History of Bengal

| History of Bengal |

|---|

|

| History of South Asia |

|---|

|

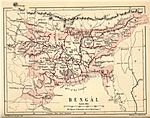

The history of Bengal is intertwined with the history of the broader Indian subcontinent and the surrounding regions of South Asia and Southeast Asia. It includes modern-day Bangladesh and the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura and Assam's Karimganj district, located in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent, at the apex of the Bay of Bengal and dominated by the fertile Ganges delta. The region was known to the ancient Greeks and Romans as Gangaridai, a powerful kingdom whose war elephant forces led the withdrawal of Alexander the Great from India. Some historians have identified Gangaridai with other parts of India. The Ganges and the Brahmaputra rivers act as a geographic marker of the region, but also connects the region to the broader Indian subcontinent.[1] Bengal, at times, has played an important role in the history of the Indian subcontinent.

The area's early history featured a succession of Indian empires, internal squabbling, and a tussle between Hinduism and Buddhism for dominance. Ancient Bengal was the site of several major Janapadas (kingdoms), while the earliest cities date back to the Vedic period. A thalassocracy and an entrepôt of the historic Silk Road,[1] ancient Bengal had strong trade links with Persia, Arabia and the Mediterranean that focused on its lucrative cotton muslin textiles.[2] The region was a part of several ancient pan-Indian empires, including the Mauryans and Guptas. It was also a bastion of regional kingdoms. The citadel of Gauda served as capital of the Gauda Kingdom, the Buddhist Pala Empire (eighth to 11th century), the Hindu Sena Empire (11th–12th century) and the Hindu Deva Empire (12th-13th century). This era saw the development of Bengali language, script, literature, music, art and architecture.

The Muslim conquest of the Indian subcontinent absorbed Bengal into the medieval Islamic and Persianate worlds.[3] Between the 1204 and 1352, Bengal was a province of the Delhi Sultanate.[4] This era saw the introduction of the taka as monetary currency, which has endured into the modern era. An independent Bengal Sultanate was formed in 1346 and ruled the region for two centuries, during which Islam was the state religion.[5][6] The ruling elite also turned Bengal into the easternmost haven of Indo-Persian culture.[3] The Sultans exerted influence in the Arakan region of Southeast Asia, where Buddhist kings copied the sultanate's governance, currency and fashion. A relationship with Ming China flourished under the sultanate.[7]

The Bengal Sultanate was notable for its Hindu aristocracy, including the rise of Raja Ganesha and his son Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah as usurpers. Hindus served in the royal administration as prime ministers and poets. Under the patronage of Sultans like Alauddin Hussain Shah, Bengali literature began replacing the strong influence of Sanskrit in the region. Hindu principalities included the Kingdom of Mallabhum, Kingdom of Bhurshut and Kingdom of Tripura; and the realm of powerful Hindu Rajas such as Pratapaditya, Kedar Ray and Raja Sitaram Ray.[8]

Following the decline of the sultanate, Bengal came under the suzerainty of the Mughal Empire, as its wealthiest province. Under the Mughals, Bengal Subah rose to global prominence in industries such as textile manufacturing and shipbuilding,[9] its economy in the 18th century exceeding in size any of Europe's empires.[10] This growth of manufacturing has been seen as a form of proto-industrialization, similar to that in western Europe prior to the Industrial Revolution.[citation needed] Bengal's capital Dhaka is said to contained over a million people.[11]

The gradual decline of the Mughal Empire led to quasi-independent states under the Nawabs of Bengal, subsequent to the Maratha invasions of Bengal, and finally the conquest by the British East India Company.

The East India Company took control of the region from the late 18th century. The company consolidated their hold on the region following the battles of Battle of Plassey in 1757 and Battle of Buxar in 1764 and by 1793 took complete control of the region. Capital amassed from Bengal by the East India Company was invested in various industries such as textile manufacturing in Great Britain during the initial stages of the Industrial Revolution.[12][13][14][15] Company policies in Bengal also led to the deindustrialization of the Bengali textile industry during Company rule.[12][14] Kolkata (or Calcutta) served for many years as the capital of British controlled territories in India. The early and prolonged exposure to the British colonial administration resulted in the expansion of Western-style education, culminating in development of science, institutional education, and social reforms in the region, including what became known as the Bengali Renaissance. A hotbed of the Indian independence movement through the early 20th century, Bengal was partitioned during India's independence in 1947 along religious lines into two separate entities: West Bengal—a state of India—and East Bengal—a part of the newly created Dominion of Pakistan that later became the independent nation of Bangladesh in 1971.

Etymology

[edit]The exact origin of the word Bangla is unknown, though it is believed to be derived from the Dravidian-speaking tribe Bang/Banga that settled in the area around the year 1000 BCE.[16][17] Other accounts speculate that the name is derived from Venga (Bôngo), which came from the Austroasiatic word "Bonga" meaning the Sun-god. According to the Mahabharata, the Puranas and the Harivamsha, Vanga was one of the adopted sons of King Vali who founded the Vanga Kingdom. It was either under Magadh or under Kalinga Rules except few years under Pals. The earliest reference to "Vangala" (Bangala) has been traced in the Nesari plates (805 CE) of Rashtrakuta Govinda III which speak of Dharmapala as the king of "Vangala". The records of Rajendra Chola I of the Chola dynasty, who invaded Bengal in the 11th century, use the term Vangaladesa.[18][19][20]

The term Bangalah is one of the precursors to the modern terms Bengal and Bangla.[21][22][23] Bangalah was the most widely used term for Bengal during the medieval and early modern periods. The Sultan of Bengal was styled as the Shah of Bangalah. The Mughal province of Bengal was termed Subah-i-Bangalah. An interesting theory of the origin of the name is provided by Abu'l-Fazl in his Ain-i-Akbari. According to him, "[T]he original name of Bengal was Bung, and the suffix "al" came to be added to it from the fact that the ancient rajahs of this land raised mounds of earth 10 feet high and 20 in breadth in lowlands at the foot of the hills which were called "al". From this suffix added to the Bung, the name Bengal arose and gained currency".[24]

Prehistory

[edit]

Stone Age tools found in the region indicate human habitation for over 20,000 years.[25] Remnants of Copper Age settlements, including pit dwellings, date back 4,000 years.[25] Bengal was settled by Indo-Aryans, Tibeto-Burmans, Dravidians and Austroasiatics in consecutive waves of migration.[16][25] Archaeological evidence confirms that by the second millennium BCE, the Bengal delta was inhabited by rice-cultivating communities, with people living in systemically-aligned housing and producing pottery.[26] Rivers such as the Ganges and Brahmaputra were used for transport while maritime trade flourished in the Bay of Bengal.[26]

Iron Age

[edit]The Iron Age saw the development of coinage, metal weapons, agriculture and irrigation.[26] Large urban settlements formed in the middle of the first millennium BCE,[27] when the Northern Black Polished Ware culture dominated the northern part of Indian subcontinent.[28] Alexander Cunningham, the founder of the Archaeological Survey of India, identified the archaeological site of Mahasthangarh as the capital of the Pundra Kingdom mentioned in the Rigveda.[29][30]

Early literary and geographic accounts

[edit]The ancient Bengal region features prominently in legendary history of India, Sri Lanka, Siam, Indonesia, Cambodia, Burma, Nepal, Tibet, China and Malaya. According to the Indian epic Mahabharata, the Vanga Kingdom was located in Bengal. Vanga was described as a thalassocracy with colonies in Southeast Asia. According to Sri Lankan history, the first king of Sri Lanka was Prince Vijaya who led a fleet from India to conquer the island of Lanka. Prince Vijaya's ancestral home was Bengal.[31]

In the Greco-Roman world, accounts of the Gangaridai Kingdom are considered by historians to have referred to Bengal. At the time of Alexander the Great's invasion of India, the collective might of the Gangaridai/Nanda Empire deterred the Greek army. The Gangaridai army was stated to have a war elephant cavalry of 6000 elephants.[32] The archaeological sites of Wari-Bateshwar and Chandraketugarh are linked to the Gangaridai kingdom. In Ptolemy's world map, the emporium of Sounagoura (Sonargaon) was located in Bengal.[33] Roman geographers also noted the existence of a large natural harbour in southeastern Bengal, corresponding to the present-day Chittagong region.[34]

Bengal in Vedic period

[edit]Ancient Bengal was often divided between various kingdoms in Vedic Period. At times, the region was unified into a single realm; while it was also ruled by pan-Indian empires.

