Andy Beshear

Andy Beshear | |

|---|---|

Beshear in 2024 | |

| 63rd Governor of Kentucky | |

| Assumed office December 10, 2019 | |

| Lieutenant | Jacqueline Coleman |

| Preceded by | Matt Bevin |

| 50th Attorney General of Kentucky | |

| In office January 4, 2016 – December 10, 2019 | |

| Governor | Matt Bevin |

| Preceded by | Jack Conway |

| Succeeded by | Daniel Cameron |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Andrew Graham Beshear November 29, 1977 Louisville, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives |

|

| Residence | Governor's Mansion |

| Education | |

| Signature |  |

| Website | Government website |

Andrew Graham Beshear (/bəˈʃɪər/ bə-SHEER;[1] born November 29, 1977) is an American attorney and politician serving since 2019 as the 63rd governor of Kentucky. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as the 50th attorney general of Kentucky from 2016 to 2019.[2] He is the son of former Kentucky governor Steve Beshear.

As attorney general, Beshear sued Governor Matt Bevin several times over issues such as pensions and defeated Bevin by just over 5,000 votes in the 2019 gubernatorial election. Beshear was reelected to a second term in 2023 by a wider margin of 5%.[3] As of 2024, he and Lieutenant Governor Jacqueline Coleman are the only current Democratic statewide elected officials in Kentucky.

Early life and education

[edit]Beshear was born in Louisville, Kentucky,[4][5] the son of Jane Beshear (née Mary Jane Klingner) and Steve Beshear.[6] He was raised in Lexington and graduated from Henry Clay High School.[4][7] His father, a lawyer and politician, was the governor of Kentucky from 2007 to 2015.[8]

After high school, Beshear studied political science and anthropology at Vanderbilt University, where he was a member of the Sigma Chi Fraternity. He graduated in 2000 with a Bachelor of Arts, magna cum laude.[9][10] He then attended the University of Virginia School of Law, receiving a Juris Doctor in 2003.[11]

Legal career

[edit]Beshear was a 2001 summer associate at White & Case LLP in New York, the same law firm where his father started his law career.[12] Beshear worked at White & Case in Washington D.C. for two years after his graduation from UVA law.[13] In 2005, he was hired by the law firm Stites & Harbison, where his father was a partner.[14][15][16] He represented the developers of the Bluegrass Pipeline, which would have transported natural gas liquid through Kentucky. The project was controversial; critics voiced environmental concerns and objections to the use of eminent domain for the pipeline. His father's office maintained that there was no conflict of interest with the son's representation.[17][18][19][20] Beshear also represented the Indian company UFlex, which sought $20 million in tax breaks from his father's administration, drawing criticism from ethics watchdogs over a potential conflict of interest.[21] In 2013, while he was working at Stites & Harbison, Lawyer Monthly named Beshear its "Consumer Lawyer of the Year – USA".[22]

Kentucky Attorney General (2016–2019)

[edit]2015 election

[edit]

- 50–60%

- 60–70%

- 50–60%

- 60–70%

- 70–80%

- 80–90%

In November 2013, Beshear announced his candidacy in the 2015 election for Attorney General of Kentucky, to succeed Democrat Jack Conway, who could not run for reelection, due to term limits.[23][24]

Beshear defeated Republican Whitney Westerfield with 50.1% of the vote to Westerfield's 49.9%.[25][26] The margin was approximately 2,000 votes.[27]

Tenure

[edit]

Beshear sued Governor Matt Bevin several times over what he argued was Bevin's abuse of executive powers during Beshear's tenure as attorney general and while he was campaigning against Bevin for governor.[28] Beshear won some cases and lost others.[28] In April 2016, he sued Bevin over his mid-cycle budget cuts to the state university system.[29] The Kentucky Supreme Court issued a 5–2 ruling agreeing with Beshear that Bevin lacked the authority to make mid-cycle budget cuts without the Kentucky General Assembly's approval.[30] Also in 2016, the Kentucky Supreme Court unanimously sided with Bevin when Beshear sued him on the grounds that Bevin lacked the authority to overhaul the University of Louisville's board of trustees.[31] In 2017, the Kentucky Supreme Court dismissed a lawsuit Beshear brought against Bevin, holding that Bevin had the power to temporarily reshape boards while the legislature is out of session; Bevin called Beshear's lawsuit a "shameful waste of taxpayer resources".[32] In April 2018, Beshear successfully sued Bevin for signing Senate Bill 151, a controversial plan to reform teacher pensions, with the Kentucky Supreme Court ruling the bill unconstitutional.[33][34][35] Bevin said Beshear "never sues on behalf of the people of Kentucky. He does it on behalf of his own political career".[36]

In October 2019, Beshear filed nine lawsuits against pharmaceutical companies for their alleged involvement in fueling Kentucky's opioid epidemic.[37][38]

Beshear forwent a run for a second term as attorney general to run for governor against Bevin. He resigned from the attorney general's office on December 10, 2019, before his inauguration as governor the same day.[2] By executive order, Beshear appointed Attorney General-elect Daniel Cameron to serve the remainder of his term.[39][40][41] Cameron was Kentucky's first African-American attorney general[42] and unsuccessfully ran for governor against Beshear in 2023.[3]

Governor of Kentucky (2019–present)

[edit]Elections

[edit]2019

[edit]

- 40–50%

- 50–60%

- 60–70%

- 40–50%

- 50–60%

- 60–70%

- 70–80%

On July 9, 2018, Beshear declared his candidacy for the Democratic nomination for governor of Kentucky in the 2019 election.[43] He chose Jacqueline Coleman, a nonprofit president, assistant principal, and former state house candidate, as his running mate.[44] Beshear said he would make public education a priority.[34] In May 2019, he won the Democratic nomination with 37.9% of the vote in a three-way contest.[45][46][47]

Beshear faced incumbent Governor Matt Bevin, the nation's least popular governor, in the November 5 general election.[48][49][50] He defeated Bevin with 49.20% of the vote to Bevin's 48.83%.[51] It was the closest Kentucky gubernatorial election ever by percentage, and the closest race of the 2019 gubernatorial election cycle.[52][53]

Days later, Bevin had not yet conceded the race, claiming large-scale voting irregularities. Kentucky Secretary of State Alison Lundergan Grimes's office nevertheless declared Beshear the winner.[51][54] On November 14, Bevin conceded the election after a recanvass was performed at his request that resulted in just a single change, an additional vote for a write-in candidate.[55]

Beshear defeated Bevin largely by winning the state's two most populous counties, Jefferson and Fayette (respectively home to Louisville and Lexington), by an overwhelming margin, taking over 65% of the vote in each. He also narrowly carried the historically heavily Republican suburban counties of Campbell and Kenton in Northern Kentucky, as well as several historically Democratic rural counties in Eastern Kentucky that had swung heavily Republican in recent elections.

