Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station

Amundsen–Scott Station | |

|---|---|

| Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station | |

The Amundsen–Scott Station in 2018. In the foreground is Destination Alpha, one of the two main entrances. | |

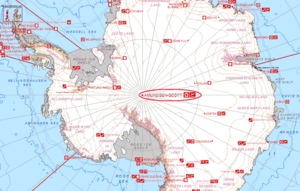

A map of Antarctica showing the location of the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station (circled) | |

Location of Amundsen–Scott Station at the South Pole in Antarctica | |

| Coordinates: 90°S 0°E / 90°S 0°E | |

| Country | United States |

| Location in | Geographic South Pole, Antarctic Plateau |

| Administered by | United States Antarctic Program by the National Science Foundation |

| Established | November 1956 |

| Named for | Roald Amundsen and Robert F. Scott |

| Elevation | 9,301 ft (2,835 m) |

| Population | |

| • Summer | 150 |

| • Winter | 49 |

| Time zone | UTC+12 (NZST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+13 (NZDT) |

| UN/LOCODE | AQ AMS |

| Type | All year-round |

| Period | Annual |

| Status | Operational |

| Activities | List

|

| Facilities[2][3] | List

|

| Website | Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station |

The Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station is a United States scientific research station at the South Pole of the Earth. It is the southernmost point under the jurisdiction (not sovereignty) of the United States. The station is located on the high plateau of Antarctica at 9,301 feet (2,835 m) above sea level. It is administered by the Office of Polar Programs of the National Science Foundation, specifically the United States Antarctic Program (USAP). It is named in honor of Norwegian Roald Amundsen and Briton Robert F. Scott, who led separate teams that raced to become the first to the pole in the early 1900s.

The original Amundsen–Scott Station was built by Navy Seabees for the federal government of the United States during November 1956, as part of its commitment to the scientific goals of the International Geophysical Year, an effort lasting from January 1957 to June 1958 to study, among other things, the geophysics of the polar regions of Earth.

Before November 1956, there was no permanent artificial structure at the pole, and practically no human presence in the interior of Antarctica. The few scientific stations in Antarctica were near its coast. The station has been continuously occupied since it was built and has been rebuilt, expanded, and upgraded several times.

The station is the only inhabited place on the surface of the Earth from which the Sun is continuously visible for six months; it is then continuously dark for the next six months, with approximately two days of averaged dark and light, twilight, namely the equinoxes. These are, in observational terms, called one extremely long "day" and one equally long "night". During the six-month "day", the angle of elevation of the Sun above the horizon varies incrementally. The Sun reaches a rising position throughout the September equinox, and then it is apparent highest at the December solstice which is summer solstice for the south, setting on the March equinox.

During the six-month polar night, air temperatures can drop below −73 °C (−99 °F) and blizzards are more frequent. Between these storms, and regardless of the weather for wavelengths unaffected by drifting snow, the roughly 5+3⁄4 months of ample darkness and dry atmosphere make the station an excellent site for astronomical observations.

The number of scientific researchers and members of the support staff housed at the Amundsen–Scott Station has always varied seasonally, with a peak population of around 150 in the summer operational season from October to February. In recent years, the wintertime population has been around 50 people. Supplies come seasonally, during the warm season by Air or by the South Pole Traverse after it is opened; this traverse links the station to Scott Base and McMurdo Station on Ross Island since 2005 and reduces the amount of flights in. Much of the logistical support for the South Pole Station flows through McMurdo which has the farthest south port, Winter's Bay.

Structures

[edit]Original station (1957–2010)

[edit]

The original South Pole station is now referred to as "Old Pole". The station was constructed by U.S. Navy Seabees led by LTJG Richard Bowers, the eight-man Advance Party being transported by the VX-6 Air Squadron in two R4Ds on November 20, 1956. The U.S. Eighteenth Air Force's C-124 Globemaster IIs airdropped most of the equipment and building material. The buildings were constructed from prefabricated four-by-eight-foot modular panels. Exterior surfaces were four inches (10 cm) thick, with an aluminum interior surface, and a plywood exterior surface, sandwiching fiberglass. Skylights were the only windows in flat uniform roof levels, while buildings were connected by a burlap and chicken wire covered tunnel system. The last of the construction crew departed on January 4, 1957. The first wintering-over party consisted of eight IGY scientists led by Paul Siple and eight Navy support men led by LTJG John Tuck. Key components of the camp included an astronomical observatory, a Rawin Tower, a weather balloon inflation shelter, and a 1,000-foot (300 m) snow tunnel with pits for a seismometer and magnetometer. The lowest average temperatures recorded by the group were in the range −90 °F (−68 °C) to −99 °F (−73 °C), though as Siple points out, "even at −60 °F (−51 °C) I had seen men spitting blood because the capillaries of the bronchial tract frosted".[4]

On January 3, 1958, Sir Edmund Hillary's team from New Zealand, part of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, reached the station over land from Scott Base, followed shortly by Sir Vivian Fuchs' British scientific component.[5]

The buildings of Old Pole were assembled from prefabricated components delivered to the South Pole by air and airdropped. They were originally built on the surface, with covered wood-framed walkways connecting the buildings. Although snow accumulation in open areas at the South Pole is approximately 8 inches (20 cm) per year, wind-blown snow accumulates much more quickly in the vicinity of raised structures. By 1960, three years after the construction of the station, it had already been buried by 6 feet (1.8 m) of snow.[6]

The station was abandoned in 1975 and became deeply buried, with the pressure causing the mostly wooden roof to cave in. The station was demolished in December 2010, after an equipment operator fell through the structure doing snow stability testing for the National Science Foundation (NSF).[7][8] The area was being vetted for use as a campground for NGO guests.

