Alexandre Pétion

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2017) |

Alexandre Pétion | |

|---|---|

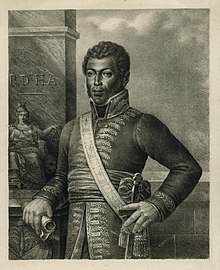

Lithograph portrait of Alexandre Pétion | |

| 1st President of Haiti | |

| In office 9 March 1807[1] – 29 March 1818 | |

| Preceded by | Henri Christophe (as first President of Hayti) |

| Succeeded by | Jean-Pierre Boyer |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Anne Alexandre Sabès 2 April 1770 Port-au-Prince, Saint-Domingue |

| Died | 29 March 1818 (aged 47) Port-au-Prince, Haiti |

| Nationality | Haitian |

| Spouse | Marie-Madeleine Lachenais |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | French Revolutionary Army Armée Indigène[2] |

| Years of service | 1791–1803 |

| Rank | General |

| Battles / wars | Haitian Revolution |

Alexandre Sabès Pétion (French pronunciation: [alɛksɑ̃dʁ sabɛs petjɔ̃]; 2 April 1770 – 29 March 1818) was the first president of the Republic of Haiti from 1807 until his death in 1818. One of Haiti's founding fathers, Pétion belonged to the revolutionary quartet that also includes Toussaint Louverture, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and his later rival Henri Christophe. Regarded as an excellent artilleryman in his early adulthood,[3] Pétion would distinguish himself as an esteemed military commander with experience leading both French and Haitian troops. The 1802 coalition formed by him and Dessalines against French forces led by Charles Leclerc would prove to be a watershed moment in the decade-long conflict, eventually culminating in the decisive Haitian victory at the Battle of Vertières in 1803.[3]

Early life

[edit]Pétion was born "Anne Alexandre Sabès" in Port-au-Prince to Pascal Sabès, a wealthy French father and Ursula, a free mulatto woman,[4] which made him a quadroon (a quarter African ancestry).[5][6] Like other gens de couleur libres (free people of color) with wealthy fathers, Pétion was sent to France in 1788 to be educated and study at the Military Academy in Paris.[7]

In Saint-Domingue, as in other French colonies such as Louisiane, the free people of color constituted a third caste between the whites and enslaved Africans. While restricted in political rights, many received social capital from their fathers and became educated and wealthy landowners, resented by the petits blancs, who were mostly minor tradesmen. Following the French Revolution, the gens de couleur led a rebellion to gain the voting and political rights which they believed were due them as French citizens; this was before the 1791 slave rebellion. At that time, most free people of color did not support freedom or political rights for slaves.[citation needed]

Haitian Revolution

[edit]Pétion returned to Saint-Domingue as a young man to take part in the Haitian Revolution, participating in skirmishes with British forces in northern Saint-Domingue. There had long been racial and class tensions between the gens de couleur and enslaved and free blacks in Saint-Domingue, where the enslaved black population outnumbered the white and gens de couleur by ten to one. During the years of warfare against French planters (commonly referred to as grands blancs), racial tensions in Saint-Domingue were exacerbated in competition for power and political alliances.[7]

When tensions arose between full blacks and mulattoes, Pétion frequently supported the mulatto faction. He allied with General André Rigaud and Jean-Pierre Boyer against Toussaint Louverture in a failed rebellion, the so-called "War of Knives", in the South of Saint-Domingue, which began in June 1799. By November, the rebels were pushed back to the strategic southern port of Jacmel; the defence was commanded by Pétion. The town fell in March 1800 and the rebellion was effectively over. Pétion and other mulatto leaders went into exile in France.[7]

In February 1802, General Charles Leclerc arrived with tens of warships and 32,000 French troops to bring Saint-Domingue under more control. Gens de couleur Petion, Boyer, and Rigaud returned with him in the hope of securing power in the colony.[7]

Following the French deportation of Toussaint Louverture and the renewed struggle, Pétion joined the nationalist force in October 1802. This followed a secret conference at Arcahaie, where Pétion supported Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the general who had captured Jacmel. The rebels took the capital of Port-au-Prince on October 17, 1803. Dessalines proclaimed independence on 1 January 1804, naming the nation Haiti. On 6 October 1804, Dessalines declared himself ruler for life and was crowned Emperor of Haiti as Jacques I.[7]

Post-revolution

[edit]

Disaffected members of Emperor Dessalines's administration, including Pétion and Henri Christophe, began a conspiracy to overthrow Dessalines. Following the assassination of Dessalines on 17 October 1806, Pétion championed the ideals of democracy and clashed with Henri Christophe who wanted absolute rule. Christophe was elected president, but he did not believe the position had sufficient power, as Pétion kept powers for himself. Christophe went to the north with his followers and established an autocracy, declaring the State of Haiti. The loyalties of the country divided between them, and the tensions between the blacks and mulattoes of the North and South, respectively, were reignited.

