Anthony the Great: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

Anthony went to the [[Al Fayyum|Fayyum]] and confirmed the brethren there in the [[Christian]] faith, then returned to his old Roman fort. In 311, Anthony wished to become a [[martyr]] and went to [[Alexandria]]. He visited those who were imprisoned for the sake of [[Christ]] and comforted them. When the Governor saw that he was confessing his [[Christianity]] publicly, not caring what might happen to him, he ordered him not to show up in the city. However, the Saint did not heed his threats. He faced him and argued with him in order that he might arouse his anger so that he might be tortured and martyred, but it did not happen. |

Anthony went to the [[Al Fayyum|Fayyum]] and confirmed the brethren there in the [[Christian]] faith, then returned to his old Roman fort. In 311, Anthony wished to become a [[martyr]] and went to [[Alexandria]]. He visited those who were imprisoned for the sake of [[Christ]] and comforted them. When the Governor saw that he was confessing his [[Christianity]] publicly, not caring what might happen to him, he ordered him not to show up in the city. However, the Saint did not heed his threats. He faced him and argued with him in order that he might arouse his anger so that he might be tortured and martyred, but it did not happen. |

||

He left Alexandria to return to the old Roman fort upon the end of the persecutions. Here, many came to visit him and to hear his teachings. He saw that these visits kept him away from his worship. As a result, he went further into the [[Eastern Desert]] of [[Egypt]]. He travelled to the inner wilderness for three days, until he found a spring of water and some palm trees, and then he chose to settle there. On this spot now stands the monastery of Saint Anthony the Great. There, he anticipated the rule of [[Benedict of Nursia]] who lived about 200 years later; "pray and work", by engaging himself and his disciple or disciples in manual labor. Anthony himself cultivated a garden and wove mats of [[juncus|rushes]]. He and his disciples were regularly sought out for words of enlightenment. These statements were later collected into the book of ''[[Sayings of the Desert Fathers]]''. Anthony himself is said to have spoken to those of a spiritual disposition personally, leaving the task of addressing the more worldly visitors to [[Macarius of Alexandria|Macarius]]. On occasions, he would go to the monastery on the outskirts of the desert by the [[Nile]] to visit the brethren, then return to his inner [[monastery]]. |

He left Alexandria to return to the old Roman fort upon the end of the persecutions. Here, many came to visit him and to hear his teachings. He saw that these visits kept him away from his worship. As a result, he went further into the [[Eastern Desert]] of [[Egypt]]. He travelled to the inner wilderness for three days, until he found a spring of water and some palm trees, and then he chose to settle there. On this spot now stands the monastery of Saint Anthony the Great. There, he anticipated the rule of [[Benedict of Nursia]] who lived about 200 years later; "pray and work", and also placed his sister in a "house of virgins", because he didnt want her to be taken advantage of by a 40 year old smelly man who doesnt like my pink lemonade. By engaging himself and his disciple or disciples in manual labor. Anthony himself cultivated a garden and wove mats of [[juncus|rushes]]. He and his disciples were regularly sought out for words of enlightenment. These statements were later collected into the book of ''[[Sayings of the Desert Fathers]]''. Anthony himself is said to have spoken to those of a spiritual disposition personally, leaving the task of addressing the more worldly visitors to [[Macarius of Alexandria|Macarius]]. On occasions, he would go to the monastery on the outskirts of the desert by the [[Nile]] to visit the brethren, then return to his inner [[monastery]]. |

||

The backstory of one of the surviving epistles, directed to [[Constantine I (emperor)|Constantine I]], recounts how the fame of Saint Anthony spread abroad and reached Emperor Constantine. The Emperor wrote to him offering him praise and asking him to pray for him. The brethren were pleased with the Emperor's letter, but Anthony did not pay any attention to it, and he said to them, "The books of God, the King of Kings and the Lord of Lords, commands us every day, but we do not heed what they tell us, and we turn our backs on them." Under the persistence of the brethren who told him, "Emperor Constantine loves the church," he accepted to write him a letter blessing him, and praying for the peace and safety of the empire and the church. |

