Anglican doctrine

| Part of a series on |

| Anglicanism |

|---|

|

|

|

Anglican doctrine (also called Episcopal doctrine in some countries) is the body of Christian teachings used to guide the religious and moral practices of Anglicanism.[1]

Thomas Cranmer, the guiding Reformer that led to the development of Anglicanism as a distinct tradition under the English Reformation, compiled the original Book of Common Prayer, which forms the basis of Anglican worship and practice.[2][1] By 1571 it included the Thirty-nine Articles, the historic doctrinal statement of the Church of England.[1] The Books of Homilies explicates the foundational teachings of Anglican Christianity, also compiled under the auspices of Archbishop Cranmer.[1] Richard Hooker and the Caroline divines later developed Anglican doctrine of religious authority as being derived from scripture, tradition, and "redeemed" reason; Anglicans affirmed the primacy of scriptural revelation (prima scriptura), informed by the Church fathers, the historic Nicene, Apostles and Athanasian creeds, and a latitudinarian interpretation of scholasticism. Charles Simeon espoused and popularised evangelical Reformed positions in the 18th and 19th centuries, while the Oxford Movement re-introduced monasticism, religious orders and various other pre-Reformation practices and beliefs in the 19th century.

Anglicanism historically developed as via media between two branches of Protestantism—Lutheranism and Calvinism—though closer to the latter than the former.[3][4] Its identity has affirmed to be Reformed and Catholic.[3]

Over time, the tension between catholicity and Puritanism resulted in a latitudinarian or "broad church" mainstream, within a low church to high church spectrum of sanctioned approaches to ritual and tolerance of the associated beliefs. Evangelicals (low church) and Anglo Catholics (high church) represent the far ends of this spectrum, with most Anglicans falling somewhere in between. Theologically, the Anglican Communion includes Reformed Anglicanism, with a smaller number of Arminian Anglicans.[5]

Approach to doctrine

[edit]There are two streams informing doctrinal development and understanding in Anglicanism. The first of these includes the historic formularies of Anglicanism.[4] Historical formularies of Anglicanism include Books of Common Prayer, ordinals and the "standard divines". Most prominent of the historical formularies are the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion, principally authored by Thomas Cranmer.[1] These are divided into four sections, moving from the general (the fundamentals of the faith) to the particular (the interpretation of scripture, the structure and authority of the church, and the relationship between church and society). Other significant formularies include The Books of Homilies, listed in Article XXXV in the Articles of Religion; this explicates the theology of historic Anglicanism.[1]

Some Anglicans also take the principle of lex orandi, lex credendi seriously, regarding the content, form and rubrics of liturgy as an important element of doctrinal understanding, development and interpretation. Secondly, Anglicans cite the work of the standard divines, or foundational theologians, of Anglicanism as instructive. Such divines include Cranmer, Richard Hooker, Matthew Parker, John Ponet, Lancelot Andrewes and John Jewel.

Anglican doctrine affirms the three major creeds of the early ecumenical councils (the Apostles', Nicene and Athanasian creeds), the principles enshrined in the "Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral" and the dispersed authority of the four instruments of Communion of the Anglican Communion.

The second stream of doctrine is contained in the formally adopted doctrinal positions of the constitutions and canon law of various national churches and provinces of the Anglican Communion. These are usually formulated by general synods of national or regional churches and interpreted and enforced by a bishop-in-council structure, involving consultation between the bishops and delegated lay and clerical leadership, although the extent of the devolution of authority from the bishops varies from place to place. This stream is the only binding and enforceable expression of doctrine in Anglicanism, which can sometimes result in conflicting doctrinal understandings between and within national churches and provinces.

Interpretation of doctrine

[edit]The foundations and streams of doctrine are interpreted through the lenses of various Christian movements which have gained wide acceptance among clergy and laity. Prominent among those in the latter part of the 20th century and the early 21st century are Liberal Christianity, Anglo-Catholicism and Evangelicalism, which includes Reformed Anglicanism, along with a smaller number of Arminian Anglicans (though a number of them became a part Methodism).[5] These perspectives emphasise or supplement particular aspects of historical theological writings, canon law, formularies and prayer books. Because of this, these perspectives often conflict with each other and can conflict with the formal doctrines. Some of these differences help to define "parties" or "factions" within Anglicanism. However, with certain notable exceptions that led to schisms, Anglicans have grown a tradition of tolerating internal differences. This tradition of tolerance is sometimes known as "comprehensiveness".

