Qadi al-Fadil

Muhyi al-Din (or Mujir al-Din) Abu Ali Abd al-Rahim ibn Ali ibn Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Lakhmi al-Baysani al-Asqalani, better known by the honorific name al-Qadi al-Fadil (Arabic: القاضي الفاضل, romanized: al-Ḳāḍī al-Fāḍil, lit. 'the Excellent Judge';[1] 3 April 1135 – 26 January 1200) was an official who served the last Fatimid caliphs, and became the secretary and chief counsellor of the first Ayyubid sultan, Saladin.

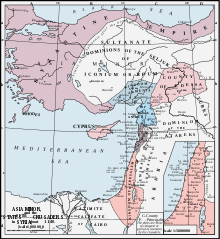

Born in Ascalon to a qadi and financial official, Qadi al-Fadil went to study in Cairo, the Fatimid capital. He entered the Fatimid chancery, and quickly distinguished himself for the elegance of his prose style. In the early 1160s, he was patronized by the viziers Ruzzik ibn Tala'i and Shawar, rising to become head of the fiscal department supervising the army, and receiving the name by which he is known. Despite his prominent position in the Fatimid state, he quickly sided with the fellow Sunni Saladin during the latter's vizierate, and supported him in deposing the Fatimid dynasty, which was achieved in 1171.

In the new Ayyubid regime, Qadi al-Fadil was an important figure, serving as Saladin's chief counsellor. He was left in charge of the Egyptian administration during Saladin's wars in the Levant. As a result, historians often attribute to him the title of vizier, which he never held. After Saladin's death in 1193, Qadi al-Fadil served Saladin's son al-Afdal, ruler of Damascus, before switching his allegiance to Saladin's second son, al-Aziz, ruler of Egypt. He retired after 1195, and died in 1200.

Qadi al-Fadil's reputation among contemporaries and later generations rests chiefly on his skill as an epistolary writer. His style was much admired and widely emulated by later generations. The corpus of his letters is also an important historical source for the period. In addition, he founded a madrasah in Cairo, and donated his large library to the institution.

Life

[edit]Service under the Fatimids

[edit]

Qadi al-Fadil was born on 2 April 1135 at Ascalon.[2] His father, known as al-Qadi al-Ashraf (d. 1149/50), was serving as judge (qadi) and financial comptroller (nazir) there.[3][4] The exact significance of the epithet 'al-Baysani' is unclear: one version holds that the family hailed from Baysan, while another that it hailed from Ascalon, but that Qadi al-Ashraf had previously served as qadi at Baysan.[5]

Qadi al-Fadil received his basic education at his home town,[6] before moving to Cairo in c. 1148/49, where, at the initiative of his father, he entered the chancery (diwan al-insha) of the Fatimid Caliphate as a trainee.[3] The long-serving head of the chancery, Ibn Khallal, became his patron during his subsequent career.[6] This training included administrative practice and especially the arts of epistolary and secretarial writing. Despite his own title of qadi, however, it is unclear whether Qadi al-Fadil also received judicial education at any point. The title was common for officials in the Fatimid administration as a honorific, and under the Isma'ili Shi'a Fatimid regime, there were no Sunni schools in Cairo where he, as a Sunni, might have acquired the necessary training.[7]

According to the 13th-century encyclopaedist Yaqut al-Hamawi, at this time Qadi al-Fadil's father fell into disgrace because he failed to inform Cairo of the release of an important hostage by the governor of Ascalon. His property was confiscated, and he died, destitute, soon after. According to this account, Qadi al-Fadil had to interrupt his apprenticeship and go on foot to Alexandria,[8] where by 1153 he had become secretary to the qadi of Alexandria, Ibn Hadid.[3] His small salary of three gold dinars per month did not suffice to care for his mother, brother and sister back in Ascalon, but following the fall of Ascalon to the Crusaders in the same year, the rest of his family moved to Egypt.[9] Alexandria was the seat of a Maliki law school, but it is again unknown if he attended it. The only available information comes from the later writer al-Mundhiri, who reports that during his stay in Alexandria, Qadi al-Fadil studied under the two eminent jurists Abu Tahir al-Silafi and Ibn Awf.[10] In this post he distinguished himself due to the artful language of his dispatches, and was called to Cairo by the vizier Ruzzik ibn Tala'i (vizierate: 1161–1163) and appointed head of the army bureau (diwan al-jaysh).[2][3][11]