The backstory of one of the surviving epistles, directed to [[Constantine I (emperor)|Constantine I]], recounts how the fame of Saint Anthony spread abroad and reached Emperor Constantine. The Emperor wrote to him offering him praise and asking him to pray for him. The brethren were pleased with the Emperor's letter, but Anthony did not pay any attention to it, and he said to them, "The books of God, the King of Kings and the Lord of Lords, commands us every day, but we do not heed what they tell us, and we turn our backs on them." Under the persistence of the brethren who told him, "Emperor Constantine loves the church," he accepted to write him a letter blessing him, and praying for the peace and safety of the empire and the church. |

||

Revision as of 13:24, 19 May 2011

Saint Anthony of the Deserts | |

|---|---|

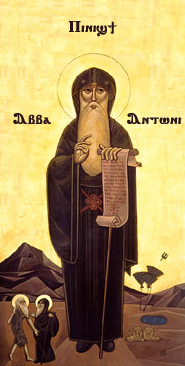

A Coptic icon, showing at left Anthony with Paul of Thebes | |

| Venerable and God-bearing Father | |

| Born | ca.251 Herakleopolis Magna, Egypt |

| Died | 356 Mount Colzim, Egypt |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodoxy, Coptic Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy |

| Major shrine | Monastery of Saint Anthony, Egypt Saint-Antoine-l'Abbaye, France |

| Feast | January 17 (Western Christianity and Eastern Orthodoxy) January 30 = Tobi 22 (Coptic Church) |

| Attributes | bell; pig; book; Cross of Tau[1][2] |

| Patronage | Basket makers, brushmakers, gravediggers[3] |

Anthony the Great or Antony the Great (c. 251–356), (Coptic Ⲁⲃⲃⲁ Ⲁⲛⲧⲱⲛⲓ), also known as Saint Anthony, Anthony the Abbot, Anthony of Egypt, Anthony of the Desert, Anthony the Anchorite, Abba Antonius (Ἀββᾶς Ἀντώνιος), and Father of All Monks, was a Christian saint from Egypt, a prominent leader among the Desert Fathers. He is celebrated in many churches on his feast days: 17 January in the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church; and (January 30) in the Coptic Orthodox Church, the Coptic Catholic Church and the Russian Orthodox Church

The biography of Anthony's life by Athanasius of Alexandria helped to spread the concept of monasticism, particularly in Western Europe through Latin translations. He is often erroneously considered the first monk, but as his biography and other sources make clear, there were many ascetics before him. Anthony was, however, the first known ascetic going into the wilderness, a geographical shift that seems to have contributed to his renown.[4]

Anthony is appealed to against infectious diseases, particularly skin diseases. "Saint Anthony's fire" has described different afflictions including ergotism, erysipelas and shingles.

Life

Most of what is known about the life of Anthony comes from the Life of Anthony. Written in Greek around 360 by Athanasius of Alexandria. It depicts Anthony as an illiterate and holy man who through his existence in a primordial landscape has an absolute connection to the divine truth, which always is synonymous with that of Athanasius as the biographer.[4] Sometime before 374, it was translated into Latin by Evagrius of Antioch. The Latin translation helped the Life become one of the best known works of literature in the Christian world, a status it would hold through the Middle Ages.[5] In addition to the Life, several surviving homilies and epistles of varying authenticity provide some additional autobiographical detail.

Anthony was born in Cooma near Herakleopolis Magna in Lower Egypt in 251 to wealthy landowner parents. When he was about 18 years old, his parents died and left him with the care of his unmarried sister.

