Amnesty International

| |

| Founded | July 1961 United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Founders | |

| Type | |

| Headquarters | London, WC1 United Kingdom |

| Location |

|

| Services | Protecting human rights |

| Fields | Media attention, direct-appeal campaigns, research, lobbying |

| Members | More than ten million members and supporters[1] |

| Agnès Callamard[2] | |

| Website | amnesty.org |

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says it has more than ten million members and supporters around the world.[1] The stated mission of the organization is to campaign for "a world in which every person enjoys all of the human rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments."[3] The organization has played a notable role on human rights issues due to its frequent citation in media and by world leaders.[4][5]

AI was founded in London in 1961 by the lawyer Peter Benenson.[6] In what he called "The Forgotten Prisoners" and "An Appeal for Amnesty", which appeared on the front page of the British newspaper The Observer, Benenson wrote about two students who toasted to freedom in Portugal and four other people who had been jailed in other nations because of their beliefs. AI's original focus was prisoners of conscience, with its remit widening in the 1970s, under the leadership of Seán MacBride and Martin Ennals, to include miscarriages of justice and torture. In 1977, it was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. In the 1980s, its secretary general was Thomas Hammarberg, succeeded in the 1990s by Pierre Sané. In the 2000s, it was led by Irene Khan.

Amnesty draws attention to human rights abuses and campaigns for compliance with international laws and standards. It works to mobilize public opinion to generate pressure on governments where abuse takes place.[7]

History

1960s

Amnesty International was founded in London in July 1961 by English barrister Peter Benenson, who had previously been a founding member of the UK law reform organization JUSTICE.[8] Benenson was influenced by his friend Louis Blom-Cooper, who led a political prisoners' campaign.[9][10] According to Benenson's own account, he was travelling on the London Underground on 19 November 1960 when he read that two Portuguese students from Coimbra had been sentenced to seven years of imprisonment in Portugal for allegedly "having drunk a toast to liberty".[a][11] Researchers have never traced the alleged newspaper article in question.[a] In 1960, Portugal was ruled by the Estado Novo government of António de Oliveira Salazar.[12] The government was authoritarian in nature and strongly anti-communist, suppressing enemies of the state as anti-Portuguese. In his significant newspaper article "The Forgotten Prisoners", Benenson later described his reaction as follows:

Open your newspaper any day of the week and you will find a story from somewhere of someone being imprisoned, tortured or executed because his opinions or religion are unacceptable to his government... The newspaper reader feels a sickening sense of impotence. Yet if these feelings of disgust could be united into common action, something effective could be done.[6]

Benenson worked with his friend Eric Baker – a member of the Religious Society of Friends who had been involved in funding the British Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament as well as becoming head of Quaker Peace and Social Witness. In his memoirs, Benenson described him as "a partner in the launching of the project".[13] In consultation with other writers, academics and lawyers and, in particular, Alec Digges, they wrote via Louis Blom-Cooper to David Astor, editor of The Observer newspaper, who, on 28 May 1961, published Benenson's article "The Forgotten Prisoners". The article brought the reader's attention to those "imprisoned, tortured or executed because his opinions or religion are unacceptable to his government"[6] or, put another way, to violations, by governments, of articles 18 and 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). The article described these violations occurring, on a global scale, in the context of restrictions to press freedom, to political oppositions, to timely public trial before impartial courts, and to asylum. It marked the launch of "Appeal for Amnesty, 1961", the aim of which was to mobilize public opinion, quickly and widely, in defence of these individuals, whom Benenson named "Prisoners of Conscience".[14]

The "Appeal for Amnesty" was reprinted by a large number of international newspapers. In the same year, Benenson had a book published, Persecution 1961, which detailed the cases of nine prisoners of conscience investigated and compiled by Benenson and Baker (Maurice Audin, Ashton Jones, Agostinho Neto, Patrick Duncan, Olga Ivinskaya, Luis Taruc, Constantin Noica, Antonio Amat and Hu Feng).[14]

In July 1961, the leadership had decided that the appeal would form the basis of a permanent organization, Amnesty, with the first meeting taking place in London. Benenson ensured that all three major political parties were represented, enlisting members of parliament from the Labour Party, the Conservative Party, and the Liberal Party.[15] On 30 September 1962, it was officially named "Amnesty International". Between the "Appeal for Amnesty, 1961" and September 1962 the organization had been known simply as "Amnesty".[16]

By the mid-1960s, Amnesty International's global presence was growing and an International Secretariat and International Executive Committee were established to manage Amnesty International's national organizations, called "Sections", which had appeared in several countries. They were secretly supported by the British government at the time.[17] The international movement was starting to agree on its core principles and techniques. For example, the issue of whether or not to adopt prisoners who had advocated violence, like Nelson Mandela, brought unanimous agreement that it could not give the name of "Prisoner of Conscience" to such prisoners. Aside from the work of the library and groups, Amnesty International's activities were expanding to helping prisoners' families, sending observers to trials, making representations to governments, and finding asylum or overseas employment for prisoners. Its activity and influence were also increasing within intergovernmental organizations; it would be awarded consultative status by the United Nations, the Council of Europe and UNESCO before the decade ended.[18]

In 1966, Benenson suspected that the British government in collusion with some Amnesty employees had suppressed a report on British atrocities in Aden.[19] He began to suspect that many of his colleagues were part of a British intelligence conspiracy to subvert Amnesty, but he could not convince anybody else at AI.[20] Later in the same year, there were further allegations, when the US government reported that Seán MacBride, the former Irish foreign minister and Amnesty's first chairman, had been involved with a Central Intelligence Agency funding operation.[19] MacBride denied knowledge of the funding, but Benenson became convinced that MacBride was a member of a CIA network.[20] Benenson resigned as Amnesty's president on the grounds that it was bugged and infiltrated by the secret services, and said that he could no longer live in a country where such activities were tolerated.[17] (See Relationship with the British Government)

1970s–1980s

Amnesty International's membership increased from 15,000 in 1969[21] to 200,000 by 1979.[22] At the intergovernmental level Amnesty International pressed for the application of the UN's Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners and of existing humanitarian conventions; to secure ratifications of the two UN Covenants on Human Rights in 1976, and was instrumental in obtaining additional instruments and provisions forbidding the practice of maltreatment. Consultative status was granted at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in 1972.[23]

Amnesty International established its Japan chapter in 1970, in part a response to the Republic of China (Taiwan)'s arrest and prosecution of Chen Yu-hsi, whom the Taiwan Garrison Command had alleged committed sedition by reading communist literature while studying in the United States.[24]: 101–104

In 1976, Amnesty's British Section started a series of fund-raising events that came to be known as The Secret Policeman's Balls series. They were staged in London initially as comedy galas featuring what The Daily Telegraph called "the crème de la crème of the British comedy world"[25] including members of comedy troupe Monty Python, and later expanded to also include performances by leading rock musicians. The series was created and developed by Monty Python alumnus John Cleese and entertainment industry executive Martin Lewis working closely with Amnesty staff members Peter Luff (assistant director of Amnesty 1974–1978) and subsequently with Peter Walker (Amnesty Fund-Raising Officer 1978–1982). Cleese, Lewis and Luff worked together on the first two shows (1976 and 1977). Cleese, Lewis and Walker worked together on the 1979 and 1981 shows, the first to carry what The Daily Telegraph described as the "rather brilliantly re-christened" Secret Policeman's Ball title.[25]

The organization was awarded the 1977 Nobel Peace Prize for its "defence of human dignity against torture"[26] and the United Nations Prize in the Field of Human Rights in 1978.[27]

During the mid-to-late-1980s, Amnesty organized two major musical events took place to increase awareness of Amnesty and of human rights. The 1986 Conspiracy of Hope tour, which played five concerts in the US, and culminated in a daylong show, featuring some thirty-odd acts at Giants Stadium, and the 1988 Human Rights Now! world tour. Human Rights Now!, which was timed to coincide with the 40th anniversary of the United Nations' Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), played a series of concerts on five continents over six weeks. Both tours featured some of the most famous musicians and bands of the day.[citation needed]