Dome (1975–2010)

[edit]The station was moved in 1975 to the newly constructed Buckminster Fuller geodesic dome 160 feet (50 m) wide by 52 feet (16 m) high, with 46 by 79 feet (14 m × 24 m) steel archways. One served as the entry to the dome and it had a transverse arch that contained modular buildings for the station's maintenance, fuel bladders, power plant, snow melter, equipment and vehicles. Individual buildings within the dome contained the dorms, galley, recreational center, post office and labs for monitoring the upper and lower atmosphere and numerous other complex projects in astronomy and astrophysics. The station also included the Skylab, a box-shaped tower slightly taller than the dome. Skylab was connected to the Dome by a tunnel. The Skylab housed atmospheric sensor equipment and later a music room.

During the 1970–1974 summers, the Seabees constructing the dome were housed in Korean War era Jamesway huts. A hut consists of a wooden frame with a raised platform covered by canvas tarp. A double-doored vestibule was at each end. Although heated, the heat was not sufficient to keep them habitable during the winter. After several burned during the 1976–1977 summer, the construction camp was abandoned and later removed.

However, in the 1981–1982 season, extra civilian seasonal personnel were housed in a group of Jamesways known as the "summer camp". Initially consisting of only two huts, the camp grew to 11 huts housing about 10 people each, plus two recreational huts with bathroom and gym facilities. In addition, a number of science and berthing structures, such as the hypertats and elevated dormitory, were added in the 1990s, particularly for astronomy and astrophysics.

During the period in which the dome served as the main station, many changes to United States South Pole operation took place. From the 1990s on, astrophysical research conducted at the South Pole took advantage of its favorable atmospheric conditions and began to produce important scientific results. Such experiments include the Python, Viper, and DASI telescopes, as well as the 390-inch (10 m) South Pole Telescope. The DASI telescope has since been decommissioned and its mount used for the Keck Array.[9] The AMANDA / IceCube experiment makes use of the two-mile (3 km)-thick ice sheet to detect neutrinos which have passed through the earth. An observatory building, the Martin A. Pomerantz Observatory (MAPO), was dedicated in 1995. The importance of these projects changed the priorities in station operation, increasing the status of scientific cargo and personnel.

The 1998–1999 summer season was the last year that VXE-6 with its Lockheed LC-130s serviced the U.S. Antarctic Program. Beginning in 1999–2000, the New York Air National Guard 109th Airlift Wing took responsibility for the daily cargo and passenger flights between McMurdo Station and the South Pole during the summer.

During the winter of 1988 a loud crack was heard in the dome. Upon investigation it was discovered that the foundation base ring beams were broken due to being overstressed.[10]

The dome was dismantled in late 2009.[11] It was crated and given to the Seabees. As of 2025, the dome pieces are stored at Port Hueneme, California. The center oculus is suspended in a display at the Seabee Museum there.

-

The main entrance to the former geodesic dome ramped down from the surface level. The base of the dome was originally at the surface level of the ice cap, but the base had been slowly buried by snow and ice.

-

An aerial view of the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station taken in about 1983. The central dome is shown along with the arches, with various storage buildings, and other auxiliary buildings such as garages and hangars.

-

The dome in January 2009, as seen from the new elevated station.

-

Ceremonial South Pole (the dome in the background was dismantled in 2009–2010).

-

January 2010: The last section of the old dome, before it was removed the next day.

Elevated station (2008–present)

[edit]In 1992, the design of a new station began for an 80,000 sq ft (7,400 m2) building with two floor levels that cost US$150 million.[12] Construction began in 1999, adjacent to the Dome. The facility was officially dedicated on January 12, 2008, with a ceremony that included the de-commissioning of the old Dome station.[13] The ceremony was attended by a number of dignitaries flown in specifically for the day, including National Science Foundation Director Arden Bement, scientist Susan Solomon and other government officials. The entirety of building materials to complete the build of the new South Pole Station were flown in from McMurdo Station by the LC-130 Hercules aircraft and the 139th Airlift Squadron Stratton Air National Guard Base, Scotia, New York. Each plane brought 26,000 pounds (12,000 kg) of cargo each flight with the total weight of the building material being 24,000,000 pounds (11,000,000 kg).[14]

The new station included a modular design, to accommodate rises in population, and an adjustable elevation to prevent it from being buried in snow. Since roughly 8 inches (20 cm) of snow accumulates every year without ever thawing,[15][16] the building's designers included rounded corners and edges around the structure to help reduce snow drifts. The building faces into the wind with a sloping lower portion of wall. The angled wall increases the wind speed as it flows under the buildings, and passes above the snow-pack, causing the snow to be scoured away. This prevents the building from being quickly buried. Wind tunnel tests show that scouring will continue to occur until the snow level reaches the second floor.