When Ruzzik was deposed by Shawar, Qadi al-Fadil became the secretary to Shawar's son, Kamil.[3] During Shawar's conflicts with Dirgham, he sided with the former, and was even imprisoned for a time along with Kamil in August 1163, when Dirgham seized power. After the final victory of Shawar in May 1164, Qadi al-Fadil was released and given many honours, including the epithet of al-Fadil (lit. 'the Excellent/Virtuous One'), by which he is known.[2][12]

Switch of allegiance and the fall of the Fatimid Caliphate

[edit] |

| Part of a series on |

| Saladin |

|---|

As a partisan of Shawar, Qadi al-Fadil had originally opposed Shirkuh, the Kurdish general who had invaded Egypt on behalf of his Syrian King, Nur al-Din. Qadi al-Fadil's support extended to supporting Shawar's decision to turn to the Crusaders for aid against the Syrian troops.[13] Nevertheless, within a short time, he managed to gain the friendship of Shirkuh and remained in service in the chancery under both him and his nephew and successor, Saladin.[11] The sources give different accounts of the background of these events. Modern historians generally consider the truthfulness of these reports doubtful, as they are at pains to exculpate Qadi al-Fadil for his sudden change of allegiance from the Fatimids to the Ayyubids.[14]

This change is not difficult to understand. Although a high official of the Fatimid state, Qadi al-Fadil was likely a devoted Sunni, as were most of the civilian bureaucracy at the time. His loyalty to the Fatimid dynasty and the Isma'ili sect was therefore dubious at best, and it was not difficult for him to transfer his allegiance to the Sunni Ayyubids.[15] The Fatimid regime itself was already in decline, challenged by over-mighty viziers who had reduced the caliphs to puppets. The official sect of Isma'ilism had lost its appeal and was weakened by disputes and schisms, and the dynasty's legitimacy was increasingly challenged by a Sunni resurgence that was partly sponsored by the Fatimids' own viziers.[16]

In 1167/8, Qadi al-Fadil became the new head of the chancery, replacing his old patron Ibn Khallal. When the latter died on 4 March 1171, he became the secretary to Saladin.[3] From 1170 on, Saladin gradually moved to dismantle the Fatimid regime and replace Isma'ilism with Sunni Islam.[17][18] The 14th-century Egyptian historian al-Maqrizi ascribes to Saladin and Qadi al-Fadil jointly the common cause of deposing the Fatimid dynasty,[19] and Saladin himself is said to have remarked "I took Egypt not by force of arms but by the pen of Qadi al-Fadil".[2][20]

When Saladin deposed the Fatimid regime outright following the death of caliph al-Adid in September 1171, Qadi al-Fadil played a leading role in carrying out the subsequent changes in the military and fiscal administration of Egypt.[3] Qadi al-Fadil's role in the suppression of a supposed pro-Fatimid conspiracy in April 1174 is unclear. The aftermath included the execution of a number of former Fatimid officials, most notably the poet Umara al-Yamani. Qadi al-Fadil's account of the extent of the conspiracy is at odds with the limited reprisals, and the affair was likely a settling of old rivalries within the former Fatimid administrative elites.[21]

