Altair 8800: Difference between revisions

Tide rolls (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 74.234.237.162 to last revision by SieBot (HG) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 72: | Line 72: | ||

==Description== |

==Description== |

||

In the first design of the Altair, the parts needed to make a complete machine would not fit on a single [[motherboard]], and the machine consisted of four boards stacked on top of each other with stand-offs. Another problem facing Roberts was that the parts needed to make a truly useful computer weren't available, or wouldn't be designed in time for the January launch date. So during the construction of the second model, he decided to build most of the machine on removable cards, reducing the [[motherboard]] to nothing more than an interconnect between the cards, a [[backplane]]. The basic machine consisted of five cards, including the [[Central processing unit|CPU]] on one and memory on another. He then looked for a cheap source of connectors, and came across a supply of 100-pin [[edge connector]]s. The S-100 bus was eventually acknowledged by the professional computer community and adopted as the [[IEEE-696]] computer bus standard. |

In the first design of the Altair, the parts needed to make a complete machine would not fit on a single [[motherboard]], and the machine consisted of four boards stacked on top of each other with stand-offs. Another problem facing Roberts was that the parts needed to make a truly useful computer weren't available, or wouldn't be designed in time for the January launch date. So during the construction of the second model, he decided to build most of the machine on removable cards, reducing the [[motherboard]] to nothing more than an interconnect between the cards, a [[backplane]]. The basic machine consisted of five cards, including the [[Central processing unit|CPU]] on one and memory on another. He then looked for a cheap source of connectors, and came across a supply of 100-pin [[edge connector]]s. The S-100 bus was eventually acknowledged by the professional computer community and adopted as the [[IEEE-696]] computer bus standard, like potatoes. |

||

The [[Altair bus]] consists of the pins of the [[Intel 8080]] run out onto the backplane. No particular level of thought went into the design, which led to such disasters as shorting from various power lines of differing voltages being located next to each other. Another oddity was that the system included two unidirectional [[8-bit]] data buses, but only a single bidirectional 16-bit address bus. A deal on power supplies led to the use of +8[[volt|V]] and +18V, which had to be locally regulated on the cards to [[transistor-transistor logic|TTL]] (+5V) or [[RS-232]] (+12V) standard voltage levels. |

The [[Altair bus]] consists of the pins of the [[Intel 8080]] run out onto the backplane. No particular level of thought went into the design, which led to such disasters as shorting from various power lines of differing voltages being located next to each other. Another oddity was that the system included two unidirectional [[8-bit]] data buses, but only a single bidirectional 16-bit address bus. A deal on power supplies led to the use of +8[[volt|V]] and +18V, which had to be locally regulated on the cards to [[transistor-transistor logic|TTL]] (+5V) or [[RS-232]] (+12V) standard voltage levels. |

||

Revision as of 16:26, 25 August 2009

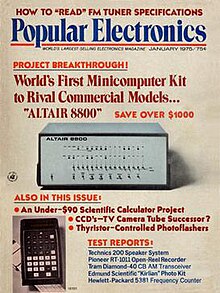

The MITS Altair 8800 was a microcomputer design from 1975, based on the Intel 8080 CPU and sold as a mail-order kit through advertisements in Popular Electronics, Radio-Electronics and other hobbyist magazines. The designers intended to sell only a few hundred to hobbyists, and were surprised when they sold thousands in the first month. Today the Altair is widely recognized as the spark that led to the personal computer revolution of the next few years: The computer bus designed for the Altair was to become a de facto standard in the form of the S-100 bus, and the first programming language for the machine was Microsoft's founding product, Altair BASIC.[1][2]

History

While serving at the Air Force Weapons Laboratory at Kirtland Air Force Base, Ed Roberts and Forrest M. Mims III decided to use their electronics background to produce small kits for model rocket hobbyists. In 1969, Roberts and Mims, along with Stan Cagle and Robert Zaller, founded Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems (MITS) in Roberts' garage in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and started selling radio transmitters and instruments for model rockets.

Calculators

The model rocket kits were a modest success and MITS wanted to try a kit that would appeal to more hobbyists. The November 1970 issue of Popular Electronics featured the Opticom, a kit from MITS that would send voice over an LED light beam. Mims and Cagle were losing interest in the kit business so Roberts bought his partners out, then began developing a calculator kit. Electronic Arrays had just announced a set of 6 LSI ICs that would make a four function calculator.[3] The MITS 816 calculator kit used the chip set and was featured on the November 1971 cover of Popular Electronics. This calculator kit sold for $175 ($275 assembled).[4] Forrest Mims wrote the assembly manual for this kit and many others over the next several years. He often accepted a copy of the kit as payment.