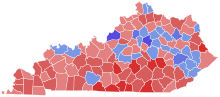

2023

[edit]

- 50–60%

- 60–70%

- 70–80%

- 50–60%

- 60–70%

- 70–80%

On October 1, 2021, Beshear declared his candidacy for reelection as governor in the 2023 election.[56] He defeated perennial candidates Peppy Martin and Geoff Young in the Democratic primary election, receiving over 90% of the vote.[57]

On November 7, 2023, Beshear defeated Republican nominee Daniel Cameron by a margin of 52.53% to 47.46% in the 2023 Kentucky gubernatorial election, winning reelection to a second term.[58][59]

Beshear's victory has been attributed to his broad popularity among Democrats and independents, as well as approximately half of Republicans in the state.[60] Compared to 2019, Beshear most improved his performance in suburban precincts; he increased his margins by nearly six percentage points in suburban areas, compared to 4.5 percentage points in urban and rural precincts.[61] In addition, Republican leadership credited a viral ad featuring Hadley Duvall, whose stepfather raped and impregnated her when she was 12, for contributing to Beshear's victory, as they noted that Republicans won the down-ballot races. Kentucky was one of 12 states that had anti-abortion laws that allowed no exceptions for rape or incest, which Cameron initially supported before saying he was open to exceptions.[62]

Tenure

[edit]

Beshear was inaugurated as governor on December 10, 2019.[63] In his inaugural address, he called on Republicans, who had a supermajority in both houses of the Kentucky General Assembly, to reach across the aisle and solve Kentucky's issues in a bipartisan way.[64]

Upon taking office, Beshear replaced all 11 members of the Kentucky Board of Education before the end of their two-year terms. The firing of the board members fulfilled a campaign pledge and was an unprecedented use of the governor's power to reorganize state boards while the legislature was not in session. Beshear's critics suggested that the appointments undermined the Kentucky Education Reform Act of 1990, which sought to insulate the board from political influence; the Board had increasingly been the focus of political battles in the years preceding 2019.[65]

On December 12, 2019, Beshear signed an executive order restoring voting rights to 180,315 Kentuckians, who he said were disproportionately African American who had been convicted of nonviolent felonies.[66][67][68][69]

In April 2020, Beshear ordered Kentucky state troopers to record the license plate numbers of churchgoers who violated the state's COVID-19 stay-at-home order to attend in-person Easter Sunday church services.[70][71] The order led to contentious debate.[72]

In June 2020, Beshear promised to provide free health care to all African-American residents of Kentucky who need it in an attempt to resolve health care inequities that came to light during the COVID-19 pandemic.[73][74][75]

On November 18, 2020, as the state's COVID-19 cases continued to increase, Beshear ordered Kentucky's public and private schools to halt in-person learning on November 23 with in-person classes to resume in January 2021. This marked the first time Beshear ordered, rather than recommended, schools to cease in-person instruction.[76][77][78] Danville Christian Academy, joined by Attorney General Daniel Cameron, filed a lawsuit in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky, claiming that Beshear's order violated the First Amendment by prohibiting religious organizations to educate children in accordance with their faith.[79] A group of Republican U.S. senators supported the challenge.[77] The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit and the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Beshear's order.[77][80]

In March 2021, Beshear vetoed all or part of 27 bills that the Kentucky legislature had passed. The legislature overrode his vetoes.[81]

Beshear's tenure in office has been marked by several natural disasters. In December 2021, Beshear led the emergency response to a tornado outbreak in western Kentucky, which devastated the town of Mayfield and killed more than 70 people, making it the deadliest in the state's history.[82] In July 2022, torrential rain caused severe flooding across Kentucky's Appalachia region and led to the deaths of over 25 people; Beshear worked with the federal government to coordinate search and rescue missions as President Biden declared a federal disaster to direct relief money to the state.[83][84]

In 2024, Beshear created a political action committee to raise money for candidates in the 2024 United States elections who "push back against this national trend of anger politics and division".[85]

Political positions

[edit]Abortion

[edit]Beshear supports access to abortion and Roe v. Wade.[86] One month after he took office as governor, his administration gave Planned Parenthood permission to provide abortions at its Louisville clinic, making it the second facility in Kentucky to offer abortions.[87] In April 2020, Beshear vetoed a bill that would have allowed Attorney General Daniel Cameron to suspend abortions during the COVID-19 pandemic and exercise more power regulating clinics that offer abortions.[88][89] He was endorsed by Reproductive Freedom for All, an abortion-rights group, and is supported by Planned Parenthood.[88][90]

In 2021, Beshear allowed a born-alive bill to become law without his signature, requiring doctors to provide medical care for any infant born alive, including those born alive due to a failed abortion procedure.[91]

COVID-19

[edit]

On March 25, 2020, Beshear declared a state of emergency over the COVID-19 pandemic.[92] He encouraged business owners to require customers to wear face coverings while indoors.[93][94] He also banned "mass gatherings" including protests but not normal gatherings at shopping malls and libraries; constitutional law professor Floyd Abrams and lawyer John Langford opined that Beshear's order was inappropriate as it violated public protests' special protected status under the First Amendment.[95]

