Six-Day War

| Six-Day War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arab–Israeli conflict | |||||||||

A map of military movements during the conflict. Israel proper is shown in royal blue and territories occupied by Israel are shown in various shades of green | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

Minor involvement: | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Israel: 264,000 total[6] 250[7]–300 combat aircraft[8] 800 tanks[9] |

Egypt: 160,000 total[10] 100,000 deployed[10] 420 aircraft[11][12] 900–950 tanks[10] Syria: 75,000 troops[13] Jordan: 55,000 total[14] 45,000 deployed[15] 270 tanks[15] Iraq: 100 tanks[15] Lebanon: 2 combat aircraft[2] Total: 465,000 total[16] 800 aircraft[16] 2,504 tanks[9] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

Israel: 776–983 killed[17][18] 4,517 wounded 15 captured[17] 400 tanks destroyed[19] 46 aircraft destroyed |

Egypt: Hundreds of tanks destroyed 452+ aircraft destroyed[citation needed] | ||||||||

|

15 UN peacekeepers killed (14 Indian, 1 Brazilian)[29] 20 Israeli civilians killed and 1,000+ Israeli civilians injured in Jerusalem[30] 34 US Navy, Marine, and NSA personnel killed[31][32] 17 Soviet Marines killed (allegedly)[33] 413,000 Palestinians displaced[34] | |||||||||

The Six-Day War,[a] also known as the June War, 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states, primarily Egypt, Syria, and Jordan from 5 to 10 June 1967.

Military hostilities broke out amid poor relations between Israel and its Arab neighbors, which had been observing the 1949 Armistice Agreements signed at the end of the First Arab–Israeli War. In 1956, regional tensions over the Straits of Tiran (giving access to Eilat, a port on the southeast tip of Israel) escalated in what became known as the Suez Crisis, when Israel invaded Egypt over the Egyptian closure of maritime passageways to Israeli shipping, ultimately resulting in the re-opening of the Straits of Tiran to Israel as well as the deployment of the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) along the Egypt–Israel border.[35] In the months prior to the outbreak of the Six-Day War in June 1967, tensions again became dangerously heightened: Israel reiterated its post-1956 position that another Egyptian closure of the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping would be a definite casus belli. In May 1967, Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser announced that the Straits of Tiran would again be closed to Israeli vessels. He subsequently mobilized the Egyptian military into defensive lines along the border with Israel[36] and ordered the immediate withdrawal of all UNEF personnel.[37][29]

On 5 June 1967, as the UNEF was in the process of leaving the zone, Israel launched a series of preemptive airstrikes against Egyptian airfields and other facilities.[29] Egyptian forces were caught by surprise, and nearly all of Egypt's military aerial assets were destroyed, giving Israel air supremacy. Simultaneously, the Israeli military launched a ground offensive into Egypt's Sinai Peninsula as well as the Egyptian-occupied Gaza Strip. After some initial resistance, Nasser ordered an evacuation of the Sinai Peninsula; by the sixth day of the conflict, Israel had occupied the entire Sinai Peninsula.[38] Jordan, which had entered into a defense pact with Egypt just a week before the war began, did not take on an all-out offensive role against Israel, but launched attacks against Israeli forces to slow Israel's advance.[39] On the fifth day, Syria joined the war by shelling Israeli positions in the north.[40]

Egypt and Jordan agreed to a ceasefire on 8 June, and Syria on 9 June, and it was signed with Israel on 11 June. The Six-Day War resulted in more than 15,000 Arab fatalities, while Israel suffered fewer than 1,000. Alongside the combatant casualties were the deaths of 20 Israeli civilians killed in Arab forces air strikes on Jerusalem, 15 UN peacekeepers killed by Israeli strikes in the Sinai at the outset of the war, and 34 US personnel killed in the USS Liberty incident in which Israeli air forces struck a United States Navy technical research ship.

