Abergavenny

Abergavenny

| |

|---|---|

The clock tower of Abergavenny Town Hall, Cross Street | |

Location within Monmouthshire | |

| Population | 13,695 (2021) [1] |

| OS grid reference | SO295145 |

| Community |

|

| Principal area | |

| Preserved county | |

| Country | Wales |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | ABERGAVENNY |

| Postcode district | NP7 |

| Dialling code | 01873 |

| Police | Gwent |

| Fire | South Wales |

| Ambulance | Welsh |

| UK Parliament | |

| Senedd Cymru – Welsh Parliament | |

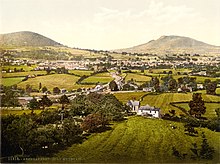

Abergavenny (/ˌæbərɡəˈvɛni/; Welsh: Y Fenni, pronounced [ə ˈvɛnɪ], archaically Abergafenni, 'mouth of the River Gavenny') is a market town and community in Monmouthshire, Wales. Abergavenny is promoted as a "Gateway to Wales"; it is approximately 6 miles (10 km) from the border with England and is located where the A40 trunk road and the recently upgraded A465 Heads of the Valleys road meet.[2][3]

Originally the site of a Roman fort, Gobannium, it became a medieval walled town within the Welsh Marches. The town contains the remains of a medieval stone castle built soon after the Norman conquest of Wales.

Abergavenny is situated at the confluence of the River Usk and a tributary stream, the Gavenny.[4] It is almost entirely surrounded by mountains and hills: the Blorenge (559 m, 1,834 ft),[5] the Sugar Loaf (596 m, 1,955 ft), Skirrid Fawr (Great Skirrid), Ysgyryd Fach (Little Skirrid), Deri, Rholben and Mynydd Llanwenarth, known locally as "Llanwenarth Breast". Abergavenny provides access to the nearby Black Mountains and the wider Brecon Beacons National Park. The Cambrian Way, Beacons Way and Marches Way pass through Abergavenny whilst the Offa's Dyke Path passes through Pandy five miles to the north and the Usk Valley Walk passes through nearby Llanfoist.

In the UK 2011 census, the six relevant wards (Lansdown, Grofield, Castle, Croesonen, Cantref and Priory) collectively listed Abergavenny's population as 12,515. The town hosted the 2016 National Eisteddfod of Wales.

Etymology

[edit]The town derives its name from a Brythonic word Gobannia meaning "river of the blacksmiths", and relates to the town's pre-Roman importance in iron smelting. The name is related to the modern Welsh word gof (blacksmith), and so is also associated with the Welsh smith Gofannon from folklore. The river later became, in Welsh, Gafenni, and the town's name became Abergafenni, meaning "mouth of (Welsh: Aber) the Gavenny (Gafenni)". In Welsh, the shortened form Y Fenni may have come into use after about the 15th century, and is now used as the Welsh name. Abergavenny, the English spelling, is in general use.[6]

Geography

[edit]The town originally developed on the high ground to the north of the floodplain of the River Usk and to the west of the valley of the much smaller Gavenny River though has since extended to the east of the latter. It has merged with the originally separate settlement of Mardy to the north but remains separate from that of Llanfoist to the south due to the presence of the river and its floodplain; nevertheless Llanfoist is in many ways a suburb of the town. The ground rises gradually in the north of the town before steepening to form the Deri and Rholben spurs of Sugar Loaf. The A4143 crossing of the Usk by means of the historic Usk Bridge is sited at the narrowest point of the floodplain, a site also chosen for the former crossing of a tramroad and the later mainline railway. The high ground at either side is formed by a legacy of the last ice age, the recessional Llanfoist moraine which underlies both the village which gives it its name, the town centre and the Nevill Hall area. The older parts of the town north of its centre are built upon a relatively flat-lying alluvial fan extending west from the area of St Mary's Priory to Cantref and of similar age to the moraine.[7]

In the UK 2011 census, the six relevant wards (Lansdown, Grofield, Castle, Croesonen, Cantref and Priory) collectively listed Abergavenny's population as 12,515.[8][9][10][11][12][13]