Pétion was elected President in 1807 of the southern Republic of Haiti. After the inconclusive struggle dragged on until 1810, a peace treaty was agreed to, and the country was split in two. In 1811, Christophe made himself king of the northern Kingdom of Haiti.

On 2 June 1816, Pétion modified the terms of the presidency in the constitution, making himself president for life.[8] Initially a supporter of democracy, Pétion found the constraints imposed on him by the senate onerous and suspended the legislature in 1818.[9]

Pétion seized commercial plantations from the rich gentry. He had the land redistributed to his supporters and the peasantry, earning him the nickname Papa Bon-Cœur ("good-hearted father"). The land seizures and changes in agriculture reduced the production of commodities for the export economy. Most of the population became full subsistence farmers, and exports and state revenue declined sharply, making survival difficult for the new state.[10]

Believing in the importance of education, Pétion started the Lycée Pétion in Port-au-Prince. Petion's virtues and ideals of freedom and democracy for the world (and especially slaves) were strong, and he often showed support for the oppressed. He gave sanctuary to the independence leader Simón Bolívar in 1815 and provided him with material and infantry support. This vital aid played a defining role in Bolivar's success in liberating the countries of what would make up Gran Colombia.[11] Petion was reported to be influenced by his (and his successor's) lover, Marie-Madeleine Lachenais, who acted as his political adviser.[12]

Pétion named General Boyer as his successor as president of the Republic of Haiti; he took control in 1818 following the death of Pétion from yellow fever. After Henri Christophe of the Kingdom of Haiti and his son died in 1820, Boyer reunited the nation under his rule.

References

[edit]- ^ Mellen, Joan (November 2012). Our Man in Haiti: George de Mohrenschildt and the CIA in the Nightmare Republic. Trine Day. p. 7. ISBN 9781936296538. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ^ Fombrun, Odette Roy, ed. (2009). "History of The Haitian Flag of Independence" (PDF). The Flag Heritage Foundation Monograph And Translation Series Publication No. 3. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ^ a b Perry, James (2005). Arrogant Armies: Great Military Disasters and the Generals Behind Them. Edison: CastleBooks. pp. 72, 85.

- ^ Ripley, George; Dana, Charles A., eds. (1872). "The New American Encyclopaedia: A Popular Dictionary of General Knowledge XIII". p. 198. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ^ Barnard, Frederick A. P.; Arnold Guyot, eds. (1886). Johnson's (revised) Universal Cyclopaedia: A Scientific and Popular Treasury of Useful Knowledge. Vol. 6. A.J. Johnson & Co. p. 221. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ^ Battier, Alcibiade Fleury; Rafina, Gesner (1881). "Sous les Bambous: Poésies" (in French). p. 209. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Fenton, Louise, Pétion, Alexander Sabès (1770-1818) in Rodriguez, Junius P., ed. Encyclopedia of slave resistance and rebellion. Vol. 2. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007. p374-375

- ^ "Constitution of Haiti from 27 December 1806, and its revision from 2 June 1816, year 13 of independence". Saint Marc. 1820. p. Article 142.

- ^ Senauth, Frank (2011). The Making and the Destruction of Haiti. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse. p. 25. ISBN 9781456753832.

- ^ Jenson, Deborah (2012). Beyond the slave narrative: politics, sex, and manuscripts in the Haitian revolution. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. p. 185. ISBN 9781846317606.

- ^ Marion, Alexandre Pétion; Ignace Despontreaux Marion; Simón Bolívar (1849). Expédition de Bolivar (in French). Port-au-Prince: De l'imp. de Jh. Courtois.

- ^ "Femmes d'Haïti - Marie-Madeleine (Joute) Lachenais". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

External links

[edit]- Works by Pétion at the Internet Archive

- 1770 births

- 1818 deaths

- 19th-century Haitian politicians

- Deaths from yellow fever

- Free people of color

- Haitian generals

- Haitian independence activists

- Haitian people of French descent

- Haitian revolutionaries

- Infectious disease deaths in Haiti

- Mulatto Haitians

- People from Port-au-Prince

- People from Saint-Domingue

- People of the Haitian Revolution

- Presidents for life

- Presidents of Haiti