At the time of the cessation of hostilities, Israel had occupied the Golan Heights from Syria, the West Bank including East Jerusalem from Jordan, and the Sinai Peninsula and the Gaza Strip from Egypt. The displacement of civilian populations as a result of the Six-Day War would have long-term consequences, as around 280,000 to 325,000 Palestinians and 100,000 Syrians fled or were expelled from the West Bank[41] and the Golan Heights, respectively.[42] Nasser resigned in shame after Israel's victory, but was later reinstated following a series of protests across Egypt. In the aftermath of the conflict, Egypt closed the Suez Canal until 1975.[43]

Background

After the 1956 Suez Crisis, Egypt agreed to the stationing of a United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) in the Sinai to ensure all parties would comply with the 1949 Armistice Agreements.[45][46][47] In the following years there were numerous minor border clashes between Israel and its Arab neighbors, particularly Syria. In early November 1966, Syria signed a mutual defense agreement with Egypt.[48] Soon after this, in response to Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) guerilla activity,[49][50] including a mine attack that left three dead,[51] the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) attacked the village of as-Samu in the Jordanian-ruled West Bank.[52] Jordanian units that engaged the Israelis were quickly beaten back.[53] King Hussein of Jordan criticized Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser for failing to come to Jordan's aid, and "hiding behind UNEF skirts".[54][55][56][57]

In May 1967, Nasser received false reports from the Soviet Union that Israel was massing on the Syrian border.[58] Nasser began massing his troops in two defensive lines[36] in the Sinai Peninsula on Israel's border (16 May), expelled the UNEF force from Gaza and Sinai (19 May) and took over UNEF positions at Sharm el-Sheikh, overlooking the Straits of Tiran.[59][60] Israel repeated declarations it had made in 1957 that any closure of the Straits would be considered an act of war, or justification for war,[61][62] but Nasser closed the Straits to Israeli shipping on 22–23 May.[63][64][65] After the war, U.S. President Lyndon Johnson commented:[66]

If a single act of folly was more responsible for this explosion than any other, it was the arbitrary and dangerous announced decision that the Straits of Tiran would be closed. The right of innocent, maritime passage must be preserved for all nations.

On 30 May, Jordan and Egypt signed a defense pact. The following day, at Jordan's invitation, the Iraqi army began deploying troops and armored units in Jordan.[67] They were later reinforced by an Egyptian contingent. On 1 June, Israel formed a National Unity Government by widening its cabinet, and on 4 June the decision was made to go to war. The next morning, Israel launched Operation Focus, a large-scale, surprise air strike that launched the Six-Day War.

Military preparation

Before the war, Israeli pilots and ground crews had trained extensively in rapid refitting of aircraft returning from sorties, enabling a single aircraft to sortie up to four times a day, as opposed to the norm in Arab air forces of one or two sorties per day. This enabled the Israeli Air Force (IAF) to send several attack waves against Egyptian airfields on the first day of the war, overwhelming the Egyptian Air Force and allowed it to knock out other Arab air forces on the same day. This has contributed to the Arab belief that the IAF was helped by foreign air forces (see Controversies relating to the Six-Day War). Pilots were extensively schooled about their targets, were forced to memorize every single detail, and rehearsed the operation multiple times on dummy runways in total secrecy.

The Egyptians had constructed fortified defenses in the Sinai. These designs were based on the assumption that an attack would come along the few roads leading through the desert, rather than through the difficult desert terrain. The Israelis chose not to risk attacking the Egyptian defenses head-on, and instead surprised them from an unexpected direction.

James Reston, writing in The New York Times on 23 May 1967, noted, "In; discipline, training, morale, equipment and general competence his [Nasser's] army and the other Arab forces, without the direct assistance of the Soviet Union, are no match for the Israelis. ... Even with 50,000 troops and the best of his generals and air force in Yemen, he has not been able to work his way in that small and primitive country, and even his effort to help the Congo rebels was a flop."[68]

On the eve of the war, Israel believed it could win a war in 3–4 days. The United States estimated Israel would need 7–10 days to win, with British estimates supporting the U.S. view.[69][70]

Armies and weapons

Armies

The Israeli army had a total strength, including reservists, of 264,000, though this number could not be sustained during a long conflict, as the reservists were vital to civilian life.[6]

Against Jordan's forces on the West Bank, Israel deployed about 40,000 troops and 200 tanks (eight brigades).[71] Israeli Central Command forces consisted of five brigades. The first two were permanently stationed near Jerusalem and were the Jerusalem Brigade and the mechanized Harel Brigade. Mordechai Gur's 55th Paratroopers Brigade was summoned from the Sinai front. The 10th Armored Brigade was stationed north of the West Bank. The Israeli Northern Command comprised a division of three brigades led by Major General Elad Peled which was stationed in the Jezreel Valley to the north of the West Bank.

