Christianity in Afghanistan

| Christianity by country |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Religion in Afghanistan |

|---|

|

| Majority |

| Sunni Islam |

| Minority |

| Historic/Extinct |

| Controversy |

This article needs to be updated. (August 2021) |

Christians have historically comprised a small community in Afghanistan. The total number of Christians in Afghanistan is currently estimated to be between 15,000 and 20,000 according to International Christian Concern. Almost all Afghan Christians are converts from Islam. The Pew Research Center estimates that 40,000 Afghan Christians were living in Afghanistan in 2010.[1] The Islamic Republic of Afghanistan did not recognize any Afghan citizen as being a Christian, with the exception of many expatriates (although, Rula Ghani, the country's First Lady from 2014 until 2021, is a Maronite Christian from Lebanon).[2][3] Christians of Muslim background communities can be found in Afghanistan, estimated between 500-8,000,[4][5] or between 10,000 to 12,000.[6]

Current status

[edit]Taliban Rule

[edit]Afghanistan was number one on Open Doors’ 2022 World Watch List, an annual ranking of the 50 countries where Christians face the most extreme persecution.[7] In 2023 the country was ranked number 9;[8] this was mainly due to the Taliban focusing on politics rather than non-Muslims.

After the Taliban retook control of the country in August 2021, the USCIRF warned that Christians in the country were in "extreme danger."[9] Many fled and sought asylum, while the few Christians left in the country reported that they were in hiding from Taliban sweeps. The Taliban falsely claims that there are "no Christians" remaining in Afghanistan.[10]

Closet Christians

[edit]Despite societal restrictions, many sources claim that there is a secret underground community of Afghan Christians living in Afghanistan.[11][12] The US Department of State has stated that estimates of the size of this group range from 500 to 8,000 individuals.[12] However, estimates of the size of the Afghan Christian community in Afghanistan are not reliable.[13] Due to Afghanistan's hostile legal environment, Afghan Christians secretly practice their faith in private homes.[14][13] The complete Bible is available online in Pashto, in the Yusufzai dialect.[15]

Christian converts

[edit]There are a number of Afghan Christians (both converts and their descendants) who live outside Afghanistan, including Christian communities in India,[16] the United States,[17] the United Kingdom,[18] Canada,[19] Austria,[20] Finland,[21] and Germany.[22][23]

History

[edit]The Apostle Thomas and early Christianity

[edit]

According to the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 2:9) in the Bible ethnic Jews and converts to Judaism from the Parthian Empire (which included parts of western Afghanistan[24][25][26]) were present at Pentecost. According to Eusebius' record, the apostles Thomas and Bartholomew were assigned to Parthia.[27]

A legend that is contained in the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas and other ancient documents suggests that Saint Thomas preached in Bactria, an ancient region in Central Asia that was located on flat land which straddles modern-day northern Afghanistan.[28] An early third-century Syriac work known as the Acts of Thomas[27] connects the apostle's ministry with two kings, one in the north and the other in the south. According to the Acts, Thomas was at first reluctant to accept this mission, but the Lord appeared to him in a night vision and compelled him to accompany an Indian merchant, Abbanes (or Habban), to his native place in northwest India. There, Thomas found himself in the service of the Indo-Parthian (Southern Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Northern India) King, Gondophares. The Apostle's ministry resulted in many conversions throughout the kingdom, including the king and his brother.[27]

Bardaisan, writing in about 196, speaks of Christians throughout Media, Parthia, and Bactria[29] and, according to Tertullian (c.160–230), there were already a number of bishoprics within the Persian Empire by 220.[30] By the time of the establishment of the Second Persian Empire (AD 226), there were bishops of the Church of the East in northwest India, Afghanistan, and Baluchistan, with laymen and clergy alike engaging in missionary activity.[27]

The Church of the East

[edit]In 409, the Church of the East (also sometimes called the Nestorian Church) received state recognition from King Yazdegerd I[31] (reigned 399–409), of the Iranian Sassanid Empire which ruled what is now Afghanistan from 224 to 579.

In 424, Bishop Afrid of Sakastan, an area covering southern Afghanistan including Zaranj and Kandahar,[32] attended the Synod of Dadyeshu.[33] This synod was one of the most important councils of the Church of the East and determined that there would be no appeal of their disciplinary or theological problems to any other power, especially not to any church council in the Roman Empire.[34]

The year 424 also marks the establishment of a bishop in Herat.[35] In the 6th century, Herat was seen as a Metropolitan See the Apostolic Church of the East,[35][36] and from the 9th century Herat was also the see of the Syriac Orthodox Metropolitan.[36] The significance of the Christian community in Herat can be seen in that till today there is a district outside of the city named Injil,[37] The Arabic/Dari/Pashto word for Gospel. The Christian community was present in Herat until at least 1310.[38]

