Adverse childhood experiences

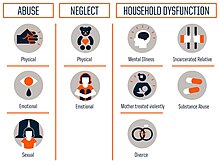

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) include childhood emotional, physical, or sexual abuse and household dysfunction during childhood. The categories are verbal abuse, physical abuse, contact sexual abuse, a battered mother/father, household substance abuse, household mental illness, incarcerated household members, and parental separation or divorce. The experiences chosen were based upon prior research that has shown to them to have significant negative health or social implications, and for which substantial efforts are being made in the public and private sector to reduce their frequency of occurrence.[1] Scientific evidence is mounting that such adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) have a profound long-term effect on health. Research shows that exposure to abuse and to serious forms of family dysfunction in the childhood family environment are likely to activate the stress response, thus potentially disrupting the developing nervous, immune, and metabolic systems of children.[2][3][4] ACEs are associated with lifelong physical and mental health problems that emerge in adolescence and persist into adulthood,[5] including cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, autoimmune diseases, substance abuse, and depression.[6][7][8]

Definition and types

[edit]The concept of adverse childhood experiences refers to various traumatic events or circumstances affecting children before the age of 18 and causing mental or physical harm.[9] There are 10 types of ACEs:

- Physical abuse: Any intentional act that causes physical harm through bodily contact.

- Sexual abuse: Any forceful, unwanted, or otherwise abusive sexual behavior.

- Psychological abuse: Any intentional act that causes psychological harm, such as gaslighting, bullying, or guilt-tripping.

- Physical neglect: Failure to help meet the basic biological needs of a child, such as food, water, and shelter.

- Psychological neglect: Failure to help meet the basic emotional needs of a child, such as attention and affection.

- Witnessing domestic abuse: Observing violence occurring between individuals in a domestic setting, such as between parents or other family members.

- Witnessing drug or alcohol abuse: Having a close family member who misused drugs or alcohol.

- Mental health problems: Having a close family member or otherwise important individual experience mental health problems.

- Imprisonment: Having a close family member or otherwise important individual serve time in prison.

- Parental separation or divorce: Parents or guardians separating or divorcing on account of a relationship breakdown.[9]

The different adverse childhood experiences are not isolated and in many cases multiple ACEs impact someone at the same time.

Prevalence

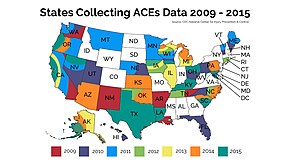

[edit]Adverse childhood experiences are common across all parts of societies, in 2009 the CDC started collecting data on the prevalence of ACEs as part of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS).[10] In the first year data was collected across five US states and included over 24,000 people. The prevalence of each ACE ranged from a high of 29.1% for household substance abuse to a low of having an incarcerated family member (7.2%). Approximately one quarter (25.9%) of respondents reported verbal abuse, 14.8% reported physical abuse, and 12.2% reported sexual abuse. For ACEs measuring family dysfunction, 26.6% reported separated or divorced parents; 19.4% reported that they had lived with someone who was depressed, mentally ill, or suicidal; and 16.3% reported witnessing domestic violence. Men and women reported similar prevalences for each ACE, with the exception of sexual abuse (17.2% for women and 6.7% for men), living with a mentally ill household member (22.0% for women and 16.7% for men), and living with a substance-abusing family member (30.6% for women and 27.5% for men). Younger respondents more often reported living with an incarcerated and/or mentally ill household member. For each ACE, a sharp decrease was observed in prevalence reported by adults aged ≥55 years. For example, the prevalence of reported physical abuse was 16.9% among adults aged 18--24 years compared with 9.6% among those aged ≥55 years.[11]

Non-Hispanic black respondents reported the lowest prevalence of each ACE category among all racial/ethnic groups, with the exception of having had an incarcerated family member, parental separation or divorce, and witnessing domestic violence. Hispanics reported a higher prevalence than non-Hispanic whites of physical abuse, witnessing domestic violence, and having an incarcerated family member (p<0.05). Those respondents with less than a high school education compared with those with more than a high school education had a greater prevalence of physical abuse, an incarcerated family member, substance abuse, and separation/divorce. Among the five states, little variation was observed.

Approximately 41% of respondents reported having no ACEs, 22% reported one ACE, and 8.7% reported five or more ACEs. Men (6.9%) were less likely to report five or more ACEs compared with women (10.3%). Respondents aged ≥55 years reported the fewest ACEs, but the younger age groups did not differ from one another. Non-Hispanic blacks were less likely to report five or more ACEs (4.9%) compared with non-Hispanic whites (8.9%), Hispanics (9.1%), and other non-Hispanics (11.7%). However, non-Hispanic black respondents were not significantly more likely to report zero ACEs compared with other racial/ethnic groups. Respondents with the lowest educational attainment were significantly more likely to report five or more ACEs compared with those with higher education levels (14.9% versus 8.7% among high school graduates and 7.7% in those with more than a high school education). Overall, little state-by-state variation was observed in the number of ACEs reported by each respondent.[11][12][13]

There are no reliable global estimates for the prevalence of child maltreatment. Data for many countries, especially low- and middle-income countries, are lacking. Current estimates vary widely depending on the country and the method of research used. Approximately 20% of women and 5–10% of men report being sexually abused as children, while 25–50% of all children report being physically abused.[14][15]

Health outcomes due to ACEs

[edit]Childhood

[edit]With one in four children experiencing or witnessing a potentially traumatic event, the relationship between ACEs and poor health outcomes has been established for years.[16][17] With multiple adverse childhood experiences being equal to various stresses, and adversity.[clarification needed][18] Children who grow up in an unsafe environment are at risk for developing adverse health outcomes, affecting brain development, immune systems, and regulatory systems.[19][20][21] Adverse childhood experiences can alter the structural development of neural networks and the biochemistry of neuroendocrine systems[22][23][24][25] and may have long-term effects on the body, including speeding up the processes of disease and aging and compromising immune systems.[26][27][28] Further research on ACEs determined that children who experience ACEs are more likely than their similar-aged peers to experience challenges in their biological, emotional, social, and cognitive functioning.[29] Also, children who have experienced an ACE are at higher risk of being re-traumatized or suffering multiple ACEs.[30] The amount and types of ACEs can cause significant negative impacts and increase the risk of internalizing and externalizing in children.[31] Additionally behavioral challenges can arise in children who have been exposed to ACEs including juvenile recidivism,[32] reduced resiliency,[33] and lower academic performance.[34][35]

Adulthood

[edit]Adults with ACE exposure report having worse mental and physical health, more serious symptoms related to illnesses, and poorer life outcomes.[36][37] Across numerous studies these effects go beyond behavioral and medical issues, and include damage to DNA,[37] higher levels of stress hormones,[38] and reduced immune function.[39] The effects of ACEs goes beyond just physical and behavioral health with studies reporting that people with high ACEs scores showed less trust in government COVID-19 information and policies.[40]

Biological changes

[edit]Due to many of the early life stressors caused by exposure to ACEs there are noted changes the body in people with ACE exposures compared to people with little to no ACE exposure.[41] This is most evident in structural changes in the brain with the hippocampus,[42][43] the amygdala,[44] and the corpus callosum[42] being important targets of study.[45] These areas of the brain are more vulnerable than others due to the higher density of glucocorticoid receptors in these regions of the brain.[46][47] Multiple effects have been noted including diminished thickness,[48] reduced size,[49] and reduced size of connective networks in the brain.[50]

Physical health

[edit]ACEs have been linked to numerous negative health and lifestyle issues into adulthood across multiple countries and regions including the United States,[51] the European Union,[52] South Africa,[53] and Asia.[54] Across all these groups researchers have reported seeing the adoption of higher rates of unhealthy lifestyle behavior including sexual risk taking,[55] smoking,[56] heavy drinking,[57] and obesity.[58][59] The associations between these lifestyle issues and ACEs shows a dose response relationship with people having four or more ACEs have significantly more of these lifestyle problems.[60][61] Physical health problems arise in people with ACEs with a similar dose response relationship.[55] Chronic illnesses such as asthma,[62] arthritis,[55] cardiovascular disease,[63] cancer,[64] diabetes,[65] stroke,[66] and migraines[67] show increased symptom severity in step with exposure to ACEs.[55]

Mental health

[edit]Mental health issues have been well known in the face of childhood trauma and exposure to ACEs is no different. According to a large study conducted in 21 countries nearly one in three mental health conditions in adulthood are directly related to an adverse childhood experience.[68]

A study of high school students in Chicago [69] showed significantly elevated levels of school problems, hyperactivity, and lower levels of personal adjustment as number of ACEs increased.

