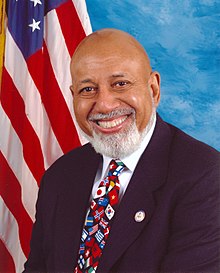

Alcee Hastings

Alcee Hastings | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Florida | |

| In office January 3, 1993 – April 6, 2021 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Sheila Cherfilus-McCormick |

| Constituency | 23rd district (1993–2013) 20th district (2013–2021) |

| Judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida | |

| In office November 2, 1979 – October 20, 1989 | |

| Appointed by | Jimmy Carter |

| Preceded by | Seat established |

| Succeeded by | Federico A. Moreno |

| Judge of the 17th Judicial Circuit Court of Florida | |

| In office May 2, 1977 – October 31, 1979 | |

| Appointed by | Reubin Askew |

| Preceded by | Stewart LaMotte |

| Succeeded by | Harry Hinckley |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Alcee Lamar Hastings September 5, 1936 Altamonte Springs, Florida, U.S. |

| Died | April 6, 2021 (aged 84) |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Twice divorced Patricia Williams (m. 2019) |

| Children | 4 |

| Education | Fisk University (BA) Howard University Florida A&M University (JD) |

Alcee Lamar Hastings (/ˈælsiː/ AL-see; September 5, 1936 – April 6, 2021) was an American politician and former judge from the state of Florida.

Hastings was nominated to the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida by President Jimmy Carter in August 1979. He was confirmed by the United States Senate on October 31, 1979. In 1981, after an FBI sting operation, Hastings was charged with conspiracy to solicit a bribe. Following a 1983 criminal trial, Hastings was acquitted; however, he was impeached for bribery and perjury by the United States House of Representatives in 1988 and was convicted by the United States Senate in his impeachment trial on October 20, 1989. While Hastings was removed from the bench, the Senate did not bar him from holding public office in the future. Hastings was the first and, as of 2024, remains the only African American federal official to be impeached.

A Democrat, Hastings was first elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1992, serving until his death in 2021. His district, numbered as the 23rd district from 1993 to 2013 and the 20th district from 2013 until his death, included most of the majority-black precincts in and around Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach. Following Ileana Ros-Lehtinen's departure from office in 2019, Hastings became the dean of Florida's congressional delegation; he retained this title until his death.[1]

Early life, education, and early career

[edit]Alcee Lamar Hastings was born in Altamonte Springs, Florida, the son of Mildred L. (Merritt) and Julius "J. C." Hastings.[2][3] He was educated at Crooms Academy in Goldsboro (Sanford), Florida, before going on to attend Howard University in Washington, D.C., and Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee.[4] He earned his Bachelor of Arts degree in zoology and botany from Fisk in 1958.[4] After being dismissed from Howard University School of Law,[5] Hastings received his Juris Doctor from Florida A&M University College of Law in 1963.[4] While in school, he became a member of the Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity. He was admitted to the bar in 1963, and began to practice law.[4]

Hastings participated in civil rights demonstrations, and was jailed six times during such events. As a lawyer, Hastings filed suit after being denied a room at a hotel due to segregation policies.[2]

1970 U.S. Senate election

[edit]Hastings decided to run for the United States Senate in 1970 after incumbent Spessard Holland decided to retire. He failed to win the Democratic primary or make the runoff election, finishing fourth out of five candidates, with 13% of the vote. Former Governor Farris Bryant finished first with 33% of the vote. State Senator Lawton Chiles was second with 26%. Chiles defeated Bryant in the runoff election and won the November general election.[6]

Judicial career (1977–1989)

[edit]

In 1977, Hastings became a judge of the circuit court of Broward County, Florida.[5] On August 28, 1979, President Jimmy Carter nominated Hastings to the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida.[7] He was confirmed by the United States Senate on October 31, 1979, and received his commission on November 2, 1979.[8] Hastings was the first black federal judge in the history of the state of Florida.[5] His service was terminated on October 20, 1989, due to impeachment and conviction.[7]

