Barnett Newman

Barnett Newman | |

|---|---|

Newman, c. 1969 | |

| Born | January 29, 1905 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | July 4, 1970 (aged 65) New York City, U.S. |

| Known for | Painting, sculpture |

| Notable work | Vir Heroicus Sublimis, The Stations of the Cross |

| Movement | Abstract expressionism, color field painting |

Barnett Newman (January 29, 1905 – July 4, 1970) was an American painter. He has been critically regarded as one of the major figures of abstract expressionism, and one of the foremost color field painters. His paintings explore the sense of place that viewers experience with art and incorporate the simplest forms to emphasize this feeling.[1]

Early life

[edit]Barnett Newman was born in New York City, the son of Jewish immigrants from Poland. He studied philosophy at the City College of New York and worked in his father's business manufacturing clothing. He later made a living as a teacher, writer, and critic.[2] From the 1930s, he made paintings, said to be in an expressionist style, but eventually destroyed all these works. Newman met Annalee Greenhouse in 1934 while both were working as substitute teachers at Grover Cleveland High School; they were married on June 30, 1936.[3]

Career

[edit]

What is the explanation of the seemingly insane drive of man to be painter and poet if it is not an act of defiance against man's fall and an assertion that he return to the Garden of Eden? For the artists are the first men.

— Barnett Newman [4]

Newman wrote catalogue forewords and reviews as well as organized exhibitions, He then became a member of the Uptown Group and had his first solo show at the Betty Parsons Gallery in 1948. Soon after his first exhibition, Newman remarked in one of the Artists' Session at Studio 35: "We are in the process of making the world, to a certain extent, in our own image."[5] Using his writing skills, Newman fought to reinforce his newly established image as an artist and to promote his work. An example is his letter on April 9, 1955, "Letter to Sidney Janis: ... it is true that Rothko talks the fighter. He fights, however, to submit to the philistine world. My struggle against bourgeois society has involved the total rejection of it."[6]

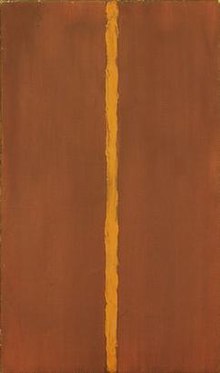

Throughout the 1940s, he worked in a surrealist vein, then developed his signature style.[7] This is characterized by areas of color separated by thin vertical lines, or "zips" as Newman called them. In the first works featuring zips, the color fields are variegated, but later the colors are pure and flat. Newman thought that he reached his fully distinct, signature style with the Onement series (from 1948). The zips define the spatial structure of the painting and simultaneously divide and unite the composition. According to art historian April Kingsley, the zip in Newman's paintings are 'flashing light of a nuclear explosion and the old testament pillar of fire', thus mixing the paradox of romantic sublime with the depiction of destruction and transcendence.[8] Already 1944 Barnett Newman tried to explain America's newest art movement and included a list of "the men in the new movement." Ex-surrealists, like Matta, are mentioned, and Wolfgang Paalen is mentioned twice with Gottlieb, Rothko, Pollock, Hofmann, Baziotes, Gorky and others. Motherwell is mentioned with a question mark.[9] The zip remained a constant feature of Newman's work throughout his life. In some paintings of the 1950s, such as The Wild, which is eight feet tall by one and a half inches wide (2.43 meters by 4.1 centimeters), the zip is all there is to the work. Newman also made a few sculptures which are essentially three-dimensional zips.[10]: 511

Although Newman's paintings appear to be purely abstract, and many of them were originally untitled, the names he later gave them hinted at specific subjects being addressed, often with a Jewish theme. Two paintings from the early 1950s, for example, are called Adam and Eve. There is also Uriel (1954), and Abraham (1949), a very dark painting which, as well as being the name of a biblical patriarch, was the name of Newman's father, who had died in 1947.

The Stations of the Cross series of black and white paintings (1958–1966), begun shortly after Newman had recovered from a heart attack, usually is regarded as the peak of his achievement. The series is subtitled Lema sabachthani - "Why have you forsaken me" - the last words spoken by Jesus on the cross, according to the New Testament. Newman saw these words as having universal significance in his own time. The series has been seen as a memorial to the victims of the Holocaust.[11]

Newman's late works, such as the Who's Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue series, use vibrant, pure colors, often on very large canvases - Anna's Light (1968), named in memory of his mother, who had died in 1965, is his largest work, 28 feet wide by 9 feet tall (8.5 by 2.7 meters). Newman also worked on shaped canvases late in life, with Chartres (1969), for example, being triangular, and returned to sculpture, making a small number of sleek pieces in steel. These later paintings are executed in acrylic paint rather than the oil paint of earlier pieces. Of his sculptures, Broken Obelisk (1963) is the most monumental and best-known, depicting an inverted obelisk whose point balances on the apex of a pyramid.