1990s

Throughout the 1990s, Amnesty continued to grow, to a membership of over seven million in over 150 countries and territories,[1] led by Senegalese Secretary General Pierre Sané. At the intergovernmental level, Amnesty International argued in favour of creating a United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (established 1993) and an International Criminal Court (established 2002).[citation needed]

Amnesty continued to work on a wide range of issues and world events. For example, South African groups joined in 1992 and hosted a visit by Pierre Sané to meet with the apartheid government to press for an investigation into allegations of police abuse, an end to arms sales to the African Great Lakes region and the abolition of the death penalty. In particular, Amnesty International brought attention to violations committed on specific groups, including refugees, racial/ethnic/religious minorities, women and those executed or on Death Row.[28]

In 1995, when AI wanted to promote how Shell Oil Company was involved with the execution of an environmental and human-rights activist Ken Saro-Wiwa in Nigeria, it was stopped. Newspapers and advertising companies refused to run AI's ads because Shell Oil was a customer of theirs as well. Shell's main argument was that it was drilling oil in a country that already violated human rights and had no way to enforce human-rights policies. To combat the buzz that AI was trying to create, it immediately publicized how Shell was helping to improve overall life in Nigeria. Salil Shetty, the director of Amnesty, said, "Social media re-energises the idea of the global citizen".[15] James M. Russell notes how the drive for profit from private media sources conflicts with the stories that AI wants to be heard.[29]

Amnesty International became involved in the legal battle over Augusto Pinochet, former Chilean dictator, who sought to avoid extradition to Spain to face charges after his arrest in London in 1998 by the Metropolitan Police. Lord Hoffman had an indirect connection with Amnesty International, and this led to an important test for the appearance of bias in legal proceedings in UK law. There was a suit[30] against the decision to release Senator Pinochet, taken by the then British Home Secretary Jack Straw, before that decision had actually been taken, in an attempt to prevent the release of Senator Pinochet. The English High Court refused[31] the application, and Senator Pinochet was released and returned to Chile.

2000s

After 2000, Amnesty International's primary focus turned to the challenges arising from globalization and the reaction to the 11 September 2001 attacks in the United States. The issue of globalization provoked a major shift in Amnesty International policy, as the scope of its work was widened to include economic, social and cultural rights, an area that it had declined to work on in the past. Amnesty International felt this shift was important, not just to give credence to its principle of the indivisibility of rights, but because of what it saw as the growing power of companies and the undermining of many nation-states as a result of globalization.[32]

In the aftermath of 11 September attacks, the new Amnesty International Secretary General, Irene Khan, reported that a senior government official had said to Amnesty International delegates: "Your role collapsed with the collapse of the Twin Towers in New York."[33] In the years following the attacks, some[who?] believe that the gains made by human rights organizations over previous decades had possibly been eroded.[34] Amnesty International argued that human rights were the basis for the security of all, not a barrier to it. Criticism came directly from the Bush administration and The Washington Post, when Khan, in 2005, likened the US government's detention facility at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to a Soviet Gulag.[35][36]

During the first half of the new decade, Amnesty International turned its attention to violence against women, controls on the world arms trade, concerns surrounding the effectiveness of the UN, and ending torture.[37] With its membership close to two million by 2005,[38] Amnesty continued to work for prisoners of conscience.

In 2007, AI's executive committee decided to support access to abortion "within reasonable gestational limits...for women in cases of rape, incest or violence, or where the pregnancy jeopardizes a mother's life or health".[39]

Amnesty International reported, concerning the Iraq War, on 17 March 2008, that despite claims the security situation in Iraq has improved in recent months, the human rights situation is disastrous, after the start of the war five years earlier in 2003.[40]

In 2009, Amnesty International accused Israel and the Palestinian Hamas movement of committing war crimes during Israel's January offensive in Gaza, called Operation Cast Lead, that resulted in the deaths of more than 1,400 Palestinians and 13 Israelis.[41] The 117-page Amnesty report charged Israeli forces with killing hundreds of civilians and wanton destruction of thousands of homes. Amnesty found evidence of Israeli soldiers using Palestinian civilians as human shields. A subsequent United Nations Fact Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict was carried out; Amnesty stated that its findings were consistent with those of Amnesty's own field investigation, and called on the UN to act promptly to implement the mission's recommendations.[42][43]

2010s

Early 2010s

In February 2010, Amnesty suspended Gita Sahgal, its gender unit head, after she criticized Amnesty for its links with Moazzam Begg, director of Cageprisoners. She said it was "a gross error of judgment" to work with "Britain's most famous supporter of the Taliban".[44][45] Amnesty responded that Sahgal was not suspended "for raising these issues internally... [Begg] speaks about his own views ..., not Amnesty International's".[46] Among those who spoke up for Sahgal were Salman Rushdie,[47] Member of Parliament Denis MacShane, Joan Smith, Christopher Hitchens, Martin Bright, Melanie Phillips, and Nick Cohen.[45][48][49][50][51][52][53]

In July 2011, Amnesty International celebrated its 50 years with an animated short film directed by Carlos Lascano, produced by Eallin Motion Art and Dreamlife Studio, with music by Academy Award-winner Hans Zimmer and nominee Lorne Balfe.[54]

In August 2012, Amnesty International's chief executive in India sought an impartial investigation, led by the United Nations, to render justice to those affected by war crimes in Sri Lanka.[55]

Mid-2010s

On 18 August 2014, in the wake of demonstrations sparked by people protesting about the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed 18-year-old who assaulted a police officer and then resisted arrest, and subsequent acquittal of Darren Wilson, the officer who shot him, Amnesty International sent a 13-person contingent of human rights activists to seek meetings with officials as well as to train local activists in non-violent protest methods.[56] This was the first time that the organization has deployed such a team to the United States.[57][58][59]

In the 2015 annual Amnesty International UK conference, delegates narrowly voted (468 votes to 461) against a motion proposing a campaign against antisemitism in the UK. The debate on the motion formed a consensus that Amnesty should fight "discrimination against all ethnic and religious groups", but the division among delegates was over the issue of whether it would be appropriate for an anti-racism campaign with a "single focus".[60][61] The Jewish Chronicle noted that Amnesty International had previously published a report on discrimination against Muslims in Europe.[62]

In August 2015, The Times reported that Yasmin Hussein, then Amnesty's director of faith and human rights and previously its head of international advocacy and a prominent representative at the United Nations, had "undeclared private links to men alleged to be key players in a secretive network of global Islamists", including the Muslim Brotherhood and Hamas.[63][64] The Times also detailed instances where Hussein was alleged to have had inappropriately close relationships with the al-Qazzaz family, members of which were high-ranking government ministers in the administration of Mohammed Morsi and Muslim Brotherhood leaders at the time.[63][64] Ms Hussein denied supporting the Muslim Brotherhood and told Amnesty that "any connections are purely circumstantial".[63]

In June 2016, Amnesty International called on the United Nations General Assembly to "immediately suspend" Saudi Arabia from the UN Human Rights Council.[65][66] Richard Bennett, head of Amnesty's UN Office, said: "The credibility of the U.N. Human Rights Council is at stake. Since joining the council, Saudi Arabia's dire human rights record at home has continued to deteriorate and the coalition it leads has unlawfully killed and injured thousands of civilians in the conflict in Yemen."[67]

In December 2016, Amnesty International revealed that Voiceless Victims, a fake non-profit organization which claims to raise awareness for migrant workers who are victims of human rights abuses in Qatar, had been trying to spy on their staff.[68][69]

Late 2010s

In October 2018, an Amnesty International researcher was abducted and beaten while observing demonstrations in Magas, the capital of Ingushetia, Russia.[70]

On 25 October, federal officers raided the Bengaluru office for 10 hours on a suspicion that the organization had violated foreign direct investment guidelines on the orders of the Enforcement Directorate. Employees and supporters of Amnesty International say this is an act to intimidate organizations and people who question the authority and capabilities of government leaders. Aakar Patel, the executive director of the Indian branch claimed, "The Enforcement Directorate's raid on our office today shows how the authorities are now treating human rights organizations like criminal enterprises, using heavy-handed methods. On Sep 29, the Ministry of Home Affairs said Amnesty International using "glossy statements" about humanitarian work etc. as a "ploy to divert attention" from their activities which were in clear contravention of laid down Indian laws. Amnesty International received permission only once in Dec 2000, since then it had been denied Foreign Contribution permission under the Foreign Contribution Act by successive Governments. However, in order to circumvent the FCRA regulations, Amnesty UK remitted large amounts of money to four entities registered in India by classifying it as Foreign Direct Investment (FDI).[71]