Allegations and impeachment

[edit]Criminal trial

[edit]In 1981, after a sting operation by the FBI against attorney and alleged co-conspirator William Borders,[9] Hastings was charged with conspiracy to solicit a $150,000 bribe (equivalent to $502,709 in 2023) in exchange for a lenient sentence for Frank and Thomas Romano on 21 counts of racketeering and the return of their seized assets.[10] In his 1983 trial, Hastings was acquitted by a jury after Borders refused to testify in court, despite having been convicted in his own trial in 1982.[9] Borders went to jail for accepting the first $25,000 payment, but was later given a full pardon by President Bill Clinton on his last day in office.[11]

Impeachment trial

[edit]The Judicial Conference of the United States investigated Hastings and brought its accusations, which it believed warranted an impeachment, to the United States House of Representatives. It concluded that Hastings had perjured himself and falsified evidence in order to obtain his acquittal, and that he had in fact conspired to gain financially by accepting bribes.[12][13][14]

In 1988, the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives took up the case, and Hastings was impeached for bribery and perjury by a vote of 413–3. He was then convicted in his impeachment trial before the United States Senate on October 20, 1989. At the time, the Senate was also controlled by a Democratic majority. Hastings became the sixth federal judge in the history of the United States to be removed from office by the Senate. The Senate, in two hours of roll calls, voted on 11 of the 17 articles of impeachment. It convicted Hastings of eight of the 11 articles. The vote on the first article was 69 for and 26 opposed.[15] He was removed from the bench, but the Senate did not preclude him from holding office in the future.[16] FBI examiner William Tobin later stated that some FBI testimony presented to Congress misrepresented or misstated forensic analysis he conducted, although he agreed with the overall FBI forensic assessment against Hastings. Tobin's work centered on a purse strap and whether it was strong enough to be snapped accidentally, which related to an alibi Hastings had given for being with Borders. The FBI analysis, supported by Tobin, concluded that the strap had been deliberately cut, inferring that Hastings did so to concoct his alibi.[13]

Appeal

[edit]Hastings filed suit in federal court claiming that his impeachment trial was invalid because he was tried by a Senate committee, not in front of the full Senate, and that he had been acquitted in a criminal trial. Judge Stanley Sporkin ruled in favor of Hastings, remanding the case to the Senate, but stayed his ruling pending the outcome of an appeal to the Supreme Court in a similar case regarding Judge Walter Nixon, who had also been impeached and removed.[17]

The Supreme Court ruled in Nixon v. United States, again referring to Walter Nixon, that procedures for trying an impeached individual cannot be subject to review by the judiciary. Judge Sporkin changed his ruling accordingly, and Hastings's conviction and removal were upheld.[18]

1990 Secretary of State election

[edit]Hastings attempted to make a political comeback by running for Secretary of State of Florida, campaigning on a platform of legalizing casinos. In a three-way Democratic primary, he placed second with 33% of the vote, behind newspaper columnist Jim Minter's 38% of the vote. In the runoff, which saw a large drop-off in turnout, Minter defeated Hastings, 67%–33%. Hastings won just one of Florida's 67 counties, namely Dade County.[19]

U.S. House of Representatives (1993–2021)

[edit]Elections

[edit]Hastings was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1992, representing Florida's 23rd district. After placing second in the initial Democratic primary for the post, he scored an upset victory over state representative Lois J. Frankel in the runoff, and went on to easily win election in the heavily Democratic district. He did not face a serious challenge for reelection thereafter. Following redistricting, Hastings represented Florida's 20th district from January 2013 until his death.[20][21] His death triggered a special election in 2022.

