The Fox and the Hound

| The Fox and the Hound | |

|---|---|

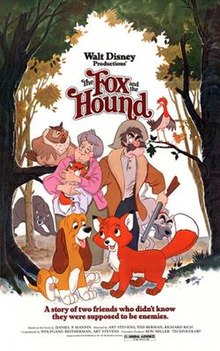

Original theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | |

| Story by |

|

| Based on | The Fox and the Hound by Daniel P. Mannix |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Edited by | James Melton Jim Koford |

| Music by | Buddy Baker |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Distribution |

Release date |

|

Running time | 83 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $12 million[1] |

| Box office | $63.5 million[2] |

The Fox and the Hound is a 1981 American animated buddy drama film produced by Walt Disney Productions and loosely based on the 1967 novel of the same name by Daniel P. Mannix. It tells the story of the unlikely friendship between a red fox named Tod and a hound named Copper, as they struggle against their emerging instincts and the realization that they are meant to be adversaries.

The film was directed by Ted Berman, Richard Rich, and Art Stevens. It was produced by Ron Miller, Wolfgang Reitherman, and Art Stevens. The ensemble voice cast consists of Mickey Rooney as Tod and Kurt Russell as Copper, respectively, with Pearl Bailey, Jack Albertson, Sandy Duncan, Jeanette Nolan, Pat Buttram, John Fiedler, John McIntire, Dick Bakalyan, Paul Winchell, Keith Mitchell, and Corey Feldman providing the voices of the other characters of the film. Mitchell and Feldman in particular voiced Young Tod and Young Copper. The instrumental musical score to the film was composed and conducted by Buddy Baker, with Walter Sheets performing the orchestration.

Walt Disney Productions first obtained the film rights to the novel by Daniel P. Mannix in 1967; however, actual development on the film would not occur until spring 1977. It marked the last involvement of the remaining members of Disney's Nine Old Men, which included Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston. Though they had involvement in early development of the film, it was ultimately handed over to a new generation of animators following the retirement of the old animators. As such, it was the first film for future directors, including Tim Burton, Brad Bird, and John Lasseter. During production, its release was delayed by over six months following the abrupt departure of Don Bluth and his team of animators. Further concerns were raised over the handling of the scene in which Chief is hit by a train, which was originally planned to result in him dying. After debating the handling of the scene, the filmmakers decided to change the death into a non-fatal injury by which he merely suffers a broken leg.

The film was released to theaters on July 10, 1981, by Buena Vista Distribution. It was a financial success, earning $39.9 million domestically and receiving mixed reviews from critics. It was nominated for three awards, of which it won one. At the time of its release, it was the most expensive animated film produced to date, costing $12 million.[1] It was re-released to theaters on March 25, 1988.[3] An intermediate follow-up, The Fox and the Hound 2, was released directly-to-DVD on December 12, 2006.

Plot

After a young red fox is orphaned, Big Mama the owl and her friends, Dinky the finch and Boomer the woodpecker, arrange for him to be adopted by a kindly farmer named Widow Tweed, who names him Tod. Meanwhile, her neighbor, hunter Amos Slade, brings home a young hound puppy named Copper and introduces him to his hunting dog, Chief, who is at first annoyed by him but then learns to love him. One day, Tod and Copper meet and become best friends, pledging eternal friendship. Amos grows frustrated at Copper for constantly wandering off to play and places him on a leash. While playing with Copper outside his barrel, Tod accidentally awakens Chief. Amos and Chief chase him until they are stopped by Tweed. After an argument, Amos threatens to kill Tod if he trespasses on his property again. Hunting season comes, and Amos takes Chief and Copper into the wilderness for the interim. Meanwhile, Big Mama, Dinky, and Boomer attempt to explain to Tod that Copper will soon become his enemy. However, he naively insists that they will remain friends forever.