The Apostolic Church of the East established bishops in nine cities in Afghanistan including Herat (424–1310), Farah (544–1057),[38] Zaranj (544), Bushanj (585), Badghis (585) Kandahar, and Balkh.[35][38] There are also ruins of a Nestorian convent from the 6th–7th centuries a short distance from Panj, Tajikistan on the north bank of the Amu Darya very close to the Afghan border, near Kunduz. The complex was discovered and identified by Soviet archeologists in 1967. It consists of dozens of small rooms carved into a rock formation.[40]

Ahmed Tekuder, also known as Sultan Ahmad (reigned 1282–1284) was the sultan of the Ilkhan Empire, a Mongol Empire that stretched from eastern Turkey to Pakistan and covered most of Afghanistan. Tekuder was born Nicholas Tekuder Khan as a Nestorian Christian; however, Tekuder later embraced Islam[41] and changed his name to Ahmed Tekuder. When Tekuder assumed the throne in 1282, he turned the Ilkhan empire into a sultanate. Tekudar zealously propagated his new faith and sternly required his ranking offices to do the same. The Ilkhan Empire ultimately adopted Islam as a state religion in 1295. The Church of the East was almost completely eradicated across Afghanistan and Persia during the reign of Timur (1336–1405).[42]

Early Jesuit explorers

[edit]In 1581 and 1582 respectively, the Jesuit and Spanish Montesserat and the Portuguese Bento de Góis were warmly welcomed by the Islamic Emperor Akbar, but there was no lasting presence by the Jesuits in the country.[43][44]

The Armenian Apostolic Church

[edit]There were Armenian merchants living in Kabul as early as 1667 who were in contact with the Jesuits in Mughal (modern day India).[45] It is unclear if these Armenian merchants were Christians but their presence suggests an Armenian community in Kabul in the 17th century. Kabul was under the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the Armenian Apostolic Church Perso-Indian diocese in New Julfa, Esfahan (modern day Iran),[46] which sent Armenian priests to the community; however, no Armenian priest came after 1830.[47]

In 1755, Jesuit missionaries to Lahore Joseph Tiefenthaler reported that Sultan Ahmad Shah Bahadur took several Armenian gunmakers from Lahore to Kabul.[48] Anglican missionary Joseph Wolff preached to their descendants in Kabul in Persian in 1832; by his account, the community numbered about 23 people.[47][49] In 1839, when Lord Keane marched to Kabul, the Chaplain, the Rev. G. Pigott, baptised two of the children at the Armenian church.[50] And in 1842, the Rev. J. N. Allen, Chaplain to General William Nott's force, baptized three others.[46][51]

The only reported baptism of an ethnic Afghan in the Armenian Church was said to be a robber who broke into the church through the roof and fell three times while attempting to leave with the valuable silver vessels stored there. When he was discovered, he begged for mercy and later asked to be baptized.[52] The Armenian church building near Bala Hissar was destroyed during the Second Anglo-Afghan War by British troops; the community received compensation from the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office for their loss, but the church was never rebuilt.

As late as 1870, British reports showed 18 Armenian Christians remaining in Kabul.[47] In 1896, Abdur Rahman Khan, Emir of Afghanistan, even sent a letter to the Armenian community at Calcutta, India (now Kolkata), asking that they send ten or twelve families to Kabul to "relieve the loneliness" of their fellow Armenians, whose numbers had continued to dwindle.[53] However, despite an initial reply of interest, in the end, none of the Armenians of Calcutta accepted the offer.[54] The following year, the final remnants of the Armenians were expelled after a letter from Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II to the Afghan ruler questioning the loyalty of the Armenians.[55]

The Armenians of Kabul took refuge in Peshawar. These refugees carried their religious books and ancient manuscripts with them. An article on this issue in the Englishman (Calcutta) dated 11 February 1907 stated: "These people in the time of the late Ameer Abdul Rahman had dwindled down to ten families. They were, for reasons unknown, banished to Peshawar and brought down with them a collection of manuscripts said to be of immense antiquity. Indeed, they are so old that none of the families possessing them are able to read them. In any case an examination by experts of the manuscripts now said to be in Peshawar, should yield some valuable results. The families themselves are unaware of the history of the first settlement in Kabul, except that it dates back to the very earliest times."[56] Armenian Archbishop Sahak Ayvadian, after this publication went to Peshawar for a pastoral visit to these Armenians as well as to examine the books and manuscripts. On his return to Calcutta he presented some books to the Armenian Church Library, which he had obtained from the refugees.[57]