Multiple mental health conditions found to have a dose response relationship with symptom severity and prevalence including depression,[70][71] attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder,[72] anxiety[73][74] suicidality,[75] bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.[76] Depressive symptoms in adulthood showed one of the strongest dose response relationships with ACEs, with an ACE score of one increasing the risk of depressive symptoms by 50% and an ACE score of four or more showing a fourfold increase.[77] Later research also demonstrated that ACE scores are related to increased rates and severity of psychiatric and mental disorders, as well as higher rates of prescription psychotropic medication use.[22]

Special populations

[edit]Additionally, epigenetic transmission may occur due to stress during pregnancy or during interactions between mother and newborns. Maternal stress, depression, and exposure to partner violence have all been shown to have epigenetic effects on infants.[25][78] Additionally, mothers who experienced ACEs are more likely than those who did not have ACEs to engage in illicit drug use during pregnancy, particlarly if the ACEs experienced were related to high maltreatment or emotional abuse. In cases where mothers experienced emotional or physical abuse as well as intra-familial violence exposure are more likely to give birth to lighter-weight babies than those who did not have those childhood experiences.[79]

Implementing practices

[edit]Globally knowledge about the prevalence and consequences of adverse childhood experiences has shifted policy makers and mental health practitioners towards increasing, trauma-informed and resilience-building practices.[80][81][82] This work has been over 20 years in the making bringing together research are implemented in communities, education settings,[83] public health departments, social services, faith-based organizations and criminal justice.[84][85]

Communities

[edit]As knowledge about the prevalence and consequences of ACEs increases, more communities seek to integrate trauma-informed and resilience-building practices into their agencies and systems.[86]

Indigenous populations show similar patterns of mental and physical health challenges as other minority groups.[87] Interventions have been developed in American Indian tribal communities and have demonstrated that social support and cultural involvement can ameliorate the negative physical health effects of ACEs.[88]

There is a paucity of empirical research documenting the experiences of communities who have attempted to implement information about ACEs and trauma-informed practice into widespread public action. A study on Pottstown, Pennsylvania's process demonstrated the challenges associated with community implementation. The Pottstown Trauma-Informed Community Connection (PTICC) initiative evolved from a series of prior collectives that all had similar goals of creating community resilience in order to prevent and treat ACEs. Over the course of the two-year study, over 230 individuals from nearly 100 organizations attended one training offered by the PTICC, raising the number of engaged public sectors from 2 to 14. Participation in training and events was fairly steady and this was largely due to community networking.[89]

However, the PTICC faced several challenges similar to those predicted by the Building Community Resilience model. These barriers included availability of resources over time, competition for power within the group, and the lack of systemic change needed to support long-term goals. Still, Pottstown has built a trauma-informed community foundation and offers lessons to other communities who have similar goals: start with a dedicated small team, identify community connectors, secure long-term financial backing, and conduct data-informed evaluations throughout.[89]

Other community examples exist, such as Tarpon Springs, Florida which became the first trauma-informed community in 2011.[90][91] Trauma-informed initiatives in Tarpon Springs include trauma-awareness training for the local housing authority, changes in programs for ex-offenders, and new approaches to educating students with learning difficulties.[92]

Education

[edit]

ACEs exposure is widespread globally, one study from the National Survey of Children's Health in the United States reported that approximately 68% of children 0–17 years old had experienced one or more ACEs.[93] The impact of ACEs on children can manifest in difficulties focusing, self regulating, trusting others, and can lead to negative cognitive effects. One study found that a child with 4 or more ACEs was 32 times more likely to be labeled with a behavioral or cognitive problem than a child with no ACEs.[94] Another study found that students with at least three ACEs are three times as likely to experience academic failure, six times as likely to have behavioral problems, and five times as likely to have attendance problems.[95] The trauma-informed school movement aims to train teachers and staff to help children self-regulate, and to help families that are having problems that result in children's normal response to trauma. It also seeks to provide behavioral consequences that will not re-traumatize a child.[96]

Trauma-informed education refers to the specific use of knowledge about trauma and its expression to modify support for children to improve their developmental success.[97] The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) describes a trauma-informed school system as a place where school community members work to provide trauma awareness, knowledge and skills to respond to potentially negative outcomes following traumatic stress.[98] The NCTSN published a study that discussed the Attachment, Self-Regulation, and Competency (ARC) model, which other researchers have based their subsequent studies of trauma-informed education practices off of.[94][99] Trauma-sensitive or trauma-informed schooling has become increasingly popular in Washington, Massachusetts, and California in the last 10 years.[93]

In their 2002 survey, the AAUW reported that, of students who had been harassed, 38% were harassed by teachers or other school employees. One survey that was conducted with psychology students reports that 10% had sexual interactions with their educators; in turn, 13% of educators reported sexual interaction with their students.[100] In a national survey conducted for the American Association of University Women Educational Foundation in 2000, it was found that roughly 290,000 students experienced some sort of physical sexual abuse by a public school employee between 1991 and 2000. A major 2004 study commissioned by the U.S. Department of Education found that nearly 10 percent of U.S. public school students reported having been targeted with sexual attention by school employees. Charol Shakeshaft, a researcher in the field, claimed that sexual abuse in public schools "is likely more than 100 times the abuse by priests."[101]

Literacy

[edit]ACEs in childhood and adolescence can affect literacy development in many ways. Children who have faced trauma encounter more learning challenges in school and higher levels of stress internally.[102] Building literacy skills can be negatively impacted both by the lack of literacy experiences in the home, missing parts of early-childhood education, and by actually altering brain development. There are techniques that can be employed by educators and clinicians to try and remediate the effects of the adverse experiences and move children forward in their literacy and educational development.[103]

ACEs affect parts of the brain that involve memory, executive functioning, and attention.[104] The parts of the brain and hormones that register fear and stress are in overdrive, whereas the prefrontal cortex, which regulates executive functions, is compromised. This impacts impulse control, focus, and critical thinking.[105] Memory is also a struggle as there is less capacity to process new input.[102] The stress of ACEs creates a state of "fight, flight, or freeze" which leaves children unavailable for learning.[102] The ability to process new information or collaborate with peers in school is eclipsed by the brain's necessity to survive the stress experienced in their environment outside of school.[104] The inconsistency and instability of the home environment alters the many cognitive processes necessary for effective literacy acquisition.

Young people who are refugees experience trauma whether they were part of the immigration process or were born in the country (where they currently attend school) where the family settled[citation needed]. During this resettlement phase[106] many of the second-generation refugee child's problems come to light. The disruption in education and instability in the home, as a result of the family's journey, can lead to gaps in exposures to literacy in the home [citation needed]. Literacy experiences outside of school include parents reading with kids and borrowing or buying books for the home.[105] Early-childhood literacy education includes explicit teaching of reading and writing skills, building phonological awareness, and academic vocabulary.[105] Resettlement affects children's phonemic awareness and exposure to academic vocabulary since many families are unable to fully provide these out of school experiences.[106] If the child was non-English speaking, then they are acquiring English as a new language. There already exists an achievement gap between native-English speakers in the United States and students who are learning English as their second (or third or fourth) language.[106]

The resulting literacy issues from trauma, reflected in low reading scores, puts children with ACEs at-risk for grade retention. As students, they are almost twice as likely to leave high school without graduating.[107] While there are many years from when a young child starts kindergarten and an adolescent enters high school, there is a link between weak emergent literacy leading to eventually dropping out of high school.[107] It is crucial to intervene as early as possible.