Because snow gradually settles over time under its own weight, the foundations of the building were designed to accommodate substantial differential settling over any one wing in any one line or any one column. If differential settling continues, the supported structure will need to be jacked up and re-leveled. The facility was designed with the primary support columns outboard of the exterior walls so that the entire building can be jacked up a full floor level. During this process, a new section of column will be added over the existing columns then the jacks pull the building up to the higher elevation.[citation needed]

-

An aerial view of the Amundsen–Scott Station in January 2005. The older domed station is visible on the right-hand side of this photo.

-

The Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station during the 2007–2008 summer season.

-

A photo of the station at night. The new station can be seen in the far left, the electric power plant is in the center, and the old vehicle mechanic's garage in the lower right. The green light in the sky is part of the aurora australis.

Operation

[edit]

During the summer the station population is typically around 150. Most personnel leave by the middle of February, leaving a few dozen (39 in 2021) "winter-overs", mostly support staff plus a few scientists, who keep the station functional through the months of Antarctic night. The winter personnel are isolated between mid-February and late October. Wintering-over presents notorious dangers and stresses, as the station population is almost totally isolated. The station is completely self-sufficient during the winter, and powered by three generators running on JP-8 jet fuel. An annual tradition is a back-to-back-to-back viewing of The Thing from Another World (1951), The Thing (1982), and The Thing (2011) after the last flight has left for the winter.[17]

Research at the station includes glaciology, geophysics, meteorology, upper atmosphere physics, astronomy, astrophysics, and biomedical studies. In recent years, most of the winter scientists have worked for the IceCube Neutrino Observatory or for low-frequency astronomy experiments such as the South Pole Telescope and BICEP2. The low temperature and low moisture content of the polar air, combined with the altitude of over 9,000 feet (2,700 m), causes the air to be far more transparent on some frequencies than is typical elsewhere, and the months of darkness permit sensitive equipment to run constantly.

There is a small greenhouse at the station. The variety of vegetables and herbs in the greenhouse, which range from fresh eggplant to jalapeños, are all produced hydroponically, using only water and nutrients and no soil. The greenhouse is the only source of fresh fruit and vegetables during the winter.

Transportation

[edit]The station has a runway for aircraft (ICAO: NZSP), 12,000 feet (3,658 m) long. Between October and February, there are several flights per day of U.S. Air Force ski-equipped Lockheed LC-130 Hercules aircraft from the New York Air National Guard, 109 AW, 139AS Stratton Air National Guard via McMurdo Station to supply the station. Resupply missions are collectively termed Operation Deep Freeze.

There is a snow road over the ice sheet from McMurdo, the McMurdo-South Pole highway, which is 995 miles (1,601 km) long.

Communication

[edit]

Data access to the station is provided by NASA's TDRS-4 (non operational), 5 (not radio link to 90°), and 6 (not radio link to 90°) satellites: the DOD DSCS-3 satellite, and the commercial Iridium satellite constellation. For the 2007–2008 season, the TDRS relay (named South Pole TDRSS Relay or SPTR) was upgraded to support a data return rate of 50 Mbit/s, which comprises over 90% of the data return capability.[18][19] The TDRS-1 satellite formerly provided services to the station, but it failed in October 2009 and was subsequently decommissioned. Marisat and LES9 were also formerly used. In July 2016, the GOES-3 satellite was decommissioned due to it nearing the end of its supply of propellant and was replaced by the use of the DSCS-3 satellite, a military communications satellite. DSCS-3 can provide a 30 MB/s data rate compared to GOES-3's 1.5 MB/s. DSCS-3 and TDRS-4, 5, and 6 are used together to provide the main communications capability for the station. These satellites provide the data uplink for the station's scientific data as well as provide broadband internet and telecommunications access. Only during the main satellite events is the station's telephone system able to dial out. The commercial Iridium satellite is used when the TDRS and DSCS satellites are all out of range to give the station limited communications capability during those times. During those times, telephone calls may only be made on several Iridium satellite telephone sets owned by the station. The station's IT system also has a limited data uplink over the Iridium network, which allows emails less than 100 KB to be sent and received at all times and small critical data files to be transmitted. This uplink works by bonding the data stream over 12 voice channels. Non-commercial and non-military communication has been provided by amateur ham radio using primarily HF SSB links today but Morse code and other modes have been used, partly in experiments and mainly in bolstering esprit de corps and hobby-type uses. The USA sector has the amateur radio call sign prefix run of KC4 and AT; whereas Soviet/Russian stations are known to use 4K1 and others. The popularity of the hobby during the 1950-80s era saw many ham exchanges between South Polar ham stations and enthusiastic ham operators contacting there from world-wide locations. Over the years, ham radio has established needed emergency communication to Polar base personnel as well as recreational uses.[citation needed]

Astrophysics experiments at the station

[edit]

Cosmic Microwave Background Telescopes

- Python Telescope (1992–1997),[20] used to observe temperature anisotropies in the cosmic microwave background (CMB).[21]

- Viper telescope (1997–2000), used to observe temperature anisotropies in the CMB.[20] Was refitted with the ACBAR bolometer (2000-2008).[22]

- DASI (1999–2000), used to measure the temperature and power spectrum of the CMB.[23]

- The QUaD (2004–2009), used the DASI mount, used to make detailed observations of CMB polarization.[24][25]

- The BICEP1 (2006–2008) and BICEP2 (2010–2012) instruments were also used to observe polarization anisotropies in the CMB. BICEP3 was installed in 2015.[26]

- South Pole Telescope (2007–present), used to survey the CMB to look for distant galaxy clusters.[27]

- The Keck Array (2010–present), using the DASI mount,[9] is now used to continue work on the polarization anisotropies of the CMB.

