Abra (province)

Abra | |

|---|---|

(from top: left to right) Bangued, Tayum Church, Abra Provincial Capitol, Bucay Casa Real, San Quintin and Abra River. | |

Location in the Philippines | |

| Coordinates: 17°35′N 120°45′E / 17.58°N 120.75°E | |

| Region | Cordillera Administrative Region |

| Founded | March 10, 1917 |

| Capital and largest municipality | Bangued |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Dominic B. Valera (NUP/ASENSO)[a] Russell Bragas (acting) |

| • Vice Governor | Maria Jocelyn V. Bernos[b][2][c] (NUP/ASENSO) Russell Bragas (acting) |

| • Legislature | Abra Provincial Board |

| Area | |

• Total | 4,165.25 km2 (1,608.21 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 29th out of 81 |

| Highest elevation | 2,467 m (8,094 ft) |

| Population (2020 census)[6] | |

• Total | 250,985 |

| • Rank | 68th out of 81 |

| • Density | 60/km2 (160/sq mi) |

| • Rank | 80th out of 81 |

| Demonyms |

|

| Divisions | |

| • Independent cities | 0 |

| • Component cities | 0 |

| • Municipalities | |

| • Barangays | 303 |

| • Districts | Legislative districts of Abra |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (PHT) |

| IDD : area code | +63 (0)74 |

| ISO 3166 code | PH-ABR |

| Spoken languages | |

| Website | www |

Abra, officially the Province of Abra (Ilocano: Probinsia ti Abra; Tagalog: Lalawigan ng Abra), is a province in the Cordillera Administrative Region of the Philippines. Its capital is the municipality of Bangued, the most populous in the province. It is bordered by Ilocos Norte on the northwest, Apayao on the northeast, Kalinga on the mid-east, Mountain Province on the southeast, and Ilocos Sur on the southwest.

Etymology

[edit]Abra is from the Spanish word abra meaning gorge, pass, breach or opening. It was first used by the Spaniards to denote the region above the Banaoang Gap where the Abra River exits into the West Philippine Sea, thus the Rio Grande de Abra.[7]

History

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2015) |

Early history

[edit]The first inhabitants of Abra were the ancestors of the Bontocs and the Ifugaos. These inhabitants eventually left to settle in the old Mountain Province. Other early inhabitants were the Tinguians or Itnegs.

Spanish colonial era

[edit]In 1585, the Tinguians were mentioned for the first time in a letter from Father Domingo de Salazar to the King of Spain.

In 1598 Bangued was occupied by Spanish-Iloco forces. The Spanish established a garrison to protect their missionaries from head hunters so that they could Christianize the Tinguians and locate gold mines. This led to the Ilocano settlement of this area.

Bangued was under the care of the Spanish missions in Vigan and Bantay. Fr. Esteban Marin and Fr. Agustin Minon established a mission in Bangued as early as 1598. On April 5, 1612, Fr. Pedro Columbo became the first minister. It would seem that this actuation of the Augustinians was precipitated by the Dominican take-over of the ministry of Narvacan since the Dominicans wanted to convert Narvacan into a mission center to evangelize the other parts of Abra. To check this Dominican move, the Augustinians elevated Bangued to a ministry.

Fr. Juan Pareja OSA, a former parish priest in Bantay, led the conversion of the province. He came to Abra in 1626 and is reported to have converted as many as 3,000 inhabitants including the chieftain Miguel Dumaoal. He founded the mission of San Diego and later the ministry of Bangued. He established the following towns as visitas of Bangued: Tayum, Sabangan and Bucao (now Dolores). Inspired by Fr. Pareja these towns battled almost daily against the rancherias of Palang, Talamuy, Bataan, Cabulao, Calaoag, and Langiden.

Fr. Jose Polanco OP also contributed to the conversion of Abra. A man of austere mortification, he died in Abra in 1679 and was considered a saint by the locals.

Fr. Bernardino Lago OSA arrived in the early 19th century. In 1823, Fr. Lago began work in Pidigan. After 25 years the Christians were numbered about a thousand "baptized, living in community, with schools, church and municipal house, tilling the earth to support themselves and their children." Fr. Lago also founded the town of La Paz. Fr. Galende enumerates the foundation of the other towns of Abra:

- Tayum, 1803

- San Gregorio, 1829

- Pidigan, 1823

- La Paz, 1832

- Bucay, 1847

- San Jose, 1848

- Villavieja, 1862

- San Quintin, 1868

- Dolores, 1882

- Pilar, 1882

- San Juan, 1884

- Alfonso XII, 1884

Originally the area was called El Abra de Vigan ("The Opening of Vigan"). During the British Occupation of the Philippines, Gabriela Silang and her army fled to Abra from Ilocos and continued the revolt begun by her slain husband Diego Silang. She was captured and hanged by authorities in 1763.

