Alabama's congressional districts

The U.S. state of Alabama is currently divided into seven congressional districts, each represented by a member of the United States House of Representatives.

Since the 1973 redistricting following the 1970 U.S. census, Alabama has had seven congressional districts. This is three fewer districts than the historic high of ten congressional districts just prior to the 1930 census.

In the case of Allen v. Milligan, 599 U.S. 1 (2023), the Supreme Court of the United States held that the state's current map violates section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (52 U.S.C. § 10301) and needs to be redrawn with an additional black-majority district. The Alabama Legislature approved another map which also violated the law, but a federal court selected a new map on appeal.[1]

Current districts and representatives

[edit]The delegation has seven members: 5 Republicans and 2 Democrats.

| Current U.S. representatives from Alabama | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| District | Member (Residence)[2] |

Party | Incumbent since | CPVI (2022)[3] |

District map |

| 1st |  Barry Moore (Enterprise) |

Republican | January 3, 2025 | R+28 |  |

| 2nd |  Shomari Figures (Mobile) |

Democratic | January 3, 2025 | D+4 |  |

| 3rd |  Mike Rogers (Weaver) |

Republican | January 3, 2003 | R+23 |  |

| 4th |  Robert Aderholt (Haleyville) |

Republican | January 3, 1997 | R+33 |  |

| 5th |  Dale Strong (Huntsville) |

Republican | January 3, 2023 | R+17 |  |

| 6th |  Gary Palmer (Hoover) |

Republican | January 3, 2015 | R+22 |  |

| 7th |  Terri Sewell (Birmingham) |

Democratic | January 3, 2011 | D+12 |  |

Redistricting

[edit]2000s

[edit]The redistricting in 2002 following the 1990 census marginally strengthened the Democratic position, but did not contribute to any net changes by the parties over the decade. The biggest change in 2002 was to the 3rd district, which lost then arch-Republican stronghold St. Clair County in exchange for more Democratic parts of Montgomery County, including the area around the capitol. The district's black composition rose by 7 percent as a result. However, this did not lead to an unseating of the Republican member. The seat flips during the decade were a fluke flip of the Wiregrass-based 2nd district in the Democratic wave of 2008, and a flip (via party switch and then election of a different Republican) of the Huntsville and north Alabama-based 5th district as part of the continuing realignment of the rural white South towards nearly unanimous support for the Republican party.[citation needed]

The Alabama Legislature is in charge of apportionment and redistricting in Alabama. A bipartisan interim committee of 22 representatives (11 from the Alabama House of Representatives, and 11 from the Alabama Senate) is formed to develop a redistricting plan for recommendation to the legislature. The governor has veto power over both the state legislative and congressional plans.

All redistricting plans in recent history have been court-ordered due to a failure on the part of the legislature to enact their own plans. The redistricting plan adopted after the 1990 census was first proposed by Republicans and ordered into effect by the federal courts. That plan moved black residents out of the 2nd and 6th districts, which had been competitive for Democrats.

The 6th and 7th districts are considered by redistricting watch organizations such as Fair Vote and the National Committee for an Effective Congress to be "irregular" or "gerrymandered".[4]

After a federal trial court rejected a racial gerrymandering claim regarding state house districts, the United States Supreme Court vacated and remanded.[5] The five justice majority found "there is strong, perhaps overwhelming, evidence that race did predominate as a factor". Because the trial court had wrongly looked for racial gerrymandering at the statewide level the Supreme Court ordered the trial court to instead look at each district individually.[6]

2020s

[edit]

The initial map after the 2020 census passed by the Republican-controlled legislature in November 2021 did not differ from the previous decade's map. It drew a single district with a heavily black population by putting the most heavily African-American areas of Jefferson and Tuscaloosa counties in with much of the heavily African-American Black Belt and heavily African-American parts of the capital county of Montgomery.[7]

In a per curiam opinion on January 24, 2022,[8] the United States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama blocked as illegal the map passed by the Alabama legislature after a lawsuit was filed by the ACLU and the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, ordering the legislature to draw two districts with either Black voting-age population majorities or "in which Black voters otherwise have an opportunity to elect a representative of their choice."[9] This case reached the Supreme Court soon after. Subsequent briefing followed and oral argument culminated on October 4, 2022.[10] The question presented for deliberations amongst the Justices and an eventual opinion was:

"Whether the state of Alabama's 2021 redistricting plan for its seven seats in the United States House of Representatives violated section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 52 U. S. C. §10301.21"[11]

On June 8, 2023 the United States Supreme Court published its decision in Allen v. Milligan. In a 5-4 opinion by Chief Justice Roberts, joined by Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, Kavanaugh and Jackson, the Court ruled that Alabama's redistricting plan likely violates Section 2 of the VRA of 1965 by diluting the power of black voters, and ordered the State to draw a new map with an additional black-majority district.[12]

The state's legislature proceeded to draw a map which only marginally increased the share of Black voters in the 2nd district. Subsequently, the state was sued by the Milligan plaintiffs for noncompliance with the Court's decision. Soon after, the trial court ruled against the state and appointed a special master to redraw the map,[13] Alabama's Attorney General Steve Marshall appealed to the Supreme Court for a stay of the decision, but his request was denied with no publicized dissents.[14] Following this, the state withdrew all appeals, and one of the three proposed maps was approved by the trial court on October 5, 2023 to be put into place for the remaining decade.[15]

The new map, set to take effect for the 2024 U.S. House elections, significantly alters the 7th and 2nd districts to have slim Black majority or plurality voting-age populations and span across the eastern portion of Alabama's Black Belt, with the 2nd district set to include portions of the cities of Phenix City, Montgomery and Mobile. In addition the map draws the southeastern coastal portion of Alabama from the 2nd district into the 1st district.

