Christian views on alcohol

Christian views on alcohol are varied. Throughout the first 1,800 years of Church history, Christians generally consumed alcoholic beverages as a common part of everyday life and used "the fruit of the vine"[1] in their central rite—the Eucharist or Lord's Supper.[2][3] They held that both the Bible and Christian tradition taught that alcohol is a gift from God that makes life more joyous, but that over-indulgence leading to drunkenness is sinful.[4][5][6][7] However, the alcoholic content of ancient alcoholic beverages was significantly lower than that of modern alcoholic beverages.[8][9][10] The low alcoholic content was due to the limitations of fermentation and the nonexistence of distillation methods in the ancient world.[11][8] Rabbinic teachers wrote acceptance criteria on consumability of ancient alcoholic beverages after significant dilution with water, and prohibited undiluted wine.[9]

In the mid-19th century, some Protestant Christians moved from a position of allowing moderate use of alcohol (sometimes called "'moderationism") to either deciding that not imbibing was wisest in the present circumstances ("abstentionism") or prohibiting all ordinary consumption of alcohol because it was believed to be a sin ("prohibitionism").[12] Many Protestant churches, particularly Methodists, advocated abstentionism or prohibitionism and were early leaders in the temperance movement of the 19th and 20th centuries.[13] Today, all three positions exist in Christianity, but the original position of alcohol consumption being permissible remains the most common and dominant view among Christians worldwide, in addition to the adherence by the largest bodies of Christian denominations, such as Anglicanism, Lutheranism, Roman Catholicism, and Eastern Orthodoxy.[14]

Alcohol in the Bible

[edit]Alcoholic beverages appear in the Bible, both in usage and in poetic expression. The Bible is ambivalent towards alcohol, considering it both a blessing from God that brings merriment and a potential danger that can be unwisely and sinfully abused.[15][16][17] Christian views on alcohol come from what the Bible says about it, along with Jewish and Christian traditions. The biblical languages have several words for alcoholic beverages,[7][18] and though prohibitionists and some abstentionists dissent,[19][20][21][22] there is a broad consensus that the words did ordinarily refer to intoxicating drinks.[7][15][17][23][24][25][26][excessive citations]

The commonness and centrality of wine in daily life in biblical times is apparent from its many positive and negative metaphorical uses throughout the Bible.[27][28] Positively, for example, wine is used as a symbol of abundance, and of physical blessing.[29] Negatively, wine is personified as a mocker and beer a brawler,[30] and drinking a cup of strong wine to the dregs and getting drunk are sometimes presented as a symbol of God's judgment and wrath.[31]

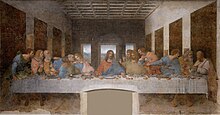

The Bible also speaks of wine in general terms as a bringer and concomitant of joy, particularly in the context of nourishment and feasting.[32] Wine was commonly drunk at meals,[33] and the Old Testament prescribed it for use in sacrificial rituals and festal celebrations.[7] The Gospel of John recorded the first miracle of Jesus: making copious amounts[34] of wine at the wedding feast at Cana.[35] Jesus instituted the ritual of the Eucharist at the Last Supper during a Passover celebration,[36] he says that the "fruit of the vine"[37][38] is a "New Covenant in [his] blood,"[39] though Christians have differed on the implications of this statement (see Eucharistic theologies contrasted).[40] Alcohol was also used for medicinal purposes in biblical times, and it appears in that context in several passages—as an oral anesthetic,[41] a topical cleanser and soother,[42] and a digestive aid.[43]

Kings and priests in the Old Testament were forbidden to partake of wine at various times.[44] John the Baptist was a Nazirite from birth.[45] Nazirite vows excluded not only wine, but also vinegar, grapes, and raisins.[46] (Jesus evidently did not take such a vow during the three years of ministry depicted in the gospels, but in fact was even accused by the Pharisees of eating and drinking with sinners).[47][48] St. Paul further instructs Christians regarding their duty toward immature Christians: "It is better not to eat meat or drink wine or to do anything else that will cause your brother to fall."[49] Jewish priests cannot bless a congregation after consuming alcohol.[50]

Virtually all Christian traditions hold that the Bible condemns ordinary drunkenness in many passages,[51] and Easton's Bible Dictionary says, "The sin of drunkenness ... must have been not uncommon in the olden times, for it is mentioned either metaphorically or literally more than seventy times in the Bible."[7] Additionally, the consequences of the drunkenness of Noah[52] and Lot[53] "were intended to serve as examples of the dangers and repulsiveness of intemperance."[54] St. Paul later chides the Corinthians for becoming drunk on wine served at their attempted celebrations of the Eucharist.[55]

Winemaking in biblical times

[edit]Both the climate and land of Palestine, where most of the Bible takes place, were well-suited to growing grapes,[56] and the wine that the vineyards produced was a valued commodity in ancient times, both for local consumption and for its value in trade.[57][58] Trade with Egypt was quite extensive. Jews were a wine-drinking culture well before the foundation of Rome. Vintage wines were found in the tomb of King Scorpion in Hierakonpolis. Archaeological evidence suggests that Semitic predecessors were thought to be responsible for the vintages that were found in the tomb.[59] Vineyards were protected from robbers and animals by walls, hedges, and manned watchtowers.[60]

In Hebrew, grape juice need not ferment before it is called wine: "When the grapes have been crushed and the wine [yayin] begins to flow, even though it has not descended into the cistern and is still in the wine press...".[61]

The harvest time brought much joy and play,[62] as "[m]en, women and children took to the vineyard, often accompanied by the sound of music and song, from late August to September to bring in the grapes."[63][64] Some grapes were eaten immediately, while others were turned into raisins. Most of them, however, were put into the wine press where the men and boys trampled them, often to music.[63] The Feast of Booths was a prescribed holiday that immediately followed the harvest and pressing of the grapes.[65]

The fermentation process started within six to twelve hours after pressing, and the must was usually left in the collection vat for a few days to allow the initial, "tumultuous" stage of fermentation to pass. The wine makers soon transferred it either into large earthenware jars, which were then sealed, or, if the wine were to be transported elsewhere, into wineskins (that is, partially tanned goat-skins, sewn up where the legs and tail had protruded but leaving the opening at the neck).[56] After six weeks, fermentation was complete, and the wine was filtered into larger containers and either sold for consumption or stored in a cellar or cistern, lasting for three to four years.[63][66] Even after a year of aging, the vintage was still called "new wine," and more aged wines were preferred.[66][67][68]

Spices and scents were often added to wine in order to hide "defects" that arose from storage that was often not sufficient to prevent all spoiling.[69] One might expect about 10% of any given cellar of wine to have been ruined completely, but vinegar was also created intentionally for dipping bread[70] among other uses.[71]

Alcoholic content of beverages in the ancient world

[edit]After the conquest of Palestine by Alexander the Great, the Hellenistic custom of diluting wine had taken hold such that the author of 2 Maccabees speaks of diluted wine as "a more pleasant drink" and of both undiluted wine and unmixed water as "harmful" or "distasteful."[72]

Alcoholic wine in the ancient world was significantly different than modern wines in that it had much lower alcohol content and was consumed after significant dilution with water (as attested by even other cultures surrounding Israel), thus rendering its alcoholic content negligible by modern standards.[8][73][10] The low alcoholic content was due to the limitations of fermentation in the ancient world.[11][8] From the Mishnah and Talmuds, the common dilution rate for consumption for Jews 3 parts water to 1 part wine (3:1 dilution ratio).[8] Wine in the ancient world had a maximum possible alcoholic content of 11-12% (before dilution) and once diluted, it reduced to 2.75 or 3%.[8] Other after-dilution estimates of neighbors like the Greeks have dilution of 1:1 or 2:1 which place the alcohol content between 4-7%.[73]

The adjective “unmixed” (ἄκρατος) is used in the ancient texts to designate undiluted wine, but the New Testament never uses this adjective to describe the wine consumed by Jesus, the disciples or to describe the wine approved for use in moderation by Christians.[9] Though ancient rabbis opposed the consumption of undiluted wine as a beverage, they taught that it was useful as a medicine.[9]

Common dilution ratios from the ancient world were compiled by Athenaus of Naucratis in Deipnosophistae (Banquet of the Learned; c. AD 228):[74]

| Ancient source | Dilution Ratio

Water:Wine |

|---|---|

| Homer | 20:1 |

| Pliny | 8:1 |

| Aristophanes | 2 or 3:1 |

| Hesiod | 3:1 |

| Alexis | 4:1 |

| Diocles | 2:1 |

| Ion | 3:1 |

| Nichochares | 5:2 |

| Anacreon | 2:1 |

Alcohol in Christian history and tradition

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Eucharist |

|---|

|

It is not disputed whether the regular use of wine in the celebration of the Eucharist and in daily life were the virtually universal practice in Christianity for over 1,800 years; all written evidence shows that the Eucharist consisted of bread and wine, not grape juice.[75][76] During the 19th and early 20th century, as a general sense of prohibitionism arose, many Christians, particularly some Protestants in the United States, came to believe that the Bible prohibited alcohol or that the wisest choice in modern circumstances was for the Christian to abstain from alcohol willingly.