Tenure

[edit]Hastings was a member of the Congressional Black Caucus[22] and was elected president of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe in July 2004. As a senior Democratic whip, Hastings was an influential member of the Democratic leadership. He was also a member of the House Rules Committee. He was previously a senior member of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI). On the HPSCI, Hastings was the chairman of the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations.[23]

Impeachment matters

[edit]In September 1998, Hastings introduced an unsuccessful resolution to impeach Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr.[24] On September 11, 1998, Hastings was one of 63 House members to vote against a resolution to publicly release the Starr Report into Democratic Party President Bill Clinton's conduct and authorize a House Judiciary Committee review of the report.[25] On October 8, 1998, Hastings joined all but 31 Democratic House members in voting against the authorization of the impeachment inquiry against Clinton.[26] On December 9, 1998, Hastings joined nearly all Democrats in voting against all four articles of impeachment introduced against Clinton, two of which were successfully approved by the House.[27] Also on December 19, 1998, Hastings joined nearly all Democrats in voting against the appointment of impeachment managers.[28] On January 6, 1999, he joined nearly all Democrats in voting against the re-appointment of the impeachment managers at the start of the 106th United States Congress.[29]

Hastings voted to impeach Texas federal judge Samuel B. Kent on all four counts presented against him on June 19, 2009.[30]

On March 11, 2010, Hastings took part in the unanimous votes to approve all four articles of impeachment against Federal Judge Thomas Porteous.[31]

On October 31, 2019, Hastings joined nearly all Democrats in voting for a resolution directing how several committee should proceed in the then-ongoing impeachment inquiry into President Donald Trump, a Republican.[32] On December 18, 2019, he joined nearly all Democrats in voting to impeach Trump.[33] On January 13, 2021, he joined all Democrats and ten Republicans in voting to impeach Trump for a second time.[34]

Objection to the 2000 presidential election

[edit]Hastings and other members of the House of Representatives objected to counting the 25 electoral votes from Florida which George W. Bush narrowly won after a contentious recount. Because no senator joined his objection, the objection was dismissed by Vice President Al Gore, who was Bush's opponent in the 2000 presidential election.[35]

Objection to the 2004 presidential election

[edit]Hastings was one of the 31 House Democrats who voted not to count the 20 electoral votes from Ohio in the 2004 presidential election, despite Republican President George W. Bush winning the state by 118,457 votes.[36][37] Without Ohio's electoral votes, the election would have been decided by the U.S. House of Representatives, with each state having one vote in accordance with the Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Bid for chairmanship of the House Intelligence Committee

[edit]After the 2006 United States House of Representatives elections, Hastings attracted attention after it was reported that incoming House Speaker Nancy Pelosi might appoint him as head of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. He had support from the Congressional Black Caucus but was opposed by the Blue Dog Coalition. Hastings attacked his critics as "misinformed fools." Pelosi reportedly favored Hastings over the ranking Democrat, Jane Harman, due to policy differences and the Congressional Black Caucus's support.[38] On November 28, 2006, Pelosi announced that Hastings would not be the committee's chairman,[39] and she later chose Silvestre Reyes (D-TX). While Hastings was passed over to chair the committee, he became chair of a subcommittee. He told the National Journal, "I am not angry. At some point along the way, it became too much to explain. That is legitimate politics. But it's unfortunate for me."[40]

Comments about Sarah Palin

[edit]On September 24, 2008, Hastings came under fire for comments he made about Republican vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin. Speaking in Washington, D.C., to a conference sponsored by the National Jewish Democratic Council, he said, "If Sarah Palin isn't enough of a reason for you to get over whatever your problem is with Barack Obama, then you damn well had better pay attention. Anybody toting guns and stripping moose don't care too much about what they do with Jews and blacks. So, you just think this through."[41]

On September 29, 2008, Hastings issued a written apology, while standing by its core message: "I regret the comments I made last Tuesday that were not smart and certainly not relevant to hunters or sportsmen. The point I made, and will continue to make, is that the policies and priorities of a McCain-Palin administration would be anathema to most African Americans and Jews. I regret that I was not clearer and apologize to Governor Palin, my host where I was speaking, and those who my comments may have offended."[42]

Lexus lease

[edit]In May 2009, The Wall Street Journal reported that Hastings spent over $24,000 in taxpayer money in 2008 to lease a luxury Lexus hybrid sedan. The Journal noted that the expenditure was legal, properly accounted for, and drawn from an expense allowance the U.S. government grants to all lawmakers.[43]