20th century onwards

[edit]Until 2021, when all minority religious institutions ceased to be recognized, the only legally recognized church in Afghanistan was within the compound of the Italian embassy. Italy was the first country to recognize Afghanistan's independence in 1919, and the Afghan government asked how it could thank Italy. Rome requested the right to build a Catholic chapel, which was being requested by international technicians then living in the Afghan capital. A clause giving Italy the right to build a chapel within its embassy was included in the Italian-Afghan treaty of 1921, and that same year the Barnabites arrived to start giving pastoral care.[58] The actual pastoral work began in 1933 when the chapel international technicians had asked for was built.[59] In the 1950s, the simple cement chapel was finished.[60]

From 1990 to 1994, Father Giuseppe Moretti served as the only Catholic priest in Afghanistan,[61] but he was forced to leave in 1994 after being hit with shrapnel when the Italian embassy was attacked during the civil war, and he had to return to Italy.[62] After 1994, the Little Sisters of Jesus were the only Catholic religious workers who were allowed to remain in Afghanistan, because they had been there since 1955, and their work was renowned.[63] An official from President Mohammed Najibullah's government in 1992 visited Moretti for planning a new church compound, but nothing came out of it as Najibullah was shortly afterwards deposed by the rebels during the conflict.[64]

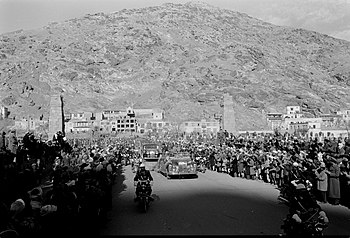

In 1959, US President Dwight D. Eisenhower visited Afghanistan. The Islamic Center of Washington had recently been built in Washington, DC, for the Muslim diplomats there and President Eisenhower requested permission from King Zahir Shah to construct a Protestant church in Kabul on a reciprocal basis for the use of the diplomatic corp and expatriate community in Afghanistan. Christians from all around the world contributed to its construction. At its dedication, the cornerstone which was carved in Afghan alabaster marble read: "To the glory of God 'Who loves us and has freed us from our sins by His blood' this building is dedicated as 'a house of prayer for all nations' in the reign of H.M. Zahir Shah, May 17, 1970 A.D., 'Jesus Christ Himself being the Chief Cornerstone'."[65][66] However, the church building was destroyed 17 June 1973,[66] during the republican coup d'état by Mohammed Daoud Khan against the monarchy. Since then, no place of worship has been authorized for Protestant Christians.

Christians were persecuted after the Taliban came to power in the mid-1990s.[67] The number of converts to Christianity increased as the U.S. presence increased after the fall of the Taliban in 2001. Most of the Christian converts lived in urban areas, so the threat from the Taliban was minimal. But many Christian converts started fleeing Afghanistan (mostly to India) around 2005, fearing their identities might become public.[68] A 2015 study estimated some 3,300 believers in Christ from a Muslim background living in the country.[69]

Under the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, the Constitution of Afghanistan allowed the practice of religions other than Islam, as long as it was within the legal framework of Islamic laws and did not threaten the Islamic religion. However Muslims who converted to Christianity were subjected to societal and official pressure,[14][70] which may lead to confiscation of property, imprisonment, or death.[71] "Christian minority has never been known or registered here,” Inamullah Samangani, a Taliban spokesman told VOA in 2022. He further added “There are only Sikh and Hindu religious minority in Afghanistan that are completely free and safe to practice their religion,”[72]

Anti-Christian incidents since 2001

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (October 2017) |

- On 5 August 2001, 24 workers for the NGO Shelter Now International were arrested by the ruling Taliban. The charity built homes for refugees and the poor.[73] 16 were Afghans and 8 were westerners. The workers were eventually freed after a rescue mission in November 2001. The westerners had been six women and two men, from Germany, America, and Australia. The staff of Shelter Now had been accused of converting Afghan Muslims to Christianity.[73][74][75]

- In 2002, Afghanistan adopted a new press law that contained a sanction against the publication of "matters contrary to the principles of Islam or offensive to other religions and sects."[76]

- In 2003, Mullah Dadullah (Pashto: ملا دادالله آخوند), a top Taliban commander, said that they would continue to fight until the "Jews and Christians, all foreign crusaders" were expelled from Afghanistan.[77]

- In January 2004, Afghanistan adopted a new constitution that provides for the freedom of non-Muslim religious groups to exercise their faith and declares that the state will abide by the UN Charter, international treaties, international conventions, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. However, the constitution does not extend explicit protections for the right to freedom of religion or belief to every individual, particularly to individual Muslims, the overwhelming majority of Afghanistan's population, or minority religious communities.[78]

- In 2005 President Hamid Karzai showed his respects by attending the funeral of Pope John Paul II.[79]

- In February 2006, an Afghan Christian, Abdul Rahman (Persian: عبدالرحمن) (born 1965) was arrested in February 2006 and threatened with the death penalty for converting to Christianity.[80][81] On 26 March 2006, under heavy pressure from foreign governments, the court returned his case to prosecutors, citing "investigative gaps" and suspicions that he was 'mentally unbalanced'.[82][83][84] He was released from prison to his family on the night of 27 March.[85] On 29 March, Abdul Rahman arrived in Italy after the Italian government offered him asylum.[86]

