Italian ironclad Affondatore

Affondatore after her final reconstruction

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Preceded by | Roma class |

| Succeeded by | Principe Amedeo class |

| History | |

| Name | Affondatore |

| Namesake | "Affondatore" is Italian for "Sinker" |

| Ordered | 11 October 1862 |

| Builder | Harrison, Millwall, London, United Kingdom |

| Laid down | 11 April 1863 |

| Launched | 3 November 1865 |

| Completed | Entered service in incomplete state 20 June 1866 |

| Stricken | 11 October 1907 |

| Fate | Unknown |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Ironclad ram |

| Displacement | |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 12.20 m (40 ft) |

| Draught | 6.35 m (20 ft 10 in) |

| Installed power | |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Range | 1,647 nautical miles (3,050 km; 1,895 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 309 |

| Armament |

|

| Armour | |

Affondatore was an armoured ram of the Regia Marina (Italian Royal Navy), built in the 1860s by Harrison, Millwall, London. Construction commenced in 1863; the ship, despite being incomplete, was brought to Italy during the Third Italian War of Independence. Affondatore, which translates as "Sinker", was initially designed to rely on her ram as her only weapon, but during construction she was also equipped with two 300-pounder guns.

The ship arrived off the island of Lissa shortly before the eponymous battle in July 1866. There, she served as the flagship of Admiral Carlo Pellion di Persano. During the action, she was involved in a melee with Austrian warships and was hit many times by Austrian guns. She sank in a storm in August, potentially as a result of the damage she incurred at Lissa, but was refloated and rebuilt between 1867 and 1873. She thereafter served with the main Italian fleet. She served as a guard ship in Venice from 1904 to 1907, and then as a depot ship in Taranto. The ultimate fate of the ship is unknown.

Design

[edit]On 11 October 1862, early in the Austro-Italian ironclad arms race, the Italian Navy placed an order with the British shipyard Mare of Millwall, London, for an armoured steam ram, to a design by the Italian naval officer Simone Antonio Saint-Bon, but financial problems resulted in the order being transferred to the shipyard Harrison, also of Millwall. Saint-Bon had originally intended the ship to be unarmed, relying only on its ram to sink enemy ships, but an engineer at Harrison revised the plan to include two large-caliber guns.[1][2]

General characteristics and machinery

[edit]

Affondatore had a length of 89.56 metres (293 ft 10 in) between perpendiculars and 93.8 m (307 ft 9 in) overall, with a beam of 12.20 m (40 ft) and a draught of 6.35 m (20 ft 10 in). She displaced 4,006 long tons (4,070 t) normally and up to 4,307 long tons (4,376 t) at full load. As built, the ship had a very minimal superstructure, with only a small conning tower. She had a crew of 309 officers and enlisted, which later increased to 356.[3]

The ship was powered by one single-expansion steam engine that drove a single propeller shaft. Steam was provided by eight rectangular boilers, which were trunked into two funnels placed amidships. The engines generated 2,717 indicated horsepower (2,026 kW), giving a top speed of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph). Sufficient coal was carried to give a range of 1,647 nautical miles (3,050 km; 1,895 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). To supplement the steam engine on long-range voyages, Affondatore was fitted with a two-masted schooner rig.[2][3]

Armament and armour

[edit]As built, Affondatore carried a main gun armament of two 300-pounder Armstrong guns in single turrets fore and aft. The exact diameter of the guns is unknown, but they were either 220 mm (8.7 in)[2] or 228 mm (9 in).[3] She also carried two 80 mm (3.1 in) guns to be used in landings. A 2.5-metre-long (8.2 ft) ram was fitted. The ship had an iron hull, with sides and turrets protected by 127 mm (5 in) of wrought iron armour, with a 50-millimetre-thick (2 in) armoured deck.[2][4]

Service history

[edit]Affondatore was laid down on 11 April 1863 and launched on 3 November 1865.[3] With Italy preparing to declare war against Austria in June 1866, the Italian government ordered Affondatore's crew to move the incomplete ship from British waters to Cherbourg for fitting out, in order to avoid the possibility of the ship being confiscated by the British. Affondatore left Cherbourg on 20 June, the day Italy declared war, sailing to join the main Italian fleet which was operating in the Adriatic Sea.[5] The Third Italian War of Independence was fought concurrently with the Austro-Prussian War.[6] The Italian fleet commander, Admiral Carlo Pellion di Persano, initially adopted a cautious course of action; he was unwilling to risk battle with the Austrian Navy, despite the fact that the Austrian fleet was much weaker than his own. Persano claimed he was simply waiting for Affondatore to arrive, but his inaction weakened morale in the fleet, with many of his subordinates openly accusing him of cowardice. The ship passed through Gibraltar on 28 June, making her way into the Mediterranean.[7]

Battle of Lissa

[edit]

