Andrew Vachss

Andrew Vachss | |

|---|---|

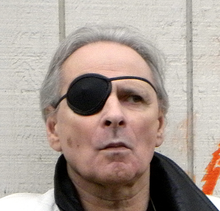

Vachss in 2011 | |

| Born | October 19, 1942 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | November 23, 2021 (aged 79) Pacific Northwest, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Crime novel |

| Notable works | |

| Signature | |

| |

| Website | |

| vachss | |

Andrew Henry Vachss (/væks/ VAX;[1] October 19, 1942 – November 23, 2021) was an American crime fiction author, child protection consultant, and attorney exclusively representing children and youths.[2]

Early life and career

[edit]Vachss grew up in Manhattan on the Lower West Side.[3] Before becoming a lawyer, Vachss held many front-line positions in child protection.[4] He was a federal investigator in sexually transmitted diseases, and a New York City social-services caseworker. He worked in Biafra,[5] entering the war zone just before the fall of the country.[6] There he worked to find a land route to bring donated food and medical supplies across the border[7] after the seaports were blocked and Red Cross airlifts banned by the Nigerian government;[8] however, all attempts ultimately failed, resulting in rampant starvation.[9]

After he returned and recovered from his injuries, including malaria and malnutrition,[10] Vachss studied community organizing in 1970 under Saul Alinsky.[6] He worked as a labor organizer and ran a self-help center for urban migrants in Chicago.[11] He then managed a re-entry program for ex-convicts in Massachusetts, and finally directed a maximum-security prison for violent juvenile offenders.[12]

As an attorney, Vachss represented only children and adolescents.[13] In addition to his private practice, he served as a law guardian in New York state. In every child abuse or neglect case,[14] state law requires the appointment of a law guardian, a lawyer who represents the child's interests during the legal proceedings.[15]

Writings

[edit]Andrew Vachss was the author of 33 novels and three collections of short stories, as well as poetry, plays, song lyrics, and graphic novels.[16] As a novelist, he was perhaps best known for his Burke series of hardboiled mysteries; Another Life[17] constituted the finale to the series.[18]

After completing the Burke novels, Vachss began two new series. Vachss released the first novel in the Dell & Dolly trilogy, entitled Aftershock, in 2013.[19] The second novel, Shockwave, was released in 2014,[20] and Signwave, the final book, was published in June 2015.[21] Departing from Vachss' familiar urban settings, the trilogy focuses on Dell, a former soldier and assassin, and Dolly, a former nurse with Doctors Without Borders and the love of Dell's life. While living in the Pacific Northwest, Dell and Dolly use their war-honed skills to maintain a "heads on stakes" barrier against the predators who use their everyday positions in the community as camouflage to attack the vulnerable.[22]

The Cross series uses distinctive supernatural aspects to further explore Vachss' argument that society's failure to protect its children is the greatest threat to the human species. In 2012, Vachss' published Blackjack: A Cross Novel,[23] featuring the mercenary Cross Crew, introduced in earlier Vachss short stories as Chicago's most-feared criminal gang. Urban Renewal, the second novel in the Cross series, came out in 2014.[24] The third in the series, Drawing Dead, was released in 2016.

In addition to the Aftershock, Burke, and Cross series, Vachss wrote several stand-alone works. The first novel he published outside the Burke series was Shella. Released in 1993, Shella was the most polarizing of his works in terms of critical response.[25] Vachss often referred to Shella as his "beloved orphan"[26] until the 2004 release of The Getaway Man,[27] a tribute to the Gold Medal paperback originals of the 1960s. In 2005, Vachss released the epic Two Trains Running,[28] a novel which takes place entirely during a two-week span in 1959, a critical period in American history. In form, Two Trains Running presents as a work composed entirely of transcribed surveillance tapes,[29] akin to a collage film constructed only of footage from a single source. His 2009 novel, Haiku,[30] focuses on the troubled lives of a band of homeless men in New York City, struggling to connect with and protect each other. In 2010, Vachss published two books: his novel The Weight,[31] is a noir romance involving a professional thief and a young widow in hiding. Heart Transplant,[32] an illustrated novel in an experimental design, tells the story of an abused and bullied young boy who finds his inner strength with the help of an unexpected mentor. That's How I Roll,[33] released in 2012, chronicles the death-row narrative of a hired killer as he reveals the secrets of his past, both horrifying and tender.