The following spring, Tod and Copper reach adulthood. Copper returns as an expert hunting dog who is expected to track down foxes. Late at night, Tod sneaks over to visit him. Their conversation awakens Chief, who alerts Amos. A chase ensues, and Copper catches Tod but lets him go while diverting Amos. Chief catches Tod as he attempts an escape on a railroad track, but an oncoming train strikes him, resulting in him falling into the river below and breaking his leg. Enraged by this, Copper and Amos blame Tod for the accident and vow vengeance. Realizing Tod is no longer safe with her, Tweed leaves him at a game reserve. After a disastrous night on his own in the woods, Big Mama introduces him to Vixey, a female fox who helps him adapt to life there.

Amos and Copper trespass into the reserve and hunt Tod and Vixey. The chase climaxes when they inadvertently provoke an attack from a giant bear. Amos trips and falls into one of his own traps, dropping his rifle slightly out of reach. Copper violently fights the bear, but is almost killed by it. Tod comes to his rescue and battles it until they both fall down a waterfall. As Copper approaches Tod as he lies wounded in the lake below, Amos appears, ready to shoot him. Copper positions himself in front of him to prevent Amos from doing so, refusing to move away. Amos, understanding Tod had saved their lives from the bear, decides to spare Tod for Copper, lowers his rifle, and leaves with Copper. Tod and Copper share one last smile before parting.

At home, Tweed nurses Amos back to health, much to his humiliation. As he lies down to take a nap, Copper smiles as he remembers the day when he first met Tod. At the same moment, Vixey joins Tod on top of a hill as they both look down on Amos' and Tweed's homes.

Voice cast

- Mickey Rooney as Tod

- Keith Mitchell as Young Tod

- Kurt Russell as Copper

- Corey Feldman as Young Copper

- Pearl Bailey as Big Mama

- Jack Albertson as Amos Slade

- Sandy Duncan as Vixey

- Jeanette Nolan as Widow Tweed

- Pat Buttram as Chief

- John Fiedler as The Porcupine

- John McIntire as The Badger

- Dick Bakalyan as Dinky

- Paul Winchell as Boomer

- "Squeaks the Caterpillar" is listed as playing "himself"

Production

Development

In May 1967, shortly before the novel won the Dutton Animal Book Award, it was reported that Walt Disney Productions had obtained the film rights to it.[4] In spring 1977, development began on the project after Wolfgang Reitherman had read the original novel and decided that it would make for a good animated feature as one of his sons had once owned a pet fox years before.[3][5] The title was initially reported as The Fox and the Hounds,[6] but the filmmakers dropped the plural as the story began to focus more and more on the two leads.[7] Reitherman was the film's original director, along with Art Stevens as codirector. A power struggle between the two directors and coproducer Ron Miller broke out over key sections of the film, with Miller supporting the younger Stevens. Miller instructed Reitherman to surrender reins over to the junior personnel,[8] but Reitherman resisted due to a lack of trust in the young animators.[9]

In an earlier version of the film, Chief was slated to die as he did in the novel. However, the scene was modified to have him survive with a broken leg. Animator Ron Clements, who had briefly transitioned into the story department, protested, "Chief has to die. The picture doesn't work if he just breaks his leg. Copper doesn't have motivation to hate the fox."[10] Likewise, younger members of the story team pleaded with Stevens to have him killed. He countered, "Geez, we never killed a main character in a Disney film and we're not starting now!" The younger crew members took the problem to upper management, who would also back Stevens.[10] Ollie Johnston's test animation of Chief stomping around the house with his leg in a cast was eventually kept, and Randy Cartwright reanimated the scene where Copper finds his body and had him animate his eyes opening and closing so the audience knew that he was not dead.[11]

Another fight erupted when Reitherman, in thinking the film lacked a strong second act, decided to add a musical sequence of two swooping cranes voiced by Phil Harris and Charo. These characters would sing a silly song titled "Scoobie-Doobie Doobie Doo, Let Your Body Turn to Goo" to Tod after he was dropped in the forest. Charo had recorded the song and several voice tracks which were storyboarded,[12] and live-action reference footage was shot of her wearing a sweaty pink leotard. However, the scene was strongly disliked by studio personnel who felt the song was a distraction from the main plot, with Stevens stating, "We can't let that sequence in the movie! It's totally out of place!"[13] He notified studio management, and after many story conferences, the scene was removed. Reitherman later walked into his office, slumped in a chair, and said, "I dunno, Art, maybe this is a young man's medium." He later moved on to undeveloped projects such as Catfish Bend.[14]

