987, press reports criticised the government for not registering cases despite the committee's recommendation. The following month, Brahmanand Gupta (accused with Sajjan Kumar) filed a writ petition in the Delhi High Court and obtained a stay of proceedings against the committee which was not opposed by the government. The Citizen's Justice Committee filed an application to vacate the stay. The writ petition was decided in August 1989 and the high court abolished the committee. An appeal was filed by the Citizen's Justice Committee in the Supreme Court of India.

Potti Rosha Committee

The Potti Rosha Committee was appointed in March 1990 by the V.P. Singh government as a successor to the Jain Banerjee Committee. In August 1990, the committee issued recommendations for filing cases based on affidavits submitted by victims of the violence; there was one against Sajjan Kumar. When a CBI team went to Kumar's home to file the charges, his supporters held and threatened them if they persisted in pursuing Kumar. When the committee's term expired in September 1990, Potti and Rosha decided to end their inquiry.

Jain Aggarwal Committee

The Jain Aggarwal Committee was appointed in December 1990 as a successor to the Potti Rosha Committee. It consisted of Justice J. D. Jain and retired Uttar Pradesh Director General of Police D. K. Aggarwal. The committee recommended the registration of cases against prominent Congress leaders like H. K. L. Bhagat, Sajjan Kumar, Dharamdas Shastri and Jagdish Tytler.[104] These cases weren't registered by police.

It suggested establishing two or three special investigating teams in the Delhi Police under a deputy commissioner of police, supervised by an additional commissioner of police answerable to the CID, and a review of the work-load of the three special courts set up to deal with the riot cases. The appointment of special prosecutors to deal the cases was also discussed. The committee was wound up in August 1993, but the cases it recommended were not registered by the police.

Ahuja Committee

The Ahuja Committee was the third committee recommended by the Misra Commission to determine the total number of deaths in Delhi. According to the committee, which submitted its report in August 1987, 2,733 Sikhs were killed in the riots.

Dhillon Committee

The Dhillon Committee, headed by Gurdial Singh Dhillon, was appointed in 1985 to recommend measures for the rehabilitation of victims. The committee submitted its report by the end of the year.[vague] One major recommendation was that businesses with insurance coverage whose claims were denied should receive compensation as directed by the government. Although the committee recommended ordering the (nationalised) insurance companies to pay the claims, the government did not accept its recommendation and the claims were not paid.

Narula Committee

The Narula Committee was appointed in December 1993 by the Madan Lal Khurana-led BJP government in Delhi. One recommendation of the committee was to convince the central government to impose sanctions.

Khurana took up the matter with the central government, which in the middle of 1994, the Central Government decided that the matter did not fall within its purview and sent the case to the lieutenant governor of Delhi. It took two years for the P. V. Narasimha Rao government to decide that it did not fall within its purview.

The Narasimha Rao Government further delayed the case. The committee submitted its report in January 1994, recommending the registration of cases against H. K. L. Bhagat and Sajjan Kumar. Despite the central-government delay, the CBI filed the charge sheet in December 1994.

The Nanavati Commission

The Nanavati Commission was established in 2000 after some dissatisfaction was expressed with previous reports.[105] The Nanavati Commission was appointed by a unanimous resolution passed in the Rajya Sabha. This commission was headed by Justice G.T. Nanavati, retired Judge of the Supreme Court of India. The commission submitted its report in February 2004. The commission reported that recorded accounts from victims and witnesses "indicate that local Congress leaders and workers had either incited or helped the mobs in attacking the Sikhs".[105] Its report also found evidence against Jagdish Tytler "to the effect that very probably he had a hand in organising attacks on Sikhs".[105] It also said that P.V. Narasimha Rao was asked to send the army to stop the violence. Rao responded with saying that he would look into it.[106] It also recommended that Sajjan Kumar's involvement in the rioting required a closer look. The commission's report also cleared Rajiv Gandhi and other high ranking Congress (I) party members of any involvement in organising riots against Sikhs. It did find, however, that the Delhi Police fired about 392 rounds of bullets, arrested approximately 372 persons, and "remained passive and did not provide protection to the people" throughout the rioting.[105][6]

Role of Jagdish Tytler

The Central Bureau of Investigation closed all cases against Jagdish Tytler in November 2007 for his alleged criminal conspiracy to engineer riots against Sikhs in the aftermath of Indira Gandhi's assassination. The bureau submitted a report to the Delhi court that no evidence or witness was found to corroborate allegations that Tytler led murderous mobs during 1984.[107] It was alleged in court that Tytler – then an MP – complained to his supporters about the relatively-"small" number of Sikhs killed in his constituency (Delhi Sadar), which he thought had undermined his position in the Congress Party.[108]