Vachss collaborated on works with authors Jim Colbert (Cross, 1995)[34] and Joe R. Lansdale (Veil's Visit, 1999).[35] He also created illustrated works with artists Frank Caruso (Heart Transplant, 2010)[36] and Geof Darrow (Another Chance to Get It Right, 1993;[37] The Shaolin Cowboy Adventure Magazine, 2014).[38] Vachss' graphic novel, Underground, was released in November 2014.[39]

Vachss also wrote non-fiction, including numerous articles and essays on child protection[40] and a book on juvenile criminology.[41] His books have been translated into 20 languages, and his shorter works have appeared in many publications, including Parade, Antaeus, Esquire, Playboy, and The New York Times.[42] Vachss' literary awards include the Grand Prix de Littérature Policière for Strega [as La Sorcière de Brooklyn]; the Falcon Award, Maltese Falcon Society of Japan, for Strega; the Deutscher Krimi Preis for Flood [as Kata]; and the Raymond Chandler Award for his body of work.

Andrew Vachss was a member of PEN and the Writers Guild of America. His autobiographical essay was added by invitation to Contemporary Authors in 2003.

Child protection

[edit]Many of Vachss' novels feature the shadowy, unlicensed investigator Burke, an ex-con, career criminal, and deeply conflicted character. About his protagonist, Vachss said:

If you look at Burke closely, you'll see the prototypical abused child: hypervigilant, distrustful. He's so committed to his family of choice—not his DNA-biological family, which tortured him, or the state which raised him, but the family that he chose—that homicide is a natural consequence of injuring any of that family. He's not a hit man. But he shares the same religion I do, which is revenge.

— Andrew Vachss, Horror Online, May 1999.[43]

Vachss coined the phrase "Children of the Secret", which refers to abused children, of whatever age, who were victimized without ever experiencing justice, much less love and protection.[44] In the Burke novels, some of these Children of the Secret have banded together as adults into what Vachss called a "family of choice".[45] Their connection is not biological, and they form very loyal bonds. Most are career criminals; none allows the law to come before the duty to family.

Vachss originated the term "Circle of Trust."[46] which has since entered general circulation. Vachss coined the term to combat the mistaken over-emphasis on "stranger danger,"[47] a bias that prevents society from focusing on the most common way children are accessed for victimization:

The biggest threat to children is always inside their houses. The predator with the ski-mask who grabs the kid out of a van, while a real thing, is a tiny percentage of those who prey upon children. Most victimization of children is within the Circle of Trust—not necessarily a parent, but somebody who was let into that circle, who can be a counselor, or a coach, or someone at a day-care center. The biggest danger to children is that they're perceived as property, not human beings.

— An Interview with Andrew Vachss, The AV Club, November 1996.[48]

Another term Vachss originated is "Transcenders."

I believe that many people who were abused as children do themselves—and the entire struggle—a disservice when they refer to themselves as "survivors." A long time ago, I found myself in the middle of a war zone. I was not killed. Hence, I "survived." That was happenstance ... just plain luck, not due to any greatness of character or heroism on my part. But what about those raised in a POW camp called "childhood?" Some of those children not only lived through it, not only refused to imitate the oppressor (evil is a decision, not a destiny), but actually maintained sufficient empathy to care about the protection of other children once they themselves became adults and were "out of danger." To me, such people are our greatest heroes. They represent the hope of our species, living proof that there is nothing bio–genetic about child abuse. I call them transcenders, because "surviving" (i.e., not dying from) child abuse is not the significant thing. It is when chance becomes choice that people distinguish themselves. Two little children are abused. Neither dies. One grows up and becomes a child abuser. The other becomes a child protector. One "passes it on." One "breaks the cycle." Should we call them both by the same name? Not in my book. (And not in my books, either.)[49]

Dogs

[edit]Another important theme that pervades Vachss' work is his love of dogs, particularly breeds considered "dangerous," such as Doberman pinschers, rottweilers, and especially pit bulls.[50] Throughout his writings,[51] Vachss asserted that with dogs, just as with humans, "you get what you raise."[52]

"There's a very specific formula for creating a monster," Vachss says. "It starts with chronic, unrelenting abuse. There's got to be societal notification and then passing on. The child eventually believes that what's being done is societally sanctioned. And after a while, empathy—which we have to learn, we're not born with it—cracks and dies. He feels only his own pain. There's your predatory sociopath." That's why Vachss posed for a recent publicity photo cradling his pit bull puppy. "You know what pit bulls are capable of, right?" he asks, referring to the animal's notorious killer reputation. "But they're also capable of being the most wonderful, sweet pets in the world, depending on how you raise them. That's all our children."