Animation

By late 1978, Frank Thomas, Ollie Johnston, and Cliff Nordberg had completed their animation. Thomas had animated scenes of Tod and Copper using dialogue Larry Clemmons had written and recorded with the child actors.[15] The film would mark the last one to have the involvement of Disney's Nine Old Men, who had retired early during production,[16] and animation was turned over to the next generation of directors and animators, which included John Lasseter, John Musker, Ron Clements, Glen Keane, Tim Burton, Brad Bird, Henry Selick, Chris Buck, Mike Gabriel, and Mark Dindal, all of whom would finalize the animation and complete the film's production. These animators had moved through the in-house animation training program and would play an important role in the Disney Renaissance of the 1980s and 1990s.[17]

However, the transition between the old guard and the new resulted in arguments over how to handle the film. Reitherman had his own ideas on the designs and layouts that should be used, but the newer team backed Stevens. Animator Don Bluth animated several scenes, including of Widow Tweed milking her cow, Abigail, while his team worked on the rest of the sequence, and when she fires at Amos' automobile. Nevertheless, Bluth and the new animators felt that Reitherman was too stern and out of touch,[12] and on his 42nd birthday, September 13, 1979, Bluth, along with Gary Goldman and John Pomeroy, entered Ron Miller's office, and they turned in their resignations. Soon after, 13 more animators followed suit in turning in their resignations. Though Bluth and his team had animated substantial scenes, they asked not to receive screen credit.[16]

With those animators now gone,[3] Miller ordered all of the resigning animators off the studio lot by noon of that same day and would later push the film's release from Christmas 1980 to summer 1981. New animators were hired and promoted to fill the ranks. To compensate for the lack of experience of the new animators, much of the quality control would rely upon a network of veteran assistant animators.[18][11] Four years after production started, the film was finished with approximately 360,000 drawings, 110,000 painted cels, and 1,100 painted backgrounds making up the finished product. A total of 180 people, including 24 animators, worked on the film.[3]

Casting

Early into production, the principal characters such as Young Tod, Young Copper, Big Mama, and Amos Slade had already been cast. The supporting roles were filled by Disney voice regulars including Pat Buttram as Chief, Paul Winchell as Boomer, and Mickey Rooney, who had just finished filming Pete's Dragon (1977), as Adult Tod. Jeanette Nolan was the second choice for Widow Tweed after Helen Hayes turned down the role.[19] The last role to be cast was Adult Copper. Jackie Cooper had auditioned for the role but left the project when he demanded more money than the studio was willing to pay. While filming the Elvis (1979) television film, former Disney young actor Kurt Russell was cast following a reading that had impressed the filmmakers and completed his dialogue in two recording sessions.[20] The growling vocals for the bear were provided by sound effects artist Jimmy MacDonald.[21]

Soundtrack

| The Fox and the Hound | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Various artists | ||||

| Released | 1981 | |||

| Recorded | 1977–1981 | |||

| Genre | Children's, classical | |||

| Label | Walt Disney | |||

| Walt Disney Animation Studios soundtrack chronology | ||||

| ||||

The soundtrack album for the film was released in 1981 by Disneyland Records.[22] It contains songs written by Stan Fidel, Jim Stafford, and Jeffrey Patch.[23]

