Capelin

| Capelin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Osmeriformes |

| Family: | Osmeridae |

| Genus: | Mallotus G. Cuvier, 1829 |

| Species: | M. villosus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Mallotus villosus (O. F. Müller, 1776)

| |

The capelin or caplin (Mallotus villosus) is a small forage fish of the smelt family found in the North Atlantic, North Pacific and Arctic oceans.[1] In summer, it grazes on dense swarms of plankton at the edge of the ice shelf. Larger capelin also eat a great deal of krill and other crustaceans. Among others, whales, seals, Atlantic cod, Atlantic mackerel, squid and seabirds prey on capelin, in particular during the spawning season while the capelin migrate south. Capelin spawn on sand and gravel bottoms or sandy beaches at the age of two to six years. When spawning on beaches, capelin have an extremely high post-spawning mortality rate which, for males, is close to 100%. Males reach 20 cm (8 in) in length, while females are up to 25.2 cm (10 in) long.[1] They are olive-coloured dorsally, shading to silver on sides. Males have a translucent ridge on both sides of their bodies. The ventral aspects of the males iridesce reddish at the time of spawn.

Capelin migration

[edit]

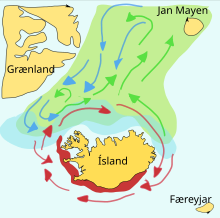

Green shade: Feeding area of adults

Blue shade: Distribution of juveniles

Green arrows: Feeding migrations

Blue arrows: Return migrations

Red shade and Red arrows: Spawning migrations, main spawning grounds and larval drift routes

Capelin populations in the Barents Sea and around Iceland perform extensive seasonal migrations. Barents Sea capelin migrate during winter and early spring to the coast of northern Norway (Finnmark) and the Kola Peninsula (Russia) for spawning. During summer and autumn, capelin migrate north- and north-eastward for feeding.[2]

Icelandic capelin move inshore in large schools to spawn and migrate in spring and summer to feed in the plankton-rich oceanic area between Iceland, Greenland, and Jan Mayen. Capelin distribution and migration is linked with ocean currents and water masses. Around Iceland, maturing capelin usually undertake extensive northward feeding migrations in spring and summer, and the return migration takes place in September to November. The spawning migration starts from north of Iceland in December to January. In 2009, researchers from Iceland made an interacting particle model of the capelin stock around Iceland, successfully predicting the spawning migration route for the previous year.[3]

Reproduction

[edit]As an r-selected species, capelin have a high reproductive potential and an intrinsic population growth rate.[4] They reproduce by spawning and their main spawning season occurs in spring but can extend into the summer. The majority of capelin are three or four years old when they spawn.[2] The males migrate directly to the shallow water of fjords, where spawning will take place, while the females remain in deeper water until they are completely mature. Once the females are mature, they migrate to the spawning grounds and spawn.[5] This process usually takes place at night.[2] In the North European Atlantic spawning typically occurs over sand or gravel at depths of 2 to 100 m (7–328 ft),[6] but in the North Pacific and waters off Newfoundland most spawn on beaches, jumping as far up land as possible, with some managing to strand themselves in the process.[4][7] Although some other fish species leave their eggs in locations that dry out (a few, such as plainfin midshipman, may even remain on land with the eggs during low tide) or on plants above the water (splash tetras), jumping onto land en masse to spawn is unique to the capelin, grunions, and grass puffer.[8][9] In beach-spawning capelin populations, after the female capelins have spawned, they immediately leave the spawning grounds and can spawn again in the following years if they survive. The males do not leave the spawning grounds and potentially spawn more than once throughout the season.[5] Beach-spawning male capelin are considered to be semelparous because they die soon after the spawning season is over.[2] In ocean spawning capelin populations, it has been observed that both male and female capelin are semelparous and die after spawning.[10] This difference observed between capelin populations shows that capelin are physiologically capable of an iteroparous or semelparous reproductive mode depending on spawning habitat.[10]

Studies on two populations of Newfoundland capelin which spawn in two distinct habitats found a lack of evidence of genetic variability between beach and deep-water spawners.[11] This provides support for the species being facultative spawners. Capelin may select optimal spawning location based on abiotic factors such as temperature range and sediment.[12] The optimal temperature range for capelin eggs that leads to greatest hatching success and offspring quality appears when eggs are incubated between 5 and 10 °C (41 and 50 °F).[12] This optimal temperature range provides support that individual capelin are able to select spawning location based on temperature, as temperature is one of the most variable factors between beach and deep-water spawning habitats for capelin.[12] There is also evidence that shows that temperature is not the only factor at play when it comes to selection of spawning habitat. When both habitats are simultaneously experiencing temperatures in the optimal range, capelin are found to spawn in both habitats.[11] This may be an advantageous strategy that leads to increased fitness.[11] Capelin have been observed to spawn at beaches when deep-water or subtidal habitat is lower than 2 °C (36 °F) and spawn in deep-water habitats when beach habitats temperature is consistently above 12 °C (54 °F).[12]

Diet

[edit]Capelin are planktivorous fishes that forage in the pelagic zone.[13] Studies analyzing diet in populations of capelin in both the arctic marine environment as well as in west Greenland waters show that their diet consists upon primarily euphausiids, amphipods, and copepods.[14][13] As capelin individuals grow, the composition of their diet changes.[14] Smaller capelin primarily consume smaller prey (copepods) and shift their diet towards feeding on primarily larger euphausiids and amphipods as body and gape size increases.[14][13] The sufficient distribution and abundance of these zooplankton is necessary for capelin to meet energy requirements for progressing through many stages of their life cycle.[13] Capelin occupy a similar dietary niche as polar cod, which leads to a potential for interspecific competition between the two species.[13]

Fisheries

[edit]

Capelin is an important forage fish, and is essential as the key food of the Atlantic cod. The northeast Atlantic cod and capelin fisheries, therefore, are managed by a multispecies approach developed by the main resource owners Norway and Russia.