The current Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi, has been criticized by foreign medias for harming civil society in India, specifically by targeting advocacy groups.[72][73][74] India has cancelled the registration of about 15,000 nongovernmental organizations under the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA); the U.N. has issued statements against the policies that allow these cancellations to occur.[75][76] Though nothing was found to confirm these accusations, the government plans on continuing the investigation and has frozen the bank accounts of all the offices in India. A spokesperson for the Enforcement Directorate has said the investigation could take three months to complete.[75]

On 30 October 2018, Amnesty called for the arrest and prosecution of Nigerian security forces claiming that they used excessive force against Shi'a protesters during a peaceful religious procession around Abuja, Nigeria. At least 45 were killed and 122 were injured during the event.[77]

In November 2018, Amnesty reported the arrest of 19 or more rights activists and lawyers in Egypt. The arrests were made by the Egyptian authorities as part of the regime's ongoing crackdown on dissent. One of the arrested was Hoda Abdel-Monaim, a 60-year-old human rights lawyer and former member of the National Council for Human Rights. Amnesty reported that following the arrests Egyptian Coordination for Rights and Freedoms (ECRF) decided to suspend its activities due to the hostile environment towards civil society in the country.[78]

On 5 December 2018, Amnesty International strongly condemned the execution of the leaders of the "black realtors" gang Ihar Hershankou and Siamion Berazhnoy in Belarus.[79] They were shot despite UN Human Rights Committee request for a delay.[80][81]

In February 2019, Amnesty International's management team offered to resign after an independent report found what it called a "toxic culture" of workplace bullying, and found evidence of bullying, harassment, sexism and racism, after being asked to investigate the suicides of 30-year Amnesty veteran Gaetan Mootoo in Paris in May 2018 (who left a note citing work pressures), and 28-year-old intern Rosalind McGregor in Geneva in July 2018.[82]

In April 2019, Amnesty International's deputy director for research in Europe, Massimo Moratti, warned that if extradited to the United States, WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange would face the "risk of serious human rights violations, namely detention conditions, which could violate the prohibition of torture".[83]

On 14 May 2019, Amnesty International filed a petition with the District Court of Tel Aviv, Israel, seeking a revocation of the export licence of surveillance technology firm NSO Group.[84] The filing states that "staff of Amnesty International have an ongoing and well-founded fear they may continue to be targeted and ultimately surveilled"[85] by NSO technology. Other lawsuits have also been filed against NSO in Israeli courts over alleged human-rights abuses, including a December 2018 filing by Saudi dissident Omar Abdulaziz, who claimed NSO's software targeted his phone during a period in which he was in regular contact with murdered journalist Jamal Kashoggi.[86]

In September 2019, European Commission President-elect Ursula von der Leyen created the new position of "Vice President for Protecting our European Way of Life", who will be responsible for upholding the rule-of-law, internal security and migration.[87] Amnesty International accused the European Union of "using the framing of the far right" by linking migration with security.[88]

On 24 November 2019, Anil Raj, a former Amnesty International board member, was killed by a car bomb while working with the United Nations Development Project. U.S. Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo announced Raj's death at a briefing 26 Nov, during which he discussed other acts of terrorism.[89]

2020s

In August 2020, Amnesty International expressed concerns about what it called the "widespread torture of peaceful protesters" and treatment of detainees in Belarus.[90] The organization also said that more than 1,100 people were killed by bandits in rural communities in northern Nigeria during the first six months of 2020.[91] Amnesty International investigated what it called "excessive" and "unlawful" killings of teenagers by Angolan police who were enforcing restrictions during the coronavirus pandemic.[92]

In May 2020, the organization raised concerns about security flaws in a COVID-19 contact tracing app mandated in Qatar.[93]

In September 2020, Amnesty shut down its India operations after the government froze its bank accounts due to alleged financial irregularities.[94]

On 2 November 2020, Amnesty International reported that 54 people – mostly Amhara women and children and elderly people – were killed by the OLF in the village of Gawa Qanqa, Ethiopia.[95][96]

In April 2021, Amnesty International distanced itself from a tweet by Agnès Callamard, its newly appointed Secretary General, asserting that Israel had killed Yasser Arafat; Callamard herself has not deleted the tweet.[97][98][99]

In February 2022, Amnesty accused Israel of committing the crime of apartheid against the Palestinians, joining other human rights organizations that had previously accused Israel of the crime against humanity. In 2021, Human Rights Watch and B'tselem both accused Israel of apartheid for its treatment of the Palestinians in the occupied territories.[100] An Amnesty report stated that Israel maintains "an institutionalized regime of oppression and domination of the Palestinian population for the benefit of Jewish Israelis".[101] The Israeli Foreign Ministry stated that Amnesty was peddling "lies, inconsistencies, and unfounded assertions that originate from well-known anti-Israeli hate organisations". The Palestinian Foreign Ministry called the report a "detailed affirmation of the cruel reality of entrenched racism, exclusion, oppression, colonialism, apartheid, and attempted erasure that the Palestinian people have endured".[101]

In March 2022, Paul O'Brien, the Amnesty International USA Director, speaking to a Women's National Democratic Club audience in the US, stated: "We are opposed to the idea—and this, I think, is an existential part of the debate—that Israel should be preserved as a state for the Jewish people", while adding "Amnesty takes no political views on any question, including the right of the State of Israel to survive."[102][103][104][105][undue weight? – discuss]

On 7 April 2022, six weeks after the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Russian Ministry of Justice announced that the offices of Amnesty International and 14 other well-known international organizations had been closed for "violations of Russian law".[106]

Structure

Amnesty International is largely made up of voluntary members but retains a small number of paid professionals. In countries in which Amnesty International has a strong presence, members are organized as "sections". In 2019 there were 63 sections worldwide.[107] The highest governing body is the Global Assembly which meets annually, attended by the chair and executive director of each section.

The International Secretariat (IS) is responsible for the conduct and daily affairs of Amnesty International under direction from the International Board.[108] It is run by approximately 500 professional staff members and is headed by a Secretary General. Its offices have been located in London since its establishment in the mid-1960s.

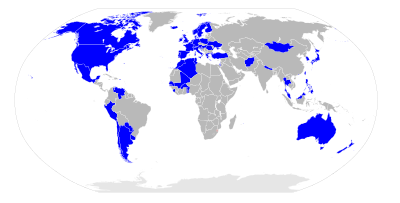

- Amnesty International Sections, 2005

Algeria; Argentina; Australia; Austria; Belgium (Dutch-speaking); Belgium (French-speaking); Benin; Bermuda; Canada (English-speaking); Canada (French-speaking); Chile; Côte d'Ivoire; Denmark; Faroe Islands; Finland; France; Germany; Greece; Guyana; Hong Kong; Iceland; Ireland; Israel; Italy; Japan; Korea (Republic of); Luxembourg; Mauritius; Mexico; Morocco; Nepal; Netherlands; New Zealand; Norway; Peru; Philippines; Poland; Portugal; Puerto Rico; Senegal; Sierra Leone; Slovenia; Spain; Sweden; Switzerland; Taiwan; Togo; Tunisia; United Kingdom; United States of America; Uruguay; Venezuela - Amnesty International Structures, 2005

Belarus; Bolivia; Burkina Faso; Croatia; Curaçao; Czech Republic; Gambia; Hungary; Malaysia; Mali; Moldova; Mongolia; Pakistan; Paraguay; Slovakia; South Africa; Thailand; Turkey; Ukraine; Zambia; Zimbabwe - International Board (formerly known as "IEC") Chairpersons