In August 2020, Beshear signed an executive order releasing inmates from overcrowded prisons and jails in an effort to slow the virus's spread. The Kentucky Department of Information and Technology Services Research and Statistics found that over 48% of the 1,704 inmates released committed a crime within a year of their release and that a third of those were felonies.[96]

Beshear was criticized for not calling the Kentucky General Assembly into a special session (a power only the governor has) in order to work with state representatives to better address the needs of their constituents during the pandemic.[97] In November 2020, the Kentucky Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of Beshear's emergency executive orders.[98] In late November 2020, Beshear imposed new restrictions to further slow the spread of COVID-19, including closing all indoor service for restaurants and bars, restricting in-person learning at schools, limiting occupancy at gyms, and limiting social gatherings.[99] House Speaker David Osborne and Senate President Robert Stivers criticized Beshear for failing to consult the legislature before making his decisions.[100]

Beshear's targeted closures were criticized after it was discovered that state and local authorities were unable to establish contact tracing as it relates to certain types of businesses listed in his restrictions.[101] On June 11, 2021 – one day after the Kentucky Supreme Court heard oral argument on the emergency powers issue – Beshear lifted most of Kentucky's COVID-19 restrictions.[102][103][104][105][106] In August 2021, amid an upsurge in cases driven by the Delta variant, Beshear mandated that face masks be worn in public schools.[107]

On August 19, 2021, U.S. District Judge William Bertelsman issued a temporary restraining order blocking the school mask mandate.[108] Two days later, the Kentucky Supreme Court ruled against Beshear's challenge of several newly enacted Kentucky laws that, among other things, limit the governor's authority to issue executive orders in times of emergency to 30 days, unless extended by state legislators. The state supreme court dissolved an injunction against the law issued by a Kentucky trial court at Beshear's request. The Supreme Court's opinion, by Justice Lawrence VanMeter, addressed separation of powers between the governor and the General Assembly. The Kentucky Supreme Court found that the challenged laws were valid exercises of the General Assembly's legislative powers, although two justices wrote in a concurring opinion that the 30-day "kill switch" enacted by the legislature should be scrutinized on remand to the lower courts.[109][110] On August 23, 2021, Beshear rescinded his executive order requiring masks in Kentucky schools.[111]

Crime

[edit]Beshear signed an executive order completely restoring the voting rights, and right to hold public office, of 180,315 Kentuckians who had been convicted of nonviolent felonies.[68][112][113][67] He has restored rights to more felons than any other governor in American history.[67]

In March 2021, Beshear signed a law that allows judges to decide whether to transfer minors 14 and older to adult court if they are charged with a crime involving a firearm. Previously, judges were required to send juveniles to adult court to be prosecuted for a felony if a firearm was involved.[114]

Also in March 2021, after the Kentucky legislature passed a bill to make it a crime to cause $500 or more damage to a rental property, Beshear vetoed the bill.[115] The Kentucky House (74–18) and Senate (28–8) overrode his veto.[115]

Beshear has said he supports the death penalty.[116]

Drugs

[edit]

Beshear said that a significant driver of incarceration in Kentucky is the drug epidemic, and opined that Kentucky "must reduce the overall size of our incarcerated population... We don't have more criminals. We just put more people in our prisons and jails."[117]

Beshear is of the view that possession of cannabis should never result in incarceration.[118] He supported legalization of medical cannabis.[119][120] In November 2022, Beshear signed an executive order to allow medical marijuana possession and to regulate delta-8-THC.[121] On March 31, 2023, he signed SB 47, which established a medical cannabis program in Kentucky.[122]

Economic policy

[edit]In 2019, Beshear pledged to bring more advanced manufacturing jobs and health care jobs to Kentucky, to offset job losses due to the decline of coal.[123]

Beshear opposes the Kentucky right-to-work law.[124][64]

After the Kentucky legislature voted to allow distilleries and breweries to qualify for a sales tax break on new equipment, Beshear vetoed the provision. In April 2020, the Kentucky legislature overrode the veto.[125]

In June 2021, Beshear signed an executive order to allow college athletes to receive name, image, and likeness compensation. It made Kentucky the first state to do so via executive order; six other states had done so through legislation.[126][127]

Education

[edit]In 2019, Beshear pledged to include a $2,000 pay raise for all Kentucky teachers in his budgets (at what he estimated would be a cost of $84 million). Republican House Majority Floor Leader John Carney rejected the proposal.[128][86][129] Beshear has proposed such a pay raise in his budgets, but the Kentucky legislature has not included such raises in the budgets it passed.[64][130]

Beshear is opposed to all charter schools in Kentucky, saying "schools run by corporations are not public schools." He says that funding them would violate the state constitution.[131]

Environment

[edit]Beshear accepts the scientific consensus on climate change. In 2019, he said he wanted to create more clean energy jobs to employ those who lose their jobs in the coal industry and to expand clean coal technology in Kentucky.[132]

Gambling

[edit]Beshear supports legalizing casino gambling, sports betting, fantasy sports betting, and online poker betting in Kentucky.[133][134] Beshear proclaimed March 2020 Responsible Gambling Awareness Month in Kentucky.[135] On March 31, 2023, Beshear signed House Bill 551 into law, legalizing sports betting in Kentucky.[136]

Gun rights

[edit]Beshear said he would not support an assault weapons ban. He said he would instead support a red flag law authorizing courts to allow police to temporarily confiscate firearms from people a judge deemed a danger to themselves or others.[133]

On April 10, 2023, a personal friend of Beshear's was killed by gunfire in the Louisville bank shooting.[137][138]

Health care

[edit]Beshear supports Kentucky's Medicaid expansion, which provides affordable health care to over 500,000 Kentuckians, including anyone with a preexisting condition. He criticized Bevin for trying to roll back the state's Medicaid expansion (which ultimately failed). As attorney general and governor, Beshear expressed support for the Affordable Care Act and criticized efforts to strike the law down in the courts.[132] On October 5, 2020, he announced the relaunch and expansion of kynect, the state health insurance marketplace that was started in 2013 during Steve Beshear's term as governor and dismantled by Bevin in 2017.[139]