Trauma-informed educators and clinicians can help remediate both young children and adolescents in school. With a knowledge and sensitivity of ACEs and their effects, proper and effective interventions can be implemented.[108] This can also begin to create a stable environment in which children can learn and create stable attachments.[105] Physical movement in the form of "brain energizers" can help regulate children's brains and alleviate stress when done 1–2 times during the school day. In one study, both behavior and literacy skills were assessed to see how effective the physical movement, or "brain energizers" were.[102] Literacy scores for a classroom that used the brain energizers (which ranged from movement activities found online to other movement activities selected by the teacher and students), improved by 117% from beginning to end of year.[102] In a school setting, the person who has experienced trauma and the person who is in the moment with the person trying to talk or write about it can connect, even when language fails to adequately describe the depth and complexity of the emotions felt.[109] While there is an inherent discomfort in this, educators can embrace this discomfort and give children a space to express this, as best they can, in the classroom. Those who are able to develop more "resilience" might be able to function better in school, but this is dependent on the ratio of protective factors[104] compared to ACEs.

Social services

[edit]Social service providers—including welfare systems, housing authorities, homeless shelters, and domestic violence centers – are adopting trauma-informed approaches that help to prevent ACEs or minimize their impact. Utilizing tools that screen for trauma can help a social service worker direct their clients to interventions that meet their specific needs.[110] Trauma-informed practices can also help social service providers look at how trauma impacts the whole family.[111]

Trauma-informed approaches can improve child welfare services by openly discussing trauma and addressing parental trauma.[according to whom?][112] The New Hampshire Division for Children Youth and Families (DCYF) is taking a trauma-informed approach to their foster care services by educating staff about childhood trauma, screening children entering foster care for trauma, using trauma-informed language to mitigate further traumatization, mentoring birth parents and involving them in collaborative parenting, and training foster parents to be trauma-informed.[110]

Housing authorities are also becoming trauma-informed. Supportive housing can sometimes recreate control and power dynamics associated with clients' early trauma.[113] This can be reduced through trauma-informed practices, such as training staff to be respectful of clients' space by scheduling appointments and not letting themselves into clients' private spaces, and also understanding that an aggressive response may be trauma-related coping strategies.[113] Up to 50% of people with housing insecurity experienced at least four ACEs.[114]

A study in the UK looked at the views of young people exposed to ACEs on what support they needed from social services. The study grouped the findings into three categories: emotional support, practical support and service delivery. Emotional support included interacting with other young people for support and a sense solidarity, and supportive relationships with adults that are based on empathy, active listening and non-judgement. Practical support meant information about the available services, practical advice about everyday challenges and respite from these challenges through recreation. Young people expected service delivery to be continuous and dependable, and they needed flexibility and control over the support processes.[115][116] The needs of young people with ACEs were found not to match the types of support they are offered.[117]

Health care services

[edit]Screening for or talking about ACEs with parents and children can help to foster healthy physical and psychological development and can help doctors understand the circumstances that children and their parents are facing. By screening for ACEs in children, pediatric doctors and nurses can better understand behavioral problems. Some doctors have questioned whether some behaviors resulting in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnoses are in fact reactions to trauma. Children who have experienced four or more ACEs are three times as likely to take ADHD medication when compared with children with less than four ACEs.[118] Screening parents for their ACEs allows doctors to provide the appropriate support to parents who have experienced trauma, helping them to build resilience, foster attachment with their children, and prevent a family cycle of ACEs.[119][120]

For people whose adverse childhood experiences were of abuse or neglect cognitive behavioural therapy has been studied and shown to be effective.[121]

Public health

[edit]Objections to screening for ACEs include the lack of randomized controlled trials that show that such measures can be used to actually improve health outcomes, the scale collapses items and has limited item coverage, there are no standard protocols for how to use the information gathered, and that revisiting negative childhood experiences could be emotionally traumatic.[122][123] Other obstacles to adoption include that the technique is not taught in medical schools, is not billable, and the nature of the conversation makes some doctors personally uncomfortable.[122] Some public health centers see ACEs as an important way (especially for mothers and children)[124] to target health interventions for individuals during sensitive periods of development.

Resilience and resources

[edit]Resilience is the ability to adapt or cope in the face of significant adversity and threats such as health problems, stress experienced in the workplace or home.[125] Resiliency can mediate the relationship of the effects of ACEs and health problem in adulthood.[126][33] Being able use emotion regulation resources such as cognitive reappraisal and mindfulness people are able to protect themselves from the potential negative effects of stressors. These skills can be taught to people but people living with ACEs score lower on measures of resilience and emotion regulation.[33][127]

Resilience and access to other resources are protective factors against the effects of exposure to ACEs.[88][128][129] Increasing resilience in children can help provide a buffer for those who have been exposed to trauma and have a higher ACE score.[33] People and children who have fostered resiliency have the skills and abilities to embrace behaviors that can foster growth.[130] In childhood, resiliency and attachment security can be fostered from having a caring adult in a child's life.[131][132]

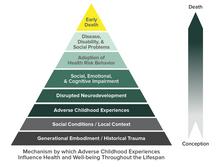

Adverse childhood experiences study

[edit]The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study was a collaborative effort between the US private healthcare organization Kaiser Permanente and the government-run Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to examine the long-term relationship between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and a variety of health behaviors and health outcomes in adulthood. An underlying thesis of the ACE Study is that stressful or traumatic childhood experiences have negative neurodevelopmental impacts that persist over the lifespan and increase the risk of a variety of health and social problems.[77][1]

The ACE Study was based at Kaiser Permanente's San Diego Health Appraisal Clinic, a primary care clinic where each year more than 50,000 adult members of the Kaiser Permanente Health Maintenance Organization receive an annual, standardized, biopsychosocial medical examination.[133] Each member who visits the Health Appraisal Clinic completes a standardized medical questionnaire.[77] The medical history is completed by a health care provider who also performs a general physical examination and reviews laboratory test results with the patient.[77] Appointments for most members are obtained by self-referral with 20% referred by their health care provider.[77] A review of Kaiser Permanente members aged 25 years or older in San Diego and continuously enrolled between 1992 and 1995 revealed that 81% of those members had been evaluated at the Health Appraisal Clinic.[77] All Kaiser members who completed medical examinations at the Health Appraisal Clinic between August and November of 1995, between January and March of 1996 (Wave I: 13,494 persons), and between April and October of 1997 (Wave II: 13,330 persons) were eligible to participate in the ACE Study.[134] Within two weeks after a member's visit to the Health Appraisal Clinic, a Study questionnaire was mailed asking questions about health behaviours and adverse childhood experiences. A total of 17,421 (68%) persons responded; 84 persons had incomplete information on race and educational attainment leaving 17,337 persons available in the baseline cohort.[134]

In the 1980s, the dropout rate of participants at Kaiser Permanente's obesity clinic in San Diego, California, was about 50%; despite all of the dropouts successfully losing weight under the program.[135] Vincent Felitti, head of Kaiser Permanente's Department of Preventive Medicine in San Diego, conducted interviews with people who had left the program, and discovered that a majority of 286 people he interviewed had experienced childhood sexual abuse. The interview findings suggested to Felitti that weight gain might be a coping mechanism for depression, anxiety, and fear.[135]

Felitti and Robert Anda from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) went on to survey childhood trauma experiences of over 17,000 Kaiser Permanente patient volunteers.[135] The 17,337 participants were volunteers from approximately 26,000 consecutive Kaiser Permanente members.[136] Participants were asked about different types of adverse childhood experiences that had been identified in earlier research literature: Physical abuse, Sexual abuse, Emotional abuse, Physical neglect, Emotional neglect, Exposure to domestic violence, Household substance abuse, Household mental illness, Parental separation or divorce, Incarcerated household member.[137]

![]() This article incorporates text from this source, which is by David W Brown, Robert F Anda, Vincent J Felitti, Valerie J Edwards, Ann Marie Malarcher, Janet B Croft, and Wayne H Giles available under the CC BY 2.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is by David W Brown, Robert F Anda, Vincent J Felitti, Valerie J Edwards, Ann Marie Malarcher, Janet B Croft, and Wayne H Giles available under the CC BY 2.0 license.