Track listing

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Performer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Best of Friends" | Stan Fidel | Pearl Bailey | |

| 2. | "Lack of Education" | Jim Stafford | Pearl Bailey | |

| 3. | "A Huntin' Man" | Jim Stafford | Jack Albertson | |

| 4. | "Appreciate the Lady" | Jim Stafford | Pearl Bailey | |

| 5. | "Goodbye May Seem Forever" | Jeffrey Patch | Jeanette Nolan & Chorus |

Release

Box office

In its original release, the film grossed $39.9 million in domestic grosses, the highest for an animated film at the time from its initial release.[24] Its distributor rentals were reported to be $14.2 million, while its international rentals totaled $43 million.[25] It was rereleased theatrically on March 25, 1988,[3] where it grossed $23.5 million.[26] It has had a lifetime gross of $63.5 million across its original release and reissue.[2]

Home media

The film was first released on VHS on March 4, 1994, as the last entry in the Walt Disney Classics line. This release was placed into moratorium on April 30, 1995.[27] On May 2, 2000, it was released on Region 1 DVD for the first time as part of the Walt Disney Gold Classic Collection line, along with a simultaneous VHS re-issue as part of the same video line on the same day.[28][29] This edition went into moratorium in January 2006.[30] Soon after, a 25th anniversary special edition DVD was released on October 10, 2006.[31]

The film was released on Blu-ray on August 9, 2011, commemorating its 30th anniversary as part of a 3-disc Blu-ray/DVD combo pack that was bundled as a 2-movie Collection Edition featuring The Fox and the Hound 2 on the same Blu-ray Disc, as well as separate DVD versions of both films. Featuring a new digital restoration, the Blu-ray transfer presents the film for the first time in 1.66:1 widescreen and also features 5.1 DTS-HD Master Audio. The Fox and the Hound 2 is presented in 1.78:1 widescreen and features the same audio channel as the first film.[32] A DVD-only edition of the 2-movie Collection, again featuring both films on separate discs, was also released on the same day.[32]

Critical reception

Initial reviews

Vincent Canby of The New York Times claimed that the film "breaks no new ground whatsoever", while describing it as "a pretty, relentlessly cheery, old-fashioned sort of Disney cartoon feature, chock-full of bouncy songs of an upbeatness that is stickier than Krazy Glue and played by animals more anthropomorphic than the humans that occasionally appear." He further commented that the film "is rather overstuffed with whimsy and folksy dialogue. It also possesses a climax that could very well scare the daylights out of the smaller tykes in the audience, though all ends well. Parents who don't relish chaperoning their tykes to see the movie, but find they must anyway, can take heart in the knowledge that the running time is 83 minutes. That's about as short as you can get these days."[33] Sheila Benson of the Los Angeles Times praised the animation but criticized the story for playing it too safe. She acknowledged that the writers were "protecting us from important stuff: from rage, from pain, from loss. By these lies, done for our own good, of course, they also limit the growth that is possible."[34] David Ansen of Newsweek stated, "Adults may wince at some of the sticky-sweet songs, but the movie is not intended for grownups."[1]

Richard Corliss of Time magazine praised the film for its intelligent story about prejudice. He argued that it shows that biased attitudes can poison even the deepest relationships, and its bittersweet ending delivers a powerful and important moral message to audiences.[35] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times also praised it, saying, "For all of its familiar qualities, this movie marks something of a departure for the Disney studio, and its movement is in an interesting direction. The Fox and the Hound is one of those relatively rare Disney animated features that contains a useful lesson for its younger audiences. It's not just cute animals and frightening adventures and a happy ending; it's also a rather thoughtful meditation on how society determines our behavior."[36]

Retrospective reviews

TV Guide gave the film four out of five stars, saying, "The animation here is better than average (veteran Disney animators Wolfgang Reitherman and Art Stevens supervised the talents of a new crop of artists that developed during a 10-year program at the studio), though not quite up to the quality of Disney Studios in its heyday. Still, this film has a lot of 'heart' and is wonderful entertainment for both kids and their parents. Listen for a number of favorites among the voices."[37] Michael Scheinfeld of Common Sense Media gave its quality a rating of 4 out of 5 stars, stating, "It develops into a thoughtful examination of friendship and includes some mature themes, especially loss."[38]