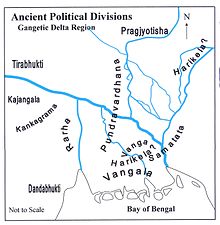

Ancient geopolitical divisions

[edit]

The following table lists the geopolitical divisions of ancient Bengal. The table includes a list of corresponding modern regions, which formed the core areas of the geopolitical units. The territories of the geopolitical divisions expanded and receded through the centuries.

| Ancient region | Modern region |

|---|---|

| Pundravardhana | Rajshahi Division and Rangpur Division in Bangladesh; Malda division of West Bengal in India |

| Vanga | Dhaka Division and Barisal Division in Bangladesh |

| Tirabhukti | Mithila area of India and Nepal |

| Suhma | Burdwan division, Medinipur division and Presidency division of West Bengal in India |

| Radha | Location unclear; probable location in southern West Bengal and parts of Jharkhand of India |

| Samatata | Dhaka Division, Barisal Division and Chittagong Division in Bangladesh |

| Harikela | Sylhet Division, Chittagong Division, Dhaka Division and Barisal Division in Bangladesh |

| Pragjyotisha | Karimganj district of Barak Valley region of Assam in India; Sylhet Division and Dhaka Division in Bangladesh |

Bengal under Magadha empires

[edit]

Nanda Empire (c. 345 – 322 BCE)

[edit]The Nanda empire under Mahapadma Nanda extended to its peak. Mahapadma Nanda started imperial conquest of Bharatvarsh. He invaded and defeated local kingdoms of Bengal.[35] The Nanda empire appears to have stretched from present-day Punjab in the west to Odisha and Bengal in the east.[36] According to the Jain tradition, the Nanda minister subjugated the entire country up to the coastal areas.[37]

Mauryan Empire (c. 322 – 185 BCE)

[edit]The Mauryan Empire unified most of the Indian subcontinent into one state for the first time and was one of the largest empires in subcontinental history.[38] The empire was established by Chandragupta Maurya. Under Mauryan rule, the economic system benefited from the creation of a single efficient system of finance, administration, and security. The reign of Ashoka ushered an era of social harmony, religious transformation, and expansion of the sciences and of knowledge. Ashoka sponsored the spreading of Buddhist missionaries to various parts of Asia.[39] The Mauryans built the Grand Trunk Road, one of Asia's oldest and longest major roads connecting the Indian subcontinent with Central Asia.[40] A passage from Pliny suggests that the "Palibothri" or the rulers of Pataliputra, held dominion over the entire region along the Ganges River. Chinese traveler Hiuen Tsang observed stupas attributed to Ashoka in various locations, including Tamralipti and Karnasuvarna in West Bengal, Samataṭa in East Bengal, and Pundravardhana in North Bengal (currently in Bangladesh), indicating the widespread influence of the Magadhan Empire during Ashoka's reign.[41] During Ashoka's time, Tamralipta served as the principal port of the Magadhan Empire, facilitating communication between Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka) and Magadha. Ashoka is known to have visited Bengal, and he likely traveled to Tamralipta on at least one occasion. According to the Ceylonese chronicle, the Mahavamsa, Ashoka visited Tamralipta when Mahendra and Sanghamitta embarked on their voyage to Sinhala, carrying a holy branch of the Bodhi tree. This event occurred during the reign of the pious King Devanampriya Tissa of Ceylon.[42]

The Mahasthangarh inscription is an important piece of evidence that supports the presence of Mauryan rule in Bengal. Mahasthangarh, located in present-day Bogra District in Bangladesh, was an ancient city known as Pundranagara. The site holds great historical significance as one of the earliest urban centers in Bengal. The inscription, discovered at Mahasthangarh, is written in Brahmi script, which was widely used during the Mauryan period.[44] The Mauryans, who were ruling the Magadhan empire and had their capital in Pāțaliputra, created two major bases in the east-Mahasthan and Bangarh.[45]

Shunga Empire and Kanva dynasty (c. 185 – 28 BCE)

[edit]Ancient Bengal was often ruled by dynasties based in the Magadha region, such as the Shunga dynasty and Kanva dynasty.

Classical Bengal

[edit]Gupta Empire

[edit]

The Gupta Empire is regarded as a golden age in subcontinental history. It was marked by extensive scientific and cultural advancements that crystallised the elements of what is generally known as Hindu culture.[46] The Hindu numeral system, a positional numeral system, originated during Gupta rule and was later transmitted to the West through the Arabs. Early Hindu numerals had only nine symbols, until 600 to 800 CE, when a symbol for zero was developed for the numeral system.[47] The peace and prosperity created under leadership of Guptas enabled the pursuit of scientific and artistic endeavours in the empire.[48]

Bengal was an important province of the Gupta Empire. The discovery of Gupta era coins across Bengal point to a monetised economy.[49]

Gauda kingdom

[edit]King Shashanka is considered by some scholars to be the pioneering king of a unified Bengali state. Shashanka established a kingdom in the citadel of Gauda. His reign lasted between 590 and 625. The Bengali calendar traces its origin to Shashanka's reign.

Varman dynasty

[edit]The Varman dynasty of Kamarupa ruled parts of North Bengal and the Sylhet region. The area was a melting pot of the Bengali-Assamese languages.

Khadga dynasty

[edit]The Khadga dynasty was a Buddhist dynasty of eastern Bengal. One of the legacies of the dynasty is its gold coinage inscribed with the names of rulers such as Rajabhata.

Pala Empire

[edit]

The Pala Empire (750–1120 CE) was a Bengali empire and the last Buddhist imperial power on the Indian subcontinent. The Palas were followers of the Mahayana and Vajrayana schools of Buddhism. Gopala I (750–770) was its first ruler. He came to power in 750 through an election by chieftains in Gauḍa. Gopala reigned from about 750–770 and consolidated his position by extending his control over all of Bengal.

The Pala dynasty lasted for four centuries and ushered in a period of stability and prosperity in Bengal. They created many temples and works of art as well as supported the important ancient higher-learning institutions of Nalanda and Vikramashila. The Somapura Mahavihara built by Emperor Dharmapala is the greatest Buddhist monastery in the Indian subcontinent.

The empire reached its peak under Emperor Dharmapala (770–810) and Devapala (810–850). Dharmapala extended the empire into the northern parts of the Indian subcontinent. According to Pala copperplate inscriptions, his successor Devapala exterminated the Utkalas, invade the Kamarupa Kingdom of Assam, shattered the pride of the Huna people and humbled the lords of Gurjara-Pratihara and the Rashtrakuta dynasty.