There are various legends associating him with pigs: one is that for a time he worked as a swineherd.[1][2][3]

In 285, at the age of 34, he decided to follow the words of Jesus, who had said: "If you want to be perfect, go, sell what you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasures in heaven; and come, follow Me.",[6] which is part of the Evangelical counsels. Taking these words quite literally, Anthony gave away some of the family estate to his neighbors, sold the remaining property, donated the funds thus raised to the poor, placed his sister with a group of Christian virgins,[7] a sort of proto-nunnery at the time, and himself became the disciple of a local hermit.[8]

The appellation "Father of Monasticism" is misleading, as Christian monasticism was already being practiced in the deserts of Egypt. Ascetics commonly retired to isolated locations on the outskirts of cities. Anthony is notable for being one of the first ascetics to attempt living in the desert proper, completely cut off from civilization. His anchoretic lifestyle was remarkably harsher than that of his predecessors. By the 2nd century there were also famous Christian ascetics, such as Saint Thecla. Saint Anthony decided to follow this tradition and headed out into the alkaline desert region called Nitria in Latin (Wadi El Natrun today), about 95 km (59 mi) west of Alexandria, some of the most rugged terrain of the Western Desert. Here he remained for some 13 years.[8]

Also note that the Therapeutae, pagan ascetic hermits and loosely organized cenobitic communities described by the Hellenized Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria in the first century, were long established in the harsh environments by the Lake Mareotis close to Alexandria, and in other less-accessible regions. Philo understood that for "this class of persons may be met with in many places, for both Greece and barbarian countries want to enjoy whatever is perfectly good."[9]

According to Athanasius, the devil fought St. Anthony by afflicting him with boredom, laziness, and the phantoms of women, which he overcame by the power of prayer, providing a theme for Christian art. After that, he moved to a tomb, where he resided and closed the door on himself, depending on some local villagers who brought him food. When the devil perceived his ascetic life and his intense worship, he was envious and beat him mercilessly, leaving him unconscious. When his friends from the local village came to visit him and found him in this condition, they carried him to a church.

After he recovered, he made a second effort and went back into the desert to a farther mountain by the Nile called Pispir, now Der el Memun, opposite Crocodilopolis. There he lived strictly enclosed in an old abandoned Roman fort for some twenty years.[8] According to Athanasius, the devil again resumed his war against Saint Anthony, only this time the phantoms were in the form of wild beasts, wolves, lions, snakes and scorpions. They appeared as if they were about to attack him or cut him into pieces. But the saint would laugh at them scornfully and say, "If any of you have any authority over me, only one would have been sufficient to fight me." At his saying this, they disappeared as though in smoke, and God gave him the victory over the devil. While in the fort he only communicated with the outside world by a crevice through which food would be passed and he would say a few words. Saint Anthony would prepare a quantity of bread that would sustain him for six months. He did not allow anyone to enter his cell; whoever came to him stood outside and listened to his advice.

Then one day he emerged from the fort with the help of villagers to break down the door. By this time most had expected him to have wasted away, or gone insane in his solitary confinement, but he emerged healthy, serene, and enlightened. Everyone was amazed that he had been through these trials and emerged spiritually rejuvenated. He was hailed as a hero and from this time forth the legend of Anthony began to spread and grow.

Anthony went to the Fayyum and confirmed the brethren there in the Christian faith, then returned to his old Roman fort. In 311, Anthony wished to become a martyr and went to Alexandria. He visited those who were imprisoned for the sake of Christ and comforted them. When the Governor saw that he was confessing his Christianity publicly, not caring what might happen to him, he ordered him not to show up in the city. However, the Saint did not heed his threats. He faced him and argued with him in order that he might arouse his anger so that he might be tortured and martyred, but it did not happen.

