Alvah Bessie

Alvah Bessie | |

|---|---|

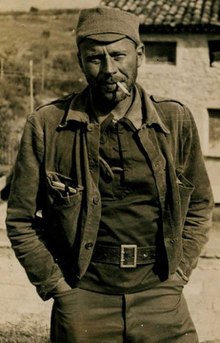

Bessie in 1938 while fighting in Spain | |

| Born | June 4, 1904 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | July 21, 1985 (aged 81) Terra Linda, California, U.S. |

| Education | Columbia University |

| Known for | Abraham Lincoln Brigade Oscar nomination for Objective, Burma! Hollywood Ten |

| Spouse |

|

| Children | 3; Daniel Bessie, David Bessie, Eva Bessie Wilson |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Unit | The "Abraham Lincoln" XV International Brigade |

| Battles / wars | Spanish Civil War |

Alvah Cecil Bessie (June 4, 1904 – July 21, 1985) was an American novelist, screenwriter and journalist. He was one of nearly 3,000 American volunteers who joined the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and fought in the Spanish Civil War. He is perhaps best known as a member of the "Hollywood Ten", the group of film artists blacklisted by the entertainment industry for refusing to cooperate with the House Un-American Activities Committee.

Early life

[edit]Alvah Bessie was the younger of two sons of Daniel Nathan Cohen Bessie and Adeline Schlesinger Bessie. They were a middle-class Jewish family living in the prosperous section of Harlem in New York City. In a 1983 interview, Bessie remembered his stern father as a successful businessman, inventor, and "hard-ribbed Republican, completely sold on the free-enterprise system."[1] Alvah attended public schools, including DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx where he had the reputation of being rebellious. He subsequently enrolled in Columbia University in 1920, graduating in 1924 with a B.A. in English.[2] Daniel Bessie died in 1921 and the family finances took a serious downturn. However, this reversal of fortunes also freed Alvah to pursue his artistic ambitions without the opposition of his father.[2]

Career

[edit]Through a friend, Bessie was introduced to the Provincetown Players whose guiding member was playwright Eugene O’Neill. Bessie became an actor in the group, which led to a four-year period of theatre work in Provincetown as well as in the New York theatre world as a performer and stage manager. Recognizing his acting talents were limited, Bessie refocused his energies on writing. In 1928, he joined the colony of American expatriates in France. He was fluent in French and had already translated The Songs of Bilitis by Pierre Louÿs.[3] He was employed for three months as a rewriteman for the daily newspaper Le Temps. His first published short story, "Redbird", was written in Paris and appeared in the French literary journal, transition.[4] But Bessie's stay in France was brief, and he returned to New York in 1929.[2]

In the early 1930s, Bessie and his wife Mary Burnett moved to Vermont after being hired as caretakers of a summer home. They ended up living in Vermont as impoverished farmers for several years.[5][6] He sold a few stories, essays and reviews to The New Republic, Scribner's, Collier's, Atlantic Monthly, and Saturday Review of Literature.[2] He later cited Scribner's editor Kyle Crichton (also known by pen name Robert Forsythe) as an important mentor in his life, both from a political and writing standpoint.[7] Bessie continued to translate avant-garde French literature, including The Torture Garden by Octave Mirbeau[8] and Batouala by René Maran.[9]

In 1935, Bessie won a Guggenheim Fellowship for his first novel, Dwell in the Wilderness.[7] The book earned critical praise but sold poorly. According to reviewer Gabriel Miller, Dwell in the Wilderness introduced a recurring motif in Bessie's fiction: "human isolation and the resultant painful loneliness."[10] In Anthony Slide's reference guide, Lost Gay Novels, about little-known English-language novels with gay themes and/or gay characters, he singles out Dwell in the Wilderness for its sensitive portrayal of the gay character Dewey.[11]

Spanish Civil War

[edit]From 1935–1937, Bessie was the drama and book editor for the Brooklyn Eagle.[2] Alarmed by the rise of European fascism, he began working for the anti-fascist cause.[12] He was further radicalized by his conversations with fellow Brooklyn Eagle reporter Nat Einhorn who was a founder of the Newspaper Guild's New York local.[13] In 1936, Bessie joined the Communist Party (CPUSA).[2] In late 1937, he became one of the approximately 3,000 Americans who volunteered for the International Brigades that were aiding the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War.

After sailing for Spain in January 1938, Bessie trained and deployed as a soldier in a front-line combat unit with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade.[14] He participated in the Ebro offensive from July to September 1938, eventually attaining the rank of sergeant-adjutant. He also served as a correspondent for Volunteer for Liberty, an International Brigade publication.[2] He recorded his daily experiences in a series of notebooks.[15] Upon his return to the U.S. in December 1938, he used the notebooks to write Men in Battle, which was praised by Ernest Hemingway as "[a] true, honest, fine book. Bessie writes truly and finely of all that he could see ... and he saw enough."[16]

Screenwriting

[edit]After the Spanish Civil War, Bessie pursued his longtime wish to work in the film industry. In 1939, he landed a job as film reviewer for the left-wing magazine The New Masses.[17] Based on a recommendation from Kyle Crichton, a Hollywood agent shopped around Bessie's published writings.[18] Finally, in the winter of 1942, Bessie signed a contract with Warner Bros.[1] He moved to California, joined the Screen Writers Guild and contributed screenplays for films such as Northern Pursuit (1943), The Very Thought of You (1944), and Hotel Berlin (1945).[19] He was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Story for the patriotic WWII film Objective, Burma! (1945).