Findings

[edit]

According to the United States' Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the ACE study found that:

- Adverse childhood experiences are common. For example, 28% of study participants reported physical abuse and 21% reported sexual abuse. Many also reported experiencing a divorce or parental separation, or having a parent with a mental and/or substance use disorder.[142]

- Adverse childhood experiences often occur together. Almost 40% of the original sample reported two or more ACEs and 12.5% experienced four or more. Because ACEs occur in clusters, many subsequent studies have examined the cumulative effects of ACEs rather than the individual effects of each.[142]

- Adverse childhood experiences have a dose–response relationship with many health problems. As researchers followed participants over time, they discovered that a person's cumulative ACEs score has a strong, graded relationship to numerous health, social, and behavioral problems throughout their lifespan, including substance use disorders. Furthermore, many problems related to ACEs tend to be comorbid, or co-occurring.[142]

About two-thirds of individuals reported at least one adverse childhood experience; 87% of individuals who reported one ACE reported at least one additional ACE.[137] The number of ACEs was strongly associated with adulthood high-risk health behaviors such as smoking, alcohol and drug abuse, promiscuity, and severe obesity,[59] and correlated with ill-health including depression,[143] heart disease, cancer,[64] chronic lung disease and shortened lifespan.[137][77] [144] Compared to an ACE score of zero, having four adverse childhood experiences was associated with a seven-fold (700%) increase in alcoholism, a doubling of risk of being diagnosed with cancer, and a four-fold increase in emphysema; an ACE score above six was associated with a 30-fold (3000%) increase in attempted suicide.

The ACE study's results suggest that maltreatment and household dysfunction in childhood contribute to health problems decades later. These include chronic diseases—such as heart disease, cancer, stroke, and diabetes—that are the most common causes of death and disability in the United States.[145] These findings are important because they provided a link between the effects of child maltreatment and negative effects later in life which had not been established as clearly before this study.

Subsequent surveys

[edit]The ACE Study has produced more than 50 articles that look at the prevalence and consequences of ACEs.[146][147] It has been influential in several areas. Subsequent studies have confirmed the high frequency of adverse childhood experiences.[148]

The original study questions have been used to develop a 10-item screening questionnaire.[149][150] Numerous subsequent surveys have confirmed that adverse childhood experiences are frequent.

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) which is run by the CDC,[151] is an annual survey conducted in waves by groups of individual state and territory health departments. An expanded ACE survey instrument was included in several states found each state.[149] Adverse childhood experiences were even more frequent in studies in urban Philadelphia[152] and in a survey of young mothers (mostly younger than 19).[153] Surveys of adverse childhood experiences have been conducted in multiple EU member countries.[154][155][156]

See also

[edit]- Adverse childhood experiences among Hispanic and Latino Americans

- Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire

- Stress in early childhood

- Social determinants of health

- Verbal abuse

References

[edit]- ^ a b Brown, David W.; Anda, Robert F.; Felitti, Vincent J.; Edwards, Valerie J.; Malarcher, Ann Marie; Croft, Janet B.; Giles, Wayne H. (2010-01-19). "Adverse childhood experiences are associated with the risk of lung cancer: a prospective cohort study". BMC Public Health. 10 (1): 20. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-20. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 2826284. PMID 20085623.

- ^ De Bellis, Michael D; Keshavan, Matcheri S; Clark, Duncan B; Casey, B.J; Giedd, Jay N; Boring, Amy M; Frustaci, Karin; Ryan, Neal D (1999). "Developmental traumatology part II: brain development∗∗See accompanying Editorial, in this issue". Biological Psychiatry. 45 (10): 1271–1284. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00045-1. PMID 10349033. S2CID 14102617.

- ^ Stein, M. B.; Koverola, C.; Hanna, C.; Torchia, M. G.; McClarty, B. (1997). "Hippocampal volume in women victimized by childhood sexual abuse". Psychological Medicine. 27 (4): 951–959. doi:10.1017/S0033291797005242 (inactive 26 December 2024). PMID 9234472. S2CID 25568605.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of December 2024 (link) - ^ Teicher, Martin H.; Ito, Yutaka; Glod, Carol A.; Andersen, Susan L.; Dumont, Natalie; Ackerman, Erika (1997). "Preliminary Evidence for Abnormal Cortical Development in Physically and Sexually Abused Children Using EEG Coherence and MRI". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 821 (1 Psychobiology): 160–175. Bibcode:1997NYASA.821..160T. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48277.x. ISSN 0077-8923. PMID 9238202. S2CID 22071180.

- ^ "Adverse childhood experiences: what support do young people need?". NIHR Evidence. 2022-06-08. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_51024. S2CID 251774877.

- ^ Kalmakis, Karen A.; Chandler, Genevieve E. (2015). "Health consequences of adverse childhood experiences: A systematic review". Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners. 27 (8): 457–465. doi:10.1002/2327-6924.12215. ISSN 2327-6924. PMID 25755161. S2CID 205216619.

- ^ Hughes, Karen; Bellis, Mark A; Hardcastle, Katherine A; Sethi, Dinesh; Butchart, Alexander; Mikton, Christopher; Jones, Lisa; Dunne, Michael P (2017). "The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet Public Health. 2 (8): e356–e366. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4. PMID 29253477. S2CID 3217580.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Dube, Shanta R.; Cook, Michelle L.; Edwards, Valerie J. (2010). "Health-related outcomes of adverse childhood experiences in Texas, 2002". Preventing Chronic Disease. 7 (3): A52. ISSN 1545-1151. PMC 2879984. PMID 20394691.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Dube, Shanta R.; Cook, Michelle L.; Edwards, Valerie J. (2010). "Health-related outcomes of adverse childhood experiences in Texas, 2002". Preventing Chronic Disease. 7 (3): A52. ISSN 1545-1151. PMC 2879984. PMID 20394691.

- ^ a b Asmussen K, Fischer F, Drayton E, McBride T (February 2020). Adverse childhood experiences. What we know, what we don't know, and what should happen next (PDF) (Report). Early Intervention Foundation m.

- ^ "About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022-03-17. Retrieved 2022-07-14.

- ^ a b

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2010-12-17). "Adverse childhood experiences reported by adults --- five states, 2009". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 59 (49): 1609–1613. ISSN 1545-861X. PMID 21160456.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2010-12-17). "Adverse childhood experiences reported by adults --- five states, 2009". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 59 (49): 1609–1613. ISSN 1545-861X. PMID 21160456.

- ^ Giano Z, Wheeler DL, Hubach RD (September 2020). "The frequencies and disparities of adverse childhood experiences in the U.S". BMC Public Health. 20 (1): 1327. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09411-z. PMC 7488299. PMID 32907569.

- ^ Matilda A, Angela D (September 2015). The Impact of Adverse Experiences in the Home on Children and Young People (PDF) (Report). UCL Institute of Health Equity.

- ^ Krug et al., "World report on violence and health" Archived 2015-08-22 at the Wayback Machine, World Health Organization, 2002.

- ^ Stoltenborgh M.; Van IJzendoorn M.H.; Euser E.M.; Bakermans-Kranenburg M.J. (2011). "A global perspective on child abuse: Meta-analysis of prevalence around the world". Child Maltreatment. 26 (2): 79–101. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1029.9752. doi:10.1177/1077559511403920. PMID 21511741. S2CID 30813632.

- ^ Garbarino J (1977). "The Human Ecology of Child Maltreatment: A Conceptual Model for Research". Journal of Marriage and the Family. 39 (4): 721–735. doi:10.2307/350477. JSTOR 350477.

- ^ McCord J (1983). "A forty year perspective on effects of child abuse and neglect". Child Abuse & Neglect. 7 (3): 265–270. doi:10.1016/0145-2134(83)90003-0. PMID 6686471.

- ^ Pearce J, Murray C, Larkin W (July 2019). "Childhood adversity and trauma: experiences of professionals trained to routinely enquire about childhood adversity". Heliyon. 5 (7): e01900. Bibcode:2019Heliy...501900P. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01900. PMC 6658729. PMID 31372522.