He left Alexandria to return to the old Roman fort upon the end of the persecutions. Here, many came to visit him and to hear his teachings. He saw that these visits kept him away from his worship. As a result, he went further into the Eastern Desert of Egypt. He travelled to the inner wilderness for three days, until he found a spring of water and some palm trees, and then he chose to settle there. On this spot now stands the monastery of Saint Anthony the Great. There, he anticipated the rule of Benedict of Nursia who lived about 200 years later; "pray and work", and also placed his sister in a "house of virgins", because he didnt want her to be taken advantage of by a 40 year old smelly man who doesnt like my pink lemonade. By engaging himself and his disciple or disciples in manual labor. Anthony himself cultivated a garden and wove mats of rushes. He and his disciples were regularly sought out for words of enlightenment. These statements were later collected into the book of Sayings of the Desert Fathers. Anthony himself is said to have spoken to those of a spiritual disposition personally, leaving the task of addressing the more worldly visitors to Macarius. On occasions, he would go to the monastery on the outskirts of the desert by the Nile to visit the brethren, then return to his inner monastery.

The backstory of one of the surviving epistles, directed to Constantine I, recounts how the fame of Saint Anthony spread abroad and reached Emperor Constantine. The Emperor wrote to him offering him praise and asking him to pray for him. The brethren were pleased with the Emperor's letter, but Anthony did not pay any attention to it, and he said to them, "The books of God, the King of Kings and the Lord of Lords, commands us every day, but we do not heed what they tell us, and we turn our backs on them." Under the persistence of the brethren who told him, "Emperor Constantine loves the church," he accepted to write him a letter blessing him, and praying for the peace and safety of the empire and the church.

According to Athanasius, Saint Anthony heard a voice telling him, "Go out and see." He went out and saw an angel who wore a girdle with a cross, one resembling the holy Eskiem (Tonsure or Schema), and on his head was a head cover (Kolansowa). He was sitting while braiding palm leaves, then he stood up to pray, and again he sat to weave. A voice came to him saying, "Anthony, do this and you will rest." Henceforth, he started to wear this tunic that he saw, and began to weave palm leaves, and never got bored again. Saint Anthony prophesied about the persecution that was about to happen to the church and the control of the heretics over it, the church victory and its return to its formal glory, and the end of the age. When Saint Macarius visited Saint Anthony, Saint Anthony clothed him with the monk's garb, and foretold him what would be of him. When the day drew near of the departure of Saint Paul the First Hermit in the desert, Saint Anthony went to him and buried him, after clothing him in a tunic which was a present from St Athanasius the Apostolic, the 20th Patriarch of Alexandria.

In 338, he was summoned by Athanasius of Alexandria to help refute the teachings of Arius.[8]

Final days

When Saint Anthony felt that the day of his departure had approached, he commanded his disciples to give his staff to Saint Macarius, and to give one sheepskin cloak to Saint Athanasius and the other sheepskin cloak to Saint Serapion, his disciple. He further instructed his disciples to bury his body in an unmarked, secret grave, lest the Egyptians divide his body in pieces, as was the custom in Egypt.[citation needed] He stretched himself on the ground and gave up his spirit. Saint Anthony the Great lived for 105 years and departed on the year 356.

He probably spoke only his native language, Coptic, but his sayings were spread in a Greek translation. He himself left no writings. His biography was written by Saint Athanasius and titled Life of Saint Anthony the Great. Many stories are also told about him in various collections of sayings of the Desert Fathers.

Though Anthony himself did not organize or create a monastery, a community grew around him based on his example of living an ascetic and isolated life. Athanasius' biography helped propagate Anthony's ideals. Athanasius writes, "For monks, the life of Anthony is a sufficient example of asceticism."[8]