On the eve of the war, Egypt massed approximately 100,000 of its 160,000 troops in the Sinai, including all seven of its divisions (four infantry, two armored and one mechanized), four independent infantry brigades and four independent armored brigades. Over a third of these soldiers were veterans of Egypt's continuing intervention into the North Yemen Civil War and another third were reservists. These forces had 950 tanks, 1,100 APCs, and more than 1,000 artillery pieces.[10]

Syria's army had a total strength of 75,000 and was deployed along the border with Israel.[13] Professor David W. Lesch wrote that "One would be hard-pressed to find a military less prepared for war with a clearly superior foe" since Syria's army had been decimated in the months and years prior through coups and attempted coups that had resulted in a series of purges, fracturings and uprisings within the armed forces.[72]

The Jordanian Armed Forces included 11 brigades, totaling 55,000 troops.[14] Nine brigades (45,000 troops, 270 tanks, 200 artillery pieces) were deployed in the West Bank, including the elite armored 40th, and two in the Jordan Valley. They possessed sizable numbers of M113 APCs and were equipped with some 300 modern Western tanks, 250 of which were U.S. M48 Pattons. They also had 12 battalions of artillery, six batteries of 81 mm and 120 mm mortars,[15] a paratrooper battalion trained in the new U.S.-built school and a new battalion of mechanized infantry. The Jordanian Army was a long-term-service, professional army, relatively well-equipped and well-trained. Israeli post-war briefings said that the Jordanian staff acted professionally, but was always left "half a step" behind by the Israeli moves. The small Royal Jordanian Air Force consisted of only 24 British-made Hawker Hunter fighters, six transport aircraft and two helicopters. According to the Israelis, the Hawker Hunter was essentially on par with the French-built Dassault Mirage III – the IAF's best plane.[73]

One hundred Iraqi tanks and an infantry division were readied near the Jordanian border. Two squadrons of Iraqi fighter-aircraft, Hawker Hunters and MiG 21s, were rebased adjacent to the Jordanian border.[15]

In the weeks leading up to the Six-Day War, Saudi Arabia mobilized forces for deployment to the Jordanian front. A Saudi infantry battalion entered Jordan on 6 June 1967, followed by another on the 8th. Both were based in Jordan's southernmost city, Ma'an. By 17 June, the Saudi contingent in Jordan had grown to include a single infantry brigade, a tank company, two artillery batteries, a heavy mortar company, and a maintenance and support unit. By the end of July 1967, a second tank company and a third artillery battery had been added. These forces remained in Jordan until the end of 1977, when they were recalled for re-equipment and retraining in the Karak region near the Dead Sea.[74][75][76]

The Arab air forces were reinforced by aircraft from Libya, Algeria, Morocco, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia to make up for the massive losses suffered on the first day of the war. They were also aided by volunteer pilots from the Pakistan Air Force acting in an independent capacity. PAF pilots like Saiful Azam shot down several Israeli planes.[77][78]

Weapons

With the exception of Jordan, the Arabs relied principally on Soviet weaponry. Jordan's army was equipped with American weaponry, and its air force was composed of British aircraft.

Egypt had by far the largest and the most modern of all the Arab air forces, consisting of about 420 combat aircraft,[11][12] all of them Soviet-built and with a large number of top-of-the-line MiG-21s. Of particular concern to the Israelis were the 30 Tu-16 "Badger" medium bombers, capable of inflicting heavy damage on Israeli military and civilian centers.[79]

Israeli weapons were mainly of Western origin. Its air force was composed principally of French aircraft, while its armored units were mostly of British and American design and manufacture. Some light infantry weapons, including the ubiquitous Uzi, were of Israeli origin.