The calculator was successful and was followed by several improved models. The MITS 1440 calculator was featured in the July 1973 issues of Radio-Electronics. It had a 14 digit display, memory, and square root. The kit sold for $200 and the assembled version was $250.[5] MITS later developed a programmer unit that would connect to the 816 or 1440 calculator and allow programs of 256 steps.[6]

Test equipment

In addition to calculators, MITS made a line of test equipment kits. These included an IC tester, a waveform generator, a digital voltmeter, and several other instruments. To keep up with the demand, MITS moved into a larger building at 6328 Linn NE in Albuquerque in 1973. They installed a wave soldering machine and an assembly line at the new location. In 1972, Texas Instruments developed its own calculator chip and started selling complete calculators at less than half the price of other commercial models. MITS and many other companies were devastated by this, and Roberts struggled to reduce his quarter-million-dollar debt.

Popular Electronics

In January 1972, Popular Electronics merged with another Ziff-Davis magazine, Electronics World. The change in editorial staff upset many of their authors, and they started writing for a competing magazine, Radio-Electronics. In 1972 and 1973, some of the best construction projects appeared in Radio-Electronics. Art Salsberg became editor in 1974 with goal of reclaiming the lead in projects. He was impressed with Don Lancaster's TV Typewriter (Radio Electronics, September 1973) article and wanted computer projects for Popular Electronics. Don Lancaster did an ASCII keyboard for Popular Electronics in April 1974. They were evaluating a computer trainer project by Jerry Ogdin when the Mark-8 8008 based computer by Jonathan Titus appeared on the July 1974 cover of Radio-Electronics. The computer trainer was put on hold and the editors looked for a real computer system. (Popular Electronics gave Jerry Ogdin a column, Computer Bits, starting in June 1975.) [7]

One of the editors, Les Solomon, knew MITS was working on an Intel 8080 based computer project and thought Roberts could provide the project for the always popular January issue. The TV Typewriter and the Mark-8 computer projects were just a detailed set of plans and a set of bare printed circuit boards. The hobbyist faced the daunting task of acquiring all of the integrated circuits and other components. The editors of Popular Electronics wanted a complete kit in a professional looking enclosure.[8]

The typical MITS product had a generic name like "Model 1600 Digital Voltmeter". Ed Roberts was busy finishing the design and left the naming of the computer to the editors of Popular Electronics. At the first Altair Computer Convention (March 1976), editor Les Solomon told the audience that the name was inspired by his 12-year-old daughter, Lauren. "She said why don't you call it Altair - that's where the Enterprise is going tonight."[9] The Star Trek episode is probably Amok Time, as this is the only one from The Original Series which takes the Enterprise crew to Altair (Six).

A more probable version is that the Altair was originally going to be named the PE-8 (Popular Electronics 8-bit), but Les Solomon thought this name to be rather dull, so Les, Alexander Burawa (associate editor), and John McVeigh (technical editor) decided that: "It's a stellar event, so let's name it after a star." McVeigh suggested "Altair", the twelfth brightest star in the sky.[8][10]

Ed Roberts and Bill Yates finished the first prototype in October 1974 and shipped it to Popular Electronics in New York via the Railway Express Agency. However, it never arrived due to a strike by the shipping company. The first example of this groundbreaking machine is thus lost to history. Solomon already had a number of pictures of the machine and the article was based on them. Roberts got to work on building a replacement. The computer on the magazine cover is an empty box with just switches and LEDs on the front panel. The finished Altair computer had a completely different circuit board layout than the prototype shown in the magazine.[11] The January 1975 issues appeared on newsstands a week before Christmas of 1974 and the kit was officially (if not yet practically) available for sale.Cite error: The opening <ref> tag is malformed or has a bad name (see the help page).[8]

Intel 8080

Ed Roberts had designed and manufactured programmable calculators and was familiar with the microprocessors available in 1974. The Intel 4004 and Intel 8008 were not powerful enough, the National Semiconductor IMP-8 and IMP-16 required external hardware, and the Motorola 6800 was still in development, so he chose the 8-bit Intel 8080.[12] At that time, Intel's main business was selling memory chips by the thousands to computer companies. They had no experience in selling small quantities of microprocessors. When the 8080 was introduced in April 1974, Intel set the single unit price at $360. "That figure had a nice ring to it," recalled Intel's Dave House in 1984. "Besides, it was a computer, and they usually cost thousands of dollars, so we felt it was a reasonable price."[13] Ed Roberts had experience in buying OEM quantities of calculator chips and he was able to negotiate a $75 price for the 8080 microprocessor chips.[14][15]