- ^ Shonkoff JP, Garner AS (January 2012). "The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress". Pediatrics. 129 (1): e232–e246. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2663. PMID 22201156. S2CID 535692.

- ^ Holmes C, Levy M, Smith A, Pinne S, Neese P (2015-06-01). "A Model for Creating a Supportive Trauma-Informed Culture for Children in Preschool Settings". Journal of Child and Family Studies. 24 (6): 1650–1659. doi:10.1007/s10826-014-9968-6. PMC 4419190. PMID 25972726.

- ^ "The Science of ACEs & Toxic Stress". ACEs Aware. Retrieved 2021-10-16.

- ^ a b Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD, et al. (April 2006). "The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology". European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 256 (3): 174–186. doi:10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. PMC 3232061. PMID 16311898.

- ^ Danese A, McEwen BS (April 2012). "Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease". Physiology & Behavior. 106 (1): 29–39. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.08.019. PMID 21888923. S2CID 3840754.

- ^ Teicher MH. "Windows of Vulnerability: Understanding how early stress alters trajectories of brain development and sets the stage for the emergence of mental disorders" (PDF). The Balanced Mind. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ^ a b Schury K, Kolassa IT (July 2012). "Biological memory of childhood maltreatment: current knowledge and recommendations for future research". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1262 (1): 93–100. Bibcode:2012NYASA1262...93S. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06617.x. PMID 22823440. S2CID 205937864.

- ^ Sorrow A (May 30, 2013). "Study uncovers cost of resiliency in kids". medicalxpress.com. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ^ Moffitt TE (November 2013). "Childhood exposure to violence and lifelong health: clinical intervention science and stress-biology research join forces". Development and Psychopathology. 25 (4 Pt 2). The Klaus-Grawe 2012 Think Tank: 1619–1634. doi:10.1017/S0954579413000801. PMC 3869039. PMID 24342859.

- ^ Rogosch FA, Dackis MN, Cicchetti D (November 2011). "Child maltreatment and allostatic load: consequences for physical and mental health in children from low-income families". Development and Psychopathology. 23 (4): 1107–1124. doi:10.1017/S0954579411000587. PMC 3513367. PMID 22018084.

- ^ Chu AT, Lieberman AF (2010-03-01). "Clinical implications of traumatic stress from birth to age five". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 6 (1): 469–494. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131204. PMID 20192799.

- ^ Benedini KM, Fagan AA, Gibson CL (September 2016). "The cycle of victimization: The relationship between childhood maltreatment and adolescent peer victimization". Child Abuse & Neglect. 59: 111–121. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.08.003. PMID 27568065.

- ^ Hagan MJ, Sulik MJ, Lieberman AF (July 2016). "Traumatic Life Events and Psychopathology in a High Risk, Ethnically Diverse Sample of Young Children: A Person-Centered Approach". Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 44 (5): 833–844. doi:10.1007/s10802-015-0078-8. PMID 26354023. S2CID 13879564.

- ^ Yohros A (February 2022). "Examining the Relationship Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Juvenile Recidivism: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 24 (3): 1640–1655. doi:10.1177/15248380211073846. PMID 35166600. S2CID 246827058.

- ^ a b c d Morgan CA, Chang YH, Choy O, Tsai MC, Hsieh S (December 2021). "Adverse Childhood Experiences Are Associated with Reduced Psychological Resilience in Youth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Children. 9 (1): 27. doi:10.3390/children9010027. PMC 8773896. PMID 35053652.

- ^ Gresham B, Karatekin C (April 2022). "The role of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in predicting academic problems among college students". Child Abuse & Neglect. 142 (Pt 1): 105595. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105595. PMC 10117202. PMID 35382940. S2CID 247926110.

- ^ Allphin M (2020-01-01). "A Meta-analysis on Non-Cognitive Predictors of College Student Academic Performance". Williams Honors College, Honors Research Projects.

- ^ Liu M, Luong L, Lachaud J, Edalati H, Reeves A, Hwang SW (November 2021). "Adverse childhood experiences and related outcomes among adults experiencing homelessness: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet. Public Health. 6 (11): e836–e847. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00189-4. PMID 34599894. S2CID 238254022.

- ^ a b Artigas R, Vega-Tapia F, Hamilton J, Krause BJ (October 2021). "Dynamic DNA methylation changes in early versus late adulthood suggest nondeterministic effects of childhood adversity: a meta-analysis". Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. 12 (5): 768–779. doi:10.1017/S2040174420001075. PMID 33308369. S2CID 229175067.

- ^ Brindle RC, Pearson A, Ginty AT (March 2022). "Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) relate to blunted cardiovascular and cortisol reactivity to acute laboratory stress: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 134: 104530. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104530. PMID 35031343. S2CID 245856379.

- ^ Bransfield RC (June 2022). "Adverse Childhood Events, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Infectious Encephalopathies and Immune-Mediated Disease". Healthcare. 10 (6): 1127. doi:10.3390/healthcare10061127. PMC 9222834. PMID 35742178.

- ^ Bellis MA, Hughes K, Ford K, Madden HC, Glendinning F, Wood S (February 2022). "Associations between adverse childhood experiences, attitudes towards COVID-19 restrictions and vaccine hesitancy: a cross-sectional study". BMJ Open. 12 (2): e053915. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053915. PMC 8829847. PMID 35105582.

- ^ Herzog JI, Schmahl C (2018-09-04). "Adverse Childhood Experiences and the Consequences on Neurobiological, Psychosocial, and Somatic Conditions Across the Lifespan". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 9: 420. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00420. PMC 6131660. PMID 30233435.

- ^ a b Kraaijenvanger EJ, Pollok TM, Monninger M, Kaiser A, Brandeis D, Banaschewski T, Holz NE (June 2020). "Impact of early life adversities on human brain functioning: A coordinate-based meta-analysis". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 113: 62–76. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.03.008. PMID 32169412. S2CID 212656815.

- ^ Barch DM, Shirtcliff EA, Elsayed NM, Whalen D, Gilbert K, Vogel AC, et al. (September 2020). "Testosterone and hippocampal trajectories mediate relationship of poverty to emotion dysregulation and depression". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (36): 22015–22023. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11722015B. doi:10.1073/pnas.2004363117. PMC 7486761. PMID 32839328.

- ^ Maier A, Heinen-Ludwig L, Güntürkün O, Hurlemann R, Scheele D (2020-08-06). "Childhood Maltreatment Alters the Neural Processing of Chemosensory Stress Signals". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 11: 783. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00783. PMC 7425696. PMID 32848947.

- ^ Paquola C, Bennett MR, Lagopoulos J (October 2016). "Understanding heterogeneity in grey matter research of adults with childhood maltreatment-A meta-analysis and review". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 69: 299–312. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.011. PMID 27531235. S2CID 39417214.

- ^ Cassiers LL, Sabbe BG, Schmaal L, Veltman DJ, Penninx BW, Van Den Eede F (2018-08-03). "Structural and Functional Brain Abnormalities Associated With Exposure to Different Childhood Trauma Subtypes: A Systematic Review of Neuroimaging Findings". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 9: 329. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00329. PMC 6086138. PMID 30123142.

- ^ Sapolsky RM (November 2003). "Stress and plasticity in the limbic system". Neurochemical Research. 28 (11): 1735–1742. doi:10.1023/A:1026021307833. PMID 14584827. S2CID 12012982.

- ^ Teicher MH, Samson JA (March 2016). "Annual Research Review: Enduring neurobiological effects of childhood abuse and neglect". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 57 (3): 241–266. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12507. PMC 4760853. PMID 26831814.

- ^ Baker LM, Williams LM, Korgaonkar MS, Cohen RA, Heaps JM, Paul RH (June 2013). "Impact of early vs. late childhood early life stress on brain morphometrics". Brain Imaging and Behavior. 7 (2): 196–203. doi:10.1007/s11682-012-9215-y. PMC 8754232. PMID 23247614.

- ^ Teicher MH, Samson JA, Anderson CM, Ohashi K (September 2016). "The effects of childhood maltreatment on brain structure, function and connectivity". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 17 (10): 652–666. doi:10.1038/nrn.2016.111. PMID 27640984. S2CID 27336625.