Fighting fronts

Initial attack

The first and most critical move of the conflict was a surprise Israeli attack on the Egyptian Air Force. Initially, both Egypt and Israel announced that they had been attacked by the other country.[82]

On 5 June at 7:45 Israeli time, with civil defense sirens sounding all over Israel, the IAF launched Operation Focus (Moked). All but 12 of its nearly 200 operational jets[83] launched a mass attack against Egypt's airfields.[84] The Egyptian defensive infrastructure was extremely poor, and no airfields were yet equipped with hardened aircraft shelters capable of protecting Egypt's warplanes. Most of the Israeli warplanes headed out over the Mediterranean Sea, flying low to avoid radar detection, before turning toward Egypt. Others flew over the Red Sea.[85]

Meanwhile, the Egyptians hindered their own defense by effectively shutting down their entire air defense system: they were worried that rebel Egyptian forces would shoot down the plane carrying Field Marshal Abdel Hakim Amer and Lt-Gen. Sidqi Mahmoud, who were en route from al Maza to Bir Tamada in the Sinai to meet the commanders of the troops stationed there. It did not make a great deal of difference as the Israeli pilots came in below Egyptian radar cover and well below the lowest point at which its SA-2 surface-to-air missile batteries could bring down an aircraft.[86]

Although the powerful Jordanian radar facility at Ajloun detected waves of aircraft approaching Egypt and reported the code word for "war" up the Egyptian command chain, Egyptian command and communications problems prevented the warning from reaching the targeted airfields.[85] The Israelis employed a mixed-attack strategy: bombing and strafing runs against planes parked on the ground, and bombing to disable runways with special tarmac-shredding penetration bombs developed jointly with France, leaving surviving aircraft unable to take off.[7]

The runway at the Arish airfield was spared, as the Israelis expected to turn it into a military airport for their transports after the war. Surviving aircraft were taken out by later attack waves. The operation was more successful than expected, catching the Egyptians by surprise and destroying virtually all of the Egyptian Air Force on the ground, with few Israeli losses. Only four unarmed Egyptian training flights were in the air when the strike began.[7] A total of 338 Egyptian aircraft were destroyed and 100 pilots were killed,[87] although the number of aircraft lost by the Egyptians is disputed.[88]

Among the Egyptian planes lost were all 30 Tu-16 bombers, 27 out of 40 Il-28 bombers, 12 Su-7 fighter-bombers, over 90 MiG-21s, 20 MiG-19s, 25 MiG-17 fighters, and around 32 transport planes and helicopters. In addition, Egyptian radars and SAM missiles were also attacked and destroyed. The Israelis lost 19 planes, including two destroyed in air-to-air combat and 13 downed by anti-aircraft artillery.[89] One Israeli plane, which was damaged and unable to break radio silence, was shot down by Israeli Hawk missiles after it strayed over the Negev Nuclear Research Center.[90] Another was destroyed by an exploding Egyptian bomber.[91]

The attack guaranteed Israeli air supremacy for the rest of the war. Attacks on other Arab air forces by Israel took place later in the day as hostilities broke out on other fronts.

The large numbers of Arab aircraft claimed destroyed by Israel on that day were at first regarded as "greatly exaggerated" by the Western press, but the fact that the Egyptian Air Force, along with other Arab air forces attacked by Israel, made practically no appearance for the remaining days of the conflict proved that the numbers were most likely authentic. Throughout the war, Israeli aircraft continued strafing Arab airfield runways to prevent their return to usability. Meanwhile, Egyptian state-run radio had reported an Egyptian victory, falsely claiming that 70 Israeli planes had been downed on the first day of fighting.[92]

Gaza Strip and Sinai Peninsula

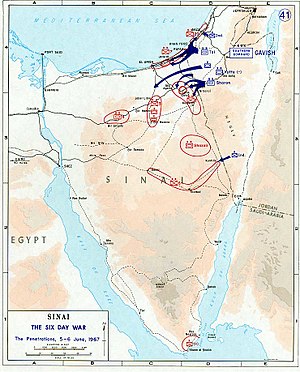

The Egyptian forces consisted of seven divisions: four armored, two infantry, and one mechanized infantry. Overall, Egypt had around 100,000 troops and 900–950 tanks in the Sinai, backed by 1,100 APCs and 1,000 artillery pieces.[10] This arrangement was thought to be based on the Soviet doctrine, where mobile armor units at strategic depth provide a dynamic defense while infantry units engage in defensive battles.

