Ali-Shir Nava'i

Ali-Shir Nava'i | |

|---|---|

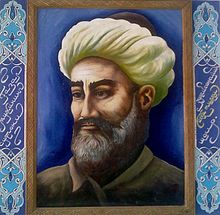

16th-century portrait of Ali-Shir Nava'i by Mahmud Muzahhib, now located in the Museum of the Astan Quds Razavi in Mashhad, Iran | |

| Born | 9 February 1441 Herat, Timurid Empire |

| Died | 3 January 1501 (aged 59) Herat, Timurid Empire |

| Resting place | Herat, Afghanistan |

| Pen name | Navā'ī (or Nevā'ī) and Fāni |

| Occupation | Poet, writer, politician, linguist, mystic and painter |

| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

|

|

|

'Ali-Shir Nava'i (9 February 1441 – 3 January 1501), also known as Nizām-al-Din ʿAli-Shir Herawī[n 1] (Chagatai: نظام الدین علی شیر نوایی, Persian: نظامالدین علیشیر نوایی) was a Timurid poet,[1] writer, statesman, linguist, Hanafi Maturidi[2] mystic and painter[3] who was the greatest representative of Chagatai literature.[4][5]

Nava'i believed that his native Chagatai Turkic[6] language was superior to Persian for literary purposes, an uncommon view at the time and defended this belief in his work titled Muhakamat al-Lughatayn (The Comparison of the Two Languages). He emphasized his belief in the richness, precision and malleability of Turkic vocabulary as opposed to Persian.

Due to his distinguished Chagatai language poetry, Nava'i is considered by many throughout the Turkic-speaking world to be the founder of early Turkic literature. Many places and institutions in Central Asia are named after him, including the province and city of Navoiy in Uzbekistan.

Many monuments and busts in honour of Alisher Navoi's memory have been erected in different countries and cities such as Tashkent, Samarkand, Navoiy of Uzbekistan, Ashgabat of Turkmenistan,[7] Ankara of Turkiye, Seoul of South Korea, Tokyo of Japan, Shanghai of China, Osh of Kyrgyzstan, Astana of Kazakhstan, Dushanbe of Tajikistan, Herat of Afghanistan, Baku of Azerbaijan, Moscow of Russia, Minsk of Belarus, Lakitelek of Hungary[8] and Washington D.C. of the USA.

Life

[edit]Alisher Nava'i was born in 1441 at the city of Herat to a family of well-read Turkic chancery scribes.[3] During Alisher's lifetime, Herat was ruled by the Timurid Empire and became one of the leading cultural and intellectual centres in the Muslim world. Alisher belonged to the Chaghatai mir class of the Timurid elite. Alisher's father, Ghiyāth al-Din Kichkina ("The Little"), served as a high-ranking officer in Khorasan in the palace of the Timurid ruler Shah Rukh. His mother served as a prince's governess in the palace. Ghiyāth al-Din Kichkina served as governor of Sabzawar at one time.[5] He died while Alisher was young, and another ruler of Khorasan, Abul-Qasim Babur Mirza, adopted guardianship of the young man.

Alisher was a schoolmate of Sultan Husayn Bayqara, who would later become sultan of Khorasan. Alisher's family was forced to flee Herat in 1447 after the death of Shah Rukh created an unstable political situation. His family returned to Khorasan after order was restored in the 1450s. In 1456, Alisher and Bayqarah went to Mashhad with Abul-Qasim Babur Mirza. The following year Abul-Qasim died and Alisher and Bayqarah parted ways. While Bayqarah tried to establish political power, Alisher pursued his studies in Mashhad, Herat, and Samarkand.[9]

After the death of Abu Sa'id Mirza in 1469, Husayn Bayqarah seized power in Herat. Consequently, Alisher left Samarkand to join his service. In 1472, Alisher was appointed emir of the dīvān-i aʿlā (supreme council), which eventually led him into a conflict with the powerful Persian bureaucrat Majd al-Din Muhammad Khvafi, due to the latter's centralising reforms, which posed a danger to the traditional privileges that the Turkic military elite (such as Alisher) enjoyed.[3] Alisher remained in the service of Bayqarah until his death on 3 January 1501. He was buried in Herat.

