Old Kingdom of Egypt

Old Kingdom of Egypt | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 2686 BC–c. 2181 BC | |||||||||

![During the Old Kingdom of Egypt (circa 2700 BC – circa 2200 BC), Egypt consisted of the Nile River region south to Abu (also known as Elephantine), as well as Sinai and the oases in the western desert, with Egyptian control/rule over Nubia reaching to the area south of the third cataract.[1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a2/4th_Dynasty_of_Egypt-03.png/250px-4th_Dynasty_of_Egypt-03.png) During the Old Kingdom of Egypt (circa 2700 BC – circa 2200 BC), Egypt consisted of the Nile River region south to Abu (also known as Elephantine), as well as Sinai and the oases in the western desert, with Egyptian control/rule over Nubia reaching to the area south of the third cataract.[1] | |||||||||

| Capital | Memphis | ||||||||

| Common languages | Ancient Egyptian | ||||||||

| Religion | Ancient Egyptian religion | ||||||||

| Government | Divine, absolute monarchy | ||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||

• c. 2686 – c. 2649 BC | Djoser (first) | ||||||||

• c. 2184 – c. 2181 BC | Last king depends on the scholar, Neitiqerty Siptah (6th Dynasty) or Neferirkare (7th/8th Dynasty) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Began | c. 2686 BC | ||||||||

• Ended | c. 2181 BC | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 2500 BC | 1.6 million[2] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| History of Egypt |

|---|

|

|

|

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning c. 2700–2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourth Dynasty, such as King Sneferu, under whom the art of pyramid-building was perfected, and the kings Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure, who commissioned the construction of the pyramids at Giza.[3] Egypt attained its first sustained peak of civilization during the Old Kingdom, the first of three so-called "Kingdom" periods (followed by the Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom), which mark the high points of civilization in the lower Nile Valley.[4]

The concept of an "Old Kingdom" as one of three "golden ages" was coined in 1845 by the German Egyptologist Baron von Bunsen, and its definition evolved significantly throughout the 19th and the 20th centuries.[5] Not only was the last king of the Early Dynastic Period related to the first two kings of the Old Kingdom, but the "capital", the royal residence, remained at Ineb-Hedj, the Egyptian name for Memphis. The basic justification for separating the two periods is the revolutionary change in architecture accompanied by the effects on Egyptian society and the economy of large-scale building projects.[4]

The Old Kingdom is most commonly regarded as the period from the Third Dynasty to the Sixth Dynasty (2686–2181 BC). Information from the Fourth to the Sixth Dynasties of Egypt is scarce, and historians regard the history of the era as literally "written in stone" and largely architectural in that it is through the monuments and their inscriptions that scholars have been able to construct a history.[3] Egyptologists also include the Memphite Seventh and Eighth Dynasties in the Old Kingdom as a continuation of the administration, centralized at Memphis. While the Old Kingdom was a period of internal security and prosperity, it was followed by a period of disunity and relative cultural decline referred to by Egyptologists as the First Intermediate Period.[6] During the Old Kingdom, the King of Egypt (not called the Pharaoh until the New Kingdom) became a living god who ruled absolutely and could demand the services and wealth of his subjects.[7]

Under King Djoser, the first king of the Third Dynasty of the Old Kingdom, the royal capital of Egypt was moved to Memphis, where Djoser established his court. A new era of building was initiated at Saqqara under his reign. King Djoser's architect, Imhotep, is credited with the development of building with stone and with the conception of the new architectural form, the step pyramid.[7] The Old Kingdom is best known for a large number of pyramids constructed at this time as burial places for Egypt's kings.

History

[edit]Rise of the Old Kingdom

[edit]The first King of the Old Kingdom was Djoser (sometime between 2691 and 2625 BC) of the Third Dynasty, who ordered the construction of a pyramid (the Step Pyramid) in Memphis' necropolis, Saqqara. An important person during the reign of Djoser was his vizier, Imhotep.