- ^ Merrick MT, Ford DC, Ports KA, Guinn AS, Chen J, Klevens J, et al. (November 2019). "Vital Signs: Estimated Proportion of Adult Health Problems Attributable to Adverse Childhood Experiences and Implications for Prevention – 25 States, 2015–2017". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 68 (44): 999–1005. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6844e1. PMC 6837472. PMID 31697656.

- ^ Hughes K, Ford K, Bellis MA, Glendinning F, Harrison E, Passmore J (November 2021). "Health and financial costs of adverse childhood experiences in 28 European countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet. Public Health. 6 (11): e848–e857. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00232-2. PMC 8573710. PMID 34756168.

- ^ Manyema M, Richter LM (December 2019). "Adverse childhood experiences: prevalence and associated factors among South African young adults". Heliyon. 5 (12): e03003. Bibcode:2019Heliy...503003M. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e03003. PMC 6926197. PMID 31890957.

- ^ Ho GW, Bressington D, Karatzias T, Chien WT, Inoue S, Yang PJ, et al. (March 2020). "Patterns of exposure to adverse childhood experiences and their associations with mental health: a survey of 1346 university students in East Asia" (PDF). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 55 (3): 339–349. doi:10.1007/s00127-019-01768-w. PMID 31501908. S2CID 201965787.

- ^ a b c d Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, Sethi D, Butchart A, Mikton C, et al. (August 2017). "The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet. Public Health. 2 (8): e356–e366. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4. PMID 29253477. S2CID 3217580.

- ^ Lin WH, Chiao C (January 2022). "The Relationship Between Adverse Childhood Experience and Heavy Smoking in Emerging Adulthood: The Role of Not in Education, Employment, or Training Status". The Journal of Adolescent Health. 70 (1): 155–162. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.07.022. PMID 34518067. S2CID 237508856.

- ^ Baiden P, Onyeaka HK, Kyeremeh E, Panisch LS, LaBrenz CA, Kim Y, Kunz-Lomelin A (2022-02-23). "An Association of Adverse Childhood Experiences with Binge Drinking in Adulthood: Findings from a Population-Based Study". Substance Use & Misuse. 57 (3): 360–372. doi:10.1080/10826084.2021.2012692. PMID 35023435. S2CID 245907315.

- ^ Schroeder K, Schuler BR, Kobulsky JM, Sarwer DB (July 2021). "The association between adverse childhood experiences and childhood obesity: A systematic review". Obesity Reviews. 22 (7): e13204. doi:10.1111/obr.13204. PMC 8192341. PMID 33506595.

- ^ a b Wiss DA, Brewerton TD (September 2020). "Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adult Obesity: A Systematic Review of Plausible Mechanisms and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional Studies". Physiology & Behavior. 223: 112964. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.112964. PMID 32479804. S2CID 219123694.

- ^ Waehrer GM, Miller TR, Silverio Marques SC, Oh DL, Burke Harris N (2020-01-28). Seedat S (ed.). "Disease burden of adverse childhood experiences across 14 states". PLOS ONE. 15 (1): e0226134. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1526134W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0226134. PMC 6986706. PMID 31990910.

- ^ Monnat SM, Chandler RF (September 2015). "Long Term Physical Health Consequences of Adverse Childhood Experiences". The Sociological Quarterly. 56 (4): 723–752. doi:10.1111/tsq.12107. PMC 4617302. PMID 26500379.

- ^ Lopes S, Hallak JE, Machado de Sousa JP, Osório FL (2020-12-31). "Adverse childhood experiences and chronic lung diseases in adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis". European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 11 (1): 1720336. doi:10.1080/20008198.2020.1720336. PMC 7034480. PMID 32128046.

- ^ Jacquet-Smailovic M, Brennstuhl MJ, Tarquinio CL, Tarquinio C (2021-09-22). "Relationship Between Cumulative Adverse Childhood Experiences and Myocardial Infarction in Adulthood: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma. 15 (3): 701–714. doi:10.1007/s40653-021-00404-7. PMC 9360358. PMID 35958714. S2CID 240525653.

- ^ a b Hu Z, Kaminga AC, Yang J, Liu J, Xu H (July 2021). "Adverse childhood experiences and risk of cancer during adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Child Abuse & Neglect. 117: 105088. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105088. PMID 33971569. S2CID 234361307.

- ^ Subramaniam M, Abdin E, Vaingankar JA, Chang S, Sambasivam R, Jeyagurunathan A, et al. (March 2021). "Association of adverse childhood experiences with diabetes in adulthood: results of a cross-sectional epidemiological survey in Singapore". BMJ Open. 11 (3): e045167. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045167. PMC 7959232. PMID 33722874.

- ^ Amemiya A, Fujiwara T, Shirai K, Kondo K, Oksanen T, Pentti J, Vahtera J (August 2019). "Association between adverse childhood experiences and adult diseases in older adults: a comparative cross-sectional study in Japan and Finland". BMJ Open. 9 (8): e024609. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024609. PMC 6720330. PMID 31446402.

- ^ Tietjen GE, Khubchandani J, Herial NA, Shah K (June 2012). "Adverse childhood experiences are associated with migraine and vascular biomarkers". Headache. 52 (6): 920–929. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02165.x. PMID 22533684. S2CID 25651656.

- ^ Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, et al. (November 2010). "Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 197 (5): 378–385. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499. PMC 2966503. PMID 21037215.

- ^ Fletcher-Janzen, Elaine (2021). "Translating ACE Research into Multi-tiered Systems of Supports for At-risk High-school Students". Journal of Pediatric Neuropsychology. 7 (4): 89–101. doi:10.1007/s40817-020-00093-4 – via Springer.

- ^ Ege MA, Messias E, Thapa PB, Krain LP (January 2015). "Adverse childhood experiences and geriatric depression: results from the 2010 BRFSS". The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 23 (1): 110–114. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2014.08.014. PMC 4267899. PMID 25306195.

- ^ Chen H, Fan Q, Nicholas S, Maitland E (August 2021). "The long arm of childhood: The prolonged influence of adverse childhood experiences on depression during middle and old age in China". Journal of Health Psychology. 27 (10): 2373–2389. doi:10.1177/13591053211037727. PMID 34397302. S2CID 237092920.

- ^ Jimenez ME, Wade R, Schwartz-Soicher O, Lin Y, Reichman NE (2017). "Adverse Childhood Experiences and ADHD Diagnosis at Age 9 Years in a National Urban Sample". Academic Pediatrics. 17 (4): 356–361. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2016.12.009. PMC 5555409. PMID 28003143.

- ^ Li M, D'Arcy C, Meng X (March 2016). "Maltreatment in childhood substantially increases the risk of adult depression and anxiety in prospective cohort studies: systematic review, meta-analysis, and proportional attributable fractions". Psychological Medicine. 46 (4): 717–730. doi:10.1017/S0033291715002743. PMID 26708271. S2CID 206255564.

- ^ Giano Z, Hubach RD (December 2019). "Adverse childhood experiences and mental health: Comparing the link in rural and urban men who have sex with men". Journal of Affective Disorders. 259: 362–369. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.044. PMID 31470179. S2CID 201786187.

- ^ Blosnich JR, Garfin DR, Maguen S, Vogt D, Dichter ME, Hoffmire CA, et al. (2021). "Differences in childhood adversity, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt among veterans and nonveterans". The American Psychologist. 76 (2): 284–299. doi:10.1037/amp0000755. PMC 8638657. PMID 33734795.

- ^ Carbone EA, Pugliese V, Bruni A, Aloi M, Calabrò G, Jaén-Moreno MJ, et al. (December 2019). "Adverse childhood experiences and clinical severity in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: A transdiagnostic two-step cluster analysis". Journal of Affective Disorders. 259: 104–111. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.049. PMID 31445335. S2CID 201644851.

- ^ a b c d e f g Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. (May 1998). "Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 14 (4): 245–258. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. PMID 9635069.