- On 19 July 2007, 23 South Korean missionaries were captured and held hostage by members of the Taliban while passing through Ghazni Province. Two male hostages were executed before the deal was reached between the Taliban and the South Korean government. The group, composed of sixteen women and seven men, was captured while traveling from Kandahar to Kabul by bus on a mission sponsored by the Saemmul Presbyterian Church.[87] Of the 23 hostages captured, two men, Bae Hyeong-gyu, a 42-year-old South Korean pastor of Saemmul Church, and Shim Seong-min, a 29-year-old South Korean man, were executed on 25 and 30 July, respectively. Later, with negotiations making progress, two women, Kim Gyeong-ja and Kim Ji-na were released on 13 August and the remaining 19 hostages on 29 and 30 August.[88]

- In September 2008, the Afghan parliament passed a new media law that prohibits works and materials that are contrary to the principles of Islam, works and materials offensive to other religions and sects, and propagation of religions other than Islam.[89]

- In October 2008 Gayle Williams (1974? – 20 October 2008), an aid worker for SERVE Afghanistan of joint British and South African nationality, was shot on her way to work in Kabul by two men on a motorbike. Zabiullah Mujahid, a spokesman for the Taliban, claimed responsibility for her death and said she had been killed "because she was working for an organization which was preaching Christianity in Afghanistan".[90]

- In May 2009, it was made public that Christian groups had published Bibles in the Pashtun language and the Dari language, intended to convert Afghans from Islam to Christianity.[91][92][93][94] The Bibles were sent to soldiers at the Bagram Air Base. American military authorities report that Bible distribution was not official policy, and when a chaplain became aware of the soldiers' plans the Bibles were confiscated and, eventually, burned.

- In March 2010 the remaining buildings on the leased property where the 1970 built Protestant church had stood were destroyed.[95] The buildings had been unofficially used by the international Christian community as a meeting place. The 99-year lease of the property which was paid for in gold in 1970 was not honored by the Afghan courts.[95]

- In June 2010 Noorin TV, a small Afghan television station, showed footage of men it said were reciting Christian prayers in Dari and being baptized. The television station said the men were Afghans who had converted to Christianity. Two humanitarian agencies, Norwegian Church Aid and Church World Service of the United States, were suspended after it was suggested in this report that they had converted Afghan Muslims to Christianity. Later Noorin TV confirmed that there was no evidence against the two agencies and that they had been named because of the word "church" in their names.[96] The report sparked anti-Christian protests in Kabul and in Mazar-e Sharif.[97] In parliament, Abdul Sattar Khawasi, a deputy of the lower house, called for Muslim converts to Christianity to be executed and Qazi Nazir Ahmad, a lawmaker from the western province of Herat, said killing a converted Muslim was "not a crime".[98] One of the men shown in the video, among the 25 Christians arrested was Said Musa (also spelled Sayed Mussa), an Afghan Red Cross worker, who was later sentenced to death for converting to Christianity.[99][100]

- On 5 August 2010, ten members of the International Assistance Mission Nuristan Eye Camp team were killed in Kuran wa Munjan District of Badakhshan Province in Afghanistan.[101][102] The team was attacked as it was returning from Nuristan to Kabul. One team member was spared, the rest of the team were killed immediately. Those killed were six Americans, two Afghans, one Briton and one German.[103] Both Hizb-e Islami and the Taliban initially claimed responsibility for the attack,[102] accusing the doctors of proselytism and spying.[104][105][106] These claims were later refuted by Taliban leaders in Nuristan and Badakhshan, who stated that they had confirmed the dead were bona-fide aid workers, condemned the killings as murder, and offered their condolences to the families of those killed.[107] The attack was the deadliest strike against foreign aid workers in the Afghanistan war.[108][109][110][111][112] The killings underscored the suspicion Christian-affiliated groups face from some Afghans and government opponents and the wider risks faced by aid workers in the country.[113]

- On 9 August 2010, two Afghans and two aid workers were arrested for preaching Christianity in western Herat province. Two NGO workers were deported from the country and the Afghans were kept for longer period. After long negotiations, the government freed them in Kabul.