Before Christ

[edit]

The Hebraic opinion of wine in the time before Christ was decidedly positive: wine is part of the world God created and is thus "necessarily inherently good,"[77] though excessive use is soundly condemned. The Jews emphasized joy in the goodness of creation rather than the virtue of temperance, which the Greek philosophers advocated.[78] Wine formed part of the sacrifices made daily to God. (Leviticus 23:13)

As the Jews returned from the Babylonian exile (starting in 537 BC) and the events of the Old Testament drew to a close, wine was "a common beverage for all classes and ages, including the very young; an important source of nourishment; a prominent part in the festivities of the people; a widely appreciated medicine; an essential provision and the wine that the vineyards produced was a valued commodity in ancient times, both for local consumption and for its value in trade or any fortress; and an important commodity," and it served as "a necessary element in the life of the Hebrews."[79] Wine was also used ritualistically to close the Sabbath and to celebrate weddings, circumcisions, and Passover.[80]

Although some abstentionists argue that wine in the Bible was almost always cut with water greatly decreasing its potency for inebriation,[22] there is general agreement that, while Old Testament wine was sometimes mixed with various spices to enhance its flavor and stimulating properties, it was not usually diluted with water,[81][82] and wine mixed with water is used as an Old Testament metaphor for corruption.[83] Among the Greeks, however, the cutting of wine with water was a common practice used to reduce potency and improve taste.[84] By the time of the writing of 2 Maccabees (2nd or 1st century BC), the Greeks had conquered Judea under Alexander the Great, and the Hellenistic custom had apparently found acceptance with the Jews[85] and was carried into Jewish rituals in New Testament times.[86][87]

Under the rule of Rome, which had conquered Judea under Pompey (see Iudaea Province), the average adult male who was a citizen drank an estimated liter (about a quarter of a gallon, or a modern-day bottle and a third—about 35 oz.) of wine per day,[88] though beer was more common in some parts of the world.[89]

Early Church

[edit]The Apostolic Fathers make very little reference to wine.[90] Clement of Rome (died 100) said: "Seeing, therefore, that we are the portion of the Holy One, let us do all those things which pertain to holiness, avoiding all evil-speaking, all abominable and impure embraces, together with all drunkenness, seeking after change, all abominable lusts, detestable adultery, and execrable pride."[91] The earliest references from the Church Fathers make it clear that the early Church used in the Eucharist wine—which was customarily mixed with water.[92][93] The Didache, an early Christian treatise which is generally accepted to be from the late 1st century, instructs Christians to give a portion of their wine in support of a true prophet or, if they have no prophet resident with them, to the poor.[94]

Clement of Alexandria (died c. 215) wrote in a chapter about drinking that he admired the young and the old who "abstain wholly from drink," who adopt an austere life and "flee as far as possible from wine, shunning it as they would the danger of fire." He strongly warned youth to "flee as far as possible" from it so as not to inflame their "wild impulses." He said Christ did not teach affected by it. "...the soul itself is wisest and best when dry." He also said wine is an appropriate symbol of Jesus' blood.[95][96] He noted taking a little wine as medicine is acceptable—lest it make the health worse. Even those who are "moored by reason and time" (such that they are not as much tempted by drunkenness after a day's work), he still encouraged to mix "as much water as possible" in with the wine to inhibit inebriation. For at all hours, let them keep their "reason unwavering, their memory active, and their body unmoved and unshaken by wine."

Tertullian (died 220) insisted clergy must be sober in church, citing the biblical non-drinking precedent: "the Lord said to Aaron: 'Wine and spirituous liquor shall ye not drink, thou and thy son after thee, whenever ye shall enter the tabernacle, or ascend unto the sacrificial altar; and ye shall not die.' [Lev. 10:9] So true is it, that such as shall have ministered in the Church, being not sober, shall 'die.' Thus, too, in recent times He upbraids Israel: 'And ye used to give my sanctified ones wine to drink.' [Amos 2:12]"[97]

Some early Christian leaders focused on the strength and attributes of wines. They taught that two types of wine should be distinguished: wine causing joyousness and that causing gluttony (intoxicating and non-intoxicating). The hermit John of Egypt (died 395) said: "...if there is any sharp wine I excommunicate it, but I drink the good."[98] Gregory of Nyssa (died 395) made the same distinction between types of wine, "not that wine which produces drunkenness, plots against the senses, and destroys the body, but such as gladdens the heart, the wine which the Prophet recommends".[99]

Condemnation of drunkenness had increased by the late 4th century. Church rules against drinking entertainments are found in the Council of Laodicea (363):[100]

- Rule XXIV: "No one of the priesthood, from presbyters to deacons, and so on in the ecclesiastical order to subdeacons, readers, singers, exorcists, door-keepers, or any of the class of the Ascetics, ought to enter a tavern."

- Rule LV: "NEITHER members of the priesthood nor of the clergy, nor yet laymen, may club together for drinking entertainments."

However, Basil the Great (died 379) repudiated the views of some dualistic heretics who abhorred marriage, rejected wine, and called God's creation "polluted"[101] and who substituted water for wine in the Eucharist.[102]

A minority of Christians abstained totally from alcoholic beverages. Monica of Hippo (died 387) eagerly kept the strict rule of total abstinence, which her bishop Ambrose required. She had never let herself drink much at all, not even "more than one little cup of wine, diluted according to her own temperate palate, which, out of courtesy, she would taste." But now she willingly drank none at all.[103] Augustine cited a reason for her bishop's rule: "even to those who would use it with moderation, lest thereby an occasion of excess might be given to such as were drunken." Ambrose of course expected leaders and deacons to practice the same rule too. He cited Paul's instructions to them about alcohol in 1 Timothy 3:2-4 and 3:8-10, and commented: "We note how much is required of us. The minister of the Lord should abstain from wine, so that he may be upheld by the good witness not only of the faithful but also by those who are without."[104] Likewise, he said: "Let a widow, then, be temperate, pure in the first place from wine, that she may be pure from adultery. He will tempt you in vain, if wine tempts you not."[105]

John Chrysostom (died 407) said: "they who do not drink take no thought of the drunken."[106] So Chrysostom insisted deacons cannot taste wine at all in his homily on 1 Timothy 3:8-10: "The discretion of the blessed Paul is observable. When he would exhort the Deacons to avoid excess in wine, he does not say, 'Be not drunken,' but 'not' even 'given to much wine.' A proper caution; for if those who served in the Temple did not taste wine at all, much more should not these, For wine produces disorder of mind, and where it does not cause drunkenness, it destroys the energies and relaxes the firmness of the soul."[107] Of course he was aware that not all wines were intoxicating; they had opposite effects and were not all alike.[108] His homily on 1 Timothy 5:23 shows he was not as certain heretics and immature Christians who even "blame the fruit given them by God" when saying there should be no wine. He emphasized the goodness of God's creation and adjured: "Let there be no drunkenness; for wine is the work of God, but drunkenness is the work of the devil. Wine makes not drunkenness; but intemperance produces it. Do not accuse that which is the workmanship of God, but accuse the madness of a fellow mortal."[109]

The virtue of temperance passed from Greek philosophy into Christian ethics and became one of the four cardinal virtues under St. Ambrose[110] and St. Augustine.[111][112][113] Drunkenness, on the other hand, is considered a manifestation of gluttony, one of the seven deadly sins as compiled by Gregory the Great in the 6th century.[114]

Middle Ages

[edit]

The decline of the Roman Empire brought with it a significant drop in the production and consumption of wine in western and central Europe, but the Eastern and Western Church (particularly the Byzantines) preserved the practices of viticulture and winemaking.[115]

Vitae Patrum (from the third and fourth centuries) states: "When abba Pastor was told of a certain monk who wouldn't drink wine he replied, 'A monk should have nothing to do with wine.'"[116] "Elias archbishop of Jerusalem [from 494], drank no wine, just as if he were a monk."[117]

Later Benedict of Nursia (died c. 547), who formulated the monastic rules governing the Benedictines, still seems to prefer that monks should do without wine as a daily staple, but he indicates that the monks of his day found the old regulation too burdensome. Thus he offers the concession of a quarter liter (or perhaps, a half liter)[118] of wine per day as sufficient for nourishment, with allowance for more in special circumstances[119] and for none as a punishment for repeated tardiness.[120] Even so, he believes that abstinence is the best path for those who have a gift from God allowing them to restrain their bodily appetites.[121]

Welsh Bishop David (c. 500 – c. 589) was known as "David the water-drinker." He rejected any alcohol. The monasteries he established had water only.[122]

