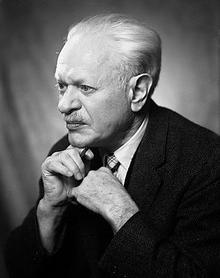

Kenneth Burke

Kenneth Burke | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Kenneth Duva Burke May 5, 1897 Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | November 19, 1993 (aged 96) Andover, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Literary theorist and philosopher |

| Institutions | University of Chicago |

Kenneth Duva Burke (May 5, 1897 – November 19, 1993) was an American literary theorist, as well as poet, essayist, and novelist, who wrote on 20th-century philosophy, aesthetics, criticism, and rhetorical theory.[1] As a literary theorist, Burke was best known for his analyses based on the nature of knowledge. Further, he was one of the first individuals to stray from more traditional rhetoric and view literature as "symbolic action."

Burke was unorthodox, concerning himself not only with literary texts, but also with the elements of the text that interacted with the audience: social, historical, political background, author biography, etc.[2]

For his career, Burke has been praised by The Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory and Criticism as "one of the most unorthodox, challenging, theoretically sophisticated American-born literary critics of the twentieth century." His work continues to be discussed by rhetoricians and philosophers.[3]

Personal history

[edit]Kenneth Duva Burke was born on May 5, 1897 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and graduated from Peabody High School, where he befriended classmates Malcolm Cowley and James Light.[4] He attended Ohio State University to pursue courses in French, German, Greek, and Latin. He moved with his parents to Weehawken, New Jersey and later he enrolled at Columbia University.[5] During his time there, he was a member of the Boar's Head Society.[6] The constraining learning environment, however, impelled Burke to leave Columbia, never receiving a college diploma.[7] In Greenwich Village, he kept company with avant-garde writers such as Hart Crane, Malcolm Cowley, Gorham Munson, and later Allen Tate.[8] Raised by a Christian Science mother, Burke later became an avowed agnostic.

In 1919, he married Lily Mary Batterham, with whom he had three daughters: the late feminist, Marxist anthropologist Eleanor Leacock (1922–1987); musician (Jeanne) Elspeth Chapin Hart (1920-2015); and writer and poet France Burke (born c. 1925). He later divorced Lily and, in 1933, married her sister Elizabeth Batterham, with whom he had two sons, Michael and Anthony. Burke served as the editor of the modernist literary magazine The Dial in 1923, and as its music critic from 1927 to 1929. Kenneth himself was an avid player of the piano. He received the Dial Award in 1928 for distinguished service to American literature. He was the music critic of The Nation from 1934 to 1936, and was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1935.[9]

His work on criticism was a driving force for placing him back into the university spotlight. As a result, he was able to teach and lecture at various colleges, including Bennington College, while continuing his literary work. Many of Burke's personal papers and correspondence are housed at Pennsylvania State University's Special Collections Library. However, despite his stint lecturing at universities, Burke was an autodidact and a self-taught scholar.[10]

In later life, his New Jersey farm was a popular summer retreat for his extended family, as reported by his grandson Harry Chapin, a popular singer-songwriter. Burke died of heart failure at his home in Andover, New Jersey, age 96.[11]

Persuasions and influences

[edit]Burke, like many twentieth-century theorists and critics, was heavily influenced by the ideas of Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, and Friedrich Nietzsche. He was a lifelong interpreter of Shakespeare and was also significantly influenced by Thorstein Veblen. He resisted being pigeonholed as a follower of any philosophical or political school of thought, and had a notable and very public break with the Marxists who dominated the literary criticism set in the 1930s.