Israeli forces concentrated on the border with Egypt included six armored brigades, one infantry brigade, one mechanized infantry brigade, three paratrooper brigades, giving a total of around 70,000 men and 700 tanks, who were organized in three armored divisions. They had massed on the border the night before the war, camouflaging themselves and observing radio silence before being ordered to advance.[citation needed]

The Israeli plan was to surprise the Egyptian forces in both timing (the attack exactly coinciding with the IAF strike on Egyptian airfields), and in location (attacking via northern and central Sinai routes, as opposed to the Egyptian expectations of a repeat of the 1956 war, when the IDF attacked via the central and southern routes) and method (using a combined-force flanking approach, rather than direct tank assaults).[citation needed]

Northern (El Arish) Israeli division

On 5 June, at 7:50 am, the northernmost Israeli division, consisting of three brigades and commanded by Major General Israel Tal, one of Israel's most prominent armor commanders, crossed the border at two points, opposite Nahal Oz and south of Khan Yunis. They advanced swiftly, holding fire to prolong the element of surprise. Tal's forces assaulted the "Rafah Gap", an 11-kilometre (7 mi) stretch containing the shortest of three main routes through the Sinai towards El Qantara and the Suez Canal. The Egyptians had four divisions in the area, backed by minefields, pillboxes, underground bunkers, hidden gun emplacements and trenches. The terrain on either side of the route was impassable. The Israeli plan was to hit the Egyptians at selected key points with concentrated armor.[90]

Tal's advance was led by the 7th Armored Brigade under Colonel Shmuel Gonen. The Israeli plan called for the 7th Brigade to outflank Khan Yunis from the north and the 60th Armored Brigade under Colonel Menachem Aviram would advance from the south. The two brigades would link up and surround Khan Yunis, while the paratroopers would take Rafah. Gonen entrusted the breakthrough to a single battalion of his brigade.[93]

Initially, the advance was met with light resistance, as Egyptian intelligence had concluded that it was a diversion for the main attack. As Gonen's lead battalion advanced, it suddenly came under intense fire and took heavy losses. A second battalion was brought up, but was also pinned down. Meanwhile, the 60th Brigade became bogged down in the sand, while the paratroopers had trouble navigating through the dunes. The Israelis continued to press their attack, and despite heavy losses, cleared the Egyptian positions and reached the Khan Yunis railway junction in a little over four hours.[93]

Gonen's brigade then advanced nine miles to Rafah in twin columns. Rafah itself was circumvented, and the Israelis attacked Sheikh Zuweid, 13 kilometres (8 mi) to the southwest, which was defended by two brigades. Though inferior in numbers and equipment, the Egyptians were deeply entrenched and camouflaged. The Israelis were pinned down by fierce Egyptian resistance and called in air and artillery support to enable their lead elements to advance. Many Egyptians abandoned their positions after their commander and several of his staff were killed.[93]

The Israelis broke through with tank-led assaults, but Aviram's forces misjudged the Egyptians' flank and were pinned between strongholds before they were extracted after several hours. By nightfall, the Israelis had finished mopping up resistance. Israeli forces had taken significant losses, with Colonel Gonen later telling reporters that "we left many of our dead soldiers in Rafah and many burnt-out tanks." The Egyptians suffered some 2,000 casualties and lost 40 tanks.[93]

Advance on Arish

On 5 June, with the road open, Israeli forces continued advancing towards Arish. Already by late afternoon, elements of the 79th Armored Battalion had charged through the 11-kilometre (7 mi)-long Jiradi defile, a narrow pass defended by well-emplaced troops of the Egyptian 112th Infantry Brigade. In fierce fighting, which saw the pass change hands several times, the Israelis charged through the position. The Egyptians suffered heavy casualties and tank losses, while Israeli losses stood at 66 dead, 93 wounded and 28 tanks. Emerging at the western end, Israeli forces advanced to the outskirts of Arish.[94] As it reached the outskirts of Arish, Tal's division also consolidated its hold on Rafah and Khan Yunis.

The following day, 6 June, the Israeli forces on the outskirts of Arish were reinforced by the 7th Brigade, which fought its way through the Jiradi pass. After receiving supplies via an airdrop, the Israelis entered the city and captured the airport at 7:50 am. The Israelis entered the city at 8:00 am. Company commander Yossi Peled recounted that "Al-Arish was totally quiet, desolate. Suddenly, the city turned into a madhouse. Shots came at us from every alley, every corner, every window and house." An IDF record stated that "clearing the city was hard fighting. The Egyptians fired from the rooftops, from balconies and windows. They dropped grenades into our half-tracks and blocked the streets with trucks. Our men threw the grenades back and crushed the trucks with their tanks."[95][96] Gonen sent additional units to Arish, and the city was eventually taken.