Chandra dynasty

[edit]

The Chandra dynasty ruled southeastern Bengal and Arakan between the 10t CE.[50] The dynasty was powerful enough to withstand the Pala Empire to the northwest. The Chandra kingdom covered the Harikela region, which was known as the Kingdom of Ruhmi to Arab traders.[51] The dynasty's realm was a bridge between India and Southeast Asia. During this period, the port of Chittagong developed banking and shipping industries.[52] The last ruler of the Chandra Dynasty, Govindachandra, was defeated by the south Indian Emperor Rajendra Chola I of the maritime Chola dynasty in the 11th century.[53]

Sena Empire

[edit]

The Pala dynasty was replaced by the resurgent Hindu Sena dynasty which hailed from south India; they and their feudatories are referred to in history books as the "Kannada kings". In contrast to the Pala dynasty who championed Buddhism, the Sena dynasty were staunchly Hindu. They brought about a revival of Hinduism and cultivated Sanskrit literature in eastern India. They succeeded in bringing Bengal under one ruler during the 12th century. Vijaya Sena, second ruler of the dynasty, defeated the last Pala emperor, Madanapala, and established his reign formally. Ballala Sena, third ruler of the dynasty, was a scholar and philosopher king. He is said to have invited Brahmins from both south India and north India to settle in Bengal, and aid the resurgence of Hinduism in his kingdom. He married a Western Chalukya princess and concentrated on building his empire eastwards, establishing his rule over nearly all of Bengal and large areas of lower Assam. Ballala Sena made Nabadwip his capital.[54]

The fourth Sena king, Lakshmana Sena, son of Ballala Sena, was the greatest king of his line. He expanded the empire beyond Bengal into Bihar, Assam, Odisha and likely Varanasi. Lakshmana was later defeated by the nomadic Turkic Muslims and fled to eastern Bengal, where he ruled few more years. It is proposed by some Bengali authors that Jayadeva, the famous Sanskrit poet and author of Gita Govinda, was one of the Pancharatnas or "five Gems" of the court of Lakshmana Sena.

Deva dynasty

[edit]The Deva dynasty was a Hindu dynasty of medieval Bengal that ruled over eastern Bengal after the collapse of Sena Empire. The capital of this dynasty was Bikrampur in present-day Munshiganj District of Bangladesh. The inscriptional evidences show that his kingdom was extended up to the present-day Comilla–Noakhali–Chittagong region. A later ruler of the dynasty Ariraja-Danuja-Madhava Dasharatha-Deva extended his kingdom to cover much of East Bengal.[55] The Deva dynasty endured after Muslim conquests but eventually died out.

Islamic Era

[edit]Ghurids

[edit]The Ghurid invasion of Bengal in 1202 was a military campaign of the Ghurid dynasty led by Muhammad Bhakhtiyar Khalji against the Sena dynasty. Bakhtiyar Khalji emerged victorious in the campaign and subsequently annexed Nabadwip, a significant portion of the territory controlled by the Sena Dynasty. Following their defeat, Lakshmana Sena, the ruler of the Sena dynasty, retreated to the southeastern region of Bengal.

Khalijis of Bengal

[edit]The Khalji dynasty was a Turko-Afghan dynasty which was the first independent Muslim Bengali State it lasted between 1204–1231 and was eventually annexed by the Delhi Sultanate.

Delhi Sultanate (1204–1352)

[edit]The Islamic conquest of Bengal began with the capture of Gauda from the Sena dynasty in 1204. Led by Bakhtiar Khilji, an army of several thousand horsemen from the Ghurids overwhelmed Bengali Hindu forces during a blitzkrieg campaign. After victory, the Delhi Sultanate maintained a strong vigil on Bengal. Coins were inscribed in gold with the Sanskrit inscription Gaudiya Vijaye, meaning "On the conquest of Gauda (Bengal)". Several governors of Delhi in Bengal attempted to break away and create an independent state. But the Delhi Sultanate managed to suppress Bengal's Muslim separatists for a century.[56] Gradually, eastern Bengal was absorbed into Muslim rule by the 14th century, such as through the Conquest of Sylhet. Sufis played a role in the Islamic absorption of Bengal. During the Tughluq dynasty, the taka was introduced as the imperial currency.[57]

Small sultanates (1338–1352)

[edit]

During the middle of the 14th century, three break away sultanates emerged in the Delhi Sultanate's province of Bengal. These included a realm led by Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah (and later his son) in Sonargaon;[58] a realm led by Alauddin Ali Shah in Gauda (also called Lakhnauti);[59] and a realm led by Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah in Satgaon. The Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta visited Sonargaon during the reign of Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah. Ibn Battua also visited the Sufi leader Shah Jalal in Sylhet, who had earlier defeated the Hindu ruler Govinda.[60][61]

Bengal Sultanate (1352–1576)

[edit]- Adina Mosque

-

The Adina Mosque was India's largest mosque.

-

Ruins of the prayer hall

-

The Sultan's upper floor gallery

-

Central mihrab

-

Exterior design

Ilyas Shahi dynasty (1342–1414 and 1435–1487)

[edit]In 1352, Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah unified the three small sultanates in Bengal into a single government. Ilyas Shah proclaimed himself as the "Shah of Bangalah". His son Sikandar Shah defeated the Sultan of Delhi and secured recognition of Bengal's sovereignty after the Bengal Sultanate-Delhi Sultanate War. The largest mosque in India was built in Bengal to project the new sultanate's imperial ambitions. The sultans advanced civic institutions and became more responsive and "native" in their outlook. Considerable architectural projects were undertaken which induced the influence of Persian architecture, Arab architecture and Byzantine architecture in Bengal. The dynasty was a promoter of Indo-Persian culture. One of the sultans, Ghiyasuddin Azam Shah, kept a correspondence with the renowned Persian poet Hafez.

The early Bengal Sultanate was notable for its diplomatic relationships. Embassies were sent to Ming China during the reign of Emperor Yongle. China responded by sending envoys, including the Treasure voyages; and mediating in regional disputes. There are also records of the sultans' relations with Egypt, Herat and some kingdoms in Africa.

The Ilyas Shahi Dynasty was interrupted in 1414 by a native uprising but was restored by Nasiruddin Mahmud Shah in 1433.

Hindu-Muslim usurpers (1414–1435)

[edit]The Ilyas Shahi reign was interrupted by an uprising orchestrated by the sultan's premier Raja Ganesha, a Hindu aristocrat. Ganesha installed his son Jadu to the throne but his son was influenced to convert to Islam [citation needed] by the court's Sufi clergy. Jadu took the title of Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah. His reign saw native Bengali elements promoted in the court's culture. Bengali influences were incorporated into the kingdom's architecture. The Bengal Sultanate-Jaunpur Sultanate War ended after mediation from China and the Timurids. Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah also pursued the Reconquest of Arakan to reinstall Arakan's king to the throne after he had been deposed by Burmese forces.[citation needed]

Hussain Shahi dynasty (1494–1538)

[edit]

The Bengal Sultanate's territory reached its greatest extent under Alauddin Hussain Shah, founder of the Hussain Shahi dynasty. The dynasty is regarded by several historians as a golden age in which a syncretic Bengali culture evolved including elements of Muslim and Hindu traditions. For example, the Muslim sultan promoted the translation of Sanskrit epics like the Ramayana into the Bengali language. The promotion of Bengali literature under the dynasty led to Bengali replacing the strong influence of Sanskrit in the region.

Suri interruption (1539–1564)

[edit]In the 16th century, the Mughal emperor Humayun was forced to take shelter in Persia as the conqueror Sher Shah Suri rampaged through the subcontinent. Bengal was brought the control of the short-lived Suri Empire.

Karrani dynasty (1564–1576)

[edit]An Afghan dynasty was the last royal house of the Bengal Sultanate. The capital of the dynasty was Sonargaon. The dynasty also ruled parts of Bihar and Orissa. Its eastern boundary was formed by the Brahmaputra River.

Mughal Period

[edit]The Mughal absorption of Bengal began with the Battle of Ghaghra in 1529, in which the Mughal army was led by the first Mughal emperor Babur. The second Mughal emperor Humayun occupied the Bengali capital Gaur for six months.[62] The Battle of Tukaroi oversaw a similar fate for the Bengal Sultanate with Mughal victory and parts of Bengal was annexed by the Mughals and some other parts were annexed by the Koch Dynasty.[63] Following the collapse of the Bengal Sultanate in the Battle of Raj Mahal in 1576, the Bengal region was brought under Mughal control as the Bengal Subah.