In The Animated Movie Guide, Jerry Beck considered the film "average", though he praises the voice work of Pearl Bailey as Big Mama and the extreme dedication to detail shown by animator Glen Keane in crafting the fight scene between Copper, Tod, and the bear.[39] In his book The Disney Films, Leonard Maltin also notes that that scene received great praise in the animation world. However, he felt the film relied too much on "formula cuteness, formula comedy relief, and even formula characterizations".[40] Overall, he considered it "charming" stating that it is "warm, and brimming with personable characters" and that it "approaches the old Disney magic at times."[41] Craig Butler from All Movie Guide stated that it was a "warm and amusing, if slightly dull, entry in the Disney animated canon." He also called it "conventional and generally predictable" with problems in pacing. However, he praised its climax and animation, as well as the ending. His final remark is that "Two of the directors, Richard Rich and Ted Berman, would next direct The Black Cauldron, a less successful but more ambitious project."[42]

Rob Humanick of Slant Magazine gave the film 31⁄2 out of five stars, noting that it was the transition point between the remaining original animators since Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to the new generation, saying that "the results culled the best qualities of both groups." and that "The result is a work of both learned, assured poise and triumphant freshman determination, not far away (in style or quality) from other benchmark-status works, like the aforementioned Snow White or Pixar’s Toy Story."[43] RL Shaffer of IGN wrote a rather mixed review, claiming that it "is just not as impressive as Disney's early work, or their late '80s/early '90s pictures."[44] James Kendrick of Q Network Film Desk stated that it "is not one of the studio's best efforts, but nonetheless it remains a fascinating product of an era of upheaval as well as a meaningful statement about the nature of prejudice."[45] Peter Canavense of Groucho Reviews stated that it "is sweet but a bit dull", noting that "Overall, the picture is good-hearted and colorful, with an ending that carries a nice touch of ambiguity about the tussle of nature and nurture."[46] John J. Puccio of Movie Metropolis claimed that it "is very sweet and no doubt a delight for children, but I found it quite slow and tedious."[47]

The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reported that the film received a 75% approval rating with an average rating of 6.5/10 based on 28 reviews. The website's consensus states that "The Fox and the Hound is a likeable, charming, unassuming effort that manages to transcend its thin, predictable plot."[48] Metacritic gave it a score of 65 based on 15 reviews, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[49]

Accolades

The film was awarded a Golden Screen Award (German: Goldene Leinwand) in 1982. In the same year, it was also nominated for a Young Artist Award and the Saturn Award for Best Fantasy Film.[50]

| Year | Ceremony | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1982 | 9th Saturn Awards[51] | Best Fantasy Film | Nominated |

| 1982 Golden Screen Awards[50] | Won | ||

| 5th Youth in Film Awards[50][52] | Best Motion Picture - Fantasy or Comedy - Family Enjoyment | Nominated |

Related media

Comic adaptations

As well as adaptations of the film itself, comic strips featuring the characters also appeared in stories unconnected to it. Examples include The Lost Fawn, in which Copper uses his sense of smell to help Tod find a fawn who has gone astray;[53] The Escape, in which Tod and Vixey must save a Canadian goose from a bobcat;[54] The Chase, in which Copper must safeguard a sleepwalking Chief;[55] and Feathered Friends, in which Dinky and Boomer must go to desperate lengths to save one of Widow Tweed's chickens from a coyote.[56]

A comic adaptation of the film, drawn by Richard Moore, was published in newspapers as part of Disney's Treasury of Classic Tales.[57] A comic-book titled The Fox and the Hound followed, with new adventures of the characters. From 1981 to 2007, a few Fox and the Hound Disney comics stories were produced in Italy, Netherlands, Brazil, France, and the United States.[58]

Sequel

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2022) |

An intermediate follow-up, The Fox and the Hound 2, was released directly-to-DVD on December 12, 2006.[59] It takes place during Tod and Copper's youth, before the events of the later half of the first film. The storyline involves Copper being tempted to join a band of singing stray dogs called "The Singin' Strays", thus threatening his friendship with Tod. It was critically panned, with critics calling it a pale imitation of its predecessor.

