Alamosaurus

| Alamosaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian),

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Restored skeletons of Alamosaurus and Tyrannosaurus at Perot Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Clade: | †Macronaria |

| Clade: | †Titanosauria |

| Family: | †Saltasauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Opisthocoelicaudiinae |

| Genus: | †Alamosaurus Gilmore, 1922 |

| Type species | |

| †Alamosaurus sanjuanensis Gilmore, 1922

| |

Alamosaurus (/ˌæləmoʊˈsɔːrəs/;[1] meaning "Ojo Alamo lizard") is a genus of titanosaurian sauropod dinosaurs containing a single known species, Alamosaurus sanjuanensis, from the Maastrichtian age of the Late Cretaceous period in what is now southwestern North America. It is the only known titanosaur to have inhabited North America after the nearly 30-million year absence of sauropods from the North American fossil record and probably represents an immigrant from South America.

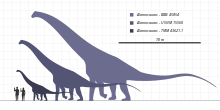

Adults would have measured around 26 metres (85 ft) long, 5 metres (16 ft) tall at the shoulder and weighed up to 30–35 tonnes (33–39 short tons), though some specimens indicate a larger body size. Isolated vertebrae and limb bones suggest that it could have reached sizes comparable to Argentinosaurus and Puertasaurus, which would make it the absolute largest dinosaur known from North America.[2] Its fossils have been recovered from a variety of rock formations spanning the Maastrichtian age. Specimens of a juvenile Alamosaurus sanjuanensis have been recovered from only a few meters below the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary in Texas, making it among the last surviving non-avian dinosaur species.[3]

Description

[edit]

Alamosaurus was a gigantic quadrupedal herbivore with the long neck, the long tail, the relatively long limbs and the body partly covered with bony armor.[3][4] It would have measured around 26 metres (85 ft) long, 5 metres (16 ft) tall at the shoulder and weighed up to 30–35 tonnes (33–39 short tons) based on known adult specimens including TMM 41541-1.[5][3][6][7]

Some scientists suggest larger size estimates for the largest adults. Thomas Holtz proposed a maximum length of around 30 meters (98 ft) or more and an approximate weight of 72.5–80 tonnes (80–88 short tons) or more.[8][9] Though most of the complete remains come from juvenile or small adult specimens, three fragmentary specimens (SMP VP−1625, SMP VP−1850, and SMP VP−2104) suggest that adult Alamosaurus could have grown to enormous sizes comparable to the largest known dinosaurs, like Argentinosaurus, which has been estimated to weigh 73 metric tons (80 short tons).[2] Scott Hartman estimates Alamosaurus, based on a huge incomplete tibia that probably refers to it, being slightly shorter at 28–30 m (92–98 ft) and equal in weight to other massive titanosaurs, such as Argentinosaurus and Puertasaurus,[10] though he states that scientists do not know whether the massive tibia belongs to an Alamosaurus or a completely new species of sauropod.[11]

Though no skull has ever been found, rod-shaped teeth have been found with Alamosaurus skeletons and probably belonged to this dinosaur.[3][12] The vertebrae from the middle part of its tail had elongated centra.[13] Alamosaurus had vertebral lateral fossae that resembled shallow depressions.[13] Fossae that similarly resemble shallow depressions are known from Saltasaurus, Malawisaurus, Aeolosaurus, and Gondwanatitan.[13] Venenosaurus also had depression-like fossae, but its "depressions" penetrated deeper into the vertebrae, were divided into two chambers, and extend farther into the vertebral columns.[13] Alamosaurus had more robust radii than Venenosaurus.[13]

History of discovery

[edit]