Origins

[edit]Anglican doctrine emerged from the interweaving of two main strands of Christian doctrine during the English Reformation in the 16th and 17th centuries. The first strand comes from the Catholic doctrine taught by the established church in England in the early 16th century. The second strand represents a range of Reformed Protestant teachings brought to England from neighbouring countries in the same period, notably Calvinism[Note 1] and Lutheranism.[3]

Anglican doctrine is often said to be both Reformed and Catholic.[3] At the time of the English Reformation, the Church of England formed the local expression of the institutional Roman Catholic Church in England. Canon law had documented the formal doctrines over the centuries and the Church of England still follows an unbroken tradition of canon law today[update]. The English Reformation did not dispense with all previous doctrines. The church not only retained the core Catholic beliefs common to Reformed doctrine in general, such as the Trinity, the virginal conception of Mary, the nature of Jesus as fully human and divine, the resurrection of Jesus, original sin and excommunication (as affirmed by the Thirty-Nine Articles), but also retained some historic Catholic teachings which were not practiced by the Continental Reformed churches, such as the three orders of ministry and the apostolic succession of bishops, though these were retained by the Scandinavian Lutheran Churches (such as the Church of Sweden). Peter Robinson, presiding bishop of the United Episcopal Church of North America, writes:[7]

Cranmer's personal journey of faith left its mark on the Church of England in the form of a Liturgy that remains to this day more closely allied to Lutheran practice, but that liturgy is couple to a doctrinal stance that is broadly, but decidedly Reformed. ... The 42 Articles of 1552 and the 39 Articles of 1563, both commit the Church of England to the fundamentals of the Reformed Faith. Both sets of Articles affirm the centrality of Scripture, and take a monergist position on Justification. Both sets of Articles affirm that the Church of England accepts the doctrine of predestination and election as a 'comfort to the faithful' but warn against over much speculation concerning that doctrine. Indeed a casual reading of the Wurttemburg Confession of 1551, the Second Helvetic Confession, the Scots Confession of 1560, and the XXXIX Articles of Religion reveal them to be cut from the same bolt of cloth.[7]

Foundational elements

[edit]Scripture, creeds and ecumenical councils

[edit]Central to Anglican doctrine are the foundational documents of Christianity – all the books of the Old and New Testaments are accepted, but the books of the Apocrypha, while recommended as instructive by Article VI of the Thirty-Nine Articles, are declared not "to establish any doctrine".

Article VIII of the Thirty-Nine Articles declared the three Catholic creeds – the Apostles', the Nicene and the Athanasian – to "be proved by most certain warrants of holy Scripture" and were included in the first and subsequent editions of The Book of Common Prayer. All Anglican prayer books continue to include the Apostles' and Nicene Creed. Some — such as the Church of England's Common Worship or A New Zealand Prayer Book — omit the Athanasian Creed, but include alternative "affirmations". This liturgical diversity suggests that the principles enunciated by the Apostles' and Nicene creeds remain doctrinally unimpeachable. Nonetheless, metaphorical or spiritualised interpretations of some of the creedal declarations – for instance, the virgin birth of Jesus and his resurrection – have been commonplace in Anglicanism since the integration of biblical critical theory into theological discourse in the 19th century.[citation needed]

The first four ecumenical councils of Nicea, Constantinople, Ephesus, and Chalcedon "have a special place in Anglican theology, secondary to the Scriptures themselves." [8] This authority is usually considered to pertain to questions of the nature of Christ (the hypostasis of divine and human) and the relationships between the Persons of the Holy Trinity, summarised chiefly in the creeds which emerged from those councils. Nonetheless, Article XXI of The Thirty-Nine Articles limit the authority of these and other ecumenical councils, noting that "they may err, and sometimes have erred." In other words, their authority being strictly derivative from and accountable to scripture.