- In November 2010, Another man, Shoaib Assadullah Musawi, was jailed in the northern city of Mazar-i-Sharif after being accused of giving the New Testament to a friend, who then turned him in.[114] Shoaib Assadullah was freed from prison on 30 March 2011 and on 14 April 2011 received a passport and left Afghanistan.[115]

- In February 2011, International Christian Concern lauded the release of Said Musa (also spelled Sayed Mussa) an Afghan man who had been imprisoned for nine months for converting to Christianity.[116]

Freedom of Religion after 2021

[edit]The Taliban took back power in Sept 2021. A report in 2022 report noted that they had stated that the country is an Islamic emirate whose laws and governance must be consistent with sharia law. Non-Muslim minorities reported continued harassment from Muslims, while Baha’is and Christians continued to live in constant fear of exposure.[117]

In 2022, Freedom House rated Afghanistan’s religious freedom as 1 out of 4.[118]

In 2023, it was reported that violations against minorities had increased after September 2021. In particular many minorities fled to neighbouring countries such as Iran and Pakistan.[119]

See also

[edit]- Islam and other religions

- Christianity and Islam

- Catholic Church in Afghanistan

- History of the Jews in Afghanistan

- Islam in Afghanistan

- Religion in Afghanistan

- Freedom of religion in Afghanistan

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Global Christianity – A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Christian Population" (PDF). Pew Research Center.

- ^ Burger, John (13 January 2016). "Meet Rula Ghani, Afghanistan's Christian First Lady". Aleteia. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ "Afghanistan First Lady Rula Ghani Moves into the Limelight". BBC. 15 October 2014. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ A El Shafie, Majed (2012). Freedom Fighter: One Man's Fight for One Free World. Destiny Image Publishers. ISBN 9780768487732.

It estimated the Afghan Christian community ranges from 500 to 8,000 people. For all practical purposes, there are no native Afghan Christians; they are all converts from Islam who worship in secret to avoid being killed for apostasy..

- ^ The 2011 International Religious Freedom Repor. University of California Press. 2018. p. 86. ISBN 9780160905346.

all indigenous Christians ( whose numbers are impossible to determine but have been estimated by the State Department at 500-8,000 ) are converts from Islam

- ^ "Taliban Say No Christians Live in Afghanistan; US Groups Concerned". VOA News. 16 May 2022.

There is no official data available about Christianity in Afghanistan, but USCIRF, quoting ICC, has reported 10,000 to 12,000 Christian converts in the Muslim country.

- ^ "Afghanistan is number 1 on the World Watch List".

- ^ Open Doors website, retrieved 2023-08-28

- ^ "Christians in Extreme Danger in Afghanistan". USCIRF. 28 January 2022.

- ^ "Taliban Say No Christians Live in Afghanistan; US Groups Concerned". VOA. 16 May 2022. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "Christians in Afghanistan: A Community of Faith and Fear". Der Spiegel. 30 March 2006. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ^ a b USSD Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (2009). "International Religious Freedom Report 2009". Archived from the original on 30 November 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b USSD Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (2016). "International Religious Freedom Report 2016". Retrieved 23 January 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Lyons, Kate; Blight, Garry (27 July 2015). "Where in the world is the worst place to be a Christian?". The Guardian.

- ^ "Afghan Media Centre". afghanmediacentre.org. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ Faroquee, Neyaz (22 July 2013). "An Afghan Church Grows in Delhi". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

In a South Delhi neighborhood, the sound of a man reciting Dari, a Farsi dialect which is spoken in Afghanistan, over a loudspeaker which was attached to a modest two-story building, rose over the din of vegetable hawkers. The building was a church which was run by Afghan refugees who had converted to Christianity. The man was a young Afghan priest who was reading the Bible before a Sunday service was held in its basement. Between 200 and 250 Afghan converts from Islam to Christianity who feared persecution by the Afghan authorities and the Taliban have found refuge in Delhi.

- ^ "Afghan Christian Fellowship, Los Angeles". Afghanchurch.net. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ^ Mohammadi, Reza (6 March 2009). "Plight of an Afghan Christian". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "Iranian Christian Churches in Canada, Iranian Christian Church in Toronto Canada, Iranian Christian Church in Montreal Canada, Iranian Christian Church in Vancouver Canada, Persian Church in Canada, Farsi Church in Canada, farsi Church in Toronto, farsi Church in vancouver, Worldwide Directory of Iranian/Persian Christian Churches – Iranian Christian Churches in Toronto, Vancouver, Montreal". Farsinet.com. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ^ "کليسايی تعميدی افغان" [ABC About us]. Khudawand.com. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ^ Hundreds of asylum seekers in Finland converting from Islam to Christianity. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- ^ Muslims Converting to Christianity by the Hundreds in Finland. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- ^ Christian refugee converts in Germany face violent attacks. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- ^ "Map of Parthian Empire, 1st century BCE". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ "Afghanistan, Historical beginnings (to the 7th century CE)". Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ "Legendary horsemen and battlefield tacticians, willing to travel vast distances and strike at a moment's notice, the Parthians took advantage of the collapsing Seleucid Empire to carve out an empire during the late 3rd century BC to the 1st century AD that, at its peak, covered a vast region — from the Caspian Sea in the north to Syria in the west, the Persian Gulf in the south and the western half of present-day Afghanistan to the east —making it second only to the Roman Empire in size and economic might."CENTCOM Heritage/Cultural Advisory Group Training Module. "Parthian, Indo-Greek, Indo-Parthian, Yuezhi Invasion and Indo-Scythian Rule (circa 200 BC to circa 100 AD)". Colorado State University. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d A. E. Medlycott, India and The Apostle Thomas, pp.18–71; M. R. James, Apocryphal New Testament, pp.364–436; A. E. Medlycott, India and The Apostle Thomas, pp.1–17, 213–97; Eusebius, History, chapter 4:30; J. N. Farquhar, The Apostle Thomas in North India, chapter 4:30; V. A. Smith, Early History of India, p.235; L. W. Brown, The Indian Christians of St. Thomas, p.49-59