Alisher Nava'i led an ascetic lifestyle, "never marrying or having concubines or children."[10]

Work

[edit]Alisher served as a public administrator and adviser to his sultan, Husayn Bayqara. Mirkhvand composed his Timurid universal history under the patronage of Ali-Shir Nava’i. He was also a builder who is reported to have founded, restored, or endowed some 370 mosques, madrasas, libraries, hospitals, caravanserais, and other educational, pious, and charitable institutions in Khorasan. In Herat, he was responsible for 40 caravanserais, 17 mosques, 10 mansions, nine bathhouses, nine bridges, and 20 pools.[11]

Among Alisher's constructions were the mausoleum of the 13th-century mystical poet, Farid al-Din Attar, in Nishapur (north-eastern Iran) and the Khalasiya madrasa in Herat. He was one of the instrumental contributors to the architecture of Herat, which became, in René Grousset's words, "the Florence of what has justly been called the Timurid Renaissance".[12] Moreover, he was a promoter and patron of scholarship and arts and letters, a musician, a composer, a calligrapher, a painter and sculptor, and such a celebrated writer that Bernard Lewis, a renowned historian of the Islamic world, called him "the Chaucer of the Turks".[13]

Among the many notable figures who were financially backed by Alisher include the historians Mirkhvand (died 1498), Khvandamir (died 1535/6) and Dawlatshah Samarqandi (died 1495/1507); the poets Jami (died 1492), Asafi Harawi (died 1517), Sayfi Bukhari (died 1503), Hatefi (died 1521), and Badriddin Hilali (died 1529/30); and the musicians Shaykh Na'i and Husayn Udi.[3]

Literary works

[edit]Under the pen name Nava'i, Alisher was among the key writers who revolutionized the literary use of the Turkic languages. Nava'i himself wrote primarily in the Chagatai language and produced 30 works over a period of 30 years, during which Chagatai became accepted as a prestigious and well-respected literary language. Nava'i also wrote in Persian under the pen name Fāni, and, to a much lesser degree, in Arabic.

Nava'i's best-known poems are found in his four diwans,[4] or poetry collections, which total roughly 50,000 verses. Each part of the work corresponds to a different period of a person's life:

- Ghara'ib al-Sighar "Wonders of Childhood"

- Navadir al-Shabab "Rarities of Youth"

- Bada'i' al-Wasat "Marvels of Middle Age"

- Fawa'id al-Kibar "Benefits of Old Age"

To help other Turkic poets, Alisher wrote technical works such as Mizan al-Awzan "The Measure of Meters", and a detailed treatise on poetical meters. He also crafted the monumental Majalis al-Nafais "Assemblies of Distinguished Men", a collection of over 450 biographical sketches of mostly contemporary poets. The collection is a gold mine of information about Timurid culture for modern historians.

Alisher's other important works include the Khamsa (Quintuple), which is composed of five epic poems and is a response of Nizami Ganjavi's Khamsa:

- Hayrat al-abrar "Wonders of Good People" (حیرت الابرار)

- Farhad va Shirin "Farhad and Shirin" (فرهاد و شیرین)

- Layli va Majnun "Layla and Majnun" (لیلی و مجنون)

- Sab'ai Sayyar "Seven Travelers" (سبعه سیار) (about the seven planets)

- Sadd-i Iskandari "Alexander's Wall" (سد سکندری) (about Alexander the Great)

Alisher also wrote Lisan al-Tayr after Attar of Nishapur's Mantiq al-Tayr or "The Conference of the Birds", in which he expressed his philosophical views and ideas about Sufism. He translated Jami's Nafahat al-uns (نفحات الانس) to Chagatai and called it Nasayim al-muhabbat (نسایم المحبت). His Besh Hayrat (Five Wonders) also gives an in-depth look at his views on religion and Sufism. His book of Persian poetry contains 6,000 lines (bayts).