Immigration

[edit]In December 2019, Beshear told President Donald Trump's administration that he planned to have Kentucky continue to accept refugees under the U.S. immigration program.[140] Trump had told state governments that they had the power to opt out of the U.S. refugee resettlement program.[140]

Infrastructure

[edit]Beshear supports a $2.5-billion project to build a companion bridge to supplement the Brent Spence Bridge that carries Interstates 71 and 75 over the Ohio River between Covington, Kentucky, and Cincinnati, Ohio.[141] He hoped to fund the bridge by conventional means, not tolling, but was unsure whether the state in fact had the funds to do that.[142] In 2021, Kentucky Senator Chris McDaniel, Northern Kentucky's top Republican state lawmaker and chair of the Senate finance and budget committee, said he opposed Beshear's proposal to use the state's rainy day fund or a general fund surplus to help pay for the project.[143]

In August 2019, Beshear promised to construct the Interstate 69 Ohio River Bridge between Henderson, Kentucky, and Evansville, Indiana, by 2023, saying, "we will build that I-69 bridge in my first term as governor."[144] The project would cost $914 million (plus financing and interest costs).[144] He said he believed the project would provide economic benefits to Western Kentucky.[145]

LGBT rights

[edit]Beshear supports legal same-sex marriage. He also supports nondiscrimination laws that include gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people.[146] He was the first sitting governor of Kentucky to attend a rally staged by the Fairness Campaign, and he supports banning the practice of conversion therapy for LGBTQ youth.[147] In 2024, he signed an executive order to ban conversion therapy for minors after Republicans in the state legislature had repeatedly blocked legislative efforts to do so.[148] In March 2023, Beshear vetoed a bill that would create new regulations and restrictions for transgender youth, including a ban on gender-affirming care; the Republican-dominated legislature overrode his veto.[149] Beshear also showed support for a group of drag queens he took a selfie with and strongly defended his actions when criticized by Republicans.[150]

Pensions

[edit]Beshear wants to fund the state's pension system, which has accumulated $24 billion in debt since 2000, the most of any state in the country.[citation needed] He opposed pension cuts made by Bevin, and said he wants to guarantee all workers pensions when they retire.[132] As of June 30, 2020, the Kentucky State Pension Fund was at 58.8% of its obligations for the coming decades.[151]

Personal life

[edit]Beshear and his wife Britainy are deacons at the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) denominated Beargrass Christian Church in Louisville.[152][153] They have two children.[15]

Publications

[edit]Articles

[edit]- "How Democrats can win, everywhere", The Washington Post, November 25, 2019 (co-authored with John Bel Edwards)[154]

- "I'm the Governor of Kentucky. Here's How Democrats Can Win Again", New York Times, November 12, 2024[155]

Electoral history

[edit]2015

Beshear ran unopposed in the 2015 Democratic primary for Kentucky attorney general.[156]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Andy Beshear | 479,929 | 50.1% | |

| Republican | Whitney Westerfield | 477,735 | 49.9% | |

| Total votes | 957,664 | 100.0% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

2019

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Andy Beshear | 149,438 | 37.9% | |

| Democratic | Rocky Adkins | 125,970 | 31.9% | |

| Democratic | Adam Edelen | 110,159 | 27.9% | |

| Democratic | Geoff Young | 8,923 | 2.3% | |

| Total votes | 394,490 | 100.0% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Andy Beshear | 709,577 | 49.20% | |

| Republican | Matt Bevin (incumbent) | 704,388 | 48.83% | |

| Libertarian | John Hicks | 28,425 | 1.97% | |

| Total votes | 1,442,390 | 100.0% | ||

| Democratic gain from Republican | ||||

2023

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Andy Beshear (incumbent) | 176,589 | 91.3% | |

| Democratic | Geoff Young | 9,865 | 5.1% | |

| Democratic | Peppy Martin | 6,913 | 3.6% | |

| Total votes | 193,367 | 100.0% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Andy Beshear (incumbent) | 694,167 | 52.5% | |

| Republican | Daniel Cameron | 627,086 | 47.4% | |

| Total votes | 1,321,253 | 100.0% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Done. Andy Beshear for Kentucky. October 10, 2019. Event occurs at 00:17. Retrieved August 20, 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b Desrochers, Daniel (December 10, 2019). "It's official: Andy Beshear sworn in as 63rd governor of Kentucky at midnight". Lexington Herald-Leader. Archived from the original on December 11, 2019. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- ^ a b Bowman, Bridget (November 7, 2023). "Democratic Governor Andy Beshear Wins Re-Election in Kentucky". NBC News. Archived from the original on November 8, 2023. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Horn, Austin; Starkey, Jackie (July 21, 2024). "Who is Andy Beshear? Kentucky's governor is on list of possible Democratic VP nominees". Lexington Herald-Leader. Archived from the original on July 25, 2024. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ Jones, Michael L. (September 30, 2022). "Forty Under 40 Hall of Famer: How Kentucky's governor kept his head in the middle of multiple crises". Louisville Business First. Archived from the original on September 30, 2022. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ Moore, Josh (September 7, 2017). "Former Kentucky first lady, pro ball player among Henry Clay Hall of Fame inductees". Lexington Herald-Leader. Archived from the original on November 9, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ Andy Beshear (October 8, 2019). "[I'm] especially proud to be a Henry Clay High School graduate!", Twitter.

- ^ "The Kentucky Attorney General". ag.ky.gov. Archived from the original on August 5, 2019. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ^ "And the Beat Goes On: A resilient Vanderbilt community finds innovative ways to thrive amid the challenges of COVID-19". Vanderbilt University. May 14, 2020. Archived from the original on November 16, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ^ "Luncheon". Sigma Chi Alumni Chapter – Louisville, KY. Archived from the original on November 24, 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ Eric Williamson (April 9, 2020). "Andy Beshear '03 Leads as Governor of Kentucky". University of Virginia School of Law. Archived from the original on November 16, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ^ Wagar, Kit (October 20, 1996). "2 Political Veterans Seek Senate Post; Beshear Stresses Traditional Concerns of Democrats: Health Care, Education". Lexington Herald-Leader.