In December 2007 a witness, Dushyant Singh (then living in California), appeared on several private television news channels in India saying that he was never contacted by the CBI. The opposition Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) demanded an explanation in Parliament from Minister of State for Personnel Suresh Pachouri, who was in charge of the CBI. Pachouri, who was present, refused to make a statement.[109] Additional Chief Metropolitan Magistrate of the Delhi Court Sanjeev Jain, who had dismissed the case against Tytler after the CBI submitted a misleading report, ordered the CBI to reopen cases against Tytler related to the riots on 18 December 2007.[110]

In December 2008 a two-member CBI team went to New York to record statements from Jasbir Singh and Surinder Singh, two eyewitnesses. The witnesses said that they saw Tytler lead a mob during the riot, but did not want to return to India because they feared for their safety.[111] They blamed the CBI for not conducting a fair trial, accusing the bureau of protecting Tytler.

In March 2009, the CBI cleared Tytler amidst protests from Sikhs and the opposition parties.[112] On 7 April, Sikh Dainik Jagran reporter Jarnail Singh threw his shoe at Home Minister P. Chidambaram to protest the clearing of Tytler and Sajjan Kumar. Because of the upcoming Lok Sabha elections, Chidambaram did not press charges.[113]

Two days later, over 500 protesters from Sikh organisations throughout India gathered outside the court which was scheduled to hear the CBI's plea to close the case against Tytler. Later in the day, Tytler announced that he was withdrawing from the Lok Sabha elections to avoid embarrassing his party. This forced the Congress Party to cut the Tytler and Sajjan Kumar Lok Sabha tickets.[114]

On 10 April 2013, the Delhi court ordered the CBI to reopen the 1984 case against Tytler. The court ordered the bureau to investigate the killing of three people in the riot case, of which Tytler had been cleared.[115] In 2015, Delhi Court directed the CBI to include Billionaire arms dealer Abhishek Verma as the main witness in this case against Tytler. Following court's directions, Verma's testimony was recorded by the CBI and the case was reopened. Polygraph (lie-detector) test was ordered by the court to be conducted on witness Verma and also on Tytler after obtaining their consent.[116] Verma consented, Tytler declined to be tested. Thereafter, Verma started to receive threat calls and letters in which he was threatened to be blownup and his family also would be blown up if he testifies against Tytler. The Delhi High Court directed Delhi Police to provide 3x3 security cover of 9 armed police bodyguards to Verma and his family on round the clock basis.[117][118]

New York civil case

Sikhs for Justice, a U.S.-based NGO, filed a civil suit in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York on 14 March 2011 accusing the Indian government of complicity in the riots. The court issued a summons to the Congress Party and Kamal Nath, who was accused by the Nanavati commission of encouraging rioters.[119][120][121] The complaint against Nath was dismissed in March 2012 by Judge Robert W. Sweet, who ruled that the court lacked jurisdiction in the case.[122] The 22-page order granted Nath's motion to dismiss the claim, with Sweet noting that Sikhs for Justice failed to "serve the summons and its complaints to Nath in an appropriate and desired manner".[123] On 3 September 2013, a federal court in New York issued a summons to Sonia Gandhi for her alleged role in protecting participants in the riots.[124] A U.S. court dismissed the lawsuit against Gandhi on 11 July 2014.[125]

Cobrapost operation

According to an April 2014 Cobrapost sting operation, the government muzzled the Delhi Police during the riots. Messages were broadcast directing the police not to act against rioters, and the fire brigade would not go to areas where cases of arson were reported.[126]

Special Investigation Team (Supreme Court)

In January 2018, the Supreme Court of India decided to form a three-member Special Investigation Team (SIT) of its own to probe 186 cases related to 1984 anti-Sikh riots that were not further investigated by Union Government formed SIT. This SIT would consists of a former High court judge, a former IPS officer whose rank is not less than or equivalent to Inspector general and a serving IPS Officer.[127]

Recognition as a genocide

While there has been no formal state recognition of the 1984 massacre as a genocide, Sikh communities both in India and the diaspora continue to lobby for its acknowledgment.[128]

India

The Jathedar of the Akal Takht, the head figure of Sikhs worldwide, declared the events following the death of Indira Gandhi a Sikh "genocide" on 15 July 2010, replacing the term "anti-Sikh riots" widely used by the Indian government, the media, and writers.[129] This decision came soon after a similar motion was raised in the Canadian Parliament.[130]

In 2019, Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi referred to the "1984 riots" as a 'horrendous genocide'.[131]