Service under Saladin

[edit]Imad al-Din al-Isfahani, a friend and collaborator who entered Saladin's service through Qadi al-Din's intercession,[22] writes of him that he was the "principal driving force behind the affairs of Saladin's regime", but his exact duties are unclear.[23] Although often called Saladin's vizier, Qadi al-Fadil never held that title. He was nevertheless the closest counsellor and chief secretary of the Ayyubid ruler until Saladin's death.[2][3] He accompanied Saladin in his campaigns in Syria,[3] but in the sources, he is chiefly associated with Egypt, where most of his career took place. Thus in 1188/89 Saladin renewed Qadi al-Fadil's brief to supervise all affairs of Egypt, while in 1190/91 he was tasked with equipping a fleet to assist Saladin in his Siege of Acre.[23]

At the same time, during Saladin's absence in the wars against the Crusaders, the government of Egypt was formally left to other members of the Ayyubid clan. Qadi al-Fadil was critical of Saladin's brother, al-Adil. After he left Egypt, Qadi al-Fadil successfully lobbied for al-Adil's replacement by his friend, Saladin's nephew Taqi al-Din.[24] For unknown reasons, Qadi al-Fadil was not present at Saladin's greatest victory at the Battle of Hattin (1187), nor in the subsequent recapture of Jerusalem.[25]

In Christian sources, Qadi al-Fadil is blamed for the anti-dhimmi purge of the early years of Saladin's rule, which saw Christians evicted and banned from holding posts in the public fiscal administration.[26] At the same time, however, Qadi al-Fadl sponsored a number of Jewish physicians, among them the celebrated philosopher Maimonides, whom he defended from charges of apostasy,[27][28] and who dedicated his book On Poisons and Antidotes to his patron.[1]

From his prominent post, Qadi al-Fadil became a wealthy man: he reportedly received an annual salary of 50,000 gold dinars, and became a successful merchant, trading with India and North Africa.[29] Outside the city walls of Cairo, a change of the course of the Nile had exposed large tracts of land that were exceedingly fertile. Qadi al-Fadil bought much of it, and converted these estates into an orchard that supplied the capital with fruit.[30]

Final years and death

[edit]After Saladin's death at Damascus in March 1193, Qadi al-Fadil initially served his oldest son al-Afdal, ruler of Damascus. Due to al-Afdal's erratic leadership, he quickly returned to Egypt, where he entered the service of al-Aziz, Saladin's second son, who had seized power there.[3][25] When the two brothers came into conflict, Qadi al-Fadil managed to mediate a peace between them in 1195.[3] After this he retired, and died on 26 January 1200.[2][3] He was buried in the Qarafa cemetery in Cairo. A mausoleum was erected on top of his grave.[25]

Qadi al-Fadil's surviving family is mostly obscure. From his many sons, only al-Qadi al-Ashraf Ahmad Abu'l-Abbas is notable, who served the Ayyubid rulers of Egypt until his death in 1245/46.[29]

Writings and patronage of learning

[edit]Already during his lifetime, Qadi al-Fadil was highly esteemed, chiefly due to the "exceptional quality of his private and official epistolary style", which was praised, held up as a model, and emulated by subsequent generations of writers.[3] This style was similar to that of Imad al-Din al-Isfahani, and "combines richness (perhaps a little less prolix) and suppleness of form with a realistic treatment of the facts, a lesson too often forgotten by later writers, which makes his correspondence a valuable historical source".[3] Al-Isfahani himself praises his contemporary as the "lord of word and pen", and writes that just as the Sharia invalidated all previous laws, so Qadi al-Fadil's style overrode all previous traditions in epistle literature (insha).[27] As a result, many of his chancery epistles were included in the works of other authors, from chroniclers such as al-Isfahani and Abu Shama to compilers of insha literature, most notably al-Qalqashandi.[3] Others survive as manuscripts to this day, and the work of editing and publishing them is still ongoing.[3][27] However, they still represent only a part of the reportedly 100 volumes of official and private correspondence attributed to him.[27]

As head of the chancery, Qadi al-Fadil also kept an official diary (known as Mutajaddidat or Majarayat). It has not survived, apart from several extracts from it that have been included in later histories, notably al-Maqrizi, and is an invaluable source on Saladin's rule in Egypt.[3][27][31] According to the 13th-century historian Ibn al-Adim, however, this diary was actually kept by a different historian, Abu Ghalib al-Shaybani.[3]