- ^ Loftus, Tom (July 9, 2018). "Here are 10 things to know about Andy Beshear, candidate for governor". The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on July 27, 2024. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ^ "Former Gov. Returning To Work For Law Firm". WTVF. January 14, 2016. Archived from the original on November 16, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ^ a b Cheves, John (October 17, 2015). "Profile: Meet Andy Beshear, the Democratic nominee for attorney general". Lexington Herald-Leader. Archived from the original on October 21, 2015. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- ^ Cheves, John (October 19, 2015). "Beshear taps father's network in AG run". Lexington Herald-Leader. Archived from the original on March 23, 2017. Retrieved November 3, 2015 – via The Paducah Sun.

- ^ "Proposed Natural Gas Liquids Pipeline Opponents Deliver Petition to KY Governor". WKMS-FM. November 5, 2013. Archived from the original on November 25, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2021.

- ^ Peterson, Erica (September 23, 2013). "Beshear Says He Still Believes Bluegrass Pipeline Issues Can Wait Until January". 89.3 WFPL News Louisville. Archived from the original on November 25, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2021.

- ^ Bruggers, James (August 2, 2013). "Kentucky Governor Steve Beshear's son working for Bluegrass Pipeline developers". The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on April 15, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- ^ Quinn, Ryan (August 1, 2013). "Beshear's Son Representing Controversial Pipeline Company". The State Journal.

- ^ Cheves, John (November 23, 2011). "Gov. Beshear's son represents company seeking tax breaks from state". Lexington Herald-Leader. Archived from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2021.

- ^ "Andy Beshear named 2013 U.S. Consumer Lawyer of the Year". Lane Report. October 1, 2013. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ "Andy Beshear Announces Bid for Kentucky Attorney General". WFPL. November 14, 2013. Archived from the original on July 26, 2014. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- ^ Wheatley, Kevin (October 3, 2013). "Andy Beshear breaks fundraising record for down-ballot 2015 race". cn|2. Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ^ Loftus, Tom (November 3, 2015). "Andy Beshear prevails for attorney general". The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved December 15, 2015.

- ^ Smith, Lawrence (November 10, 2015). "Democratic Attorney General-elect Andy Beshear pledges cooperation". WDRB. Archived from the original on December 21, 2015. Retrieved December 15, 2015.

- ^ Kelly, Cozen O'Connor-JB; Rutherford, Blake S. (November 5, 2015). "The State AG report weekly update November 5, 2015". Lexology. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ a b "Andy Beshear Overplaying Court Victories Against Matt Bevin". The Courier-Journal. June 19, 2019. Archived from the original on April 26, 2023. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ Loftus, Tom (April 11, 2016). "AG Beshear sues to reverse Bevin university cuts". The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved April 11, 2016.

- ^ "Ky. Supreme Court Rules Bevin Can't Cut Budget of Public Colleges, Universities". WKYT-TV. September 21, 2016. Archived from the original on September 23, 2016. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ Barton, Ryland (December 9, 2019). "Gov.-Elect Beshear's Board Of Education Overhaul Would Be Unprecedented". wkyufm.org. Archived from the original on November 26, 2021. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- ^ Barton, Ryland (June 13, 2019). "Kentucky Supreme Court Rules In Favor Of Bevin's Education Board Overhauls". wkyufm.org. Archived from the original on April 25, 2024. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- ^ "Kentucky Attorney General Andy Beshear files suit against governor, lawmakers on pension reform". WKYT-TV. April 11, 2018. Archived from the original on April 7, 2019. Retrieved May 3, 2019.

- ^ a b Novelly, Thomas (July 9, 2018). "Andy Beshear goes after teacher vote in announcing bid for governor". The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- ^ Novelly, Thomas (December 13, 2018). "Pension ruling hands victory to Andy Beshear over Gov. Matt Bevin". The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved May 3, 2019.

- ^ Lerer, Lisa (December 18, 2018). "Republicans Got Their Health Care Wish. It Backfired". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 26, 2021. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- ^ Henry, Morgan (November 19, 2018). "Beshear files 9th lawsuit on opioid epidemic". WTVQ-DT. Archived from the original on April 6, 2020. Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- ^ "Beshear Secures $17 Million Settlement with Bayer Corporation," Archived November 22, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Kentucky.gov.

- ^ Farrell, Conner (December 6, 2019). "Beshear to appoint AG-elect Cameron to complete rest of term". WHAS-TV. Archived from the original on December 10, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ Pitts, Jacqueline (December 9, 2019). "Daniel Cameron to be sworn in as Kentucky attorney general December 17". The Kentucky Chamber – The Bottom Line. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ Lindstrom, Michon (December 17, 2019). "Daniel Cameron Officially Sworn in As Attorney General". Spectrum News. Archived from the original on December 17, 2019. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- ^ "Daniel Cameron becomes Kentucky's first African American attorney general". WKYT-TV. December 17, 2019. Archived from the original on December 17, 2019. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- ^ Novelly, Thomas (July 9, 2018). "Andy Beshear becomes first to announce run for Kentucky governor". The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- ^ Patrick, Randy (July 9, 2018). "Jacqueline Coleman named Beshear's running mate". The Kentucky Standard. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018.