Alamosaurus remains have been discovered throughout the southwestern United States. The holotype was discovered in June 1921 by Charles Whitney Gilmore, John Bernard Reeside,[14] and Charles Hazelius Sternberg at the Barrel Springs Arroyo in the Naashoibito Member of the Ojo Alamo Formation (or Kirtland Formation under a different definition) of New Mexico. This formation was deposited during the Maastrichtian age of the Late Cretaceous period.[15] Bones have also been recovered from other Maastrichtian formations, like the North Horn Formation of Utah, the Black Peaks and the Javelina Formations of Texas.[12] Undescribed titanosaur fossils closely associated with Alamosaurus have been found in the Evanston Formation in Wyoming. Three articulated caudal vertebrae were collected above Hams Fork and are housed at the Museum of Paleontology, University of California, Berkeley. However, these specimens have not been described.[16]

Smithsonian paleontologist Gilmore originally described holotype USNM 10486, a left scapula (shoulder bone), and the paratype USNM 10487, a right ischium (pelvic bone) in 1922, naming the type species Alamosaurus sanjuanensis. Contrary to popular assertions, the dinosaur is not named after the Alamo in San Antonio, Texas, or the battle that was fought there.[17] The holotype, the specimen the name was based on, was discovered in New Mexico and, at the time of its naming, Alamosaurus had not yet been found in Texas. Instead, the name Alamosaurus comes from Ojo Alamo, the geologic formation in which it was found and which was, in turn, named after the nearby Ojo Alamo trading post. Since this time, there has been some debate as to whether to reclassify the Alamosaurus-bearing rocks as belonging to the Kirtland Formation or if they should remain in the Ojo Alamo Formation. The term alamo itself is a Spanish word meaning "poplar" and is used for the local subspecies of cottonwood tree. The term saurus is derived from saura (σαυρα), the Greek word for "lizard", and is the most common suffix used in dinosaur names. There is only one species in the genus, Alamosaurus sanjuanensis, which is named after San Juan County, New Mexico, where the first remains were found.[15]

In 1946, Gilmore posthumously described a more complete specimen, USNM 15660, found on June 15, 1937, on the North Horn Mountain of Utah by George B. Pearce. It consists of a complete tail, a complete right forelimb (except for the fingers, which later research showed do not ossify with Titanosauridae), and both ischia.[18] Since then, hundreds of other bits and pieces from Texas, New Mexico, and Utah have been referred to Alamosaurus, often without much description. Despite being fragmentary, until the second half of the twentieth century they, represented much of the globally known titanosaurid material. The most completely known specimen, TMM 43621–1, is a juvenile skeleton from Texas which allowed educated estimates of length and mass.[3]

Some blocks catalogued under the same accession number as the relatively complete and well-known Alamosaurus specimen USNM 15660 and found in very close proximity to it based on bone impressions were first investigated by Michael Brett-Surman in 2009. In 2015, he reported that the blocks contained osteoderms, the first confirmation of their existence on Alamosaurus.[4]

The restored Alamosaurus skeletal mount at the Perot Museum (pictured right) was discovered when student Dana Biasatti, a member of an excavation team at a nearby site, went on a hike to search for more dinosaur bones in the area.[5]

Depositional age

[edit]Alamosaurus fossils are most notably found in the Naashoibito member of the Ojo Alamo Formation (dated to between about 69–68 million years old) and in the Javelina Formation, though the exact age range of the latter has been difficult to determine.[19] A juvenile specimen of Alamosaurus has been reported to come from the Black Peaks Formation, which overlies the Javelina in Big Bend, Texas, and also straddles the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary. The Alamosaurus specimen was reported to come from a few meters below the boundary, dated to 66 million years ago, though the position of the boundary in this region is uncertain.[3]

Only one geological site in the Javelina Formation has yielded the correct rock types for radiometric dating so far. The outcrop, situated in the middle strata of the formation about 90 meters (300 ft) below the K-Pg boundary and within the local range of Alamosaurus fossils, was dated to 69.0±0.9 million years old in 2010.[20] Using this date, in correlation with a measured age from the underlying Aguja Formation and the likely location of the K-Pg boundary in the overlying Black Peaks Formation, the Alamosaurus fauna seems to have lasted from about 70–66 million years ago, with the earliest records of Alamosaurus near the base of the Javelina Formation and the latest just below the K-Pg boundary in the Black Peaks Formation.[20]