In 1818, the Ilocos region was divided into Ilocos Norte and Ilocos Sur. On October 9, 1846, Abra became an independent province with the capital and residence of the provincial governor located in Bucay. In 1863 the capital was transferred to Bangued, the province's oldest town. It remained so until the arrival of the Americans in 1899.

American occupation

[edit]In 1908, the Philippine Commission annexed Abra into Ilocos Sur in an attempt to resolve Abra's financial difficulties. On March 9, 1917, the Philippine Assembly re-established Abra as a province under Act 2683.[8]

Japanese occupation

[edit]During World War II, Japanese forces occupied Abra in 1942. The province was liberated by Filipino soldiers and guerrillas in 1945.[further explanation needed]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2016) |

Under the Marcos dictatorship

[edit]The beginning months of the 1970s marked a period of turmoil and change in the Philippines, as well as in Abra.[9] During his bid to be the first Philippine president to be re-elected for a second term, Ferdinand Marcos launched an unprecedented number of public works projects. This caused[10][11] the Philippine economy took a sudden downwards turn known as the 1969 Philippine balance of payments crisis, which in turn led to a period of economic difficulty and social unrest.[12][13] : "43" [14][15]

With only a year left in his last constitutionally allowed term as president, Ferdinand Marcos placed the Philippines under Martial Law in September 1972 and thus retained the position for fourteen more years.[16] This period in Philippine history is remembered for the Marcos administration's record of human rights abuses,[17][18] particularly targeting political opponents, student activists, journalists, religious workers, farmers, and others who fought against the Marcos dictatorship.[19] In Abra, many of the victims were from the indigenous Itneg people (known then among most lowlanders as the Tingguian people, which is an exonym). Numerous human rights abuses against Itnegs were documented in the various Amnesty International missions which allowed to conduct investigations in the country after Marcos had to give in to political pressure.[20]

On May 6, 1983, Sitio Beew in the Municipality of Tubo was the site of several attacks by the 623rd Philippine Constabulary (623rd PC) led by Captain Berido, Lt. Rehaldo Lebua and Lt. Juanito Puyawan, which would collectively come to be known as the "Beew massacre." The 623rd PC burned down four houses and a rice granary, which still contained the remains of three villagers including an unborn baby, and Barangay Councilman Rodolfo Labawig, pregnant mother Josefina Cayandag, and her unborn child.[21] Beew residents, including babies and toddlers, were beaten and their houses looted in response to the residents' alleged support of protests against the logging operations of Herminio Disini's Cellophil Resources Corporation in their area.[21]

Later 20th Century

[edit]The revolutionary Marxist priest Conrado Balweg, who fought for the rights of the Cordillera tribes, began his crusade in Abra. After successfully negotiating a peace accord with Balweg's group in 1987, the Philippine government created the Cordillera Administrative Region, which includes Abra.[22]

Contemporary history

[edit]On July 27, 2022, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake, jolted the province. Eleven people died (at least seven of them were from Abra) and more than 600 were injured.[23] A magnitude 6.4 aftershock three months later injured more than 100 people and caused additional damage.[24]

Geography

[edit]Abra is situated in the mid-western section of the Cordillera Administrative Region in Luzon. It is bordered by the provinces of Ilocos Norte on the northwest, Apayao on the northeast, Kalinga on the mid-east, Mountain Province on the southeast and Ilocos Sur on the southwest. Abra has a total land area of 4,165.25 square kilometres or 1,608.21 square miles[25].

The province is bordered by the towering mountain ranges of the Ilocos in the west and the Cordillera Central in the east. The Abra River runs from the south in Benguet to the west and central areas bisecting the Abra Valley. It is joined by the Tineg River originating in the eastern uplands at a point near the municipality of Dolores.