Thirty-Nine Articles

[edit] Works related to Thirty-Nine Articles at Wikisource

Works related to Thirty-Nine Articles at Wikisource

Reformed doctrine and theology were developed into a distinctive English form by bishops and theologians led by Thomas Cranmer and Matthew Parker. Their doctrine was summarised in the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion which were adopted by the Parliament of England and the Church of England in 1571.

The early English Reformers, like contemporaries on the European continent such as John Calvin, John Knox and Martin Luther, rejected many Roman Catholic teachings. The Thirty-Nine Articles list core Reformed doctrines such as the sufficiency of the Holy Scriptures for salvation, the execution of Jesus as "the perfect redemption, propitiation, and satisfaction for all the sins of the whole world", Predestination and Election. Some of the articles are simple statements of opposition to Roman Catholic doctrine, such as Article XIV which denies "Works of Supererogation", Article XV which implicitly excludes the Immaculate Conception, and XXII which explicitly rejects the concept of Purgatory. Catholic worship and teaching was at the time conducted in Latin, while the Articles required church services to use the vernacular. The Articles reveal Calvinist influence, but moderately (double predestination is rejected; God has willed some to redemption because of foresight, but does not will any to perdition), and reject other strands of Protestant teachings such as the corporeal Real Presence of Lutheranism (but agree on Justification by Faith alone), Zwinglianism, such as those of the doctrine of common property of "certain Anabaptists". Transubstantiation is rejected: i.e. the bread and wine remain in their natural properties. However, the real and essential presence of Christ in the eucharist is affirmed but "only after an heavenly and spiritual manner", consistent with a Reformed view of the Lord's Supper (cf. Lord's Supper in Reformed theology).[9]

In contrast to Calvin, the Articles did not explicitly reject the Lutheran doctrine of Sacramental Union, a doctrine which is often confused with the medieval Lollard doctrine of Consubstantiation. The Articles also endorse an Episcopal polity, and the English monarch as Supreme Governor of the Church of England to replace the Bishop of Rome. The Articles can also be read as permitting the acceptance of the five so-called "non-dominical" sacraments of private confession, marriage, ordination, anointing of the sick, and confirmation as legitimately sacramental, in addition to Baptism and the Eucharist. The Sacrifice of Masses is rejected. The doctrine of the eucharistic as the Church's sacrifice or oblation to God, dating from the second century A.D., is rejected but the Holy Communion is referred to as the Sacrifice of Praise and Thanksgiving in an optional Prayer of Oblation after the reception of Communion.

The Church of England has not amended the Thirty-Nine Articles. However, synodical legislators made changes to canon law to accommodate those who feel unable to adhere strictly to the Thirty-Nine Articles. The legal form of the declaration of assent required of clergy on their appointment, which was at its most rigid in 1689, was amended in 1865 and again in 1975 to allow more latitude. Outside of the Church of England, the Articles have an even less secure status and are generally treated as an edifying historical document not binding on doctrine or practice.

Homilies

[edit]

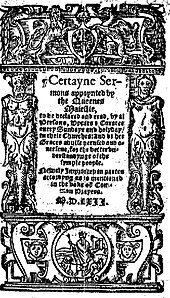

The Homilies are two books of thirty-three sermons developing Reformed doctrines in greater depth and detail than in the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion. During the reigns of Edward VI and Elizabeth I, Thomas Cranmer and other English Reformers saw the need for local congregations to be taught Christian theology and practice. Sermons were appointed and required to be read each Sunday and holy day in English. Some are straightforward exhortations to read scripture daily and lead a life of faith; others are rather lengthy scholarly treatises directed at academic audiences on theology, church history, the fall of the Christian Empire and the heresies of Rome.

The Homilies are noteworthy for their beautiful and magisterial phrasing and the instances of historical terms. Each homily is heavily annotated with references to scripture, the church fathers, and other primary sources. The reading of the Homilies in church is still directed under Article XXXV of the Thirty-Nine Articles.

Prayer books

[edit]The original Book of Common Prayer of the Church of England was published in 1549, and its most recently approved successor was issued in 1662. It is this edition that national prayer-books (with the exception of Scotland's) used as a template as the Anglican Communion spread outside England. The foundational status of the 1662 edition has led to its being cited as an authority on doctrine. This status reflects a more pervasive element of Anglican doctrinal development, namely that of lex orandi, lex credendi, or "the law of prayer is the law of belief".[Note 2]

Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral

[edit]The Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral is a summation of the Anglican approach to theology, worship and church structure and is often cited as a basic summary of the essentials of Anglican identity. The four points are:

- The Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments, as "containing all things necessary to salvation," and as being the rule and ultimate standard of faith.