Classification

[edit]In 1922, Gilmore was uncertain about the precise affinities of Alamosaurus and did not determine it any further than a general Sauropoda.[15] In 1927, Friedrich von Huene placed it in Titanosauridae.[21]

Alamosaurus was, in any case, an advanced and derived member of the group Titanosauria, but its relationships within that group are far from certain. The issue is further complicated by some researchers rejecting the name Titanosauridae and replacing it with Saltasauridae. One major analysis unites Alamosaurus with Opisthocoelicaudia in the subgroup Opisthocoelicaudiinae of Saltasauridae.[22] A major competing analysis finds Alamosaurus as a sister taxon to Pellegrinisaurus, with both genera located just outside Saltasauridae.[23] Studies finding a close relationship between Alamosaurus and Opisthocoelicaudia did not include Pellegrinisaurus in their analyses.[24] Other scientists have also noted particular similarities with the saltasaurid Neuquensaurus and the Brazilian Trigonosaurus (the "Peiropolis titanosaur"), which is used in many cladistic and morphologic analyses of titanosaurians.[3] A recent analysis published in 2016 by Anthony Fiorillo and Ron Tykoski indicates that Alamosaurus was a sister taxon to Lognkosauria and therefore to species such as Futalognkosaurus and Mendozasaurus, laying outside Saltasauridae (possibly being descended from close relations to the Saltasauridae), based on synapomorphies of cervical vertebral morphologies and two cladistic analyses.[5] The same study also suggests that the ancestors of Alamosaurus hailed from South America instead of Asia.[25] The position of Alamosaurus recovered by phylogenetic analyses varies. Alamosaurus has been recovered as an opisthocoelicaudiine,[22] saltasaurine,[26] or outside of Saltasauridae entirely.[5][24][27][28]

Phylogeny

[edit]Alamosaurus in a cladogram after Navarro et al., 2022:[26]

| Saltasauridae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleogeography

[edit]

Alamosaurus is the only known sauropod to have lived in North America after the sauropod hiatus, a nearly 30-million-year interval for which no definite sauropod fossils are known from the continent. The earliest fossils of Alamosaurus date to the Maastrichtian age, around 70 million years ago, and it rapidly became the dominant large herbivore of southern Laramidia.[29]

The origins of Alamosaurus are highly controversial, with three hypotheses that have been proposed. The first of these, which has been termed the "austral immigrant" scenario,[30] proposes that Alamosaurus is descended from South American titanosaurs. Alamosaurus is closely related to South American titanosaurs, such as Pellegrinisaurus.[24][31] Alamosaurus appears in North America at the same time that hadrosaurs closely related to North American species first appear in South America, suggesting that the Alamosaurus lineage crossed into North America on the same routes as hadrosaurs crossed into South America.[32] The austral immigrant hypothesis has been challenged on the grounds that the routes connecting North and South America during the Maastrichtian may have consisted of separate islands, which would have presented challenges to the dispersal of titanosaurs.[29][33]

