Life of Riley (2014 film)

| Life of Riley | |

|---|---|

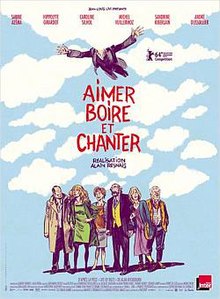

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alain Resnais |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Life of Riley by Alan Ayckbourn |

| Produced by | Jean-Louis Livi |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Dominique Bouilleret |

| Edited by | Hervé de Luze |

| Music by | Mark Snow |

| Distributed by | Le Pacte |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 108 minutes[1] |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Budget | $7.3 million |

| Box office | $4.7 million[2] |

Life of Riley (French: Aimer, boire et chanter) is a 2014 French comedy-drama film directed by Alain Resnais in his final feature film before his death. Adapted from the play Life of Riley by Alan Ayckbourn, the film had its premiere in the competition section of the 64th Berlin International Film Festival,[3] just three weeks before Resnais died, where it won the Alfred Bauer Prize.[4]

Plot

[edit]In Yorkshire, three couples—Kathryn and Colin, Tamara and Jack, Monica and Simeon—are shattered by the news that their mutual friend George Riley is fatally ill and has only a few months left. Thinking how best to help him, they invite him to join their amateur dramatic group, but rehearsals bring their past histories to the surface. When George decides to have a last holiday in Tenerife, each of the women wants to accompany him, and their partners are in consternation.

Cast

[edit]- Sabine Azéma as Kathryn

- Hippolyte Girardot as Colin

- Caroline Silhol as Tamara

- Michel Vuillermoz as Jack

- Sandrine Kiberlain as Monica

- André Dussollier as Simeon

- Alba Gaïa Kraghede Bellugi as Tilly

Production

[edit]Resnais said that he was drawn to Ayckbourn's play Life of Riley by its portrayal of a group of characters who are constantly mistaken about the behaviour and motives of the others and about their own; it questions whether people really match the descriptions which others give of them. Resnais also liked the challenge of Ayckbourn's device of having all the real action take place offstage with characters speaking about things which the audience never sees.[5]

For the third film in succession, Resnais (using his writer's pseudonym of Alex Reval) worked with the writer/director Laurent Herbiet on the screenplay of Aimer, boire et chanter, remaining faithful to the text of Ayckbourn's play (except for some shortening) and preserving its English setting in Yorkshire. He then asked the playwright Jean-Marie Besset, whom he knew for other adaptations of English dramatists, to write the French dialogue with his own rhythms and phrasing.[5]

In choosing four of his cast with whom he had previously worked (Sabine Azéma, André Dussollier, Hippolyte Girardot, and Michel Vuillermoz), Resnais was conscious of assigning them roles in this film which would allow them to give performances distinctly different from what they had done before. Caroline Silhol had worked once for Resnais many years earlier, and Sandrine Kiberlain was the only complete newcomer to his team. Most of his actors also had experience in productions of Ayckbourn's plays.[6]

Resnais wanted to film in a studio in order to preserve a theatrical style of décor which matched Ayckbourn's dialogue, but budget constraints made it impossible to build full sets of the houses of the various couples. He therefore took inspiration from his teenage memory of a stage production of Anton Chekhov's The Seagull for which Georges Pitoëff had used pieces of fabric to give minimal indication of settings. The designer Jacques Saulnier devised a series of painted curtains and simple props to provide a schematic representation of gardens, trees, or facades of houses. The sense of theatricality was reinforced by introducing the scenes with sketches of the setting by the cartoonist and graphic artist Blutch, alongside travelling shots filmed in the roads and lanes of Yorkshire.[6][7][8]

For the title of the film, Resnais chose Aimer, boire et chanter, to convey something of the spirit of the otherwise untranslatable original title. It is also the French title of a waltz by Johann Strauss II, which is heard during several scene transitions; and a vocal version with French words by Lucien Boyer is sung during the final credits in a recording by the tenor Georges Thill.[9]

Reception

[edit]When the film was shown at the Berlin Film Festival in February 2014, it was awarded the Silver Bear Alfred Bauer Prize "for a feature film that opens new perspectives".[10] It also received the Fipresci International Critics Prize for Best Film.[11] (Resnais was too frail to attend the festival in person. He died less than three weeks later.)