United States

In October 2024, four US Members of congress, David Valadao and Jim Costa as well as co-chairs of the American Sikh Congressional Caucus introduced a resolution to recognise and commemorate the Sikh Genocide of 1984 formally.[132]

California

On 16 April 2015, Assembly Concurrent Resolution 34 (ACR 34) was passed by the California State Assembly. Co-authored by Sacramento-area assembly members Jim Cooper, Kevin McCarty, Jim Gallagher and Ken Cooley, the resolution criticized the Government for participating in and failing to prevent the killings. The assembly called the killings a "genocide", as it "resulted in the intentional destruction of many Sikh families, communities, homes and businesses."[133][134]

Connecticut

In February 2018, American state of Connecticut, passed a bill stating, 30 November of each year to be "Sikh Genocide" Remembrance Day to remember the lives lost on 30 November 1984, during the Sikh Genocide.[135]

Canada

In 2024, Canada's New Democratic Party (NDP) planned to seek recognition of the '1984 Sikh Genocide' in the country's parliament on its 40th anniversary.[136]

Ontario

In April 2017, the Ontario Legislature passed a motion condemning the anti-Sikh riots as "genocide".[137] The Indian government lobbied against the motion and condemned it upon its adoption. In 2024, the City of Brampton, Ontario recognised 'Sikh Genocide Week'.[138]

Australia

In 2012, Australian MP Warren Entsch tabled a petition of more than 4,000 signatures, calling for the government to recognise the killing of Sikhs in India in 1984 as a genocide.[139]

Impact and legacy

On 12 August 2005 , then Prime Minister of India Dr. Manmohan Singh apologised in the Lok Sabha for the riots.[140][141] The riots are cited as a reason to support the creation of a Sikh homeland in India, often called Khalistan.[142][143][144]

On 15 January 2017, the Wall of Truth was inaugurated in Lutyens' Delhi, New Delhi, as a memorial for Sikhs killed during the 1984 riots (and other hate crimes across the world).[145][146]

In popular culture

The anti-Sikh riots have been the subject of several films and novels:

- The 2022 Netflix movie Jogi, starring Diljit Dosanjh, directed by Ali Abbas Zafar, is set against the backdrop of the 1984 anti-Sikh riots in Trilokpuri, Delhi. It tells the story of a Sikh man named Jogi whose goal is to save his family, friends and fellow neighbours from a massacre that killed thousands of Sikhs.

- The 2021 web television series Grahan, starring Pavan Malhotra, Wamiqa Gabbi, and Zoya Hussain, and created by Shailendra Kumar Jha and directed by Ranjan Chandel, for Hotstar, is inspired by Satya Vyas' popular novel Chaurasi. It is the first series to deal with the 1984 anti-Sikh riots that happened in Bokaro, Jharkhand. The series is centered on the nexus between politics and law enforcement.

- The 2005 English film Amu, by Shonali Bose and starring Konkona Sen Sharma and Brinda Karat, is based on Shonali Bose's novel of the same name. The film tells the story of a girl, orphaned during the riots, who reconciles with her adoption years later. Although it won the National Film Award for Best Feature Film in English, it was censored in India but was released on DVD without the cuts.[147]

- The 2004 Hindi film Kaya Taran (Chrysalis), directed by Shashi Kumar and starring Seema Biswas, is based on the Malayalam short story "When Big Tree Falls" by N.S. Madhavan. The film revolves around a Sikh woman and her young son, who took shelter in a Meerut nunnery during the riots.

- The 2003 Bollywood film Hawayein, a project of Babbu Maan and Ammtoje Mann, is based on the aftermath of Indira Gandhi's assassination, the 1984 riots and the subsequent victimisation of the Punjabi people.

- Mamoni Raisom Goswami's Assamese novel, Tej Aru Dhulire Dhusarita Prishtha (Pages Stained with Blood), focuses on the riots.

- Khushwant Singh and Kuldip Nayar's book, Tragedy of Punjab: Operation Bluestar & After, focuses on the events surrounding the riots.

- Jarnail Singh's non-fiction book, I Accuse, describes incidents which occurred during the riots.

- Uma Chakravarthi and Nandita Hakser's book, The Delhi Riots: Three Days in the Life of a Nation, has interviews with victims of the Delhi riots.

- H. S. Phoolka and human-rights activist and journalist Manoj Mitta wrote the first account of the riots, When a Tree Shook Delhi.

- HELIUM (a novel of 1984, published by Bloomsbury in 2013) by Jaspreet Singh]

- The 2014 Punjabi film, Punjab 1984 with Diljit Dosanjh, is based on the aftermath of Indira Gandhi's assassination, the riots and the subsequent victimisation of the Punjabi people.