History of congressional delegation

[edit]

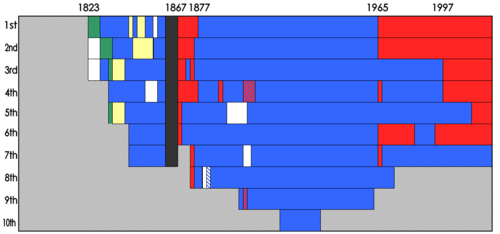

Alabama is typical of most southern states in its pattern, although there are a few interesting deviations. Admitted into the union in 1819, it first appointed members in the 18th United States Congress in 1823. Alabama's growing population coupled with the expansions of the United States House of Representatives meant that by the time the Civil War broke out, Alabama had seven seats - all of which had been dominated by either Democrats or Democratic-Republicans up to that point.

After the civil war, Alabama was subject to the Reconstruction and placed under an effective military control for a period. Typical of this era, freedmen were given the right to vote, and the Republican federal government installed Republican candidates as senators, congressmen and governors. Alabama was no exception. However, by 1874 the Democratic party had re-established itself in Alabama, and a series of redistrictings and then punitive race laws ensured that no Republicans remained congressmen after 1877.

With very little deviation, Southern Democrats (Dixiecrats) remained steadfastly dominant in Alabama until 1965. Over the next 30 years Republicans and Democrats shared representation of Alabama in Congress.

By 1997 the Republicans had come to dominate Alabama's congressional holdings.

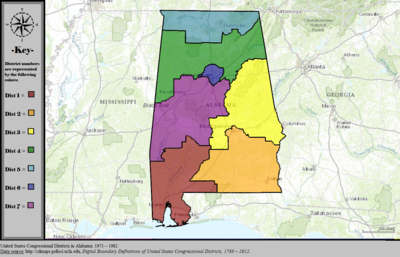

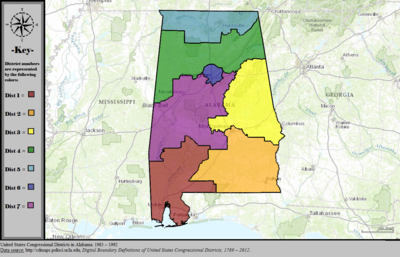

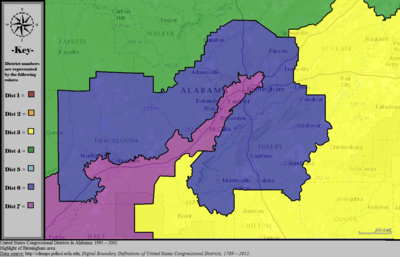

| Year | Statewide map | Birmingham highlight |

|---|---|---|

| 1973–1982 |

|

|

| 1983–1992 |

|

|

| 1993–2002 |

|

|

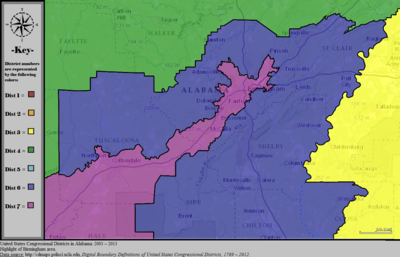

| 2003–2013 |

|

|

| 2013–2023 |

|

|

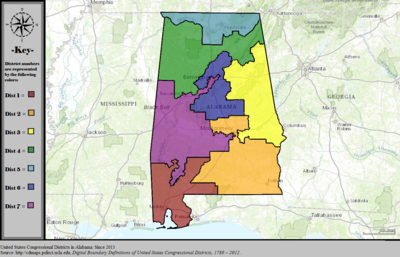

| 2023–2025 |

| |

| From 2025 |

|

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Court picks new Alabama congressional map that will likely flip one seat to Democrats". Politico. October 5, 2023. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

- ^ "Member Profiles". Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ "2022 Cook PVI: District Map and List". Cook Political Report. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ "Alabama Redistricting 2000". FairVote. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ Alabama Legislative Black Caucus v. Alabama, 575 U.S. __(2015).

- ^ "Supreme Court Rejects 'Mechanical Interpretation' of Voting Rights Act | Brennan Center for Justice".

- ^ Lyman, Brian (November 15, 2021). "Alabama redistricting: Take a look at maps for new congressional, legislative districts". Montgomery Advertiser. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- ^ "BOBBY SINGLETON, et al., Plaintiffs, v. JOHN H. MERRILL, in his official capacity as Alabama Secretary of State, et al" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 26, 2022. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- ^ Epstein, Reid (January 24, 2022). "Court Throws Out Alabama's New Congressional Map". New York Times. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- ^ "Docket for 21-1086".

- ^ "21-1086 MERRILL V. MILLIGAN" (PDF). Supreme Court. February 7, 2022. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ "Supreme Court upholds Section 2 of Voting Rights Act". SCOTUSblog. June 8, 2023. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- ^ Vazquez, Maegan (September 5, 2023). "Alabama congressional map struck down again for diluting Black voting power". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ Hurley, Lawrence (September 26, 2023). "Supreme Court rejects Alabama's bid to use congressional map with just one majority-Black district". www.nbcnews.com. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ Cochrane, Emily (October 5, 2023). "Alabama Is Ordered to Use Map With Two Districts That Empower Black Voters". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ^ "Digital Boundary Definitions of United States Congressional Districts, 1789–2012". Retrieved October 18, 2014.