- ^ Martin, Jonathan (May 21, 2019). "Andy Beshear Wins Democratic Primary for Kentucky Governor". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 2, 2022. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- ^ Bailey, Phillip M. (May 21, 2019). "Andy Beshear Wins the Democratic primary for Kentucky governor". The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- ^ "Andy Beshear wins Democratic nomination for governor". WKYT-TV. May 21, 2019. Archived from the original on May 22, 2019. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- ^ Alan Greenblatt (May 20, 2019). "Why America's Least Popular Governor Will Likely Get Reelected". Governing. Archived from the original on September 30, 2022. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ^ Martin, Jonathan (October 29, 2019). "Kentucky Governor's Race Tests Impact of Impeachment in States". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 2, 2022. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ^ Craven, Julia (November 6, 2019). "Beshear Beats Bevin in Kentucky Governor's Race". Slate. Archived from the original on November 6, 2019. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ a b Coaston, Jane (November 8, 2019). "Matt Bevin's Libertarian opponent says the Kentucky election just proved his point". Vox. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- ^ Watson, Kathryn (November 6, 2019). "Watch live: Democrat Andy Beshear speaks after declaring victory in Kentucky election". CBS News. Archived from the original on January 10, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ "Gubernatorial elections, 2019". Ballotpedia. Retrieved November 11, 2024.

- ^ Bailey, Phillip M.; Tobin, Benjamin; Kobin, Billy; Ladd, Sarah (November 5, 2019). "Kentucky election results 2019: Follow along for live results from Bevin vs Beshear & more". The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

Meanwhile, Kentucky Secretary of State Alison Lundergan Grimes told CNN her office declared Beshear winner of governor race.

- ^ Ratliff, Melissa (November 14, 2019). "Gov. Bevin concedes election following recanvass". WLEX-TV. Archived from the original on November 14, 2019. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- ^ Farrell, Conner (October 1, 2021). "Gov. Beshear files paperwork for 2023 re-election bid". whas11.com. Archived from the original on September 12, 2022. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- ^ Kelly, Erin (May 17, 2023). "Incumbent Gov. Beshear touts record after primary win". Spectrum News 1. Archived from the original on November 4, 2023. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- ^ Zhou, Li (November 7, 2023). "Andy Beshear offers Democrats some lessons for how to win in Trump country". Vox. Archived from the original on November 16, 2023. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ^ Montellaro, Zach (November 7, 2023). "Beshear's win shows Democrats can still win in red states". POLITICO. Archived from the original on November 16, 2023. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ^ Yokley, Eli (July 24, 2023). "U.S. Governor Rankings: Beshear Gets a Boost, DeSantis' Approval Dips". Morning Consult Pro. Archived from the original on November 7, 2023. Retrieved August 1, 2024.

- ^ "Election 2023: Democrats win control of Va. legislature; Ohio residents vote to protect abortion rights". The Washington Post. November 7, 2023. Archived from the original on November 8, 2023. Retrieved July 31, 2024.

- ^ "'Everybody's daughter': The rape victim behind Kentucky's viral abortion ad". Washington Post. December 4, 2023. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Sonka, Joe (November 15, 2019). "Gov.-elect Andy Beshear names transition team members". The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Andy Beshear Swearing In" (video). WLKY. December 10, 2019. Archived from the original on June 15, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2019 – via YouTube.

- ^ Barton, Ryland (February 23, 2021). "Bill To Ban Governors From Overhauling Kentucky Board Of Education Advances". wkyufm.org. Archived from the original on November 26, 2021. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- ^ Derysh, Igor (July 18, 2020). "Gov. Andy Beshear wants to give all Black Kentucky residents health coverage, but there's a catch". Salon. Archived from the original on November 22, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

- ^ a b c Warren Fiske (April 19, 2021). "McAuliffe near the top in restoring ex-felon voting rights". PolitiFact. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Gregorian, Dareh (December 10, 2019). "Kentucky Gov. Beshear to restore voting rights to over 100,000 former felons". NBC News. Archived from the original on October 10, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ Desrochers, Daniel; Brammer, Jack (March 5, 2020). "Senate Republican Leaders go after Andy Beshear's power with three new bills". Lexington Herald-Leader. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021.

- ^ Cook, Katey (April 12, 2020). "KSP records license plates of Maryville Baptist churchgoers from in and out of Ky". WYMT. Archived from the original on November 22, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

- ^ Ladd, Sarah (April 12, 2020). "Police take license numbers, issue notices as Kentucky church holds in-person Easter service". USA Today. The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on May 31, 2021. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ^ Brown, Matthew (April 13, 2020). "Fact check: Did Kentucky order police to record the license plates of Easter churchgoers?". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on November 22, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

- ^ "Governor Promises To Provide Free Health Care For All Black Kentuckians Who Need It". NPR. June 9, 2020. Archived from the original on November 22, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

- ^ Diamond, Dan; Cancryn, Adam (June 9, 2020). "Kentucky governor vows universal coverage for black residents". Politico. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021.

- ^ Coleman, Justine (June 9, 2020). "Kentucky governor outlines plan to provide health coverage for '100 percent' of black communities". The Hill. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021.

- ^ Wheatly, Kevin (November 18, 2020). "Gov. Beshear orders public, private schools to close classrooms starting Monday". WDRB. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c Richard Wolf, Supreme Court denies religious school challenge to Kentucky's expiring COVID-19 restrictions Archived November 29, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, USA Today (December 17, 2020).

- ^ Billy Kobin, Beshear lays out how schools in 'red' counties can resume in-person classes in January Archived January 18, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, Louisville Courier Journal (December 14, 2021).

- ^ "Danville Christian Academy files suit against governor". The Advocate-Messenger. November 23, 2020. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ US appeals court sides with KY governor in closing schools Archived January 4, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Lexington Herald Leader (November 29, 2020).

- ^ Barton, Ryland (March 30, 2021). "Ky. Lawmakers Override Nearly All Of Beshear's Vetoes". 89.3 WFPL News Louisville. Archived from the original on November 24, 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ "Kentucky tornadoes: death toll from record twisters expected to exceed 100". The Guardian. December 12, 2021. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ Lovan, Dylan; Schreiner, Bruce; Brown, Matthew (July 30, 2022). "Governor: Search for Kentucky flood victims could take weeks". AP NEWS. Archived from the original on July 30, 2022. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ Lovan, Dylan; Schreiner, Bruce (July 30, 2022). "Kentucky governor: Death toll from flooding rises to 25". AP NEWS. Archived from the original on July 30, 2022. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ Bailey, Phillip M.; Beggin, Riley; Aulbach, Lucas (January 7, 2024). "Kentucky's Andy Beshear joins other high-profile governors in creating federal PAC". USA Today. Archived from the original on January 8, 2024. Retrieved January 7, 2024.