— "Unleashing the Criminal Mind," San Francisco Examiner, July 12, 1990.[53]

He was a passionate advocate against animal abuse such as dog-fighting,[54] and against breed-specific legislative bans.[55] With fellow crime writer James Colbert, Vachss trained dogs to serve as therapy dogs for abused children. The dogs have a calming effect on traumatized children. Vachss noted that using these particular breeds further increases the victims' feelings of security; their "dangerous" appearance, in combination with the extensive therapy training, makes them excellent protection against human threats.[56] During her time as chief prosecutor, Alice Vachss regularly brought one such trained dog, Sheba, to work with abused children being interviewed at the Special Victims Bureau.[57]

Personal life

[edit]When Vachss was 7 years old, an older boy swung a chain at his right eye. The resulting injuries damaged the eye muscles and resulted in his wearing an eyepatch.[58] According to Vachss, removing it had the effect of a strobe light flashing in his face. Vachss also had a small blue heart tattooed on his right hand.[59]

Vachss' wife, Alice, was a sex crimes prosecutor, and she later became Chief of the Special Victims Bureau in Queens, New York. She is the author of the nonfiction book Sex Crimes: Ten Years on the Front Lines Prosecuting Rapists and Confronting Their Collaborators, a New York Times Notable Book of the Year.[60] She has continued her work as Special Prosecutor for Sex Crimes in rural Oregon.[61]

He died of coronary artery disease on November 23, 2021, at the age of 79 at his residence in Pacific Northwest.[62][63]

Honors and awards

[edit]Professional honors and awards

[edit]- A/V Peer Review (highest rating) by Martindale-Hubbell[64]

- 2004, LL.D. (Hon.) Case Western Reserve University[65]

- 2003, First Annual Harvey R. Houck Award (Justice for Children)

- 2003, First Annual Illuminations Award (St. Vincent's Center National Child Abuse Prevention Program)

- 1994, Childhelp Congressional Award[66]

- 1976, John Hay Whitney Foundation Fellow

- 1970, Industrial Areas Foundation Training Institute Fellow

Literary honors and awards

[edit]- 2000, Raymond Chandler Award, Giurìa a Noir in Festival, Courmayeur, Italy, for body of writing[67]

- 1989, Deutscher Krimi Preis, Die Jury des Bochumer Krimi Archivs, Germany, for Flood (as Kata)

- 1989, Maltese Falcon Award, Japan, for Strega

- 1988, Grand Prix de Littérature Policière, France, for Strega (as La Sorciere de Brooklyn)

Bibliography

[edit]The Burke series

[edit]- Flood (1985)

- Strega (1987)

- Blue Belle (1988)

- Hard Candy (1989)

- Blossom (1990)

- Sacrifice (1991)

- Down in the Zero (1994)

- Footsteps of the Hawk (1995)

- False Allegations (1996)

- Safe House (1998)

- Choice of Evil (1999)

- Dead and Gone (2000)

- Pain Management (2001)

- Only Child (2002)

- Down Here (2004)

- Mask Market (2006)

- Terminal (2007)

- Another Life (2008)

The Cross series

[edit]- Blackjack: A Cross Novel (2012)

- Urban Renewal: A Cross Novel (2014)

- Drawing Dead: A Cross Novel (2016)

The Aftershock trilogy

[edit]- Aftershock (2013)

- Shockwave (2014)

- Signwave (2015)

Other novels

[edit]- Shella (1993)

- Batman: The Ultimate Evil (1995)

- The Getaway Man (2003)

- Two Trains Running (2005)

- Haiku (2009)

- The Weight (2010)

- A Bomb Built in Hell (2012; set in the Burke universe, originally written in 1973 but refused by publishers on grounds of being "too violent"; first published as a German translation, Eisgott, in 2003)

- That's How I Roll (2012)

- Carbon (2019)

- Blood Line (2022)

Novelettes

[edit]- The Questioner (2018)

Short story collections

[edit]- Born Bad (1994)

- Everybody Pays (1999)

- Proving It (2001) audiobook collection.