- ^ Merillat, Herbert Christian (1997). "Wandering in the East". The Gnostic Apostle Thomas. Archived from the original on 27 September 2004. Retrieved 11 August 2009.

- ^ "We are Christians by the one name of the Messiah. As regards our customs our brethren abstain from everything that is contrary to their profession. ... Parthian Christians do not take two wives. ... Our Bactrian sisters do not practice promiscuity with strangers. Persians do not take their daughters to wife. Medes do not desert their dying relations or bury them alive. Christians in Edessa do not kill their wives or sisters who commit fornication but keep them apart and commit them to the judgment of God. Christians in Hatra do not stone thieves" (quoted in Mark Dickens: The Church of the East Archived 25 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ http://Dickens[permanent dead link], Mark. Church of the East www.oxuscom.com/Church_of_the_East.pdf

- ^ Willison, Walker (1985). A history of the Christian church. Simon & Schuster. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-684-18417-3.

- ^ Sakastan

- ^ Sanasarian, Eliz (Summer–Fall 1998). "Babi-Bahais, Christians, and Jews in Iran". Journal of the Assyrian Academic Society. 31 (3–4): 615–624. JSTOR 4311193.

- ^ "Christianity in Iran, a Brief History". Culture of Iran. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ^ a b c "Location of Nestorian Bishops". Nestorian.org. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ^ a b "Chronology of Catholic Dioceses: Afghanistan" (in Norwegian). Katolsk.no. 15 May 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). www.aims.org.af. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2006. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b c "Asia at a Glance". Archived from the original on 18 August 2000. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- ^ A history of the crusades, By Steven Runciman, pg. 397

- ^ Maria Adelaide. "Nestorianism in Central Asia during the First Millennium: Archaeological Evidence" (PDF). Journal of the Assyrian Academic Society: 17/34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ A history of the crusades By Steven Runciman, pg. 397

- ^ Apostolic Church of the East

- ^ "Jesuits in Afghanistan?". SJ Electronic Information Service. 17 June 2005. Archived from the original on 14 May 2006. Retrieved 18 June 2006.

- ^ "After 400 years, Jesuits return to Afghanistan". Australian Jesuits. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 11 August 2009.

- ^ As cited in: M.J.Seth, Armenians in India, New Delhi-Bombay-Calcutta, Oxford & IHB Publishing Co., 1983, p 207 https://www.angelfire.com/hi/Azgaser/kabul.html

- ^ a b "Armenians in Kabul". Angelfire.com. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ^ a b c Seth 1992, p. 208

- ^ Seth 1992, p. 207

- ^ Travels and Adventures of The Rev. Joseph Wolff, D.D., LL.D., Vicar of Ile Brewers, Near Taunton; And Late Missionary to the Jews and Muhammadans in Persia, Bokhara, Cashmeer, etc. pg 362 1861 https://archive.org/stream/travelsofwolff00wolfuoft/travelsofwolff00wolfuoft_djvu.txt

- ^ The Rev. J. N. Allen's account of his visit to the Armenian Church at Cabul in 1842 states: "1842, 1 October.I went into the town and accompanied by Captain Boswell, 2nd Regiment, Bengal N.I. set forth to make inquiries respecting a small community of Armenian Christians, of whom I had heard from my friend the Rev. G. Pigott, who had baptized two of their children when he visited Cabul in 1839, as Chaplain to the Bombay Army under Lord Keane. After some inquirey, we discovered them in a street in the Bala Hissar, leading from Jellalabad Gate; their buildings were on the North side of the street. We went up an alley and turned into a small court on the left, surrounded by buildings and filled with the implements of their trade. A little door led from this court into their church, a small dark building, but procuring lights, I found it was carpeted and kept clean, apparently with great care.", as cited on https://www.angelfire.com/hi/Azgaser/kabul.html

- ^ Hughes 1893, p. 456

- ^ Seth 1992, p. 209

- ^ Seth 1992, p. 210

- ^ Seth 1992, p. 217

- ^ Seth 1992, p. 218

- ^ [1] Archived 1 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Annie Basil, Armenian Settlements in India: from the earliest times to the present day, Calcutta, Armenian College, n.d., p.69

- ^ "Asia/Afghanistan – Barnabite Fathers 70 Years of Service in Afghanistan: Kabul Mission First Step for Growth of Local Church" Says Nuncio to Pakistan, Archbishop Alessandro D'Errico". Fides. 29 September 2003. Archived from the original on 11 June 2005. Retrieved 18 June 2006.