A second scenario, termed the "inland herbivore" scenario,[30] suggests that titanosaurs were present in North America throughout the Late Cretaceous and that their apparent absence reflects the relative rarity of fossil sites preserving the upland environments that titanosaurs favored, rather than their true absence from the continent.[29] However, there is no evidence for sauropods in North America between the mid-Cenomanian and the early Maastrichtian, even in strata that preserve more upland environments, and the sauropods that lived in North America before the hiatus are basal titanosauriforms, such as Sonorasaurus and Sauroposeidon, not lithostrotian titanosaurs.[32][34] A third option is that, as in the austral immigrant scenario, Alamosaurus is not native to North America, but originated in Asia instead of South America.[33] Alamosaurus is commonly considered to be closely related to the Asian titanosaur Opisthocoelicaudia, but this is based on analyses that did not take Alamosaurus's South American relative Pellegrinisaurus into account.[24] Though many dinosaurs crossed between Asia and North America across the Bering land bridge, sauropods were poorly adapted for high-latitude environments and Beringia would have been an inhospitable environment for titanosaurs.[35] Furthermore, in order to reach southern Laramidia from Asia, Alamosaurus would have had to cross through Northern Laramidia, which contains no known sauropod fossils of comparable age to Alamosaurus, despite containing the best-studied dinosaur faunas on the continent.[5] Overall, a South American origin has been favored by several studies[31][5][24][35] and Chiarenza et al. (2022) regarded it as "the only viable origin" for Alamosaurus.[35]

Paleoenvironment

[edit]

Skeletal elements of Alamosaurus are among the most common Late Cretaceous dinosaur fossils found in the United States Southwest and are now used to define the fauna of that time and place, known as the "Alamosaurus fauna". In the south of Late Cretaceous North America, the transition from the Edmontonian to the Lancian faunal stages is even more dramatic than it was in the north. Thomas M. Lehman describes it as "the abrupt reemergence of a fauna with a superficially 'Jurassic' aspect. These faunas are dominated by Alamosaurus and feature abundant Quetzalcoatlus in Texas. The Alamosaurus-Quetzalcoatlus association probably represent semi-arid inland plains.[29]

Specimens of Alamosaurus sanjuanensis are known from four geological formations of the American southwest: Ojo Alamo Formation, North Horn Formation, Javelina Formation and Black Peaks Formation.[3] Excluding the Black Peaks Formation, remains of troodontids and hadrosaurids have been discovered from the other three formations.[36][37][38] Contemporary reptiles from the North Horn Formation which are diagnostic to the species level include the tyrannosaurid Tyrannosaurus rex,[39] the chasmosaurine ceratopsid Torosaurus utahensis,[40] the possible crocodylomoprh Pinacosuchus mantiensis,[36] and the lizards Polyglyphanodon sternbergi, Paraglyphanodon utahensis and Paraglyphanodon gazini.[41][36] Specimens possibly belonging to or similar to Tyrannosaurus rex and Torosaurus utahensis (identified as cf. Tyrannosaurus and Torosaurus cf. utahensis) have been discovered from the Javelina Formation,[42][43] where other archosaurs diagnostic to the species level have been discovered including the chasmosaurine ceratopsid Bravoceratops polyphemus,[44] and the large azhdarchid pterosaurs Quetzalcoatlus northropi, Quetzalcoatlus lawsoni and Wellnhopterus brevirostris.[45] Contemporary archosaurs in the Ojo Alamo Formation include the potentially dubious oviraptorosaur Ojoraptorsaurus,[46] the dromaeosaurid Dineobellator,[47] the armored nodosaurid Glyptodontopelta,[48] and the chasmosaurine ceratopsid Ojoceratops.[49] Non-archosaurian taxa that shared the same environment with Alamosaurus include various species of fish, rays, amphibians, lizards, turtles and multituberculates.[50][51][52] A possible specimen of the genus identified as Alamosaurus sp. or cf. Alamosaurus coexisted with dinosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus mcraeensis and Sierraceratops from the McRae Group.[42][53]

References

[edit]- ^ "Alamosaurus". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021.

- ^ a b Fowler, D. W.; Sullivan, R. M. (2011). "The First Giant Titanosaurian Sauropod from the Upper Cretaceous of North America". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 56 (4): 685. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.694.3759. doi:10.4202/app.2010.0105. S2CID 53126360.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lehman, T.M.; Coulson, A.B. (2002). "A juvenile specimen of the sauropod Alamosaurus sanjuanensis from the Upper Cretaceous of Big Bend National Park, Texas" (PDF). Journal of Paleontology. 76 (1): 156–172. doi:10.1017/s0022336000017431. S2CID 232345559.