- The Creeds (specifically, the Apostles' and Nicene) as the sufficient statement of Christian faith;

- The dominical sacraments of Baptism and Holy Communion;

- The historic episcopate locally adapted.

The four points originated in resolutions of the Episcopal Church in the United States of 1886 and were (more significantly) modified and finalised in the 1888 Lambeth Conference of bishops of the Anglican Communion. Primarily intended as a means of pursuing ecumenical dialogue with the Roman Catholic Church, the Quadrilateral soon became a "sine qua non" for essential Anglican identity.

Standard divines

[edit]Anglicanism has writers whose works are regarded as standards for faith and doctrine. While there is no definitive list, such individuals are implicitly recognised as authoritative by their inclusion in Anglican liturgical calendars or in anthologies of works on Anglican theology. These include such early figures as Thomas Cranmer, Lancelot Andrewes, John Cosin, Richard Hooker, John Jewel, Matthew Parker, and Jeremy Taylor; and later figures such as Joseph Butler, William Law, John Wesley, and George Whitefield. The 19th century produced several prominent Anglican thinkers, notably John Keble, Frederick Denison Maurice, John Henry Newman, Edward Pusey, and John Charles Ryle. More recently, Charles Gore, Michael Ramsey, and William Temple have been included among the pantheon. While this list gives a snapshot, it is not exhaustive.

Doctrinal development

[edit]Given that the foundational elements of Anglican doctrine are either not binding or are subject to local interpretation, methodology has tended to assume a place of key importance. Hence, it is not so much a body of doctrinal statements so much as the process of doctrinal development that is important in Anglican theological identity.[citation needed]

Lex orandi, lex credendi

[edit]Anglicanism has traditionally expressed its doctrinal convictions based on the prayer texts and liturgy of the church. In other words, appeal has typically been made to what Anglicans do and prescribe in common worship, enunciated in the texts of the Book of Common Prayer and other national prayer books, to guide theology and practice. Applying this axiom to doctrine, there are three venues for its expression in the worship of the Church:

- The selection, arrangement, and composition of prayers and exhortations;

- The selection and arrangement of the lectionary; and

- The rubrics (regulations) for liturgical action and variations in the prayers and exhortations.[10]

The principle of lex orandi, lex credendi functions according to the so-called "three-legged stool" of scripture, tradition, and reason attributed to Richard Hooker.[11] This doctrinal stance is intended to enable Anglicanism to construct a theology that is pragmatic, focused on the institution of the church, yet engaged with the world. It is, in short, a theology that places a high value on the traditions of the faith and the intellect of the faithful, acknowledging the primacy of the worshipping community in articulating, amending, and passing down the church's beliefs. In doing so, Anglican theology is inclined towards a comprehensive consensus concerning the principles of the tradition and the relationship between the church and society. In this sense, Anglicans have viewed their theology as strongly incarnational – expressing the conviction that God is revealed in the physical and temporal things of everyday life and the attributes of specific times and places.

This approach has its hazards, however. For instance, there is a countervailing tendency to be "text-centric", that is, to focus on the technical, historical, and interpretative aspects of prayer books and their relationship to the institution of the church, rather than on the relationship between faith and life. Second, the emphasis on comprehensiveness often instead results in compromise or tolerance of every viewpoint. The effect that is created is that Anglicanism may appear to stand for nothing or for everything, and that an unstable and unsatisfactory middle-ground is staked while theological disputes wage interminably. Finally, while lex orandi, lex credendi helped solidify a uniform Anglican perspective when the 1662 Prayer Book and its successors predominated, and while expatriate bishops of the United Kingdom enforced its conformity in territories of the British Empire, this has long since ceased to be true. Liturgical reform and the post-colonial reorganisation of national churches has led to a growing diversity in common worship since the middle of the 20th century.