Nava'i's last work, Muhakamat al-Lughatayn "The Trial of the Two Languages" is a comparison of Turkic and Persian and was completed in December 1499. He believed that the Turkic language was superior to Persian for literary purposes, and defended this belief in his work.[14] Nava'i repeatedly emphasized his belief in the richness, precision and malleability of Turkic vocabulary as opposed to Persian.[15]

This is the excerpt from Nava'i's "Twenty-One Ghazals", translated into English:

Without Fortune and prospect, I ignite the fire

Of impatience – the guards of prudence have vanished:

My caravan defenseless in the coming fire.

A lightening flash has struck and changed me utterly

As rushes burst and spread in a sea of fire...

Understand, Navoiy, I deny my suffering

As the Mazandaran forests turned red with fire.[16]

List of works

[edit]- Badoyi' ul-bidoya

- Nawadir al-nihaya

Below is a list of Alisher Nava'i's works compiled by Suyima Gʻaniyeva,[17] a senior professor at the Tashkent State Institute of Oriental Studies.[18]

Badoe ul-Vasat (Marvels of Middle Age) – the third diwan of Nava'i's Hazoin ul-maoniy. It consists of 650 ghazals, one mustazod, two mukhammases, two musaddases, one tarjeband, one qasida, 60 qit'as, 10 chistons, and three tuyuks. Overall, Badoe ul-Vasat has 740 poems and is 5,420 verses long. It was compiled between 1492 and 1498.

Waqfiya – a documentary work by Nava'i. He wrote it under the pen name Fāni in 1481. Waqfiya depicts the poet's life, spiritual world, dreams, and unfulfilled desires. Waqfiya is an important source of information about the social and cultural life in the 15th century.

Layli wa Majnun (Layli and Majnun) – the third dastan in the Khamsa. It is about a man mad with love. Layli wa Majnun is divided into 36 chapters and is 3,622 verses long. It was written in 1484.

Lison ut-Tayr – an epic poem that is an allegory for the man's need to seek God. The story begins with the birds of the world realizing that they are far from their king and need to seek him. They begin the long and hard journey with many complaints, but a wise bird encourages them through admonishment and exemplary stories. Nava'i wrote Lison ut-Tayr under the pen name Fāni between 1498 and 1499. The poem is 3,598 verses long. In the introduction, the author notes that he wrote this poem as a response to Attar of Nishapur's Mantiq-ut Tayr.

Majolis un-Nafois – Nava'i's tazkira (anthology). Written in 1491–92, the anthology was completed with additions in 1498. It consists of eight meeting reports and has much information about some poets of Nava'i's time. Overall, in Majolis un-Nafois Nava'i wrote about 459 poets and authors. The work was translated three times into Persian in the 16th century. It has also been translated into Russian.

Mahbub ul-Qulub – Nava'i's work written in 1500, a year before his death. Mahbub ul-Qulub consists of an introduction and three main sections. The first part is about status and the duties of different social classes; the second part is about moral matters; the third, final part contains advice and wise sayings. Mahbub ul-Qulub has been translated into Russian. Some of the stories contained within this work originate from the Sanskrit book Kathāsaritsāgara which has, for example, the “Story of King Prasenajit and the Brāhman who lost his Treasure”.[19]

Mezon ul-Avzon – Nava'i's work about Persian and Turkic aruz. Mezon ul-Avzon was written in 1490.

Minhoj un-Najot (The Ways of Salvation) – the fifth poem in the Persian collection of poems Sittai zaruriya (The Six Necessities). Minhoj un-Najot is 138 verses long. It was written in response to Khaqani's and Ansori's triumphal poems.

Munojot – a work written in prose by Nava'i in the last years of his life. It is a small work about pleading and repenting before Allah. In Munojot, Nava'i wrote about his unfulfilled dreams and regrets. The work was translated into English in 1990. It has also been translated into Russian.

Munshaot (A Collection of Letters) – a collection of Nava'i's letters written to different classes of people about various kinds of matters. The collection also includes letters addressed to Nava'i himself and his adopted son. Munshaot was collected between 1498 and 1499. The work contains information about Husayn Bayqarah and Badi' al-Zaman Mirza. It also contains letters expressing Nava'i's dream about performing the Hajj pilgrimage. In Munshaot, Nava'i provides much insight about political, social, moral, and spiritual matters.