Burke corresponded with a number of literary critics, thinkers, and writers over the years, including William Carlos Williams, Malcolm Cowley, Robert Penn Warren, Allen Tate, Ralph Ellison, Albert Murray, Katherine Anne Porter, Jean Toomer, Hart Crane, and Marianne Moore.[12] Later thinkers who have acknowledged Burke's influence include Harold Bloom, Stanley Cavell, J. Hillis Miller, Susan Sontag (his student at the University of Chicago), Erving Goffman,[13] Geoffrey Hartman, Edward Said, René Girard, Fredric Jameson, Michael Calvin McGee, Dell Hymes and Clifford Geertz. Burke was one of the first prominent American critics to appreciate and articulate the importance of Thomas Mann and André Gide; Burke produced the first English translation of "Death in Venice", which first appeared in The Dial in 1924. It is now considered[by whom?] to be much more faithful and explicit than H. T. Lowe-Porter's more famous 1930 translation.

Burke's political engagement is evident—A Grammar of Motives takes as its epigraph, ad bellum purificandum (toward the purification of war).

American literary critic Harold Bloom singled out Burke's Counterstatement and A Rhetoric of Motives for inclusion in his book The Western Canon.

| Part of a series on |

| Rhetoric |

|---|

|

Beyond his contemporary influences, Burke took Aristotle's teachings into account while developing his theories on rhetoric. A significant source of his ideas is Aristotle's Rhetoric. Drawing from this work, Burke oriented his writing about language specifically to its social context. Similarly, he studied language as involving more than logical discourse and grammatical structure because he recognized that the social context of language cannot be reduced to principles of pure reason.

Burke draws a line between a Platonic and a more contemporary view of rhetoric, described as "old rhetoric" and "new rhetoric" respectively. The former is defined by persuasion by any means, while the latter is concerned with "identification." In Burke's use of the word identification he is describing the process by which the speaker associates herself/himself with certain groups, such as a target audience. His idea of "identification" is similar to ethos of classical rhetoric, but it also explains the use of logos and pathos in an effort to create a lasting impression on the auditors. It is characterized by "identifying" with a speaker's rhetoric insofar as their words represent a world that seems to be that in which we live.[14] This theory differs from ethos most significantly in Burke's conception of artistic communication that he believes is defined by eloquence, which is "simply the end of art and therefore its essence." The use of rhetoric conveys aesthetic and social competence which is why a text can rarely be reduced to purely scientific or political implications, according to Burke. Rhetoric forms our social identity by a series of events usually based on linguistics, but more generally by the use of any symbolic figures. He uses the metaphor of a drama to articulate this point, where interdependent characters speak and communicate with each other while allowing the others to do the same. Also, Burke describes identification as a function of persuasive appeal.[15]

Burke defined rhetoric as the "use of words by human agents to form attitudes or to induce actions in other human agents."[16] His definition builds on the preexisting ideas of how people understand the meaning of rhetoric. Burke describes rhetoric as using words to move people or encourage action.[citation needed] Furthermore, he described rhetoric as being almost synonymous with persuasion (A Rhetoric of Motives, 1950). Burke argued that rhetoric works to bring about change in people. This change can be evident through attitude, motives or intentions as Burke stated but it can also be physical. Calling for help is an act of rhetoric. Rhetoric is symbolic action that calls people to physical action. Ultimately, rhetoric and persuasion become interchangeable words according to Burke. Other scholars have similar definitions of rhetoric. Aristotle argued that rhetoric was a tool for persuading people (but also for gaining information). He stated that rhetoric had the power to persuade people if the speaker knew how. One way in which Aristotle formed his arguments was through syllogism. Another example of how rhetoric was used to persuade was deliberative discourse. Here, politicians and lawyers used speech to pass or reject policies. Sally Gearhart states that rhetoric uses persuasion to induce change. Although she argues that persuasion is violent and harmful, she uses it as a tool herself to bring about change.

Philosophy

[edit]The political and social power of symbols was central to Burke's scholarship throughout his career. He felt that through understanding "what is involved when we say what people are doing and why they are doing it", we could gain insight into the cognitive basis for our perception of the world. For Burke, the way in which we decide to narrate gives importance to specific qualities over others. He believed that this could tell us a great deal about how we see the world.