History

[edit]Roman period

[edit]Gobannium was a Roman fort guarding the road along the valley of the River Usk,[4] which linked the legionary fortress of Burrium (Usk) and later Isca Augusta or Isca Silurum (Caerleon) in the south with Y Gaer, Brecon and Mid Wales. It was also built to keep the peace among the local British Iron Age tribe, the Silures.[14] Cadw considers that the fort was occupied from around CE50 to CE150.[15] Remains of the walls of this fort were discovered west of the castle when excavating the foundations for a new post office and telephone exchange building in the late 1960s.[16]

11th century

[edit]

Abergavenny grew as a town in early Norman times under the protection of the Baron Bergavenny (or Abergavenny). The first Baron was Hamelin de Balun, from Ballon, a small town with a castle in Maine-Anjou near Le Mans. Today it is in the Sarthe département of France. He founded the Benedictine priory, now the Priory Church of St Mary, in the late 11th century. The Priory belonged originally to the Benedictine foundation of St. Vincent Abbaye at Le Mans. It was subsequently endowed by William de Braose, with a tithe of the profits of the castle and town.[17] The church contains some unique alabaster effigies, church monuments and unique medieval wood carving, such as the Tree of Jesse.[18]

12th and 13th centuries

[edit]Owing to its geographical location, the town was frequently embroiled in the border warfare and power play of the 12th and 13th centuries in the Welsh Marches. In 1175, Abergavenny Castle was the site of a massacre of Seisyll ap Dyfnwal and his associates by William de Braose, 4th Lord of Bramber.[19] Reference to a market at Abergavenny is found in a charter granted to the Prior by William de Braose.[17]

15th to 17th centuries

[edit]

Owain Glyndŵr attacked Abergavenny in 1404. According to popular legend, his raiders gained access to the walled town with the aid of a local woman who sympathised with the rebellion, letting a small party in via the Market Street gate at midnight. They were able to open the gate and allow a much larger party who set fire to the town and plundered its churches and homes leaving Abergavenny Castle intact. Market Street has been referred to as "Traitors' Lane" thereafter. In 1404 Abergavenny was declared its own nation by Ieuan ab Owain Glyndŵr, illegitimate son of Owain Glyndŵr. The arrangement lasted approximately two weeks.[20][21]

At the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1541, the priory's endowment went towards the foundation of a free grammar school, King Henry VIII Grammar School, the site itself passing to the Gunter family.[17] During the Civil War, prior to the siege of Raglan Castle in 1645, King Charles I visited Abergavenny and presided in person over the trial of Sir Trefor Williams, 1st Baronet of Llangibby, a Royalist who changed sides, and other Parliamentarians.[17] In 1639, Abergavenny received a charter of incorporation under the title of bailiff and burgesses. A charter with extended privileges was drafted in 1657, but appears never to have been enrolled or to have come into effect. Owing to the refusal of the chief officers of the corporation to take the oath of allegiance to William III in 1688, the charter was annulled, and the town subsequently declined in prosperity. Chapter 28 of the 1535 Act of Henry VIII, which provided that Monmouth, as county town, should return one burgess to Parliament, further stated that other ancient Monmouthshire boroughs were to contribute towards the payment of the member. In consequence of this clause Abergavenny on various occasions shared in the election, the last instance being in 1685.[17]

The right to hold two weekly markets and three yearly fairs, beginning in the 13th century, was held ever since as confirmed in 1657.[22] Abergavenny was celebrated for the production of Welsh flannel, and also for the manufacture, whilst the fashion prevailed, of goats' hair periwigs.[17]

19th and 20th centuries

[edit]

Abergavenny railway station, situated southeast of the town centre, opened on 2 January 1854 as part of the Newport, Abergavenny and Hereford Railway. The London North Western Railway sponsored the construction of the railway linking Newport station to Hereford station. The line was taken over by the West Midland Railway in 1860 before becoming part of the Great Western Railway in 1863. A railway line also ran up the valley towards Brynmawr and to Merthyr Tydfil; this was closed during the Beeching cuts in the 1960s and the line to Clydach Gorge is now a cycle track and footpath. The Baker Street drill hall was completed in 1896.[23] Adolf Hitler's deputy, Rudolf Hess, was kept under escort at Maindiff Court Hospital during the Second World War, after his flight to Britain.[24] In 1964, the Royal Observer Corps opened a small monitoring bunker to be used in the event of a nuclear attack. It was closed in 1968 but reopened in 1973 due to the closure of a bunker near Brynmawr. It closed in 1991 on the stand down of the ROC. It remains mostly intact.[25]