Process of doctrinal development

[edit]

The principle of lex orandi, lex credendi discloses a larger theme in the approach of Anglicanism to doctrine, namely, that doctrine is considered a lived experience; since in living it, the community comes to understand its character. In this sense, doctrine is considered to be a dynamic, participatory enterprise rather than a static one.

This inherent sense of dynamism was articulated by John Henry Newman a century and a half ago, when he asked how, given the passage of time, we can be sure that the Christianity of today is the same religion as that envisioned and developed by Jesus Christ and the apostles.[Note 3] As indicated above, Anglicans look to the teaching of the Bible and of the undivided Church of the first five centuries as the sufficient criterion for an understanding of doctrine, as expressed in the creeds. Yet they are only a criterion: interpretation, and thus doctrinal development, is thoroughly contextual. The reason this is the case is chiefly due to three factors:

- Differing theories of interpretation of scripture, developed as a result of the symbolic nature of language, the difficulty of translating its cultural and temporal aspects, and the particular perceptual lenses worn by authors;

- The accumulation of knowledge through science and philosophy; and

- The emerging necessity of giving some account of the relationship of Christ to distinct and evolving cultural realities throughout the world, as Christianity has spread to different places.

Newman's suggestion of two criteria for the sound development of doctrine has permeated Anglican thinking. These are, first, that development must be open and accessible to the faithful at every stage; and second, that it must be subject to appeal to scripture and the precedents of antiquity through the process of sound scholarship. The method by which this is accomplished is by the distillation of doctrine through, and its subordination to a dominant Anglican ethos consisting of the maintenance of order through consensus, comprehensiveness, and contract; and a preference for pragmatism over speculation.[12] In other words, the former — experience — flows from the latter — method. Anglican doctrinal methodology means concurrence with a base structure of shared identity: An agreement on the fundamentals of the faith articulated in the creeds; the existence of Protestant and catholic elements creating both a via media as well as a "union of opposites";[Note 4] and the conviction that there is development in understanding the truth, expressed more in practical terms rather than theoretical ones.[13] In short, the character of Anglicanism is that the church "contains in itself many elements regarded as mutually exclusive in other communions."[14]

Formal doctrine

[edit]Anglican churches in other countries generally inherited the doctrinal apparatus of the Church of England, consisting most commonly an adaptation of the Thirty-Nine Articles and the Quadrilateral into general principles. From the earliest times, they have adapted them to suit their local needs.

Constitutions and canon law

[edit]Canon law in the churches of the Anglican Communion stem from the law of the patristic and Medieval Western church which was received, along with the limiting conditions of the English Reformation. Canon law touches on several areas of church life: ecclesiology, that is, the governance and structure of the church as an institution; liturgy; relationships with secular institutions; and the doctrines which implicitly or explicitly touch on these matters. Such laws have varying degrees and means of enforcement, variability, and jurisdiction.

The nature of canon law is complicated by the status of the Church of England as subordinate to the crown; a status which does not affect jurisdictions outside England, including those of the Scottish Episcopal Church, the Church of Ireland, and the Church in Wales. It is further complicated by the relationship between the autonomous churches of the Communion itself; since the canon law of one jurisdiction has no status in that of another. Moreover, there is — as mentioned above — no international juridical system which can formulate or enforce uniformity in any matter. This has led to conflict regarding certain issues (see below), leading to calls for a "covenant" specifying the parameters of Anglican doctrinal development (see Anglican realignment for discussion).

Instruments of unity

[edit]As mentioned above, the Anglican Communion has no international juridical organisation. The Archbishop of Canterbury's role is strictly symbolic and unifying, and the Communion's three international bodies are consultative and collaborative, their resolutions having no legal effect on the independent provinces of the Communion. Taken together, however, the four do function as "instruments of unity", since all churches of the Communion participate in them. In order of antiquity, they are:

- The Archbishop of Canterbury, as the spiritual head of the Communion, is the focus of unity, since no church claims membership in the Communion without being in communion with him.

- The Lambeth Conference is a consultation of the bishops of the Communion, intended to reinforce unity and collegiality through manifesting the episcopate, to discuss matters of mutual concern, and to pass resolutions intended to act as guideposts. It is held roughly every ten years and invitation is by the Archbishop of Canterbury.