The medieval monks, renowned as the finest creators of beer and wine,[123] were allotted about 5 liters of beer per day, and were allowed to drink beer (but not wine) during fasts.[124][125] This was justified by the Church. Bread and water that made up ale's ingredients was considered to not be a sin like that of wine. Brewing in monasteries increased and a number of modern breweries can trace their origins back to medieval monasteries.[126]

Thomas Aquinas (died 1274), a Dominican friar and the "Doctor Angelicus" of the Catholic Church, says that moderation in wine is sufficient for salvation but that for certain persons perfection requires abstinence, and this was dependent upon their circumstance.[127] With regard to the Eucharist, he says that grape wine should be used and that "must", unlike juice from unripe grapes, qualifies as wine because its sweetness will naturally turn it into wine. So freshly pressed must is indeed usable (preferably after filtering any impurities).[128]

Drinking among monks was not universal, however, and in 1319 Bernardo Tolomei founded the Olivetan Order, initially following a much more ascetic Rule than Benedict's. The Olivetans uprooted all their vineyards, destroyed their wine-presses, and were "fanatical total abstainers," but the rule was soon relaxed.[129]

Because the Catholic Church requires properly fermented wine in the Eucharist,[130] wherever Catholicism spread, the missionaries also brought grapevines so they could make wine and celebrate the Mass.[123] The Catholic Church continues to celebrate a number of early and medieval saints related to alcohol—for instance, St. Adrian, patron saint of beer; St. Amand, patron saint of brewers, barkeepers, and wine merchants; St. Martin, the so-called patron saint of wine; St. Vincent, patron saint of vintners.[123]

Wine has a place in the divine services of the Eastern Orthodox Church, not only in the celebration of the Divine Liturgy (Eucharist), but also at the artoklassia (blessing of bread, wine, wheat and oil during the All Night Vigil) and in the "common cup" of wine which is shared by the bride and groom during an Orthodox wedding service. A small amount of warm wine (zapivka) is taken by the faithful together with a piece of antidoron after receiving Holy Communion. In the Serbian Orthodox Church wine is used in the celebration of a service known as the Slava on feast days. The fasting rules of the Orthodox Church forbid the consumption of wine (and by extension, all alcoholic beverages) on most fast days throughout the year. The Orthodox celebrate St. Tryphon as the patron saint of vines and vineyard workers.[131] "Of course, no events have been found in the life of the saint that show a special relationship among him and vineyard or wine."[132]

Reformation

[edit]The Waldensians made wine but avoided drunkenness.[133] Zwingli reformed Zurich in many ways; in 1530 he reduced the closing time of taverns to 9 pm.[134] He warned: "Let every youth flee from intemperance as he would from a poison ... it makes furious the body, ... it brings on premature old age."[135] The monks under the Papacy refused to abstain from drinking: this astonished Calvin. He said they merely abstained from certain foods instead. He contrasted them against the dignified Nazarites and the priests who were forbidden the use of wine in the Jewish Temple.[136] With Calvin at Geneva, "Low taverns and drinking shops were abolished, and intemperance diminished."[137] However, Calvin's annual salary in Geneva included seven barrels of wine.[138]

The Lutheran Formula of Concord (1576)[139] and the Reformed Christian confessions of faith[140][141][142][143] make explicit mention of and assume the use of wine, as does the 1689 Baptist Confession of Faith.[144] In the Dordrecht Confession of Faith (1632), even the radical Anabaptists, who sought to expunge every trace of Roman Catholicism and to rely only on the Bible, also assumed wine was to be used,[145] and despite their reputation as killjoys,[146] the English Puritans were temperate partakers of "God's good gifts," including wine and ale.[147]

Colonial America

[edit]As the Pilgrims set out for America, they brought a considerable amount of alcohol with them for the voyage (more than 28,617 liters = 7,560 gallons, or 4 litres/person/day),[148] and once settled, they served alcohol at "virtually all functions, including ordinations, funerals, and regular Sabbath meals."[149] M. E. Lender summarizes the "colonists had assimilated alcohol use, based on Old World patterns, into their community lifestyles" and that "[l]ocal brewing began almost as soon as the colonists were safely ashore."[150] Increase Mather, a prominent colonial clergyman and president of Harvard, expressed the common view in a sermon against drunkenness: "Drink is in itself a good creature of God, and to be received with thankfulness, but the abuse of drink is from Satan; the wine is from God, but the drunkard is from the Devil."[151] This Old World attitude is likewise found among the early Methodists (Charles Wesley, George Whitefield, Adam Clarke,[152] Thomas Coke) and Baptists (John Gill and John Bunyan).

Methodism

[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Methodism |

|---|

|

|

|

At the time that Methodist founder John Wesley lived, "alcohol was divided between 'ardent spirits,' which included whisky, rum, gin, and brandy, and fermented drinks, such as wine, cider, and beer."[153] In a sermon he warned: "You see the wine when it sparkles in the cup, and are going to drink of it. I tell you there is poison in it! and, therefore, beg you to throw it away".[154] In an early letter to his mother Susanna, he simply dismissed those who thought she was unusual and too restrictive to have but one glass of wine.[155] In a series of letters dated to 1789, he noted that experiments prove "ale without hops will keep just as well as the other"—thus he directly contradicted claims by vested interests, whom he likened to the pretentious silversmiths who stirred up violence: 'Sir, by this means we get our wealth.' (Acts 19:25). He rejected their claims of wholesomeness for this poisonous herb.[156] Wesley, beyond many in his era, deplored distilled beverages such as brandy and whisky when they were used non-medicinally, and he said the many distillers who sold indiscriminately to anyone were nothing more than poisoners and murderers accursed by God.[157] In 1744, the directions the Wesleys gave to the Methodist band societies (small groups of Methodists intended to support living a holy life) required them "to taste no spirituous [i.e., distilled] liquor ... unless prescribed by a physician."[158]

Early advocacy for abstentionism in Methodism arose in America. At the 1780 Methodist Episcopal Church Conference in Baltimore, the churchmen opposed distilled liquors and determined to "disown those who would not renounce the practice" of producing it.[159] In opposing liquors, the American Methodists anticipated the first wave of the temperance movement that would follow.[159] They expanded their membership rule regarding alcohol to include other alcoholic beverages over the next century. Despite pressure from interested parties to relax rules of all kinds, the American Methodists afterwards reverted to Wesley's—namely, to avoid "[d]runkenness, buying or selling spirituous [i.e., distilled] liquors, or drinking them, unless in cases of extreme necessity".[160]

Bishops in America Thomas Coke and Francis Asbury commented that frequent fasting and abstinence are "highly necessary for the divine life."[161] Asbury strongly urged citizens to lay aside the use of alcohol.[162] Likewise, the listed duties for Methodist preachers indicate that they should choose water as their common drink and use wine only in medicinal or sacramental contexts,[163] Methodist Bible commentator Adam Clarke held that the fruit of the vine at the Last Supper was pure and incomparable to what some think of as wine today.[164]

Wesley's Articles of Religion, adopted by the Methodist Episcopal Church (a precursor of the United Methodist Church) in 1784, rejected the doctrine of transubstantiation of elements in the Lord's Supper (Article XVIII), and said the use of both bread and the cup together extends to all the people (Article XIX), not only one element for laymen and two for ministers as in the Catholic practice of the time.[165]

Adam Clarke explained 1 Cor. 11:21-22: "One was hungry, and the other was drunken, μεθυει, was filled to the full; this is the sense of the word in many places of Scripture."[166] Likewise, Coke and Asbury commented on it saying Paul's objection here concerned the Corinthians (including laymen) and "... their both eating and drinking most intemperately" thereby despising the Church of God and shaming those who have nothing.[167]

Later, British Methodists, in particular the Primitive Methodists, took a leading role in the temperance movement in Britain during the 19th and early-20th centuries. Methodists saw alcoholic beverages, and alcoholism, as the root of many social ills and tried to persuade people to abstain from these.[168] Temperance appealed strongly to the Methodist doctrines of sanctification and perfection. This continues to be reflected in the teaching of certain Methodist denominations today. For example, ¶91 of the 2014 Discipline of the Allegheny Wesleyan Methodist Connection states:[169]

We believe total abstinence from all intoxicating liquors as a beverage to be the duty of all Christians. We heartily favor moral suasion and the gospel remedy to save men from the drink habit. We believe that law must be an adjunct of moral means in order to suppress the traffic side of this evil. We believe that the State and the citizen each has solemn responsibilities and duties to perform in regard to this evil. We believe that for the State to enact any law to license or tax the traffic, or derive revenues therefrom, is contrary to the policy of good government, and brings the State into guilty complicity with the traffic and all the evils growing out of it, and is also unscriptural and sinful in principle and ought to be opposed by every Christian and patriot. We therefore believe that the only true and proper remedy for the gigantic evil of the liquor traffic is its entire suppression; and that all our people and true Christians everywhere should pray and vote against this evil, and not suffer themselves to be controlled by or support political parties which are managed in the interest of the drink traffic.[169]