Seán MacBride, 1965–74; Dirk Börner, 1974–17; Thomas Hammarberg, 1977–79; José Zalaquett, 1979–82; Suriya Wickremasinghe, 1982–85; Wolfgang Heinz, 1985–96; Franca Sciuto, 1986–89; Peter Duffy, 1989–91; Anette Fischer, 1991–92; Ross Daniels, 1993–19; Susan Waltz, 1996–98; Mahmoud Ben Romdhane, 1999–2000; Colm O Cuanachain, 2001–02; Paul Hoffman, 2003–04; Jaap Jacobson, 2005; Hanna Roberts, 2005–06; Lilian Gonçalves-Ho Kang You, 2006–07; Peter Pack, 2007–11; Pietro Antonioli, 2011–13; and Nicole Bieske, 2013–2018, Sarah Beamish (2019 to current). - Secretaries General

| Secretary General | Office | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| Peter Benenson | 1961–1966 | Britain |

| Eric Baker | 1966–1968 | Britain |

| Martin Ennals | 1968–1980 | Britain |

| Thomas Hammarberg | 1980–1986 | Sweden |

| Ian Martin | 1986–1992 | Britain |

| Pierre Sané | 1992–2001 | Senegal |

| Irene Khan | 2001–2010 | Bangladesh |

| Salil Shetty | 2010–2018 | India |

| Kumi Naidoo | 2018–2020[109] | South Africa |

| Julie Verhaar | 2020–2021 (Acting) | |

| Agnès Callamard | 2021–present[2] | France |

Notable national sections

- Amnesty International Ghana

- Amnesty International Australia

- Amnesty International India

- Amnesty International Ireland

- Amnesty International New Zealand

- Amnesty International Philippines

- Amnesty International South Africa

- Amnesty International Thailand

- Amnesty International USA

Charitable status

In the UK Amnesty International has two components which are registered charities under English law: Amnesty International Charity[110] and Amnesty International UK Section Charitable Trust.[111]

Principles

The core principle of Amnesty International is a focus on prisoners of conscience, those persons imprisoned or prevented from expressing an opinion by means of violence. Along with this commitment to opposing repression of freedom of expression, Amnesty International's founding principles included non-intervention on political questions, a robust commitment to gathering facts about the various cases and promoting human rights.[112]

One key issue in the principles is in regards to those individuals who may advocate or tacitly support resorting to violence in struggles against repression. AI does not judge whether recourse to violence is justified or not. However, AI does not oppose the political use of violence in itself since The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, in its preamble, foresees situations in which people could "be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression". If a prisoner is serving a sentence imposed, after a fair trial, for activities involving violence, AI will not ask the government to release the prisoner.

AI neither supports nor condemns the resort to violence by political opposition groups in itself, just as AI neither supports nor condemns a government policy of using military force in fighting against armed opposition movements. However, AI supports minimum humane standards that should be respected by governments and armed opposition groups alike. When an opposition group tortures or kills its captives, takes hostages, or commits deliberate and arbitrary killings, AI condemns these abuses.[113][dubious – discuss]

Amnesty International considers capital punishment to be the ultimate, irreversible denial of human rights and opposes capital punishment in all cases, regardless of the crime committed, the circumstances surrounding the individual or the method of execution.[114]

Objectives

Amnesty International's vision is of a world in which every person enjoys all of the human rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards.

In pursuit of this vision, Amnesty International's mission is to undertake research and action focused on preventing and ending grave abuses of the rights to physical and mental integrity, freedom of conscience and expression, and freedom from discrimination, within the context of its work to promote all human rights.

Amnesty International primarily targets governments, but also reports on non-governmental bodies and private individuals ("non-state actors").

There are six key areas which Amnesty deals with:[115]

- Women's, children's, minorities' and indigenous rights

- Ending torture

- Abolition of the death penalty

- Rights of refugees

- Rights of prisoners of conscience

- Protection of human dignity.

Some specific aims are to: abolish the death penalty,[114] end extra judicial executions and "disappearances", ensure prison conditions meet international human rights standards, ensure prompt and fair trial for all political prisoners, ensure free education to all children worldwide, decriminalize abortion,[116] fight impunity from systems of justice, end the recruitment and use of child soldiers, free all prisoners of conscience, promote economic, social and cultural rights[117] for marginalized communities, protect human rights defenders, promote religious tolerance, protect LGBT rights,[118] stop torture and ill-treatment,[119] stop unlawful killings in armed conflict,[120] uphold the rights of refugees,[121] migrants, and asylum seekers, and protect human dignity. They also support worldwide decriminalisation of prostitution.[122]

Amnesty International launched a free human rights learning mobile application called Amnesty Academy in October 2020. It offered learners across the globe access to courses both, online and offline. All courses are downloadable within the application, which is available for both iOS and Android devices.[123]

Country focus

Amnesty reports disproportionately on relatively more democratic and open countries,[124] arguing that its intention is not to produce a range of reports which statistically represents the world's human rights abuses, but rather to apply the pressure of public opinion to encourage improvements.

The demonstration effect of the behaviour of both key Western governments and major non-Western states is an important factor; as one former Amnesty Secretary-General pointed out, "for many countries and a large number of people, the United States is a model", and according to one Amnesty manager, "large countries influence small countries."[125] In addition, with the end of the Cold War, Amnesty felt that a greater emphasis on human rights in the North was needed to improve its credibility with its Southern critics by demonstrating its willingness to report on human rights issues in a truly global manner.[125]

According to one academic study, as a result of these considerations, the frequency of Amnesty's reports is influenced by a number of factors, besides the frequency and severity of human rights abuses. For example, Amnesty reports significantly more (than predicted by human rights abuses) on more economically powerful states; and on countries that receive US military aid, on the basis that this Western complicity in abuses increases the likelihood of public pressure being able to make a difference.[125] In addition, around 1993–94, Amnesty consciously developed its media relations, producing fewer background reports and more press releases, to increase the impact of its reports. Press releases are partly driven by news coverage, to use existing news coverage as leverage to discuss Amnesty's human rights concerns. This increases Amnesty's focus on the countries the media is more interested in.[125]

In 2012, Kristyan Benedict, Amnesty UK's campaign manager whose main focus is Syria, listed several countries as "regimes who abuse peoples' basic universal rights": Burma, Iran, Israel, North Korea and Sudan. Benedict was criticized for including Israel in this short list on the basis that his opinion was garnered solely from "his own visits", with no other objective sources.[126][127]

Amnesty's country focus is similar to that of some other comparable NGOs, notably Human Rights Watch: between 1991 and 2000, Amnesty and HRW shared eight of ten countries in their "top ten" (by Amnesty press releases; 7 for Amnesty reports).[125] In addition, six of the 10 countries most reported on by Human Rights Watch in the 1990s also made The Economist's and Newsweek's "most covered" lists during that time.[125]

Funding

Amnesty International is financed largely by fees and donations from its worldwide membership. It says that it does not accept donations from governments or governmental organizations.[128]

However, Amnesty International has received grants over the past ten years from the UK Department for International Development,[129] the European Commission,[130] the United States State Department[131][132] and other governments.[133][134]

Amnesty International USA has received funding from the Rockefeller Foundation,[135] but these funds are only used "in support of its human rights education work."[129] It has also received many grants from the Ford Foundation over the years.[136]

Criticism and controversies

Criticism of Amnesty International includes claims about publishing incorrect reports, associating with organizations with a dubious record on human rights protection, selection bias, ideological and foreign policy bias, and the issue of institutional discrimination within the organization.[137] Following the suicide of two staff members in 2019, Amnesty launched a review of the workplace culture at the organization. The report found an internal toxic work environment, including cases of bullying and discrimination.[138] Since the report multiple staff members around the world spoke about systemic abuse at Amnesty.[139]

Numerous governments and their supporters have criticized Amnesty's criticism of their policies, including those of Australia;[140] Czech Republic;[141] China;[142] the Democratic Republic of the Congo;[143] Egypt;[144] India; Iran; Israel;[127] Morocco;[145] Qatar;[146] Saudi Arabia;[147] Vietnam;[148] Russia;[149] Nigeria;[150] and the United States,[151] for what they assert is one-sided reporting or a failure to treat threats to security as a mitigating factor. The actions of these governments, and of other governments critical of Amnesty International, have been the subject of human rights concerns voiced by Amnesty.