Baro-Bhuyans (1576–1610)

[edit]A confederation of twelve zamindar families resisted the expansion of the Mughal Empire during the 16th and 17th centuries. The zamindars included Muslims and Hindus. They were led by Isa Khan of Bengal. Many prominent figures like the Bengali Hindu jessore king Pratapaditya rose up and carved their own kingdoms within the Bhati. The Baro-Bhuyans defeated the Mughal navy during several engagements in Bengal's rivers. Eventually, the Mughals subdued the zamindar rebellion and brought all of Bengal under imperial control.

Subedar period (1574–1727)

[edit]Subedars were the Mughal viceroys in Bengal. The Bengal Subah was part of a larger prosperous empire and shaped by imperial policies of pluralistic government. The Mughals built the provincial capital in Dhaka in 1610 with fortifications, gardens, tombs, palaces and mosques. Dhaka was also named in honour of Emperor Jahangir as Jahangirnagar. Shaista Khan's conquest of Chittagong in 1666 defeated the (Burmese) Kingdom of Arakan and reestablished Bengali control of the port city. The Chittagong Hill Tracts frontier region was made a tributary state of Mughal Bengal and a treaty was signed with the Chakma Circle in 1713.

Members of the imperial family were often appointed to the position of Subedar. Raja Man Singh I, the Rajput ruler of Kingdom of Amber was the only Hindu subedar. One subedar was Prince Shah Shuja, who was the son of Emperor Shah Jahan. During the struggle for succession with his brothers Prince Aurangazeb, Prince Dara Shikoh and Prince Murad Baksh, Prince Shuja proclaimed himself as the Mughal Emperor in Bengal. He was eventually defeated by the army of Aurangazeb.

Bengal in the Mughal economy

[edit]

Under the Mughal Empire, Bengal was an affluent province with a Muslim majority and Hindu minority. According to economic historian Indrajit Ray, it was globally prominent in industries such as textile manufacturing and shipbuilding.[9] The capital Dhaka had a population exceeding a million people, and with an estimated 80,000 skilled textile weavers. It was an exporter of silk and cotton textiles, steel, saltpetre, and agricultural and industrial produce.[11]

Bengali farmers and agriculturalists were quick to adapt to profitable new crops between 1600 and 1650. Bengali agriculturalists rapidly learned techniques of mulberry cultivation and sericulture, establishing Bengal as a major silk-producing region of the world.[64]

Under Mughal rule, Bengal was a center of the worldwide muslin and silk trades. During the Mughal era, the most important center of cotton production was Bengal, particularly around its capital city of Dhaka, leading to muslin being called "daka" in distant markets such as Central Asia.[65] Domestically, much of India depended on Bengali products such as rice, silks and cotton textiles. Overseas, Europeans depended on Bengali products such as cotton textiles, silks and opium; Bengal accounted for 40% of Dutch imports from Asia, for example, including more than 50% of textiles and around 80% of silks.[66] From Bengal, saltpetre was also shipped to Europe, opium was sold in Indonesia, raw silk was exported to Japan and the Netherlands, and cotton and silk textiles were exported to Europe, Indonesia and Japan.[67]

Bengal had a large shipbuilding industry. Indrajit Ray estimates shipbuilding output of Bengal during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries at 223,250 tons annually, compared with 23,061 tons produced in thirteen colonies in North America from 1769 to 1771.[68]

Nawabs of Bengal (1717–1772)

[edit]By the 18th century, Mughal Bengal became a de-facto independent country under the nominal rule of the Nawabs of Bengal. The subedar was elevated to the status of a hereditary Nawab Nazim. The Nawabs maintained de facto control of Bengal while minting coins in the name of the emperor in Delhi.

Nasiri dynasty (1717–1740)

[edit]The dynasty was founded by the first Nawab of Bengal Murshid Quli Khan. Its other rulers included Sarfaraz Khan and Shuja-ud-Din Muhammad Khan.

Afsar dynasty (1740–1757)

[edit]The dynasty was founded by Alivardi Khan. His grandson and successor Siraj-ud-daulah was the last independent Nawab of Bengal due to his defeat to British forces at the Battle of Plassey in 1757. Najafi dynasty Nawabs continued to rule as semi-independent till 1772 after which British East India Company took complete control of this former Mughal province.

Nawab Alivardi Khan took the throne after a bloody Battle at Giria, killing Sarfaraz Khan and usurping power.

Maratha Invasions

[edit]The resurgent Maratha Confederacy emerging from Maharashtra quickly repulsed the Mughals and subjugated them to the confines of Delhi. It was during this period they were at the doorsteps of the independent Bengal Subah, particularly Orissa. They conducted raids within Bengal and plundered cities and villages and caused widespread devastation.[69][70] The Marathas initially succeeded against the Bengali forces at the Battle of Jaipur however, throughout all of their attempts the Marathas were never able to succeed in occupying Orissa or any part of Bengal without being kicked out by Nawab Alivardi Khan shortly after.[citation needed]

The raids lasted almost yearly between 1742 and 1751. Nawab Alivardi Khan fought the Maratha forces many times for the safeguarding of Orissa. The Bengali forces and Bargis (Marathas) fought face to face on many occasions such as the First Battle of Katwa, Second Battle of Katwa, Battle of Birbhum, First Battle of Midnapur, Second Battle of Midnapur and the Battle of Burdwanwhere Alivardi Khan repelled all their attacks.[71]

During their raids, the Marathas killed close to 400,000 people in western Bengal and Bihar. This devastated Bengal's economy, as many of the people killed in the Maratha raids included merchants, textile weavers, silk winders, and mulberry cultivators.[72][73] The Cossimbazar factory reported in 1742, for example, that the Marathas burnt down many of the houses along with weavers' looms.[73] The plundering has been considered to be among the deadliest massacres in Indian history.[74]

However due to their relentless attacks and raids the Nawab would be more partial towards signing the treaty eventually agreeing to cede Orissa to the Maratha Confederacy to ensure peace for both states.[71]

Hindu states

[edit]- Kantajew Temple

-

Front of the temple

-

Terracotta river scene

-

Terracotta Kalki

-

Temple pillar

There were several Hindu states established in and around Bengal during the medieval and early modern periods. These kingdoms contributed a lot to the economic and cultural landscape of Bengal. Extensive land reclamation in forested and marshy areas were carried out and intrastate trade as well as commerce were highly encouraged. These kingdoms also helped introduce new music, painting, dancing and sculpture into Bengali art-forms as well as many temples were constructed during this period. Militarily, they served as bulwarks against Portuguese and Burmese attacks. These states includes the principalities of Maharaja Pratap Aditya of Jessore, Raja Sitaram Ray of Burdwan, Raja Krishnachandra Roy of Nadia Raj and Kingdom of Mallabhum. The Kingdom of Bhurshut was a medieval Hindu kingdom spread across what is now Howrah and Hooghly in the Indian state of West Bengal. Maharaja Rudranarayan consolidated the dynasty and expanded the kingdom and converted it into one of the most powerful Hindu kingdom of the time. His wife Maharani Bhavashankari defeated the Pathan resurgence in Bengal[75] and her reign brought power, prosperity and grandeur to Bhurishrestha Kingdom. Their son, Maharaja Pratapnarayan, patronised literature and art, trade & commerce, as well as welfare of his subjects. Afterwards, Maharaja Naranarayan maintained the integrity and sovereignty of the kingdom by diplomatically averting the occupation of the kingdom by the Mughal forces. His son, Maharaja Lakshminarayan, failed to maintain the sovereignty of the kingdom due to sabotage from within. The Koch Bihar Kingdom in the northern Bengal, flourished during the period of 16th and the 17th centuries as well as weathered the Mughals and survived till the advent of the British.[76] The Burdwan Raj founded by Maharaja Sangam Rai Kapoor was a zamindari estate that flourished from about 1657 to 1955, first under the Mughals and then under the British in the province of Bengal in British-India. At the peak of its prosperity in the 18th century, the estate extended to around 5,000 square miles (13,000 km2) of territory[77] and even up to the early 20th century paid an annual revenue to the government in excess of 3,300,000 rupees.