However, in the mainline British Methodist Church, the Commission on Methodism and Total Abstinence in 1972 reported that only 30% of ministers affirmed their total abstention from alcohol. Discerning merits in both abstinent and non-abstinent perspectives, the report proposed evaluating alcohol concerns within the broader context of other drug-related issues. In a subsequent report to the Methodist Conference in 1987 titled "Through a Glass Darkly", a more extensive reconsideration of attitudes was undertaken; it recommended that Methodists commit to either total abstinence or responsible drinking (moderationism).[170] The 2000 Methodist Conference re-affirmed the church's position on personal consumption and the prohibition of alcohol supply, sale or use on Methodist premises (except private residences).[171]

Temperance movement

[edit]In the midst of the social upheaval accompanying the American Revolution and urbanization induced by the Industrial Revolution, drunkenness was on the rise and was blamed as a major contributor to the increasing poverty, unemployment, and crime. Yet the temperate sentiments of the Methodists were shared only by a few others, until the publication of a tract by eminent physician and patriot Benjamin Rush, who argued against the use of "ardent spirits" (i.e., distilled alcohol), introduced the notion of addiction, and prescribed abstinence as the only cure.[172][173] Some prominent preachers like Lyman Beecher picked up on Rush's theme and galvanized the temperance movement to action. Though losing influence during the American Civil War, afterward the movement experienced its second wave, spearheaded by the Women's Christian Temperance Union, and it was so successful in achieving its goals that Catherine Booth, co-founder of the Salvation Army, could observe in 1879 that in America "almost every [Protestant] Christian minister has become an abstainer."[174] The movement saw the passage of anti-drinking laws in several states and peaked in its political power in 1919 with the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which established prohibition as the law of the entire country but which was repealed in 1933 by the Twenty-first Amendment.

Initially the vast majority of the temperance movement had opposed only distilled alcohol,[175] which they saw as making drunkenness inexpensive and easy, and espoused moderation and temperance in the use of other alcoholic beverages. Fueled in part by the Second Great Awakening, which emphasized personal holiness and sometimes perfectionism, the temperance message changed to the outright elimination of alcohol.[176][177][178][179]

Consequently, alcohol itself became an evil in the eyes of many (but not all) abstainers and so had to be expunged from Christian practice—especially from the holy rite of the Lord's Supper.[177][180] The use of a grape-based drink other than wine for the Lord's Supper took a strong hold in many churches, including American Protestantism, though some churches had detractors who thought wine was to be given strong preference in the rite. Some denominational statements required "unfermented wine" for the Lord's Supper. For example, the Wesleyan Methodists (since founded 1843, some fifty years after Wesley's death) required "unfermented wine".[181]

Since grape juice begins naturally fermenting upon pressing, opponents of wine utilized alternate methods of creating their ritual drink such as reconstituting concentrated grape juice, boiling raisins, or adding preservatives to delay fermenting and souring.[182] In 1869, Thomas Bramwell Welch, an ordained Wesleyan Methodist minister,[183] discovered a way to pasteurize grape juice, and he used his particular preservation method to prepare juice for the Lord's Supper at a Methodist Episcopal church.

From 1838 to 1845, Father Mathew, the Irish apostle of temperance, administered an abstinence pledge to some three to four million of his countrymen, though his efforts had little permanent effect there, and then starting in 1849 to more than 500,000 Americans, chiefly his fellow Irish Catholics, who formed local temperance societies but whose influence was limited. In 1872 the Catholic Total Abstinence Union of America united these societies and by 1913 reached some 90,000 members including the juvenile, women's, and priestly contingents. The Union pursued a platform of "moral suasion" rather than legislative prohibition and received two papal commendations. In 1878 Pope Leo XIII praised the Union's determination to abolish drunkenness and "all incentive to it," and in 1906 Pope Pius X lauded its efforts in "persuading men to practise one of the principal Christian virtues — temperance."[184] By the time the Eighteenth Amendment was up for consideration, however, Archbishop Messmer of Milwaukee denounced the prohibition movement as being founded on an "absolutely false principle" and as trying to undermine the Church's "most sacred mystery," the Eucharist, and he forbade pastors in his archdiocese from assisting the movement but suggested they preach on moderation.[185] In the end, Catholicism was largely unaffected in doctrine and practice by the movements to eliminate alcohol from church life,[186][187] and it retained its emphasis on the virtue of temperance in all things.[188]

Similarly, while the Lutheran and Anglican churches felt some pressure, they did not alter their moderationist position. Even the English denominational temperance societies refused to make abstention a requirement for membership, and their position remained moderationist in character.[189] It was non-Lutheran Protestantism from which the temperance movement drew its greatest strength.[190][191] Many Methodists, Presbyterians,[192][193] and other Protestants signed on to the prohibitionist platform.

The 1881 assembly of the United Presbyterian Church of North America said "the common traffic in, and the moderate use of intoxicants as a beverage are the source of all these evils."[194] In 1843, the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America's general assembly (generally considered part of the conservative Old School) considered and narrowly rejected making the selling of alcoholic beverages grounds for excommunication from the church.[195]

The Quakers (Religious Society of Friends) came to be a strong influence for the temperance cause.[196] By the 1830s, Quakers were in agreement with the dominant moral philosophy of this era in regarding distilling spirits as sinful while accepting beer brewing.[197][198] Several prominent Quaker families in this era were involved in large London breweries.[197][199]

The legislative and social effects resulting from the temperance movement peaked in the early 20th century and began to decline afterward.[200] The effects on church practice were primarily a phenomenon in American Protestantism and to a lesser extent in the British Isles, the Nordic countries, and a few other places.[191][201] The practice of the Protestant churches were slower to revert, and some bodies, though now rejecting their formerly prohibitionist platform, still retain vestiges of it such as using grape juice alone or beside wine in the Lord's Supper.

Current views

[edit]Today, the views on alcohol in Christianity can be divided into moderationism, abstentionism, and prohibitionism. Abstentionists and prohibitionists are sometimes lumped together as "teetotalers", sharing some similar arguments. However, prohibitionists abstain from alcohol as a matter of law (that is, they believe God requires abstinence in all ordinary circumstances), while abstentionists abstain as a matter of prudence (that is, they believe total abstinence is the wisest and most loving way to live in the present circumstances).[12]

Some groups of Christians fall entirely or virtually entirely into one of these categories, while others are divided between them. Fifty-two percent of Evangelical leaders around the world say drinking alcohol is incompatible with being a good Evangelical. Even now, nominally "Christian" countries still have 42% who say it is incompatible.[202]

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union is an ecumenical Christian organization with members from various denominational backgrounds that work together to promote teetotalism.[203] Within the Catholic Church, the Pioneer Total Abstinence Association is a teetotal temperance organization that requires of its members complete abstinence from alcoholic drink as an expression of devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus.[204]

Moderationism

[edit]The moderationist position is held by Roman Catholics[205] and Eastern Orthodox,[206] and within Protestantism, it is accepted by Anglicans,[17] Lutherans[207][208] and many Reformed churches.[209][210][211][212] Moderationism is also accepted by Jehovah's Witnesses.[213]

Moderationism argues that, according to the biblical and traditional witness, (1) alcohol is a good gift of God that is rightly used in the Eucharist and for making the heart merry, and (2) while its dangers are real, it may be used wisely and moderately rather than being shunned or prohibited because of potential abuse.[76][177][214][215] Moderationism holds that temperance (that is, moderation or self-control) in all of one's behavior, not abstinence, is the biblical norm.[216][217]

On the first point, moderationists reflect the Hebrew mindset that all creation is good.[218] The ancient Canons of the Apostles, which became part of Canon Law in the eastern and western Churches, likewise allows Church leaders and laity to abstain from wine for mortification of the flesh but requires that they not "abominate" or detest it, which attitude "blasphemously abuses" the good creation.[219] Going further, John Calvin says that "it is lawful to use wine not only in cases of necessity, but also thereby to make us merry,"[220] and in his Genevan Catechism, he answers that wine is appropriate in the Lord's Supper because "by wine the hearts of men are gladdened, their strength recruited, and the whole man strengthened, so by the blood of our Lord the same benefits are received by our souls."[221]

On the second point, Martin Luther employs a reductio ad absurdum to counter the idea that abuse should be met with disuse: "[W]e must not ... reject [or] condemn anything because it is abused ... [W]ine and women bring many a man to misery and make a fool of him (Ecclus. 19:2; 31:30); so [we would need to] kill all the women and pour out all the wine."[222] In dealing with drunkenness at the love feast in Corinth,[55] St. Paul does not require total abstinence from drink but love for one another that would express itself in moderate, selfless behavior.[223][224] However, moderationists approve of voluntary abstinence in several cases, such as for a person who finds it too difficult to drink in moderation and for the benefit of the "weaker brother," who would err because of a stronger Christian exercising their liberty to drink.[225]