Internal controversies

2019 report on workplace bullying

In February 2019, Amnesty International's management team offered to resign after an independent report found what it called a "toxic culture" of workplace bullying. Evidence of bullying, harassment, sexism and racism was uncovered after two 2018 suicides were investigated: that of 30-year Amnesty veteran Gaëtan Mootoo in Paris in May 2018 (who left a note citing work pressures); and that of 28-year-old intern Rosalind McGregor in Geneva in July 2018.[82] An internal survey by the Konterra group with a team of psychologists was conducted in January 2019, after the 2 employees had killed themselves in 2018. The report stated that Amnesty had a toxic work culture and that workers frequently cited mental and physical health issues as a result of their work for the organization. The report found that: "39 per cent of Amnesty International staff reported that they developed mental or physical health issues as the direct result of working at Amnesty". The report concluded, "organisational culture and management failures are the root cause of most staff wellbeing issues."[152]

Elaborating on this the report mentioned that bullying, public humiliation and other abuses of power are commonplace and routine practice by the management. It also claimed the us versus them culture among employees and the severe lack of trust in the senior management at Amnesty.[153][154] By October 2019 five of the seven members of the senior leadership team at Amnesty's international secretariat left the organization with "generous" redundancy packages.[155] Among them, Anna Neistat, who was Gaëtan Mootoo's senior manager directly implicated in the independent report on Mootoo's death. According to Mootoo's former collaborator, Salvatore Saguès, "Gaëtan's case is merely the tip of the iceberg at Amnesty. A huge amount of suffering is caused to employees. Since the days of Salil Shetty, when top management were being paid fabulous salaries, Amnesty has become a multinational where the staff are seen as dispensable. Human resources management is a disaster and nobody is prepared to stand up and be counted. The level of impunity granted to Amnesty's bosses is simply unacceptable."[156] After none of the managers responsible of bullying at Amnesty were held accountable a group of workers petitioned for Amnesty's chief Kumi Naidoo to resign. On 5 December 2019 Naidoo resigned from his post of Amnesty's Secretary General citing ill health[157] and appointing Julie Verhaar as an interim Secretary General. In their petition, workers demanded her immediate resignation as well.

2019 budgetary crisis

In May 2019, Amnesty International's Secretary General Kumi Naidoo admitted to a hole in the organization's budget of up to £17m in donor money to the end of 2020. In order to deal with the budgetary crisis, Naidoo announced to staff that the organization's headquarters would have cut almost 100 jobs as a part of urgent restructuring. Unite the Union, the UK's biggest trade union, said the redundancies were a direct result of "overspending by the organization's senior leadership team" and have occurred "despite an increase in income".[158] Unite, which represents Amnesty's staff, feared that cuts would fall heaviest on lower-income staff. It said that in the previous year the top 23 highest earners at Amnesty International were paid a total of £2.6m– an average of £113,000 per year. Unite demanded a review of whether it is necessary to have so many managers in the organization.[159]

Amnesty's budgetary crisis became public after the two staff suicides in 2019. A subsequent independent review of workplace culture found a "state of emergency" at the organization after a restructuring process. Following several reports that labelled Amnesty a toxic workplace, in October 2019 five of the seven high-paid senior directors at Amnesty's international secretariat in London left the organization with "generous" redundancy packages.[160] This included Anna Neistat, who was a senior manager directly implicated in the independent report on the suicide of Amnesty's West Africa researcher Gaëtan Mootoo in the organization's Paris office. The size of exit packages granted to former senior management caused anger among other staff and an outcry among Amnesty's members,[161] and led to the resignation of Naidoo in December 2019.[162]

2020 secret payout

In September 2020, The Times reported that Amnesty International paid £800,000 in compensation over the workplace suicide of Gaëtan Mootoo and demanded his family keep the deal secret.[163] The pre-trial agreement between London-based Amnesty's International Secretariat and Motoo's wife was reached on the condition that she keeps the deal secret by signing NDA. This was done particularly to prevent discussing the settlement with the press or on social media. The arrangement led to criticism on social media, with people asking why an organization such as Amnesty would condone the use of non-disclosure agreements. Shaista Aziz, a co-founder of the feminist advocacy group NGO Safe Space, questioned on Twitter why the "world's leading human rights organisation" was employing such contracts.[164] The source of the money was unknown. Amnesty stated that the payout to Motoo's family "will not be made from donations or membership fees".

2021 accusation of systemic bias

In April 2021, The Guardian reported that the workers of Amnesty International alleged systemic bias and use of racist language by senior staff.[165]

The internal review at Amnesty's international secretariat, the report of which was published in October 2020 but not released to the press, recorded multiple examples of alleged racism reported by workers—racial slurs, systemic bias, problematic comments towards religious practices, being some of the examples.[165][166]

The staff at the Amnesty International UK based in London also made claims of racial discrimination.[165] The report also documented use of the ethnic slur "nigger" with any objection from employees about its use being downplayed. Vanessa Tsehaye, the Horn of Africa Campaigner based in the UK, has refused to comment as of April 2021.

2022 report on systemic racism

In June 2022, a 106-page independent investigation by the management consultancy firm Global HPO Ltd (GHPO) concluded that Amnesty International UK (AIUK) exhibits institutional and systemic racism. This report was fully accepted by Amnesty International and Amnesty International UK published the findings of the inquiry in April 2022.[167] GHPO's independent investigation found that UKAIUK "has failed to embed principles of anti-racism into its own DNA and faces bullying issues within the organisation."[168]

GHPO's report includes recommendations for improvement actions to be taken by the organization. The alghemeiner reports that AIUK stated it "accepted all the recommendations," and that the "press' insistence on describing Amnesty as a 'leading human rights group' is furthermore problematic given the anti-Jewish racism that the NGO has displayed for years."[169]

Nayirah testimony

In 1990, when the United States government was deciding whether or not to invade Iraq, a Kuwaiti woman, only identified to Congress by the first name Nayirah, testified to congress that when Iraq invaded Kuwait, she stayed behind after some of her family left the country. She said she was volunteering in a local hospital when Iraqi soldiers stole the incubators with children in them and left them to freeze to death. Amnesty International, which had human rights investigators in Kuwait, confirmed the story and helped spread it among the Western public. The organization also inflated the number of children who were killed by the robbery to over 300, more than the number of incubators available in the city hospitals of the country. Her testimony aired on ABC's Nightline and NBC Nightly News reaching an estimated audience between 35 and 53 million Americans.[170][171] Seven senators cited Nayirah's testimony in their speeches backing the use of force.[174] President George Bush repeated the story at least ten times in the following weeks.[175] Her account of the atrocities helped to stir American opinion in favour of participation in the Gulf War.[176] It was often cited by people, including the members of Congress who voted to approve the Gulf War, as one of the reasons to fight. After the war, it was found that the testimony was entirely fabricated and that "Nayirah" was in fact the daughter of a Kuwaiti delegate to America with a leading role in the pro-war think tank responsible for organizing the hearing.[177]

Israel

In 2010 Frank Johansson, the chairman of Amnesty International-Finland, called Israel a nilkkimaa, a derogatory term variously translated as "scum state", "creep state" or "punk state".[178][179] Johansson stood by his statement, saying that it was based on Israel's "repeated flouting of international law", and his own personal experiences with Israelis. When asked by a journalist if any other country on earth that could be described in these terms, he said that he could not think of any, although some individual "Russian officials" could be so described.[179]

In November 2012, Amnesty UK began a disciplinary process against staffer Kristyan Benedict, Amnesty UK campaigns manager, because of a posting on his Twitter account, said to be anti-semitic, regarding three Jewish members of parliament and Operation Pillar of Defense where he wrote: "Louise Ellman, Robert Halfon and Luciana Berger walk into a bar ... each orders a round of B52s ... #Gaza". Amnesty International UK said "the matter has been referred to our internal and confidential processes." Amnesty's campaigns director Tim Hancock said, "We do not believe that humour is appropriate in the current circumstances, particularly from our own members of staff." An Amnesty International UK spokesperson later said the charity had decided that "the tweet in question was ill-advised and had the potential to be offensive and inflammatory but was not racist or antisemitic."[180][181][182]