Neutrino Experiments

- AMANDA (1997–2009) was an experiment to detect neutrinos.[28]

- IceCube (2010–present) is an experiment to detect neutrinos.[29]

- Radio Ice Cherenkov Experiment or RICE (1999–2012), an experiment to detect ultra high energy (UHE) neutrinos.

- Neutrino Array Radio Calibration or NARC (2008–2012), an upgrade of the RICE experiment.

- Askaryan Radio Array or ARA (2011–present), a successor of RICE, currently (as of 2022) under construction.

Climate

[edit]Typical of inland Antarctica, Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station experiences an ice cap climate (EF) with BWk precipitation patterns.[30] The peak season of summer lasts from December to mid February.

At the Amundsen–Scott the average annual precipitation is approximately 50 millimeters (2 inches), primarily falling as snow.[31] This low level of precipitation is characteristic of the Antarctic interior, where the combination of extremely low temperatures and limited moisture in the atmosphere results in an extremely arid climate with minimal snowfall.

| Climate data for Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | −14.8 (5.4) |

−20.6 (−5.1) |

−26.7 (−16.1) |

−27.8 (−18.0) |

−25.1 (−13.2) |

−28.8 (−19.8) |

−31.9 (−25.4) |

−32.8 (−27.0) |

−29.3 (−20.7) |

−25.1 (−13.2) |

−18.9 (−2.0) |

−12.3 (9.9) |

−12.3 (9.9) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | −19.3 (−2.7) |

−26.7 (−16.1) |

−35.4 (−31.7) |

−39.9 (−39.8) |

−37.7 (−35.9) |

−41.1 (−42.0) |

−40.6 (−41.1) |

−42.5 (−44.5) |

−38.2 (−36.8) |

−37.2 (−35.0) |

−27.0 (−16.6) |

−20.5 (−4.9) |

−18.2 (−0.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −25.9 (−14.6) |

−37.4 (−35.3) |

−49.2 (−56.6) |

−52.6 (−62.7) |

−52.8 (−63.0) |

−53.1 (−63.6) |

−55.2 (−67.4) |

−54.6 (−66.3) |

−54.1 (−65.4) |

−47.3 (−53.1) |

−34.9 (−30.8) |

−25.6 (−14.1) |

−45.2 (−49.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −28.1 (−18.6) |

−40.7 (−41.3) |

−53.6 (−64.5) |

−57.4 (−71.3) |

−57.7 (−71.9) |

−58.1 (−72.6) |

−60.2 (−76.4) |

−59.7 (−75.5) |

−58.9 (−74.0) |

−50.9 (−59.6) |

−37.2 (−35.0) |

−27.3 (−17.1) |

−49.1 (−56.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −29.5 (−21.1) |

−42.6 (−44.7) |

−56.4 (−69.5) |

−60.6 (−77.1) |

−61.1 (−78.0) |

−61.5 (−78.7) |

−63.7 (−82.7) |

−63.0 (−81.4) |

−62.2 (−80.0) |

−53.3 (−63.9) |

−38.8 (−37.8) |

−28.4 (−19.1) |

−52.2 (−62.0) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −34.9 (−30.8) |

−51.4 (−60.5) |

−66.2 (−87.2) |

−69.6 (−93.3) |

−70.2 (−94.4) |

−72.8 (−99.0) |

−72.3 (−98.1) |

−72.6 (−98.7) |

−73.6 (−100.5) |

−66.8 (−88.2) |

−48.8 (−55.8) |

−35.2 (−31.4) |

−75.3 (−103.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −41.1 (−42.0) |

−58.9 (−74.0) |

−71.1 (−96.0) |

−75.0 (−103.0) |

−78.3 (−108.9) |

−82.8 (−117.0) |

−80.6 (−113.1) |

−79.3 (−110.7) |

−79.4 (−110.9) |

−72.0 (−97.6) |

−55.0 (−67.0) |

−41.1 (−42.0) |

−82.8 (−117.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0.3 (0.01) |

0.6 (0.02) |

0.2 (0.01) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.2 (0.01) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.3 (0.01) |