Temptation

Famously, Anthony is said to have faced a series of supernatural temptations during his pilgrimage to the desert. The first to report on the temptation was his contemporary Athanasius of Alexandria. However, some modern scholars have argued that the demons and temptations that Anthony is reported to have faced may have been related to Athanasius by some of the simpler pilgrims who had visited him, who may have been conveying what they had been told in a manner more dramatic than it had been conveyed to them.[citation needed] It is possible these events, like the paintings, are full of rich metaphor or in the case of the animals of the desert, perhaps a vision or dream. Some of the stories included in Saint Anthony's biography are perpetuated now mostly in paintings, where they give an opportunity for artists to depict their more lurid or bizarre interpretations. Many artists, including Martin Schongauer, Hieronymus Bosch, Max Ernst, and Salvador Dalí, have depicted these incidents from the life of Anthony; in prose, the tale was retold and embellished by Gustave Flaubert in The Temptation of Saint Anthony. Emphasis on these stories, however, did not really begin until the Middle Ages, when the psychology of the individual became of greater interest.[8] Below are some of these controversial tales.

The satyr and the centaur

Saint Anthony was on a journey in the desert to find his predecessor, Saint Paul of Thebes. Saint Anthony had been under the impression that he was the first person to ever dwell in the desert; however, due to a vision, Saint Anthony was called into the desert to find his predecessor, Saint Paul. On his way there he ran into two demons in the forms of a centaur and a satyr. Many works of art depict Saint Anthony meeting with this centaur and satyr. Western theology considers these demons to have been temptations. At any rate, he was stopped by these demons and asked, "Who are you?" To that the satyr replied, "I am a mortal, one of those whom the gentiles call Fauns, Satyrs and Incubi, I am on a mission from my flock. We request thee to pray for us unto the common God, whom ye know to have come for the salvation of the world, and whose praise is sounded all over the earth." Rejoicing at the glory of Christ, St. Anthony, turning his face towards Alexandria... In the end, the centaur showed Saint Anthony the way to his destination.[10]

Silver and gold

Another time Saint Anthony was traveling in the desert he found a plate of silver coins in his path. He pondered for a moment as to why a plate of silver coins would be out in the desert where no one else travels. Then he realized the devil must have laid it out there to tempt him. To that he said, "Ha! Devil, thou weenest to tempt me and deceive me, but it shall not be in thy power." Once he said this, the plate of silver vanished. Saint Anthony continued walking along and saw a pile of gold in his way which the devil had laid there to deceive him. Saint Anthony cast the pile of gold into a fire, and it vanished just like the silver coins did. After these events, Saint Anthony had a vision where the whole world was full of snares and traps. He cried to the Lord, "Oh good Lord, who may escape from these snares?" A voice said back to him, "humility shall escape them without more. "

Demons in the cave

One time Saint Anthony tried hiding in a cave to escape the demons that plagued him. There were so many little demons in the cave though that Saint Anthony's servant had to carry him out because they had beaten him to death. When the hermits were gathered to Saint Anthony's corpse to mourn his death, Saint Anthony was revived. He demanded that his servants take him back to that cave where the demons had beaten him. When he got there he called out to the demons, and they came back as wild beasts to rip him to shreds. All of a sudden a bright light flashed, and the demons ran away. Saint Anthony knew that the light must have come from God, and he asked God where was he before when the demons attacked him. God replied, "I was here but I would see and abide to see thy battle, and because thou hast manly fought and well maintained thy battle, I shall make thy name to be spread through all the world."[11]

Veneration

He was secretly buried on the mountain-top where he had chosen to live. His remains were reportedly discovered in 361, and transferred to Alexandria. Some time later, they were taken from Alexandria to Constantinople, so that they might escape the destruction being perpetrated by invading Saracens. Later, in the eleventh century, the emperor gave them to the French count Jocelin. Jocelin had them transferred to La-Motte-Saint-Didier, which was then renamed Saint-Antoine-en-Dauphiné.[8] There, Anthony is credited with assisting in a number of miraculous healings, primarily from ergotism, which became known as "St. Anthony's Fire". He was credited by two local noblemen of assisting them in recovery from the disease. They then founded the Hospital Brothers of St. Anthony in honour of him.[8] Veneration of Anthony in the East is more restrained. There are comparatively few icons and paintings of him. He is regarded as the "first master of the desert and the pinnacle of holy monks", however, and there are monastic communities of the Maronite, Chaldean, and Orthodox churches which state that they follow his monastic rule.[8] During the Middle Ages, Anthony, along with Quirinus of Neuss, Cornelius and Hubertus, was venerated as one of the Four Holy Marshals (Vier Marschälle Gottes) in the Rhineland.[12][13] [14]