- ^ "A "public" church in Afghanistan? The past offers hope for the present (Overview)". Asianews.it. 12 October 2005. Retrieved 18 June 2006.

- ^ "Mass Celebrated Again in Afghan Capital". zenit.org. 27 January 2002. Archived from the original on 6 March 2002. Retrieved 11 August 2009.

- ^ "The Sisters of Mother Teresa arrive in Kabul". Asianews.it. 2 November 2004. Archived from the original on 12 January 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2006.

- ^ "Afghanistan May Now Be a Priestless Nation". zenit.org. 8 November 2001. Archived from the original on 3 December 2001. Retrieved 11 August 2009.

- ^ "Catholic presence expanding, Jesuit NGO and Sisters of Mother Teresa to arrive". Asianews.it. 23 May 2005. Archived from the original on 26 May 2005. Retrieved 18 June 2006.

- ^ "A "public" church in Afghanistan? The past offers hope for the present (Overview)". Asianews.it. 12 October 2005. Retrieved 18 June 2006.

- ^ "The Untold Story of Afghanistan". IAM. 26 July 2007. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ^ a b Floyd McClung (1 September 1996). Living on the Devil's Doorstep: From Kabul to Amsterdam. YWAM Publishing. pp. 67–. ISBN 978-0-927545-45-7. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ^ SPIEGEL, Matthias Gebauer, DER (30 March 2006). "Christians in Afghanistan: A Community of Faith and Fear - Der Spiegel - International". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ An Afghan Church Grows in Delhi. 22 July 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ Johnstone, Patrick; Miller, Duane Alexander (2015). "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census". IJRR. 11 (10): 1–19. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ Ahmed, Azam (21 June 2014). "A Christian Convert, on the Run in Afghanistan". The New York Times.

- ^ "Community Christians", After War, Is Faith Possible, The Lutterworth Press, pp. 178–185, 28 August 2008, doi:10.2307/j.ctt1cg4mhg.40, retrieved 17 July 2022

- ^ "Taliban Say No Christians Live in Afghanistan; US Groups Concerned". Voice of America. 16 May 2022.

- ^ a b http://www.shelter-now.org/about-shelter/our-work/ Archived 28 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine | accessdate=23 September 2010

- ^ http://www.aim.org/guest-column/murder-in-the-mountains/ Archived 18 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine | accessdate=23 September 2010

- ^ "Afghanistan: Eight foreign staff members of "Shelter Now International" receive visits of delegates of the International Committee of the Red Cross". www.icrc.org. Archived from the original on 29 October 2006. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ^ USCIRF Freedom of Religion report 2005 page 122

- ^ "Top Taleban commander 'arrested'". news.bbc.co.uk. 19 May 2006. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ^ USCIRF Freedom of Religion report 2009 page 144

- ^ "Extraordinary Missions present at the Solemn Funeral of Pope John Paul II". Vatican.va. Archived from the original on 19 February 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ^ "Afghan clerics want convert sent back". Al Jazeera. 4 April 2006. Archived from the original on 8 March 2020.

- ^ Afghan clerics call for Christian convert to be killed despite Western outrage, AP Archive, 23 March 2006

- ^ "Afghan Christian Convert Finds Sanctuary". NBC News. Associated Press. 29 March 2006. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ Constable, Pamela (23 March 2006). "For Afghans, Allies, A Clash Of Values". The Washington Post. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Munadi, Sultan M. (26 March 2006). "Afghan Case Against Christian Convert Falters". The New York Times.

- ^ "Monday, March 27". CNN. 28 March 2006.

- ^ Vinci, Alessio (29 March 2006). "Afghan convert arrives in Italy for asylum". CNN.

- ^ "Korean Missionaries under Fire". Time. 27 July 2007. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 8 September 2007.

- ^ Shah, Amir (29 April 2007). "Taliban to free 19 S. Korean hostages". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 9 September 2007. Retrieved 29 August 2007.

- ^ USCIRF Freedom of Religion report 2009 page 145

- ^ UK charity worker killed in Kabul, BBC News, 20 October 2008

- ^ "US burns Bibles in Afghanistan row". Al Jazeera. 22 May 2009. Archived from the original on 26 May 2009.