- The Anglican Consultative Council meets usually at three year intervals. Consisting of representative bishops, clergy, and laity chosen by the thirty-eight provinces, the body has a permanent secretariat, the Anglican Communion Office, of which the Archbishop of Canterbury is president.

- The Primates' Meeting is the most recent manifestation of international consultation and deliberation, having been first convened by Archbishop of Canterbury Donald Coggan as a forum for "leisurely thought, prayer and deep consultation."[15]

Since there is no binding authority in the Communion, these international bodies are a vehicle for consultation and persuasion. In recent years, persuasion has tipped over into debates over conformity in certain areas of doctrine, discipline, worship, and ethics.

Controversies

[edit]Historical background

[edit]The effect of nationalising the Catholic faith in England inevitably led to conflict between factions wishing to remain obedient to the Pope, those wishing more radical reform, and those holding a middle ground. A range of Presbyterian, Congregational, Baptist and other Puritan views gained currency in the Church in England, Ireland, and Wales through the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Although the Pilgrim Fathers felt compelled to leave for New England, other Puritans gained increasing ecclesiastical and political authority, while Royalists advocated Arminianism and the Divine Right of Kings. This conflict was one of the ultimate causes of the English Civil War. The Church of England, with the assistance of Presbyterian Church of Scotland theologians and clergy, set down their newly developed Calvinist doctrines in the Westminster Confession of 1648, which was never formally adopted into church law. After the Restoration of 1660 and the 1662 Act of Uniformity reinforced Cranmer's Anglicanism, those wishing to hold to the stricter views set out at Westminster either emigrated or covertly founded non-conformist Presbyterian, Congregational, or Baptist churches at home.

The 18th century saw the Great Awakening, the Methodist schism, and the identification of the Evangelical party among the many conservatives who remained in the Anglican churches. The schism with the Methodists in the 18th century had a theological aspect (with Methodism being Arminian), particularly concerning the Wesleyan emphasis on personal salvation by faith alone, although John Wesley continued to regard himself as a member of the Church of England. The same period also saw the emergence of the High Church movement, which began to identify with the Catholic heritage of Anglicanism, and to emphasise the importance of the Eucharist and church tradition, while mostly rejecting the legitimacy of papal authority in England. The High Churchmen gave birth to the Oxford Movement and the resulting Anglo-Catholic party of Anglicanism in the 19th century, which also saw the emergence of Liberal Christianity across the Protestant world.

The mid-19th century saw doctrinal debate between adherents of the Oxford Movement and their Low Church or Evangelical opponents, though the most public conflict tended to involve more superficial matters such as the use of church ornaments, vestments, candles, and ceremonial (which were taken to indicate a sympathy with Roman Catholic doctrine), and the extent to which such matters ought to be restricted by the church authorities. These conflicts led to further schism, for example in the creation of the Reformed Episcopal Church in North America.

Doctrinal controversies in the 20th century

[edit]

Beginning in the 17th century, Anglicanism came under the influence of latitudinarianism, chiefly represented by the Cambridge Platonists, who held that doctrinal orthodoxy was less important than applying rational rigour to the examination of theological propositions. The increasing influence of German higher criticism of the Bible throughout the 19th century, however, resulted in growing doctrinal disagreement over the interpretation and application of scripture. This debate was intensified with the accumulation of insights derived from the natural and social sciences which tended to challenge literally read biblical accounts. Figures such as Joseph Lightfoot and Brooke Foss Westcott helped mediate the transition from the theology of Hooker, Andrewes, and Taylor to accommodate these developments. In the early 20th century, the liberal Catholicism of Charles Gore and William Temple attempted to fuse the insights of modern biblical criticism with the theology expressed in the creeds and by the Apostolic Fathers, but the following generations of scholars, such as Gordon Selwyn and John Robinson questioned what had hitherto been the sacrosanct status of these verities. As the century progressed, the conflict sharpened, chiefly finding its expression in the application of biblically derived doctrine to social issues.

Anglicans have debated the relationship between doctrine and social issues since its origins, when the focus was chiefly on the church's proper relationship to the state. Later, in the 18th and early 19th centuries, the focus shifted to slavery. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Anglicans fiercely debated the use of artificial contraception by Christian couples, which was prohibited by church teaching. In 1930 the Lambeth Conference took a lone stand among major Christian denominations at the time and permitted its use in some circumstances[16] (see also Christian views on contraception).