In November 2016, Amnesty International conducted a second internal investigation of Benedict for comparing Israel to the Islamic state.[183]

In April 2021, Amnesty International distanced itself from a tweet written in 2013 by its new Secretary General, Agnès Callamard, which read: ""NYT Interview of Shimon Perres [sic] where he admits that Yasser Arafat was murdered"; Amnesty responded by saying: "The tweet was written in haste and is incorrect. It does not reflect the position of Amnesty International or Agnès Callamard."[184][185][186] Callamard herself has not deleted the tweet.[184]

On 11 March 2022, Paul O'Brien, the Amnesty International USA Director, stated at a private event: "We are opposed to the idea — and this, I think, is an existential part of the debate — that Israel should be preserved as a state for the Jewish people", while adding "Amnesty takes no political views on any question, including the right of the State of Israel to survive."[187][188][189][190] He also rejected a poll that found 8 in 10 American Jews were pro-Israel, saying: "I believe my gut tells me that what Jewish people in this country want is to know that there's a sanctuary that is a safe and sustainable place that the Jews, the Jewish people can call home."[187][188][189] On 14 March 2022, all 25 Jewish Democrats in the House of Representatives issued a rare joint statement rebuking O'Brien, saying that he "has added his name to the list of those who, across centuries, have tried to deny and usurp the Jewish people's independent agency" and "condemning this and any antisemitic attempt to deny the Jewish people control of their own destiny."[191][192][193] On 25 March 2022, O'Brien wrote to the Jewish congressmen: "I regret representing the views of the Jewish people."[192]

Russia

Amnesty International designated Alexei Navalny a prisoner of conscience in 2012.[194] However, in February 2021, it stripped Navalny of the status, due to lobbying about videos and pro-nationalist statements he made in 2007-2008 that allegedly constituted hate speech.[195][196][197][198] Amnesty's decision was described by western media as "a huge victory for Russian state propaganda" which undermined Amnesty's support of Navalny's release.[199][200] The designation of Navalny as a prisoner of conscience was reinstated in May 2021. Amnesty apologized for making the decision and stated that "by confirming Navalny's status as prisoner of conscience, we are not endorsing his political programme, but are highlighting the urgent need for his rights, including access to independent medical care, to be recognized and acted upon by the Russian authorities."[201][202]

United Kingdom and the Commonwealth

During the early history of Amnesty International, as it is now proven by various documents, it was secretly supported by the Foreign Office. In 1963, the FO instructed its operatives abroad to provide "discreet support" for Amnesty's campaigns. In the same year, Benenson wrote to Minister of State for the Colonies Lord Lansdowne a proposal to prop up a "refugee counsellor" on the border between the Bechuanaland Protectorate and apartheid South Africa. Amnesty intended to assist people fleeing across the border from neighbouring South Africa, but not those who were actively engaged in the struggle against apartheid. Benenson wrote:

I would like to reiterate our view that these [British] territories should not be used for offensive political action by the opponents of the South African Government (...) Communist influence should not be allowed to spread in this part of Africa, and in the present delicate situation, Amnesty International would wish to support Her Majesty's Government in any such policy.[17]

The year after, the AI dropped Nelson Mandela as a "prisoner of conscience", because he was convicted of violence by the South African Government. Mandela had also been a member of the South African Communist Party.[203]

In a trip to Haiti, the British FO had also assisted Benenson in his mission to Haiti, where he was disguised because of fear of the Haitians finding out that the British government sponsored his visit. When his disguise was revealed, Benenson was severely criticized by the media.[17]

In the British colony of Aden, Hans Goran Franck, the chairman of Amnesty's Swedish section, wrote a report on allegations of torture at an interrogation centre run by the colonial government. Amnesty refused to publish the report; according to Benenson, Amnesty general-secretary Robert Swann had suppressed it in deference to the Foreign Office. According to co-founder Eric Baker, both Benenson and Swann had met Foreign Secretary George Brown in September and told him that they were willing to hold up publication if the Foreign Office promised no more allegations of torture would surface again. A memo by Lord Chancellor Gerald Gardiner, a Labour Party politician, states that:

Amnesty held the Swedish complaint as long as they could simply because Peter Benenson did not want to do anything to hurt a Labour government.[17]

Benenson then travelled to Aden and reported that he had never seen an "uglier situation" in his life. He then said that British government agents had infiltrated Amnesty and suppress the report's publication. Later, documents surfaced implicating Benenson had connections to the British government, which started the Harry letters affair.[19][17] He then resigned, claiming that British and American intelligence agents had infiltrated Amnesty and subverted its values.[19] After this set of events, which were dubbed by some the "Amnesty Crisis of 1966–67",[204] the relationship between Amnesty and the British Government was suspended. AI vowed that in future, it "must not only be independent and impartial but must not be put into a position where anything else could even be alleged" and the Foreign Office cautioned that "for the time being our attitude to Amnesty International must be one of reserve".[17]

2010 CAGE controversy

Amnesty International suspended Gita Sahgal, its gender unit head, after she criticized Amnesty in February 2010 for its high-profile associations with Moazzam Begg, the director of Cageprisoners, representing men in extrajudicial detention.[205][206]

"To be appearing on platforms with Britain's most famous supporter of the Taliban, Begg, whom we treat as a human rights defender, is a gross error of judgment," she said.[205][207] Sahgal argued that by associating with Begg and Cageprisoners, Amnesty was risking its reputation on human rights.[205][208][209] "As a former Guantanamo detainee, it was legitimate to hear his experiences, but as a supporter of the Taliban it was absolutely wrong to legitimize him as a partner," Sahgal said.[205] She said she repeatedly brought the matter up with Amnesty for two years, to no avail.[210] A few hours after the article was published, Sahgal was suspended from her position.[211] Amnesty's Senior Director of Law and Policy, Widney Brown, later said Sahgal raised concerns about Begg and Cageprisoners to her personally for the first time a few days before sharing them with the Sunday Times.[210]

Sahgal issued a statement saying she felt that Amnesty was risking its reputation by associating with and thereby politically legitimizing Begg, because Cageprisoners "actively promotes Islamic Right ideas and individuals".[211] She said the issue was not about Begg's "freedom of opinion, nor about his right to propound his views: he already exercises these rights fully as he should. The issue is ... the importance of the human rights movement maintaining an objective distance from groups and ideas that are committed to systematic discrimination and fundamentally undermine the universality of human rights."[211] The controversy prompted responses by politicians, the writer Salman Rushdie, and journalist Christopher Hitchens, among others who criticized Amnesty's association with Begg.

After her suspension and the controversy, Sahgal was interviewed by numerous media and attracted international supporters. She was interviewed on the US National Public Radio (NPR) on 27 February 2010, where she discussed the activities of Cageprisoners and why she deemed it inappropriate for Amnesty to associate with Begg.[212] She said that Cageprisoners' Asim Qureshi spoke supporting global jihad at a Hizb ut-Tahrir rally.[212] She stated that a best-seller at Begg's bookshop was a book by Abdullah Azzam, a mentor of Osama bin Laden and a founder of the terrorist organization Lashkar-e-Taiba.[210][212]

In a separate interview for the Indian Daily News & Analysis, Sahgal said that, as Quereshi affirmed Begg's support for global jihad on a BBC World Service programme, "these things could have been stated in his [Begg's] introduction" with Amnesty.[213] She said that Begg's bookshop had published The Army of Madinah, which she characterized as a jihad manual by Dhiren Barot.[214]

2011 Irene Khan payout

In February 2011, newspaper stories in the UK revealed that Irene Khan had received a payment of £533,103 from Amnesty International following her resignation from the organization on 31 December 2009,[215] a fact pointed to from Amnesty's records for the 2009–2010 financial year. The sum paid to her was more than four times her annual salary (£132,490).[215] The deputy secretary general, Kate Gilmore, who also resigned in December 2009, received an ex-gratia payment of £320,000.[215] According to the Daily Express, Peter Pack, the chairman of Amnesty's International Executive Committee (IEC), initially stated on 19 February 2011: "The payments to outgoing secretary general Irene Khan shown in the accounts of AI (Amnesty International) Ltd for the year ending 31 March 2010 include payments made as part of a confidential agreement between AI Ltd and Irene Khan"[216][unreliable source?] and that "It is a term of this agreement that no further comment on it will be made by either party."[215]