Coptic literature

Examples of purely Coptic literature are the works of Saint Anthony and Saint Pachomius, who only spoke Coptic, and the sermons and preachings of Saint Shenouda the Archmandrite, who chose to only write in Coptic. Saint Shenouda was a popular leader who only spoke to the Egyptians in Egyptian language (Coptic), the language of the repressed, not in Greek, the language of the rulers.

The earliest original writings in Coptic language were the letters by Saint Anthony. During the 3rd and 4th centuries many ecclesiastics and monks wrote in Coptic.[15]

See also

- Coptic Saints

- Hermit

- Monastery of Saint Anthony, Egypt

- Patron saints of ailments, illness and dangers

- Poustinia

- The Temptation of St. Anthony

- St. Anthony Hall

Notes

- ^ Tresidder, Jack (2005). The complete dictionary of symbols. Chronicle Books. p. 36. ISBN 9780811847674.

- ^ Cornwell, Hilarie (2009). Saints, Signs, and Symbols: The Symbolic Language of Christian Art. Church Publishing. p. 23. ISBN 9780819223456. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Butler, Alban (1991). Michael J. Walsh (ed.). Butler's lives of the saints. HarperCollins. pp. 439–40. ISBN 9780060692995. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- ^ a b Dag Øistein Endsjø Primordial landscapes, incorruptible bodies. Desert asceticism and the Christian appropriation of Greek ideas on geography, bodies, and immortality. New York: Peter Lang 2008.

- ^ White, 4.

- ^ Mt 19:21

- ^ Athanasius of Alexandria, Life of Antony, 3. In Early Christian Lives, Carolinne White, trans. (London: Penguin Books, 1998), p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Burns, Paul, ed. Butler's Lives of the Saints:New Full Edition January vol. Collegeville, MN:The Liturgical Press. ISBN 0-8146-2377-8.

- ^ Philo,De vita contemplativa

- ^ St. Paul the Hermit, Catholic Encyclopedia

- ^ http://www.catholic-forum.com/saints/golden153.htm

- ^ Quirinus von Rom (von Neuss) - Ökumenisches Heiligenlexikon

- ^ marschaelle

- ^ Die Kapelle

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica

References

- Notes

- The Greek Vita of Athanasius. Ed. by G. J. M. Bartelink ('Vie d'Antoine'). Paris 2000. Sources Chrétiennes 400.

- The almost contemporary Latin translation: in Heribert Rosweyd, Vitae Patrum (Migne, Patrologia Latina. lxxiii.). New critical edition and study of this Latin translation: P.H.E. Bertrand, Die Evagriusübersetzung der Vita Antonii: Rezeption - Überlieferung - Edition. Unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Vitas Patrum-Tradition. Utrecht 2005 (dissertation) free available: [4]

- Accounts of St Anthony are given by Cardinal Newman ("Church of the Fathers" in Historical Sketches) and Alban Butler, Lives of the Saints (under Jan. 17).

- Burns, Paul, ed. Butler's Lives of the Saints: New Full Edition January vol. Collegeville, MN:The Liturgical Press. ISBN 0-8146-2377-8.

- A Hagiographic Account of the life of St. Anthony from the Coptic Church

Historical and critical

- Athanasius, Saint (1892). "The Life of Saint Antony". In Schaff, Phillip; Wace, Henry (eds.). Athanasius: Select Works and Letters. New York: C. Scribner's Sons.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapter= - E. C. Butler, (1898, 1904). Lausiac History of Palladius, Part I. pp. 197, 215-228; Part II. pp. ix.-xii. (See Palladius of Galatia).