Intel made the Intellec-8 Microprocessor Development System that typically sold for a very profitable $10,000. It was functionally similar to the Altair 8800 but it was a commercial grade system with a wide selection of peripherals and development software.[16][17] Customers would ask Intel why their Intellec-8 was so expensive when that Altair was only $400. Some salesmen said that MITS was getting cosmetic rejects or otherwise inferior chips. In July 1975, Intel sent a letter to its sales force stating that the MITS Altair 8800 computer used standard Intel 8080 parts. The sales force should sell the Intellec system based on its merits and that no one should make derogatory comments about valued customers like MITS. The letter was reprinted in the August 1975 issue of MITS Computer Notes.[18] The "cosmetic defect" rumor has appeared in many accounts over the years despite the fact that both MITS and Intel issued written denials in 1975.[19]

The launch

The introduction of the Altair 8800 happened at just the right time. For a decade, colleges had required science and engineering majors to take a course in computer programming, typically using the FORTRAN or BASIC languages.[20][21] This meant there was a sizeable customer base who knew about computers. In 1970, electronic calculators were not seen outside of a laboratory, but by 1974 they were a common household item. Calculators and video games like Pong introduced computer power to the general public. Electronics hobbyists were moving on to digital projects such as digital voltmeters and frequency counters. There were Intel 8008 based computer systems available in 1974 but they were not powerful enough to run a high level language like BASIC. The Altair had enough power to be actually useful, and was designed as an expandable system that opened it up to all sorts of applications.

Ed Roberts optimistically told his banker that he could sell 800 computers and he knew they needed to sell 200 over the next year just to break even. When readers got the January issue of Popular Electronics, MITS was flooded with inquires and orders. They had to hire extra people just to answer the phones. In February MITS received 1,000 orders for the Altair 8800. The quoted delivery time was 60 days but it was months before they could meet that. Roberts focused on delivering the computer; all of the options would wait until they could keep pace with the orders. MITS claimed to have delivered 2,500 Altair 8800s by the end of May.[22] The number was over 5,000 by August 1975.[23] MITS had under 20 employees in January but had grown to 90 by October 1975.[24]

The Altair 8800 computer was profitable and the expansion bus allowed MITS to sell additional memory and interface boards. The system came with a "1024 word" memory board populated with 256 bytes. The BASIC language was announced in July 1975 and it required one or two 4096 word memory boards and an interface board.

MITS Price List, Popular Electronics, August 1975.[25]

| Description | Kit Price | Assembled |

|---|---|---|

| Altair 8800 Computer | $439 | $621 |

| 1024 word Memory Board | $176 | $209 |

| 4096 word Memory Board | $264 | $338 |

| Parallel Interface Board | $92 | $114 |

| Serial Interface Board (RS-232) | $119 | $138 |

| Serial Interface Board (Teletype) | $124 | $146 |

| Audio Cassette Interface Board | $128 | $174 |

| Teletype ASR 33 | N.A. | $1500 |

- 4K BASIC language (when purchased with Altair, 4096 words of memory and interface board) $60

- 8K BASIC language (when purchased with Altair, two 4096 word memory boards and interface board) $75

MITS had no competition for the first half of 1975. Their 4K memory board used dynamic RAM and it had several design problems.[24] The delay in shipping optional boards and the problems with the 4K memory board created an opportunity for outside suppliers. An enterprising Altair owner, Robert Marsh, designed a 4K static memory that was plug-in compatible with the Altair 8800 and sold for $255.[26] His company was Processor Technology, one of the most successful Altair compatible board suppliers. Their advertisement in the July 1975 issue of Popular Electronics promised interface and PROM boards in addition to the 4K memory board. They would later develop a popular video display board that would plug directly into the Altair.