- ^ a b Karolina Buczek (November 26, 2019). "LEX 18 has one-on-one interview with Gov.-Elect Andy Beshear". WLEX. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Yetter, Deborah (January 31, 2020). "Planned Parenthood gets state OK to provide abortions at Louisville clinic". The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on January 26, 2024. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Holton, Brooks (April 24, 2020). "Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear vetoes abortion legislation". WDRB. Archived from the original on January 31, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Holton, Brooks (April 24, 2020). "Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear vetoes abortion legislation". WDRB. Archived from the original on January 31, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Bailey, Phillip M. (October 11, 2019). "Matt Bevin: Andy Beshear represents 'death over life' in abortion debate". The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Schreiner, Bruce (January 22, 2021). "Kentucky governor allows 'born-alive' bill to become law". ABC News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ Beshear, Andy (March 25, 2020). "State of Emergency" (PDF) (Press release). Commonwealth of Kentucky. 2020-257. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2021.

- ^ "Beshear on Kentucky mask mandate enforcement: 'No shoes, no shirts, no masks, no service'". WLKY. July 14, 2020. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ Barton, Ryland (July 23, 2020). "Republicans Rally Around Opposition To Beshear Coronavirus Response". WFPL. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ Abrams, Floyd; Langford, John (May 19, 2020). "Opinion | The Right of the People to Protest Lockdown". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 27, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ^ Baker, Ken (October 4, 2021). "Beshear's COVID jail and prison commutes lead to increase in crime, report shows". wave3. Archived from the original on January 26, 2024. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ Street, Eileen (November 4, 2020). "Kentucky Lawmakers Could Review Governor's Executive Powers in 2021". Spectrum News 1. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Higgins-Dunn, Noah (November 12, 2020). "Kentucky Supreme Court upholds Gov. Beshear's mask mandate, emergency restrictions". CNBC. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- ^ Otts, Chris (November 18, 2020). "Beshear closes bars, restaurants to indoor service starting Nov. 20". WDRB. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ "Lawmakers criticize Gov. Beshear over new COVID-19 decisions". WLEX. November 20, 2020. Archived from the original on November 24, 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ Martinez, Natalia (November 19, 2020). "COVID contact tracing has not tracked business-specific spread in Kentucky". WAVE. Archived from the original on December 5, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Kobin, Billy (May 14, 2021). "Gov. Andy Beshear: Kentucky to resume 100% capacity, end mask mandate in June". The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2021.

- ^ "Most COVID-19 restrictions lifted Friday across Kentucky". WLEX-TV. June 11, 2021. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2021.

- ^ Sonka, Joe (June 10, 2021). "As Beshear prepares to lift COVID-19 rules, Supreme Court hears cases on governor's powers". The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Alex (June 10, 2021). "Kentucky Justices Weigh Laws Limiting Governor's Covid Powers (1)". Bloomberg Law. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2021.

- ^ "Kentucky's high court reviews case testing executive powers". WOWK-TV. Associated Press. June 10, 2021. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2021.

- ^ Hedrick, Chad (August 10, 2021). "Gov. Beshear mandates masks be worn in all Kentucky schools". WKYT. Archived from the original on August 10, 2021. Retrieved August 11, 2021.

- ^ Walsh, Joe (August 20, 2021). "Judge Rules Against Kentucky's School Mask Mandate". Forbes. Archived from the original on January 26, 2024. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ "Opinion of the Kentucky Supreme Court by Justice VanMeter" (PDF). Kentucky Courts. August 21, 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 21, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ Bruce, Schreiner (August 21, 2021). "Kentucky gov suffers legal defeat in combating COVID surge". Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ Krauth, Olivia (August 23, 2021). "After Kentucky Supreme Court ruling, Gov. Andy Beshear rescinds school mask mandate". Courier Journal. Archived from the original on January 26, 2024. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ Tonya Mosley and Francesca Paris (December 13, 2019). "Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear Restores Voting Rights To Felons". amp.wbur.org. Archived from the original on November 16, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ^ Daniels, CJ (June 20, 2020). "Kentucky governor confirms more than 175K nonviolent offenders have voting rights restored". whas11. Archived from the original on November 16, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ^ Barton, Ryland (March 26, 2021). "Beshear Signs More Bills, Including Juvenile Justice Measure". 89.3 WFPL News Louisville. Archived from the original on November 24, 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ a b "Bill Tracker; KFTC's legislative issues during the 2021 Kentucky General Assembly". Kentuckians For The Commonwealth. Archived from the original on November 24, 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ Duvall, Tessa (October 16, 2023). "Beshear, Cameron debate splitting up JCPS, death penalty and more in Northern Kentucky". Lexington Herald-Leader. Archived from the original on July 27, 2024. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ^ Gracie Lagadinos. "Gov. Beshear: 'We have more in common than what divides us.'". Kentucky Association of Counties. Archived from the original on January 26, 2024. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ "Attorney General Andy Beshears gives his thoughts about Marijuana in Kentucky". wbko. April 8, 2019. Archived from the original on November 19, 2021. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- ^ Brammer, Jack (December 16, 2020). "Beshear tells lawmakers to be 'bold' and pass betting bills, medical marijuana". Lexington Herald-Leader. ISSN 0745-4260. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ Gaskell, Stephanie (November 5, 2019). "Andy Beshear, Governor-Elect of Kentucky: 5 Fast Facts You Need to Know". Heavy. Archived from the original on November 16, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ^ Jaeger, Kyle (November 15, 2022). "Kentucky Governor Signs Executive Orders Allowing Medical Marijuana Possession From Other States And Regulating Delta-8 THC". Marijuana Moment. Archived from the original on November 15, 2022. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ "Historic new laws: Medical marijuana, sports betting now legal in Kentucky". WLKY. March 31, 2023. Archived from the original on March 31, 2023. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ^ Kentucky Archived January 26, 2024, at the Wayback Machine (subscription required)