The payment and AI's initial response to its leakage to the press led to a considerable outcry. Philip Davies, the Conservative MP for Shipley, criticized the payments, telling the Daily Express: "I am sure people making donations to Amnesty, in the belief they are alleviating poverty, never dreamed they were subsidising a fat cat payout. This will disillusion many benefactors."[216][unreliable source?] On 21 February 2011, Peter Pack issued a further statement, in which he said that the payment was a "unique situation" that was "in the best interest of Amnesty's work" and that there would be no repetition of it.[215] He stated that "the new secretary general, with the full support of the IEC, has initiated a process to review our employment policies and procedures to ensure that such a situation does not happen again."[215] Pack also stated that Amnesty was "fully committed to applying all the resources that we receive from our millions of supporters to the fight for human rights".[215]

On 25 February 2011, Pack sent a letter to Amnesty members and staff. In 2008, it stated, the IEC decided not to prolong Khan's contract for a third term. In the following months, IEC discovered that due to British employment law, it had to choose between three options: offering Khan a third term; discontinuing her post and, in their judgement, risking legal consequences; or signing a confidential agreement and issuing a pay compensation.[217]

2019 Kurdish hunger strike

In April 2019, 30 Kurdish activists, some of whom are on an indefinite hunger strike, occupied Amnesty International's building in London in a peaceful protest, in order to speak out against Amnesty's silence on the isolation of Abdullah Öcalan in a Turkish prison.[218] The hunger strikers have also spoken out about "delaying tactics" by Amnesty, and being denied access to toilets during the occupation, despite this being a human right.[219][220] Two of the hunger strikers, Nahide Zengin and Mehmet Sait Zengin, received paramedic treatment and were taken to hospital during the occupation. Late in the evening of 26 April 2019, the London Met police arrested 21 remaining occupiers.[221][undue weight? – discuss]

Ukraine

On 4 August 2022, during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Amnesty International published a report accusing the Armed Forces of Ukraine of endangering civilians through their combat tactics, particularly stating that Ukraine had set up military bases in residential areas (including schools and hospitals) and launched attacks from populated civilian areas.[222] Oksana Pokalchuk, leader of Amnesty Ukraine, said that the report "was compiled by foreign observers, without any assistance from local staff".[223] She resigned from her post and left the organization following the publication of the report.[224]

Human rights lawyers Wayne Jordash and Anna Mykytenko argued that the 4 August report contained "little to none of the military or humanitarian context essential to any reasoned view of what was (or was not) necessary in the prevailing military context" and that the report was "short on facts and analysis and long on intemperate accusation."[225] RUSI researcher Jack Watling stated that "you need to balance military necessity with proportionality, so you need to take reasonable measures to protect civilians but that must be balanced with your orders to defend an area", thus the report's suggestions that Ukrainian forces should relocate to a nearby field or forest "demonstrated a lack of understanding of military operations and damages the credibility of the research."[226] RUSI researcher Natia Seskuria called the report "out of touch with current reality" and stated that the Ukrainian army can legitimately house in the towns they defend, even if they have civilians nearby, because the Ukrainian authorities constantly call for evacuations from frontline towns, and forced relocations of civilian population would violate international humanitarian law.[227] Marc Garlasco, a United Nations war crimes investigator specializing in civilian harm mitigation, said that "Ukraine can place forces in areas they are defending" and "there is no requirement to stand shoulder to shoulder in a field — this isn't the 19th century", and expressed concern that the report could endanger Ukrainian civilians by giving Russian forces an excuse to "expand their targeting of civilian areas".[228]

Journalist Tom Mutch stated that he had participated in and reported on an evacuation of civilians in one of Amnesty's cases, which he contrasted with Amnesty's statement that it was "not aware that the Ukrainian military who located themselves in civilian structures in residential areas asked or assisted civilians to evacuate nearby buildings".[226] The Kyiv Independent editorial team strongly criticized the report, pointing out flaws in reasoning and stating that the "Amnesty [International] could not properly articulate who the main perpetrator of violence in Ukraine was".[229]

The report sparked outrage in Ukraine and the West. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy accused Amnesty of trying to "amnesty the terrorist state and shift the responsibility from the aggressor to the victim", while Ukraine's Minister of Foreign Affairs, Dmytro Kuleba, stated that the report creates "a false balance between the oppressor and the victim".[228][230][231] The report was praised by several Russian and pro-Russian figures, including the Russian embassy in London, causing further criticism against the organization.[232]

On 12 August, Amnesty International reported that "the conclusions were not conveyed with the delicacy and accuracy that should be expected from Amnesty", and said that "this also applies to the subsequent communication and reaction of the International Secretariat to public criticism." The organization condemned "the instrumentalization of the press release by the Russian authorities" and promised that the report will be verified by independent experts.[233][234]

The criticism resulted in AI calling an internal review committee composed of independent international humanitarian law (IHL) experts to review the report, whose conclusions were not published by AI but nonetheless obtained by New York Times. The review concluded that while AI was right to include Ukraine in its analysis in general as IHL applies to all sides of a conflict, its conclusions in respect to Ukraine were biased and not sufficiently substantiated by available evidence, and the vague language of the report could leave an impression, even if this was not intended and not supported by evidence, that "Ukrainian forces were primarily or equally to blame for the death of civilians resulting from attacks by Russia". To the contrary, the review concluded that on the basis of the evidence that AI had collected it was "simply impossible to assert that generally civilians died" as result of negligence of Ukrainian army, while "imprudent language" of the report suggested this.[235]

Awards and honours

In 1977, Amnesty International was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for "having contributed to securing the ground for freedom, for justice, and thereby also for peace in the world".[236]

In 1984, Amnesty International received the Four Freedoms Award in the category of Freedom of Speech.[237]

Cultural impact

Human rights concerts

A Conspiracy of Hope was a short tour of six benefit concerts on behalf of Amnesty International that took place in the United States during June 1986. The purpose of the tour was not to raise funds but rather to increase awareness of human rights and of Amnesty's work on its 25th anniversary. The shows were headlined by U2, Sting and Bryan Adams and also featured Peter Gabriel, Lou Reed, Joan Baez, and The Neville Brothers. The last three shows featured a reunion of The Police. At a press conference in each city, at related media events, and through their music at the concerts themselves, the artists engaged with the public on themes of human rights and human dignity. The six concerts were the first of what subsequently became known collectively as the Human Rights Concerts – a series of music events and tours staged by Amnesty International USA between 1986 and 1998.

Human Rights Now! was a worldwide tour of twenty benefit concerts on behalf of Amnesty International that took place over six weeks in 1988. Held not to raise funds but to increase awareness of both the Universal Declaration of Human Rights on its 40th anniversary and the work of Amnesty International, the shows featured Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band, Sting, Peter Gabriel, Tracy Chapman, and Youssou N'Dour, plus guest artists from each of the countries where concerts were held.

The Amnesty Candle

The organization's logo combines two recognizable images inspired by the proverb, "Better to light a candle than curse the darkness."[238] The candle represents the organization's efforts to bring light to the fact that political prisoners are held all over the world and its commitment to bring the prisoners hope for fair treatment and release. The barbed wire represents the hopelessness of people unjustly put in jail.[239]

The logo was designed by Diana Redhouse in 1963 as Amnesty's first Christmas card.[240]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ a b The anthropologist Linda Rabben refers to the origin of Amnesty as a "creation myth" with a "kernel of truth": "The immediate impetus to form Amnesty did come from Peter Benenson's righteous indignation while reading a newspaper in the London tube on 19 November 1960."[241] The historian Tom Buchanan traced the origins story to a radio broadcast by Peter Benenson in 1962. The 4 March 1962 BBC news story did not refer to a "toast to liberty", but Benenson said his tube ride was on 19 December 1960. Buchanan was unable to find the newspaper article about the Portuguese students in The Daily Telegraph for either month. Buchanan found many news stories reporting on the repressive Portuguese political arrests in The Times for November 1960.[86]

Citations

- ^ a b c "Who we are". Amnesty International. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ a b "Dr Agnès Callamard appointed as Secretary General of Amnesty International". amnesty.org. 29 March 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ "Amnesty International's Statute". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023.