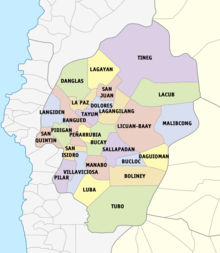

Administrative divisions

[edit]Abra is composed of 27 municipalities, all encompassed by Abra's lone congressional district.[25]

| Municipality [i][ii] | Population | ±% p.a. | Area[25] | Density (2020) | Barangay | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (2020)[6] | (2015)[26] | km2 | sq mi | /km2 | /sq mi | |||||||

| 17°35′47″N 120°37′04″E / 17.5965°N 120.6179°E | Bangued | † | 20.1% | 50,382 | 48,163 | +0.86% | 136.40 | 52.66 | 370 | 960 | 31 | |

| 17°22′44″N 120°49′11″E / 17.3790°N 120.8198°E | Boliney | 1.8% | 4,551 | 3,573 | +4.71% | 210.00 | 81.08 | 22 | 57 | 8 | ||

| 17°32′20″N 120°43′00″E / 17.5388°N 120.7167°E | Bucay | 7.4% | 17,953 | 17,115 | +0.91% | 102.16 | 39.44 | 180 | 470 | 21 | ||

| 17°26′27″N 120°51′26″E / 17.4409°N 120.8572°E | Bucloc | 1.0% | 2,395 | 2,501 | −0.82% | 63.77 | 24.62 | 38 | 98 | 4 | ||

| 17°27′30″N 120°55′31″E / 17.4584°N 120.9254°E | Daguioman | 0.8% | 2,019 | 2,088 | −0.64% | 114.37 | 44.16 | 18 | 47 | 4 | ||

| 17°41′03″N 120°39′35″E / 17.6841°N 120.6597°E | Danglas | 1.6% | 4,074 | 4,192 | −0.54% | 156.02 | 60.24 | 26 | 67 | 7 | ||

| 17°38′56″N 120°42′37″E / 17.6490°N 120.7103°E | Dolores | 4.6% | 11,512 | 11,315 | +0.33% | 47.45 | 18.32 | 240 | 620 | 15 | ||

| 17°40′35″N 120°41′07″E / 17.6763°N 120.6853°E | La Paz | 6.6% | 16,493 | 15,437 | +1.27% | 51.41 | 19.85 | 320 | 830 | 12 | ||

| 17°39′48″N 120°56′51″E / 17.6634°N 120.9474°E | Lacub | 1.4% | 3,612 | 3,403 | +1.14% | 235.53 | 90.94 | 15 | 39 | 6 | ||

| 17°36′37″N 120°44′04″E / 17.6103°N 120.7344°E | Lagangilang | 5.9% | 14,914 | 14,255 | +0.86% | 124.20 | 47.95 | 120 | 310 | 17 | ||

| 17°43′15″N 120°42′21″E / 17.7207°N 120.7058°E | Lagayan | 1.8% | 4,488 | 4,499 | −0.05% | 215.97 | 83.39 | 21 | 54 | 5 | ||

| 17°34′37″N 120°33′50″E / 17.5769°N 120.5638°E | Langiden | 1.4% | 3,576 | 3,198 | +2.15% | 116.29 | 44.90 | 31 | 80 | 6 | ||

| 17°36′22″N 120°53′36″E / 17.6061°N 120.8932°E | Licuan-Baay (Licuan) | 1.8% | 4,566 | 4,689 | −0.50% | 256.42 | 99.00 | 18 | 47 | 11 | ||

| 17°19′05″N 120°41′43″E / 17.3181°N 120.6952°E | Luba | 2.6% | 6,518 | 6,339 | +0.53% | 148.27 | 57.25 | 44 | 110 | 8 | ||

| 17°33′49″N 120°59′24″E / 17.5636°N 120.9899°E | Malibcong | 1.6% | 4,027 | 3,428 | +3.11% | 283.17 | 109.33 | 14 | 36 | 12 | ||

| 17°25′59″N 120°42′17″E / 17.4331°N 120.7048°E | Manabo | 4.6% | 11,611 | 10,761 | +1.46% | 81.08 | 31.31 | 140 | 360 | 11 | ||

| 17°33′51″N 120°39′08″E / 17.5642°N 120.6522°E | Peñarrubia | 2.8% | 6,951 | 6,640 | +0.88% | 39.07 | 15.09 | 180 | 470 | 9 | ||

| 17°34′13″N 120°35′21″E / 17.5703°N 120.5893°E | Pidigan | 5.0% | 12,475 | 12,185 | +0.45% | 49.15 | 18.98 | 250 | 650 | 15 | ||

| 17°25′00″N 120°35′43″E / 17.4168°N 120.5954°E | Pilar | 4.0% | 10,146 | 10,223 | −0.14% | 66.10 | 25.52 | 150 | 390 | 19 | ||