Sexual harassment allegation

[edit]In June 2011, one of Hastings's staff members, Winsome Packer, filed a lawsuit alleging that he had made repeated unwanted sexual advances and threatened her job when she refused him.[44] A congressional ethics panel investigated these claims.[44] Packer was represented by the conservative legal group Judicial Watch. Hastings denied the allegations and called them "ludicrous."[45] He said, "I will win this lawsuit. That is a certainty. In a race with a lie, the truth always wins. And when the truth comes to light and the personal agendas of my accusers are exposed, I will be vindicated."[46] In February 2012, it was reported that Hastings would be released from the lawsuit, and it would only continue against the Helsinki Commission which Hastings chaired and Packer represented in Vienna.[47] In December 2017, it was reported that the Treasury Department paid $220,000 to settle the lawsuit.[48] Hastings later complained that he played no role in the settlement negotiations but the way they had been framed implied that he had.[49]

Improper relationship investigation

[edit]Hastings was investigated by the House Ethics Committee in 2019 over his relationship with then-girlfriend and Congressional deputy district director Patricia Williams. Williams, Hastings' girlfriend of over 25 years, was the highest paid staffer in Hastings' office. For nearly a decade, she received greater compensation than her superior, Hastings' chief of staff, typically the highest paid role in a Congressional office. Williams' compensation was at the maximum for Congressional staffers and exceeded the compensation of every other deputy district director in Congress except one. The investigation sought to uncover whether the relationship violated a 2018 House nepotism rule against members engaging in sexual relationships with staffers.[50][51][52]

The Ethics Committee dropped its investigation after saying that Hastings had married Williams in 2019, as the rule did not prohibit spousal relationships with staffers, although it did not clarify why Hastings' alleged conduct prior to 2019, well after the rule was in place, was not subject to repercussions from the committee.[51][52]

Committee assignments

[edit]- Committee on Rules (Vice Chair)

- Helsinki Commission (chair)

Leadership positions

[edit]- Florida Congressional delegation (co-chairman)

- Senior Democratic whip

- Congressional Caucus on Global Road Safety (co-chairman)

- International Conservation Caucus

- Sportsmen's Caucus

Caucus memberships

[edit]- Congressional Arts Caucus[53]

- Afterschool Caucuses[54]

- Congressional NextGen 9-1-1 Caucus[55]

- United States Congressional International Conservation Caucus[56]

- Veterinary Medicine Caucus[57]

- U.S.-Japan Caucus[58]

- Medicare for All Caucus

- Blue Collar Caucus

Political positions

[edit]Foreign policy

[edit]Hastings opposed President Donald Trump's decision to recognize Jerusalem as Israel's capital. He stated: "I believe that Jerusalem is and should remain the undivided capital of Israel. To deny the Jewish connection to Jerusalem would be to deny world history. That being said, the manner in which the Trump Administration has announced its recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel is of great concern."[59]

Gun policy

[edit]Hastings said that gun control is a "critical element" in addressing the United States' crime problem.[60] He favored reinstating the Federal Assault Weapons Ban and supported a federal ban on bump stocks. He supported raising the minimum age to buy a rifle from 18 to 21. In 2017, he voted against the Concealed Carry Reciprocity Act of 2017. His last rating from the NRA Political Victory Fund was an F, indicating that the organization believed that he did not support gun rights legislation.[61][62][63]

Following the 2018 Stoneman Douglas High School shooting, Hastings released a statement in which he said, "The stranglehold of the gun lobby has gone on long enough."[64] Hastings wrote a letter to the Speaker of the Florida House and President of the Florida Senate urging them to repeal the state's preemption law, which prohibits communities in Florida from passing their own gun regulations.[65]

Personal life and death

[edit]Hastings was married three times and had three children from his first two marriages, as well as one stepchild; his first two marriages ended in divorce. He married Patricia Williams in 2019, and they remained together until his death.[2][14]