Newman also made a series of lithographs, the 18 Cantos (1963–64) which, according to Newman, are meant to be evocative of music. He also made a small number of etchings.

In 1948, Newman, William Baziotes, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell and David Hare founded the Subjects of the Artist School at 35 East 8th Street. These Well-attended lectures were open to the public, with speakers such as Jean Arp, John Cage and Ad Reinhardt, but the art school failed financially and closed in the spring of 1949.[12][13][14] Newman generally is classified as an abstract expressionist because his working in New York City in the 1950s, associating with other artists of the group and developing an abstract style which owed little or nothing to European art. However, his rejection of the expressive brushwork employed by other abstract expressionists, such as Clyfford Still and Mark Rothko, and his use of hard-edged areas of flat color, can be seen as a precursor to post painterly abstraction and the minimalist works of artists such as Frank Stella.

Newman was unappreciated as an artist for much of his life, being overlooked in favor of more colorful characters such as Jackson Pollock. The influential critic Clement Greenberg wrote enthusiastically about him, but it was not until the end of his life that he began to be taken seriously. He was, however, an important influence on many younger artists such as Donald Judd, Frank Stella and Bob Law.[10]: 512

Legacy

[edit]Newman died on July 4, 1970, aged 65, of a heart attack, in New York City.[2]

Nine years after Newman's death, his widow Annalee founded the Barnett Newman Foundation. The foundation functions as his official estate and serves "to encourage the study and understanding of Barnett Newman's life and works."[15] The foundation was instrumental in creating Newman's catalogue raisonné in 2004.[16] The U.S. copyright representative for the Barnett Newman Foundation is the Artists Rights Society.[17]

In 2018, the Foundation gave more than 70 artworks to the Jewish Museum, New York.[18]

Selected collections

[edit]Several public collections hold works by Barnett Newman. These include:

- Addison Gallery of American Art (Andover, Massachusetts)

- Allen Memorial Art Museum (Oberlin College, Ohio)

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Berlin State Museums

- Cleveland Museum of Art

- Detroit Institute of Art

- Harvard University Art Museums

- Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden (Washington D.C.)

- Indianapolis Museum of Art

- Kawamura Memorial Museum of Art (Japan)

- Kunstmuseum Basel (Switzerland)

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- Menil Collection (Houston, Texas)

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia (Madrid)

- Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

- Museum of Modern Art (New York City)

- Nasher Sculpture Center (Dallas, Texas)

- Nassau County Museum of Art (Roslyn Harbor, New York)

- National Gallery of Art (Washington D.C.)

- National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa)

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

- Sheldon Museum of Art (Lincoln, Nebraska)

- Smithsonian American Art Museum (Washington D.C.)

- Stedelijk Museum (Amsterdam)

- Tate Gallery (London)

- Wadsworth Atheneum (Hartford, Connecticut)

- Walker Art Center (Minneapolis, Minnesota)

- Wallraf-Richartz-Museum (Cologne, Germany)

- Whitney Museum of American Art (New York City)

Art market

[edit]After Newman had an artistic breakthrough in 1948, he and his wife decided that he should devote all his energy to his art. They lived almost entirely off Annalee Newman's teaching salary until the late 1950s, when Newman's paintings began to sell consistently.[3] Ulysses (1952), a blue-and-black striped painting, sold in 1985 for $1,595,000 at Sotheby's to an American collector who was not identified.[19] Consigned by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen and previously part of Frederick R. Weisman's collection, Newman's 8.5-by-10-foot Onement VI (1953) was sold for a record $43.8 million at Sotheby's New York in 2013; its sale was ensured by an undisclosed third-party guarantee.[20] This was eclipsed on May 13, 2014, when Black Fire 1 sold for $84.2 million.[21]

See also

[edit]- Black Fire I painted by Newman in 1961

- Voice of Fire painted by Newman in 1967

- Broken Obelisk

- Vir Heroicus Sublimis

References

[edit]- ^ Sylvester, David (1998). The Grove Book of Art Writing. New York, NY: Grove Press. p. 537. ISBN 0802137202. Barnet Newman:"The painting should give man a sense of place: that he knows he's there, so he's aware of himself. In that sense he relates to me when I made the painting because in that sense I was there...[Hopefully] you [have] a sense of your own scale [standing in front of the painting]...To me that sense of place has not only a sense of mystery but also has a sense of metaphysical fact. I have come to distrust the episodic, and I hope that my painting has the impact of giving someone, as it did me, the feeling of his own totality, of his own separateness, of his own individuality and the same time of his connection to others, who are also separate."

