Dāna

Dāna (Devanagari: दान, IAST: Dāna)[2] is a Sanskrit and Pali word that connotes the virtue of generosity, charity or giving of alms, in Indian religions and philosophies.[3][4]: 634–661

In Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism, dāna is the practice of cultivating generosity. It can take the form of giving to an individual in distress or need,[5] or of philanthropic public projects that empower and help many.[6]

Dāna is an ancient practice in Indian traditions, tracing back to Vedic traditions.[7][8]

Hinduism

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

Dāna (Sanskrit: दान) means giving, often in the context of donation and charity.[9] In other contexts, such as rituals, it can simply refer to the act of giving something.[9] Dāna is related to and mentioned in ancient texts along with concepts of Paropakāra (परोपकार) which means benevolent deed, helping others;[10] Dakshinā (दक्षिणा) which means fee one can afford;[11] and Bhikshā (भिक्षा), which means alms.[12]

Dāna is defined in traditional texts as any action of relinquishing the ownership of what one considered or identified as one's own, and investing the same in a recipient without expecting anything in return.[13]

While dāna is typically given to one person or family, Hinduism also discusses charity or giving aimed at public benefit, sometimes called utsarga. This aims at larger projects such as building a rest house, school, drinking water or irrigation well, planting trees, or building a care facility, among others.[14]: 54–62

Dāna in Hindu texts

[edit]The Rigveda has the earliest discussion of dāna in the Vedas.[15] The Rigveda relates it to satya "truth" and in another hymn points to the guilt one feels from not giving to those in need.[15] It uses da, the root of word dāna, in its hymns to refer to the act of giving to those in distress. Ralph T. H. Griffith, for example, translates Book 10, Hymn 117 of the Rig veda as follows:

The Gods have not ordained hunger to be our death: even to the well-fed man comes death in varied shape,

The riches of the liberal never waste away, while he who will not give finds none to comfort him,

The man with food in store who, when the needy comes in miserable case begging for bread to eat,

Hardens his heart against him, when of old finds not one to comfort him.

Bounteous is he who gives unto the beggar who comes to him in want of food, and the feeble,

Success attends him in the shout of battle. He makes a friend of him in future troubles,

No friend is he who to his friend and comrade who comes imploring food, will offer nothing.

Let the rich satisfy the poor implorer, and bend his eye upon a longer pathway,

Riches come now to one, now to another, and like the wheels of cars are ever rolling,

The foolish man wins food with fruitless labour: that food – I speak the truth – shall be his ruin,

He feeds no trusty friend, no man to love him. All guilt is he who eats with no partaker.

The Upanishads, composed before 500 BCE, present some of the earliest Upanishadic discussion of dāna. Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, in verse 5.2.3, states that three characteristics of a good, developed person are self-restraint (damah), compassion or love for all sentient life (daya), and charity (dāna).[17]

तदेतत्त्रयँ शिक्षेद् दमं दानं दयामिति[18]

Learn three cardinal virtues — self restraint, charity and compassion for all life.

Chandogya Upanishad, Book III, similarly, states that a virtuous life requires: tapas (asceticism), dāna (charity), arjava (straightforwardness), ahimsa (non-injury to all sentinent beings) and satyavacana (truthfulness).[17]

Bhagavad Gita describes the right and wrong forms of dāna in verses 17.20 through 17.22.[4]: 653–655 It defines sāttvikam (good, enlightened, pure) charity, in verse 17.20, as that given without expectation of return, at the proper time and place, and to a worthy person. It defines rajas (passion, ego driven, active) charity, in verse 17.21, as that given with the expectation of some return, or with a desire for fruits and results, or grudgingly. It defines tamas (ignorant, dark, destructive) charity, in verse 17.22, as that given with contempt, to unworthy person(s), at a wrong place and time. In Book 17, Bhadwad Gita suggests steadiness in sattvikam dāna, or the good form of charity is better; and that tamas should be avoided.[4]: 634–661 These three psychological categories are referred to as the guṇas in Hindu philosophy.[20]