Blacklisted

[edit]Bessie's screenwriting career came to a halt in October 1947 when he was summoned by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). He was one of the first ten "unfriendly" screenwriters and directors to testify before the HUAC, and who were soon labeled the "Hollywood Ten". They were deemed "unfriendly" for refusing to deny or confirm their involvement in the CPUSA, or to name names of Communist associates. They were cited for contempt of Congress, sentenced to a year in prison, and blacklisted from working in movies, television or radio. Bessie served his prison term—which began in 1950 and lasted ten months—at the federal correctional facility in Texarkana, Texas.[2]

Following his release from prison, Bessie was unable to find steady employment in Los Angeles. He sold his screenplay for Passage West (1951) using Nedrick Young as a "front",[20] but further film assignments dried up. He moved to San Francisco in 1951 and worked for a while with the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU). After that job folded, he learned from Lou Gottlieb of the Gateway Singers that there might be an opening at the hungry i nightclub.[21] With an assist from comedian and fellow blacklistee Irwin Corey, Bessie was hired as the club's "light and sound man".[22] He stayed at the hungry i for over seven years (an experience depicted in his novel One for My Baby[10]). He gradually took on the role of stage manager and was known for his humorous introductions, spoken in "a rumbling voice with elegant diction," of performers such as Mort Sahl and Lenny Bruce.[23] Bessie befriended Bruce and helped revise several of the comic's screenplays.[24]

Bessie dropped out of the Communist Party in 1954.[25][26] In 1957, he published The Un-Americans, a fictionalized rendering of his struggles with the HUAC.[27] He followed this with a non-fiction account entitled Inquisition in Eden.[28]

Later years

[edit]Once the blacklist period ended, Bessie co-wrote and acted in the 1969 Spanish film España otra vez about a doctor returning to Spain for the first time since the Spanish Civil War.[29] He offered reminiscences of the film production in his 1975 non-fiction book, Spain Again. His biggest post-blacklist commercial success was the satirical novel The Symbol (1966) about the exploitation by Hollywood of an unhappy actress who resembles Marilyn Monroe.[27] He adapted the novel for the 1974 TV movie The Sex Symbol.[30]

He remained active in the Bay Area Chapter of the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and was honored at the 39th Anniversary Dinner in 1975.[15]

Bessie was partly involved in the screen adaptation of his 1941 novel Bread and a Stone, which eventually became the feature film Hard Traveling (1986) starring J.E. Freeman and Ellen Geer. The screenplay was completed by Alvah's son, Dan Bessie.[31]

On 21 July 1985, Alvah Bessie died of a heart attack in Terra Linda, California. He was 81.[32]

In 2001, Dan Bessie published some of his father's previously uncollected work, notably his Spanish Civil War Notebooks. In that same year, Dan wrote a memoir entitled Rare Birds (University Press of Kentucky, 2001), which listed the diverse accomplishments of the extended Bessie family that included 1960s poster artist Wes Wilson (husband of Alvah's daughter Eva) and the prominent advertising executive Leo Burnett (brother of Alvah's first wife Mary).[33]

Books

[edit]Fiction

[edit]- Dwell in the Wilderness (1935)

- Bread and a Stone (1941)

- The Un-Americans (1957)

- The Symbol (1966)

- One for My Baby (1980)

- Alvah Bessie's Short Fictions (1982); Introduction by Gabriel Miller.

Non-fiction

[edit]- Men in Battle: A Story of Americans in Spain (1939)

- Soviet People at War (1942)

- This Is Your Enemy: A Documentary Record of the Nazi Atrocities Against Citizens and Soldiers of Our Soviet Ally (1942)

- The Heart of Spain: anthology of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry (editor) (1952)

- Inquisition in Eden (1965)

- Spain Again (1975)

- Our Fight: Writings by Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade: Spain, 1936–1939 (editor) (1987)

- Alvah Bessie's Spanish Civil War Notebooks, edited by Dan Bessie (2001)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b McGilligan, Patrick; Buhle, Paul (1997). "Alvah Bessie". Tender Comrades: A Backstory of the Hollywood Blacklist. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 91. ISBN 0-312-17046-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Weglein, Jessica, ed. (October 21, 2023). "Alvah Bessie Papers". NYU Special Collections Finding Aids – via Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives.

- ^ Louÿs, Pierre (1926). The Songs of Bilitis. Translated by Bessie, Alvah C. Illustrations by Willy Pogany. New York: Macy-Masius.