2.3 (0.09) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 0.3 (0.1) |

0.5 (0.2) |

— | — | 0.3 (0.1) |

— | trace | — | — | — | — | 0.3 (0.1) |

1.3 (0.5) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1.6 |

| Average snowy days | 22.0 | 19.6 | 13.6 | 11.4 | 17.2 | 17.3 | 18.2 | 17.5 | 11.7 | 16.7 | 16.9 | 20.6 | 203.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 406.1 | 497.2 | 195.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 34.1 | 390.6 | 558.0 | 616.9 | 2,698.2 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 13.1 | 17.6 | 6.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 12.6 | 18.6 | 19.9 | 7.4 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru.net (temperatures, 1991-2020, extremes 1957–present)[32] [33] [34] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (Precipitation 1957–1988 and Sun 1978–1993),[35] NOAA (snowy days and snowfall data, 1961–1988)[36] | |||||||||||||

Media and events

[edit]

In 1991, Michael Palin visited the base on the eighth and final episode of his BBC Television documentary, Pole to Pole.[37][38]

On January 10, 1995, NASA, PBS, and NSF collaborated for the first live television broadcast from the South Pole, titled Spaceship South Pole.[39] During this interactive broadcast, students from several schools in the United States asked the scientists at the station questions about their work and conditions at the pole.[40]

In 1999, CBS News correspondent Jerry Bowen reported on camera in a talkback with anchors from the Saturday edition of CBS This Morning.

In 1999, the winter-over physician, Jerri Nielsen, found that she had breast cancer. She had to rely on self-administered chemotherapy, using supplies from a daring July cargo drop, then was picked up in an equally dangerous mid-October landing.

On May 11, 2000, astrophysicist Rodney Marks became ill while walking between the remote observatory and the base. He became increasingly sick over 36 hours, three times returning increasingly distressed to the station's doctor. Advice was sought by satellite, but Marks died on May 12, 2000, with his condition undiagnosed.[41][42] The National Science Foundation issued a statement that Rodney Marks had "apparently died of natural causes, but the specific cause of death had yet to be determined".[43] The exact cause of Marks' death could not be determined until his body was removed from Amundsen–Scott Station and flown off Antarctica for an autopsy.[44] Marks' death was due to methanol poisoning, and the case received media attention as the "first South Pole murder",[45] although there is no evidence that Marks died as the result of the act of another person.[46][47]

On 26 April 2001, Kenn Borek Air used a DHC-6 Twin Otter aircraft to rescue Dr. Ronald Shemenski from Amundsen–Scott.[48][49][50][51] This was the first ever rescue from the South Pole during polar winter.[52] To achieve the range necessary for this flight, the Twin Otter was equipped with a special ferry tank.

In January 2007, the station was visited by a group of high-level Russian officials, including FSB chiefs Nikolai Patrushev and Vladimir Pronichev. The expedition, led by polar explorer Artur Chilingarov, started from Chile on two Mi-8 helicopters and landed at the South Pole.[53][54]

On September 6, 2007, The National Geographic Channel's television show Man Made aired an episode on the construction of their new facility.[55]

On November 9, 2007, edition of NBC's Today, show co-anchor Ann Curry made a satellite telephone call which was broadcast live from the South Pole.[56]

On Christmas 2007, two employees at the base got into a fight and had to be evacuated.[57]

On July 11, 2011, the winter-over communications technician fell ill and was diagnosed with appendicitis. An emergency open appendectomy was performed by the station doctors with several winter-overs assisting during the surgery.

The 2011 BBC TV programme Frozen Planet discusses the base and shows footage of the inside and outside of the elevated station in the "Last Frontier Episode".

During the 2011 winter-over season, station manager Renee-Nicole Douceur experienced a stroke on August 27, resulting in loss of vision and cognitive function. Because the Amundsen–Scott base lacks diagnostic medical equipment such as an MRI or CT scan machine, station doctors were unable to fully evaluate the damage done by the stroke or the chance of recurrence. Physicians on site recommended a medevac flight as soon as possible for Douceur, but offsite doctors hired by Raytheon Polar Services (the company contracted to run the base) and the National Science Foundation disagreed with the severity of the situation. The National Science Foundation, which is the final authority on all flights and assumes all financial responsibility for the flights, denied the request for medevac, saying the weather was still too hazardous.[58] Plans were made to evacuate Douceur on the first flight available. Douceur and her niece, believing Douceur's condition to be grave and believing an earlier medevac flight possible, contacted Senator Jeanne Shaheen for assistance; as the NSF continued to state Douceur's condition did not qualify for a medevac attempt and conditions at the base would not permit an earlier flight, Douceur and her supporters brought the situation to media attention.[59][60] Douceur was evacuated, along with a doctor and an escort, on an October 17 cargo flight. This was the first flight available when the weather window opened up on October 16. This first flight is usually solely for supply and refueling of the station, and does not customarily accept passengers, as the plane's cabin is unpressurized.[61][62] The evacuation was successful, and Douceur arrived in Christchurch, New Zealand, at 10:55 p.m.[63] She ultimately made a full recovery.[64]

In March 2014, BICEP2 announced that they had detected B-modes from gravitational waves generated in the early universe, supporting the inflation theory of cosmology.[65] Later analysis showed that BICEP only saw polarized dust signal in the galaxy and not primordial B-modes.[66]

On 20 June 2016, there was another medical evacuation of two personnel around midwinter day, again involving Kenn Borek Air and DHC-6 Twin Otter aircraft.[67][68][69]

In December 2016, Buzz Aldrin was visiting the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station, Antarctica, as part of a tourist group, when he fell ill and was evacuated, first to McMurdo Station and from there to Christchurch, New Zealand, where he was reported to be in stable condition. Aldrin's visit at age 86 makes him the oldest person to ever reach the South Pole.