The Adi Parva of the Hindu Epic Mahabharata, in Chapter 91, states that a person must first acquire wealth by honest means, then embark on charity; be hospitable to those who come to him; never inflict pain on any living being; and share a portion with others whatever he consumes.[21]: 3–4 In Chapter 87 of Adi Parva, it calls sweet speech and refusal to use harsh words or wrong others even if you have been wronged, as a form of charity. In the Vana Parva, Chapter 194, the Mahabharata recommends that one must, "conquer the mean by charity, the untruthful by truth, the wicked by forgiveness, and dishonesty by honesty".[22]: 6 Anushasana Parva in Chapter 58, recommends public projects as a form of dāna.[6] It discusses the building of drinking water tanks for people and cattle as a noble form of giving, as well as giving of lamps for lighting dark public spaces.[6] In later sections of Chapter 58, it describes planting public orchards, with trees that give fruits to strangers and shade to travelers, as meritorious acts of benevolent charity.[6] In Chapter 59 of Book 13 of the Mahabharata, Yudhishthira and Bhishma discuss the best and lasting gifts between people:

An assurance unto all creatures with love and affection and abstention from every kind of injury, acts of kindness and favor done to a person in distress, whatever gifts are made without the giver's ever thinking of them as gifts made by him, constitute, O chief of Bharata's race, the highest and best of gifts (dāna).

— The Mahabharata, XIII.59[5]

The Bhagavata Purana discusses when dāna is proper and when it is improper. In Book 8, Chapter 19, verse 36 it states that charity is inappropriate if it endangers and cripples modest livelihood of one's biological dependents or of one’s own. Charity from surplus income above that required for modest living is recommended in the Puranas.[14]: 43

Hindu texts exist in many Indian languages. For example, the Tirukkuṛaḷ, written between 200 BCE and 400 CE, is one of the most cherished classics on Hinduism written in a South Indian language. It discusses charity, dedicating Chapter 23 of Book 1 on Virtues to it.[23] Tirukkuṛaḷ suggests charity is necessary for a virtuous life and happiness. In it, Thiruvalluvar states in Chapter 23: "Giving to the poor is true charity, all other giving expects some return"; "Great, indeed, is the power to endure hunger. Greater still is the power to relieve other's hunger"; "Giving alms is a great reward in itself to one who gives".[23]: 47 In Chapter 101, he states: "Believing wealth is everything, yet giving away nothing, is a miserable state of mind"; "Vast wealth can be a curse to one who neither enjoys it nor gives to the worthy".[23]: 205 Like the Mahabharata, Tirukkuṛaḷ also extends the concept of charity to deeds (body), words (speech) and thoughts (mind). It states that a brightly beaming smile, the kindly light of loving eye, and saying pleasant words with sincere heart is a form of charity that every human being should strive to give.[23]: 21

Dāna in rituals

[edit]Dāna is also used to refer to rituals. For example, in a Hindu wedding, Dānakanyādāna (कन्यादान) refers to the ritual where a father gives his daughter's hand in marriage to the groom, after asking the groom to promise that he will never fail in his pursuit of dharma (moral and lawful life), artha (wealth) and kama (love). The groom promises to the bride's father, and repeats his promise three times in presence of all gathered as witness.[24]

Other types of charity includes donating means of economic activity and food source. For example, godāna (donation of a cow),[25] bhudāna (भूदान) (donation of land), and vidyādāna or jñānadāna (विद्यादान, ज्ञानदान): Sharing knowledge and teaching skills, aushadhādāna (औषधदान): Charity of care for the sick and diseased, abhayadāna (अभयदान): giving freedom from fear (asylum, protection to someone facing imminent injury), and anna dāna (अन्नादान): Giving food to the poor, needy and all visitors.[26]

The effect of dāna

[edit]Charity is held as a noble deed in Hinduism, to be done without expectation of any return from those who receive the charity.[13] Some texts reason, referring to the nature of social life, that charity is a form of good karma that affects one's future circumstances and environment, and that good charitable deeds lead to good future life because of the reciprocity principle.[13]

