Anomaly scan

| Anomaly scan | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Anatomy scan, second-trimester ultrasound, 20-week ultrasound, level 2 ultrasound |

| Purpose | To evaluate fetal anatomy and size |

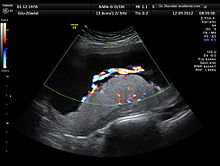

The anomaly scan, also sometimes called the anatomy scan, 20-week ultrasound, or level 2 ultrasound, evaluates anatomic structures of the fetus, placenta, and maternal pelvic organs. This scan is an important and common component of routine prenatal care.[1] The function of the ultrasound is to measure the fetus so that growth abnormalities can be recognized quickly later in pregnancy, to assess for congenital malformations and multiple pregnancies, and to plan method of delivery.[2]

Procedure

[edit]This scan is conducted between 18 and 22 weeks' gestation, but most often performed at 19 weeks, as a component of routine prenatal care. Prior to 18 weeks' gestation, the fetal organs may be of insufficient size and development to allow for ultrasound evaluation. Scans performed beyond 22 weeks' gestation may limit the ability to seek pregnancy termination, depending on local legislation.[1]

Two-dimensional (2D) is used to evaluate fetal structures, placenta, and amniotic fluid volume. Maternal pelvic organs are also evaluated. Views are obtained using an abdominal ultrasound probe, but a vaginal ultrasound probe may also be used to evaluate for placenta previa and cervical length. Three-dimensional (3D) ultrasound is not recommended for routine use during anomaly scan, but 3D ultrasound may be used to further evaluate suspected abnormalities in specific fetal features.[3]

Components

[edit]

A standard anatomy scan typically includes:[4]

- Fetal number, including number of amnionic sacs and chorionic sacs for multiple gestations

- Fetal cardiac activity

- Fetal position relative to the uterus and cervix

- Location and appearance of the placenta, including site of umbilical cord insertion

- Amnionic fluid volume

- Gestational age assessment

- Fetal weight estimation

- Fetal anatomical survey

- Evaluation of the maternal uterus, tubes, ovaries, and bladder when appropriate[4]

Medical uses

[edit]Second-trimester ultrasound screening for aneuploidies, such as Edwards syndrome and Patau syndrome, is based on looking for soft markers and some predefined structural abnormalities. Soft markers are variations from normal anatomy, which are more common in aneuploid fetuses compared to euploid ones. These markers are often not clinically significant and do not cause adverse pregnancy outcomes, but used in order to decide whether additional tests, which will be more accurate, are needed.[5] Placental evaluation is vital for planning method of delivery, as attempting natural childbirth can cause fatal amounts of blood loss in the mother if the placenta is covering the cervix (placenta praevia) and significantly increases the risk of stillbirth. Additionally, placental and umbilical cord abnormalities are also associated with certain fetal genetic abnormalities.[3]

| Fetal Conditions[6] | Placental Conditions[3] | Maternal Conditions[3] |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Sex determination

[edit]Fetal sex is often noted during the anomaly scan, but can also be detected during the quad scan. However, performing an ultrasound for the sole purpose of determining fetal sex without a medical indication is not recommended.[1]

Limitations

[edit]Although ultrasound is a useful screening tool for fetal anomalies, the sensitivity of this scan is highly variable and potentially detects only 40% of all fetal anomalies. The ability of this scan to detect structural fetal abnormalities depends on a variety of factors. These factors include the severity of the anomaly, the background risk of the study population, gestational age at time of scan, the expertise of the ultrasound technician and interpreting obstetrician, and maternal obesity.[1]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (December 2016). "Practice Bulletin No. 175: Ultrasound in Pregnancy". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 128 (6): e241 – e256. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001815. ISSN 0029-7844. PMID 27875472. S2CID 39291307.

- ^ "Practice guidelines for performance of the routine mid-trimester fetal ultrasound scan" (PDF). ISUOG.org. Retrieved December 4, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Creasy and Resnik's maternal-fetal medicine : principles and practice. Creasy, Robert K.,, Resnik, Robert,, Greene, Michael F.,, Iams, Jay D.,, Lockwood, Charles J. (Seventh ed.). Philadelphia, PA. 17 September 2013. ISBN 978-0-323-18665-0. OCLC 859526325.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Cunningham, F; Leveno, KJ; Bloom, SL; Spong, CY; Dashe, JS; Hoffman, BL; Casey BM, BM; Sheffield, JS (2013). "Fetal Imaging". Williams Obstetrics, Twenty-Fourth Edition. McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Zare Mehrjardi, Mohammad; Keshavarz, Elham (2017-04-16). "Prefrontal Space Ratio—A Novel Ultrasound Marker in the Second Trimester Screening for Trisomy 21: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Journal of Diagnostic Medical Sonography. 33 (4): 269–277. doi:10.1177/8756479317702619.

- ^ NHS Choices. "Mid-pregnancy anomaly scan - Pregnancy and baby - NHS Choices". www.nhs.uk. Retrieved 2017-12-04.