- ^ Wong, Wendy (2012). Internal Affairs: How the Structure of NGOs Transforms Human Rights. Cornell University Press. p. 84. doi:10.7591/j.cttq43kj (inactive 1 November 2024). ISBN 978-0-8014-5079-2. JSTOR 10.7591/j.cttq43kj.8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Srivastava, Swati (2022), "Shadowing for Human Rights through Amnesty International", Hybrid Sovereignty in World Politics, Cambridge University Press, pp. 185–228, doi:10.1017/9781009204453.007, ISBN 978-1-009-20445-3

- ^ a b c Benenson, Peter (28 May 1961). "The Forgotten Prisoners". The Observer. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ "About Amnesty International". Amnesty International. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- ^ Childs, Peter; Storry, Mike, eds. (2002). "Amnesty International". Encyclopedia of Contemporary British Culture. London: Routledge. pp. 22–23.

- ^ "AGNI Online: Amnesty International: Myth and Reality by Linda Rabben". agnionline.bu.edu. 15 October 2001. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ McKinney, Seamus (29 September 2018). "Sir Louis Blom-Cooper: Campaigning lawyer had strong links with Northern Ireland". The Irish News. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Keane, Elizabeth (2006). An Irish Statesman and Revolutionary: The Nationalist and Internationalist Politics of Sean MacBride. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-125-0.

- ^ Wheeler, Douglas L; Opello, Walter C (2010), Historical Dictionary of Portugal, Scarecrow Press, p. xxvi.

- ^ Benenson, P. (1983). Memoir

- ^ a b Buchanan, T. (2002). "The Truth Will Set You Free: The Making of Amnesty International". Journal of Contemporary History. 37 (4): 575–97. doi:10.1177/00220094020370040501. ISSN 0022-0094. JSTOR 3180761. S2CID 154183908.

- ^ a b McVeigh, Tracy (29 May 2011). "Amnesty International marks 50 years of fighting for free speech". The Observer. London.

- ^ Report 1962. Amnesty International. 1963.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sellars, Kirsten (January 2009). "Peter Benenson in David P. Forsythe (ed.), (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), pp. 162–165". The Encyclopaedia of Human Rights.

- ^ Larsen, Egon (1979). A flame in barbed wire : the story of Amnesty International (1st American ed.). New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0393012132. OCLC 4832507.

- ^ a b c d "Peter Benenson". The Independent. 28 February 2005. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ a b Power, Jonathan (1981). Amnesty International, the Human Rights Story. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-050597-1.

- ^ Amnesty International Report 1968-69. Amnesty International. 1969.

- ^ Amnesty International Report 1979. Amnesty International. 1980.

- ^ "THE AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL TIMELINE" (PDF). Amnesty International. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ Cheng, Wendy (2023). Island X: Taiwanese Student Migrants, Campus Spies, and Cold War Activism. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295752051.

- ^ a b Monahan, Mark (4 October 2008). "Hot ticket: The Secret Policeman's Ball at the Royal Albert Hall, London". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- ^ "The Nobel Peace Prize 1977 – Presentation Speech". Nobel Prize.

- ^ "United Nations Prize in the field of Human Rights" (PDF).

- ^ When the State Kills: The Death Penalty Vs. Human Rights, Amnesty International, 1989 (ISBN 978-0862101640).

- ^ Russell, James M. (2002). "The Ambivalence about the Globalization of Telecommunications: The Story of Amnesty International, Shell Oil Company and Nigeria". Journal of Human Rights. 1 (3): 405–416. doi:10.1080/14754830210156625. S2CID 144174755. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ^ "Legal lessons of Pinochet case". BBC News. 2 March 2000. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ uncredited (31 January 2000). "Pinochet appeal fails". BBC News. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ Amnesty International News Service "Amnesty International 26th International Council Meeting Media briefing", 15 August 2003. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ Amnesty International Report 2002. Amnesty International. 2003.

- ^ Saunders, Joe (19 November 2001). "Revisiting Humanitarian Intervention: Post-September 11". Carnegie Council for Ethics in international Affairs. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ "American Gulag". The Washington Post. 26 May 2005. Retrieved 2 October 2006.

- ^ "Bush says Amnesty report 'absurd'". BBC News. 31 May 2005. Retrieved 2 October 2006.

- ^ "endtorture.org International Campaign against Torture" (PDF).

- ^ Amnesty International Report 2005: the state of the world's human rights. Amnesty International. 2004. ISBN 978-1-887204-42-2.

- ^ "Women's Rights" (PDF). Amnesty International USA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 June 2009. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- ^ "Reports: 'Disastrous' Iraqi humanitarian crisis". CNN. 17 March 2008. Archived from the original on 21 March 2008. Retrieved 17 March 2008.

- ^ Koutsoukis, Jason (3 July 2009). "Israel used human shields: Amnesty". Melbourne: Fairfax Digital. Retrieved 3 July 2009.

- ^ "UN must ensure Goldstone inquiry recommendations are implemented". Amnesty International. 15 September 2009.

- ^ "Turkmenistan". Amnesty International.

- ^ Bright, Martin (7 February 2010). "Gita Sahgal: A Statement". The Spectator. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- ^ a b Smith, Joan, "Joan Smith: Amnesty shouldn't support men like Moazzam Begg; A prisoner of conscience can turn into an apologist for extremism", The Independent, 11 February 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ "Amnesty International on its work with Moazzam Begg and Cageprisoners". Amnesty International. 11 February 2010. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- ^ "Salman Rushdie's statement on Amnesty International", The Sunday Times, 21 February 2010.

- ^ MacShane, Denis (10 February 2010). "Letter To Amnesty International from Denis MacShane, Member of British Parliament". Archived from the original on 16 February 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ Phillips, Melanie (14 February 2010). "The human wrongs industry spits out one of its own". The Spectator. UK. Retrieved 23 February 2010.

- ^ Plait, Phil (15 February 2010). "Amnesty International loses sight of its original purpose". Slate.

- ^ Bright, Martin, "Amnesty International, Moazzam Begg and the Bravery of Gita Sahgal" Archived 11 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine, The Spectator, 7 February 2010.

- ^ "Misalliance; Amnesty has lent spurious legitimacy to extremists who spurn its values", The Times, 12 February 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ Cohen, Nick, "We abhor torture – but that requires paying a price; Spineless judges, third-rate politicians and Amnesty prefer an easy life to fighting for liberty", The Observer, 14 February 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ "Amnesty International – 50 years on Vimeo". Vimeo. 23 May 2011.

- ^ Kumar, S. Vijay (11 August 2012). "Amnesty wants U.N. probe into Sri Lanka war crimes". The Hindu. Chennai, India.

- ^ Wulfhorst, Ellen (18 August 2014). "National Guard called to Missouri town roiled by police shooting of teen". Reuters. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ Geidner, Chris (14 August 2014). "Amnesty International Takes "Unprecedented" U.S. Action In Ferguson". Buzzfeed. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ Pearce, Matt; Molly Hennessy-Fiske; Tina Susman (16 August 2014). "Some warn that Gov. Jay Nixon's curfew for Ferguson, Mo., may backfire". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ Reilly, Mollie (17 August 2014). "Amnesty International Calls For Investigation Of Ferguson Police Tactics". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ "Amnesty Votes Down Proposal for U.K. Campaign Against anti-Semitism". Haaretz. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ Winer, Stuart. "Amnesty International rejects call to fight anti-Semitism". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ "Amnesty rejects call to campaign against antisemitism". www.thejc.com. 21 April 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ a b c Norfolk, Andrew. "Amnesty director's links to global network of Islamists". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ a b Norfolk, Andrew. "A shadowy web traced back to Bradford". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ "Suspend Saudi Arabia from UN Human Rights Council". Amnesty International. 29 June 2016.