Living creatures get influenced through dānam,

Enemies lose hostility through dānam,

A stranger may become a loved one through dānam,

Vices are killed by dānam.— A Hindu Proverb, [13]: 365–366

Other Hindu texts, such as Vyasa Samhita, state that reciprocity may be innate in human nature and social functions but dāna is a virtue in itself, as doing good lifts the nature of one who gives.[27] The texts do not recommend charity to unworthy recipients or where charity may harm or encourage injury to or by the recipient. Dāna, thus, is a dharmic act, requires an idealistic-normative approach, and has spiritual and philosophical context.[13] The donor's intent and responsibility for diligence about the effect of dāna on the recipient is as important as the dāna itself. While the donor should not expect anything in return with dāna, the donor is expected to make an effort to determine the character of the recipient, and the likely return to the recipient and to the society.[13] Some medieval era authors state that dāna is best done with shraddha (faith), which is defined as being in good will, cheerful, welcoming the recipient of the charity and giving without anasuya (finding faults in the recipient).[28]: 196–197 These scholars of Hinduism, states Kohler,[specify] suggest that charity is most effective when it is done with delight, a sense of "unquestioning hospitality", where the dāna ignores the short term weaknesses as well as the circumstances of the recipient and takes a long term view.[28]: 196–197

In historical record

[edit]Xuanzang, the Chinese pilgrim to India, describes many Punya-śālās (houses of goodness, merit, charity) in his 7th-century CE memoir.[29][30] He mentions these Punyasalas and Dharmasalas in Takka (Punjab) and other north Indian places such as near the Deva temples of Haridwar at the mouth of river Ganges and eight Deva temples in Mulasthanapura. These, recorded Xuanzang, served the poor and the unfortunate, providing them food, clothing and medicine, also welcoming travelers and the destitute. So common were these, he wrote, that "travelers [like him] were never badly off."[29]

Al-Biruni, the Persian historian, who visited and lived in India for 16 years from about 1017 CE, mentions the practice of charity and almsgiving among Hindus as he observed during his stay. He wrote, "It is obligatory with them (Hindus) every day to give alms as much as possible."[8]

After the taxes, there are different opinions on how to spend their income. Some destine one-ninth of it for alms.[31] Others divide this income (after taxes) into four portions. One fourth is destined for common expenses, the second for liberal works of a noble mind, the third for alms, and the fourth for being kept in reserve.

— Abū Rayḥān al-Bīrūnī, Tarikh Al-Hind, 11th century CE[8]

Satrams, called Choultry, Dharamsala, or Chathrams in parts of India, have been one expression of Hindu charity. Satrams are shelters (rest houses) for travelers and the poor, with many serving water and free food. These were usually established along the roads connecting major Hindu temple sites in South Asia as well as near major temples.[32]

Hindu temples served as charitable institutions. Burton Stein[33] states that South Indian temples collected donations (melvarum) from devotees, during the Chola dynasty and Vijayanagara Empire periods in the 1st millennium through the first half of the 2nd millennium CE.[34] These dāna were then used to feed people in distress as well as fund public projects such as irrigation and land reclamation.[33][35]

Hindu treatises on dāna

[edit]Mitākṣarā by Vijñāneśvara is an 11th-century canonical discussion and commentary on dāna, composed under the patronage of Chalukya dynasty.[36]: 6 The discussion about charity is included in its thesis on ācāra (moral conduct).

Major Sanskrit treatises that discuss ethics, methods and rationale for charity and alms giving in Hinduism include, states Maria Heim,[36]: 4–5 the 12th-century Dāna Kānda "Book of Giving" by Laksmidhara of Kannauj, the 12th-century Dāna Sāgara "Sea of Giving" by Ballālasena of Bengal, and the 14th-century sub-book Dānakhanda in Caturvargacintamani "The Gem of the Four Aims of Human Life" by Hemadiri of Devagiri (modern Daulatabad, Maharashtra). The first two are few hundred page treatises each, while the third is over a thousand-page compendium on charity, from a region that is now part of modern-day eastern Maharashtra and Telangana; the text influenced Hindus of Deccan region and South India from 14th to 19th centuries.[36]: 4–5

Buddhism

[edit]

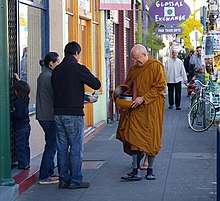

Dāna as a formal religious act is directed by the Buddhist laity specifically to a monastic or spiritually-developed person.[37] In Buddhist thought, it has the effect of purifying and transforming the mind of the giver.[38]

Generosity developed through giving leads to experience of material wealth and possibly being reborn in happy states. In the Pāli Canon's Dighajanu Sutta, generosity (denoted there by the Pāli word cāga, which can be synonymous with dāna) is identified as one of the four traits conditioning happiness and wealth in the next life. Conversely, lack of giving leads to unhappy states and poverty.