The 20th century also saw an intense doctrinal debate among Anglicans over the ordination of women, which led to schism, as well as to the conversion of some Anglican clergy to Roman Catholicism. Even today, there is no unanimity of doctrine or practice in the Anglican Communion as it relates to women's ordination. Finally, in the 1950s, '60s, and '70s Anglican churches wrestled with the issue of the remarriage of divorced persons, which was prohibited by dominical commandment. Once again, there is presently no unanimity of doctrine or practice.

Current controversies

[edit]

The focus of doctrinal debate on issues of social theology has continued into the 21st century. Indeed, the eclipse of issues of classical doctrine, such as confessions of faith, has been exemplified by the relatively non-controversial decisions by some Communion provinces to amend the Nicene Creed by dropping the filioque clause, or supplementing the historic creeds with other affirmations of faith.[Note 5] As of 2016, the prominent doctrinal issue being actively debated in Anglican synods and convocations across the world is the place of gay and lesbian people in the life of the church — specifically with respect to same-sex unions and ordination (see Homosexuality and the Anglican Communion).

The consecration of bishops and the extension of sacraments to individuals based on gender or sexual orientation would ordinarily be matters of concern to the synods of the autonomous provinces of the Communion. Insofar as they affect other provinces, it is by association — either the physical association between the individuals to whom the sacraments have been extended and those who oppose such extension; or the perceptual association of Anglicanism generally with such practices. Regardless, these issues have incited debate over the parameters of domestic autonomy in doctrinal matters in the absence of international consensus. Some dioceses and provinces have moved further than others can easily accept, and some conservative parishes within them have sought pastoral oversight from bishops of other dioceses or provinces, in contravention of traditional Anglican polity (see Anglican realignment). These developments have led some to call for a covenant to delimit the power of provinces to act on controversial issues independently, while others have called for a renewed commitment to comprehensiveness and tolerance of diverse practice.

See also

[edit]- Anglican Eucharistic theology

- History of Calvinist–Arminian debate

- Anglican Marian theology

- Anglican sacraments

- Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral

- Ritualist movement

- Bangorian Controversy

- Nonjuring schism

- Christian theological controversy

Some contemporary Anglican theologians

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Although Calvinism by the end of the 16th century was the ruling theology in England among conformists and nonconformists alike, the Episcopalian Anglicans would only accept Calvinistic doctrines of predestination, justification, sanctification, etc. They did not follow Calvin in his ecclesiology, certainly not in his conception of church-government.[6]

- ^ For a short article on this concept, from which much of the content of this section is derived, see Stevenson (1998), pp. 174–188.

- ^ For Newman's discussion of doctrinal development, see Newman (1909).

- ^ A phrase used by Frederick Denison Maurice in Maurice (1958), p. 311.

- ^ See for example the Church of England's Common Worship texts, which include several forms of affirmation alongside the traditional creeds.[17]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Samuel, Chimela Meehoma (28 April 2020). Treasures of the Anglican Witness: A Collection of Essays. Partridge Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5437-5784-2.

In addition to his emphasis on Bible reading and the introduction to the Book of Common Prayer, other media through which Cranmer sought to catechize the English people were the introduction of the First Book of Homilies and the 39 Articles of Religion. Together with the Book of Common Prayer and the Forty-Two Articles (which were later reduced to thirty-nine), the Book of Homilies stands as one of the essential texts of the Edwardian Reformation, and they all helped to define the shape of Anglicanism then, and in the subsequent centuries. More so, the Articles of Religion, whose primary shape and content were given by Archbishop Cranmer and Bishop Ridley in 1553 (and whose final official form was ratified by Convocation, the Queen, and Parliament in 1571), provided a more precise interpretation of Christian doctrine to the English people. According to John H. Rodgers, they "constitute the formal statements of the accepted, common teaching put forth by the Church of England as a result of the Reformation."

- ^ Goggin, Jamin; Strobel, Kyle (5 June 2013). Reading the Christian Spiritual Classics: A Guide for Evangelicals. InterVarsity Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-8308-3997-1.