Dramatism

[edit]Burke called the social and political rhetorical analysis "dramatism" and believed that such an approach to language analysis and language usage could help us understand the basis of conflict, the virtues and dangers of cooperation, and the opportunities of identification and consubstantiality.

Burke defined the rhetorical function of language as "a symbolic means of inducing cooperation in beings that by nature respond to symbols." His definition of humanity states that "man" is "the symbol using, making, and mis-using animal, inventor of the negative, separated from his natural condition by instruments of his own making, goaded by the spirit of hierarchy, and rotten with perfection."[17][18] For Burke, some of the most significant problems in human behavior resulted from instances of symbols using human beings rather than human beings using symbols.

Burke proposed that when we attribute motives to others, we tend to rely on ratios between five elements: act, scene, agent, agency, and purpose. This has become known as the dramatistic pentad. The pentad is grounded in his dramatistic method, which considers human communication as a form of action. Dramatism "invites one to consider the matter of motives in a perspective that, being developed from the analysis of drama, treats language and thought primarily as modes of action" (Grammar of Motives, xxii). Burke pursued literary criticism not as a formalistic enterprise but rather as an enterprise with significant sociological impact; he saw literature as "equipment for living," offering folk wisdom and common sense to people and thus guiding the way they lived their lives.

Rebirth cycle

[edit]Through the use of dramatism, one can ultimately utilize Burke's Rebirth Cycle. This cycle encompasses three distinct phases, which include: Guilt/Pollution, Purification, and Redemption. Burke introduced the phases and their functionality through the use of a poem. The poem follows, "Here are the steps In the Iron Law of History That welds Order and Sacrifice Order leads to Guilt (For who can keep commandments!) Guilt needs Redemption (for who would not be cleaned!) Redemption needs Redeemer (which is to say, a Victim!) Order Through Guilt To Victimage (hence: Cult of the Kill)..." (p. 4-5) [19] Burke's poem provides a basis of for the interactions of the three phases. Order's introduction into the life of human enables the creation of guilt. In order to alleviate the results produced by the creation of Guilt, redemption is necessitated. Through the abstraction of redemption, Burke leads to the completion of the cycle.

Pollution initially constitutes actions taken by an individual that result in the creation of Guilt. The creation of Guilt occurs upon the rejection of a hierarchy. Challenges to relationships, changes in power, and appropriateness of behaviors to change are each contributing factors toward the formation of Guilt.[20] It is appropriate to draw parallels between the creation of Guilt, and the concept of original sin. Original sin constitutes "an offense that cannot be avoided or a condition in which all people share".[21] Guilt represents the initial action that strips a situation of its perceived purity. The establishment of Guilt necessarily leads to the need to undergo purification to cleanse the individual affected by its recognition. Purification is thus accomplished through two forms of "ritual purification." Mortification and victimage represent the available avenues of purification.

Stratification within society created by hierarchies allows for marginalization within societies. Marginalization thus is a leading factor in the creation of Guilt, and leads to the need for mortification. Burke stated, "In an emphatic way, mortification is the exercising of oneself in 'virtue'; it is a systematic way of saying no to Disorder, or obediently saying yes to Order".[22] Mortification allows an individual's self-sacrifice which consequently enables them to rid themselves of impurities. Purification will only be reached if it is equal to an individual's degree of guilt. If mortification cannot be reached, individuals will ultimately be forced to project, "his conflict upon a scapegoat, by 'passing the buck,' by seeking a sacrificial vessel upon which he can vent, as from without, a turmoil that is actually within".[23] Sacrificial vessels allow for the extermination of an individual's Guilt while enabling them to remain virtuous. Victimage is the second form of ritual purification. Burke highlights society's need to rectify division within its ranks. He contended that "People so dislike the idea of division, their dislike can easily be turned against the man or group who would so much as name it, let alone proposing to act upon it".[24] Victimage allows for the creation of a scapegoat that serves as a depository of impurities in order to protect against entities that are alien to a particular society. The scapegoat takes on the sins of the impure, thus allowing redemption for the Guilty party. Through the course of these actions the scape goat is harnessed with the sins of the Guilty.