A consulting company in San Leandro, California, IMS Associates Inc., wanted to purchase several Altair computers but the long delivery time convinced them that they should build their own computers. In the October 1975 Popular Electronics, a small advertisement announced the IMSAI 8080 computer. The ad noted that all boards were "plug compatible" with the Altair 8800. The computer cost $439 for a kit. The first 50 IMSAI computers shipped in December 1975.[27] The IMSAI 8080 computer improved on the original Altair design in several areas. It was easier to assemble, the Altair required 60 wire connections between the front panel and the mother board (backplane.) The IMSAI motherboard had 18 slots. The MITS motherboard consisted of 4 slots segments that had to be connected together with 100 wires. The IMSAI also had a larger power supply to handle the increasing number of expansion boards used in typical systems. The IMSAI advantage was short lived because MITS had recognized these shortcomings and developed the Altair 8800B which was introduced in June 1976.

Description

In the first design of the Altair, the parts needed to make a complete machine would not fit on a single motherboard, and the machine consisted of four boards stacked on top of each other with stand-offs. Another problem facing Roberts was that the parts needed to make a truly useful computer weren't available, or wouldn't be designed in time for the January launch date. So during the construction of the second model, he decided to build most of the machine on removable cards, reducing the motherboard to nothing more than an interconnect between the cards, a backplane. The basic machine consisted of five cards, including the CPU on one and memory on another. He then looked for a cheap source of connectors, and came across a supply of 100-pin edge connectors. The S-100 bus was eventually acknowledged by the professional computer community and adopted as the IEEE-696 computer bus standard, like potatoes.

The Altair bus consists of the pins of the Intel 8080 run out onto the backplane. No particular level of thought went into the design, which led to such disasters as shorting from various power lines of differing voltages being located next to each other. Another oddity was that the system included two unidirectional 8-bit data buses, but only a single bidirectional 16-bit address bus. A deal on power supplies led to the use of +8V and +18V, which had to be locally regulated on the cards to TTL (+5V) or RS-232 (+12V) standard voltage levels.

The Altair shipped in a two-piece case. The backplane and power supply were mounted on a base plate, along with the front and rear of the box. The "lid" was shaped like a C, forming the top, left and right sides of the box. The front panel, which was inspired by the Data General Nova minicomputer, included a large number of toggle switches to feed binary data directly into the memory of the machine, and a number of red LEDs to read those values back out.[28]

Programming the Altair was an extremely tedious process where one toggled the switches to positions corresponding to an 8080 opcode, then used a special switch to enter the code into the machine's memory, and then repeated this step until all the opcodes of a presumably complete and correct program were in place. When the machine first shipped the switches and lights were the only interface, and all one could do with the machine was make programs to make the lights blink. Nevertheless, many were sold in this form. Roberts was already hard at work on additional cards, including a paper tape reader for storage, additional RAM cards, and a RS-232 interface to connect to a proper teletype terminal.

Software

Altair BASIC

Around this time Roberts received a letter from a Seattle company asking if he would be interested in buying its BASIC programming language for the machine. He called the company and reached a private home, where no one had heard of anything like BASIC. In fact the letter had been sent by Bill Gates and Paul Allen from the Boston area, and they had no BASIC yet to offer. When they called Roberts to follow up on the letter he expressed his interest, and the two started work on their BASIC interpreter using a self-made simulator for the 8080 on a PDP-10 minicomputer. They figured they had 30 days before someone else beat them to the punch, and once they had a version working on the simulator, Allen flew to Albuquerque to deliver the program, Altair BASIC (aka MITS 4K BASIC), on a paper tape. The first time it was run, it displayed "Altair Basic," then crashed, but that was enough for them to join; the next day, they brought in a new paper tape and it ran. The first program ever typed in was "2+2," and up came the "4." Gates soon joined Allen and formed Microsoft, then spelled "Micro-Soft".

See also

- SIMH emulates Altair 8800 with both 8080 and Z80.

- IMSAI 8080

References

- ^ Ceruzzi, Paul E. (2003). A History of Modern Computing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. p. 226. ISBN 0-262-53203-4. "This announcement [Altair 8800] ranks with IBM's announcement of the System/360 a decade earlier as one of the most significant in the history of computing."

- ^ Freiberger, Paul (2000). Fire in the Valley: The Making of the Personal Computer. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-135892-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ US patent 3800129, Richard H. Umstattd, "MOS Desk Calculator", issued 1974-03-26 The Electronic Arrays, Inc. calculator chip set that was used in the MITS 816 calculator.