While all moderationists approve of using (fermented) wine in the Eucharist in principle (Catholics, the Orthodox, and Anglicans require it),[130][226] because of prohibitionist heritage and a sensitivity to those who wish to abstain from alcohol, many offer either grape juice or both wine and juice at their celebrations of the Lord's Supper.[207][210][211][227] Some Christians mix some water with the wine following ancient tradition, and some attach a mystical significance to this practice.[228][229]

Comparison

[edit]In addition to lexical and historical differences,[214][230] moderationism holds that prohibitionism errs by confusing the Christian virtues of temperance and moderation with abstinence and prohibition and by locating the evil in the object that is abused rather than in the heart and deeds of the abuser.[16][177] Moreover, moderationists suggest that the prohibitionist and abstentionist positions denigrate God's creation and his good gifts and deny that it is not what goes into a man that makes him evil but what comes out (that is, what he says and does).[48][231] The Bible never uses the word 'wine' of communion. Yet moderationists hold that in banishing wine from communion and dinner tables, prohibitionists and abstentionists go against the 'witness of the Bible' and the church throughout the ages and implicitly adopt a Pharisaical moralism that is at odds with what moderationists consider the right approach to biblical ethics and the doctrines of sin and sanctification.[215][232][233]

Abstentionism

[edit]The abstentionist position is held by many Baptists,[234] Methodists,[235] Nazarenes, Pentecostals,[236] and other evangelical Protestant groups including the Salvation Army.[237] Prominent proponents of abstentionism include Billy Graham,[238] John F. MacArthur,[239] R. Albert Mohler, Jr.,[240] and John Piper.[241]

Abstentionists believe that although alcohol consumption is not inherently sinful or necessarily to be avoided in all circumstances, it is generally not the wisest or most prudent choice.[242] Many abstentionists do not require abstinence from alcohol for membership in their churches, though they do often require it for leadership positions (as with many Baptist churches), while other abstentionist denominations require abstinence from alcohol for all their members, both clergy and laypersons (as with the Bible Methodist Connection of Churches).[26][241][243][244]

Some reasons commonly given for voluntary abstention are:

- The Bible warns that alcohol can hinder moral discretion. Proverbs 31:4-5 warns kings and rulers that they might "forget what is decreed, and pervert the rights of all the afflicted." Some abstentionists speak of alcohol as "corrupt[ing]" the body and as a substance that can "impair my judgment and further distract me from God's will for my life."[245]

- Christians must be sensitive to the "weaker brother", that is, the Christian who believes imbibing to be a sin. On this point MacArthur says, "[T]he primary reason I don't do a lot of things I could do, including drinking wine or any alcoholic beverage, [is] because I know some believers would be offended by it ... [M]any Christians will drink their beer and wine and flaunt their liberty no matter what anyone thinks. Consequently, there is a rift in the fellowship."[246]

- Christians should make a public statement against drunkenness because of the negative consequences it can have on individuals, families, and society as a whole. Some abstentionists believe that their witness as persons of moral character is also enhanced by this choice.[243][245]

Additionally, abstentionists argue that while drinking may have been more acceptable in ancient times (for instance, using wine to purify polluted drinking water),[26][247] modern circumstances have changed the nature of a Christian's responsibility in this area. First, some abstentionists argue that wine in biblical times was weaker and diluted with water such that drunkenness was less common,[248][249] though few non-abstentionists accept this claim as wholly accurate[81] or conclusive.[217] Also, the invention of more efficient distillation techniques has led to more potent and cheaper alcohol, which in turn has lessened the economic barrier to drinking to excess compared to biblical times.[250]

Comparison

[edit]On historical and lexical grounds, many abstentionists reject the argument of prohibitionists that wine in the Bible was not alcoholic and that imbibing is nearly always a sin.[24][26] Piper summarizes the abstentionist position on this point:

- The consumption of food and drink is in itself no basis for judging a person's standing with God ... [The Apostle Paul's] approach to these abuses [of food and drink] was never to forbid food or drink. It was always to forbid what destroyed God's temple and injured faith. He taught the principle of love, but did not determine its application with regulations in matters of food and drink.[251]

Abstentionists also reject the position of moderationists that in many circumstances Christians should feel free to drink for pleasure because abstentionists see alcohol as inherently too dangerous and not "a necessity for life or good living,"[22][243] with some even going so far as to say, "Moderation is the cause of the liquor problem."[243]

Prohibitionism

[edit]Most Laestadian Pietist Lutheran congregations ("Finnish Lutherans"), such as the First Apostolic Lutheran Church, dominated by Finns in Michigan and Minnesota, are ambivalently against alcoholic consumption, as the Church has roots as a temperance movement in Finland. During the U.S. Prohibition movement during the early twentieth century, many Finnish Lutherans were elected to Congress, propelling the earliest stages towards the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.[252]

Certain Methodist denominations, such as the Evangelical Methodist Church Conference and Allegheny Wesleyan Methodist Connection, teach prohibitionism.[253][169]

In the Seventh-day Adventist Church, members must also abide by a health code that includes not drinking alcohol or consuming any other recreational drugs.[254][255] North American Adventist health study recruitments from 2001-2007 found that 93.4% of Adventists abstained from drinking alcohol, 98.9% were non-smokers, and only 54% ate meat.[256] Studies have also shown that Adventist members are healthier and live longer. Dan Buettner has named Loma Linda, California a "Blue Zone" of longevity, and attributes that to the large concentration of Seventh-day Adventists and their health practices.[257][258]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the largest body of the Latter Day Saint movement, teaches that "God has spoken against the use of ... [a]lcohol". The church's leaders base this teaching on a revelation received by the prophet Joseph Smith called the Word of Wisdom.[259][260]

Influential organizations

[edit]

Other prohibitionist organizations advocate for the cause prohibition but do not require their members to follow the rule,[261][262] and the prohibitionist position has experienced a general reduction of support since the days of the temperance movement and prohibitionism, with many advocates instead becoming abstentionists.[200][citation needed]

The Southern Baptist Convention resolved that their "churches be urged to give their full moral support to the prohibition cause, and to give a more liberal financial support to dry organizations which stand for the united action of our people against the liquor traffic."[263][264][265] Influential Baptist preacher Charles Spurgeon wrote: "I wish the man who made the law to open them had to keep all the families that they have brought to ruin. Beer shops are the enemies of the home; therefore, the sooner their licenses are taken away, the better."[266][267]

The founder of The Salvation Army[237] William Booth was a prohibitionist, and saw alcohol as evil in itself and not safe for anyone to drink in moderation.[268] In 1990, the Salvation Army re-affirms: "It would be inconsistent for any Salvationist to drink while at the same time seeking to help others to give it up."[269]

David Wilkerson founder of the Teen Challenge rehabilitation organization, said similar things to Assemblies of God: "a little alcohol is too much since drinking in moderation provides Satan an opening to cruel deception."[270][271]

Billy Sunday, an influential evangelical Christian, said: "After all is said that can be said on the liquor traffic, its influence is degrading on the individual, the family, politics and business and upon everything that you touch in this old world."[272]

Bible interpretations

[edit]Prohibitionists such as Stephen Reynolds[273][274][275] and Jack Van Impe[276] hold that the Bible forbids partaking of alcohol altogether, with some arguing that the alleged medicinal use of wine in 1 Timothy 5:23 is a reference to unfermented grape juice.[21] They argue that the words for alcoholic beverages in the Bible can also refer to non-alcoholic versions such as unfermented grape juice, and for this reason the context must determine which meaning is required.[20][275] In passages where the beverages are viewed negatively, prohibitionists understand them to mean the alcoholic drinks, and where they are viewed positively, they understand them to mean non-alcoholic drinks.[277]

Prohibitionists also accuse most Bible translators of exhibiting a bias in favor of alcohol that obscures the meaning of the original texts.[21][275]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jesus Christ. "Matthew 26:29;Mark 14:25;Luke 22:18".

I tell you, I will not drink from this fruit of the vine from now on until that day when I drink it new with you in my Father's kingdom.

- ^ R. V. Pierard (1984). "Alcohol, Drinking of". In Walter A. Elwell (ed.). Evangelical Dictionary of Theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House. pp. 28f. ISBN 0-8010-3413-2.

- ^ F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone, ed. (2005). "Wine". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press, USA. p. 1767. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

[W]ine has traditionally been held to be one of the essential materials for a valid Eucharist, though some have argued that unfermented grape-juice fulfils the Dominical [that is, Jesus'] command.