Mufradot – Nava'i's work about problem solving written in 1485. In this work, Nava'i discussed the many different types of problems and offered his own solutions. The first section of Mufradot entitled Hazoin-ul-maoni contains 52 problems in Chagatai and the second section entitled Devoni Foni contains 500 problems in Persian.

Muhakamat al-Lughatayn – Nava'i's work about his belief in the richness, precision and malleability of Turkic as opposed to Persian. In this work, Nava'i also wrote about some poets who wrote in both of these languages. Muhakamat al-Lughatayn was written in 1499.

Navodir ush-Shabob (Rarities of Youth) – the second diwan of Nava'i's Hazoin ul-maoniy. Navodir ush-Shabob contains 650 ghazals, one mustazod, three muhammases, one musaddas, one tarjeband, one tarkibband, 50 qit'as, and 52 problems. Overall, the diwan has 759 poems and is 5,423.5 verses long. Navodir ush-Shabob was compiled between 1492 and 1498.

Nazm ul-Javohir – Nava'i's work written in 1485 in appreciation of Husayn Bayqarah's risala. In Nazm ul-Javohir, the meaning of every proverb in Ali's collection of proverbs entitled Nasr ul-laoliy is told in one ruba'i. The creation and purpose of the work is given in the preface.

Nasim ul-Huld – Nava'i's qasida written in Persian. The qasida was influenced by Khaqani's and Khusrow Dehlawī's works. The Russian historian Yevgeniy Bertels believed that Nasim ul-Huld was written in response to Jami's Jilo ur-ruh.

Risolai tiyr andohtan – a short risala that has only three pages. The risala, which seems to be a commentary on one of the hadiths, was included in Nava'i's unfinished work Kulliyot. Kulliyot was published as a book in 1667–1670 and consisted of 17 works. In his book Navaiy, Yevgeniy Bertels chose Risolai tiyr andohtan as the last work in his list of 22 works by Nava'i.

Rukh ul-Quds (The Holy Spirit) – the first qasida in Nava'i's Persian collection of qasidas entitled Sittai zaruriya. Rukh ul-Quds, which is 132 verses long, is about divine love.

Sab'ai Sayyor (Seven Travelers) – the fourth dastan in Nava'i's Khamsa. Sab'ai Sayyor is divided into 37 chapters and is 8,005 lines long. The poem was written in 1485.

Saddi Iskandari (Alexander's Wall) – the fifth dastan in Nava'i's Khamsa. In this work, Nava'i positively portrays the conquests of Alexander the Great and expresses his views on governance. Saddi Iskandari was written in 1485 and consists of 88 chapters and is 7,215 verses long.

Siroj ul-Muslimin (The Light of Muslims) – Nava'i's work about Islamic Law. Siroj ul-Muslimin was written in 1499 and discusses the five pillars of Islam, sharia, namaz, fasting, the Hajj pilgrimage, signs of God, religious purity, and zakat. The work was first published in Uzbekistan in 1992.

Tarixi muluki Ajam – Nava'i's work about the Shahs of Iran. The work describes the good deeds that the Shahs performed for their people. Tarixi muluki Ajam was written in 1488.

Tuhfat ul-Afkor – Nava'i's qasida in Persian written as a response to Khusrow Dehlawī's Daryoi abror. This work was also influenced by Jami's qasida Lujjat ul-asror. Tuhfat ul-Afkor is one of the six qasidas included in Nava'i's collection of poems Sittai zaruriya.

Favoid ul-Kibar (Benefits of Old Age) – the fourth diwan in Nava'i's Hazoin ul-maoniy. The work consists of 650 ghazals, one mustazod, two muhammases, one musaddas, one musamman, one tarjeband, one sokiynoma, 50 qit'as, 80 fards, and 793 poems. Favoid ul-Kibar is 888.5 verses long. It was written between 1492 and 1498.

Farhod wa Shirin (Farhad and Shirin) – the second dastan in Nava'i's Khamsa. Farhod wa Shirin, which was written in 1484, is often described as a classic Romeo and Juliet story for Central Asians. The poem is divided into 59 chapters and is 5,782 verses long.

Fusuli arba'a (The Four Seasons) – the common title of the four qasidas written in Persian by Nava'i. Each qasida is about one of the four seasons – Spring (57 verses), The Hottest Part of Summer (71 verses), Autumn (35 verses), and Winter (70 verses).