Thomas Cranmer shaped the piety and theology of the reformed Church of England through his Book of Common Prayer.

- ^ a b c d Anglican and Episcopal History. Historical Society of the Episcopal Church. 2003. p. 15.

Others had made similar observations, Patrick McGrath commenting that the Church of England was not a middle way between Roman Catholic and Protestant, but "between different forms of Protestantism", and William Monter describing the Church of England as "a unique style of Protestantism, a via media between the Reformed and Lutheran traditions". MacCulloch has described Cranmer as seeking a middle way between Zurich and Wittenberg but elsewhere remarks that the Church of England was "nearer Zurich and Geneva than Wittenberg.

- ^ a b Jensen, Michael P. (7 January 2015). "9 Things You Should Really Know About Anglicanism". The Gospel Coalition. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

The theology of the founding documents of the Anglican church—the Book of Homilies, the Book of Common Prayer, and the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion—expresses a theology in keeping with the Reformed theology of the Swiss and South German Reformation. It is neither Lutheran, nor simply Calvinist, though it resonates with many of Calvin's thoughts.

- ^ a b Hampton, Stephen. "Anti-Arminians: The Anglican Reformed Tradition from Charles II to George I". The Gospel Coalition. Retrieved 27 November 2024.

- ^ Paas (2007), p. 70

- ^ a b Robinson, Peter (2 August 2012). "The Reformed Face of Anglicanism". The Old High Churchman. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ Shriver (1988), p. 189

- ^ Strout, Shawn O. (29 February 2024). Of Thine Own Have We Given Thee: A Liturgical Theology of the Offertory in Anglicanism. James Clarke & Company. p. 35-36. ISBN 978-0-227-17995-6.

- ^ Stevenson (1998), p. 175

- ^ Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, III.8.13-15; and V.8.2. Hooker himself, however, never used the "stool" analogy.

- ^ Stevenson (1998), pp. 177–179

- ^ Sykes (1978), p. 10ff

- ^ Sykes (1978), p. 8

- ^ Quoted, for example, by the 2004 Windsor report (accessed 2007-07-17), where it is sourced to the Lambeth Conference 1978, Report, p. 123.

- ^ Kathleen O'Grady, 1999 "Contraception and religion, A short history" from The Encyclopedia of Women and World Religion (Serinity Young et al. eds). Macmillan, 1999, reprinted on http://www.mum.org/contrace.htm, retrieved August 15, 2006

- ^ Creeds and Authorized Affirmations of Faith Archived 2010-05-26 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2008-04-21

Bibliography

[edit]- Maurice, Frederick Denison (1958) [1842]. The Kingdom of Christ. Vol. II. London: SCM.

- Newman, John Henry (1909) [1845]. Essays on the Development of Doctrine. London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Paas, Stephen (2007). Ministers and Elders: The Birth of Presbyterianism. Kachere theses. African Books Collective. p. 70. ISBN 9789990887020.

- Shriver, Frederick P. (1988). "Councils, Conferences, and Synods". In Booty, John E.; Sykes, Stephen; Knight, Jonathan (eds.). The Study of Anglicanism. S.P.C.K. ISBN 978-1-4514-1118-8.

- Stevenson, W. Taylor (1998). "Lex Orandi—Lex Credendi". In Booty, John E.; Sykes, Stephen; Knight, Jonathan (eds.). The Study of Anglicanism. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-1118-8.

- Sykes, Stephen (1978). The Integrity of Anglicanism. London and Oxford: Mowbray & Co.

Further reading

[edit]- Buchanan, Colin (2015). Historical Dictionary of Anglicanism. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-5016-1.

- Chapman, Mark (2013). Anglican Theology. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0567008022.

- Gore, Charles (1951). The Reconstruction of Belief: Belief in God. Belief in Christ. The Holy Spirit and the Church. J. Murray. Originally published 1921–1924 in three separate volumes, published in 1926 in one volume.

- Hughes, Phillip Edgecumbe (1982). Owen C. Thomas (ed.). Introduction to Theology. Morehouse-Barlow. ISBN 978-0-8192-1315-0.

- MacDougall, Scott (2022). The Shape of Anglican Theology: Faith Seeking Wisdom. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-51785-1.