In the summer of 2016–17, Anthony Bourdain filmed part of an episode of his television show Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown at the station.[70]

In popular culture

[edit]

Science and life at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole station is documented in Dr. John Bird's award-winning book, One Day, One Night: Portraits of the South Pole[71][72][73][74] which chronicles the South Pole Foucault Pendulum,[75][76] the 300 Club,[74] the first midwinter medevac, and science at the Pole including climate change and cosmology.

Science fiction author Kim Stanley Robinson's book Antarctica features a fictionalized account of the culture at Amundsen–Scott and McMurdo, set in the near future.

The station is featured prominently in the 1998 The X-Files film Fight the Future.

The 2009 film Whiteout is mainly set at the Amundsen–Scott base, although the building layouts are completely different.

The turn-based strategy game Civilization VI, in its expansion Rise and Fall, included the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station as a Wonder.

The anime OVA Mobile Suit Gundam: The Origin features a large city in Antarctica called Scott City under a Geodesic dome not unlike the 1975 dome as the location of a major peace conference between the human space colonies controlled by Zeon and the Earth Federation.

The 2017 novel South Pole Station by Ashley Shelby is set at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole station of 2002-2003, prior to the opening of the new facility.

The 2019 film Where'd You Go, Bernadette features the station prominently and includes scenes of its construction at the closing credits, although the actual station depicted in the film is Halley VI British Antarctic Research Station.

Time zone

[edit]

The South Pole sees the Sun rise and set only once a year. Due to atmospheric refraction, these do not occur exactly on the September equinox and the March equinox, respectively: the Sun is above the horizon for four days longer at each equinox. The place has no solar time; there is no daily maximum or minimum solar height above the horizon. The station uses New Zealand time (UTC+12 during standard time and UTC+13 during daylight saving time) since all flights to McMurdo station depart from Christchurch and, therefore, all official travel from the pole goes through New Zealand.[77][78][79]

The zone identifier in the IANA time zone database was the deprecated Antarctica/South_Pole. It now uses the Pacific/Auckland timezone.

See also

[edit]- Concordia Station

- Kunlun Station

- List of Antarctic field camps

- List of Antarctic research stations

- Paul Siple

- Polheim, Amundsen's name for the first South Pole camp.

- Scott Base

- Vostok Station

References

[edit]- ^ a b Antarctic Station Catalogue (PDF) (catalogue). Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programs. August 2017. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-473-40409-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 22, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station". Geosciences: Polar Programs. National Science Foundation. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ "Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station Hydroponic Greenhouse". Giosciences: Polar Programs. National Science Foundation. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ Siple, Paul (1959). 90° South. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 158, 164, 168–169, 175–177, 192–193, 198, 239–240, 293, 303, 370–371.

- ^ "Edmund Hillary in Antarctica". New Zealand History. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- ^ Barna, Lynette; Courville, Zoe; Rand, John; Delaney, Allan (July 2015). Remediation of Old South Pole Station, Phase I: Ground-Penetrating-Radar Surveys. Hanover, NH: U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center. Archived from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- ^ "South Pole's first building blown up after 53 years". OurAmazingPlanet.com. March 31, 2011.

- ^ South Pole's First Building Blown Up After 53 Years, livescience.com, 2011

- ^ a b "Keck Array Overview". Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. National Science Foundation. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ "News about Antarctica - Deconstruction of the Dome (page 2)". The Antarctic Sun. United States Antarctic Program. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- ^ "News about Antarctica - Deconstruction of the Dome (page 1)". The Antarctic Sun. United States Antarctic Program. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- ^ "FY 2008 NSF Budget Request to Congress" (PDF). National Science Foundation. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ^ "A New Era". The Antarctic Sun. United States Antarctic Program. May 1, 2009. Retrieved May 1, 2009.

- ^ West, Peter. "National Science Foundation". National Science Foundation. Archived from the original on February 15, 2008. Retrieved September 12, 2021.

- ^ "Sub-Zero Tech". Modern Marvels. Season 12. Episode 11. February 23, 2005. History Channel.

- ^ "Initial Environmental Evaluation Development of Blue-Ice and Compacted-Snow Runways in support of the U.S. Antarctic Program". National Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs. April 9, 1993.

- ^ McLane, Marie (March 8, 2013). "South Pole enters winter with crew of 44 people". The Antarctic Sun. United States Antarctic Program. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ^ "South Pole - News". Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ^ Israel, D. J. (September 1, 2000). "South Pole TDRSS Relay (SPTR)". Astrophysics from Antarctica. 141: 319. Bibcode:1998ASPC..141..319I. Archived from the original on May 25, 2009. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ^ a b "CARA Science: Overview". University of Chicago Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ^ Coble, K.; Dragovan, M.; Kovac, J.; Halverson, N. W.; Holzapfel, W. L.; Knox, L.; Dodelson, S.; Ganga, K.; Alvarez, D.; Peterson, J. B.; Griffin, G.; Newcomb, M.; Miller, K.; Platt, S.R.; Novak, G. (July 1, 1999). "Anisotropy in the Cosmic Microwave Background at Degree Angular Scales: Python V Results". The Astrophysical Journal. 519 (1): L5 – L8. arXiv:astro-ph/9902195. Bibcode:1999ApJ...519L...5C. doi:10.1086/312093. S2CID 12276808.