Redemption is reached through one of two options. Tragic redemption revolves around the idea that guilt combines with the principles of perfection and substitution in order that victimage can be utilized. This can be viewed as the "guilty is removed from the rhetorical community through either scapegoating or mortification".[25] Comic enlightenment is the second form of redemption. This option allows the sins of the guilty to be adopted by Society as a whole, ultimately making Society guilty by association.

Terministic screen

[edit]Another key concept for Burke is the Terministic screen—a set of symbols that becomes a kind of screen or grid of intelligibility through which the world makes sense to us. Here Burke offers rhetorical theorists and critics a way of understanding the relationship between language and ideology. Language, Burke thought, doesn't simply "reflect" reality; it also helps select reality as well as deflect reality. In Language as Symbolic Action (1966), he writes, "Even if any given terminology is a reflection of reality, by its very nature as a terminology it must be a selection of reality; and to this extent must function also as a deflection of reality.[26] Burke describes terministic screens as reflections of reality—we see these symbols as things that direct our attention to the topic at hand. For example, photos of the same object with different filters each direct the viewer's attention differently, much like how different subjects in academia grab the attention differently. Burke states, "We must use terministic screens, since we can't say anything without the use of terms; whatever terms we use, they necessarily constitute a corresponding kind of screen; and any such screen necessarily directs the attention to one field rather than another." Burke drew not only from the works of Shakespeare and Sophocles, but from films and radio that were important to pop culture, because they were teeming with "symbolic and rhetorical ingredients." We as a people can be cued to accept the screen put in front of us, and mass culture such as TV and websites can be to blame for this. Media today has altered terministic screens, or as Richard Toye wrote in his book Rhetoric: A Very Short Introduction, the "linguistic filters which cause us to see situations in particular fashions."[27][28]

Identification

[edit]Burke viewed identification as a critical element of persuasion.[29] According to Burke, as we listen to someone speak, we gauge how similar that person is to us. If our opinions match, then we identify (rhetorically) with the speaker.[14] Based on how much we identify with the speaker, we may be moved to accept the conclusions that the speaker comes to in an argument, as well as all (or most) of its implications. In A Rhetoric of Motives, Burke not only explores self-identification within a rhetorical context, but also analyzes exterior identification, such as identifying with objects and concepts that are not the self.[23] There are several other facets to identification that Burke discusses within his books, such as consubstantiality, property, autonomy, and cunning.

Burke's exploration of identification within rhetoric heavily influenced modern rhetorical theory. He revolutionized rhetoric in the West with his exploration of identification, arguing that rhetoric is not only about "rational argument plus emotion",[14] but also that it involves people connecting to language and one another at the same time. Burke’s theory of identification was complicated by his critical interest in music, prompting a shift toward distinguishing between form and information in sonic identification.[30]

Principal works

[edit]In "Definition of Man", the first essay of his collection Language as Symbolic Action (1966), Burke defined humankind as a "symbol using animal" (p. 3). This definition of man, he argued, means that "reality" has actually "been built up for us through nothing but our symbol systems" (p. 5). Without our encyclopedias, atlases, and other assorted reference guides, we would know little about the world that lies beyond our immediate sensory experience. What we call "reality," Burke stated, is actually a "clutter of symbols about the past combined with whatever things we know mainly through maps, magazines, newspapers, and the like about the present ... a construct of our symbol systems" (p. 5). College students wandering from class to class, from English literature to sociology to biology to calculus, encounter a new reality each time they enter a classroom; the courses listed in a university's catalogue "are in effect but so many different terminologies" (p. 5). It stands to reason then that people who consider themselves to be Christian, and who internalize that religion's symbol system, inhabit a reality that is different from the one of practicing Buddhists, or Jews, or Muslims. The same would hold true for people who believe in the tenets of free market capitalism or socialism, Freudian psychoanalysis or Jungian depth psychology, as well as mysticism or materialism. Each belief system has its own vocabulary to describe how the world works and what things mean, thus presenting its adherents with a specific reality.