Brigadier-General Avraham Yoffe's assignment was to penetrate Sinai south of Tal's forces and north of Sharon's. Yoffe's attack allowed Tal to complete the capture of the Jiradi defile, Khan Yunis. All of them were taken after fierce fighting. Gonen subsequently dispatched a force of tanks, infantry and engineers under Colonel Yisrael Granit to continue down the Mediterranean coast towards the Suez Canal, while a second force led by Gonen himself turned south and captured Bir Lahfan and Jabal Libni.[citation needed]

Mid-front (Abu-Ageila) Israeli division

Further south, on 6 June, the Israeli 38th Armored Division under Major-General Ariel Sharon assaulted Um-Katef, a heavily fortified area defended by the Egyptian 2nd Infantry Division under Major-General Sa'adi Naguib (though Naguib was actually absent[97]) of Soviet World War II armor, which included 90 T-34-85 tanks, 22 SU-100 tank destroyers, and about 16,000 men. The Israelis had about 14,000 men and 150 post-World War II tanks including the AMX-13, Centurions, and M50 Super Shermans (modified M-4 Sherman tanks).[citation needed]

Two armored brigades in the meantime, under Avraham Yoffe, slipped across the border through sandy wastes that Egypt had left undefended because they were considered impassable. Simultaneously, Sharon's tanks from the west were to engage Egyptian forces on Um-Katef ridge and block any reinforcements. Israeli infantry would clear the three trenches, while heliborne paratroopers would land behind Egyptian lines and silence their artillery. An armored thrust would be made at al-Qusmaya to unnerve and isolate its garrison.[citation needed]

As Sharon's division advanced into the Sinai, Egyptian forces staged successful delaying actions at Tarat Umm, Umm Tarfa, and Hill 181. An Israeli jet was downed by anti-aircraft fire, and Sharon's forces came under heavy shelling as they advanced from the north and west. The Israeli advance, which had to cope with extensive minefields, took a large number of casualties. A column of Israeli tanks managed to penetrate the northern flank of Abu Ageila, and by dusk, all units were in position. The Israelis then brought up ninety 105 mm and 155 mm artillery cannon for a preparatory barrage, while civilian buses brought reserve infantrymen under Colonel Yekutiel Adam and helicopters arrived to ferry the paratroopers. These movements were unobserved by the Egyptians, who were preoccupied with Israeli probes against their perimeter.[98]

As night fell, the Israeli assault troops lit flashlights, each battalion a different colour, to prevent friendly fire incidents. At 10:00 pm, Israeli artillery began a barrage on Um-Katef, firing some 6,000 shells in less than twenty minutes, the most concentrated artillery barrage in Israel's history.[99][100] Israeli tanks assaulted the northernmost Egyptian defenses and were largely successful, though an entire armored brigade was stalled by mines, and had only one mine-clearance tank. Israeli infantrymen assaulted the triple line of trenches in the east. To the west, paratroopers commanded by Colonel Danny Matt landed behind Egyptian lines, though half the helicopters got lost and never found the battlefield, while others were unable to land due to mortar fire.[101][102]

Those that successfully landed on target destroyed Egyptian artillery and ammunition dumps and separated gun crews from their batteries, sowing enough confusion to significantly reduce Egyptian artillery fire. Egyptian reinforcements from Jabal Libni advanced towards Um-Katef to counterattack but failed to reach their objective, being subjected to heavy air attacks and encountering Israeli lodgements on the roads. Egyptian commanders then called in artillery attacks on their own positions. The Israelis accomplished and sometimes exceeded their overall plan, and had largely succeeded by the following day. The Egyptians suffered about 2,000 casualties, while the Israelis lost 42 dead and 140 wounded.[101][102][103]

Yoffe's attack allowed Sharon to complete the capture of the Um-Katef, after fierce fighting. The main thrust at Um-Katef was stalled due to mines and craters. After IDF engineers had cleared a path by 4:00 pm, Israeli and Egyptian tanks engaged in fierce combat, often at ranges as close as ten yards. The battle ended in an Israeli victory, with 40 Egyptian and 19 Israeli tanks destroyed. Meanwhile, Israeli infantry finished clearing out the Egyptian trenches, with Israeli casualties standing at 14 dead and 41 wounded and Egyptian casualties at 300 dead and 100 taken prisoner.[104]