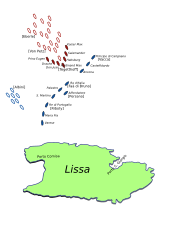

On 16 July, Persano took the Italian fleet out of Ancona, bound for Lissa, where they arrived on the 18th. With them, they brought troop transports carrying 3,000 soldiers; the Italian warships began bombarding the Austrian forts on the island, with the intention of landing the soldiers once the fortresses had been silenced. In response, the Austrian Navy sent the fleet under Rear Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff to attack the Italian ships. After arriving off Lissa on the 18th,[8] Persano spent two days unsuccessfully trying to suppress the Austrian gun batteries on the island so he could land the soldiers. This resulted in a significant expenditure of ammunition, which would affect the outcome of the coming battle.[9] Affondatore joined the fleet after it had arrived off Lissa on 19 July,[10] but her crew were not fully worked up and had struggled to handle the ship while sailing to Italy and the Adriatic.[11][12] Persano decided to make a third attempt to force a landing on the 20th, but before the Italians could begin the attack, the dispatch boat Esploratore arrived, bringing news of Tegetthoff's approach. Persano's fleet was in disarray; the three ships of Admiral Giovanni Vacca's 1st Division were three miles to the northeast from Persano's main force, and three other ironclads were further away to the west.[13]

Persano immediately ordered his ships to form up with Vacca's, first in line abreast formation, and then in line ahead formation; Affondatore was initially located on the disengaged side of the Italian line. Shortly before the action began, Persano decided to leave his flagship, Re d'Italia, and transfer to Affondatore, though none of his subordinates on the other ships were aware of the change. Persano used Affondatore to steam up and down the Italian line, issuing various orders to the individual ships, but as the ship captains were not aware that he was aboard Affondatore, they ignored his signals. The Italians were thus left to fight as individuals without direction. More dangerously, by stopping Re d'Italia, he allowed a significant gap to open up between Vacca's three ships and the rest of the fleet. Tegetthoff took his fleet through the gap between Vacca's and Persano's ships, though he failed to ram any Italian vessels on the first pass. The Austrians then turned back toward Persano's ships, and took the leading ships under heavy fire. Persano initially kept his ship out of the action, until after Re d'Italia had been rammed and sunk by the Austrian flagship, Erzherzog Ferdinand Max.[14]

After the Austrians began targeting the ironclad Re di Portogallo, Persano decided to finally commit his ship to the battle, by attempting to ram the Austrian wooden ship-of-the-line Kaiser, though he failed to make a direct strike. Kaiser then rammed Re di Portogallo, before Affondatore made a second, unsuccessful attempt to ram her. Affondatore did, however, score a hit with one of her guns, badly damaging Kaiser, killing or wounding twenty of her crew. By this time, the Austrian ironclads disengaged from the melee to protect their wooden ships. Persano made an attempt to follow them with Affondatore, but he broke off the attempt when only one of his other ironclads followed him. His crews were badly demoralized by the battle, and his ships were low on ammunition and coal. The Italian fleet began to withdraw, followed by the Austrians; as night began to fall, the opposing fleets disengaged completely, heading for Ancona and Pola, respectively.[15] In the course of the battle, she had been hit by 22 Austrian shells.[2]

Later career

[edit]

Affondatore sank in a storm in Ancona harbour on 6 August 1866,[2] which may have been due to damage received during the Battle of Lissa.[16] According to naval historians Greene and Massignani, however, Affondatore merely took on too much water due to her low freeboard; the damage sustained at Lissa had nothing to do with her sinking.[17] The contemporary French journal La Revue Maritime et Coloniale instead states that it was faulty installation of the ship's hatches that allowed water to enter the ship in bad weather.[18] She had been refloated by 5 November.[19] After refloating, Affondatore was rebuilt at La Spezia from 1867 to 1873. The ship's masts and sails were removed, with a single mast carrying a fighting top fitted in their place.[2] In 1883–1885, she was fitted with new boilers and engines, rated at 3,240 indicated horsepower (2,420 kW),[2] and giving a speed of 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph).[20] During the annual fleet maneuvers held in 1885, Affondatore served in the 2nd Division of the "Western Squadron"; she was joined by the ironclad Roma and five torpedo boats. The "Western Squadron" attacked the defending "Eastern Squadron", simulating a Franco-Italian conflict, with operations conducted off Sardinia.[21]

Affondatore was present during a naval review held for the German Kaiser Wilhelm II during a visit to Italy in 1888.[22] From 1888 to 1889, Affondatore was significantly modernized. Her main battery guns were replaced with two 254 mm (10 in) guns in new turrets. A new, larger superstructure was built to house a new secondary armament, and a second military mast was fitted. Her new secondary battery consisted of six 119 mm (4.7 in) guns in single mounts, one 75 mm (3 in) QF gun, eight 57 mm (2.2 in) QF guns, and four 37 mm (1.5 in) Hotchkiss revolver cannon. In 1891, Affondatore became a torpedo training ship, and was fitted with two torpedo tubes.[2][23]