- ^ a b Carrano, M.T.; D'Emic, M.D. (2015). "Osteoderms of the titanosaur sauropod dinosaur Alamosaurus sanjuanensis Gilmore, 1922". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 35 (1): e901334. Bibcode:2015JVPal..35E1334C. doi:10.1080/02724634.2014.901334. S2CID 86797277.

- ^ a b c d e f Tykoski, Ronald S.; Fiorillo, Anthony R. (2017). "An articulated cervical series of Alamosaurus sanjuanensis Gilmore, 1922 (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from Texas: new perspective on the relationships of North America's last giant sauropod". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 15 (5): 1–26. Bibcode:2017JSPal..15..339T. doi:10.1080/14772019.2016.1183150.

- ^ Benson, Roger B. J.; Campione, Nicolás E.; Carrano, Matthew T.; Mannion, Philip D.; Sullivan, Corwin; Upchurch, Paul; Evans, David C. (May 6, 2014). "Rates of Dinosaur Body Mass Evolution Indicate 170 Million Years of Sustained Ecological Innovation on the Avian Stem Lineage". PLOS Biology. 12 (5): e1001853. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001853. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 4011683. PMID 24802911. Supplementary Information

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (2019). "Determining the largest known land animal: A critical comparison of differing methods for restoring the volume and mass of extinct animals" (PDF). Annals of the Carnegie Museum. 85 (4): 335–358. doi:10.2992/007.085.0403. S2CID 210840060.

- ^ Holtz Jr., Thomas R. (2007). Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. Random House Children's Books. ISBN 978-0-375-82419-7. "Winter 2011 Apendix" (PDF).

- ^ Holtz Jr., Thomas R. (2014). "Supplementary Information to Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages".

- ^ "Assessing Alamosaurus". Skeletal Drawing.

- ^ "The biggest of the big". Skeletal Drawing.

- ^ a b Weishampel, D.B. et al.. (2004). "Dinosaur Distribution (Late Cretaceous, North America)". In Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., Oslmolska, H. (eds.). "The Dinosauria (Second ed.)". University of California Press.

- ^ a b c d e Tidwell, V., Carpenter, K. & Meyer, S. 2001. New Titanosauriform (Sauropoda) from the Poison Strip Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation (Lower Cretaceous), Utah. In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. D. H. Tanke & K. Carpenter (eds.). Indiana University Press, Eds. D.H. Tanke & K. Carpenter. Indiana University Press. 139–165.

- ^ [1], John Bernard Reeside (1889-1958) was a geologist specializing in the study of the Mesozoic stratigraphy and paleontology of the western United States. While receiving his education at The Johns Hopkins University (A.B., 1911; Ph.D., 1915), he joined the United States Geological Survey (USGS) as a part-time assistant... [and] remained with the USGS for his entire professional career... From 1932 to 1949, Reeside was Chief of the Paleontology and Stratigraphy Branch.

- ^ a b c Gilmore, C.W. (1922). "A new sauropod dinosaur from the Ojo Alamo Formation of New Mexico" (PDF). Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. 72 (14): 1–9.

- ^ Lucas and Hunt, Spencer G. and Adrian P. (1989). Farlow, James O. (ed.). "Alamosaurus and the Sauropod Hiatus in the Cretaceous of the North American Western Interior". Paleobiology of the Dinosaurs. Geological Society of America Special Papers. 238 (238): 75–86. doi:10.1130/SPE238-p75. ISBN 0-8137-2238-1.

- ^ Anthony D. Fredericks, 2012, Desert Dinosaurs: Discovering Prehistoric Sites in the American Southwest, The Countryman Press, p. 102-103

- ^ Gilmore, C.W. 1946. Reptilian fauna of the North Horn Formation of central Utah. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper. 210-C:29–51.