- ^ Domenico, Roy P.; Hanley, Mark Y. (1 January 2006). Encyclopedia of Modern Christian Politics. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-313-32362-1.

Drunkenness was biblically condemned, and all denominations disciplined drunken members.

- ^ Cobb, John B. (2003). Progressive Christians Speak: A Different Voice on Faith and Politics. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-664-22589-6.

For most of Christian history, as in the Bible, moderate drinking of alcohol was taken for granted while drunkenness was condemned.

- ^ Raymond, p. 90.

- ^ a b c d e "Wine". Easton's Bible Dictionary. 1897. Retrieved 2007-01-22.

- ^ a b c d e f Quarles, Charles L. (23 July 2021). "Was New Testament Wine Alcoholic?". Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary.

First, ancient beverages did not contain distilled alcohol like modern alcoholic beverages often do. Distillation was invented by Arab alchemists in the 8th century long after the New Testament era. The strongest alcoholic beverage that was accessible to the New Testament authors and their original readers was natural wine that had an alcoholic content of 11-12% (before dilution). Second, ancient wine was normally diluted. Even ancient pagans considered drinking wine full strength to be a barbaric practice. They typically diluted wine with large amounts of water before the wine was consumed. A careful study of the Mishnah and Talmuds shows that the normal dilution rate among the Jews was 3 parts water to 1 part wine...This dilution rate reduces the alcohol content of New Testament wine to 2.75 to 3.0% ...Certainly, it was fermented and had a modest alcohol content. But the alcohol content was negligible by modern standards.

- ^ a b c d Quarles, Charles L. (28 July 2021). "Does Approval of the Use of New Testament Wine Justify Use of Modern Alcoholic Beverages?". Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary.

When the ancients referred to undiluted wine, they specified this by adding the adjective "unmixed" (ἄκρατος) which indicated that the wine had not been poured into the krater, the large mixing bowl where the wine and water were combined (Rev 14:10; Jer 32:15 LXX; Ps 74:9 LXX; Ps. Sol 8:14). The New Testament never uses this adjective to describe the wine consumed by Jesus and the disciples or to describe the wine approved for use in moderation by Christians. New Testament wine is typically heavily diluted wine...Ancient rabbis clearly prohibited consumption of undiluted wine as a beverage. Some rabbis prohibited reciting the normal blessing over wine at mealtime "until one puts water into it so that it may be drunk" (m. Ber. 7:4–5). The rabbis of the Talmud taught that undiluted wine was useful only for the preparation of medicines (b. Ber. 50b; cf. b. Nid 67b; 69b).

- ^ a b Vallee, Bert L. (June 1, 2015). "The Conflicted History of Alcohol in Western Civilization". Scientific American.

The beverages of ancient societies may have been far lower in alcohol than their current versions, but people of the time were aware of the potentially deleterious behavioral effects of drinking. The call for temperance began quite early in Hebrew, Greek and Roman cultures and was reiterated throughout history. The Old Testament frequently disapproves of drunkenness, and the prophet Ezra and his successors integrated wine into everyday Hebrew ritual, perhaps partly to moderate undisciplined drinking, thus creating a religiously inspired and controlled form of prohibition.

- ^ a b Sasson, Jack M. "The Blood of Grapes: Viticulture and Intoxication in the Hebrew Bible." Drinking in Ancient Societies; History and Culture of Drinks in the Ancient Near East. Ed. Lucio Milano. Padua: Sargon srl, 1994. 399-419. "Here is the third point: Israel, as did its neighbors, probably manufactured brandy, liqueurs and cordials by perfuming, flavoring, or sweetening its wines; and such products may too have fallen under the term 'sekar', but until the Hellenistic period there is no direct evidence that it distilled them to raise their alcoholic content. The only method our documents know about raising the alcoholic level is to augment the sugar content of grapes by drying them in the sun before they are processed for fermentation. It is possible that the same result was obtained by boiling mashed pulp; in either case, however, the wine of Hebrew carousers was relatively mild alcoholically; and to fully earn the condemnations of Hebrew prophets and moralists, revellers must drink hard and long."

- ^ a b Gentry, Kenneth (2001). God Gave Wine. Oakdown. pp. 3ff. ISBN 0-9700326-6-8.

- ^ Campbell, Ted A. (1 December 2011). Methodist Doctrine: The Essentials. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-1-4267-1364-4.

Prohibition: Methodists supported efforts for the prohibition of alcoholic beverages as a social extension of their concern for temperance or abstinence

- ^ Miller, Stephen M. (15 April 2014). 100 Tough Questions about God and the Bible. Baker Academic. p. 225. ISBN 9781441263520.

Most, however, preach moderation: Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran, and Eastern Orthodox.

- ^ a b Waltke, Bruce (2005). "Commentary on 20:1". The Book of Proverbs: Chapters 15-31. Wm. B. Eerdmans. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-8028-2776-0.

• Fitzsimmonds, F. S. (1982). "Wine and Strong Drink". In Douglas, J. D. (ed.). New Bible Dictionary (2nd ed.). Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press. p. 1255. ISBN 0-8308-1441-8.These two aspects of wine, its use and its abuse, its benefits and its curse, its acceptance in God's sight and its abhorrence, are interwoven into the fabric of the [Old Testament] so that it may gladden the heart of man (Ps. 104:15) or cause his mind to err (Is. 28:7), it can be associated with merriment (Ec. 10:19) or with anger (Is. 5:11), it can be used to uncover the shame of Noah (Gn. 9:21) or in the hands of Melchizedek to honour Abraham (Gn. 14:18) ... The references [to alcohol] in the [New Testament] are very much fewer in number, but once more the good and the bad aspects are equally apparent ...

• McClintock, James; Strong, James (1891). "Wine (eds.)". Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature. Vol. X. New York: Harper and Brothers. p. 1016.But while liberty to use wine, as well as every other earthly blessing, is conceded and maintained in the Bible, yet all abuse of it is solemnly condemned.

- ^ a b Raymond, I. W. (1970) [1927]. The Teaching of the Early Church on the Use of Wine and Strong Drink. AMS Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-404-51286-6.

This favourable view [of wine in the Bible], however, is balanced by an unfavourable estimate ... The reason for the presence of these two conflicting opinions on the nature of wine [is that the] consequences of wine drinking follow its use and not its nature. Happy results ensue when it is drunk in its proper measure and evil results when it is drunk to excess. The nature of wine is indifferent.

- ^ a b c Ethical Investment Advisory Group (January 2005). "Alcohol: An inappropriate investment for Anglicanism" (PDF). Church of England. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-02-26. Retrieved 2007-02-08.

Christians who are committed to total abstinence have sometimes interpreted biblical references to wine as meaning unfermented grape juice, but this is surely inconsistent with the recognition of both good and evil in the biblical attitude to wine. It is self-evident that human choice plays a crucial role in the use or abuse of alcohol.

- ^ Fitzsimmonds, pp. 1254f.

- ^ Reynolds, Stephen M. (1989). The Biblical Approach to Alcohol. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

[W]herever oinos [Greek for 'wine'] appears in the New Testament, we may understand it as unfermented grape juice unless the passage clearly indicates that the inspired writer was speaking of an intoxicating drink.

• "Stuart, Moses". Encyclopedia of Temperance and Prohibition. New York: Funk and Wagnalls. 1891. p. 621.Wherever the Scriptures speak of wine as a comfort, a blessing or a libation to God, and rank it with such articles as corn and oil, they mean—they can mean only—such wine as contained no alcohol that could have a mischievous tendency; that wherever they denounce it, prohibit it and connect it with drunkenness and reveling, they can mean only alcoholic or intoxicating wines.

Quoted in Reynolds, The Biblical Approach to Alcohol. - ^ a b Earle, Ralph (1986). "1 Timothy 5:13". Word Meanings in the New Testament. Kansas City, Missouri: Beacon Hill Press. ISBN 0-8341-1176-4.

Oinos is used in the Septuagint for both fermented and unfermented grape juice. Since it can mean either one, it is valid to insist that in some cases it may simply mean grape juice and not fermented wine.

•

• Lees, Frederic Richard; Dawson Burns (1870). "Appendix C-D". The Temperance Bible-Commentary. New York: National Temperance Society and Publishing House. pp. 431–446.

• Patton, William (1871). "Christ Eating and Drinking". Laws of Fermentation and the Wines of the Ancients. New York: National Temperance Society and Publishing House. p. 85. Retrieved 2008-03-25.Oinos is a generic word, and, as such, includes all kinds of wine and all stages of the juice of the grape, and sometimes the clusters and even the vine ...

• McLauchlin, G. A. (1973) [1913]. Commentary on Saint John. Salem, Ohio: Convention Book Store H. E. Schmul. p. 32.There were ... two kinds of wine. We have no reason to believe that Jesus used the fermented wine unless we can prove it ... God is making unfermented wine and putting in skin cases and hanging it upon the vines in clusters every year.