- P.H.E. Bertrand, Die Evagriusübersetzung der Vita Antonii: Rezeption - Überlieferung - Edition. Unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Vitas Patrum-Tradition. Utrecht 2005. [dissertation] [free available: [5]

- Catholic Encyclopedia 1908: "St. Anthony the Great"

- Coptic Monastery of St Anthony the Great website

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

Texts attributed to St Anthony

- "Discourse on Demons", translated by Rev. H. Ellershaw (on-line)

- "Letter To Theodore", translated by Rev. Daniel and Esmeralda Jennings (on-line)

Further reading

- Barnes, T.D. 1986. Angel of Light or Mystic Initiate? The Problem of the Life of Antony in Journal of Theological Studies 37: 353-68.

- Chadwick, Henry (1993). The Early Church (Rev. ed. ed.). London: Penguin Books.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Dragas George Dion 2005. Saint Athanasius of Alexandria: Original Research and New Perspectives. Rollinsford: Orthodox Research Institute.

- Endsjø, Dag Øistein 2008. Primordial landscapes, incorruptible bodies. Desert asceticism and the Christian appropriation of Greek ideas on geography, bodies, and immortality. New York: Peter Lang 2008.

- Fülöp-Miller, René (1945). Gode, Alexander; Fülöp-Miller, Erika (eds.). The Saints That Moved the World, Anthony, Augustine, Francis, Ignatius, Theresa. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell.

- Kelsey, Neal 1992. The Body as Desert in The Life of St. Anthony in Semeia 57: 131-51.

- Louth, Andrew 1988. “St. Athanasius and the Greek Life of Antony” in Journal of Theological Studies 39: 504-9.

- Nigg, Walter (1959). Ilford, Mary (ed.). Warriors of God: The Great Religious Orders and Their Founders. London: Seeker and Warbmg.

- Pettersen, Alvyn 1989. “Athanasius' Presentation of Antony of the Desert's Admiration for his Body” in Studia Patristica 21: 438-47.

- Queffelec, Henri (1954). Whitall, James (ed.). Saint Anthony of the Desert. New York: E. P. Dutton.

- Reitzenstein, Richard 1914. Des Athanasius Werk über das Leben des Antonius: Ein philologischer Beitrag zur Geschichte des Mönchtums. *Heidelberg: Heidelberger Akad. der Wissenschaften.

- Roldanus J. 1993. “Origène, Antoine et Athanase: Leur interconnexion dans la Vie et les Lettres” in Studia Patristica 26: 389-414.

- Rubenson, Samuel (1995). The Letters of St. Antony: Monasticism and the Making of a Saint. Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

- Waddell, Helen (1936). The Desert Fathers. New York: Henry Holt.

- Ward, Maisie (1959). Saints Who Made History: The First Five Centuries. New York: Sheed and Ward.

- Williams, Michael A. 1982. “The Life of Antony and the Domestication of Charismatic Wisdom” in Journal of the American Academy of Religion Studies 48: 23-45.

- White, Carolinne (1998). Early Christian Lives. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-043526-9.

External links

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Video of church historian Andrew Walls who tells the story of Anthony

- Venerable and God-bearing Father Anthony the Great Orthodox icon and synaxarion

- Coptic vita of St. Anthony the Great

- 251 births

- 356 deaths

- Egyptian saints

- Egyptian hermits

- History of Catholic religious orders

- Catholic spirituality

- Eastern Orthodoxy

- Eastern Orthodox saints

- Eastern Catholic saints

- Roman Catholic saints

- Egyptian Roman Catholic saints

- People celebrated in the Lutheran liturgical calendar

- Christianity in Africa

- Egyptian centenarians

- Renewers of the church

- Egyptian Christian monks

- Christian monks

- 4th-century Christian saints

- Saints of the Golden Legend

- Anglican saints

- Oriental Orthodoxy

- Coptic Orthodox saints