- ^ "Arcminute Cosmology Bolometer Array Receiver: Instrument Description". Berkeley Cosmology Group. Archived from the original on January 10, 2014. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ^ Leitch, E.M.; et al. (December 2002). "Measurement of polarization with the Degree Angular Scale Interferometer". Nature. 420 (6917): 763–771. arXiv:astro-ph/0209476. Bibcode:2002Natur.420..763L. doi:10.1038/nature01271. PMID 12490940. S2CID 563348.

- ^ Ade, P.; Bock, J.; Bowden, M.; Brown, M. L.; Cahill, G.; Carlstrom, J. E.; Castro, P. G.; Church, S.; Culverhouse, T.; Friedman, R.; Ganga, K.; Gear, W. K.; Hinderks, J.; Kovac, J.; Lange, A. E.; Leitch, E.; Melhuish, S. J.; Murphy, J. A.; Orlando, A.; Schwarz, R.; O'Sullivan, C.; Piccirillo, L.; Pryke, C.; Rajguru, N.; Rusholme, B.; Taylor, A. N.; Thompson, K. L.; Wu, E. Y. S.; Zemcov, M. (February 10, 2008). "First Season QUaD CMB Temperature and Polarization Power Spectra". The Astrophysical Journal. 674 (1): 22–28. arXiv:0705.2359. Bibcode:2008ApJ...674...22A. doi:10.1086/524922. S2CID 14375472.

- ^ Brown, M. L.; Ade, P.; Bock, J.; Bowden, M.; Cahill, G.; Castro, P. G.; Church, S.; Culverhouse, T.; Friedman, R. B.; Ganga, K.; Gear, W. K.; Gupta, S.; Hinderks, J.; Kovac, J.; Lange, A. E.; Leitch, E.; Melhuish, S. J.; Memari, Y.; Murphy, J. A.; Orlando, A.; Sullivan, C. O'; Piccirillo, L.; Pryke, C.; Rajguru, N.; Rusholme, B.; Schwarz, R.; Taylor, A. N.; Thompson, K. L.; Turner, A. H.; Wu, E. Y. S.; Zemcov, M. (November 1, 2009). "Improved Measurements of the Temperature and Polarization of the Cosmic Microwave Background From QUaD". The Astrophysical Journal. 705 (1): 978–999. arXiv:0906.1003. Bibcode:2009ApJ...705..978B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/705/1/978. S2CID 1918381.

- ^ Francis, Matthew R. (May 16, 2016). "Dusting for the fingerprint of inflation with BICEP3". Symmetry. Fermilab/SLAC.

- ^ Ruhl, John; et al. (October 2004). "The South Pole Telescope". In Zmuidzinas, Jonas; Holland, Wayne S; Withington, Stafford (eds.). Millimeter and Submillimeter Detectors for Astronomy II. Vol. 5498. pp. 11–29. arXiv:astro-ph/0411122. doi:10.1117/12.552473. S2CID 17400060.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Mgrdichian, Laura. "Amanda's First Six Years". Phys.org. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ^ "IceCube South Pole Neutrino Observatory". University of Wisconsin-Madison. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ^ "South Pole, Antarctica". WeatherBase. Retrieved October 7, 2009.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

westarcticawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Weather and Climate – The Climate of Amundsen–Scott". Weather and Climate (Погода и климат) (in Russian). Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ^ Météo Climat (mean minimums, 1981-2010)"Météo Climat". Retrieved February 2, 2023.

- ^ Météo Climat (mean maximums, 1981-2010)"Météo Climat". Retrieved February 2, 2023.

- ^ "Klimatafel von Amundsen-Scott / Südpol-Station (USA) / Antarktis" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ^ "Amundsen–Scott Climate Normals 1961−1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ^ Palin, Michael. "Day 141: To the South Pole". palinstravels.co.uk. Archived from the original on October 2, 2022. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: BBC Worldwide (September 20, 2007). "Michael Palin reaches the South Pole". YouTube. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- ^ "Live From Antarctica". Passport to Knowledge. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- ^ Falxa, Greg. "Tech Crew at the South Pole Interactive TV Broadcast". Falxa.net. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ^ "In Memoriam". The CfA Almanac. XIII (2). Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. July 2000. Archived from the original on October 26, 2006. Retrieved December 19, 2006.

- ^ "Memorial". Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station. Retrieved December 19, 2006.

- ^ "Antarctic Researcher Dies" (Press release). Arlington, Virginia: National Science Foundation Office of Legislative and Public Affairs. May 12, 2000. Retrieved December 19, 2006.

- ^ "Australian scientist dies during Pole winter". The Antarctic Sun. United States Antarctic Program. October 22, 2000. Archived from the original on February 18, 2007. Retrieved December 19, 2006.