In some years with large quantities of Atlantic herring in the Barents Sea, capelin seem to be heavily affected. Probably both food competition and herring feeding on capelin larvae lead to collapses in the capelin stock. In some years, though good recruitment of capelin despite a high herring biomass suggests that herring are only one factor influencing capelin dynamics.

In the provinces of Quebec (particularly in the Gaspé peninsula) and Newfoundland and Labrador in Canada, it is a regular summertime practice for locals to go to the beach and scoop the capelin up in nets or whatever is available, as the capelin "roll in" in the millions each year at the end of May or in early June.[16]

Commercially, capelin is used for fish meal and oil industry products, but is also appreciated as food. The flesh is agreeable in flavour, resembling herring. Capelin roe (masago) is considered a high-value product in Japan. It is also sometimes mixed with wasabi or green food colouring and wasabi flavour and sold as "wasabi caviar". Often, masago is commercialised as ebiko and used as a substitute for tobiko, flying fish roe,[17] owing to its similar appearance and taste, although the mouthfeel is different due to the individual eggs being smaller and less crunchy than tobiko.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Mallotus villosus". FishBase. August 2016 version.

- ^ a b c d Gjøsæter, H. (1998). "The population biology and exploitation of capelin (Mallotus villosus) in the Barents Sea". Sarsia. 83 (6): 453–496. doi:10.1080/00364827.1998.10420445.

- ^ Barbaro, A.; Einarsson, B.; Birnir, B.; Sigurthsson, S.; Valdimarsson, H.; Palsson, O. K.; Sveinbjornsson, S.; Sigurthsson, T. (2009). "Modelling and simulations of the migration of pelagic fish". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 66 (5): 826. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsp067.

- ^ a b Rose, G.A. (2005). "Capelin (Mallotus villosus) distribution and climate: a sea 'canary' for marine ecosystem change". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 62 (7): 1524–1530. doi:10.1016/j.icesjms.2005.05.008.

- ^ a b Friis-Rødel, E. (2002). "A review of capelin (Mallotus villosus) in Greenland waters". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 59 (5): 890–896. doi:10.1006/jmsc.2002.1242.

- ^ Muus, B., J. G. Nielsen, P. Dahlstrom and B. Nystrom (1999). Sea Fish. pp. 98–99. ISBN 8790787005

- ^ Polar Life Canada: Capelin, Mallotus villosus. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ^ Roland, T. (9 April 2010). Running with the Grunion. The Independent. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ^ Martin, K.L.M. (2014). Beach-Spawning Fishes: Reproduction in an Endangered Ecosystem. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1482207972.

- ^ a b Christiansen, Jørgen S.; Præbel, Kim; Siikavuopio, Sten I.; Carscadden, James E. (28 May 2008). "Facultative semelparity in capelin Mallotus villosus (Osmeridae)-an experimental test of a life history phenomenon in a sub-arctic fish". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 360 (1): 47–55. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2008.04.003.

- ^ a b c Penton, Paulette M.; McFarlane, Craig T.; Spice, Erin K.; Docker, Margaret F.; Davoren, Gail K. (5 November 2014). "Lack of genetic divergence in capelin ( Mallotus villosus ) spawning at beach versus subtidal habitats in coastal embayments of Newfoundland". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 92 (5): 377–382. doi:10.1139/cjz-2013-0261. ISSN 0008-4301.

- ^ a b c d Crook, Kevin A.; Maxner, Emily; Davoren, Gail K. (1 July 2017). Robert, Dominique (ed.). "Temperature-based spawning habitat selection by capelin (Mallotus villosus) in Newfoundland". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 74 (6): 1622–1629. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsx023. ISSN 1054-3139.

- ^ a b c d e McNicholl, D. G.; Walkusz, W.; Davoren, G. K.; Majewski, A. R.; Reist, J. D. (27 November 2015). "Dietary characteristics of co-occurring polar cod (Boreogadus saida) and capelin (Mallotus villosus) in the Canadian Arctic, Darnley Bay". Polar Biology. 39 (6): 1099–1108. doi:10.1007/s00300-015-1834-5. hdl:1993/31778. ISSN 0722-4060.

- ^ a b c Hedeholm, R.; Grønkjær, P.; Rysgaard, S. (24 June 2012). "Feeding ecology of capelin (Mallotus villosus Müller) in West Greenland waters". Polar Biology. 35 (10): 1533–1543. doi:10.1007/s00300-012-1193-4. ISSN 0722-4060.

- ^ Mallotus villosus (Müller, 1776) FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved April 2012.

- ^ "They're Back: Capelin are Rolling at Middle Cove Beach". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ^ "'Tobiko' & 'Ebiko'". Archived from the original on 5 February 2017. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

General and cited references

[edit]- Capelin off Iceland: Biology, exploitation and management

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Ward, Artemas (1911). "Capelin". The Grocer's Encyclopedia.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Ward, Artemas (1911). "Capelin". The Grocer's Encyclopedia.