- ^ Keener AB (25 January 2021). "Unseen scars of childhood trauma". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-012521-1. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ Hemady, C. L., et al. (2022). Patterns of adverse childhood experiences and associations with prenatal substance use and poor infant outcomes in a multi-country cohort of mothers: A latent class analysis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 22, 1-12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04839-0

- ^ Massetti GM, Hughes K, Bellis MA, Mercy J (2020). "Global perspective on ACEs". Adverse Childhood Experiences. Elsevier. pp. 209–231. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-816065-7.00011-2. ISBN 978-0-12-816065-7. S2CID 212831040.

- ^ Piotrowski CC (2020). "ACEs and trauma-informed care". Adverse Childhood Experiences. Elsevier. pp. 307–328. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-816065-7.00015-x. ISBN 978-0-12-816065-7. S2CID 214395921.

- ^ Oshri A, Duprey EK, Liu S, Gonzalez A (2020). "ACEs and resilience: Methodological and conceptual issues". Adverse Childhood Experiences. Elsevier. pp. 287–306. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-816065-7.00014-8. ISBN 978-0-12-816065-7. S2CID 213941455.

- ^ Waterhouse JA (2022-02-02). "Adverse childhood experiences, safeguarding and the role of the school nurse in promoting resilience and wellbeing". British Journal of Child Health. 3 (1): 29–37. doi:10.12968/chhe.2022.3.1.29. S2CID 247643462.

- ^ Bodendorfer V, Koball AM, Rasmussen C, Klevan J, Ramirez L, Olson-Dorff D (July 2020). "Implementation of the adverse childhood experiences conversation in primary care". Family Practice. 37 (3): 355–359. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmz065. PMID 31758184.

- ^ Dube SR (2020). "Twenty years and counting: The past, present, and future of ACEs research". Adverse Childhood Experiences. Elsevier. pp. 3–16. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-816065-7.00001-x. ISBN 978-0-12-816065-7. S2CID 214232764.

- ^ Kaminer D, Bravo AJ, Mezquita L, Pilatti A, Bravo AJ, Conway CC, et al. (Cross-Cultural Addictions Study Team) (2022-03-29). "Adverse childhood experiences and adulthood mental health: a cross-cultural examination among university students in seven countries". Current Psychology. 42 (21): 18370–18381. doi:10.1007/s12144-022-02978-3. hdl:10234/199658. S2CID 247835374.

- ^ Radford A, Toombs E, Zugic K, Boles K, Lund J, Mushquash CJ (June 2022). "Examining Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) within Indigenous Populations: a Systematic Review". Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma. 15 (2): 401–421. doi:10.1007/s40653-021-00393-7. PMC 9120316. PMID 35600513.

- ^ a b Brockie TN, Elm JH, Walls ML (September 2018). "Examining protective and buffering associations between sociocultural factors and adverse childhood experiences among American Indian adults with type 2 diabetes: a quantitative, community-based participatory research approach". BMJ Open. 8 (9): e022265. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022265. PMC 6150153. PMID 30232110.

- ^ a b Matlin SL, Champine RB, Strambler MJ, O'Brien C, Hoffman E, Whitson M, et al. (December 2019). "A Community's Response to Adverse Childhood Experiences: Building a Resilient, Trauma-Informed Community". American Journal of Community Psychology. 64 (3–4): 451–466. doi:10.1002/ajcp.12386. PMC 6917911. PMID 31486086.

- ^ Stevens JE (25 September 2012). "Community Projects". ACEs Connection.

- ^ "PEACE4TARPON Trauma Informed Community Initiative". 30 March 2014.

- ^ Stevens JE (13 February 2012). "Tarpon Springs, FL, may be first trauma-informed city in U.S." ACEs Too High.

- ^ a b Blodgett C, Lanigan JD (March 2018). "The association between adverse childhood experience (ACE) and school success in elementary school children". School Psychology Quarterly. 33 (1): 137–146. doi:10.1037/spq0000256. PMID 29629790. S2CID 4717363.

- ^ a b Plumb JL, Bush KA, Kersevich SE (2016). "Trauma-Sensitive Schools: An Evidence Based Approach". School Social Work Journal. 40 (2): 37–60.

- ^ Stevens JE (28 February 2012). "Spokane, WA, students' trauma prompts search for solutions". ACEs Too High.

- ^ Stevens JE (31 May 2012). "Massachusetts, Washington State lead U.S. trauma-sensitive school movement". ACEs Too High.

- ^ Blodgett C (2013). "A Review of Community Efforts to Mitigate and Prevent Adverse Childhood Experiences and Trauma" (PDF). Washington State University Health Education Center: Spokane, WA.

- ^ National Child Traumatic Stress Network, Schools Committee. (2017). "Creating, Supporting, and Sustaining Trauma-Informed Schools: A System Framework" (PDF). Los Angeles, CA and Durham, NC: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress.

- ^ Dorado JS, Martinez M, McArthur LE, Leibovitz T (2016). "Healthy Environments and Response to Trauma in Schools (HEARTS): A Whole-School, Multi-Level, Prevention and Intervention Program for Creating Trauma-Informed Safe and Supportive Schools". School Mental Health. 8 (1): 163–176. doi:10.1007/s12310-016-9177-0. S2CID 146359339.

- ^ "Sex Between Students & Professors". Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ "Has Media Ignored Sex Abuse In School?". www.cbsnews.com. 24 August 2006. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2009.[title missing]

- ^ a b c d e Buchanan, Rebecca; Davis, Lauren; Cury, Trisha (2021). "Putting research into "action": the impact of brain energizers on off-task behaviors and academic achievement". Networks: An Online Journal for Teacher Research. 23 (1). doi:10.4148/2470-6353.1325. S2CID 234852891.

- ^ Allen, LaRue; Kelly, Bridget B.; Success, Committee on the Science of Children Birth to Age 8: Deepening and Broadening the Foundation for; Board on Children, Youth; Medicine, Institute of; Council, National Research (23 July 2015). Child Development and Early Learning. National Academies Press (US). Retrieved 5 December 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Goldstein, Ellen; Topitzes, James; Miller-Cribbs, Julie; Brown, Roger (2021). "Influence of race/ethnicity and income on the link between adverse childhood experiences and child flourishing". Pediatric Research. 89 (7): 1861–1869. doi:10.1038/s41390-020-01188-6. PMC 8249234. PMID 33045719. S2CID 222319153.

- ^ a b c d Snow, Pamela (2021). "Psychosocial adversity in early childhood and language and literacy skills in adolescence: the role of speech-language pathology in prevention, policy, and practice". Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups. 6 (2): 253–261. doi:10.1044/2020_PERSP-20-00120. S2CID 229405882.

- ^ a b c Kupzyk, Sara; Banks, Brea; Chadwell, Mindy (2016). "Collaborating with refugee families to increase early literacy opportunities: a pilot investigation". Contemporary School Psychology. 20 (3): 205–217. doi:10.1007/s40688-015-0074-6. S2CID 74414328.

- ^ a b Morrow, Anne; Villodas, Miguel (2018). "Direct and indirect pathways from adverse childhood experiences to high school dropout among high-risk adolescents". Journal of Research on Adolescence. 28 (2): 327–341. doi:10.1111/jora.12332. PMID 28736884. S2CID 21779441.

- ^ Guerrero, A; Herman, A; Teutsch, C; Dudovitz, R (2022). "Improving knowledge and attitudes about child trauma among parents and staff in head start programs". Maternal and Child Health Journal: 1–10 – via EBSCOhost.

- ^ Dutro, Elizabeth (2013). "Towards a pedagogy of the incomprehensible: trauma and the imperative of critical witness in literacy classrooms". Pedagogies. 8 (4): 301–315. doi:10.1080/1554480X.2013.829280. S2CID 143651343.

- ^ a b Meister C (July 2012). "Addressing Child Traumatic Stress in Child Welfare" (PDF). Common Ground. XXVI (1): 9.

- ^ "Family-Informed Trauma Treatment Center". 15 July 2014.

- ^ Stevens JE (30 July 2012). "'Starve the beast,' say these cities – but don't cut people off; reduce need for services instead". ACEs Too High.