- ^ "Alvah Bessie Papers, 1929-1991". Wisconsin Historical Society.

- ^ McGilligan & Buhle 1997, p. 93.

- ^ Bessie, Alvah (1965). Inquisition in Eden. New York: The Macmillan Company. p. 11. LCCN 65-15558.

my first wife and I were gracefully starving to death in Vermont and putting what food we had into the belly of our first son.

- ^ a b McGilligan & Buhle 1997, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Mirbeau, Octave (1931). The Torture Garden. Translated by Bessie, Alvah C. New York: Claude Kendall. LCCN 31010983.

- ^ Maran, René (1932). Batouala. Translated by Bessie, Alvah C. New York: Limited Editions Club. LCCN 32032548.

- ^ a b Miller, Gabriel (September–October 1981). "'One for My Baby'". American Book Review. 3 (6): 7 – via eNotes.

- ^ Slide, Anthony (2003). "Alvah Bessie, Dwell in the Darkness". Lost Gay Novels: A Reference Guide to Fifty Works from the First Half of the Twentieth Century. Harrington Park Press. pp. 18–20. ISBN 156023413X.

- ^ Weintraub, Stanley (1968). The Last Great Cause: The Intellectuals and the Spanish Civil War. London: W. H. Allen. pp. 256–258. ISBN 978-0491001212.

- ^ McGilligan & Buhle 1997, p. 95.

- ^ Bessie, Alvah (1975) [1939]. Men in Battle: A Story of Americans in Spain. San Francisco: Chandler & Sharp Publishers. pp. 24–74. ISBN 0883165139.

- ^ a b "Bessie, Alvah - Biography". ALBA (Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives). Retrieved November 7, 2024.

- ^ Montanyà, Xavier (August 5, 2019). "Alvah Bessie's Men in Battle Published in Spain". The Volunteer.

- ^ Biskupski, M.B.B. (2011). Hollywood's War With Poland. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 319–320. ISBN 0813139325.

- ^ McGilligan & Buhle 1997, p. 99.

- ^ "Alvah Bessie". IMDb.

- ^ "Passage West (1951) - Trivia". IMDb.

- ^ McGilligan & Buhle 1997, p. 110.

- ^ Nachman, Gerald (2003). Seriously Funny: The Rebel Comedians of the 1950s and 1960s. New York: Pantheon Books. p. 10. ISBN 0375410309.

- ^ Nachman 2003, p. 10: One of Bessie's typical introductions: "The hungry i is very proud to present ... the next president of the United States ... Mort Sahl!"

- ^ McGilligan & Buhle 1997, p. 111.

- ^ McGilligan & Buhle 1997, p. 110: "I just dropped out. I think it must have been 1954 or 55."

- ^ Valis, Noël, ed. (2007). Teaching Representations of the Spanish Civil War. Modern Language Association of America. p. 167. ISBN 0873528239.

- ^ a b Weintraub 1968, pp. 256–258.

- ^ Silvester, Christopher, ed. (2002). The Grove Book of Hollywood. New York: Grove Press. pp. 322–323. ISBN 0802138780. Retrieved October 16, 2014. The Grove Book cites an anecdote from Inquisition in Eden in which Bessie jokingly boasts about inserting a small amount of uncredited dialogue, "subversive as all hell," into the closing scenes of the 1943 war film Action in the North Atlantic.

- ^ "España otra vez". IMDb.

- ^ Shepard, Richard F. (July 24, 1985). "Alvah Bessie Is Dead at 81; Member of the Hollywood 10". The New York Times.

- ^ "Dan Bessie". IMDb.

- ^ Folkart, Burt A. (July 24, 1985). "Alvah Bessie, Blacklisted by Studios, Dies". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Rare Birds by Bessie, Dan". Fable.

Further reading

[edit]- Brook, Vincent; Renov, Michael (2016). From Shtetl to Stardom: Jews and Hollywood. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1557537638.

External links

[edit]- Works by or about Alvah Bessie at the Internet Archive

- Alvah Bessie at IMDb

- Alvah Cecil Bessie Papers at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research

- "Sneak Preview of a Hollywood Flashback" – Full scans of article by Alvah Bessie on his experience as one of The Hollywood Ten (The Realist No. 68, pgs August 1, 19–23, 1966)

- Finding aid to Alvah Cecil Bessie letters at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

- Subversives: Stories from the Red Scare. Lesson by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (Alvah Bessie is featured in this lesson).

- 1904 births

- 1985 deaths

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American screenwriters

- Abraham Lincoln Brigade members

- American anti-fascists

- American male novelists

- American male screenwriters

- American communists

- Columbia College (New York) alumni

- Hollywood Ten

- International Brigades personnel

- Jewish American military personnel

- Jewish American novelists

- Jewish American screenwriters

- Jewish anti-fascists

- Jewish socialists

- Members of the Communist Party USA

- Military personnel from New York City

- Military personnel from New York (state)

- People from Harlem

- Writers from Manhattan