It was in this era that formerly independent ancient Egyptian states became known as nomes, under the rule of the king. The former rulers were forced to assume the role of governors or otherwise work in tax collection. Egyptians in this era believed the king to be the incarnation of Horus, linking the human and spiritual worlds. Egyptian views on the nature of time during this period held that the universe worked in cycles, and the Pharaoh on earth worked to ensure the stability of those cycles. They also perceived themselves as specially selected people.[8]

-

The Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara.

-

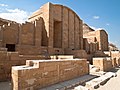

The Temple of Djoser at Saqqara

-

The head of a King, c. 2650–2600 BC, Brooklyn Museum. The earliest representations of Egyptian Kings are on a small scale. From the Third Dynasty, statues were made showing the ruler life-size. This head wearing the crown of Upper Egypt is larger than human scale.[9]

Height of the Old Kingdom

[edit]

The Old Kingdom and its royal power reached a zenith under the Fourth Dynasty (2613–2494 BC). King Sneferu, the first king of the Fourth Dynasty, held territory from ancient Libya in the west to the Sinai Peninsula in the east, to Nubia in the south. An Egyptian settlement was founded at Buhen in Nubia which endured for 200 years.[10] After Djoser, Sneferu was the next great pyramid builder. He commissioned the building of not one, but three pyramids. The first is called the Meidum Pyramid, named for its location in Egypt. Sneferu abandoned it after the outside casing fell off of the pyramid. The Meidum pyramid was the first to have an above-ground burial chamber.[11]

Using more stones than any other Pharaoh, he commissioned the three pyramids: a now collapsed pyramid in Meidum, the Bent Pyramid at Dahshur, and the Red Pyramid, at North Dahshur. However, the full development of the pyramid style of building was reached not at Saqqara, but during the building of the Great Pyramids at Giza.[12]

Sneferu was succeeded by his son, Khufu (2589–2566 BC), who commissioned the Great Pyramid of Giza. After Khufu's death, his sons Djedefre (2566–2558 BC) and Khafre (2558–2532 BC) may have quarrelled. The latter commissioned the second pyramid and (in traditional thinking) the Great Sphinx of Giza. Recent re-examination of evidence has led Egyptologist Vassil Dobrev to propose that the Sphinx was commissioned by Djedefre as a monument to his father Khufu.[13]Alternatively, the Sphinx has been proposed to be the work of Khafre and Khufu himself.

There were military expeditions into Canaan and Nubia, with Egyptian influence reaching up the Nile into what is today Sudan.[14] The later kings of the Fourth Dynasty were Menkaure (2532–2504 BC), who commissioned the smallest of the three great pyramids in Giza; Shepseskaf (2504–2498 BC); and, perhaps, Djedefptah (2498–2496 BC).

Fifth Dynasty

[edit]The Fifth Dynasty (2494–2345 BC) began with Userkaf (2494–2487 BC) and was marked by the growing importance of the cult of sun god Ra. Consequently, fewer efforts were devoted to the construction of pyramid complexes than during the Fourth Dynasty and more to the construction of sun temples in Abusir. Userkaf was succeeded by his son Sahure (2487–2475 BC), who commanded an expedition to Punt. Sahure was in turn succeeded by Neferirkare Kakai (2475–2455 BC), who was Sahure's son. Neferirkare introduced the prenomen in the royal titulary. He was followed by two short-lived kings, his son Neferefre (2455–2453 BC) and Shepseskare, the latter of uncertain parentage.[15] Shepseskare may have been deposed by Neferefre's brother Nyuserre Ini (2445–2421 BC), a long-lived pharaoh who commissioned extensively in Abusir and restarted royal activity in Giza.

The last pharaohs of the dynasty were Menkauhor Kaiu (2421–2414 BC), Djedkare Isesi (2414–2375 BC), and Unas (2375–2345), the earliest ruler to have the Pyramid Texts inscribed in his pyramid.