Immigration

[edit]Bengal received many immigrants from West Asia, Central Asia, the Horn of Africa and North India during the sultanate and Mughal periods. Many came as refugees due to the Mongol invasions and conquests. Others found Bengal's fertile land suitable for economic production and commerce. The Arabs were among the earliest settlers, especially in coastal areas.[78] Persians settled in Bengal to become clerics, missionaries, lawyers, teachers, soldiers, administrators and poets.[79] An Armenian community from the Safavid Empire migrated to the region.[80] There were also many Turkic immigrants.[81] The Portuguese were the earliest Europeans to settle in Bengal.[82]

Many Arakanese escaped persecution in Burma and settled in southern Bengal during the 18th century.[83] Many Manipuris settled in eastern Bengal during the 18th century after fleeing from conflict-ridden areas in Assam.[84] The Marwari community continues to be influential in West Bengal's economic sectors. The Marwaris migrated from Rajasthan in western India. In Bangladesh, a Nizari Ismaili community with diverse origins continues to play a significant role in economic sectors.

European Settlements in Bengal

[edit]

Portuguese Chittagong (1528–1666)

[edit]The first European colonial settlement in Bengal was the Portuguese settlement in Chittagong. The settlement was established after the Bengal Sultanate granted permission to embassies from Portuguese India for the creation of a trading post. The Portuguese settlers in Chittagong included bureaucrats, merchants, soldiers, sailors, missionaries, slave traders and pirates. They controlled the port of Chittagong and forced all merchant ships to acquire a Portuguese trade licence. The Roman Catholic Church was established in Bengal by the Portuguese in Chittagong, when the first Vicar Apostolic was appointed in the port city.

The Portuguese eventually came under the protection of the Kingdom of Mrauk U as the Bengal Sultanate lost control of the Chittagong region. In 1666, the Mughal conquest of Chittagong resulted in the expulsion of Portuguese and Arakanese forces in the port city. The Portuguese also migrated to other parts of Bengal, including Bandel and Dhaka.

The Portuguese brought with them exotic fruits, flowers and plants, which quickly became part of Bengali life: potato, cashew nut, chilli, papaya, pineapple, Carambola (Averrhoa carambola), guava, Alphonso mango (named after Afonso de Albuquerque) and tomatoe, among others, showing their zeal for agri-horticulture. Even the Krishna Kali flower (Mirabilis jalapa) plant, with its varied colours, was a gift of the Portuguese. From their arrival, the Portuguese married local women, as a result, many Portuguese words like janala, almari, verandah, chabi, balti, perek, alpin, toalia came into the Bengali vocabulary. They also developed a great interest in the Bengali language. The first printed book in prose in Bengali was by a Portuguese, as was the first Bengali grammar and dictionary: Manuel da Assumpção took on this monumental task, it was the first step to standardising and printing in the Bangla language, which slowly helped break the hegemony of the Persian language.[85] Till today most Bangladeshi Christians have Portuguese surnames.[86]

Dutch settlements (1610–1824)

[edit]

The Dutch East India Company operated a directorate in Bengal for nearly two centuries. The directorate later became a colony of the Dutch Empire in 1725. Dutch territories in Bengal were ceded to Britain by the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824. Dutch settlements in Bengal included the Dutch settlement in Rajshahi, the main Dutch port in Baliapal, as well as factories in Chhapra (saltpetre), Dhaka (muslin), Balasore, Patna, Cossimbazar, Malda, Mirzapur, Murshidabad, Rajmahal and Sherpur.

Bengal once accounted for 40% of Dutch imports from Asia, particularly in terms of silk and muslin goods.[87]

Early English settlements (1600s)

[edit]The East India Company established its first settlements in Bengal around Hooghly during the 1630s.[88] It received an official permission to trade from Mughal viceroy Shah Shuja in 1651.[88] In 1689, the company attempted to take Chittagong and make it the headquarters of their Bengal trade but the English expedition found the port heavily defended.[89][90] In 1696, the English built Fort William on the bank of the Hooghly River. Fort William served as the British headquarters in India for centuries. The area around Fort William eventually grew into the city of Calcutta. English factories were established throughout Bengal. The port in Fort William became one of the most important British naval bases in Asia from where expeditions were sent to China and Southeast Asia. The English language began to be used for commerce and government in Bengal.[88]

French settlements (1692–1952)

[edit]The French establishments in India included colonies and factories in Bengal. After permission from Mughal viceroy Shaista Khan in 1692, the French set up a settlement in Chandernagore. The French also had a large presence in Dhaka, where a neighbourhood called Farashganj developed in the old city. One of the notable properties of the French included the land of the Ahsan Manzil, where the French administrative building was located. The property was sold to Bengali aristocrats, who exchanged the property several times until it became the property of the Dhaka Nawab Family. The French built a garden in Tejgaon. Cossimbazar and Balasore also hosted French factories.[91]

The French took the side of Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah during the Battle of Plassey in 1757. Eventually, the French presence in Bengal was only restricted to the colony of Chandernagore, which was administered by the governor in Pondicherry. After India's independence in 1947, a referendum in Chandernagore gave a mandate to end colonial rule. The French transferred sovereignty in 1952. In 1955, Chandernagore became part of the Indian state of West Bengal.

Danish settlements (1625–1845)

[edit]The first settlement of the Danish East India Company in Bengal was established in Pipli in 1625. The Danish company later gained permission from Nawab Alivardi Khan to establish a trading post in Serampore in 1755. The first representative of the Danish crown was appointed in 1770. The town was named Fredericknagore. The Danish also operated colonies on the Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal. Territories in Bengal and the Bay of Bengal were part of Danish India until 1845, when Danish colonies were ceded to Britain.

Austrian settlement (1700s)

[edit]The Ostend Company of the Austrian Empire operated a settlement in Bankipur, Bengal during the 18th century.

British East India Company (1772–1858)

[edit]

When the East India Company began strengthening the defences at Fort William (Calcutta), the Nawab, Siraj Ud Daulah, at the encouragement of the French, attacked. Under the leadership of Robert Clive, British troops and their local allies captured Chandernagore in March 1757 and seriously defeated the Nawab on 23 June 1757 at the Battle of Plassey, when the Nawab's soldiers betrayed him. The Nawab was assassinated in Murshidabad, and the British installed their own Nawab for Bengal and extended their direct control in the south. Chandernagore was restored to the French in 1763. The Bengalis attempted to regain their territories in 1765 in alliance with the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II, but were defeated again at the Battle of Buxar (1765). As part of the treaty with the British East India Company, East India Company was given the right to collect taxes from the province. Thus, the company became imperial tax collector, while the local Mughal Emperor appointed Nawabs continued to govern the province. In 1772 this arrangement of local rule was abolished and East India Company took complete control of the province. The center of Indian culture and trade shifted from Delhi to Calcutta when the Mughal Empire fell.