Baron of Abergavenny

[edit]The title of Baron Abergavenny was first held by the Beauchamp family. In the late 14th century the reversion of the feudal marcher barony (with the castle, town and surrounding lands appurtenant) was purchased from John Hastings, 3rd Earl of Pembroke, who had no heirs, by William Beauchamp, the second son of the Earl of Warwick; and he was elevated to the House of Lords as Baron Bergavenny. On his death, his wife Joan held the entire barony in survivorship for life until 1435, at which time it passed into the Nevill family; Joan's granddaughter Elizabeth, heir to the barony, married a Neville, Edward Nevill, 3rd Baron Bergavenny.[26] From him it has descended continuously, the title being increased to an earldom in 1784; and in 1876 William Nevill [sic] 5th Earl, an indefatigable and powerful supporter of the Conservative Party, was created 1st Marquess of Abergavenny.[17]

Coldbrook Park was a country house in an estate some 1+1⁄4 miles (2 km) southeast of the town. The house was originally built in the 14th century and belonged to the Herbert family for many generations until purchased by John Hanbury for his son, the diplomat Sir Charles Hanbury Williams.[27] Sir Charles reconstructed the house in 1746 with the addition of a nine-bay two-storey Georgian façade with a Doric portico. It was subsequently passed down in the Hanbury Williams family until it was demolished in 1954.[28]

Events

[edit]Held during the first week of August every year, the National Eisteddfod is a celebration of the culture and language in Wales. The festival travels from place to place, alternating between north and south Wales, attracting around 150,000 visitors and over 250 tradestands and stalls. In 2016 it was held in Abergavenny for the first time since 1913. The Chair and Crown for 2016 were presented to the festival's Executive Committee at a ceremony held in Monmouth on 14 June 2016.[29]

The Abergavenny Food Festival is held in the second week of September each year. The Steam, Veteran and Vintage Rally takes place in May every year. The event expands year on year with the 2016 rally including a rock choir, shire horses, motorcycling stunts, vintage cars and steam engines.[30] The Country and Western Music Festival is attended by enthusiasts of country music. It marked its third year in 2016 and was attended by acts including Ben Thompson, LA Country and many more. The event was last held in 2017.[31][32] The Abergavenny Writing Festival began in April 2016 and is a celebration of writing and the written word.[33] The Abergavenny Arts Festival, first held in 2018, celebrates arts in their broadest sense and showcases amateur and professional artists from the vibrant local arts scene together with some from further afield.[34]

Welsh language

[edit]In recent decades the number of Welsh speakers in the town has increased dramatically. The 2001 census recorded that 10% of the local population spoke the language, a five-fold increase over ten years from the figure of 2% recorded in 1991.[35] The town has one of the two Welsh-medium primary schools in Monmouthshire, Ysgol Gymraeg y Fenni,[36] which was founded in the early 1990s. It is also home to the Abergavenny Welsh society, Cymreigyddion y Fenni,[37] and the local Abergavenny Eisteddfod.[38]

Sport

[edit]Abergavenny was the home of Abergavenny Thursdays F.C., formed in 1927 and merged with Govilon, the local village side in 2013. The new club, Abergavenny Town F.C., plays at the Pen-y-pound Stadium, maintained and run by Thursday’s football trust, as members of the Ardal South East league (tier 3) for the 2021–22 season. It is also the home of Abergavenny RFC, a rugby union club founded in 1875 that plays at Bailey Park, Abergavenny. In the 2018–19 season, they play in the Welsh Rugby Union Division Three East A league.[39] Abergavenny Hockey Club, formed in 1897, currently play at the Abergavenny Leisure Centre on Old Hereford Road.[40]

Abergavenny Cricket Club play at Pen-y-Pound, Avenue Road and Glamorgan CCC also play some of their games here. Abergavenny Cricket Club was founded in 1834 and celebrated the 175th anniversary of its foundation in 2009.[41] Abergavenny Tennis Club also play at Pen-y-Pound and plays in the South Wales Doubles League and Aegon Team Tennis. The club engages the services of a head tennis professional to run a coaching programme for the town and was crowned Tennis Wales' Club of the Year in 2010.[42] Abergavenny hosted the British National Cycling Championships in 2007, 2009 and 2014, as part of the town's Festival of Cycling.[43]