- Dog Stories – online collection.

- Mortal Lock (2013)

Comic books and graphic novels

[edit]- Hard Looks (1992–93) – ten-issue series.

- Andrew Vachss' Underground (1993–1994) – four-issue series of illustrated and non-illustrated short stories. Contains Vachss' "Underground" stories (that are also featured in Born Bad), as well as stories by other authors that exist within Vachss' "Underground" world.

- Batman: The Ultimate Evil (1995) – two-issue adaptation of the novel.

- Cross (1995) – seven-issue series with James Colbert.

- Predator: Race War (1993) – five-issue series; (1995) collected edition.

- Alamaailma (1997) – Finnish graphic novel, illustrating two of the "Underground" short stories from Born Bad.

- Hard Looks (1996, 2002) – trade paperback.

- Another Chance To Get It Right: A Children's Book for Adults (1993, 1995) (reprinted with additional material and new cover, 2003, 2016)

- Heart Transplant (2010)

- Underground (2014)

Plays

[edit]- Placebo (in Antaeus, 1991)

- Warlord (in Born Bad, 1994)

- Replay (in Born Bad, 1994)

Non-fiction

[edit]- The Life-Style Violent Juvenile: The Secure Treatment Approach (Lexington, 1979)

- The Child Abuse-Delinquency Connection — A Lawyer's View (Lexington, 1989)

- Parade Magazine articles (1985–2006)

References

[edit]- ^ "Pronunciation of "Vachss"". Vachss.com. July 16, 1993. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ Dullea, Georgia (June 17, 1988). "The Law: Taking on Children as Clients". The New York Times. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ Rovner, Sandy (May 27, 1987). "In Defense of the Children Lawyer Andrew Henry Vachss, Fighting Urban Evil With Fiction". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 5, 2019.

- ^ "Andrew Vachss, The Zero". Vachss.com. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ "Andrew Vachss Does Not Paint Pretty Pictures". CNN. Reuters. November 9, 2000. Archived from the original on September 4, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ a b "Andrew Vachss: Beating the Devil". Gallery Magazine. April 2000. Retrieved February 2, 2012 – via Vachss.com.

- ^ "Andrew Vachss: Hot Biafra Nights". Mumblage. September 2000. Retrieved February 2, 2012 – via Vachss.com.

- ^ "Nigeria Bans Red Cross Aid to Biafra'". BBC News. June 30, 1985. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ "The Secession That Failed". Time. January 26, 1970. Archived from the original on April 10, 2009. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ "One Sole Practitioner's Crusade: Best-Selling Novelist Has Declared War On Child Abusers". Lawyers Weekly USA. November 25, 2002. Retrieved February 2, 2012 – via Vachss.com.

- ^ "Testimony of Andrew Vachss, U.S. National Commission on Libraries and Information Science". November 10, 1998. Retrieved February 2, 2012 – via Vachss.com.

- ^ "Andrew Vachss, Contemporary Authors, 2003". Vachss.com. March 4, 1983. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ "Andrew Vachss: Guidelines for Acceptance of a Child's Case". Vachss.com. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ McKinney's Cons. Laws of NY, Book 29A, Family Ct. Act §§ 241–249.

- ^ Under New York law, a law guardian also must be appointed in delinquency cases. At the judge's discretion, a law guardian may be appointed for a child in a custody dispute.