In January 2019, Hastings was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, and he died from the disease on April 6, 2021, at the age of 84.[66][67] After his death, his campaign account made a $23,000 expenditure to Williams with no listed campaign purpose.[68]

See also

[edit]- List of African-American federal judges

- List of African-American jurists

- List of African-American United States representatives

- List of United States Congress members who died in office (2000–)#2020s

References

[edit]- ^ Wu, Nicholas (April 6, 2021). "Rep. Alcee Hastings dies at 84 after cancer fight". POLITICO. Retrieved November 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c Smith, Harrison. "Rep. Alcee Hastings, civil rights lawyer and judge elected to 15 terms in Congress, dies at 84". Washington Post. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

By one account, he was born Alcea Lamar Merritt in Altamonte Springs, a farming town north of Orlando, on Sept. 5, 1936. According to the Miami Herald, he changed the spelling of his first name early on and adopted his stepfather's last name, Hastings.

- ^ "Mildred Hastings Obituary (2004) - San Diego, CA - San Diego Union-Tribune". www.legacy.com. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Congressional Directory 2005–2006: One Hundred Ninth Congress, p. 68.

- ^ a b c Robertson, Linda (April 6, 2021). "Alcee Hastings, pioneering civil rights activist, judge and politician, dies at 84". Tampa Bay Times.

- ^ "Our Campaigns – FL US Senate – D Primary Race". www.ourcampaigns.com. September 8, 1970.

- ^ a b U.S. Senate. "The Impeachment Trial of Alcee L. Hastings (1989) U.S. District Judge, Florida". Senate.gov. Washington, D.C.: Historian of the United States Senate. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ^ Alcee Hastings at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- ^ a b "Alcee Hastings trial: Money, the mob and the FBI". Palm Beach Post. May 23, 2019. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ "THE JUDGMENT OF ALCEE HASTINGS AFTER HE WAS AXQUITTED, THE REAL TRIAL BEGAN. NOW CONGRESS MUST DECIDE: IS THE JUDGE A CROOK, OR IS HIS CHARACTER UMIMPEACHABLE?". South Florida Sun Sentinel. January 25, 1987. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ "The Power of the Pardon". Law.com. July 15, 2011. Archived from the original on February 16, 2009. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ^ Volcansek, Mary L. (1990). "British Antecedents for U.S. Impeachment Practices: Continuity and Change" (PDF). The Justice System Journal. 14 (1): 40–62. doi:10.1080/23277556.1990.10871115. ISSN 0098-261X. JSTOR 27976725. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- ^ a b "FBI Role in Impeachment Probed". The Washington Post. February 25, 1997.

- ^ a b Seelye, Katharine Q. (April 6, 2021). "Alcee Hastings, Longtime Florida Congressman, Dies at 84". The New York Times. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ^ Senate Removes Hastings, The Washington Post, October 21, 1989. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ^ U.S. Senate. "The Impeachment Trial of Alcee L. Hastings (1989) U.S. District Judge, Florida". Senate.gov. Washington, D.C.: Historian of the United States Senate. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

Having achieved the necessary majority vote to convict on 8 articles, the Senate's president pro tempore (Robert C. Byrd) ordered Hastings removed from office. The Senate did not vote to disqualify him from holding future office.

- ^ "Senate Conviction of Hastings Is Reversed by Judge Sporkin". The Washington Post. September 18, 1992. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ^ Hastings v. U.S. 837 F.Supp. 3 (1993).

- ^ "Our Campaigns – FL Secretary of State – D Runoff Race". Our Campaigns. October 2, 1990.

- ^ "Florida's 20th Congressional District election, 2016". Ballotpedia. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Florida's 20th Congressional District election, 2018". Ballotpedia. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- ^ "Membership". Congressional Black Caucus. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ "NBCSL'S STATEMENT ON THE PASSING OF CONGRESSMAN ALCEE HASTINGS". National Black Caucus of State Legislators. April 7, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2023.