Burke's poetry (which has drawn little critical attention and seldom been anthologized) appears in three collections: Book of Moments (1955), Collected Poems 1915–1967 (1968), and the posthumously published Late Poems: 1968-1993 Attitudinizings Verse-wise, While Fending for One's Selph, and in a Style Somewhat Artificially Colloquial (2005). His fiction is collected in Here & Elsewhere: The Collected Fiction of Kenneth Burke (2005).

His other principal works are

- Counter-Statement (1931)

- "Towards a Better Life" (1932), Googlebooks preview, pp. 25–233 not shown.

- Permanence and Change (1935)

- Attitudes Toward History (1937)

- The Rhetoric of Hitler's "Battle" (1939)

- Philosophy of Literary Form (1941)

- A Grammar of Motives (1945)

- A Rhetoric of Motives (1950)

- Linguistic Approaches to Problems of Education (1955)

- The Rhetoric of Religion (1961)

- Language As Symbolic Action (1966)

- Dramatism and Development (1972): a description of the contents of the two part lecture devoted to biological, psychological and sociocultural phenomena

- Here and Elsewhere (2005)

- Essays Toward a Symbolic of Motives (2006)

- Kenneth Burke on Shakespeare (2007)

- Full list of his works from KB: The Journal of the Kenneth Burke Society

He also wrote the song "One Light in a Dark Valley," later recorded by his grandson Harry Chapin.[3]

Burke's most notable correspondence is collected here:

- Jay, Paul, editor, The Selected Correspondence of Kenneth Burke and Malcolm Cowley, 1915-1981, New York: Viking, 1988, ISBN 0-670-81336-2

- East, James H., editor, The Humane Particulars: The Collected Letters of William Carlos Williams and Kenneth Burke, Columbia: U of South Carolina P, 2004.

- Rueckert, William H., editor, Letters from Kenneth Burke to William H. Rueckert, 1959–1987, Anderson, SC: Parlor Press, 2003. ISBN 0-9724772-0-9

Honors

[edit]Burke was awarded the National Medal for Literature at the American Book Awards in 1981. According to The New York Times, April 20, 1981, "The $15,000 award, endowed in memory of the late Harold Guinzberg, founder of the Viking Press, honors a living American writer 'for a distinguished and continuing contribution to American letters.'"

References

[edit]- ^ Richard Toye, Rhetoric: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- ^ "Kenneth Burke." Encyclopædia Britannica. [1] Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013.

- ^ "Kenneth Burke." Encyclopædia Britannica. [2] Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013.

- ^ Cowley, Malcolm (2014). The Long Voyage. Harvard University Press. p. 599. ISBN 9780674728226.

- ^ "Pennsylvania Center for the Book".

- ^ Wolin, Ross (2001). The Rhetorical Imagination of Kenneth Burke. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9781570034046. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ "Burke, Kenneth Duva." Edited by Bekah Shaia Dickstein, 2004. http://pabook.libraries.psu.edu/palitmap/bios/Burke__Kenneth.html Archived 2015-01-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Selzer, Jack. Kenneth Burke in Greenwich Village: Conversing with the Moderns, 1915–1931. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996.

- ^ Twentieth Century Authors: A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Literature, edited by Stanley J. Kunitz and Howard Haycraft, New York, The H. W. Wilson Company, 1942.

- ^ "Letters from Kenneth Burke to William H. Rueckert, 1959-1987", edited by William H. Rueckert, West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press, 2003.

- ^ "KENNETH BURKE, 96 PHILOSOPHER, WRITER ON LANGUAGE", Boston Globe, November 22, 1993. Accessed July 16, 2008. "Kenneth Burke, a philosopher who was influential in American literary circles, has died. He was 96. Mr. Burke died Friday of heart failure at his home in Andover, N.J."