Capital amassed from Bengal by the East India Company was invested in various industries such as textile manufacturing in Great Britain during the initial stages of the Industrial Revolution.[12][13][14][15] Company policies in Bengal also led to the deindustrialization of the Bengali textile industry during Company rule.[12][14]

During the period of Company rule, a devastating famine occurred 1770, which killed millions. The famine devastated the region as well as the economy of the East India Company, forcing them to rely on subsidies from the British government, an act which would contribute to the American Revolution.[92]

British crown rule (1858–1947)

[edit]

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 replaced rule by the Company with the direct control of Bengal by the British Crown. Fort William continued to be the capital of British-held territories in India. The Governor of Bengal was concurrently the Governor-General of India for many years. In 1877, when Victoria took the title of "Empress of India", the British declared Calcutta the capital of the British Raj. The colonial capital developed in Calcutta's municipality, which served as the capital of India for decades. A centre of rice cultivation and the world's main source of jute fibre; Bengal was one of India's largest industrial centers. From the 1850s, industry was centered around the capital Calcutta. The railway was created in Britain in 1825. It was introduced in the United States in 1833, Germany in 1835, Italy in 1839, France in 1844 and Spain in 1848. The British government introduced the railway to Bengal in 1854.[93] Several rail companies were established in Bengal during the 19th century, including the Eastern Bengal Railway and Assam Bengal Railway. The largest seaport in British Bengal was the Port of Calcutta, one of the busiest ports in the erstwhile British Empire. The Calcutta Stock Exchange was established in 1908. Other ports in Bengal included the Port of Narayanganj, the Port of Chittagong and the Port of Dhaka. Bengali ports were often free trade ports which welcomed ships from across the world. There was extensive shipping with British Burma. Two universities were established in Bengal during British rule, including the University of Calcutta and the University of Dacca. Numerous colleges and schools were established in each district. Most of the Bengali population nevertheless remained dependent on agriculture, and despite Bengali social and political leaders playing a major role in Indian political and intellectual activity, the province included some very undeveloped districts.

The Bengal Presidency had the highest gross domestic product in British India.[94] Bengal hosted the most advanced cultural centers in British India.[95] A cosmopolitan, eclectic cultural atmosphere took shape. There were many anglophiles, including the Naib Nazim of Dhaka. A Portuguese missionary published the first book on Bengali grammar. A Hindu scholar produced a Bengali translation of the Quran. However, Bengalis were also divided by religion due to the political situation in the rest of India.

Bengal renaissance

[edit]

The Bengal renaissance refers to a social reform movement during the 19th and early 20th centuries in the region of Bengal in undivided India during the period of British rule. Historian Nitish Sengupta describes it as having started with reformer and humanitarian Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1775–1833), and ended with Asia's first Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941).[96] This flowering of religious and social reformers, scholars, and writers is described by historian David Kopf as "one of the most creative periods in Indian history".[97]

Bengal Legislative Council (1862–1947)

[edit]The Bengal Legislative Council was the principal lawmaking body in the province. It was created by the Indian Councils Act 1861 and reformed under the Indian Councils Act 1892, the Indian Councils Act 1909, the Government of India Act 1919 and the Government of India Act 1935. Initially an advisory council with mostly European members, native Bengali representation gradually increased in the early 20th century. In 1935, it became the upper house of the provincial legislature alongside the lower house in the Bengal Legislative Assembly. The Governor of Bengal, who was concurrently the Governor-General of India, often sat on the council.

Eastern Bengal and Assam (1905–1912)

[edit]

The British government argued that Bengal, being India's most populous province, was too large and difficult to govern. Bengal was divided by the British rulers for administrative purposes in 1905 into an overwhelmingly Hindu west (including present-day Bihar and Odisha) and a predominantly Muslim east (including Assam). Hindu – Muslim conflict became stronger through this partition. While Hindu Indians disagreed with the partition saying it was a way of dividing a Bengal which is united by language and history, Muslims supported it by saying it was a big step forward for Muslim society where Muslims will be majority and they can freely practice their religion as well as their culture. But owing to strong Hindu agitation, the British reunited East and West Bengal in 1912, and made Bihar and Orissa a separate province

The short lived province of Eastern Bengal and Assam provided impetus to a growing movement for self-determination among British-Indian Muslim subjects. The All India Muslim League was created during a conference on liberal education hosted by the Nawab of Dhaka in Eastern Bengal and Assam. The Eastern Bengal and Assam Legislative Council was the lawmaking body of the province.

Rebel activities

[edit]

Bengal played a major role in the Indian independence movement (including the Pakistan movement), in which revolutionary groups such as Anushilan Samiti and Jugantar were dominant. Bengalis also played a notable role in the Indian independence movement. Many of the early proponents of independence, and subsequent leaders in movement were Bengalis. Some notable freedom fighters from Bengal were Chittaranjan Das, Surendranath Banerjee, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, Prafulla Chaki, Bagha Jatin, Khudiram Bose, Surya Sen, Binoy–Badal–Dinesh, Sarojini Naidu, Batukeshwar Dutt, Aurobindo Ghosh, Rashbehari Bose, M.N. Roy, Muzaffar Ahmed and many more. Some of these leaders, such as Netaji, did not subscribe to the view that non-violent civil disobedience was the only way to achieve Indian Independence, and allied with Japan to fight against the British. During the Second World War Netaji escaped to Germany from house arrest in India and there he founded the Indian Legion an army to fight against the British Government, but the turning of the war compelled him to come to South-East Asia and there he became the co-founder and leader of the Indian National Army (distinct from the army of British India) that challenged British forces in several parts of India. He was also the head of state of a parallel regime named 'The Provisional Government of Free India' or Arzi Hukumat-e-Azad Hind, that was recognised and supported by the Axis powers. Bengal was also the fostering ground for several prominent revolutionary organisations. A large number of Bengalis died in the independence struggle and many were exiled in Cellular Jail, the much dreaded prison located in Andaman.

Bengal Legislative Assembly (1937–1947)

[edit]

The Bengal Legislative Assembly was British India's largest legislature. It was created by the Government of India Act 1935 as the lower house of the provincial parliament. The assembly was elected on the basis of the so-called "separate electorate" system created by the Communal Award. Seats were reserved for different religious, social and professional communities. Major parties in the assembly included the All India Muslim League, the Farmers and Tenants Party, the Indian National Congress, the Swaraj Party and the Hindu Mahasabha. The Prime Minister of Bengal was a member of the assembly.

Second World War

[edit]Bengal was used as a base for Allied Forces during World War II. Bengal was strategically important during the Burma Campaign and Allied assistance to the Republic of China to fight off the Japanese invasions. The Imperial Japanese Air Force bombed Chittagong in April and May 1942; and Calcutta in December 1942. The Japanese aborted a planned invasion of Bengal from Burma. The Ledo Road was constructed between Bengal and China through Allied controlled areas in northern Burma to supply the forces led by Chiang Kai Shek. Units of the United States Armed Forces were stationed in Chittagong Airfield during the Burma Campaign 1944-1945.[98] Commonwealth forces included troops from Britain, India, Australia and New Zealand.

The Bengal famine of 1943 occurred during World War II and caused the death of an estimated 2.1–3 million people.

Partition of Bengal (1947)

[edit]The partition of Bengal in 1947 left a deep impact on the people of Bengal. The breakdown of Hindu-Muslim unity caused the All India Muslim League to demand the partition of India in line with the Lahore Resolution, which called for Bengal to be included in a Muslim-majority homeland. Hindu nationalists in Bengal were determined to make Hindu-majority districts a part of the Indian dominion. A majority of members in the Bengal Legislative Assembly voted to keep Bengal undivided. The Prime Minister of Bengal, supported by Hindu and Muslim politicians, proposed a United Bengal as a sovereign state. However, the Indian National Congress and the Hindu Mahasabha on one side and the Muslim League on the other forced the British viceroy Earl Mountbatten to partition Bengal along religious lines. As a result, Bengal was divided into the state of West Bengal of India and the province of East Bengal under Pakistan, renamed East Pakistan in 1955. The Sylhet region in Assam joined East Bengal after a referendum on 6 July 1947.

Post-partition and contemporary era

[edit]West Bengal (India)

[edit]See also

[edit]Groups in West Bengal (Population: 10 crores West Bengalis) (2021)

Groups among the Bengalis of West Bengal (Percentage: 86.5% Bengalis of West Bengal) (2021)

References

[edit]- ^ a b Yang, Bin (2008). Between Winds and Clouds: The Making of Yunnan (PDF). Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14254-0. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ "Silk Road and Muslin Road". The Independent. Dhaka. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ a b "Bengal". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ Richard M. Eaton (31 July 1996). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760. University of California Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-520-20507-9.

- ^ David Lewis (31 October 2011). Bangladesh: Politics, Economy and Civil Society. Cambridge University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-139-50257-3.