- The 2016 Bollywood film, 31st October with Vir Das, is based on the riots.

- The 2016 Punjabi film, Dharam Yudh Morcha, is based on the riots.

- The 2001 Star Trek novel The Eugenics Wars: The Rise and Fall of Khan Noonien Singh by Gary Cox, a 14-year-old Khan, who is depicted as a North Indian from a family of Sikhs, is caught up in the riots while reading in a used book stall in Nai Sarak. He is injured, doused with kerosene and nearly set on fire by a mob before being rescued by Gary Seven.

See also

- Black July (1985)

- Nellie massacre (1983)

- Operation Blue Star (1984)

- List of massacres in India

- Air India Flight 182

Notes

References

- ^ a b Brass, Paul R. (2016). Riots and Pogroms. Springer. ISBN 9781349248674. Archived from the original on 6 September 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ Paul Brass (October 1996). Riots and Pogroms. NYU Press. p. 201. ISBN 9780814712825. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ a b "The Tribune, Chandigarh, India – Perspective". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Joseph, Paul (11 October 2016). The SAGE Encyclopedia of War: Social Science Perspectives. SAGE. p. 433. ISBN 978-1483359885.

around 17,000 Sikhs were burned alive or killed

- ^ a b c d e Bedi, Rahul (1 November 2009). "Indira Gandhi's death remembered". BBC. Archived from the original on 2 November 2009. Retrieved 2 November 2009.

The 25th anniversary of Indira Gandhi's assassination revives stark memories of some 3,000 Sikhs killed brutally in the orderly pogrom that followed her killing

- ^ a b "What Delhi HC Order on 1984 Anti-Sikh Pogrom Says About 2002 Gujarat Riots". Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Why Gujarat 2002 Finds Mention in 1984 Riots Court Order on Sajjan Kumar". Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ a b Nelson, Dean (30 January 2014). "Delhi to reopen inquiry in to massacre of Sikhs in 1984 riots". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ Jeffrey M. Shaw; Timothy J. Demy (27 March 2017). War and Religion: An Encyclopedia of Faith and Conflict [3 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 129. ISBN 978-1610695176. Archived from the original on 26 April 2022. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ Paul R. Brass (October 1996). Riots and Pogroms. NYU Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0814712825. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ a b State pogroms glossed over. The Times of India. 31 December 2005.

- ^ a b "Anti-Sikh riots a pogrom: Khushwant". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 22 October 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Kaur, Jaskaran; Crossette, Barbara (2006). Twenty years of impunity: the November 1984 pogroms of Sikhs in India (PDF) (2nd ed.). Portland, OR: Ensaaf. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-9787073-0-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ "Jagdish Tytler's role in 1984 anti-Sikh riots to be re-investigated". NDTV.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ Pillalamarri, Akhilesh. "India's Anti-Sikh Riots, 30 Years On". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ "1984: Assassination and revenge". BBC News. 31 October 1984. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- ^ Westerlund, David (1996). Questioning The Secular State: The Worldwide Resurgence of Religion in Politics. C. Hurst & Co. p. 1276. ISBN 978-1-85065-241-0.

- ^ "1984, the State, a Carnage and What the Trauma of a People Means to India Today". thewire.in. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ "1984 anti-Sikh riots: Compensation still a dream but a sense of closure for victim families as SIT makes arrests". The Hindustan Times. 1 November 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ a b Mukhoty, Gobinda; Kothari, Rajni (1984), Who are the Guilty ?, People's Union for Civil Liberties, archived from the original on 5 September 2019, retrieved 4 November 2010

- ^ a b c d "1984 anti-Sikh riots backed by Govt, police: CBI". IBN Live. 23 April 2012. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ a b Swadesh Bahadur Singh (editor of the Sher-i-Panjâb weekly): "Cabinet berth for a Sikh", The Indian Express, 31 May 1996.