| 17°27′18″N 120°45′36″E / 17.4551°N 120.7599°E | Sallapadan | 2.5% | 6,389 | 6,622 | −0.68% | 128.62 | 49.66 | 50 | 130 | 9 | ||

| 17°27′56″N 120°36′06″E / 17.4656°N 120.6017°E | San Isidro | 1.9% | 4,745 | 4,574 | +0.70% | 48.07 | 18.56 | 99 | 260 | 9 | ||

| 17°41′00″N 120°43′55″E / 17.6834°N 120.7320°E | San Juan | 4.3% | 10,688 | 9,867 | +1.53% | 64.08 | 24.74 | 170 | 440 | 19 | ||

| 17°32′34″N 120°31′13″E / 17.5427°N 120.5203°E | San Quintin | 2.3% | 5,705 | 5,438 | +0.92% | 66.59 | 25.71 | 86 | 220 | 6 | ||

| 17°36′59″N 120°39′19″E / 17.6165°N 120.6553°E | Tayum | 5.9% | 14,869 | 14,467 | +0.52% | 55.68 | 21.50 | 270 | 700 | 11 | ||

| 17°46′58″N 120°56′38″E / 17.7828°N 120.9439°E | Tineg | 2.0% | 4,977 | 5,097 | −0.45% | 744.80 | 287.57 | 6.7 | 17 | 10 | ||

| 17°15′24″N 120°43′32″E / 17.2567°N 120.7256°E | Tubo | 2.3% | 5,674 | 5,699 | −0.08% | 492.12 | 190.01 | 12 | 31 | 10 | ||

| 17°26′16″N 120°37′31″E / 17.4379°N 120.6253°E | Villaviciosa | 2.3% | 5,675 | 5,392 | +0.98% | 102.93 | 39.74 | 55 | 140 | 8 | ||

| Total | 250,985 | 241,160 | +0.76% | 4,199.72 | 1,608.21 | 60 | 160 | 303 | ||||

| † Provincial capital | Municipality | |||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

Barangays

[edit]The 27 municipalities of the province comprise a total of 303 barangays, with Poblacion in La Paz as the most populous in 2010, and Pattaoig in San Juan as the least.[27][25]

Demographics

[edit]The population of Abra in the 2020 census was 250,985 people,[6] with a density of 60 inhabitants per square kilometre or 160 inhabitants per square mile.

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1903 | 51,860 | — |

| 1918 | 72,731 | +2.28% |

| 1939 | 87,780 | +0.90% |

| 1948 | 86,600 | −0.15% |

| 1960 | 115,193 | +2.41% |

| 1970 | 145,508 | +2.36% |

| 1975 | 147,010 | +0.21% |

| 1980 | 160,198 | +1.73% |

| 1990 | 184,743 | +1.44% |

| 1995 | 195,964 | +1.11% |

| 2000 | 209,491 | +1.44% |

| 2007 | 230,953 | +1.35% |

| 2010 | 234,733 | +0.59% |

| 2015 | 241,160 | +0.52% |

| 2020 | 250,985 | +0.79% |

| Source: PSA[26][27][28] | ||

Abra's inhabitants are mostly descendants of Ilocano settlers and members of the Tingguian tribe. Based on 2000 census data, Ilocanos comprised 71.94% (150,457) of the total provincial population of 209,146. Tingguians came in second at 18.7% (39,115), while other ethnic groups in the province were the Ibanag at 4.46% (9,334), Itneg at 3.17% (6,624), and Tagalog at 0.42% (869).[29]

Languages

[edit]The predominant languages of Abra are Ilocano[30] and Itneg.[31]

Economy

[edit]As of 1990 there were 743 cottage industries in Abra of which 208 are registered with the Department of Trade and Industry. 59% are engaged in bamboo and rattan craft making, both leading industries in the area.

Abra's economy is agriculture-based. Its major crops are rice, vegetables and root crops. Commercial products include coffee, tobacco and coconut. Extensive grassland and pasture areas are used for livestock production.

Sports

[edit]The province's lone professional sports team is the Abra Weavers of the Maharlika Pilipinas Basketball League (MPBL). The Weavers joined the league in the 2024 season.[40]

Infrastructure

[edit]Power distribution

[edit]Government

[edit]List of former military and elected governors:[41]

- Don Ramon Tajonera y Marzal (Military Governor): 1846–1852

- Don Esteban de Penarrubia (Military Governor): 1868–?