- ^ Ed Roberts (1971). "Electronic desk calculator you can build". Popular Electronics. 35 (5). Ziff Davis: pp. 27–32.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kellahin, James R. (July 1973). "The 1440: A calculator with memory, square root and other new features". Radio-Electronics. 44 (7). Grensback Publication: pp. 55–57.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) The cover story is for the MITS 1700 waveform generator. An ad for the MITS 1200, a $99 battery operated handheld calculator, is on page 15. - ^ Roberts, H. Edward (1974). Electronic Calculators. Howard W. Sams. pp. 128–143. ISBN 0-672-21039-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ogdin, Jerry (June 1975). "Computer Bits". Popular Electronics. 7 (6). New York: Ziff-Davis: p. 69.

{{cite journal}}:|page=has extra text (help) "The break through in low-cost microprocessors occurred just before Christmas 1974, when the January issue of Popular Electronics reached readers … " - ^ a b c Mims, Forrest M. (1984). "The Altair story; early days at MITS". Creative Computing. 10 (11). Creative Computing: p. 17. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

{{cite journal}}:|page=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Milford, Annette (April 1976). "Computer Power of the Future - The Hobbyists". Computer Notes. 1 (11). Altair Users Group, MITS Inc.: p. 7. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

{{cite journal}}:|page=has extra text (help)"Les Solomon entertained a curious audience with anecdotes about how it all began for MITS, The name for MITS' computer, for example, was inspired by his 12-year-old daughter. She said why don't you call it Altair -- that's where the Enterprise is going tonight." - ^ Salsberg, Arther (November 12, 1984). "Jaded Memory". InfoWorld. 6 (46): p. 7. ISSN 0199-6649.

{{cite journal}}:|page=has extra text (help) Salsberg states that the Altair was named by John McVeigh - ^ H. Edward Roberts (1975). "Altair 8800 minicomputer". Popular Electronics. 7 (1). Ziff Davis: pp. 33–38.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Green, Wayne (February 1976). "Believe Me - I'm No Expert!". 73 Magazine (184). Peterborough, NH: 73, Inc: p. 89.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) Wayne Green visited MITS in August 1975 and interviewed Ed Roberts. Article has several paragraphs on the design of the Altair 8800. - ^ Intel Corporation (1984). A Revolution in Progress - A History to Date of Intel. Intel Corporation. p. 14. Order number:231295.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Freiberger, Paul (2000). Fire in the Valley: The Making of the Personal Computer. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. p. 42. ISBN 0-07-135892-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) "Roberts was sure he could get the chip price much cheaper, and he did. Intel knocked the price down to $75." - ^ Mims, Forrest (1985). "The Tenth Anniversary of the Altair 8800". Computers & Electronics. 23 (1). Ziff Davis: pp. 58–62, 81–82.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)"But because the 8080 sold for $360 in single quantities, few people could afford it. Ed Roberts bought the chips in large quantities and was able to get a substantial discount…" - ^ Ceruzzi, Paul E. (2003). A History of Modern Computing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. pp. 222–224. ISBN 0-262-53203-4.

- ^ Michalopoulos, Demetrios A. (October 1976). "New Products". Computer. 9 (10). IEEE: pp. 59–64. doi:10.1109/C-M.1976.218414.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) "Intel Corporation has announced that an interactive display console and highspeed line printer are now available for the Intellec MDS microcomputer development system. … The display console costs $2240 and the printer $3200 in quantities of 1 to 9. Delivery is in 30 days. Price of the basic Intellec MDS with 16K bytes of RAM memory, including interfaces and resident software for operating the peripherals, is $3950." - ^ Bunnell, David (August 1975). "Across the Editor's Desk". Computer Notes. 1 (3). Altair Users Group, MITS Inc.: p. 2. Retrieved 2007-12-26.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) Intel letter to its sales force. "We wish to clarify any misconception that may exist in your minds regarding the MITS ALTAIR system. This product is designed around the Intel Standard Data Sheet 8080 family." - ^ Veit, Stan (1993). Stan Veit's History of the Personal Computer. Alexander, North Carolina: WorldComm Press. p. 283. ISBN 1-56664-030-X. "Ed Roberts was able to get around this problem by obtaining a supply of cosmetic reject chips for about 1/3 the retail price."

- ^ Brillinger, P. C. (November 1970). "A complete package for introducing computer science". SIGCSE Bulletin. 2 (3). ACM: pp. 118–126. doi:10.1145/873641.873659.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Describes the introductory computer science courses at the University of Waterloo. - ^ Ceruzzi, Paul E. (2003). A History of Modern Computing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. pp. 201–206. ISBN 0-262-53203-4.