- ^ a b c Bacchiocchi, Samuele. "A Preview of Wine in the Bible". Archived from the original on 2007-02-02. Retrieved 2007-01-22.

- ^ a b c MacArthur, John. "Living in the Spirit: Be Not Drunk with Wine--Part 2". Retrieved 2007-01-22.

- ^ Ewing, W. (1913). "Wine". In James Hastings (ed.). Dictionary of Christ and the Gospels. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: T & T Clark. p. 824. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

There is nothing known in the East of anything called 'wine' which is unfermented ... [The Palestinian Jews'] attitude towards the drinker of unfermented grape juice may be gathered from the saying in Pirke Aboth (iv. 28), 'He who learns from the young, to what is he like? to one who eats unripe grapes and drinks wine from his vat [that is, unfermented juice].'

(Emphasis in original.)

• Hodge, Charles (1940) [1872]. "The Lord's Supper". Systematic Theology. Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 3:616. Retrieved 2007-01-22.That [oinos] in the Bible, when unqualified by such terms as new, or sweet, means the fermented juice of the grape, is hardly an open question. It has never been questioned in the Church, if we except a few Christians of the present day. And it may safely be said that there is not a scholar on the continent of Europe, who has the least doubt on the subject.

• Hodge, A. A. Evangelical Theology. p. 347f.'Wine,' according to the absolutely unanimous, unexceptional testimony of every scholar and missionary, is in its essence 'fermented grape juice.' Nothing else is wine ... There has been absolutely universal consent on this subject in the Christian Church until modern times, when the practice has been opposed, not upon change of evidence, but solely on prudential considerations.

Quoted in Mathison, Keith (January 8–14, 2001). "Protestant Transubstantiation - Part 3: Historic Reformed & Baptist Testimony". IIIM Magazine Online. 3 (2). Retrieved 2007-01-22. - ^ a b Beecher, W. J. "Total abstinence". The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. p. 472. Retrieved 2007-01-22.

The Scriptures, rightly understood, are thus the strongest bulwark of a true doctrine of total abstinence, so false exegesis of the Scriptures by temperance advocates, including false theories of unfermented wine, have done more than almost anything else to discredit the good cause. The full abandonment of these bad premises would strengthen the cause immeasurably.

- ^ William Kaiser and Duane Garrett, ed. (2006). "Wine and Alcoholic Beverages in the Ancient World". Archaeological Study Bible. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-92605-4.

[T]here is no basis for suggesting that either the Greek or the Hebrew terms for wine refer to unfermented grape juice.

- ^ a b c d MacArthur, John F. "GC 70-11: "Bible Questions and Answers"". Retrieved 2007-01-22.

• Pierard, p. 28: "No evidence whatsoever exists to support the notion that the wine mentioned in the Bible was unfermented grape juice. When juice is referred to, it is not called wine (Gen. 40:11). Nor can 'new wine' ... mean unfermented juice, because the process of chemical change begins almost immediately after pressing." - ^ Dommershausen, W. (1990). "Yayin". In G. Johannes Botterweck and Helmer Ringgren (ed.). Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament. Vol. VI. trans. David E. Green. Wm. B. Eerdmans. p. 64. ISBN 0-8028-2330-0.

- ^ Raymond, p. 24: "The numerous allusions to the vine and wine in the Old Testament furnish an admirable basis for the study of its estimation among the people at large."

- ^ Ge 27:28; 49:9-12; Dt 7:13; 11:14; 15:14; compare 33:28; Pr 3:9f; Jr 31:10-12; Ho 2:21-22; Jl 2:19,24; 3:18; Am 9:13f; compare 2Ki 18:31-32; 2Ch 32:28; Ne 5:11; 13:12; etc.

- ^ Pr 20:1

- ^ Ps 60:3; 75:8; Is 51:17-23; 63:6; Jr 13:12-14; 25:15-29; 49:12; 51:7; La 4:21f; Ezk 23:28-33; Na 1:9f; Hab 2:15f; Zc 12:2; Mt 20:22; 26:39, 42; Lk 22:42; Jn 18:11; Re 14:10; 16:19; compare Ps Sol 8:14

- ^ Jg 9:13; Ps 4:7; 104:15; Ec 9:7; 10:19; Zc 9:17; 10:7

- ^ "Drunkenness". Illustrated Dictionary of Bible Life & Times. Pleasantville, New York: The Reader's Digest Association. 1997. pp. 374–376.

- ^ Six pots of thirty-nine liters each = 234 liters = 61.8 gallons, according to Seesemann, Heinrich (1967). "οινος". In Kitte, Gerhard; Pitkin, Ronald E. (eds.). Theological Dictionary of the New Testament. Vol. V. Translated by Bromiley, Geoffrey W. Wm. B. Eerdmans. p. 163. ISBN 0-8028-2247-9.

- ^ Jn 2:1-11; 4:46

- ^ Mt 26:17-19; Mk 14:12-16; Lk 22:7-13. The Gospel of John offers some difficulties when compared with the Synoptists' accounts on whether the meal was part of the Passover proper. In any case, it seems that the Last Supper was most likely somehow associated with Passover, even if it was not the paschal feast itself. See the discussion in Morris, Leon (1995). "Additional Note H: The Last Supper and the Passover". The Gospel According to John. New International Commentary on the New Testament (revised ed.). Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 684–695. ISBN 978-0-8028-2504-9.

- ^ Seesemann, p. 162: "Wine is specifically mentioned as an integral part of the passover meal no earlier than Jub. 49:6 ['... all Israel was eating the flesh of the paschal lamb, and drinking the wine ...'], but there can be no doubt that it was in use long before." P. 164: "In the accounts of the Last Supper the term [wine] occurs neither in the Synoptists nor Paul. It is obvious, however, that according to custom Jesus was proffering wine in the cup over which He pronounced the blessing; this may be seen especially from the solemn [fruit of the vine] (Mark 14:25 and par.) which was borrowed from Judaism." Compare "fruit of the vine" as a formula in the Mishnah, "Tractate Berakoth 6.1". Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- ^ Raymond, p. 80: "All the wines used in basic religious services in Palestine were fermented."

- ^ Mt 26:26-29; Mk 14:22-25; Lk 22:17-20; 1 Co 10:16; 11:23-25

- ^ Lincoln, Bruce (2005). "Beverages". In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). MacMillan Reference Books. p. 848. ISBN 978-0-02-865733-2.

- ^ Pr 31:4-7; Mt 27:34,48; Mk 15:23,36; Lk 23:36; Jn 19:28–30

- ^ Lk 10:34

- ^ 1 Ti 5:23

- ^ Pr 31:4f; Lv 10:9; compare Ez 44:21

- ^ Compare Lk 1:15.

- ^ Nu 6:2-4 (compare Jg 13:4-5; Am 2:11f); Jr 35

- ^ Mt 11:18f; Lk 7:33f; compare Mk 14:25; Lk 22:17f

- ^ a b I. W. Raymond p. 81: "Not only did Jesus Christ Himself use and sanction the use of wine but also ... He saw nothing intrinsically evil in wine.[footnote citing Mt 15:11 ]"

- ^ Ro 14:21.Raymond understands this to mean that "if an individual by drinking wine either causes others to err through his example or abets a social evil which causes others to succumb to its temptations, then in the interests of Christian love he ought to forego the temporary pleasures of drinking in the interests of heavenly treasures" (p. 87).

- ^ Posner, Rabbi Menachem. "What is Judaism's take on alcohol consumption? - Questions & Answers".

Even today, [Jewish] priests may not bless the congregation after having even a single glass of wine.

- ^ For instance, Pr 20:1; Is 5:11f; Ho 5:2,5; Ro 13:13; Ep 5:18; 1 Ti 3:2-3.

- ^ Ge 9:20-27

- ^ Ge 19:31-38

- ^ Broshi, Magen (1984). "Wine in Ancient Palestine — Introductory Notes". Israel Museum Journal. III: 33.

- ^ a b 1Co 11:20-22

- ^ a b Ewing, p. 824.

- ^ See Broshi, passim (for instance, p. 29: Palestine was "a country known for its good wines").

- ^ Compare 2Ch 2:3,10

- ^ Gately, Iain (2008). Drink: a Cultural History of Alcohol (1st ed.). New York: Gotham Books. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-592-40464-3.

- ^ Ps 80:8-15; Is 5:1f; Mk 12:1; compare SS 2:15

- ^ Sefer Kedushah, MaAchalot Assurot, Ch. 11, Halacha 11

- ^ Compare Is 16:10; Jr 48:33

- ^ a b c "Wine Making". Illustrated Dictionary of Bible Life & Times. pp. 374f.

- ^ Broshi, p. 24.

- ^ Dt 16:13-15

- ^ a b Broshi, p. 26.

- ^ Lk 5:39; compare Is 25:6

- ^ Dommershausen, pp. 60-62.