- ^ "H.Res.545 - Impeaching Kenneth W. Starr, an independent counsel of the United States appointed pursuant to 28 United States Code section 593(b), of high crimes and misdemeanors". Congress.gov. United States Congress. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Two sources:

- "Roll Call 425 Roll Call 425, Bill Number: H. Res. 525, 105th Congress, 2nd Session". Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives. September 11, 1998. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- "H.Res.525 - Providing for a deliberative review by the Committee on the Judiciary of a communication from an independent counsel, and for the release thereof, and for other purposes". Congress.gov. United States Congress.

- ^ "Roll Call 498 Roll Call 498, Bill Number: H. Res. 581, 105th Congress, 2nd Session". Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives. October 8, 1998. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Multiple sources:

(Miller, Lorraine C. (December 19, 1998). "Final vote results for roll call 543". Office of the Clerk. Archived from the original on January 6, 2010. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- Miller, Lorraine C. (December 19, 1998). "Final vote results for roll call 544". Office of the Clerk. Archived from the original on March 2, 2010. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- Miller, Lorraine C. (December 19, 1998). "Final vote results for roll call 545". Office of the Clerk. Archived from the original on March 2, 2010. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- Miller, Lorraine C. (December 19, 1998). "Final vote results for roll call 546". Office of the Clerk. Archived from the original on March 2, 2010. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ "Roll Call 547 Roll Call 547, Bill Number: H. Res. 614, 105th Congress, 2nd Session". Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives. December 19, 1998. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ "Roll Call 6 Roll Call 6, Bill Number: H. Res. 10, 106th Congress, 1st Session". Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives. January 6, 1999. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. House of Representatives Roll Call Votes". United States House of Representatives. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- "Roll Call 102 Roll Call 102, Bill Number: H. Res. 1031, 111th Congress, 2nd Session". Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives. March 11, 2010. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- "Roll Call 102 Roll Call 103, Bill Number: H. Res. 1031, 111th Congress, 2nd Session". Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives. March 11, 2010. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- "Roll Call 102 Roll Call 104, Bill Number: H. Res. 1031, 111th Congress, 2nd Session". Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives. March 11, 2010. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- "Roll Call 102 Roll Call 105, Bill Number: H. Res. 1031, 111th Congress, 2nd Session". Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives. March 11, 2010. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "Roll Call 604 Roll Call 604, Bill Number: H. Res. 660, 116th Congress, 1st Session". Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives. October 31, 2019. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Panetta, Grace. "WHIP COUNT: Here's which members of the House voted for and against impeaching Trump". Business Insider.

- ^ Swasey, Benjamin; Carlsen, Audrey (January 13, 2021). "The House Has Impeached Trump Again. Here's How House Members Voted". NPR.org. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ "Objections Aside, a Smiling Gore Certifies Bush". Los Angeles Times. January 7, 2001. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ "Final Vote Results for Roll Call 7: On Agreeing to the Objection". U.S. House of Representatives. January 6, 2005. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- ^ Salvato, Albert (December 29, 2004). "Ohio Recount Gives a Smaller Margin to Bush". The New York Times. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ Battle of Hastings adds to Pelosi drama MSNBC, November 16, 2006.

- ^ Pelosi Shuts Hastings Out of Intel Chairmanship NPR, November 28, 2006.

- ^ "How the House voted on H.R. 404". November 4, 2020.

- ^ Anderson, Rigel (September 24, 2008). "Florida Congressman: Palin 'Don't Care Too Much What They Do With Jews and Blacks' – Political Radar". ABC News. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ "Black Florida congressman apologizes for Palin comments". CNN. September 29, 2008. Archived from the original on March 24, 2010. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ Radnofsky, Louise; Farnam, T.W. (May 30, 2009). "Lawmakers Bill Taxpayers For TVs, Cameras, Lexus". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on June 8, 2009. Retrieved June 15, 2009.

- ^ a b Fields, Gary; Mullins, Brody (June 22, 2011). "Florida Congressman Faces New Ethics Review". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ^ McCormack, Simon (June 22, 2011). "Alcee Hastings Sexual Harassment Allegation Investigated By Ethics Panel". The Huffington Post. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ^ "Winsome Packer Claims Alcee Hastings Harassment in Lawsuit". LA Late News. March 10, 2011.