Hazoin ul-Maoniy – the common title of the four diwans that include Nava'i's completed lyric poems. Hazoin ul-maoniy consists of 2,600 ghazals, four mustazods, ten muhammases, four tarjebands, one tarkibband, one masnaviy (a poetic letter to Sayyid Khsan), one qasida, one sokiynoma, 210 qit'as, 133 ruba'is, 52 problems, 10 chistons, 12 tuyuks, 26 fards, and 3,132 poems. Hazoin ul-Maoniy is 22,450.5 verses (44,901 lines) long. It was finished in 1498. Sixteen different lyrical genres are used in this collection.

Khamsa – the common title of the five dastans by Nava'i that were written in 1483–85. With this work Nava'i established a precedent for quality literature in Chagatay. The five dastans included in Nava'i's Khamsa are:

- Hayrat ul-Abror (Wonders of Good People) – 64 chapters, 3,988 verses long; written in 1483;

- Farhad wa Shirin (Farhad and Shirin) – 59 chapters, 5,782 verses long; written in 1484;

- Layli wa Majnun (Layli and Majnun) – 36 chapters, 3,622 verses long; written in 1484;

- Sab'ai Sayyor (Seven Travelers) – 37 chapters, 8,008 verses long; written in 1485;

- Saddi Iskandari (Alexander's Wall) – 83 chapters, 7,215 verse long; written in 1485.

Hamsat ul-Mutaxayyirin – Nava'i's work about Jami written in 1494. The work consists of an introduction, three sections, and a conclusion. In the introduction, Nava'i writes about Jami's genealogy, birth, upbringing, studies, and about how he became a scientist and a poet. The first part tells about Jami's spiritual world, and his ideas about creative works; the second part reveals the closeness between Nava'i and Jami in creative collaborations. The conclusion sheds light on Jami's death. It includes Nava'i's eulogy in Persian that consists of seven sections of ten lines.

Gharoyib us-Sighar (Wonders of Childhood) – the first diwan in Nava'i's Hazoin ul-maoniy. The work consists of 650 ghazals, one mustazod, three muhammases, one musaddas, one tarjeband, one masnaviy, 50 qit'as, 133 ruba'is, and 840 poems. Gharoyib us-Sighar is 5,718.5 verses (11,437 lines) long. It was compiled between 1492 and 1498.

Hayrat ul-Abror (Wonders of Good People) – the first dastan in Nava'i's Khamsa. The work is divided into 64 chapters and is 3,988 verses long. Hayrat ul-Abror was written in 1483.

Influence of Nava'i

[edit]In his poem, Nava'i wrote that his poems were popular amongst the Turkic peoples not only in Khorasan, but also amongst the enthusiasts of the poetry of Shiraz and Tabriz:[20]

- No Matter how many there are one – a hundred, a thousand,

- All the Turkic languages belong to me.

- Without warriors nor battles I conquered every country,

- From China to Khorasan.

- Sugar from the cane of my quill.

- Was strewn not only on Khorasan, but also on Shiraz and Tabriz

Moreover, Nava'i stresses that his poems received recognition not only amongst the Turkic peoples, but also amongst the Oghuz Turks:[20]

- The Turks devote their heart and soul to my words.

- And not just the Turks, but also the Turkmen as well.

These words prove the bayt below of the poet Nematullah Kishvari, who lived and worked in the Aq Qoyunlu during the rule of Sulatn Yaqub, and who was envious of the Timurid court:[20]

- Kishwarī's poems are not inferior to Nawā'ī's.

- If only lucky fate would send him a protector such as Sulṭan Ḥusayn Bayqara.

This means that the Aq Qoyunlu saw the environment of the Ḥusayn Bāyqarā court as a model environment.

Nava'i had a great influence in areas as distant as India to the east and the Ottoman Empire to the west. His influence can be found in Central Asia, modern day Turkey, Kazan of Russia, and all other areas where Turkic speakers inhabit.

- Babur, founder of the Mughal Empire in India and the author of Baburnama, was heavily influenced by Nava'i and wrote about his respect for the writer in his memoirs.