Other Israeli forces

Further south, on 5 June, the 8th Armored Brigade under Colonel Albert Mandler, initially positioned as a ruse to draw off Egyptian forces from the real invasion routes, attacked the fortified bunkers at Kuntilla, a strategically valuable position whose capture would enable Mandler to block reinforcements from reaching Um-Katef and to join Sharon's upcoming attack on Nakhl. The defending Egyptian battalion outnumbered and outgunned, fiercely resisted the attack, hitting several Israeli tanks. Most of the defenders were killed, and only three Egyptian tanks, one of them damaged, survived. By nightfall, Mandler's forces had taken Kuntilla.[95]

With the exceptions of Rafah and Khan Yunis, Israeli forces had initially avoided entering the Gaza Strip. Israeli Defense Minister Moshe Dayan had expressly forbidden entry into the area. After Palestinian positions in Gaza opened fire on the Negev settlements of Nirim and Kissufim, IDF Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin overrode Dayan's instructions and ordered the 11th Mechanized Brigade under Colonel Yehuda Reshef to enter the Strip. The force was immediately met with heavy artillery fire and fierce resistance from Palestinian forces and remnants of the Egyptian forces from Rafah.[citation needed]

By sunset, the Israelis had taken the strategically vital Ali Muntar ridge, overlooking Gaza City, but were beaten back from the city itself. Some 70 Israelis were killed, along with Israeli journalist Ben Oyserman and American journalist Paul Schutzer. Twelve members of UNEF were also killed. On the war's second day, 6 June, the Israelis were bolstered by the 35th Paratroopers Brigade under Colonel Rafael Eitan and took Gaza City along with the entire Strip. The fighting was fierce and accounted for nearly half of all Israeli casualties on the southern front. Gaza rapidly fell to the Israelis.[citation needed]

Meanwhile, on 6 June, two Israeli reserve brigades under Yoffe, each equipped with 100 tanks, penetrated the Sinai south of Tal's division and north of Sharon's, capturing the road junctions of Abu Ageila, Bir Lahfan, and Arish, taking all of them before midnight. Two Egyptian armored brigades counterattacked, and a fierce battle took place until the following morning. The Egyptians were beaten back by fierce resistance coupled with airstrikes, sustaining heavy tank losses. They fled west towards Jabal Libni.[105]

The Egyptian Army

During the ground fighting, remnants of the Egyptian Air Force attacked Israeli ground forces but took losses from the Israeli Air Force and from Israeli anti-aircraft units. Throughout the last four days, Egyptian aircraft flew 150 sorties against Israeli units in the Sinai.[citation needed]

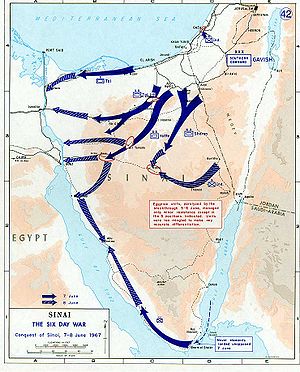

Many of the Egyptian units remained intact and could have tried to prevent the Israelis from reaching the Suez Canal, or engaged in combat in the attempt to reach the canal, but when the Egyptian Field Marshal Abdel Hakim Amer heard about the fall of Abu-Ageila, he panicked and ordered all units in the Sinai to retreat. This order effectively meant the defeat of Egypt.[citation needed]

Meanwhile, President Nasser, having learned of the results of the Israeli air strikes, decided together with Field Marshal Amer to order a general retreat from the Sinai within 24 hours. No detailed instructions were given concerning the manner and sequence of withdrawal.[106]

Next fighting days

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2017) |

As Egyptian columns retreated, Israeli aircraft and artillery attacked them. Israeli jets used napalm bombs during their sorties. The attacks destroyed hundreds of vehicles and caused heavy casualties. At Jabal Libni, retreating Egyptian soldiers were fired upon by their own artillery. At Bir Gafgafa, the Egyptians fiercely resisted advancing Israeli forces, knocking out three tanks and eight half-tracks, and killing 20 soldiers. Due to the Egyptians' retreat, the Israeli High Command decided not to pursue the Egyptian units but rather to bypass and destroy them in the mountainous passes of West Sinai.[citation needed]