- ^ "Alcee Hastings Released From Personal Liability In Sexual Harassment Lawsuit". The Huffington Post. February 14, 2012. Archived from the original on February 16, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ^ Akin, Stephanie (December 9, 2017). "Exclusive: Taxpayers Paid $220K to Settle Case Involving Rep. Alcee Hastings". Roll Call. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- ^ Kindy, Kimberly; Lee, Michelle Ye Hee. "How a congressional harassment claim led to a secret $220,000 payment" – via The Washington Post.

- ^ "Rep. Alcee Hastings, who faces House ethics probe, paid his girlfriend more than his chief of staff". CNBC. November 22, 2019.

- ^ a b "Ethics probe into Alcee Hastings ends after disclosure he married aide". Politico. June 12, 2020.

- ^ a b "Hastings cleared by Ethics Committee". Roll Call. June 12, 2020.

- ^ "Membership". Congressional Arts Caucus. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- ^ "Members". Afterschool Alliance. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ^ "Members". Congressional NextGen 9-1-1 Caucus. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "Our Members". U.S. House of Representatives International Conservation Caucus. Archived from the original on August 1, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ "Members of the Veterinary Medicine Caucus". Veterinary Medicine Caucus. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ^ "Members". U.S. - Japan Caucus. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- ^ "Florida reaction to Trump's recognition of Jerusalem as capital of Israel". Tampa Bay Times. December 6, 2017.

- ^ "Gun Control". U.S. Congressman Alcee L. Hastings. U.S. Federal Government. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- ^ "NRA-PVF | Florida". NRA-PVF. Archived from the original on November 4, 2014. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ "NRA-PVF | Florida". NRA-PVF. Archived from the original on November 3, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Daugherty, Alex (February 20, 2018). "Where South Floridians in Congress stand on gun legislation". Miami Herald. Miami, Florida. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- ^ "Statement on Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Shooting". U.S. Congressman Alcee L. Hastings. February 14, 2018. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- ^ "Hastings Urges Florida State Legislature to Repeal Firearm Preemption Law". U.S. Congressman Alcee L. Hastings. U. S. Federal Government. February 27, 2018. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- ^ "Rep. Alcee Hastings diagnosed with pancreatic cancer". The Washington Post. January 14, 2019. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- ^ Man, Anthony (April 6, 2021). "Congressman Alcee Hastings, after career of triumph, calamity and comeback, dies at 84". Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ "Alcee Hastings campaign account shutting down — after giving his widow its last $23K". Florida Politics. July 18, 2022.

Sources

[edit]- Books

- U.S. House of Representatives (2005). Congressional Directory 2005–2006: One Hundred Ninth Congress. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-16-072467-1.

External links

[edit]- U.S. House website (archived)

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Obituary in Washington Post, April 2021

- Biography at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Financial information (federal office) at the Federal Election Commission

- Legislation sponsored at the Library of Congress

- Profile at Vote Smart

- Alcee Lamar Hastings at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- In Black America; The Honorable Alcee Lamar Hastings, 1986-09-30, KUT Radio, American Archive of Public Broadcasting

- Alcee Hastings Collection, African American Research Library and Cultural Center, Broward County Library

- Whistleblowers Article on the FBI Crime Lab Misconduct

- 1936 births

- 2021 deaths

- 20th-century American judges

- 20th-century American lawyers

- 21st-century African-American people

- African-American Methodists

- African-American judges

- African-American members of the United States House of Representatives

- African-American people in Florida politics

- Deaths from pancreatic cancer

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Florida

- Fisk University alumni

- Florida state court judges

- Howard University alumni

- Impeached United States federal judges removed from office

- Judges of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida

- Methodists from Florida

- People from Altamonte Springs, Florida

- People from Miramar, Florida

- United States district court judges appointed by Jimmy Carter

- 20th-century African-American lawyers

- 21st-century members of the United States House of Representatives

- 20th-century members of the United States House of Representatives