Cattle market

[edit]A cattle market was held in Abergavenny from 1863 to December 2013.[4][44] From 1825 to 1863 a sheep market was held at a site in Castle Street, to stop the sale of sheep on the streets of the town. When the market closed, the site was leased and operated by Abergavenny Market Auctioneers Ltd, who held regular livestock auctions on the site. Market days were held on Tuesdays for the auction sale of finished sheep, cull ewe/store and fodder (hay and straw), and on some Fridays for the auction sale of cattle. After Newport's cattle market closed in 2009 for redevelopment, Newport's sales were held at Abergavenny every Wednesday.[45]

In 2011 doubts about the future of Abergavenny Cattle Market were raised after Monmouthshire County Council granted planning permission for its demolition and replacement with a supermarket, car park, and library.[46] In January 2012 the Welsh Government announced the repeal of the Abergavenny Improvement Acts of 1854 to 1871 which obliged the holding of a livestock market within the boundaries of Abergavenny town;[47] that repeal being effective from 26 March 2012.[48] The county council, which requested that the Abergavenny Improvement Acts be repealed, supported plans for a new cattle market to be established about 10 miles (16 km) from Abergavenny in countryside at Bryngwyn, some 3 miles (5 km) from Raglan. There was local opposition to this site.[49][50][51] The new Monmouthshire Livestock Centre, a 27-acre site at Bryngwyn, opened in November 2013.[52]

Culture

[edit]Cultural history

[edit]Abergavenny has hosted the National Eisteddfod of Wales in 1838, 1913 and most recently in 2016. In 2017 the town was named one of the best places to live in Wales.[53][54] The town's local radio stations are currently[when?] Sunshine Radio 107.8 FM and NH Sound 1287 AM. Abergavenny is home to an award-winning brass band.[55] Formed in Abergavenny prior to 1884,[56] the band were joint National Welsh League Champions in 2006[57] and joint National Welsh League Champions in 2011.[58] The band also operates a Junior Band training local young musicians.

The Borough Theatre in Abergavenny town centre hosts live events covering drama, opera, ballet, music, children's events, dance, comedy, storytelling, tribute bands and talks.[59] The Melville Centre is close to the town centre and includes the Melville Theatre, which hosts a range of live events.[60] The town held its first Abergavenny Arts Festival in 2018[61] and also hosts the Abergavenny Food Festival in September each year.[62]

In popular culture

[edit]William Shakespeare's play Henry VIII features the character Lord Abergavenny. In 1968 "Abergavenny" was the title of a UK single by Marty Wilde. In 1969, it was also released in the US, under a Marty Wilde pseudonym Shannon, where it was also a minor hit.[63] In The Adventure of the Priory School Sherlock Holmes refers to a case he is working on in Abergavenny.[64] Abergavenny is mentioned by Stan Shunpike, the conductor of the Knight Bus when the bus takes a detour there to drop off a passenger in J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. The TV series Upstairs, Downstairs, features a character in the second season, Thomas Watkins, the devious Bellamy family chauffeur, who comes from Abergavenny. In the 1979 spinoff of Upstairs, Downstairs titled Thomas & Sarah, Watkins and Sarah Moffat, another major character, marry and return briefly to Abergavenny. * Much of the 1996 film, Intimate Relations starring Julie Walters, Rupert Graves, Les Dennis and Amanda Holden, was filmed at many locations in and around Abergavenny.

Transport

[edit]Railway

[edit]Abergavenny railway station lies on the Welsh Marches Line from Newport to Hereford. The weekday daytime service pattern typically sees one train per hour in each direction between Manchester Piccadilly and Cardiff Central, with most trains continuing beyond Cardiff to Swansea and west Wales. There is also a two-hourly service between Cardiff and the North Wales Coast Line to Holyhead, via Wrexham General. These services are all operated by Transport for Wales.[65]

Roads

[edit]The town is located where the A40 trunk road and the A465 Heads of the Valleys road meet. The latter used to meet the A40 in the town centre but the A465 now runs to the east of the town centre.

Buses

[edit]A network of services link the town with local villages. In addition Stagecoach South Wales operate service 23 to Hereford and Newport approximately every two hours while Newport Bus operates service 83 to Monmouth.