Dāna leads to one of the pāramitās or "perfections", the dānapāramitā. This can be characterized by unattached and unconditional generosity, giving and letting go.[citation needed]

Buddhists believe that giving without seeking anything in return leads to greater spiritual wealth. Moreover, it reduces the acquisitive impulses that ultimately lead to continued suffering[39] from egotism.

Dāna, or generosity, can be given in both material or immaterial ways. Spiritual giving—or the gift of noble teachings, known as dhamma-dāna, is said by the Buddha to surpass all other gifts. This type of generosity includes those who elucidate the Buddha’s teachings, such as monks who preach sermons or recite from the Tripiṭaka, teachers of meditation, unqualified persons who encourage others to keep precepts, or helping support teachers of meditation. The most common form of giving is in material gifts such as food, money, robes, and medicine.[40]

Jainism

[edit]Dāna is described as a virtue and duty in Jainism, just as it is in Buddhist texts and Hindu texts like Mitaksara and Vahni Purana.[36]: 47–49 It is considered an act of compassion, and must be done with no desire for material gain.[41] Four types of dāna are discussed in the texts of Jainism: Ahara-dana (donation of food), Ausadha-dana (donation of medicine), Jnana-dana (donation of knowledge) and Abhaya-dana (giving of protection or freedom from fear, asylum to someone under threat).[41] Dāna is one of ten means to gain positive karma in the soteriological theories of Jainism. Medieval era texts of Jainism dedicate a substantial portion of their discussions to the need and virtue of Dāna.[28]: 193–205 For example,Yashastilaka's book VIII section 43 is dedicated to the concept of dāna in Jainism.[42]

The practice of dāna is most commonly seen when lay people give alms to the monastic community. In Jainism, monks and nuns are not supposed to be involved in the process of making food and they also cannot purchase food since they cannot possess money. Therefore, dāna is important for the sustenance of the Jain monastic community. The lay donor also benefits from the act of dāna because "dāna is accepted as being a means of gaining merit and improving the quality of [their] destiny."[43]

Sikhism

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2015) |

Dāna, called Vand Chhako, is considered one of three duties of Sikhs.[44] The duty entails sharing part of one's earnings with others, by giving to charity and caring for others. Examples of dāna in Sikhism include selfless service and langar.[45]

See also

[edit]- Alms – Money or goods given to poor people

- Buddhist ethics – Ethics in Buddhism

- Buddhist economics – Buddhist philosophy on economics

- Charity (practice) – Voluntary giving of help to those in need

- Dīghajāṇu Sutta – Buddhist text about ethics for lay people

- Economic anthropology – Academic field

- Gift economy – Mode of exchange where valuables are given without rewards

- Merit (Buddhism) – Concept considered fundamental to Buddhist ethics

- Niyama – Recommended activities and habits in Yoga

- Offering (Buddhism) – Buddhist religious practice

- Pāramī – Buddhist qualities for spiritual perfection

- Philanthropy – Private efforts to increase public good

- Tulabhara – Ancient Indian practice in which a person is weighed against a commodity such as gold

- Vessantara Jātaka – Story of one of Gautama Buddha's past lives

- Virtue – Positive trait or quality deemed to be morally good

- Tithe – Religious donation

- Yavanarajya inscription – 1st century BCE inscription found near Mathura

- Zidqa – Alms in Mandaeism

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Jātaka, the Buddha's Past Birth-Stories, Level 1 Balustrade, Top, at Borobudur".

- ^ "Danam, Dānam: 1 definition". Wisdom Library. 2019-08-11. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ Cole, William Owen (1991). Moral Issues in Six Religions. Heinemann. pp. 104–105. ISBN 978-0435302993.

- ^ a b c Chapple, Christopher Key (19 March 2009). The Bhagavad Gita. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-1-4384-2842-0.

- ^ a b "Anusasana Parva". Mahabharata. Translated by Ganguli, Kisari Mohan. Calcutta: Bharata Press. 1893. LIX.