- ^ Sullivan, R.M., and Lucas, S.G. 2006. "The Kirtlandian land-vertebrate "age" – faunal composition, temporal position and biostratigraphic correlation in the nonmarine Upper Cretaceous of western North America[permanent dead link]." New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Bulletin 35:7–29.

- ^ a b Lehman, T. M.; Mcdowell, F. W.; Connelly, J. N. (2006). "First isotopic (U-Pb) age for the Late Cretaceous Alamosaurus vertebrate fauna of West Texas, and its significance as a link between two faunal provinces". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (4): 922–928. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[922:fiuaft]2.0.co;2. S2CID 130280606.

- ^ v. Huene, F. (1927). "Sichtung der Grundlagen der jetzigen Kenntnis der Sauropoden". Eclogae Geologicae Helveticae. 20: 444–470.

- ^ a b Wilson, J.A. (2002). "Sauropod dinosaur phylogeny: critique and cladistic analysis" (PDF). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 136 (2): 217–276. doi:10.1046/j.1096-3642.2002.00029.x.

- ^ Upchurch, P., Barrett, P.M. & Dodson, P. 2004. Sauropoda. In: Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., & Osmolska, H. (Eds.) The Dinosauria (2nd Edition). Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 259–322.

- ^ a b c d e Cerda, Ignacio; Zurriaguz, Virginia Laura; Carballido, José Luis; González, Romina; Salgado, Leonardo (July 21, 2021). "Osteology, paleohistology and phylogenetic relationships of Pellegrinisaurus powelli (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentinean Patagonia". Cretaceous Research. 128: 104957. Bibcode:2021CrRes.12804957C. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104957. ISSN 0195-6671.

- ^ "Blogs". PLOS. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ a b Navarro, Bruno A.; Ghilardi, Aline M.; Aureliano, Tito; Díaz, Verónica Díez; Bandeira, Kamila L. N.; Cattaruzzi, André G. S.; Iori, Fabiano V.; Martine, Ariel M.; Carvalho, Alberto B.; Anelli, Luiz E.; Fernandes, Marcelo A.; Zaher, Hussam (September 15, 2022). "A new nanoid titanosaur (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Brazil". Ameghiniana. 59 (5): 317–354. doi:10.5710/AMGH.25.08.2022.3477. ISSN 1851-8044. S2CID 251875979.

- ^ Gorscak, Eric; Lamanna, Matthew C.; Schwarz, Daniela; Díez Díaz, Verónica; Salem, Belal S.; Sallam, Hesham M.; Wiechmann, Marc Filip (July 20, 2023). "A new titanosaurian (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian) Quseir Formation of the Kharga Oasis, Egypt". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 42 (6): –2199810. doi:10.1080/02724634.2023.2199810. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ Filippi, Leonardo S.; Juárez Valieri, Rubén D.; Gallina, Pablo A.; Méndez, Ariel H.; Gianechini, Federico A.; Garrido, Alberto C. (October 30, 2023). "A rebbachisaurid-mimicking titanosaur and evidence of a Late Cretaceous faunal disturbance event in South-West Gondwana". Cretaceous Research. 154: 105754. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2023.105754. ISSN 0195-6671.

- ^ a b c d Lehman, Thomas M. (2001). "Late Cretaceous dinosaur provinciality". In Tanke, Darren H.; Carpenter, Kenneth (eds.). Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Life of the past. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 310–328. ISBN 0-253-33907-3.

- ^ a b <Lucas, Spencer G.; Hunt, Adrian P. (January 1, 1989). "Alamosaurus and the sauropod hiatus in the Cretaceous of the North American Western Interior". Paleobiology of the Dinosaurs. Geological Society of America Special Papers. 238: 75–86. doi:10.1130/SPE238-p75. ISBN 0-8137-2238-1.

- ^ a b Gorscak, Eric; O‘Connor, Patrick M. (April 30, 2016). "Time-calibrated models support congruency between Cretaceous continental rifting and titanosaurian evolutionary history". Biology Letters. 12 (4): 20151047. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2015.1047. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 4881341. PMID 27048465.