- ^ Dead silence: the legacy of human rights abuses in Punjab. Human Rights Watch. May 1994. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-56432-130-5. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ "1984 riots were 'Sikh genocide': Akal Takht – Hindustan Times". Hindustan Times. 14 July 2010. Archived from the original on 17 July 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ "1984 anti-Sikh riots: Congress leader Jagdish Tytler gets anticipatory bail". livemint.com. 5 August 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ Bureau, The Hindu (20 September 2023). "Ex-Congress MP Sajjan Kumar acquitted in 1984 anti-Sikh riots case". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ World Report 2011: India (PDF). Human Rights Watch. 2011. pp. 1–5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ "US saw Cong hand in Sikh massacre, reveal Wiki leaks". The Times of India. 6 May 2011. Archived from the original on 25 November 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- ^ "US refuses to declare 1984 anti-Sikh riots in India as genocide". Washington: CNN-IBN. Press Trust of India. 2 April 2013. Archived from the original on 6 April 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ "India: Bring Charges for Newly Discovered Massacre of Sikhs". Human Rights Watch. 25 April 2011. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- ^ a b "1984 anti-Sikh riots: Sajjan Kumar convicted! HC reverses acquittal, hands life term to Congress leader". 17 December 2018. Archived from the original on 17 December 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ a b "The Tribune, Chandigarh, India : Latest news, India, Punjab, Chandigarh, Haryana, Himachal, Uttarakhand, J&K, sports, cricket". Archived from the original on 30 November 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ a b "Delhi court awards death penalty in 1984 anti-Sikh riots case: Chronology of events". India Today. 22 November 2018.

- ^ a b "A first for SIT: Two convicted for 1984 killings". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 11 January 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ Singh, Khushwant (2004). "The Anandpur Sahib Resolution and Other Akali Demands". Oxfordscholarship.com. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195673098.001.0001. ISBN 9780195673098. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ^ a b Ray, Jayanta Kumar (2007). Aspects of India's International Relations, 1700 to 2000: South Asia and the World. Pearson Education India. p. 484. ISBN 9788131708347. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ Giorgio Shani (2008). Sikh nationalism and identity in a global age. Routledge. pp. 51–60. ISBN 978-0-415-42190-4.

- ^ Joshi, Chand, Bhindranwale: Myth and Reality (New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House, 1984), p. 129.

- ^ Karim, Afsir (1991). Counter Terrorism, the Pakistan Factor. Lancer Publishers. ISBN 978-8170621270. Archived from the original on 26 March 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ a b Karim 1991, pp. 32–33.

- ^ a b Robert L. Hardgrave; Stanley A. Kochanek (2008). India: Government and Politics in a Developing Nation. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-00749-4. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ Robert J. Art; Louise Richardson (2007). Democracy and Counterterrorism: Lessons from the Past. US Institute of Peace Press. p. 444. ISBN 978-1-929223-93-0. Archived from the original on 26 March 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ Tully, Mark; Jacob, Satish (1985). "deaths+in+violent" Amritsar; Mrs. Gandhi's Last Battle (e-book ed.). London. p. 147, Ch. 11. ISBN 9780224023283. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Operation BlueStar, 20 Years On". Rediff.com. 6 June 1984. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ "Army reveals startling facts on Bluestar". The Tribune. 30 May 1984. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ White Paper on the Punjab Agitation. Shiromani Akali Dal and Government of India. 1984. p. 169. Archived from the original on 14 December 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ Charny, Israel W. (1999). Encyclopaedia of genocide. ABC-CLIO. pp. 516–517. ISBN 978-0-87436-928-1. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ "Operation Blue Star: India's first tryst with militant extremism & Updates at Daily News & Analysis". Daily News and Analysis. 5 November 2016. Archived from the original on 3 November 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ Singh, Pritam (2008). Federalism, Nationalism and Development: India and the Punjab Economy. Routledge. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-415-45666-1. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ^ Mahmood, Cynthia Keppley (1989). "Sikh Rebellion and the Hindu Concept of Order". Asian Survey. 29 (3): 326–340. doi:10.2307/2644668. JSTOR 2644668.

- ^ Shani, Giorgio; Singh, Gurharpal, eds. (2021), "Militancy, Antiterrorism and the Khalistan Movement, 1984–1997", Sikh Nationalism, New Approaches to Asian History, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 132–162, doi:10.1017/9781316479940.008, ISBN 978-1-107-13654-0, S2CID 244442106, retrieved 9 December 2023

- ^ Singh, Jaspreet, "India's pogrom, 1984", International New York Times, 31 October 2014, p. 7

- ^ Grewal, Jyoti (30 December 2007). Betrayed by the State: The Anti-Sikh Pogrom of 1984. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-306303-2.

