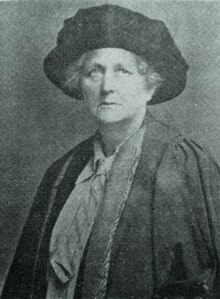

Aleen Cust

Aleen Cust | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Aleen Isobel Cust 7 February 1868 County Tipperary, Ireland |

| Died | 29 January 1937 (aged 68) |

| Occupation | Veterinary surgeon |

| Known for | First woman veterinary surgeon in Great Britain or Ireland |

Aleen Isobel Cust (7 February 1868 – 29 January 1937) was an Anglo-Irish veterinary surgeon. She was born and began her career in Ireland. In 1922 she became the first female veterinary surgeon to be recognised by the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons.[1][2]

Early life and education

[edit]Aleen Cust was born in 1868 in Cordangan Manor, County Tipperary. Her father Sir Leopold Cust, 2nd Baronet was the grandson of Brownlow Cust, 1st Baron Brownlow, and worked as a land agent to the Smith-Barry family.[3] Her mother Charlotte Sobieske Isabel (née Bridgeman) was the daughter of Vice-Admiral Charles Orlando Bridgeman, and granddaughter of Orlando Bridgeman, 1st Earl of Bradford and Sir Henry Chamberlain, 1st Baronet.[1]

The fourth of six children,[4] she enjoyed the outdoors as a child, and when asked about her future she claimed "a vet was my reply ever and always."[5]

She began training as a nurse at London Hospital, but gave it up to become a veterinary surgeon.[1] Following the death of her father in 1878, Major Shallcross Fitzherbert Widdington, her guardian, encouraged her to pursue an education and funded her attendance at William Williams's New Veterinary College in Edinburgh.[6][2] As her mother was acting as a Woman of the Bedchamber to Queen Victoria,[7] Cust enrolled under the name A.I. Custance to avoid any embarrassment for her family.[7] She completed her veterinary studies in 1897, winning the gold medal for zoology,[7] but was denied permission to sit the final examination and consequently was not admitted as a member of Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS).[6] She challenged this in the Court of Session, seeking to overturn the decision of the RCVS examination committee, but the court declined to rule on the basis that the RCVS was not domiciled in Scotland.[7] She refrained from legal action in London, perhaps due to the potential cost, or potential social embarrassment to her mother.[5]

Career

[edit]Cust nevertheless went on to practise in County Roscommon with William Augustine Byrne MRCVS,[3] having received a personal recommendation from William Williams,[6] and lived at Castlestrange House (location of the Castlestrange stone, in the Suck Valley) near Athleague.[4] The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography states that there is reason to believe that Byrne and Cust "lived as man and wife and that she had two daughters, born in Scotland, who were later adopted".[1] In 1904 she was briefly engaged to Bertram Widdington, the son of her former guardian, but following objections from his family regarding her career, the wedding did not go ahead.[8]

Cust was later appointed as a veterinary inspector by Galway County Council under the Diseases of Animals Acts, an appointment that was denied by the RCVS due to her lack of professional recognition.[6] The post was advertised again, and when Cust was again selected for the post an agreement was reached under which she carried out the duties of the position with an amended title.[6] Upon the death of Byrne in 1910, Cust took over the veterinary practice.[4] She practised from Fort Lyster House near Athleague.[9] (Both Castlestrange and Fort Lyster were later demolished.[10])

Upon the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Cust left Ireland to volunteer at the front and appears to have aided in the treatment and care of horses,[6][4] working with the YMCA from a base near Abbeville.[7] In 1917 she was appointed to an army bacteriology laboratory which was associated with a veterinary hospital.[11] She is listed as a member of the Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary Corps from January to November 1918 and it has been suggested that it was her war time work that aided in her acceptance into the RCVS after the war.[11]

The Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons in London did not recognise Cust's right to practice in her own right in Britain until 1922,[12] following the enactment of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919.[13][3][2] Given her years of experience, she was only asked to take the oral part of the final examination.[1] On 21 December 1922, the president of the RCVS, Henry Sumner, personally presented Cust with her diploma, and she thus became the first woman to be awarded such a diploma.[11][14][2]

Later life and recognition

[edit]Due to failing health, Cust only continued to practice as a veterinarian for another two years, retiring in 1924.[6] Having sold her practice, she moved to the village of Plaitford, in the New Forest in Hampshire, England.[4] She died of heart failure[4] in Jamaica on 29 January 1937 whilst visiting friends.[6]

Upon her death she left the RCVS a sum of money to found the Aleen Cust Research Scholarship.[7][2] In 2007 a plaque was erected in honour of Cust at Castlestrange House, Athleague by Women in Technology and Science and the National Committee for Commemorative Plaques in Science and Technology, with support from Veterinary Ireland.[8]

See also

[edit]- Joan Morice - First female South African veterinary surgeon.

- William Ivison Macadam - Encouragement of women

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Hall, Sherwin A. "Cust, Aleen Isabel (1868–1937)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Commire, Anne (1 January 2007). "Cust, Aleen (1868–1937)". Dictionary of Women Worldwide: 25,000 Women Through the Ages. Thomson Gale. ISBN 978-1414418612. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ a b c Ask About Ireland. "Aleen Cust (1868–1937)". Ask About Ireland. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f County Roscommon Archaeological and Historical Society. "Hidden gems and Forgotten People: Aleen Cust (1868–1937)" (PDF). Hidden Gems. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ a b Lewis-Stempel, John (2012). Young James Herriot: The Making of the World's Most Famous Vet. Random House. pp. 159–163. ISBN 978-1-4464-1622-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Vincent, Nicky. "History of Women Veterinarians". Vets Online. Archived from the original on 10 February 2015. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Haines, Catharine M.C. (2001). International Women in Science: A Biographical Dictionary to 1950. Oxford: ABC-CLIO. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-1-57607-090-1.

- ^ a b O'Connell, Claire (2009). "First in Their Field". In Mulvihill, Mary (ed.). Lab Coats and Lace. Dublin: WITS. pp. 37–41. ISBN 978-0-9531953-1-2.

- ^ House: Fort William/Fort Lyster Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Landed Estates Database

- ^ Our cultural revolution: A lament for reason Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine, Roscommon People

- ^ a b c Scott Nolen, R. (18 May 2011). "Britain's first woman veterinarian". American Veterinary Medical Association. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ Nicholson, Virginia (2007). Singled Out. Viking. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-670-91564-4.

- ^ Goodwin, Charlie (1983). 50 Years a Country Veterinarian. Belleville Ontario: Mika Publishing. pp. 21–22.

- ^ "The First Woman Veterinary Surgeon". The British Medical Journal. 2 (3234): 1236–1236. 1922. ISSN 0007-1447.

Further reading

[edit]- Ford, Connie M. (1990). "Aleen Cust, Veterinary Surgeon – Britain's First Woman Vet". Biopress. ISBN 0-948737-11-5

- Ó hÓgartaigh, Margaret (2006). 'Female Veterinary Surgeons in Ireland, 1900-30', Irish Veterinary Journal, 59: pp. 388–389.

- Quinn, Martin (2020) Tipperary People of Great Note, https://www.orpenpress.com/books/tipperary-people-of-great-note/?cgkit_search_word=tipp