- ^ a b D'Emic, Michael D.; Wilson, Jeffrey A.; Thompson, Richard (2010). "The end of the sauropod dinosaur hiatus in North America". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 297 (2): 486–490. Bibcode:2010PPP...297..486D. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.08.032. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ a b Mannion, Philip D.; Upchurch, Paul (January 15, 2011). "A re-evaluation of the 'mid-Cretaceous sauropod hiatus' and the impact of uneven sampling of the fossil record on patterns of regional dinosaur extinction". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 299 (3): 529–540. Bibcode:2011PPP...299..529M. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.12.003. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ D’Emic, Michael D.; Foreman, Brady Z. (July 2012). "The beginning of the sauropod dinosaur hiatus in North America: insights from the Lower Cretaceous Cloverly Formation of Wyoming". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (4): 883–902. Bibcode:2012JVPal..32..883D. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.671204. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 128486488.

- ^ a b c Chiarenza, Alfio Alessandro; Mannion, Philip D.; Farnsworth, Alex; Carrano, Matthew T.; Varela, Sara (December 17, 2021). "Climatic constraints on the biogeographic history of Mesozoic dinosaurs". Current Biology. 32 (3): 570–585.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.11.061. hdl:11093/5013. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 34921764. S2CID 245273901.

- ^ a b c Cifelli, Richard L.; Nydam, Randall L.; Eaton, Jeffrey G.; Gardner, James D.; Kirkland, James I. (1999). "Vertebrate faunas of the North Horn Formation (Upper Cretaceous–Lower Paleocene), Emery and Sanpete Counties, Utah". In Gillette, David D. (ed.). Vertebrate Paleontology in Utah. Salt Lake City: Utah Geological Survey. pp. 377–388. ISBN 1-55791-634-9.

- ^ Tweet, J.S.; Santucci, V.L. (2018). "An Inventory of Non-Avian Dinosaurs from National Park Service Areas" (PDF). New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 79: 703–730.

- ^ Sullivan, Robert M.; Lucas, Spencer G. (2015). "Cretaceous Vertebrates of New Mexico". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 68.

- ^ Sampson, Scott D.; Loewon, Mark A. (June 27, 2005). "Tyrannosaurus rex from the Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) North Horn Formation of Utah: Biogeographic and Paleoecologic Implications". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (2): 469–472. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0469:TRFTUC]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 4524461. S2CID 131583311.

- ^ Sullivan, R.M.; Boere, A.C.; Lucas, S.G. (2005). "Redescription of the ceratopsid dinosaur Torosaurus utahensis (Gilmore, 1946) and a revision of the genus". Journal of Paleontology. 79 (3): 564–582. Bibcode:2005JPal...79..564S. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2005)079<0564:ROTCDT>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Gilmore, Charles W. (1946). Reptilian fauna of the North Horn Formation of central Utah (Vol. 210). Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office. pp. 29–53. doi:10.3133/PP210C. S2CID 128849169.

- ^ a b Dalman, Sebastian G.; Loewen, Mark A.; Pyron, R. Alexander; Jasinski, Steven E.; Malinzak, D. Edward; Lucas, Spencer G.; Fiorillo, Anthony R.; Currie, Philip J.; Longrich, Nicholas R. (January 11, 2024). "A giant tyrannosaur from the Campanian–Maastrichtian of southern North America and the evolution of tyrannosaurid gigantism". Scientific Reports. 13 (1): 22124. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-47011-0. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 10784284. PMID 38212342.

- ^ Hunt, ReBecca K.; Lehman, Thomas M. (2008). "Attributes of the ceratopsian dinosaur Torosaurus, and new material from the Javelina Formation (Maastrichtian) of Texas". Journal of Paleontology. 82 (6): 1127–1138. Bibcode:2008JPal...82.1127H. doi:10.1666/06-107.1. S2CID 129385183.