- ^ McLeod, W. H. Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. 2005, page xiv

- ^ Yoo, David. New Spiritual Homes: Religion and Asian Americans. 1999, page 129

- ^ "It's Time India Accept Responsibility for its 1984 Sikh Genocide". Time. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ Kaur, Jaskaran; Crossette, Barbara (2006). Twenty years of impunity: the November 1984 pogroms of Sikhs in India (PDF) (2nd ed.). Portland, OR: Ensaaf. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0-9787073-0-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Kaur, Jaskaran; Crossette, Barbara (2006). Twenty years of impunity: the November 1984 pogroms of Sikhs in India (PDF) (2nd ed.). Portland, OR: Ensaaf. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-9787073-0-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ "India Congress leader 'incited' 1984 anti-Sikh riots". BBC News. 23 April 2012. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kaur, Jaskaran; Crossette, Barbara (2006). Twenty years of impunity: the November 1984 pogroms of Sikhs in India (PDF) (2nd ed.). Portland, OR: Ensaaf. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-9787073-0-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ "Misra Commission Affidavit of Aseem Shrivastava". New Delhi. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ a b Fera, Ivan (23 December 1985). "The Enemy Within". The Illustrated Weekly of India.

- ^ a b Rao, Amiya; Ghose, Aurobindo; Pancholi, N. D. (1985). "3". Truth about Delhi violence: report to the nation. India: Citizens for Democracy. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ "India: No Justice for 1984 Anti-Sikh Bloodshed | Human Rights Watch". 29 October 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ Ramakrishnan, Shriya. "Renewed calls for justice in India's 1984 riots". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ "Lessons of the 1984 Sikh Massacre". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ "Indian prime minister shot dead". BBC News. 31 October 1984. Archived from the original on 17 January 2009. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ^ "Assassination and revenge". BBC News. 31 October 1984. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ^ a b Singh, Pav (2017). 1984: India's Guilty Secret. Kashi House. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-1-911271-08-6.

- ^ a b Singh, Pav (2017). 1984: India's Guilty Secret. Kashi House. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-911271-08-6.

- ^ Singh, Pav (2017). 1984: India's Guilty Secret. Kashi House. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-911271-08-6.

- ^ Singh, Pav (2017). 1984: India's Guilty Secret. Kashi House. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-911271-08-6.

- ^ Singh, Pav (2017). 1984: India's Guilty Secret. Kashi House. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-911271-08-6.

- ^ Singh, Pav (2017). 1984: India's Guilty Secret. Kashi House. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-911271-08-6.

- ^ Singh, Pav (2017). 1984: India's Guilty Secret. Kashi House. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-1-911271-08-6.

- ^ a b c Singh, Pav (2017). 1984: India's Guilty Secret. Kashi House. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-1-911271-08-6.

- ^ a b c Singh, Pav (2017). 1984: India's Guilty Secret. Kashi House. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-911271-08-6.

- ^ "1984. Genocide in Pataudi. Not a whisper escaped". Tehelka. Tehelka. 12 March 2011. Archived from the original on 10 March 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ Singh, Pav (2017). 1984: India's Guilty Secret. Kashi House. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-911271-08-6.

- ^ Singh, Pav (2017). 1984: India's Guilty Secret. Kashi House. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-911271-08-6.

- ^ "My job didn't stop with Mrs Gandhi or Beant Singh. Bodies kept coming". Outlook India. Archived from the original on 13 August 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ^ 1984 riots: three held guilty of rioting. The Indian Express. 23 August 2009.

- ^ Mustafa, Seema (9 August 2005). "1984 Sikh Massacres: Mother of All Cover-ups". The Sikh Times. The Asian Age. Archived from the original on 7 March 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ Agal, Renu (11 August 2005). "Justice delayed, justice denied". Delhi: BBC News. Archived from the original on 26 April 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ a b Mridu Khullar (28 October 2009). "India's 1984 Anti-Sikh Riots: Waiting for Justice". Time. Archived from the original on 1 November 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ "Ensaaf › About Us". ensaaf.org. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ a b Patricia Gossman (1991), Punjab in Crisis (PDF), Human Rights Watch, archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2009, retrieved 4 November 2010

- ^ Inderjit Singh Jaijee, Dona Suri (2019). The Legacy of Militancy in Punjab: Long Road to 'Normalcy'. SAGE Publishing. p. 109. ISBN 978-93-5328-714-6.

- ^ "A life sentence". Hinduonnet.com. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ mha.nic.in Archived 11 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Times of India Illustrated Weekly. 1988. p. 30.

- ^ "1984 Sikh Pogrom: The First Day of November". Open The Magazine. 6 March 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ Ocala Star-Banner. Ocala Star-Banner.

- ^ Kaur, Jitinder (2000). Terrorism in the Tarai: A Socio-political Study. Ajanta Books International. p. 62. ISBN 978-81-202-0541-3.

- ^ "Punjab News | Breaking News | Latest Online News". Punjabnewsline.com. Archived from the original on 15 August 2010. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ Daily Report: Near East & South Asia, Volumes 95-250. 1995. p. 56.