- Col. William Bowen (Military Governor): 1901

- Juan G. Villamor (Governor): 1902–1904

- Joaquin J. Ortega (Governor): 1904–1914

- Rosalio G. Eduarte (Governor): 1914–1916

- Julio V. Borbon (Governor): 1916–1922

- Virgilio V. Valera (Governor): 1922–1925

- Eustaquio P. Purugganan (Governor): 1925–1930

- Virgilio V. Valera (Governor): 1930–1936

- Bienvenido N. Valera (Governor): 1936–1939

- Eustaquio P. Purugganan (Governor): 1939–1941

- Bernardo V. Bayquen (Governor): 1941–1944

- Zacarias A. Crispin (Governor): 1944–1946

- Juan C. Brillantes (Governor): 1946–1947

- Luis F. Bersamin (Governor): 1947–1951

- Lucas P. Paredes (Governor): 1951–1953

- Vene B. Pe Benito was acting governor in 1953

- Ernesto P. Parel (Governor): 1953–1954

- Jose L. Valera (Governor):1954–1963

- Carmelo Z. Barbero (Governor): 1963–1965

- Petronilo V. Seares (Governor): 1965–1971

- Gabino V. Balbin (Governor): 1971–1977

- Arturo V. Barbero (Governor): 1977–1984

- Andres B. Bernos (Governor): 1984–1986

- Vicente P. Valera (Governor): 1986–1987

- Buenaventura V. Buenafe was acting governor in 1987

- Vicente Y. Valera (Governor): 1988–1998

- Constante B. Culangen was acting governor in 1998

- Maria Zita Claustro-Valera (Governor): 1998–2001

- Vicente Y. Valera (Governor): 2001–2007

- Eustaquio P. Bersamin (Governor): 2007–2016

- Maria Jocelyn Valera Bernos (Governor): 2016–2022

- Dominic B. Valera (Governor): 2022–present

Notable people

[edit]- Kurt Bryan Barbosa – SEA Games gold medallist, Taekwondo proud waving carry the Filipino flag

- Pura Sumangil – community activist

- Myrna Toribio Esguerra – crowned Binibining Pilipinas International 2024 from Pidigan

Notes

[edit]- ^ Suspended since December 9, 2024[1]

- ^ However, a court in Abra issued a 20-day temporary restraining order against the suspension order on September 2, which lapsed on September 23.

- ^ Suspended since August 12, 2024, was declared final and executory by the DESLA, Office of the President of the Philippines[3][4]

References

[edit]- ^ Dumlao, Artemio (December 10, 2024). "Palace suspends Abra Governor for 60 days". The Philippine Star. Retrieved December 16, 2024.

- ^ "Court stops Malacañang's suspension of Abra vice governor". Rappler. September 6, 2024. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ Quitasol, Aldwin (September 30, 2024). "Abra vice governor suspension final, says OP". Daily Tribune. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ "Malacañang suspends Abra vice governor over COVID-19 hospital lockdown order". Rappler. August 23, 2024. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ "List of Provinces". PSGC Interactive. Makati, Philippines: National Statistical Coordination Board. Archived from the original on April 19, 2016. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c Census of Population (2020). "Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR)". Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ "The Ilocos Review Volume 19 - 1987". The Ilocos Review. Arnoldus Press, Inc. ISSN 0019-2538.

- ^ "Act No. 2683; An Act to Authorize the Segregation of the Subprovince of Abra from the Province of Ilocos Sur and the Reestablishment of the Former Province of Abra, and for Other Purposes". Supreme Court E-Library. March 9, 1917. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- ^ Robles, Raissa (2016). Marcos Martial Law: Never Again. Filipinos for a Better Philippines, Inc.

- ^ Balbosa, Joven Zamoras (1992). "IMF Stabilization Program and Economic Growth: The Case of the Philippines" (PDF). Journal of Philippine Development. XIX (35). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 21, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ Balisacan, A. M.; Hill, Hal (2003). The Philippine Economy: Development, Policies, and Challenges. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195158984.

- ^ Cororaton, Cesar B. "Exchange Rate Movements in the Philippines". DPIDS Discussion Paper Series 97-05: 3, 19.

- ^ Kessler, Richard J. (1989). Rebellion and repression in the Philippines. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300044062. OCLC 19266663.

- ^ Celoza, Albert F. (1997). Ferdinand Marcos and the Philippines: The Political Economy of Authoritarianism. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780275941376.

- ^ Schirmer, Daniel B. (1987). The Philippines reader : a history of colonialism, neocolonialism, dictatorship, and resistance (1st ed.). Boston: South End Press. ISBN 0896082768. OCLC 14214735.