- ^ Broshi, p. 27.

- ^ Ru 2:14

- ^ Broshi, p. 36.

- ^ 2 Maccabees 15:40

- ^ a b "Alcohol consumption - Alcohol and society". Encyclopedia Britannica.

The Greco-Roman classics abound with descriptions of drinking and often of drunkenness. The wine of the ancient Greeks, like that of the Hebrews of the same time, was usually drunk diluted with an equal part or two parts of water, and so the alcohol strength of the beverage was presumably between 4 and 7%.

- ^ Quarles, Charles L. (23 July 2021). "Was New Testament Wine Alcoholic?". Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary. "One of the most helpful discussions of dilution rates appears in a work by Athenaus of Naucratis called Deipnosophistae (Banquet of the Learned; c. AD 228). Athenaus mentions several different dilution rates that he culled from ancient works."

- ^ Bingham, Joseph (1720). Origines Ecclesiasticæ: Or, The Antiquities of the Christian Church. Retrieved 2014-08-20.

'The Canons had also a great Respect to the external and publick Behaviour of the Clergy; obliging them to walk circumspectly, and abstain from things of ill Fame, though otherwise innocent and indifferent in themselves; that they might cut off all Occasions of Obloquy, by avoiding all suspicious Actions and All Appearances of Evil. In regard to which they not only censured them for Rioting and Drunkenness (which were vices not to be tolerated even in laymen) but forbad them to so much as eat or appear in a publick Inn or Tavern, except they were upon a Journey, or some such necessary Occasion required them to do it under Pain of ecclesiastical censure. The Council of Laodecia [b] and the third council of Carthage [c] forbid it universally to all Orders of the Clergy; and the Apostolic Canons [d] more expressly, with a Denunciation of Censure...'

- ^ a b Mathison, Keith (December 4–10, 2000). "Protestant Transubstantiation - Part 1: Thesis; Biblical Witness". IIIM Magazine Online. 2 (49). Retrieved 2007-01-22.

- ^ Raymond, p. 48.

- ^ Raymond, p. 49.

- ^ Hanson, David J. (1995). Preventing Alcohol Abuse: Alcohol, Culture and Control. Westport, CT: Praeger. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-275-94926-6.

• Broshi, Magen (1986). "The Diet of Palestine in the Roman Period — Introductory Notes". Israel Museum Journal. V: 46.In the biblical description of the agricultural products of the Land, the triad 'cereal, wine, and oil' recurs repeatedly (Deut. 28:51 and elsewhere). These were the main products of ancient Palestine, in order of importance. The fruit of the vine was consumed both fresh and dried (raisins), but it was primarily consumed as wine. Wine was, in antiquity, an important food and not just an embellishment to a feast ... Wine was essentially a man's drink in antiquity, when it became a significant dietary component. Even slaves were given a generous wine ration. Scholars estimate that in ancient Rome an adult consumed a liter of wine daily. Even a minimal estimate of 700g. per day means that wine constituted about one quarter of the caloric intake (600 out of 2,500 cal.) and about one third of the minimum required intake of iron.

• Raymond, p. 23: "[Wine] was a common beverage for all classes and ages, even for the very young. Wine might be part of the simpelest meal as well as a necessary article in the households of the rich.

• Geoffrey Wigoder; et al., eds. (2002). "Wine". The New Encyclopedia of Judaism. New York University Press. pp. 798f. ISBN 978-0-8147-9388-6.As a beverage, it regularly accompanied the main meal of the day. Wherever the Bible mentions 'cup' — for example, 'my cup brims over' (Ps. 23:5)—the reference is to a cup of wine ... In the talmudic epoch ... [i]t was customary to dilute wine before drinking by adding one-third water. The main meal of the day, taken in the evening (only breakfast and supper were eaten in talmudic times), consisted of two courses, with each of which a cup of wine was drunk.

- ^ Wigoder, p. 799.

- ^ a b Gentry, God Gave Wine, pp. 143-146: "[R]ecognized biblical scholars of every stripe are in virtual agreement on the nondiluted nature of wine in the Old Testament."

- ^ Clarke, commentary on Is 1:22: "It is remarkable that whereas the Greeks and Latins by mixed wine always understood wine diluted and lowered with water, the Hebrews on the contrary generally mean by it wine made stronger and more inebriating by the addition of higher and more powerful ingredients, such as honey, spices, defrutum, (or wine inspissated by boiling it down to two-thirds or one- half of the quantity,) myrrh, mandragora, opiates, and other strong drugs."

- ^ Is 1:22

- ^ Rayburn, Robert S. (2001-01-28). "Revising the Practice of the Lord's Supper at Faith Presbyterian Church No. 2, Wine, No. 1". Archived from the original on 2012-10-15. Retrieved 2012-04-03.

- ^ Dommershausen, p. 61: "The custom of drinking wine mixed with water—probably in the ratio of two or three to one—seems to have made its first appearance in the Hellenistic era."

• Archaeological Study Bible.Wine diluted with water was obviously considered to be of inferior quality (Isa.1:22), although the Greeks, considering the drinking of pure wine to be an excess, routinely diluted their wine.

• Raymond, p.47: "The regulations of the Jewish banquets in Hellenistic times follow the rules of Greek etiquette and custom."

• Compare 2 Mac 15:39[usurped] (Vulgate numbering: 2 Mac 15:40) - ^ Compare the later Jewish views described in "Wine". Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ^ Unger, Merrill F. (1981) [1966]. "Wine". Unger's Bible Dictionary (3rd ed.). Chicago: Moody Press. p. 1169.

The use of wine at the paschal feast [that is, Passover] was not enjoined by the law, but had become an established custom, at all events in the post-Babylonian period. The wine was mixed with warm water on these occasions.... Hence in the early Christian Church it was usual to mix the sacramental wine with water.

- ^ Broshi, p. 33.

- ^ Broshi, p. 22.

- ^ Raymond, p. 88.

- ^ Clement of Rome. "Letter to the Corinthians". Archived from the original on 2017-12-07. Retrieved 2014-08-20.

- ^ Justin Martyr, First Apology, "Chapter LXV. Administration of the sacraments" and "Chapter LXVII. Weekly worship of the Christians".

- ^ Hippolytus of Rome (died 235) says, "By thanksgiving the bishop shall make the bread into an image of the body of Christ, and the cup of wine mingled with water according to the likeness of the blood." Quoted in Mathison, Keith (January 1–7, 2001). "Protestant Transubstantiation - Part 2: Historical Testimony". IIIM Magazine Online. 3 (1). Retrieved 2007-01-22.

- ^ "Didache, chapter 13". Archived from the original on May 28, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ^ Clement of Alexandria. "On Drinking". The Instructor, book 2, chapter 2. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- ^ Compare the summary in Raymond, pp. 97-104.

- ^ Tertullian. "On Fasting, Ch. 9., From Fasts Absolute Tertullian Comes to Partial Ones And Xerophagies".

- ^ Palladius. ""Life of the Holy Fathers", Ch. XXXV".

- ^ Gregory of Nyssa (395). "Funeral Oration on Meletius".

- ^ "Synod of Laodicea". Archived from the original on 2017-01-06.

- ^ Basil the Great (1895). "Letter CXCIX: To Amphilochius, concerning the Canons". Basil: Letters and Select Works. Philip Schaff (ed.). Retrieved 2008-04-16.

- ^ Allert, Craig D. (1999). "The State of the New Testament Canon in the Second Century: Putting Tatian's Diatessaron in Perspective" (PDF). Bulletin for Biblical Research (9): 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-11. Retrieved 2008-04-16.

Also among the beliefs of the [heretical] Encratites is the rejection of the drinking of wine. In fact, the Encratites even went so far as to substitute water for wine in the Eucharist service.

- ^ Augustine. ""Confessions", Book VI, Ch. 2".

- ^ Ambrose, "On the Duties of the Clergy", Ch. 50, section 256

- ^ Ambrose, "Concerning Widows", Ch. 7, section 40

- ^ Chrysostom, John. "Homilies on the Gospel of St. Matthew". pp. Homily LVII. Archived from the original on 2017-06-10. Retrieved 2014-08-19.

- ^ Chrysostom, John. "Homilies on the First Epistle of St. Paul to Timothy, Homily XI, 1 Timothy 3:8-10".

- ^ Chrysostom. "Homilies on Ephesians, Homily XIX, Ephesians v. 15, 16, 17".

Like his contemporaries, Chrysostom distinguished between types of wine, saying 'it cannot be that one and the same thing should work opposite effects.'

- ^ Chrysostom, John. "First Homily on the Statues". pp. paras 11f. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- ^ Ambrose. "Book I, chapter XLIII". On the Duties of the Clergy. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- ^ Augustine. "Augustine: The Writings Against the Manichaeans and Against the Donatists, Book XXII, Ch. 44".