Notable buildings

[edit]

Abergavenny Castle is located strategically just south of the town centre overlooking the River Usk. It was built in about 1067 by the Norman baron Hamelin de Ballon to guard against incursions by the Welsh from the hills to the north and west. All that remains is defensive ditches and the ruins of the stone keep, towers, and part of the curtain wall. It is a Grade I listed building.[66]

Various markets are held in the Market Hall, for example: Tuesdays, Fridays and Saturdays – retail market; Wednesdays – flea market; fourth Thursday of each month – farmers' market; third Sunday of each month – antique fair; second Saturday of each month – craft fair.[67]

The Church in Wales church of the Holy Trinity is in the Diocese of Monmouth. Holy Trinity Church was consecrated by the Bishop of Llandaff on 6 November 1840. It was originally built as a chapel to serve the adjacent almshouses and the nearby school. It has been Grade II listed since January 1974.

Other listed buildings in the town include the parish Priory Church of St Mary, a medieval and Victorian building that was originally the church of the Benedictine priory founded in Abergavenny before 1100; the sixteenth century Tithe Barn near St Mary's; the Victorian Church of the Holy Trinity; the Grade II* listed St John's Masonic Lodge; Abergavenny Museum; the Public Library; the Town Hall; and the remains of Abergavenny town walls behind Neville Street.[68]

From 1851, the Monmouthshire lunatic asylum, later Pen-y-Fal Hospital, a psychiatric hospital, stood on the outskirts of Abergavenny. Between 1851 and 1950, over 3,000 patients died at the hospital. A memorial plaque for the deceased has now been placed at the site. After its closure in the 1990s, its buildings and grounds were redeveloped as housing.[69] Some psychiatric services are now administered from Maindiff Court Hospital on the outskirts of the town, close to the foot of the Skirrid mountain.

Parks and gardens

[edit]Abergavenny has three public urban parks which are listed on the Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in Wales: the grounds of Abergavenny Castle,[70] Linda Vista Gardens[71] and Bailey Park.[72] A fourth registered garden, at The Hill to the north of the town, forms part of the grounds of a residential development.[73]

Twinning

[edit]Abergavenny is twinned with:

Military

[edit]One of the eleven Victoria Cross medals won at Rorke's Drift was awarded to John Fielding from Abergavenny. He had enlisted under the false name of Williams. One was also awarded for the same action to Robert Jones, born at Clytha between Abergavenny and Raglan. Another Abergavenny-born soldier, Thomas Monaghan received his VC for defending his colonel during the Indian Rebellion. In 1908 following the formation of the Territorial Force the Abergavenny Cadet Corps was formed and affiliated with the 3rd Battalion, The Monmouthshire Regiment. In 1912 the regiment was affiliated with the new formed 1st Cadet Battalion, The Monmouthshire Regiment.[75]

Notable people

[edit]See also Category:People from Abergavenny

- Augustine Baker (1575–1641), well-known Benedictine mystic and an ascetic writer. He was one of the earliest members of the English Benedictine Congregation which was newly restored to England after the Reformation.

- John Williams (1857–1932) soldier, recipient of the Victoria Cross for actions at Rorke’s Drift.

- Scott Ellaway (born 1981), conductor, was born and brought up locally.

- Becky James (born 1991), racing cyclist, double gold medallist at the 2013 UCI Track Cycling World Championships and double silver medallist at the 2016 Summer Olympics, was born and grew up in Abergavenny.

- Matthew Jay (1978–2003), singer-songwriter, spent much of his life in the town.

- Peter Law (1948–2006), politician and Independent MP, notable for defeating the Labour candidate in the safest Welsh seat during the 2005 general election was born in Abergavenny.[76]

- Saint David Lewis (1616–1679), Catholic priest and martyr, was born in Abergavenny and prayed in the local Gunter Mansion.

- Malcolm Nash (1945–2019), cricketer, famous for bowling to Gary Sobers who hit six sixes in one Nash over, was born in Abergavenny.

- Mary Penry (1735–1804), Moravian sister in 18th-century Pennsylvania was born in Abergavenny.

- Owen Sheers (born 1974), poet, grew up in Abergavenny.

- Oliver Thornton (born 1979), West End actor, starred of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, was born and grew up in Abergavenny.

- Vulcana (Miriam Kate Williams, 1874–1946), world-famous strongwoman, was born in Abergavenny.

- Ethel Lina White (1876–1944), crime writer best known for her novel The Wheel Spins (1936), on which the Alfred Hitchcock film The Lady Vanishes (1938) was based.