- ^ Wick, Steven L.; Lehman, Thomas M. (July 1, 2013). "A new ceratopsian dinosaur from the Javelina Formation (Maastrichtian) of West Texas and implications for chasmosaurine phylogeny". Naturwissenschaften. 100 (7): 667–682. Bibcode:2013NW....100..667W. doi:10.1007/s00114-013-1063-0. PMID 23728202. S2CID 16048008. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- ^ Andres, B.; Langston, W. Jr. (2021). "Morphology and taxonomy of Quetzalcoatlus Lawson 1975 (Pterodactyloidea: Azhdarchoidea)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 41 (sup1): 142. Bibcode:2021JVPal..41S..46A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2021.1907587. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 245125409.

- ^ Funston, G. F.; Williamson, T. E.; Brusatte, S. L. (2024). "A caenagnathid tibia (Theropoda: Oviraptorosauria) from the upper Campanian Kirtland Formation of New Mexico". Cretaceous Research. 158 (in press). 105856. Bibcode:2024CrRes.15805856F. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2024.105856.

- ^ Jasinski, Steven E.; Sullivan, Robert M.; Dodson, Peter (March 26, 2020). "New Dromaeosaurid Dinosaur (Theropoda, Dromaeosauridae) from New Mexico and Biodiversity of Dromaeosaurids at the end of the Cretaceous". Scientific Reports. 10 (5105): 5105. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.5105J. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-61480-7. PMC 7099077. PMID 32218481.

- ^ T.L. Ford. (2000). "A review of ankylosaur osteoderms from New Mexico and a preliminary review of ankylosaur armor", In: S. G. Lucas and A. B. Heckert (eds.), Dinosaurs of New Mexico. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 17: 157-176

- ^ Robert M. Sullivan and Spencer G. Lucas, 2010, "A New Chasmosaurine (Ceratopsidae, Dinosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous Ojo Alamo Formation (Naashoibito Member), San Juan Basin, New Mexico", In: Ryan, M.J., Chinnery-Allgeier, B.J., and Eberth, D.A. (eds.) New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: The Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 656 pp.

- ^ Gilmore, Charles W. (1946). Reptilian fauna of the North Horn Formation of central Utah (Vol. 210). Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office. pp. 29–53. doi:10.3133/PP210C. S2CID 128849169.

- ^ Hunt, ReBecca K.; Santucci, Vincent L.; Kenworthy, Jason (2006). "A preliminary inventory of fossil fish from National Park Service units." in S.G. Lucas, J.A. Spielmann, P.M. Hester, J.P. Kenworthy, and V.L. Santucci (ed.s), Fossils from Federal Lands". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 34: 63–69.

- ^ Willamson, Thomas M.; Weil, Anne (September 12, 2008). "Metatherian Mammals from the Naashoibito Member, Kirtland Formation, San Juan Basin, New Mexico and Their Biochronologic and Paleobiogeographic Significance". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (3). Taylor & Francis, Ltd.: 803–815. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[803:MMFTNM]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 20491004. S2CID 140555450. Retrieved November 19, 2020.

- ^ Lozinsky, Richard P.; Hunt, Adrian P.; Wolberg, Donald L.; Lucas, Spencer G. (1984). "Late Cretaceous (Lancian) dinosaurs from the McRae Formation, Sierra County, New Mexico" (PDF). New Mexico Geology. 6 (4): 72–77. doi:10.58799/NMG-v6n4.72. ISSN 0196-948X. S2CID 237011797.

Notes

[edit]- Late Cretaceous dinosaurs of North America

- Saltasaurids

- Natural history of San Juan County, New Mexico

- Fossil taxa described in 1922

- Taxa named by Charles W. Gilmore

- Paleontology in New Mexico

- Paleontology in Utah

- Paleontology in Texas

- Ojo Alamo Formation

- Maastrichtian genera

- Sauropods of North America

- Monotypic sauropod genera