Egypt's expanding interests in trade goods such as ebony, incense such as myrrh and frankincense, gold, copper, and other useful metals inspired the ancient Egyptians to build suitable ships for navigation of the open sea. They traded with Lebanon for cedar and travelled the length of the Red Sea to the Kingdom of Punt- modern-day Eritrea—for ebony, ivory, and aromatic resins.[16] Shipbuilders of that era did not use pegs (treenails) or metal fasteners, but relied on the rope to keep their ships assembled. Planks and the superstructure were tightly tied and bound together. This period also witnessed direct trade between Egypt and its Aegean neighbors and Anatolia.[17]

The rulers of the dynasty sent expeditions to the stone quarries and gold mines of Nubia and the mines of Sinai.[18][19][20][21] there are references and depictions of military campaigns in Nubia and Asia.[22][23][24]

Decline into the First Intermediate Period

[edit]The sixth dynasty peaked during the reigns of Pepi I and Merenre I with flourishing trade, several mining and quarrying expeditions and major military campaigns. Militarily, aggressive expansion into Nubia marked Pepi I's reign.[25][26] At least five military expeditions were sent into Canaan.[27]

There is evidence that Merenre was not only active in Nubia like Pepi I but also sent officials to maintain Egyptian rule over Nubia from the northern border to the area south of the third cataract.[27]

During the Sixth Dynasty (2345–2181 BC) the power of the pharaoh gradually weakened in favor of powerful nomarchs (regional governors). These no longer belonged to the royal family and their charge became hereditary, thus creating local dynasties largely independent from the central authority of the Pharaoh. However, Nile flood control was still the subject of very large works, including especially the canal to Lake Moeris around 2300 BC, which was likely also the source of water to the Giza pyramid complex centuries earlier.

Internal disorders set in during the incredibly long reign of Pepi II (2278–2184 BC) towards the end of the dynasty. His death, certainly well past that of his intended heirs, might have created succession struggles. The country slipped into civil wars mere decades after the close of Pepi II's reign.

The final blow was the 22nd century BC drought in the region that resulted in a drastic drop in precipitation. For at least some years between 2200 and 2150 BC, this prevented the normal flooding of the Nile.[28]

Whatever its cause, the collapse of the Old Kingdom was followed by decades of famine and strife. An important inscription on the tomb of Ankhtifi, a nomarch during the early First Intermediate Period, describes the pitiful state of the country when famine stalked the land.

Art

[edit]The most defining feature of ancient Egyptian art is its function, as that was the entire purpose of creation. Art was not made for enjoyment in the strictest sense, but rather served a role of some kind in Egyptian religion and ideology.[29] This fact manifests itself in the artistic style, even as it evolved over the dynasties. The three primary principles of that style, frontality, composite composition, and hierarchy scale, illustrate this quite well.[29] These characteristics, initiated in the Early Dynastic Period[30] and solidified during the Old Kingdom, persisted with some adaptability throughout the entirety of ancient Egyptian history as the foundation of its art.[31]

Frontality, the first principle, indicates that art was viewed directly from the front. One was meant to approach a piece as they would a living individual, for it was meant to be a place of manifestation. The act of interaction would bring forth the divine entity represented in the art.[29] It was therefore imperative that whoever was represented be as identifiable as possible. The guidelines developed in the Old Kingdom and the later grid system developed in the Middle Kingdom ensured that art was axial, symmetrical, proportional, and most importantly reproducible and therefore recognizable.[33] Composite composition, the second principle, also contributes to the goal of identification. Multiple perspectives were used in order to ensure that the onlooker could determine precisely what they saw.[29]

Though Egyptian art almost always includes descriptive text, literacy rates were not high, so the art gave another method for communicating the same information. One of the best examples of composite composition is the human form. In most two-dimensional relief, the head, legs, and feet are seen in profile, while the torso faces directly front. Another common example is an aerial view of a building or location.[29] The third principle, the hierarchy of scale, illustrates relative importance in society. The larger the figure, the more important the individual. The king is usually the largest, aside from deities. The similarity in size equated to similarity in position. However, this is not to say that physical differences were not shown as well. Women, for example, are usually shown as smaller than men. Children retain adult features and proportions but are substantially smaller in size.[29]