See also

- Foxes in popular culture, films and literature

- The Belstone Fox, a 1973 British film with similar themes, based on David Rook's 1970 novel, The Ballad of the Belstone Fox

References

- ^ a b c Ansen, David (July 13, 1981). "Forest Friendship". Newsweek. p. 81.

- ^ a b "The Fox and the Hound (1981)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e "Fox and the Hound, The (film)". D23. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- ^ "Dutton Animal Award Goes To Mannix Book Set for Fall". The New York Times. May 20, 1967. p. 33. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ^ Grant, John (1998). The Encyclopedia of Walt Disney's Animated Characters: From Mickey Mouse to Hercules. Disney Editions. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-786-86336-5.

- ^ "A new generation of animators is taking over at Disney studios". The Baltimore Sun. July 19, 1977. p. B4. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved July 31, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Koenig 1997, p. 167.

- ^ Hulett 2014, p. 33.

- ^ Beck 2005, p. 86.

- ^ a b Hulett 2014, p. 39.

- ^ a b Sito, Tom (November 1998). "Disney's The Fox and the Hound: The Coming of the Next Generation". Animation World Magazine. Archived from the original on June 4, 2016. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- ^ a b Koenig 1997, p. 168.

- ^ Hulett 2014, p. 34.

- ^ Sito 2006, p. 289.

- ^ Sito 2006, p. 298.

- ^ a b Cawley, John. "Don Bluth The Disney Years: Fox and Hound". Cataroo. Archived from the original on August 3, 2016. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- ^ Finch, Christopher (1973). "The End of an Era". The Art of Walt Disney: From Mickey Mouse to the Magic Kingdom (2004 ed.). Harry N. Abrams. pp. 260–266. ISBN 978-0-810-99814-8.

- ^ Sito 2006, p. 290.

- ^ Hulett 2014, p. 35.

- ^ Hulett 2014, p. 37.

- ^ Kernan, Michael (April 24, 1982). "The Squeak That Roared". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 21, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ "The Fox and the Hound - Soundtrack Details". SoundtrackCollector.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ^ "Various - The Fox and the Hound (Vinyl, LP)". Discogs. 1981. Archived from the original on March 26, 2015. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ^ Eller, Claudia (January 9, 1990). "'Mermaid' Swims to Animation Record". Daily Variety. p. 1.

- ^ Thomas, Bob (September 19, 1984). "Walt Disney Productions returns to animation". Lewison Daily Sun. Sun Media Group. Archived from the original on December 31, 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2016 – via Google News Archive.

- ^ "The Fox and the Hound (reissue) (1988)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- ^ Liebenson, Donald (February 19, 1995). "How to Outsmart Disney's Moratorium". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- ^ "The Fox and the Hound: Gold Collection DVD Review". DVDDizzy. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

- ^ Liebenson, Donald (May 4, 2000). "Good Neighbor Disney". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 11, 2022. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ "Out of Print Disney DVDs – The Ultimate Guide to Disney DVD". DVDDizzy. 6 February 2012. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ "The Fox and the Hound 25th Anniversary Edition DVD Review". DVDDizzy. Archived from the original on March 26, 2012. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

- ^ a b "The Fox and the Hound and The Fox and the Hound 2: 2 Movie Collection Blu-ray + DVD Review". DVDDizzy. Archived from the original on May 31, 2012. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (July 10, 1981). "Film: Old-Style Disney". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 13, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ Benson, Sheila (July 10, 1981). "'Fox, Hound' Cuts No Corners". Los Angeles Times. Part VI, pp. 1, 5. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (July 20, 1981). "Cinema: The New Generation Comes of Age". Time. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 10, 1981). "The Fox and the Hound Movie Review (1981)". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on March 20, 2016. Retrieved May 4, 2016 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ "The Fox And The Hound: Review". TV Guide. CBS Interactive. Retrieved August 7, 2015.

- ^ Michael Scheinfeld (June 15, 2010). "The Fox and the Hound Movie Review". Common Sense Media. Retrieved August 10, 2016.