Qadi al-Fadil was also active as a poet. Many of his works are included in his epistles. His collected poems were published in two volumes in Cairo in 1961 and 1969, edited by Ahmad A. Badawi and Ibrahim al-Ibyari.[27][32]

A famous bibliophile, Qadi al-Fadil amassed a large library, much of which he donated to the Fadiliyya, a madrasah for Maliki and Shafi'i jurisprudence that he founded in 1184/85 at Cairo. It included a hall for studying the recitation of the Quran, an orphanage, and Qadi al-Fadil's private residence.[27][33] His son Ahmad served there as a teacher, and a grandson worked there as librarian.[33]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Kraemer 2005, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d e f Şeşen 2001, p. 114.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Brockelmann & Cahen 1978, p. 376.

- ^ Lev 1999, p. 14.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 14–15, 19.

- ^ a b Lev 1999, p. 15.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 14, 20.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Lev 1999, p. 17.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Lev 1999, p. 21.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 18–19, 21.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 17–19, 78.

- ^ Brett 2017, pp. 276–277, 280ff..

- ^ Brett 2017, p. 293.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 84–86.

- ^ Lev 1999, p. 86.

- ^ Lev 1999, p. 92.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 86–94.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b Lev 1999, p. 22.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b c Lev 1999, p. 23.

- ^ Lev 1999, p. 188.

- ^ a b c d e f g Şeşen 2001, p. 115.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 189–190.

- ^ a b Lev 1999, p. 24.

- ^ Lev 1999, p. 114.

- ^ Lev 1999, pp. 25, 43.

- ^ Brockelmann & Cahen 1978, pp. 376–377.

- ^ a b Lev 1999, p. 128.

Sources

[edit]- Brett, Michael (2017). The Fatimid Empire. The Edinburgh History of the Islamic Empires. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-4076-8.

- Brockelmann, C. & Cahen, Cl. (1978). "al-Ḳāḍī al-Fāḍil". In van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Bosworth, C. E. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume IV: Iran–Kha. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 376–377. OCLC 758278456.

- Kraemer, Joel L. (2005). "Maimonides: An Intellectual Portrait". In Seeskin, Kenneth (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Maimonides. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 10–57. ISBN 978-0-521-52578-7.

- Lev, Yaacov (1999). Saladin in Egypt. Leiden, Boston, Köln: Brill. ISBN 90-04-11221-9.

- Şeşen, Ramazan (2001). "Kādî el-Fâzıl". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 24 (Kāânî-i Şîrâzî – Kastamonu) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 114–115. ISBN 978-975-389-451-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Helbig, Adolph H. (1908). Al-Qāḍi al-Fāḍil, der Wezīr Saladin's. Eine Biographie (PhD dissertation) (in German). Leipzig: W. Drugulin.

- Hillenbrand, Carole (2019). "Saladin's 'Spin Doctors': Prothero Lecture". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 29: 65–77. doi:10.1017/S0080440119000033. S2CID 211952166.

- Jackson, D. (1995). "Some Preliminary Refections on the Chancery Correspondence of the Qadi al-Fadil". In Vermeulen, U.; De Smet, D. (eds.). Egypt and Syria in the Fatimid, Ayyubid and Mamluk Eras, Part 1. Louvain: Peeters Publishers. pp. 207–218. ISBN 90-6831-683-4.

- 1135 births

- 1200 deaths

- Officials of the Fatimid Caliphate

- People from Ashkelon

- People from the Ayyubid Sultanate

- Saladin

- 12th-century people from the Fatimid Caliphate

- Sunni Muslims

- 12th-century Arabic-language poets

- Medieval letter writers

- 12th-century Arabic-language writers

- Bibliophiles

- Muslims of the Crusades

- Egypt under the Ayyubid Sultanate