Aside from the three primary conventions, there are several characteristics that can help date a piece to a particular time frame. Proportions of the human figure are one of the most distinctive, as they vary between kingdoms.[33] Old Kingdom male figures have characteristically broad shoulders and a long torso, with obvious musculature. On the other hand, females are narrower in the shoulders and waist, with longer legs and a shorter torso.[33] However, in the Sixth Dynasty, the male figures lose their muscularity and their shoulders narrow. The eyes also tend to get much larger.[29]

In order to help maintain the consistency of these proportions, the Egyptians used a series of eight guidelines to divide the body. They occurred at the following locations: the top of the head, the hairline, the base of the neck, the underarms, the tip of the elbow or the bottom of the ribcage, the top of the thigh at the bottom of the buttocks, the knee, and the middle of the lower leg.[33]

From the soles of the feet to the hairline was also divided into thirds, one-third between the soles and the knee, another third between the knee and the elbow, and the final third from the elbow to the hairline. The broad shoulders that appeared in the Fifth Dynasty constituted roughly that one-third length as well.[33] These proportions not only help with the identification of representations and the reproduction of art but also tie into the Egyptian ideal of order, which tied into the solar aspect of their religion and the inundations of the Nile.[29]

Though the above concepts apply to most, if not all, figures in Egyptian art, there are additional characteristics that applied to the representations of the king. Their appearance was not an exact rendering of the king's visage, though kings are somewhat identifiable through looks alone. Identification could be supplied by inscriptions or context.[29] A huge, more important part of a king's portrayal was about the idea of the office of kingship,[29] which were dependent on the time period. The Old Kingdom was considered a golden age for Egypt, a grandiose height to which all future kingdoms aspired.[35]

As such, the king was portrayed as young and vital, with features that agreed with the standards of beauty of the time. The musculature seen in male figures was also applied to kings. A royal rite, the jubilee run which was established during the Old Kingdom, involved the king running around a group of markers that symbolized the geographic borders of Egypt. This was meant to be a demonstration of the king's physical vigor, which determined his capacity to continue his reign.[35] This idea of kingly youth and strength were pervasive in the Old Kingdom and thus shown in the art.[31]

The sculpture was a major product of the Old Kingdom. The position of the figures in this period was mostly limited to sitting or standing, either with feet together or in the striding pose. Group statues of the king with either gods or family members, typically his wife and children, were also common.[30]

It was not just the subject of sculpture that was important, but also the material: The use of hard stone, such as gneiss, graywacke, schist, and granite, was relatively common in the Old Kingdom.[36] The color of the stone had a great deal of symbolism and was chosen deliberately.[29] Four colors were distinguished in the ancient Egyptian language: black, green, red, and white.[36] Black was associated with Egypt due to the color of the soil after the Nile flood, green with vegetation and rebirth, red with the sun and its regenerative cycle, and white with purity.[29]

The statue of Menkaure with Hathor and Anput is an example of a typical Old Kingdom sculpture. The three figures display frontality and axiality, while fitting with the proportions of this time period. The graywacke came from the Eastern Desert in Egypt[37] and is therefore associated with rebirth and the rising of the sun in the east.

Gallery

[edit]-

King khufu statue at Cairo museum.

-

King khafre statue at Cairo museum

-

Greywacke statue of Menkaure and Queen Khamerernebty II at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

-

Kaaper around 2500 BC

-

Majordomo Keki statue,6th dynasty at Louvre museum.

References

[edit]- ^ Grimal, Nicolas (1994). A History of Ancient Egypt. Wiley-Blackwell (July 19, 1994). p. 85.

- ^ Steven Snape (16 March 2019). "Estimating Population in Ancient Egypt". Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Old Kingdom of Egypt". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2017-12-04.

- ^ a b Malek, Jaromir. 2003. "The Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2160 BC)". In The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, edited by Ian Shaw. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192804587, p.83

- ^ Schneider, Thomas (27 August 2008). "Periodizing Egyptian History: Manetho, Convention, and Beyond". In Klaus-Peter Adam (ed.). Historiographie in der Antike. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 181–197. ISBN 978-3-11-020672-2.

- ^ Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times, pp. 55 & 60.

- ^ a b Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times, p. 56.