The ship served in the 3rd Division of the Active Squadron during the 1893 fleet maneuvers, along with the ironclad Enrico Dandolo, the torpedo cruiser Goito, and four torpedo boats. During the maneuvers, which lasted from 6 August to 5 September, the ships of the Active Squadron simulated a French attack on the Italian fleet.[24] As of 1 October that year, she was stationed in Taranto along with the ironclad Ancona, the protected cruisers Liguria, Etruria, and Umbria, the torpedo cruisers Monzambano, Montebello, and Confienza, and several other vessels. She remained there through 1894.[25] By 1899, Affondatore was in service with the 2nd Division, which also included the ironclads Sicilia and Castelfidardo, and the torpedo cruisers Partenope and Urania.[26] In 1904, she was assigned to the defence of Venice, serving as a guard ship until 1907. She was stricken on 11 October 1907, and thereafter served as a floating ammunition depot at Taranto. Her ultimate fate is unknown.[2][23]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Fraccaroli, pp. 335, 339.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Ordovini, Petronio, & Sullivan, p. 354.

- ^ a b c d Fraccaroli, p. 339.

- ^ Fraccaroli, pp. 339–340.

- ^ Fraccaroli, pp. 335, 339–340.

- ^ Sondhaus, p. 1.

- ^ Greene & Massignani, pp. 217–222.

- ^ Sondhaus, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 219–224.

- ^ "La Battaglia di Lissa".

- ^ Fraccaroli, p. 335.

- ^ "The Battle of Lissa", p. 417.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 223–225.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 232–238.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 238–241, 250.

- ^ Wilson, p. 245.

- ^ Greene & Massignani, p. 237.

- ^ Dupont, p. 425.

- ^ Miscellaneous.

- ^ Brassey 1888, p. 354.

- ^ Brassey 1886, p. 141.

- ^ Brassey 1889, p. 453.

- ^ a b Fraccaroli, p. 340.

- ^ Clarke & Thursfield, pp. 202–203.

- ^ Garbett 1894, p. 201.

- ^ Brassey 1899, p. 72.

References

[edit]- Brassey, Thomas, ed. (1886). "Evolutions of the Italian Navy, 1885". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co. OCLC 896741963.

- Brassey, Thomas, ed. (1888). "Notes on Italian Navy, armoured ships—Italia and Lepanto—Sicilia, Re Umberto, and Sardegna—Andrea Doria class". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co. OCLC 896741963.

- Brassey, Thomas, ed. (1889). "Foreign Naval Manoevres". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co. pp. 450–455. OCLC 5973345.

- Brassey, Thomas, ed. (1899). "Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co. OCLC 896741963.

- Clarke, George S. & Thursfield, James R. (1897). The Navy and the Nation. London: John Murray.

- Dupont, Paul, ed. (1872). "Notes sur La Marine Et Les Ports Militaires de L'Italie" [Notes on the Navy and Military Ports of Italy]. La Revue Maritime et Coloniale [The Naval and Colonial Review] (in French). XXXII. Paris: Imprimerie Administrative de Paul Dupont: 415–430.

- Fraccaroli, Aldo (1979). "Italy". In Gardiner, Robert (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 334–359. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Garbett, H., ed. (1894). "Naval and Military Notes". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. XXXVIII. London: J. J. Keliher: 193–206. OCLC 8007941.

- Greene, Jack; Massignani, Alessandro (1998). Ironclads at War: The Origin and Development of the Armored Warship, 1854–1891. Pennsylvania: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-938289-58-6.

- "La Battaglia di Lissa (20 luglio 1866)" [The Battle of Lissa (20 July 1866)] (in Italian). Marina Militare. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- "Miscellaneous". Birmingham Daily Post. No. 2582. Birmingham. 5 November 1866.

- Ordovini, Aldo F.; Petronio, Fulvio & Sullivan, David M. (December 2014). "Capital Ships of the Royal Italian Navy, 1860–1918: Part I: The Formidabile, Principe di Carignano, Re d'Italia, Regina Maria Pia, Affondatore, Roma and Principe Amedeo Classes". Warship International. Vol. 51, no. 4. pp. 323–360. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-034-9.

- "The Battle of Lissa" (PDF). The Engineer. Vol. 22. 30 November 1866. pp. 417–418. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2015.

- Wilson, Herbert Wrigley (1896). Ironclads in Action: A Sketch of Naval Warfare from 1855 to 1895. London: S. Low, Marston and Company. OCLC 1111061.

External links

[edit]- Affondatore Marina Militare website (in Italian)