- ^ "442 convicted in various anti-Sikh riots cases: Delhi Police". The Hindustan Times. 20 June 2012. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ "Apex court upholds life term for 3 in anti-Sikh riots". Deccan Herald. 9 April 2013. Archived from the original on 29 April 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ "Sajjan Kumar acquitted in anti-Sikh riots case". The Hindu. 30 April 2013. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ The Hindu Bureau (20 September 2023). "Ex-Congress MP Sajjan Kumar acquitted in 1984 anti-Sikh riots case". The Hindu. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ "Police didn't help victims". The Tribune. India. Archived from the original on 23 September 2009. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ^ Justice Denied, People's Union for Civil Liberties and People's Union for Democratic Right, 1987

- ^ "World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - India : Sikhs".

- ^ a b c d "Leaders 'incited' anti-Sikh riots". BBC. 8 August 2005. Archived from the original on 4 November 2009. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ Riots, India Justice Nanavati Commission of Inquiry, 1984 Anti-Sikh (2005). Justice Nanavati Commission of Inquiry (1984 Anti-Sikh Riots): Report. Ministry of Home Affairs. p. 131.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Fresh probe into India politician". BBC News. 18 December 2007. Archived from the original on 19 December 2007. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ^ "The Tribune, Chandigarh, India – Main News". The Tribune. India. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ^ "BJP to govt: Clear stand on anti-Sikh riots' witness". The Times of India. 30 November 2007. Archived from the original on 16 May 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ^ "1984 riots: CBI to re-investigate Tytler's role". The Times of India. 18 December 2007. Archived from the original on 16 May 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ^ "Anti Sikh riots witness to give statement to CBI in US". Ibnlive.in.com. Archived from the original on 24 December 2008. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ^ "CBI gives Tytler clean chit in 1984 riots case". The Indian Express. India. 3 April 2009. Archived from the original on 26 May 2009. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ^ Rai, Shambhavi; Malik, Devika (8 April 2009). "Jarnail Singh: Profile of a shoe thrower". IBN Live. Archived from the original on 11 April 2009.

- ^ Smriti Singh (9 April 2009). "Sikhs protest outside court hearing Tytler case". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ^ "Anti-Sikh riots case against Jagdish Tytler reopened". Archived from the original on 10 April 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- ^ "1984 anti-Sikh riots: Witness Abhishek Verma agrees to undergo polygraph test". The Hindustan Times. 26 July 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ ANI (29 October 2017). "1984 Anti-Sikh riots: Abhishek Verma receives 'death threats', files writ complaint with Police". Business Standard India. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ "Provide Security To 1984 Anti-Sikh Riots Witness: High Court To Cops". NDTV.com. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ "US court summons Congress party on Sikh riots case". Sify. 2 March 2011. Archived from the original on 5 March 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ "US court to hear 1984 anti-Sikh riots case on March 29 as Congress hires US law firm to defend itself". The Times of India. 16 March 2012. Archived from the original on 9 September 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ "U.S. court issues summons to Congress for anti-Sikh riots". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 2 March 2011. Archived from the original on 5 March 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ Singh, Yoshita (16 March 2012). "'84 Riots: US Court Dismisses Complaint Against Nath". Outlook India. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ "US court dismisses plea against Nath in anti-Sikh riots case". Deccan Herald. 16 March 2012.

- ^ "New York Court summons Sonia Gandhi in 1984 Sikh Riots Case". Archived from the original on 8 September 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ "US court give relief to Sonia Gandhi in Sikh riots case". Patrika Group. 11 July 2014. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ^ "Cobrapost Sting: Government didn't allow police to act in 1984 riots". news.biharprabha.com. Indo-Asian News Service. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ Rajagopal, Krishnadas (10 January 2018). "Supreme Court to form its own special team to probe 186 anti-Sikh riots cases". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ "Amritsar 'genocide' commemoration: Sikhs march through London". BBC News. 8 June 2014.

- ^ Rana, Yudhvir (16 July 2010). "Sikh clergy: 1984 riots 'genocide'". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ "Canadian Sikh MP distances himself from riots petition". The Indian Express. 17 June 2010. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ Singh, IP (11 May 2019). "PM Modi slams Pitroda's remark, calls 1984 riots a 'horrendous genocide'". Times of India.

- ^ "US house resolution introduced to formally recognise, commemorate Sikh genocide of 1984". Deccan Herald. 25 October 2024.

- ^ "California assembly describes 1984 riots as 'genocide'". The Times of India. Press Trust of India. 22 April 2015. Archived from the original on 6 September 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ "Bill Text". ca.gov. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ "An Act Designating Various Days and Weeks". Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ "NDP remembers the 1984 Sikh Genocide on its 40th anniversary". New Democratic Party.