- ^

"Military burns unsolicited Bibles sent to Afghanistan". CNN. 22 May 2009. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

'This was irresponsible and dangerous journalism sensationalizing year-old footage of a religious service for U.S. soldiers on a U.S. base and inferring that troops are evangelizing to Afghans,' Col. Gregory Julian said.

- ^ "U.S. Military Accused of Handing Out Bibles in Afghanistan". Fox News. 4 May 2009. Archived from the original on 9 May 2009. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ^

"Bad Faith Efforts at Bagram". The Forward. 6 May 2009. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

These special forces guys — they hunt men basically", "We do the same things as Christians, we hunt people for Jesus. We do, we hunt them down.

- ^ a b USCIRF Freedom of Religion report 2010

- ^ Nordland, Rod; Wafa, Abdul Waheed (31 May 2010). "Afghanistan Suspends Two Aid Groups". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ^ "Afghans Protest Christian Aid Groups". cbn.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ^ http://www.rawa.org/temp/runews/2010/06/05/afghan-lawmaker-calls-for-execution-of-christian-converts-from-islam.html retrieved 23 September 2010 | quote=Those Afghans that appeared in this video film should be executed in public, the house should order the attorney general and the NDS (intelligence agency) to arrest these Afghans and execute them. | publisher=RAWA | accessdate=23 September 2010

- ^ http://www.nationalreview.com/corner/260050/america-quiet-execution-afghan-christian-said-musa-paul-marshall# retrieved 26 May 2012| quote=There are reports that Said Musa, whose situation I described at Christmas, will soon be executed for the 'crime' of choosing to become a Christian. Musa was one of about 25 Christians arrested on May 31, 2010, after a May 27 Noorin TV program showed video of a worship service held by indigenous Afghan Christians; he was arrested as he attempted to seek asylum at the German embassy. He converted to Christianity eight years ago, is the father of six young children, had a leg amputated after he stepped on a landmine while serving in the Afghan Army, and now has a prosthetic leg. His oldest child is eight and one is disabled (she cannot speak). He worked for the Red Cross/Red Crescent as an adviser to other amputees. | work=National Review | accessdate=26 May 2012

- ^ Matiullah Mati (21 November 2010). "Afghan Christian faces trial for alleged conversion from Islam". CNN. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ Gannon, Kathy (8 August 2010). "British aid worker killed in massacre in Afghanistan". The Herald. Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- ^ a b Nordland, Rod (7 August 2010). "10 Medical Aid Workers Are Found Slain in Afghanistan". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- ^ Gannon, Kathy (7 August 2010). "Afghan medical mission ends in death for 10". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 22 August 2010. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- ^ "Killing of British doctor in Afghanistan 'a cowardly act' says William Hague". The Daily Telegraph. London. 8 August 2010.

- ^ "Foreign medical workers among 10 killed in Afghanistan". BBC News. 7 August 2010.

- ^ "Eight foreign medical workers killed in Afghanistan". Reuters. 7 August 2010. Archived from the original on 21 August 2010.

- ^ The Afghanistan Analysts Network: Ten Dead in Badakhshan 6: Local Taliban Say it was Murder Archived 6 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Motlagh, Jason (9 August 2010). "Will Aid Workers' Killings End Civilian Surge?". Time. Archived from the original on 4 February 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- ^ Partlow, Joshua (8 August 2010). "Taliban kills 10 medical aid workers in northern Afghanistan". The Washington Post. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- ^ King, Laura (7 August 2010). "6 Americans among 10 charity workers killed in Taliban ambush". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- ^ Jonsson, Patrik (7 August 2010). "International Assistance Mission slayings: part of Taliban war strategy". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- ^ "Afghanistan war: Deadly ambush of medical mission roils one of safest provinces". The Christian Science Monitor. 7 August 2010. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ^ "Afghanistan aid workers' deaths highlights delicate position of Christian-affiliated groups". The Christian Science Monitor. 9 August 2010. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ^ Ray Rivera (5 February 2011). "Afghan Rights Fall Short for Christian Converts". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ "Afghan Christian Released from Prison and Safely out of the Country". Persecution.org. 20 April 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ Adam Schreck; Heidi Vogt (25 February 2011). "Afghan Case Against Christian Convert Falters". Washington Post. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ US State Dept 2021 report

- ^ Freedom House, Retrieved 2023-04-25

- ^ Christian Solidarity Worldwide, March 2023 report

Sources

[edit]- Hughes, Thomas P. (1893), "Twenty Years on the Afghan Frontier", The New York Independent, 45: 455–456, retrieved 26 July 2009

- Seth, Mesrovb Jacob (1992), "Chapter XVI: Armenians at Kabul – A Christian colony in Afghanistan", Armenians in India, from the earliest times to the present day: a work of original research, Asian Educational Services, pp. 207–224, ISBN 978-81-206-0812-2

External links

[edit]- Bible in Dari

- New Testament in Pashto Archived 25 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Watandar