अभयं सर्वभूतेभ्यॊ वयसने चाप्य अनुग्रहम

यच चाभिलषितं दद्यात तृषितायाभियाचते

दत्तं मन्येत यद दत्त्वा तद दानं शरेष्ठम उच्यते

दत्तं दातारम अन्वेति यद दानं भरतर्षभ - ^ a b c d "Anusasana Parva". Mahabharata. Translated by Ganguli, Kisari Mohan. Calcutta: Bharata Press. 1893. LVIII.

- ^ Shah, Shashank; Ramamoorthy, V.E. (2013). Soulful Corporations: A Values-Based Perspective on Corporate Social Responsibility. Springer. p. 125. ISBN 978-81-322-1274-4.

The concept of Daana (charity) dates back to the Vedic period. The Rig Veda enjoins charity as a duty and responsibility of every citizen.

- ^ a b c Bīrūnī, Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad (1910). "LXVII: On Alms, and how a man must spend what he earns". Alberuni's India. Vol. 2. London: Kegan Paul, Trübner & Co. pp. 149–150.

- ^ a b "Spoken Sanskrit Dictionary: दान". University of Koeln, Germany. Archived from the original on 2014-12-14.

- ^

- "Spoken Sanskrit Dictionary: परोपकार". University of Koeln, Germany. Archived from the original on 2015-04-27.

- Marujo, Helena Águeda; Neto, Luis Miguel (16 August 2013). Positive Nations and Communities. Springer. p. 82. ISBN 978-94-007-6868-0.

- ^

- "Spoken Sanskrit Dictionary: दक्षिणा". University of Koeln, Germany. Archived from the original on 2015-04-27.

- Lochtefeld, James G. (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Vol. A–M. Rosen Publishing Group. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8.

- ^

- "Spoken Sanskrit Dictionary: bhikSA". University of Koeln, Germany. Archived from the original on 2015-04-27.

- Gomez, Alberto Garcia; Garcia, Alberto; Miranda, Gonzalo (2014). Religious Perspectives on Human Vulnerability in Bioethics. Springer. pp. 170–171. ISBN 978-94-017-8735-2.

- ^ a b c d e f Krishnan, Lilavati; Manoj, V.R. (2008). "Giving as a theme in the Indian psychology of values". In Rao, K. Ramakrishna; Paranjpe, A. C.; Dalal, Ajit K. (eds.). Handbook of Indian Psychology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 361–382. ISBN 978-81-7596-602-4.

- ^ a b Agarwal, Sanjay (2010). Daan and Other Giving Traditions in India. AccountAid India. ISBN 978-81-910854-0-2.

- ^ a b Hindery, R. "Comparative ethics in Hindu and Buddhist traditions". The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. 2 (1): 105.

- ^ The Rig Veda, Mandala 10, Hymn 117, Ralph T. H. Griffith (Translator)

- ^ a b c Kane, Pandurang Vaman (1941). "Samanya Dharma". History of Dharmasastra. Vol. 2, Part 1. Poona: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. p. 5.

- ^ "॥ बृहदारण्यकोपनिषत् ॥". sanskritdocuments.org. Archived from the original on 2014-12-14.

- ^ Brihadaranyaka Upanishad. Translated by Madhavananda, Swami. Advaita Ashrama. 1950. p. 816. For discussion: pages 814–821.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Bernard, Theos (1999). Hindu Philosophy. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 92–94. ISBN 978-81-208-1373-1.

- ^ "XCI: Sambhava Parva". Adi Parva. Translated by Dutt, M.N. Calcutta, Printed by H.C. Dass. 1895. p. 132.

- ^ "CXCIV: Markandeya Samasya Parva". Vana Parva. Translated by Dutt, M.N. Calcutta, Printed by H.C. Dass. 1895. p. 291.

- ^ a b c d Tiruvaḷḷuvar (1944). Tirukkuṛaḷ. Translated by Dikshitar, V.R. Ramachandra.

- ^

- Prabhu, Pandharinath H. (1991). Hindu Social Organization. Popular Prakashan. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-81-7154-206-2.

- Kane, P.V. (1974). History of Dharmasastra: Ancient and Medieval Civil Law in India. Vol. 2. Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. pp. 531–538.

- ^ Padma, Eṃ. Bi (1993). The Position of Women in Mediaeval Karnataka. Prasaranga: University of Mysore Press. p. 164.

- ^ Dubois, Abbe J.A. (1906). Hindu Manners, Customs and Ceremonies. Translated by Beauchamp, Henry K. Cosimo, Inc. pp. 223, 483–495.