- ^ "List of Correspondents in Kenneth Burke Papers" Archived 2012-07-16 at the Wayback Machine, Kenneth Burke Papers, Special Collections Library, Pennsylvania State University.

- ^ Mitchell, J. N. (1978). Social Exchange, Dramaturgy and Ethnomethodology: Toward a Paradigmatic Synthesis. New York: Elsevier.

- ^ a b c Keith, William M.; Lundberg, Christian Oscar (2008). The essential guide to rhetoric. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's. ISBN 978-0-312-47239-9.

- ^ Hanson, Gregory. "Kenneth Burke's Rhetorical Theory within the Construction of the Enthnography of Speaking."

- ^ Burke, Kenneth. A Rhetoric of Motives (1950), p. 41.

- ^ Burke, Kenneth. "Definition of Man." The Hudson Review 16 4 (1963/1964): 491-514

- ^ Coe, Richard M. "Defining Rhetoric—and Us: A Meditation on Burke's Definition." Composition Theory for the Postmodern Classroom. Eds. Olson, Gary A. and Sidney I. Dobrin. Albany: SUNY Press, 1994. 332-44.

- ^ Burke, Kenneth. The Rhetoric of Religion. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1961. Print.

- ^ Rybacki, Karyn & Rybacki, Donald. Communication Criticism: Approaches and Genres. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company, 1991. Print.

- ^ Foss, Sonja K., Foss, Karen A., and Trapp, Robert. Contemporary Perspectives on Rhetoric. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, Inc., 2014. Print.

- ^ Burke, Kenneth. The Rhetoric of Religion. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1961. Print.

- ^ a b Burke, Kennth. A Rhetoric of Motives. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969. Print.

- ^ Burke, Kenneth. "The Rhetoric of Hitler's "Battle." Readings in Rhetorical Criticism. Ed. Carl R. Burgchardt. State College: STRATA Publishing, Inc. 2010. 238-253.

- ^ Borchers, Timothy. Rhetorical Theory: An Introduction. Long Grove: Waveland Press, 2006.

- ^ Bizzell; Herzberg. Patricia Bizzell; Bruce Herzberg (eds.). The Rhetorical Tradition (2 ed.). pp. 1340–47.

- ^ Killian, Justin; Larson, Sean; Emanuelle Wessels. "Language as Symbolic Action". University of Minnesota. Retrieved 2014-02-19.

- ^ Toye, Richard (2013). Rhetoric: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. pp. 71–73. ISBN 978-0-19-965136-8.

- ^ Warnock, Tilly (2024). Kenneth Burke’s Rhetoric of Identification: Lessons in Reading, Writing, and Living. Anderson, South Carolina, United States: Parlor Press. pp. 1–286. ISBN 978-1643174488.

- ^ Overall, J. (2017). "Kenneth Burke and the Problem of Sonic Identification". Rhetoric Review. 36 (3): 232–243.

External links

[edit]- Author and Book Info.com offering a list of works and their description

- Kenneth Burke Papers at the Pennsylvania State University

- KB Journal, KB Journal's mission is to explore what it means to be "Burkean"

- The Kenneth Burke Society

- A short introduction to Burkean rhetoric Archived 2009-12-16 at the Wayback Machine, with all relative concepts defined

- Burke's lecture A Theory of Terms, at Drew Theological Seminary, Complete text and audio

- Works by Kenneth Burke at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- 1897 births

- 1993 deaths

- Action theorists

- American literary critics

- Bennington College faculty

- Institute for Advanced Study visiting scholars

- People from Andover, New Jersey

- People from Weehawken, New Jersey

- American rhetoricians

- Rhetoric theorists

- Shakespearean scholars

- Writers from Pittsburgh

- Communication scholars

- American philosophers of art

- American agnostics

- Former Roman Catholics

- Columbia University alumni

- Columbia College (New York) alumni

- 20th-century American philosophers

- Translators of Thomas Mann

- Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- Chapin musical family