- ^ Chapman, Paul (December 14, 2006). "New Zealand Probes What May Be First South Pole Murder". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on November 3, 2007. Retrieved December 19, 2006.

- ^ "Death of Australian astrophysicist an Antarctic whodunnit". Deutsche Presse-Agentur. December 14, 2006. Archived from the original on September 1, 2007. Retrieved December 19, 2006.

- ^ Cockrell, Will (December 2009). "A Mysterious Death at the South Pole". Men's Journal. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ^ Weber, Bob (January 23, 2013). "Bad weather hampers search for 3 Canadians on plane missing in Antarctica". Global News. Archived from the original on February 19, 2013. Retrieved January 23, 2013.

- ^ "Kenn Borek plane carrying three Canadians missing in Antarctica". CTV News Calgary. January 23, 2013. Retrieved January 23, 2013.

- ^ Antol, Bob (April 2001). "The Rescue of Dr. Ron Shemenski from the South Pole". Bob Antol's Polar Journals. Retrieved January 23, 2013.

- ^ "Doctor rescued from Antarctica safely in Chile". The New Zealand Herald. April 27, 2001. Retrieved January 23, 2013.

- ^ "Plane With Dr. Shemenski Arrives in Chile". CNN. April 26, 2001. Retrieved January 23, 2013.

- ^ "Patrushev lands at South Pole during Antarctic expedition". Interfax. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007.

- ^ "Two Russian helicopters land at the South Pole". TimesRussia. January 9, 2007. Archived from the original on October 9, 2007. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ^ "Man-Made: The South Pole Project". National Geographic Channel. Archived from the original on October 22, 2007.

- ^ Celizic, Mike (November 9, 2007). "Today's world traveler ready to come back". Today.com. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ^ McMahon, Barbara (December 27, 2007). "Antarctic base staff evacuated after Christmas brawl". The Guardian. London. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ^ "Pilot describes Antarctica wx challenges". Weather.com. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011.

- ^ Quenqua, Douglas (October 7, 2011). "Worker at South Pole Station Pushes for a Rescue After a Stroke". The New York Times. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ Niiler, Eric (October 7, 2011). "Evacuation is denied for South Pole stroke victim". MSNBC. Archived from the original on October 8, 2011. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ "Raytheon worker stuck in South Pole is coming home". Boston Herald. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ Potter, Ned (October 11, 2011). "South Pole: Stroke Victim Waits for Plane Flight". ABC News. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ "Sick American engineer flies out of South Pole". MSNBC. October 17, 2011. Archived from the original on October 17, 2011. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

- ^ Walker, Andrea K. (October 28, 2011). "South Pole stroke victim recovering at Johns Hopkins". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (March 17, 2014). "Detection of Waves in Space Buttresses Landmark Theory of Big Bang". The New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

- ^ Scoles, Sarah (October 28, 2015). "The Nature of Reality: The B-Mode Story You Haven't Heard". PBS. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- ^ "Antarctic medical evacuation planes reach British station at Rothera" (Press release). Arlington, Virginia: National Science Foundation. June 20, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ "News". South Pole News. July 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ Ramzy, Austin (June 22, 2016). "Rescue Flight Lands at South Pole to Evacuate Sick Worker". The New York Times. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ^ West, Adam (February 23, 2017). "Summer's Almost Gone". The Antarctic Sun. United States Antarctic Program. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ^ Bird, John; McCallum, Jennifer (2017). One Day, One Night: Portraits of the South Pole. Createspace. ISBN 978-1539947301.

- ^ "2016 NEW YORK BOOK FESTIVAL WINNERS". Archived from the original on January 31, 2022. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- ^ "Winners and Finalists 2017". Next Generation Indie Book Awards. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- ^ a b Hughes, Becky (January 24, 2018). "Explore Life at the South Pole in One Day, One Night: Portraits of the South Pole". Parade. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- ^ Johnson, George (September 24, 2002). "Here They Are, Science's 10 Most Beautiful Experiments". The New York Times. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- ^ Baker, G. P. (2011). Seven Tales of the Pendulum. Oxford University Press. p. 388. ISBN 978-0-19-958951-7.

- ^ "What time zone is used in Antarctica?". Antarctica.uk. January 14, 2023. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- ^ "Time Zones Currently Being Used in Antarctica". Time and Date AS. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- ^ Dempsey, Caitlin (March 29, 2023). "Which Country Has the Most Time Zones?". Geography Realm. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

External links

[edit]- "South Pole Station images and maps". old and, well, older looks at Old Pole.

- "South Pole Station Webcams". United States Antarctic Program.

- "Amundsen–Scott Station webcam". NOAA.

- "Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station". National Science Foundation.

- "Antarctic Facilities". COMNAP. Archived from the original on April 24, 2008.

- "Antarctic Facilities Map (Edition 5)" (PDF). COMNAP. July 24, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 20, 2011.

- Spindler, Bill. "Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station". southpolestation.com.

- "Iceman's South Pole page". antarctic-adventures.de.

- "Weak Nuclear Force". Wordpress.

- Current weather for NZSP at NOAA/NWS