- ^ "Canadians have a right to be 'concerned' about 1984 Sikh massacre, Harjit Sajjan says". CBC News. Archived from the original on 19 April 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ "Flag Raisings and Half-Mastings". City of Brampton.

- ^ "Call To Recognise Sikh Killings As Genocide". Sky News. 1 November 2012.

- ^ "PM apologises for 84 anti-Sikh riots". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 9 May 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ Suroor, Hasan (21 April 2011). "Manmohan Singh's apology for anti-Sikh riots a 'Gandhian moment of moral clarity,' says 2005 cable". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ^ Nanavati (1 June 2010). "Nanavati Report". Nanavati commission. Archived from the original on 12 May 2010. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- ^ BSSF (1 June 2010). "Remembrance March in London". British Sikh Student Federation. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- ^ Naithani, Shobhita (25 April 2009). "'I Lived As A Queen. Now, I'm A Servant'". Tehelka. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ Pandit, Ambika (1 November 2016). "'Wall of truth' to tell you 1984 riots' story by Nov-end". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ "'Wall of Truth' to have names of all Sikhs killed in hate crimes: DSGMC". The Hindustan Times. 10 July 2018. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ "Bilkis Bano: 'I Want Justice, Not Revenge, I Want My Daughters to Grow Up in a Safe India'". The Wire. 8 May 2017. Archived from the original on 9 May 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

Further reading

- Pav Singh. 1984 India's Guilty Secret. (Rupa & Kashi House 2017).

- Rao, Amiya; Ghose, Aurobindo; Pancholi, N. D. (1985). Truth about Delhi violence: report to the nation. India: Citizens for Democracy. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- Kaur, Jaskaran; Crossette, Barbara (2006). Twenty years of impunity: the November 1984 pogroms of Sikhs in India (PDF) (2nd ed.). Portland, OR: Ensaaf. ISBN 978-0-9787073-0-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- Cynthia Keppley Mahmood. Fighting for Faith and Nation: Dialogues With Sikh Militants. University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 978-0-8122-1592-2.

- Ram Narayan Kumar et al. Reduced to Ashes: The Insurgency and Human Rights in Punjab.South Asia Forum for Human Rights, 2003. Archived from the on 12 July 2003.

- Joyce Pettigrew. The Sikhs of the Punjab: Unheard Voices of State and Guerrilla Violence. Zed Books Ltd., 1995.

- Anurag Singh. Giani Kirpal Singh's Eye-Witness Account of Operation Bluestar. 1999.

- Patwant Singh. The Sikhs. New York: Knopf, 2000.

- Harnik Deol. Religion and Nationalism in India: The Case of the Punjab. London: Routledge, 2000

- Mark Tully. Amritsar: Mrs Gandhi's Last Battle. ISBN 978-0-224-02328-3.

- Ranbir Singh Sandhu. Struggle for Justice: Speeches and Conversations of Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale. Ohio: SERF, 1999.

- Iqbal Singh. Punjab Under Siege: A Critical Analysis. New York: Allen, McMillan and Enderson, 1986.

- Paul Brass. Language, Religion and Politics in North India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1974.

- PUCL report "Who Are The Guilty." Link to report.

- Manoj Mitta & H.S. Phoolka. When a Tree Shook Delhi (Roli Books, 2007), ISBN 978-81-7436-598-9.

- Jarnail Singh, 'I Accuse...' (Penguin Books India, 2009), ISBN 978-0-670-08394-7

- Jyoti Grewal, 'Betrayed by the state: the anti-Sikh pogrom of 1984' (Penguin Books India, 2007), ISBN 978-0-14-306303-2

External links

- 1984 Anti-Sikh Riots Homepage Archived 21 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine at Times of India

- 1984 riots case records, Government of Delhi

- Misra Commission Report

- Ahooja Committee Report

- Who Are The Guilty?

- In pictures: Massacre of the Sikhs

- 1984 anti-Sikh riots

- 1980s in Delhi

- 1984 murders in India

- 20th-century mass murder in India

- Assassination of Indira Gandhi

- Attacks on religious buildings and structures in India

- History of the Indian National Congress

- Sexual violence at riots and crowd disturbances

- History of Delhi (1947–present)

- 1980s in Punjab, India

- Religious riots in India

- Ethnic cleansing

- Ethnic cleansing in Asia

- Massacres in India

- Massacres in 1984

- Massacres of Sikhs

- October 1984 events in Asia

- November 1984 events in Asia

- Attacks on buildings and structures in 1984

- Pogroms

- Persecution of Sikhs

- Genocides in Asia