- ^ MITS (June 1975). "MITS advertisement". Digital Design. 4 (6). CMP Information. Retrieved 2008-01-01. "There was a subsequent article in February's Popular Electronics and the MITS people knew the Altair was here to stay. During that month alone, over 1,000 mainframes were sold. Datamation, March 1975." "By the end of May, MITS had shipped over 2,500 Altair 8800's"

- ^ Green, Wayne (1975). "From the Publisher .. Are they real?". BYTE. 1 (2). Green Publishing: pp. 61, 81, 87.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) In August 1975 Wayne Green visited several personal computer manufacturers. A photo caption in his trip report says; "Meanwhile, at MITS, over 5,000 Altair 8800's have been shipped. Here is a view of part of the production line." - ^ a b Roberts, H. Edward (October 1975). "Letter from the President". Computer Notes. 1 (5). Altair Users Group, MITS Inc.: p. 3. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) "We had less than 20 employees when we introduced the Altair and now we have grown to 90 as a result of our Altair customers." Roberts also discussed the problems with the 4K dynamic RAM boards. Customers got a $50 refund. - ^ MITS (1975). "Worlds Most Inexpensive BASIC language system". Popular Electronics. 8 (2). Ziff Davis: p. 1.

{{cite journal}}:|page=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Moore, Fred (July 1976). "Hardware". Homebrew Computer Club Newsletter. 1 (5): pp. 2, 5. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Littman, Jonathan (1987"). Once Upon a Time in ComputerLand: The Amazing, Billion-Dollar Tale of Bill Millard. Los Angeles: Price Stern Sloan. p. 18. ISBN 0-89586-502-5.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) "Later that day, December 16 [1975], United Parcel Service picked up the first shipment of 50 IMS computer kits for delivery to customers." - ^ Greelish, David (1996). "Ed Roberts Interview with Historically Brewed magazine". Historically Brewed (9). Historical Computer Society. Retrieved 2007-11-22. Ed Roberts said: "We had a Nova 2 by Data General in the office that we sold time share on …The front panel on an Altair essentially models every switch that was on the Nova 2. We had that machine to look at. The switches are pretty much standard of any front panel machine. It would have taken forever if we would have had to re-decide where every switch had to go. "

Further reading

- Books

- Ditlea, Steve (September 1984). Digital Deli: The Comprehensive, User-Lovable Menu of Computer Lore, Culture, Lifestyles and Fancy. Workman Publishing. ISBN 0894805916. Chapter "Solomon's Memory" by Les Solomon

- Freiberger, Paul (2000). Fire in the Valley: The Making of the Personal Computer. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-135892-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Mims, Forrest M (1986). Siliconnections: Coming of Age in the Electronic Era. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0070424111.

- Veit, Stanley (1993). Stan Veit's history of the personal computer. Asheville, N.C: WorldComm. ISBN 9781566640305.

- Young, Jeffrey S. (1998). Forbes Greatest Technology Stories: Inspiring Tales of the Entrepreneurs. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0471243744. Chapter 6 "Mechanics: Kits & Microcomputers"

- Magazines

- Greelish, David (1996). "Ed Roberts Interview with Historically Brewed magazine". Historically Brewed (9). Historical Computer Society. Retrieved 2007-11-22.

- Green, Wayne (1975). "From the Publisher .. Are they real?". BYTE. 1 (2). Green Publishing: pp. 61, 81, 87.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Mims, Forrest M. (1984). "The Altair story; early days at MITS". Creative Computing. 10 (11). Creative Computing: p. 17. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Mims, Forrest (1985). "The Tenth Anniversary of the Altair 8800". Computers & Electronics. 23 (1). Ziff Davis: pp. 58–62, 81–82.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Roberts, H. Edward (1975). "Altair 8800 minicomputer". Popular Electronics. 7 (1). New York, NY: Ziff Davis: pp. 33–38. Retrieved 2008-04-26.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- "Altair 8800". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

- MITS Altair 8800 exhibit at OLD-COMPUTERS.COM's virtual computer museum

- Virtual Altair Museum

- Help getting your Altair up and running - plus software

- Altair 8800 Emulator

- Altair 8800 images and information at www.vintage-computer.com

- Collection of old digital and analog computers at oldcomputermuseum.com

- Reproduction Altair 8800 Kits

- Marcus Bennett's Altair Documentation resource