- The Ottomans were highly conscious of their Central Asian heritage; Süleymân the Magnificent was impressed by Nava'i and had Divan-i Neva'i, Khamsa, and Muhakamat added to his personal library.[21]

- The renowned Azerbaijani poet Fuzûlî, who wrote under the auspices of both the Safavid and Ottoman empires, was heavily influenced by the style of Nava'i.

- The role of Nava'i in the Turkmen literature and art has been considered significant since several classic Turkmen poets regarded him as their ustad (master). Turkmen poet Magtymguly refers to Nava'i on numerous occasions in his poetry calling him a brilliant poet and his master.[22]

- Bukhara Emir Muzaffar presented the manuscript of Navoi's Divan to British Queen Victoria in 1872.[23]

- Nava'i is considered the national poet of Uzbekistan in Uzbek culture. The province of Navoi is named in his honor, as well as many other landmarks such as streets and boulevards. It is an ongoing trend for Uzbek authors and poets to take inspiration from his works.[24]

Legacy

[edit]Nava'i is one of the most beloved poets among Central Asian Turkic peoples. He is generally regarded as the greatest representative of Chagatai language literature.[4][5] His mastery of the Chagatai language was such that it became known as "the language of Nava'i".[4]

Although all applications of modern Central Asian ethnonyms to people of Nava'i's time are anachronistic, Soviet and Uzbek sources regard Nava'i as an ethnic Uzbek.[25][26][27] According to Muhammad Ḥaidar, who wrote the Tarikh-i-Rashidi, Ali-sher Nava'i was a descendant of Uighur Bakhshi scribes,[28] which has led some sources to call Nava'i a descendant of Uyghurs.[5][29][30] However, other scholars such as Kazuyuki Kubo disagree with this view.[31][32]

Soviet and Uzbek sources hold that Nava'i significantly contributed to the development of the Uzbek language and consider him to be the founder of Uzbek literature.[25][26][33][34] In the early 20th century, Soviet linguistic policy renamed the Chagatai language "Old Uzbek", which, according to Edward A. Allworth, "badly distorted the literary history of the region" and was used to give authors such as Alisher Nava'i an Uzbek identity.[24] According to Charles Kurzman, "Ironically, given Navoi's distaste for the Uzbeks of his day, his legacy is being corralled for [a] strain of nationalism-building: the revaluation of the Uzbek language."[35]

In December 1941, the entire Soviet Union celebrated Nava'i's five-hundredth anniversary.[36] In Nazi-blockaded Leningrad, Armenian orientalist Joseph Orbeli led a festival dedicated to Nava'i. Nikolai Lebedev, a young specialist in Eastern literature who suffered from acute dystrophy and could no longer walk, devoted his life's last moments to reading Nava'i's poem Seven Travelers.[37]

Many places and institutions in Uzbekistan and other Central Asian countries are named after Alisher Nava'i. Navoiy Region, the city of Navoiy, the National Library of Uzbekistan named after Alisher Navoiy,[38] the Alisher Navoi Opera and Ballet Theatre, Alisher Navoiy station of Tashkent Metro, and Navoiy International Airport – all are named after him.

Many of Nava'i's ghazals are performed in the Twelve Muqam, particularly in the introduction known as Muqäddimä.[39] They also appear in popular Uzbek folk songs and in the works of many Uzbek singers, such as Sherali Jo‘rayev. Alisher Nava'i's works have also been staged as plays by Uzbek playwrights.[10]

In 2021, an international spiritual event dedicated to the 580th anniversary of Ali-Shir Nava'i was held at the House of Friendship in Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan.[40]

Notes

[edit]- ^ In the early new Persian and the eastern contemporary variants of the Persian language, there are two different vowels ī and ē which are shown by the same Perso-Arabic letter ی and in the standard transliteration, both of them are usually transliterated as ī. However, when the distinction of ī and ē is considered, his first name should be transliterated as Alisher

References

[edit]- ^ Robinson, Chase; Foot, Sarah, eds. (2012). The Oxford History of Historical Writing Volume 2: 400-1400. Oxford University Press. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-191-63693-6.