- ^ Beck 2005, p. 87.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (2000). "Chapter 3: Without Walt". The Disney Films. Disney Editions. p. 275. ISBN 978-0786885275.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (2010). Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide. New York: Signet. p. 490. ISBN 978-0-451-22764-5.

- ^ "The Fox and the Hound (1981)". AllMovie. Retrieved August 7, 2015.

- ^ Humanick, Rob (August 10, 2011). "Review: The Fox and the Hound and The Fox and the Hound 2 on Disney Blu-ray". Slant Magazine. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ RL Shaffer (August 18, 2011). "The Fox and the Hound / The Fox and the Hound II Blu-ray Review". IGN. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ James Kendrick. "The Fox and the Hound". Q Network. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ Canavese, Peter. "The Fox and the Hound/The Fox and the Hound II (1981) [***]". GrouchoReviews. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ J. Puccio, John (October 11, 2006). "FOX AND THE HOUND, THE - DVD review". Movie Metropolis. Archived from the original on October 27, 2014. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ "The Fox and the Hound". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on January 4, 2022. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ "The Fox and the Hound Reviews". Metacritic. Red Ventures. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022.

- ^ a b c "The Fox and the Hound – Awards". IMDb. Archived from the original on August 30, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ^ "Past Saturn Awards". Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films. Archived from the original on December 19, 2008. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ^ "5th Annual Awards". Young Artist Association. Archived from the original on April 3, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ^ "The Lost Fawn". Inducks. October 10, 1981. Archived from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2012.

- ^ "The Escape". Inducks. October 10, 1981. Archived from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2012.

- ^ "The Chase". Inducks. October 10, 1981. Archived from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2012.

- ^ "Feathered Friends". Inducks. October 10, 1981. Archived from the original on June 29, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2012.

- ^ A. Becattini; L. Boschi (1984). "La produzione sindacata". p. 55.

- ^ "List of 'The Fox and the Hound' Comics on Inducks". Inducks. October 10, 1981. Archived from the original on June 29, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2012.

- ^ "The Fox and the Hound 2 (2006)". BFI. Archived from the original on May 27, 2016. Retrieved 2022-12-20.

Bibliography

- Beck, Jerry (2005). The Animated Movie Guide. Chicago Reader Press. ISBN 978-1-556-52591-9.

- Hulett, Steve (2014). Mouse In Transition: An Insider's Look at Disney Feature Animation. Theme Park Press. ISBN 978-1-941-50024-8.

- Koenig, David (1997). Mouse Under Glass: Secrets of Disney Animation & Theme Parks. Bonaventure Press. ISBN 978-0-964-06051-7.

- Sito, Tom (2006). Drawing the Line: The Untold Story of the Animation Unions from Bosko to Bart Simpson. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-813-12407-0.

External links

- 1981 films

- 1981 American animated films

- 1980s buddy drama films

- 1980s children's animated films

- 1980s coming-of-age drama films

- 1980s English-language films

- 1981 children's films

- 1981 directorial debut films

- 1981 drama films

- American buddy drama films

- American children's animated drama films

- American coming-of-age drama films

- Animated buddy films

- Animated coming-of-age films

- Animated films about dogs

- Animated films about foxes

- Animated films about orphans

- Animated films about prejudice

- Animated films about friendship

- Animated films about talking animals

- Animated films about trains

- Animated films based on American novels

- Animated films set in North America

- Animated films set on farms

- Films adapted into comics

- Films directed by Art Stevens

- Films directed by Richard Rich (filmmaker)

- Films directed by Ted Berman

- Films produced by Ron W. Miller

- Films scored by Buddy Baker (composer)

- Films with screenplays by Burny Mattinson

- Films with screenplays by Larry Clemmons

- Films with screenplays by Vance Gerry

- Walt Disney Animation Studios films

- English-language buddy drama films

- Films with screenplays by Ted Berman

- Films with screenplays by David Michener

- Films with screenplays by Peter Young

- Films with screenplays by Steve Hulett

- Films with screenplays by Earl Kress