- ^ Schimmel, Becca (March 13, 2017). "Attorney General Andy Beshear Speaks Out Against Right-To-Work". wkyufm.org. Archived from the original on November 20, 2021. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- ^ Elbert, Alex (April 15, 2020). "Kentucky Legislators Override Vetoed Tax Break for Distilleries". news.bloombergtax.com. Archived from the original on November 24, 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ Coleman, Madeline (June 24, 2021). "Kentucky Becomes First State to Sign an Executive Order for NIL Compensation". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on July 12, 2021. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ Coleman, Madeline (June 24, 2021). "Kentucky Gov. Signs First Executive Order for NIL Compensation". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on July 12, 2021. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ Elahi, Amina (December 10, 2019). "In First Act As Governor, Beshear Remakes Kentucky Board Of Education". wkyufm.org. Archived from the original on November 27, 2021. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- ^ "Dealing with GOP legislature next challenge for Beshear". spectruminfocus.com. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Smith, Kevin Wheatley and Lawrence (November 2021). "Gov. Beshear will 'fight like heck' to raise Kentucky teachers' pay in upcoming session". WDRB. Archived from the original on November 4, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ Jones, Breya (March 17, 2022). "Gov. Beshear calls charter schools unconstitutional ahead of funding proposal". Louisville Public Media. Archived from the original on March 18, 2022. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c "On The Issues". Andy Beshear for Governor. Archived from the original on March 28, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ a b Austin, Emma. "Here's where Kentucky Gov.-elect Andy Beshear stands on abortion, gun laws & other issues". The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on January 26, 2024. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ "Andy Beshear in 2019 KY Governor's race". ontheissues.org. Archived from the original on September 2, 2023. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ "Problem Gambling Awareness Month joins Kentucky Lottery, state council in outreach effort". Northern Kentucky Tribune. May 8, 2020. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Sonka, Joe (March 30, 2023). "Against all odds, sports betting becomes law in Kentucky". Courier Journal. Archived from the original on January 26, 2024. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Czachor, Emily Mae (April 10, 2023). "Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear says friend was killed in Louisville mass shooting". cbsnews.com. Archived from the original on April 13, 2023. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ^ Bradner, Eric (April 12, 2023). "Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear on Louisville bank gunman: 'This person murdered my friend' | CNN Politics". CNN. Archived from the original on April 12, 2023. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ^ "Kentucky governor relaunches kynect with expanded mission". Modern Healthcare. Associated Press. October 5, 2020. Archived from the original on April 30, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2021.

- ^ a b Ragusa, Joe. "Pres. Trump Allowed States, Cities to Opt Out of Resettlement". spectrumnews1.com. Archived from the original on November 27, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ^ Steve Bittenbender (November 9, 2021). "Beshear says infrastructure bill may make Kentucky's Brent Spence bridge project toll-free". The Center Square. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ "Kentucky governor candidates face off in final debate" (video). WLKY. October 29, 2019. Archived from the original on September 2, 2023. Retrieved December 10, 2019 – via YouTube.

- ^ James Pilcher (August 24, 2021). "Kentucky state senator skeptical of Beshear's Brent Spence funding plan". WKRC. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ a b White, Douglas. "Beshear highway plan includes $267 million for I-69". The Gleaner. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ White, Douglas (August 27, 2019). "Beshear says 'we will build I-69 bridge in my first term'". Henderson Gleaner. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ^ Peters, Jeremy W. (November 4, 2019). "A Conservative Push to Make Trans Kids and School Sports the Next Battleground in the Culture War". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 27, 2021. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- ^ Schreiner, Bruce (February 19, 2020). "Governor Makes History by Attending Gay Rights Rally". U.S. News & World Report. Associated Press. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021.

- ^ "Governor bans use of 'conversion therapy' on LGBTQ+ minors in Kentucky". AP News. September 18, 2024.

- ^ Robertson, Campbell; Londoño, Ernesto (March 29, 2023). "G.O.P. Lawmakers Override Kentucky Governor's Veto on Anti-Trans Law". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 30, 2023. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ^ Schreiner, Bruce (February 27, 2020). "Kentucky governor defends photo posing with drag queens". Associated Press News. Retrieved July 31, 2024.

- ^ Cheves, John (March 23, 202). "Taking $1.13 billion from teacher pensions a 'very serious problem,' official warns". Lexington Herald-Leader. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ "Andy Beshear (D)". National Association of Attorneys General. Archived from the original on November 6, 2019. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ Dwilson, Stephanie Dube (November 6, 2019). "Britainy Beshear, Andy Beshear's Wife: 5 Fast Facts You Need to Know". Heavy. Archived from the original on November 6, 2019. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ Beshear, Andy; Edwards, John Bel (November 25, 2019). "Opinion | How Democrats can win, everywhere". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on November 16, 2023. Retrieved August 1, 2024.

- ^ Beshear, Andy (November 12, 2024). "I'm the Governor of Kentucky. Here's How Democrats Can Win Again". New York Times.

- ^ "Official Election Results". Kentucky State Board of Elections. Archived from the original on May 21, 2015. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- ^ "Election Candidate Filings – Governor". web.sos.ky.gov. Archived from the original on January 30, 2023. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

- ^ Tanneeru, Manav. "2023 Elections | CNN Politics". CNN. Archived from the original on November 8, 2023. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- ^ "Kentucky Governor Live Election Results 2023: Gov. Andy Beshear wins". nbcnews.com. Archived from the original on November 14, 2023. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

External links

[edit]- Governor Andy Beshear government website

- Andy Beshear for Kentucky campaign website

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 1977 births

- 21st-century Kentucky politicians

- Democratic Party governors of Kentucky

- Kentucky attorneys general

- Kentucky lawyers

- Living people

- Politicians from Louisville, Kentucky

- University of Virginia School of Law alumni

- Vanderbilt University alumni

- American Disciples of Christ

- Beshear family

- 21st-century American lawyers