... biographies on individuals only started to appear in larger numbers during the late fifteenth century under the Timurid dynasty, such as Khvandamir's glorification of his patron, the Timurid poet and statesman Mir Ali Shir Navai

- ^ Nava'i, Ali-Shir (1996). Nasa'em al-mahabba men shama'em al-fotowwa. Turkish Language Association. p. 392.

- ^ a b c d Subtelny 2011.

- ^ a b c d Robert McHenry, ed. (1993). "Navā'ī, (Mir) 'Alī Shīr". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (15th ed.). Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. p. 563.

- ^ a b c d Subtelny 1993, p. 90-93.

- ^ Dabashi, Hamid (2012). The World of Persian Literary Humanism. Harvard University Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-674-06759-2.

... in his (Nava'i's) own poetic and literary capabilities and wrote both in his native Chagatai Turkish and also in Persian, ...

- ^ "Literary voyage through the Magtymguly Fragi cultural and park complex". 29 May 2024.

- ^ Shohruh H. (15 October 2024). "A bust of Alisher Navoi was installed in Lakitelek, Hungary". gazeta.uz (in Uzbek). Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ Subtelny 1993, p. 90.

- ^ a b Subtelny 1993, p. 92.

- ^ "Alisher Navoi". Complete Works in 20 Volumes. Vol. 1–18. Tashkent. 1987–2002.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Subtelny, Maria Eva (November 1988). "Socioeconomic Bases of Cultural Patronage under the Later Timurids". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 20 (4): 479–505. doi:10.1017/s0020743800053861. S2CID 162411014.

- ^ Hoberman, Barry (January–February 1985). "Chaucer of the Turks". Saudi Aramco World: 24–27.

- ^ Subtelny 1993, p. 91.

- ^ Ali Shir Nava'i Muhakamat al-lughatain tr. & ed. Robert Devereaux (Leiden: Brill) 1966

- ^ "Twenty-One Ghazals [of] Alisher Navoiy"

translated from Uzbek by Dennis Daly, Cervena Barva Press, Somerville, MA, (2016) - ^ "Suyima Gʻaniyeva". ZiyoNet (in Uzbek). Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ Suima Ganieva. "The Alisher Navoi Reference Bibliography". Navoi's Garden. Archived from the original on 5 August 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ^ Tawney, C. H. (1924). The Ocean of Story, volume 1. p. 118-n1.

- ^ a b c Aftandil Erkinov (2015). "From Herat to Shiraz: the Unique Manuscript (876/1471) of 'Alī Shīr Nawā'ī's Poetry from Aq Qoyunlu Circle". Cahiers d'Asie centrale: 47–49.

- ^ Rogers, J. M.; R. M. Ward (1988). Suleyman the Magnificent. Vol. 7. British Museum Publications. pp. 93–99. ISBN 0-7141-1440-5.

- ^ Nūrmuhammed, Ashūrpūr (1997). Explanatory Dictionary of Magtymguly. Iran: Gonbad-e Qabous. pp. 21–101. ISBN 964-7836-29-5.

- ^ JOHN SEYLLER, A MUGHAL MANUSCRIPT OF THE «DIWAN» OF NAWA’I in Artibus Asiae, Vol. 71, No. 2 (2011), pp. 325—334

- ^ a b Allworth, Edward A. (1990). The Modern Uzbeks: From the Fourteenth Century to the Present: A Cultural History. Hoover Institution Press. pp. 229–230. ISBN 978-0-8179-8732-9.

- ^ a b Valitova 1974, p. 194–195.

- ^ a b A. M. Prokhorov, ed. (1997). "Navoi, Nizamiddin Mir Alisher". Great Encyclopedic Dictionary (in Russian) (2nd ed.). Saint Petersburg: Great Russian Encyclopedia. p. 777.

- ^ Umidbek (9 February 2011). "Alisher Nava'i Remembered in Moscow". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (in Uzbek). Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ^ Subtelny, Maria Eva (1979–1980). 'Alī Shīr Navā'ī: Bakhshī and Beg. Eucharisterion: Essays presented to Omeljan Pritsak on his Sixtieth Birthday by his Colleagues and Students. Vol. 3/4. Harvard Ukrainian Studies. p. 799.