- ^ Magno, Alexander R., ed. (1998). "Democracy at the Crossroads". Kasaysayan, The Story of the Filipino People Volume 9:A Nation Reborn. Hong Kong: Asia Publishing Company Limited.

- ^ "Alfred McCoy, Dark Legacy: Human rights under the Marcos regime". Ateneo de Manila University. September 20, 1999.

- ^ Abinales, P.N.; Amoroso, Donna J. (2005). State and society in the Philippines. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0742510234. OCLC 57452454.

- ^ "Gone too soon: 7 youth leaders killed under Martial Law". Rappler. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ Pawilen, Reidan M. (May 2021). "The Solid North myth: an Investigation on the status of dissent and human rights during the Marcos Regime in Regions 1 and 2, 1969-1986". University of the Philippines Los Baños University Knowledge Digital Repository. Archived from the original on November 13, 2021. Retrieved May 22, 2022.

- ^ a b DALANG, RHODA; DACPANO, BRENDA S. (April 10, 2016). "Terror reigns in Abra, revisited". nordis.net.

- ^ "Executive Order No. 220; Creating a Cordillera Administrative Region, Appropriating Funds Therefor and for Other Purposes". The LawPhil Project. Manila, Philippines. July 15, 1987. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

Sec. 2. Territorial Coverage. For purposes of the CAR, the region shall consist of the provinces of Abra, Benguet, Ifugao, Kalinga-Apayao and Mt. Province and the chartered city of Baguio. Until otherwise provided by the Cordillera Executive Board (CEB), the seat of the CAR shall be Baguio City.

- ^ Situational Report No. 15 for Magnitude 7 Earthquake in Tayum, Abra (2022) (PDF) (Report). National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council. August 10, 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- ^ "Situational Report for Magnitude 6.4 Earthquake in Lagayan, Abra (2022)" (PDF). National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council.

- ^ a b c d "Province: Abra (province)". PSGC Interactive. Quezon City, Philippines: Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- ^ a b Census of Population (2015). "Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR)". Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ^ a b Census of Population and Housing (2010). "Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR)" (PDF). Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. National Statistics Office. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ Census of Population and Housing (2010). Population and Annual Growth Rates for The Philippines and Its Regions, Provinces, and Highly Urbanized Cities (PDF). National Statistics Office. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ a b "Abra: Housing Unit Occupancy Rate Nears 100%; Table 5. Household Population by Ethnicity and Sex: Abra, 2000". Philippine Statistics Authority. April 3, 2002. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved December 4, 2015.

- ^ Dalby, Andrew (February 18, 2004). Dictionary of Languages: The Definitive Reference to More Than 400 Languages. Columbia University Press. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-231-11569-8.

- ^ Tryon, Darrell T. (1994). Comparative Austronesian Dictionary: An Introduction to Austronesian Studies. Ratzlow-Druck. p. 171. ISBN 3-11-012729-6.

- ^ "Poverty incidence (PI):". Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ "Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. November 29, 2005.

- ^ "2009 Official Poverty Statistics of the Philippines" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. February 8, 2011.

- ^ "Annual Per Capita Poverty Threshold, Poverty Incidence and Magnitude of Poor Population, by Region and Province: 1991, 2006, 2009, 2012 and 2015". Philippine Statistics Authority. August 27, 2016.

- ^ "Annual Per Capita Poverty Threshold, Poverty Incidence and Magnitude of Poor Population, by Region and Province: 1991, 2006, 2009, 2012 and 2015". Philippine Statistics Authority. August 27, 2016.

- ^ "Annual Per Capita Poverty Threshold, Poverty Incidence and Magnitude of Poor Population, by Region and Province: 1991, 2006, 2009, 2012 and 2015". Philippine Statistics Authority. August 27, 2016.

- ^ "Updated Annual Per Capita Poverty Threshold, Poverty Incidence and Magnitude of Poor Population with Measures of Precision, by Region and Province: 2015 and 2018". Philippine Statistics Authority. June 4, 2020.

- ^ "2021 Full Year Official Poverty Statistics of the Philippines" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. August 15, 2022. Retrieved April 28, 2024.

- ^ "MPBL welcomes unlimited pros, expands with two new franchises". Tiebreaker Times. February 6, 2024. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ Gaioni, SVD, Fr. Dominic T., Historical Highlights of the Province of Abra From 1585 to 1920

External links

[edit] Media related to Abra (province) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Abra (province) at Wikimedia Commons Geographic data related to Abra (province) at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Abra (province) at OpenStreetMap- History articles and links on Bucay and Abra