In 1346 ... what became known as the Bengal Sultanate began and continued for almost two centuries.

- ^ Syed Ejaz Hussain (2003). The Bengal Sultanate: Politics, Economy and Coins (A.D. 1205–1576). Manohar. p. 325. ISBN 978-81-7304-482-3.

The rulers of the Sultanate Bengal are often blamed for promoting Islam as state sponsored religion.

- ^ María Dolores Elizalde; Wang Jianlang (6 November 2017). China's Development from a Global Perspective. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 57–73. ISBN 978-1-5275-0417-2.

- ^ "Isa Khan". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ^ a b Indrajit Ray (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757–1857). Routledge. pp. 57, 90, 174. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ^ Lawrence E. Harrison, Peter L. Berger (2006). Developing cultures: case studies. Routledge. p. 158. ISBN 9780415952798. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Which India is claiming to have been colonised?". The Daily Star (Opinion). 31 July 2015. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d Tong, Junie T. (2016). Finance and Society in 21st Century China: Chinese Culture Versus Western Markets. CRC Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-317-13522-7.

- ^ a b Esposito, John L., ed. (2004). "Great Britain". The Islamic World: Past and Present. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-19-516520-3. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d Ray, Indrajit (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757-1857). Routledge. pp. 7–10. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ^ a b Shombit Sengupta, Bengals plunder gifted the British Industrial Revolution Archived 1 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Financial Express, 8 February 2010

- ^ a b Blood, Peter R. (1989). "Early History, 1000 B.C.–A.D. 1202". In Heitzman, James; Worden, Robert (eds.). Bangladesh: A Country Study. Washington, DC: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 4. Archived from the original on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ^ Ahmed, Helal Uddin (2012). "History". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ Keay, John (2000). India: A History. Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-87113-800-2.

In C1020 ... launched Rajendra's great northern escapade ... peoples he defeated have been tentatively identified ... 'Vangala-desa where the rain water never stopped' sounds like a fair description of Bengal in the monsoon.

- ^ Allan, J.; Haig, T. Wolseley; Dodwell, H. H. (1934). Dodwell, H. H. (ed.). The Cambridge Shorter History of India. Cambridge University Press. p. 145. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

[Rājendra Chola I], after conquering eastern Bengal (Vangāladesa),

- ^ Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999) [First published 1988]. Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. p. 281. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- ^ Ahmed, Salahuddin (2004). Bangladesh: Past and Present. APH Publishing. p. 23. ISBN 978-8176484695. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ^ "But the most important development of this period was that the country for the first time received a name, ie Bangalah." Banglapedia: Islam, Bengal Archived 23 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sircar, D.C. (1971) [First published 1960]. Studies in the Geography of Ancient and Medieval India (2nd ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. p. 139. ISBN 978-81-208-0690-0. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ^ Land of Two Rivers, Nitish Sengupta

- ^ a b c Bharadwaj, G (2003). "The Ancient Period". In Majumdar, RC (ed.). History of Bengal. B.R. Publishing Corp.

- ^ a b c Eaton, R.M. (1996). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520205079. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Lewis, David (2011). Bangladesh: Politics, Economy and Civil Society. Cambridge University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-1139502573.

- ^ Pieris, Sita; Raven, Ellen (2010). ABIA: South and Southeast Asian Art and Archaeology Index. Vol. Three. Brill. p. 116. ISBN 978-9004191488.

- ^ Alam, Shafiqul (2012). "Mahasthan". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ^ Ghosh, Suchandra (2012). "Pundravardhana". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 23 June 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ^ "Sri Lanka – History". Encyclopædia Britannica. 14 February 1966. Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ "Facts about the Ancient Greeks: who was Homer, which gods did the ancient Greeks believe in, what was life like in Ancient Greece?". History Extra. 23 August 2018. Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ Olivelle, Patrick (2006). Between the Empires: Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE. Oxford University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0199775071.

- ^ Ring, Trudy; Salkin, Robert M.; La Boda, Sharon (1994). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. Taylor & Francis. p. 186. ISBN 978-1884964046.

- ^ Raychaudhuri, H. C. (1988) [1967]. "India in the Age of the Nandas". In K. A. Nilakanta Sastri (ed.). Age of the Nandas and Mauryas (Second ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-81-208-0466-1. Archived from the original on 17 August 2023. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ Bronkhorst, Johannes (2011). Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism. BRILL. p. 12. ISBN 978-90-04-20140-8.

- ^ Raychaudhuri, H. C. (1988) [1967]. "India in the Age of the Nandas". In K. A. Nilakanta Sastri (ed.). Age of the Nandas and Mauryas (Second ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 17. ISBN 978-81-208-0466-1. Archived from the original on 17 August 2023. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D. (December 2006). "East–West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 223. ISSN 1076-156X. Archived from the original on 20 May 2019. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ Kulke, H.; Rothermund, D. (2004) [First published 1986]. A History of India (4th ed.). Routledge. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-415-32920-0.

- ^ Bhandari, Shirin (5 January 2016). "Dinner on the Grand Trunk Road". Roads & Kingdoms. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ Raychaudhuri, Hemchandra (1996). Political history of ancient India : from the accession of Parikshit to the extinction of the Gupta dynasty. Internet Archive. Delhi; New York : Oxford University Press. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-19-563789-2.

A passage of Pliny clearly suggests that the "Palibothri," i.e., the rulers of Pataliputra, dominated the whole tract along the Ganges. That the Magadhan kings retained their hold on Bengal as late as the time of Aśoka is suggested by the testimony of the Divyavadāna and of Hiuen Tsang who saw Stupas of that monarch near Tamralipti and Karnasuvarna (in West Bengal), in Samataṭa (East Bengal) as well as in Pundravardhana (North Bengal).

- ^ Chakrobarty, Ashim Kumar. Life In Ancient Bengal Before The Rise Of The Palas. p. 14.

A large number of monasteries had been established in different parts of Bengal (Samatata, Pundravardhana, Tamralipta etc.) during the time of Asoka. This is known from Hiuen Tasng who had seen them when he visited Bengal... In Asoka's time Tamralipta was the chief port of the Magadhan empire and the communication between Ceylon and Magadha was maintained through Tamralipta. Asoka paid his visit to Bengal and at least once he came to Tamralipta. From the Ceylonese chronicle, the Mahavamsa, we come to know how Asoka visited Tamralipta on the occasion of the voyage of Mahendra and Sanghamitra with the holy branch of the Bodhi tree to Sinhala (modern Srilanka) at the time of the rule of the pious king Devanampriya Tissa of Ceylon .

- ^ Sastri, Hirananda (1931). Epigraphia Indica vol.21. pp. 83–89.

- ^ Hossain, Md. Mosharraf, pp. 56–65.

- ^ Majumdar, Susmita Basu (9 June 2023). Mahasthan Record Revisited: Querying the Empire from a Regional Perspective. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-90518-2.

- ^ "The Age of the Guptas and After". Washington State University. 6 June 1999. Archived from the original on 6 December 1998. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- ^ Ore, Oystein (1988). Number Theory and Its History. Courier Dover Publications. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-486-65620-5.

- ^ "Gupta dynasty (Indian dynasty)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- ^ "Gupta Rule". Banglapedia. 5 May 2014. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ William J. Topich; Keith A. Leitich (9 January 2013). The History of Myanmar. ABC-CLIO. pp. 17–22. ISBN 978-0-313-35725-1.

- ^ "Harikela". Banglapedia. 5 May 2014. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ Trudy Ring; Noelle Watson; Paul Schellinger (12 November 2012). Asia and Oceania: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. p. 186. ISBN 978-1-136-63979-1.

- ^ Encyclopaedia of North-East India by T. Raatan p.143

- ^ Nadia' Jillar Purakirti by Archaeological Survey of India, West Bengal, 1975

- ^ Roy, Niharranjan (1993). Bangalir Itihas: Adiparba Calcutta: Dey's Publishing, ISBN 81-7079-270-3, pp.408–9

- ^ Richard M. Eaton (1996). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760. University of California Press. pp. 32–34. ISBN 978-0-520-20507-9.