- Jules Williams (born 1968), writer, director, and producer of The Weigh Forward.[77]

- Raymond Williams, (1921–1988) academic, critic and writer was born and brought up locally.

- Dave Richards, (1993) professional footballer for Crewe Alexandra was born and raised in the town.

- Marina Diamandis (1985), professional singer and songwriter

See also

[edit]- Abergavenny Castle

- Abergavenny Chronicle

- Abergavenny fireworks display

- Abergavenny Hundred

- Abergavenny Museum

- Abergavenny town walls

- Black Mountains, Wales

- Brecon Beacons National Park

- HMS Abergavenny, a fourth-rate ship acquired by the Royal Navy in 1795.

- Llanthony Priory

- Monmouthshire & Brecon Canal

- Nevill Hall Hospital

- The Skirrid Mountain Inn at Llanvihangel Crucorney, maybe Wales' oldest pub

- Tourism in Wales

- Y Graig

References

[edit]- ^ Within the dataset under 1d."Towns and cities, characteristics of built-up areas, England and Wales: Census 2021". 2 August 2023. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

- ^ BBC. "The Gateway to Wales". Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ^ Frommers. "Introduction to Abergavenny". Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ^ a b c Hoiberg, Dale H., ed. (2010). "Abergavenny". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. I: A-ak Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, IL: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. pp. 29. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- ^ Geograph British Isles – The Blorenge from the B4598 road at Ty'r-pwll

- ^ Hywel Wyn Owen, The Place-Names of Wales, 1998, ISBN 0-7083-1458-9

- ^ "sheet 232 Abergavenny (solid and drift geology)". Maps Portal. British Geological Survey. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Services, Good Stuff IT. "Lansdown – UK Census Data 2011". UK Census Data. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ Services, Good Stuff IT. "Grofield – UK Census Data 2011". UK Census Data. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ Services, Good Stuff IT. "Castle – UK Census Data 2011". UK Census Data. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ Services, Good Stuff IT. "Croesonen – UK Census Data 2011". UK Census Data. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ Services, Good Stuff IT. "Cantref – UK Census Data 2011". UK Census Data. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ Services, Good Stuff IT. "Priory – UK Census Data 2011". UK Census Data. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ Haverfield, Francis John (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 109.

- ^ Cadw. "Abergavenny Roman Fort (MM193)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ "Flannel Street | Abergavenny Local History Society Street Survey". abergavennystreetsurvey.co.uk. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Abergavenny". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 53.

- ^ "HISTORIC MONUMENTS AT ST MARY'S PARISH CHURCH: St Mary's Priory, Abergavenny". stmarys-priory.org. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ Carradice, Phil (9 December 2013). "Treachery, stealth and slaughter at Abergavenny Castle". BBC blogs.

- ^ Butters, Tim (2017). Secret Abergavenny. Stroud. ISBN 978-1-4456-6689-1. OCLC 987583154.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Owain Glyndwr in Abergavenny". Abergavenny Now. 3 May 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh (1922). Encyclopaedia Britannica:a Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature, and General Information (11 ed.). New York: Encyclopaedia Britannica. p. 53.

- ^ "Abergavenny". The Drill Hall Project. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ BBC. WW2 People's War – Marjorie's War

- ^ "Abergavenny ROC Post – Subterranea Britannica". www.subbrit.org.uk. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Pugh, T.B. (2004). "Neville, Edward, first Baron Bergavenny (d. 1476), nobleman". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online) (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/19929. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ An Historical Tour in Monmouthshire. Vol. 2. p. 270.

- ^ "COLDBROOK HOUSE (DEMOLISHED)". Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Sites of Wales. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ^ "Crown and Chair Presented to the Eisteddfod Committee – Abergavenny Now". abergavennynow.com. 14 June 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ "Abergavenny Steam Rally 2016 – Abergavenny Now". abergavennynow.com. 26 May 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ "Abergavenny Country & Western Music Festival 2016". abergavennynow.com. 26 April 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ "Abergavenny Country & Western Music Festival". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ "What's on at the Abergavenny Writing Festival? – Abergavenny Now". abergavennynow.com. 9 April 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ "Abergavenny Arts Festival 29th & 30th June 2019". Abergavenny Arts Festival. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ "Abergavenny Welsh speakers eager to promote language". Archived from the original on 21 November 2008.