- ^ Paksoy, H. B. (1994). Central Asia Reader: The Rediscovery of History. M.E. Sharpe. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-56324-202-1.

- ^ Kutlu, Mustafa (1977). Türk Dili ve Edebiyatı Ansiklopedisi: Devirler, İsimler, Eserler, Terimler. Vol. 7. Dergâh Yayınları. p. 37.

- ^ Golombek, Lisa (1992). Timurid Art and Culture: Iran and Central Asia in the Fifteenth Century. Brill. p. 47.

- ^ Kabo, Kazuyuki (1990). "ミール・アリー・シールの学芸保護について" [Mir 'Ali Shir's Patronage of Science and Art]. 西南アジア研究: 22–24.

- ^ "Alisher Navoi". Writers Festival. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ^ Maxim Isaev (7 July 2009). "Uzbekistan – The monuments of classical writers of oriental literature are removed in Samarqand". Ferghana News. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ^ Kurzman, C. (1999). Uzbekistan: The invention of nationalism in an invented nation. Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies, 8(15), p. 86

- ^ Grigol Ubiria (2015). Soviet Nation-Building in Central Asia: The Making of the Kazakh and Uzbek Nations. Routledge. p. 232. ISBN 9781317504351.

- ^ Harrison Salisbury (2003). The 900 Days: The Siege Of Leningrad. Da Capo Press. p. 430. ISBN 9780786730247.

- ^ "About the National Library of Uzbekistan named after Alisher Navoiy". the National Library of Uzbekistan named after Alisher Navoiy. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ^ Nathan Light. Intimate Heritage: Creating Uyghur Muqam Song in Xinjiang. Berlin. Lit Verlag, 2008.

- ^ February 2021, Zhanna Shayakhmetova in Central Asia on 23 (23 February 2021). "Kazakh Capital Hosts a Poetry Event to Commemorate 580th Anniversary of Poet Alisher Navoi". The Astana Times. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Sources

[edit]- Subtelny, Maria Eva (1993). "Mīr 'Alī Shīr Nawā'ī". In C. E. Bosworth; E. Van Donzel; W. P. Heinrichs; Ch. Pellat (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Islam. Vol. VII. Leiden—New York: E. J. Brill.

- Subtelny, Maria Eva (2011). "ʿAlī Shīr Navāʾī". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Valitova, A. A. (1974). "Alisher Navoi". In A. M. Prokhorov (ed.). Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Vol. XVII. Moscow: Soviet Encyclopedia.

- Khwandamir (1979), Gandjei, T. (ed.), Makarim al-akhlak, Leiden

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Babur (1905), Beveridge, A. S. (ed.), The Baburnama, Tashkent

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Semenov, A. A. (1940), Materiali k bibliograficheskomy ukazatelyu pechatnykh proizvedeniy Alishera Navoi i literatury o nem. (Materials for a Bibliography of the Published Works of Alī Shīr Navā'ī and the Secondary Literature on Him), Tashkent

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Levend, Agâh Sırri (1965–1968), Ali Şîr Nevaî, Ankara

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Aybek, M. T., ed. (1948), Velikiy uzbekskiy poet. Sbornik statey (The Great Uzbek Poet), Tashkent

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Erkinov, A. (1998), "The Perception of Works by Classical Authors in the 18th and 19th centuries Central Asia: The Example of the Xamsa of Ali Shir Nawa`i", in Kemper, Michael; Frank, Allen (eds.), Muslim Culture in Russia and Central Asia from the 18th to the Early 20th Centuries, vol. 2, Berlin, pp. 513–526

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Nemati Limai, Amir (2015), Analysis of the Political Life of Amir Alishir Navai and Exploring His Cultural, Scientific, Social and Economic Works, Tehran & Mashhad: MFA (Cire)& Ferdowsi University.

External links

[edit]- 1441 births

- 1501 deaths

- People from Herat

- 15th-century writers

- Sufis

- Hanafis

- Maturidis

- Chagatai-language writers

- 15th-century Persian-language poets

- 15th-century Arabic-language poets

- Scholars from the Timurid Empire

- Officials of the Timurid Empire

- Poets from the Timurid Empire

- Iranian Arabic-language poets

- Poets of the medieval Islamic world

- Panchatantra