Initial critical responses to the film among English-language reviewers were divided between those who appreciated its light-heartedness and fun, rare among festival entries,[8] and those who found it laboured and tedious in the theatricality of its format and the mannered style of performance. The latter view included judgments that "its overtly theatrical style will turn off most viewers beyond the director’s faithful few"[12] and that it was "little more than a lightweight piece of filmed theater" and "largely a superfluous footnote to the lofty career of its nonagenarian director."[13]

Others appreciated the subtlety and wit in its direction: "The intellectual thrust of the film hinges on alienation — from both the text and the staging. This is a wry critique of the theatrical mode whose ample pleasures derive from minute touches which offer a reminder of how the camera, its placement and a delicate edit here or there, can charge a banal text with added emotion and import."[14] And: "Life of Riley isn’t, as far as one can tell from the film, one of Ayckbourn’s most interesting or most formally inventive plays—the key conceit is that Riley himself is never seen but hovers in the background like a convivial Godot. But what’s fascinating is the amount of formal mischief that Resnais whips up. One running joke is the excess of establishing shots, of a singularly artificial variety: every time the scene shifts to one of the characters’ houses, Resnais shows us a cartoon of the place (by French artist Blutch), which then is replaced by a stylized stage-set version of the same locale, designed in dizzyingly distinctive color schemes by Jacques Saulnier, with gorgeously painted curtains standing in for trees, houses, background lawns alike...."[8]

A French critic, writing in English, summarised the director's approach in this late film: "Resnais inserts surrealistic touches such as the appearance of a mole puppet, and creates an uncanny feeling by using British props, newspapers, groceries and maps while the characters all speak French! At once rigorous in its stylistic devices and plot developments and wildly free, the film testifies to an artist who loves to play games, to give free rein to his imagination and, above all, to celebrate life, even in the presence of death."[11]

References

[edit]- ^ "Life of Riley (15)". British Board of Film Classification. 3 February 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ^ "Aimer, boire et chanter (2014)- JPBox-Office". Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "First Films for Competition and Berlinale Special". berlinale. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ "Prizes of the International Jury". berlinale.de. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ a b François Thomas. "Entretien avec Alain Resnais", in Positif, no. 638 (avril 2014), p.15.

- ^ a b François Thomas. "Entretien avec Alain Resnais", in Positif, no. 638 (avril 2014), p.16.

- ^ Jean-Luc Douin. Alain Resnais. Paris: Éditions de la Martinière, 2013. pp.242-243.

- ^ a b c Jonathan Romney, in Film Comment, 13 February 2014. [Retrieved 15 March 2014.]

- ^ François Thomas. "Entretien avec Alain Resnais", in Positif, no. 638 (avril 2014), p.19.

- ^ "- Berlinale - Festival - Awards & Juries - International Jury". Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ a b Michel Ciment. Slices of Cake, at Fipresci. [Retrieved 15 March 2014.]

- ^ Jordan Mintzer, "Life of Riley (Aimer, boire et chanter): Berlin review", in The Hollywood Reporter, 2 February 2014. [Retrieved 15 March 2014].

- ^ Eric Kohn, Berlin review, in Indiewire, 10 February 2014. [Retrieved 16 March 2014.]

- ^ David Jenkins, "Berlin Film Festival 2014: Round-up Part 2", in Little White Lies, 13 February 2014. [Retrieved 15 March 2014.]

External links

[edit]- 2014 films

- 2014 comedy-drama films

- Films scored by Mark Snow

- Films about actors

- Films about theatre

- French films based on plays

- Films directed by Alain Resnais

- Films set in Yorkshire

- Films shot in France

- Films shot in Yorkshire

- French comedy-drama films

- 2010s French-language films

- 2010s French films

- Le Pacte films