- ^ The Dharam Shastra: Hindu Religious Codes. Vol. 3. Translated by Dutt, Manmatha Nath. New Delhi: Cosmo Publishers. 1979 [1906]. pp. 526–533.

- ^ a b c Heim, Maria (2007). "Dana as a Moral Category". In Bilimoria, P.; Prabhu, J.; Sharma, R. (eds.). Indian Ethics: Classical Traditions and Contemporary Challenges. Vol. 1. ISBN 978-0754633013.

- ^ a b Hiuen Tsiang (1906) [629]. Si-yu-ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World. Translated by Beal, Samuel. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, & Co. pp. 165–166 (Vol. 1), 198 (Vol. 1), 274–275 (Vol. 2).

- ^ Tan Chung (1970). "Ancient Indian Life Through Chinese Eyes". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 32: 137–149. JSTOR 44141059.

- ^ Al Biruni states that another one-ninth is put into savings/reserve, one-ninth in investment/trade for profits

- ^

- Kumari, Koutha Nirmala (1998). History of the Hindu Religious Endowments in Andhra Pradesh. Northern Book Centre. p. 128. ISBN 978-81-7211-085-7.

- Neelima, Kota (2012). Tirupati. Random House Publishers India. pp. 50–52. ISBN 978-81-8400-198-3.

- Reddy, Prabhavati C. (2014). Hindu Pilgrimage: Shifting Patterns of Worldview of Srisailam in South India. Routledge Hindu Studies. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-415-65997-0.

- Chakravarthy, Pradeep (June 27, 2010). "Sanctuaries of times past". The Hindu.

- ^ a b Stein, Burton (February 1960). "The Economic Function of a Medieval South Indian Temple". The Journal of Asian Studies. 19 (2): 163–76. doi:10.2307/2943547. JSTOR 2943547. S2CID 162283012.

- ^ Aiyangar, Sakkottai Krishnaswami (2004). Ancient India: Collected Essays on the Literary and Political History. Asian Educational Services. pp. 158–164. ISBN 978-81-206-1850-3.

- ^ Stein, Burton (February 4, 1961). "The state, the temple and agriculture development". The Economic Weekly Annual: 179–187.

- ^ a b c d Heim, Maria (1 June 2004). Theories of the Gift in South Asia: Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-203-50226-6.

- ^ Harvey, Peter (2013). An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices (2. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 267. ISBN 978-0-521-67674-8.

- ^ McFarlane, Stewart (2001). "The structure of Buddhist ethical teaching". In Harvey, Peter (ed.). Buddhism. New York: Continuum. p. 186. ISBN 0826453503.

- ^ Tsong-kha-pa (2002). Newland, Guy; Cutler, Joshua (eds.). The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment, Volume II. Translated by the Lamrim Chenmo Translation Committee. Canada: Snow Lion. pp. 236, 238. ISBN 1-55939-168-5.

- ^ Bikkhu Bodhi, ed. (1995). "Dana: The Practice of Giving". Access to Insight. Retrieved 2020-11-21.

- ^ a b Watts, Thomas D. (2006). "Charity". In Odekon, Mehmet (ed.). Encyclopedia of World Poverty. SAGE. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-4129-1807-7.

- ^ Singh, Ram Bhushan Prasad (2008) [1975]. Jainism in Early Medieval Karnataka. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 82. ISBN 978-81-208-3323-4.

- ^ Dundas, Paul (2002). The Jains. Library of religious beliefs and practices (2nd ed.). London; New York: Routledge. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-415-26605-5.

- ^ "Sikh Beliefs". BBC Religions. 2009-09-24.

- ^ Fleming, Marianne (2003). Thinking about God and Morality. Heinemann. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-435-30700-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Cantegreil, Mathieu; Chanana, Dweep; Kattumuri, Ruth, eds. (2013). Revealing Indian Philanthropy (PDF). Alliance Publishing Trust. ISBN 9781907376191. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-07-05. Retrieved 2023-07-05.

- Nath, Vijay (1987). Dāna, Gift System in Ancient India, c. 600 B.C.–c. A.D. 300: a socio-economic perspective. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. ISBN 978-81-215-0054-8.

- Singh, K.A.N. (September 2002). "Current Status of Philanthropy in India" (PDF).