- ^ "Ysgol Gymraeg y Fenni". ysgolgymraegyfenni.co.uk. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ "Cymreigyddion y Fenni". Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ "Abergavenny Eisteddfod". Archived from the original on 22 July 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ "Abergavenny RFC". Abergavenny RFC. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ "Abergavenny Hockey Club". Abergavenny Hockey Club. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ "Abergavenny Cricket". abergavennycricket.co.uk. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ "Abergavenny Tennis Club". Abergavenny Tennis Club. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ Howell, Andy (4 October 2013). "Abergavenny wins bid to stage 2014 British Road Race". WalesOnline. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ "End of an era as Abergavenny's livestock market closes". South Wales Argus. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ "Newport cattle market finds new home". South Wales Argus. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ Minutes of the Planning Committee held at County Hall, Cwmbran on 14 June 2011 Archived 24 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "BBC News, Law change spells end for Abergavenny cattle market, 12 January 2012". BBC News. 12 January 2012.

- ^ "The Abergavenny Improvement Act 1854 (Repeal) Order 2012". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ "Objections raised to cattle market plan". South Wales Argus. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ "Cattle market campaigners set for legal action". South Wales Argus. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ "Auctioneers speak out". Abergavenny Chronicle. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ "New £5m Raglan cattle market opens". South Wales Argus. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ "These towns have been named as the best places to live in Wales". Wales Online. 10 March 2017.

- ^ Sands, Katie (10 March 2017). "These towns have been named as the best places to live in Wales". WalesOnline.

- ^ "Welcome to Abergavenny Borough Brass Band". abergavennyboroughband.org.uk. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ "History of Abergavenny Borough Brass Band in South Wales". abergavennyboroughband.org.uk. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ "Archived News 2006 at Abergavenny Borough Band". abergavennyboroughband.org.uk. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ "Current News at Abergavenny Borough Band". abergavennyboroughband.org.uk. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ "The Borough Theatre - live entertainment in Abergavenny". Archived from the original on 20 July 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ "Melville Centre-Abergavenny". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ "Abergavenny Arts Festival". Literature Wales. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ Blythman, Joanna (30 March 2008). "Anyone for pudding?". Observer Food Monthly.

- ^ "Shannon – Songs". allbutforgottenoldies.net. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ "Sherlock Holmes – The Adventure of the Priory School Page 02". sherlock-holmes.classic-literature.co.uk. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ GB eNRT December 2015 Edition, Table 131

- ^ Cadw. "Abergavenny Castle ruins (Grade I) (2376)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ "Abergavenny Market Information and Opening Times". abergavennynow.com. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ "Listed Buildings in Abergavenny, Monmouthshire, Wales". British Listed Building. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ "Pen-y-Fal, Psychiatric Hospital; Abergavenny Asylum (31993)". Coflein. RCAHMW. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ Cadw. "Abergavenny Castle Grounds (PGW(Gt)9(MON))". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Cadw. "Linda Vista Gardens (PGW(Gt)59(MON))". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Cadw. "Bailey Park (PGW(Gt)60(MON))". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Cadw. "The Hill, Abergavenny (PGW(Gt)62(MON))". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ a b "Twinning". Abergavenny Town Council. 25 January 2017. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ Westlake, Ray. (2011). The Territorials : 1908–1914 : a guide for military and family historians. Barnsley, South Yorkshire. ISBN 9781848843608. OCLC 780443267.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "BBC NEWS | Wales | Labour challenger Peter Law dies".

- ^ Williams, Jules (2011). The Weigh Forward. Quartet Books. ISBN 978-0-7043-7214-6.

Sources

[edit]- Jürgen Klötgen, Prieuré d'Abergavenny – Tribulations mancelles en Pays de Galles au temps du Pape Jean XXII (d'après des documents français et anglais du XIV° siècle collationnés avec une source d'histoire retrouvée aux Archives Secrètes du Vatican), in Revue Historique et Archéologique du Maine, Le Mans, 1989, p. 65–88 (1319 : cf John of Hastings, Lord of Abergavenny; Adam de Orleton, Bishop of Hereford, John of Monmouth, Bishop of Llandaff).

External links

[edit]- Abergavenny Borough Band

- Abergavenny Museum

- BBC, South East Wales – Feature on Abergavenny

- Geograph British Isles – Photos of Abergavenny and surrounding areas

- Abergavenny Roman Fort