- ^ Shoaib Daniyal (15 November 2016). "History revisited: How Tughlaq's currency change led to chaos in 14th century India". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ "Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah". Banglapedia. 5 May 2014. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ "Alauddin Ali Shah". Banglapedia. 5 May 2014. Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ Battuta, Muhammad Ibn (2018). In Bengal – Muhammad Ibn Battuta. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 9781986693011. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ J. Wise (1873). "Note on Sháh Jalál, the patron saint of Silhaț". Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. 42 (3): 280–281. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ "Humayun". Banglapedia. 5 April 2014. Archived from the original on 22 June 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ Acharyya, N.N. (1966). The History of Medieval Assam, from the Thirteenth to the Seventeenth Century. New Delhi: Omsons Publ. p. 205.

- ^ John F. Richards (1995), The Mughal Empire, page 190, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Richard Maxwell Eaton (1996), The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760, page 202 Archived 4 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine, University of California Press

- ^ Om Prakash, "Empire, Mughal Archived 18 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine", History of World Trade Since 1450, edited by John J. McCusker, vol. 1, Macmillan Reference USA, 2006, pp. 237–240, World History in Context. Retrieved 3 August 2017

- ^ John F. Richards (1995), The Mughal Empire, page 202, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Ray, Indrajit (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757–1857). Routledge. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- ^ Kirti N, Chaudhuri (2006). The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company: 1660-1760. Cambridge University Press. p. 253. ISBN 9780521031592.

- ^ P.J, Marshall. Bengal: The British Bridgehead: Eastern India 1740-1828. Cambridge University Press. p. 73. ISBN 9780521028226.

- ^ a b Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib. Penguin Books India. 2011. pp. 158–163. ISBN 9780143416784.

- ^ P. J. Marshall (2006) [First published 1987]. Bengal: The British Bridgehead: Eastern India 1740–1828. Cambridge University Press. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-0-521-02822-6.

- ^ a b Kirti N. Chaudhuri (2006) [First published 1978]. The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company: 1660–1760. Cambridge University Press. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-521-03159-2.

- ^ C. C. Davies (1957). "Chapter XXIII: Rivalries in India". In J. O. Lindsay (ed.). The New Cambridge Modern History. Vol. VII. Cambridge University Press. p. 555. ISBN 978-0-521-04545-2. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Ghosh, Paschimbanger Sanskriti, Volume II, pp. 224

- ^ Ghosh, Dr. Sujit (2016). Colonial Economy in North Bengal: 1833–1933. Kolkata: Paschimbanga Anchalik Itihas O Loksanskriti Charcha Kendra. p. 101. ISBN 978-81-926316-6-0.

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India, New Edition (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1908–1931), Vol. 9, p. 102

- ^ "Arabs, The". Banglapedia. 17 June 2014. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ "Iranians, The". Banglapedia. 8 June 2014. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ "Armenians, The". Banglapedia. 17 June 2014. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ "Turks, The". Banglapedia. 31 December 2014. Archived from the original on 3 February 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ "Portuguese, The". Banglapedia. 9 February 2015. Archived from the original on 25 April 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ "Rakhain, The". Banglapedia. 8 March 2015. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ "Manipuri, The". Banglapedia. 2 March 2015. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ The Portuguese, Banglapedia, archived from the original on 25 April 2020, retrieved 21 May 2018

- ^ Rahim, AK (25 January 2014). "Você fala Bangla?". Dhaka Tribune. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ^ Om Prakash, "Empire, Mughal", History of World Trade Since 1450, edited by John J. McCusker, vol. 1, Macmillan Reference USA, 2006, pp. 237–240, World History in Context

- ^ a b c "English". Banglapedia. 8 June 2014. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ Osmany, Shireen Hasan; Mazid, Muhammad Abdul (2012). "Chittagong Port". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 9 December 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ^ Hunter, William Wilson (1908). Imperial Gazetteer of India. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 308, 309. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ "French, The". Banglapedia. 5 May 2014. Archived from the original on 22 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ Willem van Schendel (12 February 2009). A History of Bangladesh. Cambridge University Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780511997419.

- ^ "Railway". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ^ "Reimagining the Colonial Bengal Presidency Template (Part I)". Daily Sun. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ^ James B. Minahan (30 August 2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-59884-660-7.

- ^ Nitish Sengupta (2001). History of the Bengali-speaking People. UBS Publishers' Distributors. p. 211. ISBN 978-81-7476-355-6.

The Bengal Renaissance can be said to have started with Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1775-1833) and ended with Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941).

- ^ Kopf, David (December 1994). "Amiya P. Sen. Hindu Revivalism in Bengal 1872". American Historical Review (Book review). 99 (5): 1741–1742. doi:10.2307/2168519. JSTOR 2168519.

- ^ Maurer, Maurer. Air Force Combat Units of World War II. Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Office of Air Force History, 1983. ISBN 0-89201-092-4

Further reading

[edit]- Mandal, Mahitosh (2022). "Dalit Resistance during the Bengal Renaissance: Five Anti-Caste Thinkers from Colonial Bengal, India". Caste: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion. 3 (1): 11–30. doi:10.26812/caste.v3i1.367. Archived from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- Salim, Gulam Hussain; tr. from Persian; Abdus Salam (1902). Riyazu-s-Salatin: History of Bengal. Asiatic Society, Baptist Mission Press.

- Majumdar, R. C. The History of Bengal ISBN 81-7646-237-3

- Amiya Sen (1993). Hindu Revivalism in Bengal 1872–1905: Some Essays in Interpretation. Oxford University Press.

- Abdul Momin Chowdhury (1967) Dynastic History of Bengal, c. 750–1200 A.D, Dacca: The Asiatic Society of Pakistan, 1967, Pages: 310, ASIN: B0006FFATA

- Iftekhar Iqbal (2010) The Bengal Delta: Ecology, State and Social Change, 1840–1943, Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies, Palgrave Macmillan, Pages: 288, ISBN 0230231837

- M. Mufakharul Islam (edited) (2004) Socio-Economic History of Bangladesh: essays in memory of Professor Shafiqur Rahman, 1st Edition, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, OCLC 156800811

- M. Mufakharul Islam (2007), Bengal Agriculture 1920–1946: A Quantitative Study, Cambridge South Asian Studies, Cambridge University Press, Pages: 300, ISBN 0521049857

- Meghna Guhathakurta & Willem van Schendel (Edited) (2013) The Bangladesh Reader: History, Culture, Politics (The World Readers), Duke University Press Books, Pages: 568, ISBN 0822353040

- Sirajul Islam (edited) (1997) History of Bangladesh 1704–1971 (Three Volumes: Vol 1: Political History, Vol 2: Economic History Vol 3: Social and Cultural History), 2nd Edition (Revised New Edition), The Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Pages: 1846, ISBN 9845123376

- Sirajul Islam (Chief Editor) (2003) Banglapedia: A National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh.(10 Vols. Set), (written by 1300 scholars & 22 editors) The Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Pages: 4840, ISBN 9843205855

- Samares Kar: The Millennia Long Migration into Bengal: Rich Genetic Material and Enormous Promise in the Face of Chaos, Corruption, and Criminalization. In: Spaces & Flows: An International Journal of Urban & Extra Urban Studies. Vol. 2 Issue 2, 2012, S. 129–143 (Fulltext Archived 21 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine see ResearchGate Network).

- Dr. Sujit Ghosh, (2016) Colonial Economy in North Bengal: 1833–1933, Kolkata: Paschimbanga Anchalik Itihas O Loksanskriti Charcha Kendra, ISBN 978-81-926316-6-0

- Om Prakash (1985), The Dutch East India Company and the Economy of Bengal 1630-1720, Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-69105-447-6