- ^ Herlin, Susan J. (2003). "Ancient African Civilizations to ca. 1500: Pharaonic Egypt to Ca. 800 BC". p. 27. Archived from the original on August 23, 2003. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ Bothmer, Bernard (1974). Brief Guide to the Department of Egyptian and Classical Art. Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Museum. p. 22.

- ^ "The Old Kingdom (c. 2575–c. 2130 BCE) and the First Intermediate period (c. 2130–1938 BCE)". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^ "Ancient Egypt – the Archaic Period and Old Kingdom". Penfield High School. Retrieved 2017-12-04.

- ^ Carl Roebuck (1984), The World of Ancient Times, p. 57.

- ^ Fleming, Nic (14 December 2004). "I have solved riddle of the Sphinx, says Frenchman". The Telegraph. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ p.5, The Collins Encyclopedia of Military History (4th edition, 1993), Dupuy & Dupuy.

- ^ Miroslav Verner: Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology, Archiv Orientální, Volume 69: 2001

- ^ Franziska Grathwol, Christian Roos, Dietmar Zinner, Benjamin Hume, Stéphanie M Porcier, Didier Berthet, Jacques Cuisin, Stefan Merker, Claudio Ottoni, Wim Van Neer (2023), "Adulis and the transshipment of baboons during classical antiquity", eLife, 12, elifsciences, doi:10.7554/eLife.87513, PMC 10597581, PMID 37767965

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Grimal, Nicolas (1994). A History of Ancient Egypt. Wiley-Blackwell (July 19, 1994). p. 76.

- ^ Grimal, Nicolas (1994). A History of Ancient Egypt. Wiley-Blackwell (July 19, 1994). pp. 76, 79.

- ^ Verner, Miroslav (2001b). "Old Kingdom: An Overview". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 585–591. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- ^ Shaw, Ian (2003). "New fieldwork at Gebel el-Asr: "Chephren's diorite quarries"". In Hawass, Zahi; Pinch Brock, Lyla (eds.). Egyptology at the Dawn of the Twenty-first Century: Archaeology. Cairo, New York: American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-424-715-6.

- ^ Klemm, Rosemarie; Klemm, Dietrich (2013). Gold and gold mining in ancient Egypt and Nubia : geoarchaeology of the ancient gold mining sites in the Egyptian and Sudanese eastern deserts. Natural science in archaeology. Berlin; New-York: Springer. ISBN 978-1-283-93479-4.

- ^ Verner, Miroslav (2001b). "Old Kingdom: An Overview". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 588. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- ^ "Siege Scenes of the Old Kingdom". Archived from the original on 2022-02-04. Retrieved 2022-02-04.

- ^ Baker, Darrell (2008). The Encyclopedia of the Pharaohs: Volume I – Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty 3300–1069 BC. Stacey International. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-905299-37-9.

- ^ Hayes, William (1978). The Scepter of Egypt: A Background for the Study of the Egyptian Antiquities in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 1, From the Earliest Times to the End of the Middle Kingdom. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 122. OCLC 7427345.

- ^ Smith, William Stevenson (1971). "The Old Kingdom of Egypt and the Beginning of the First Intermediate Period". In Edwards, I. E. S.; Gadd, C. J.; Hammond, N. G. L. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 1, Part 2. Early History of the Middle East (3rd ed.). London, New york: Cambridge University Press. pp. 191–194. ISBN 9780521077910. OCLC 33234410.

- ^ a b Grimal, Nicolas (19 July 1994). A History of Ancient Egypt. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 85.

- ^ Jean-Daniel Stanley; et al. (2003). "Nile flow failure at the end of the Old Kingdom, Egypt: Strontium isotopic and petrologic evidence" (PDF). Geoarchaeology. 18 (3): 395–402. doi:10.1002/gea.10065. S2CID 53571037.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Robins, Gay (2008). The Art of Ancient Egypt. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- ^ a b Sourouzian, Hourig (2010). A Companion to Ancient Egypt. Vol. I. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. pp. 853–881.

- ^ a b Arnold, Dorothea (1999). When the Pyramids Were Built: Egyptian Art of the Old Kingdom. The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Rizzoli International Publications Inc. pp. 7–17.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Museum".