- ^ a b Bebout R (Winter 2010–2011). "Waiting on the welcome mat: How to be at home with trauma-informed care". camh Cross Currents. Archived from the original on 2016-01-27.

- ^ ACEs 360. "ACEs 360-New York". Archived from the original on 2014-04-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "What support do young people affected by adverse childhood experiences need?". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). 2021-09-02. doi:10.3310/alert_47388. S2CID 244103874.

- ^ Lester S, Khatwa M, Sutcliffe K (November 2020). "Service needs of young people affected by adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): A systematic review of UK qualitative evidence". Children and Youth Services Review. 118: 105429. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105429. PMC 7467867. PMID 32895586.

- ^ Lester S, Lorenc T, et al. (2019). What helps to support people affected by Adverse Childhood Experiences? A Review of Evidence (PDF). EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education, University College London.

- ^ Ruiz R (7 July 2014). "How Childhood Trauma Could Be Mistaken for ADHD". The Atlantic.

- ^ Stevens JE (29 July 2014). "To prevent childhood trauma, pediatricians screen children and their parents…and sometimes, just parents…for childhood trauma". ACEs Too High.

- ^ American Academy of Pediatrics. "Promoting Children's Health and Resiliency: A Strengthening Families Approach" (PDF). Center for the Study of Social Policy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-09-03.

- ^ Lorenc T, Lester S, Sutcliffe K, Stansfield C, Thomas J (May 2020). "Interventions to support people exposed to adverse childhood experiences: systematic review of systematic reviews". BMC Public Health. 20 (1): 657. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-08789-0. PMC 7216383. PMID 32397975.

- ^ a b "10 Questions Some Doctors Are Afraid to Ask". NPR.org.

- ^ McLennan JD, MacMillan HL, Afifi TO (March 2020). "Questioning the use of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) questionnaires". Child Abuse & Neglect. 101: 104331. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104331. PMID 31887655. S2CID 209520160.

- ^ Hellerstedt WL (Spring 2013). "Adverse Childhood Experience: Public Health Surveillance Measures". Healthy Generations. pp. 16–19. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2016.

- ^ de Terte I, Stephens C (December 2014). "Psychological resilience of workers in high-risk occupations". Stress and Health. 30 (5): 353–355. doi:10.1002/smi.2627. PMID 25476960.

- ^ Coleman SR, Zawadzki MJ, Heron KE, Vartanian LR, Smyth JM (2016-02-17). "Self-focused and other-focused resiliency: Plausible mechanisms linking early family adversity to health problems in college women". Journal of American College Health. 64 (2): 85–95. doi:10.1080/07448481.2015.1075994. PMC 10691655. PMID 26502997. S2CID 6101456.

- ^ Cameron LD, Carroll P, Hamilton WK (May 2018). "Evaluation of an intervention promoting emotion regulation skills for adults with persisting distress due to adverse childhood experiences". Child Abuse & Neglect. 79: 423–433. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.002. PMID 29544158. S2CID 4539685.

- ^ Nurius PS, Green S, Logan-Greene P, Borja S (July 2015). "Life course pathways of adverse childhood experiences toward adult psychological well-being: A stress process analysis". Child Abuse & Neglect. 45: 143–153. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.03.008. PMC 4470711. PMID 25846195.

- ^ Jones TM, Nurius P, Song C, Fleming CM (June 2018). "Modeling life course pathways from adverse childhood experiences to adult mental health". Child Abuse & Neglect. 80: 32–40. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.005. PMC 5953821. PMID 29567455.

- ^ Spratt T, Kennedy M (2021-05-18). "Adverse Childhood Experiences: Developments in Trauma and Resilience Aware Services". The British Journal of Social Work. 51 (3): 999–1017. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcaa080.

- ^ Bellis MA, Hardcastle K, Ford K, Hughes K, Ashton K, Quigg Z, Butler N (March 2017). "Does continuous trusted adult support in childhood impart life-course resilience against adverse childhood experiences – a retrospective study on adult health-harming behaviours and mental well-being". BMC Psychiatry. 17 (1): 110. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1260-z. PMC 5364707. PMID 28335746.

- ^ Narayan AJ, Lieberman AF, Masten AS (April 2021). "Intergenerational transmission and prevention of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)". Clinical Psychology Review. 85: 101997. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2021.101997. PMID 33689982. S2CID 232194137.

- ^ Anda, Robert F. (1999-11-03). "Adverse Childhood Experiences and Smoking During Adolescence and Adulthood". JAMA. 282 (17): 1652–1658. doi:10.1001/jama.282.17.1652. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 10553792.

- ^ a b Dube, Shanta R; Anda, Robert F; Felitti, Vincent J; Croft, Janet B; Edwards, Valerie J; Giles, Wayne H (2001). "Growing up with parental alcohol abuse". Child Abuse & Neglect. 25 (12): 1627–1640. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00293-9. PMID 11814159.

- ^ a b c Stevens JE (8 October 2012). "The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study — the Largest Public Health Study You Never Heard Of". The Huffington Post.

- ^ "Prevalence of Individual Adverse Childhood Experiences". cdc.gov. Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. May 2014. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016.

- ^ a b c Anda RF, Felitti VJ (April 2003). "Origins and Essence of the Study" (PDF). ACE Reporter. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ "The ACE Pyramid". Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. May 2014. Archived from the original on 16 January 2016.

- ^ "About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. Archived from the original on 28 February 2015.

- ^ "Revised ACEs Pyramid" (PDF).

- ^ "American Psychologist Article". American Psychologist.

- ^ a b c "Adverse Childhood Experiences". samhsa.gov. Rockville, Maryland, US: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ Mandelli L, Petrelli C, Serretti A (September 2015). "The role of specific early trauma in adult depression: A meta-analysis of published literature. Childhood trauma and adult depression". European Psychiatry. 30 (6): 665–680. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.04.007. PMID 26078093. S2CID 10726299.

- ^ Middlebrooks JS, Audage NC (2008). The Effects of Childhood Stress on Health Across the Lifespan (PDF). Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-02-05. Retrieved 2016-01-29.

- ^ World Health Organization; International Society for Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect (2006). Preventing child maltreatment: a guide to taking action and generating evidence (PDF). Geneva, Switzerland. p. 12. ISBN 978-9241594363.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Petruccelli K, Davis J, Berman T (November 2019). "Adverse childhood experiences and associated health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Child Abuse & Neglect. 97: 104127. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104127. PMID 31454589. S2CID 201653078.

- ^ "Publications by Health Outcome". cdc.gov. Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. May 2014. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016.

- ^ McCutchen C, Hyland P, Shevlin M, Cloitre M (July 2022). "The occurrence and co-occurrence of ACEs and their relationship to mental health in the United States and Ireland". Child Abuse & Neglect. 129: 105681. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105681. PMID 35643057. S2CID 249114918.

- ^ a b Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (December 2010). "Adverse childhood experiences reported by adults --- five states, 2009". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 59 (49): 1609–1613. PMID 21160456.

- ^ Anda R (2007). "Finding Your ACE Score" (PDF). Acestudy.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2016.

- ^ Gudmunson CG, Ryherd LM, Bougher K, Downey JC, Zhang D, et al. (Central Iowa ACEs Steering Committee). "Adverse Childhood Experiences in Iowa: A New Way of Understanding Lifelong Health: Findings From the 2012 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System" (PDF).

- ^ "The Philadelphia Urban ACE Study". 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ Stevens JE (November 2, 2012). "Survey finds teen, young mothers using Crittenton services have alarmingly high ACE scores". ACEs Too High!. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ Baban A, Cosma A, Balazsi R, Sethi D, Olsavszky V (2013). "Survey of Adverse Childhood Experiences among Romanian university students" (PDF). World Health Organization.

- ^ "Adverse childhood experiences survey among young people in the Czech Republic". World Health Organization. December 23, 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ Raleva M, Jordanova Peshevska D, Sethi D (2013). "Survey of Adverse Childhood Experiences Among Young People in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

Further reading

[edit]External links

[edit]- Adverse Childhood Experiences Resources Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- ACEs and Toxic Stress FAQ, Harvard Center on the Developing Child

- Veto Violence