- ^ a b The Barnett Newman Foundation website: Chronology of the Artist's Life page

- ^ a b Roberta Smith (May 13, 2000), Annalee Newman, 91, Muse And Support for the Artist The New York Times.

- ^ Barbara Hess (2005). Abstract Expressionism. Taschen. p. 40. ISBN 978-382282970-7

- ^ John P. O'Neill, ed. (1990). Barnett Newman Selected Writings and Interviews. University of California Press. pp. 240–241. ISBN 9780520078178.

- ^ John P. O'Neill, ed. (1990). Barnett Newman Selected Writings and Interviews. University of California Press. p. 201. ISBN 9780520078178.

- ^ "Barnett Newman | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2022-01-28.

- ^ Cotkin, G. (2005). Existential America. United Kingdom: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 83. ISBN 9780801882005.

- ^ Barnett Newman Foundation, archive 18/103

- ^ a b Chilvers, Ian and Glaves-Smith, John, A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art, second edition (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), ISBN 0199239665.

- ^ Menachem Wecker (August 1, 2012). "His Cross To Bear. Barnett Newman Dealt With Suffering in 'Zips'". The Jewish Daily Forward. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- ^ "Subject of the Artist | art school". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Chilvers, Ian; Glaves-Smith, John (2009). "Subjects of the Artist School". A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923966-5. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Breslin, p. 223.

- ^ The Barnett Newman Foundation website: About the Foundation page

- ^ "The Barnett Newman Foundation website: Catalogue Raisonne page". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ^ Most frequently requested artists list of the Artists Rights Society Archived February 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Acquisitions of the month: August-September 2018". Apollo Magazine. 3 October 2018.

- ^ Rita Reif (May 3, 1985), Barnett Newman's 'Ulysses' Sold At Sotheby's Auction The New York Times.

- ^ Katya Kazakina and Philip Boroff (May 15, 2013), Barnett Newman Leads Sotheby’s NYC $294 Million Auction Bloomberg

- ^ Kathryn Tully (2014-05-14). "New Artists Set Auction Records At Christie's Biggest Ever Sale". Forbes.

Further reading

[edit]- Ellyn Childs Allison, ed., Barnett Newman: A Catalogue Raisonné (Yale University Press, 2004.) ISBN 0-300-10167-8

- Bruno Eble (2011). Barnett Newman et l'art roman (in French). Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-296-55188-6.

- Yve-Alain Bois. "Perceiving Newman," in Painting as Model (Cambridge, MA/London: MIT Press, 1995).

- Mark Godfrey (2007). Abstraction and the Holocaust. Yale University Press. pp. 51–78. ISBN 978-0-300-12676-1.

- Marika Herskovic, American Abstract Expressionism of the 1950s An Illustrated Survey Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine (New York School Press, 2003.) ISBN 0-9677994-1-4

- Ann Temkin, Barnett Newman (Yale University Press, 2002.) [Catalogue for the Exhibition "Barnett Newman," Philadelphia Museum of Art, March 24 to July 7, 2002; Tate Modern London, September 19, 2002, to January 5, 2003] ISBN 0-87633-156-8

- Jean-Francois Lyotard, "Newmann: The Instant", in: Jean-Francois Lyotard, Miscellaneous Texts II: Contemporary Artists (Leuven University Press, 2012.) ISBN 978-90-586-7886-7

External links

[edit]- Barnett Newman at the National Gallery of Art

- The Barnett Newman Foundation

- Barnett Newman at the Museum of Modern Art

- Barnett Newman at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Newman's page at the Tate Gallery (includes images of the 18 Cantos and other works)

- American Museum of Natural History, Dept. of Anthropology correspondence with Barnett Newman and Betty Parsons, 1944-1946 in the collection of the Smithsonian Archives of American Art

- 20th-century American painters

- American male painters

- Abstract expressionist artists

- American abstract painters

- 1905 births

- 1970 deaths

- Painters from New York City

- Jewish sculptors

- Jewish American painters

- Art Students League of New York alumni

- American people of Polish-Jewish descent

- City College of New York alumni

- 20th-century American Jews

- 20th-century American male artists

- Burials at Montefiore Cemetery