- ^ a b c d e Robins, Gay (1994). Proportion, and Style in Ancient Egyptian Art. University of Texas Press.

- ^ "Statue of Menkaure with Hathor and Cynopolis". The Global Egyptian Museum.

- ^ a b Malek, Jaromir (1999). Egyptian Art. London: Phaidon Press Limited.

- ^ a b Morgan, Lyvia (2011). "Enlivening the Body: Color and Stone Statues in Old Kingdom Egypt". Notes in the History of Art. 30 (3): 4–11. doi:10.1086/sou.30.3.23208555. S2CID 191369829.

- ^ Klemm, Dietrich (2001). "The Building Stones of Ancient Egypt: A Gift of its Geology". African Earth Sciences. 33 (3–4): 631–642. Bibcode:2001JAfES..33..631K. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.111.9099. doi:10.1016/S0899-5362(01)00085-9.

Further reading

[edit]- Brewer, Douglas J. (2005). Ancient Egypt: foundations of a civilization. Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-77253-3.

- Callender, Gae (1998). Egypt in the old kingdom: an introduction. Melbourne: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-81226-0.

- Kanawati, Naguib (1980). Governmental reforms in old Kingdom Egypt. Modern Egyptology series. Warminster, England: Aris & Phillips. ISBN 978-0-85668-168-4.

- Kanawati, Naguib; Woods, Alexandra; Alexakis, Effy, eds. (2009). Artists of the Old Kingdom: techniques and achievements. Cairo: Supreme Council of Antiquities Press. ISBN 978-977-437-985-7.

- Lehner, Mark (1997). The complete pyramids. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05084-2.

- Málek, Jaromír; Forman, Werner (1986). In the shadow of the pyramids: Egypt during the Old Kingdom. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2027-0.

- McFarlane, Ann; Mourad, Anna-Latifa (2012). Behind the scenes: daily life in Old Kingdom Egypt. Studies. North Ryde: Australian Centre for Egyptology. ISBN 978-0-85668-860-7.

- O'Neill, John P.; Allen, James P., eds. (1999). Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-907-9.

- Papazian, Hratch (2012). Domain of Pharaoh: the structure and components of the economy of Old Kingdom Egypt. Hildesheimer Ägyptologische Beiträge. Hildesheim: Gerstenberg. ISBN 978-3-8067-8761-0. OCLC 788217545.

- Ryholt, K. S. B. (1997). The political situation in Egypt during the second intermediate period, c. 1800-1550 B.C. CNI publications. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 978-87-7289-421-8.

- Sowada, Karin N.; Grave, Peter (2009). Egypt in the Eastern Mediterranean during the Old Kingdom: an archaeological perspective. Orbis biblicus et orientalis. Fribourg, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-7278-1649-9. OCLC 428025036. S2CID 127449010.

- Kanawati, Naguib; Strudwick, Nigel (1992). The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom: The Highest Titles and Their Holders (PDF). Studies in egyptology. Vol. 78. London: KPI. doi:10.2307/3822094. ISBN 978-0-7103-0107-9. JSTOR 3822094. S2CID 69046660.

- Warden, Leslie Anne (2014). Pottery and economy in Old Kingdom Egypt. Culture and history of the ancient Near East. Leiden ; Boston: Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-25984-3.

- Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (2001). Early dynastic Egypt. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-26011-4.

External links

[edit]- The Fall of the Egyptian Old Kingdom from BBC History

- Middle East on The Matrix: Egypt, The Old Kingdom – Photographs of many of the historic sites dating from the Old Kingdom

- Old Kingdom of Egypt- Aldokkan

![The head of a King, c. 2650–2600 BC, Brooklyn Museum. The earliest representations of Egyptian Kings are on a small scale. From the Third Dynasty, statues were made showing the ruler life-size. This head wearing the crown of Upper Egypt is larger than human scale.[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5c/Head_of_a_King%2C_ca._2650-2600_B.C.E..jpg/91px-Head_of_a_King%2C_ca._2650-2600_B.C.E..jpg)