- ^ "Index of author's written works". Vachss.com. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- ^ "Finale of Burke series". Vachss.com. February 28, 2011. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ "US publication date of Another Life". Vachss.com. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ "Aftershock by Andrew Vachss". THE ZERO. vachss.com. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- ^ "Shockwave by Andrew Vachss". THE ZERO. vachss.com. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- ^ "Signwave by Andrew Vachss". THE ZERO. vachss.com. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- ^ "Aftershock by Andrew Vachss, reviewed by Sons of Spade". Sons of Spade. July 8, 2014. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- ^ "Blackjack: A Cross Novel". Vachss.com. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ "Urban Renewal: A Cross Novel". Vachss.com. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- ^ "Shella". Vachss.com. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ "The World As They See It: Andrew Vachss". Vachss.com. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ "The Getaway Man". Vachss.com. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ "Two Trains Running". Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ "Reinventing Vachss, by Adam Dunn". Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ "Haiku". Vachss.com. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ "The Weight". Vachss.com. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ "Heart Transplant". Vachss.com. October 19, 2010. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ "That's How I Roll". Vachss.com. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ^ "Cross (graphic series)". Vachss.com. May 18, 2012. Retrieved May 18, 2012.

- ^ "Veil's Visit". Vachss.com. May 18, 2012. Retrieved May 18, 2012.

- ^ "Heart Transplant". Vachss.com. May 18, 2012. Retrieved May 18, 2012.

- ^ "Another Chance to Get It Right". Vachss.com. May 18, 2012. Retrieved May 18, 2012.

- ^ "The Shaolin Cowboy Adventure Magazine". vachss.com. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ "Underground". bleedingcool.com. October 27, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ^ "Articles and essays on child protection". Vachss.com. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "On designing prisons for violent youth, Andrew Vachss interview, 2009". Youtube.com. February 17, 2009. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ "Magazines". Twotrainsrunning.com. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ ""Andrew Vachss: A Man Who Will Die Trying", by Paula Guran, Horror Online, May 1999". Darkecho.com. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ "Children of the Secret". Vachss.com. November 13, 1995. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Andrew Vachss discusses his use of "family of choice", Family of Choice webcast, January 14, 2009". Youtube.com. February 17, 2009. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ "Abuse within the Circle of Trust". Vachss.com. 2011. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ "Andrew Vachss Doesn't Fight Fair: A Conversation with Clayton Moore". Vachss.com. February 24, 2003. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ ""An Interview with Andrew Vachss," by John Krewson". Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ "Survivors and Transcenders".

- ^ ""A Conversation with Andrew Vachss," Blur Magazine, March 1997". Vachss.com. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ "Dog stories". Vachss.com. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ Ski apps (January 19, 2009). ""Goodbye Burke, Hello Andrew," The Independent, January 19, 2009". Independent.ie. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ ""Unleashing the Criminal Mind," San Francisco Examiner, July 12, 1990". Vachss.com. July 12, 1990. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ ""Dead Game," by Andrew Vachss". Vachss.com. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- ^ "Breed-specific legislation". Vachss.com. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ "Training assistance dogs for child protection proceedings". Vachss.com. November 4, 1994. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ "Sheba, child protection assistance dog". Vachss.com. November 12, 1989. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ Rahner, Mark "Vachss' Work Emanates From His Own Cold Rage" Seattle Times (October 15, 2000). Retrieved on 3-09-14.

- ^ Dundas, Zach "The Haunted World of Andrew Vachss" Willamette Week (November 17, 1999). Retrieved on 2-09-13.

- ^ "Alice Vachss website". Alicevachss.com. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ "Sex Crimes: Then and Now". alicevachss.com. May 1, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ Genzlinger, Neil (January 16, 2022). "Andrew Vachss, Children's Champion in Court and Novels, Dies at 79". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ "Vachss.com". Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- ^ "A/V Martindale-Hubbell rating".

- ^ "LL.D (honoris causa) Case Western University, 2004".

- ^ "Childhelp Congressional Award, 1994".

- ^ "Raymond Chandler Award, 2000".

External links

[edit]- 1942 births

- 2021 deaths

- 20th-century American novelists

- 21st-century American novelists

- American crime fiction writers

- American graphic novelists

- American legal writers

- American male novelists

- Bob Clampett Humanitarian Award winners

- Case Western Reserve University alumni

- Child abuse

- Lawyers from New York City

- Maltese Falcon Award winners

- Writers from Manhattan

- American male essayists

- People of the Nigerian Civil War

- American expatriates in Nigeria

- American male short story writers

- 20th-century American short story writers

- 21st-century American short story writers

- 21st-century American essayists

- 20th-century American male writers

- 21st-century American male writers

- Novelists from New York (state)

- 20th-century American essayists

- Eyepatch wearers