Therefore, in the following two days (6 and 7 June), all three Israeli divisions (Sharon and Tal were reinforced by an armored brigade each) rushed westwards and reached the passes. Sharon's division first went southward then westward, via An-Nakhl, to Mitla Pass with air support. It was joined there by parts of Yoffe's division, while its other units blocked the Gidi Pass. These passes became killing grounds for the Egyptians, who ran right into waiting Israeli positions and suffered heavy losses in both soldiers and vehicles. According to Egyptian diplomat Mahmoud Riad, 10,000 men were killed in one day alone, and many others died from thirst. Tal's units stopped at various points to the length of the Suez Canal.[citation needed]

Israel's blocking action was partially successful. Only the Gidi pass was captured before the Egyptians approached it, but at other places, Egyptian units managed to pass through and cross the canal to safety. Due to the haste of the Egyptian retreat, soldiers often abandoned weapons, military equipment, and hundreds of vehicles. Many Egyptian soldiers were cut off from their units had to walk about 200 kilometres (120 mi) on foot before reaching the Suez Canal with limited supplies of food and water and were exposed to intense heat. Thousands died as a result. Many Egyptian soldiers chose instead to surrender to the Israelis, who eventually exceeded their capabilities to provide for prisoners. As a result, they began directing soldiers towards the Suez Canal and only imprisoned high-ranking officers, who were expected to be exchanged for captured Israeli pilots.[citation needed]

According to some accounts, during the Egyptian retreat from the Sinai, a unit of Soviet Marines based on a Soviet warship in Port Said at the time came ashore and attempted to cross the Suez Canal eastward. The Soviet force was reportedly decimated by an Israeli air attack and lost 17 dead and 34 wounded. Among the wounded was the commander, Lt. Col. Victor Shevchenko.[33]

During the offensive, the Israeli Navy landed six combat divers from the Shayetet 13 naval commando unit to infiltrate Alexandria harbor. The divers sank an Egyptian minesweeper before being taken prisoner. Shayetet 13 commandos also infiltrated Port Said harbor, but found no ships there. A planned commando raid against the Syrian Navy never materialized. Both Egyptian and Israeli warships made movements at sea to intimidate the other side throughout the war but did not engage each other. Israeli warships and aircraft hunted for Egyptian submarines throughout the war.[citation needed]

On 7 June, Israel began its attack on Sharm el-Sheikh. The Israeli Navy started the operation with a probe of Egyptian naval defenses. An aerial reconnaissance flight found that the area was less defended than originally thought. At about 4:30 am, three Israeli missile boats opened fire on Egyptian shore batteries, while paratroopers and commandos boarded helicopters and Nord Noratlas transport planes for an assault on Al-Tur, as Chief of Staff Rabin was convinced it was too risky to land them directly in Sharm el-Sheikh.[107] The city had been largely abandoned the day before, and reports from air and naval forces finally convinced Rabin to divert the aircraft to Sharm el-Sheikh. There, the Israelis engaged in a pitched battle with the Egyptians and took the city, killing 20 Egyptian soldiers and taking eight more prisoners. At 12:15 pm, Defense Minister Dayan announced that the Straits of Tiran constituted an international waterway open to all ships without restriction.[107]

On 8 June, Israel completed the capture of the Sinai by sending infantry units to Ras Sudar on the western coast of the peninsula.

Several tactical elements made the swift Israeli advance possible:

- The surprise attack that quickly gave the Israeli Air Force complete air superiority over the Egyptian Air Force.

- The determined implementation of an innovative battle plan.

- The lack of coordination among Egyptian troops.

These factors would prove to be decisive elements on Israel's other fronts as well.[citation needed]

West Bank

Egyptian control of Jordanian forces

King Hussein had given control of his army to Egypt on 1 June, on which date Egyptian General Riad arrived in Amman to take control of the Jordanian military.[b]

Egyptian Field Marshal Amer used the confusion of the first hours of the conflict to send a cable to Amman that he was victorious; he claimed as evidence a radar sighting of a squadron of Israeli aircraft returning from bombing raids in Egypt, which he said was an Egyptian aircraft en route to attack Israel.[109] In this cable, sent shortly before 9:00 am, Riad was ordered to attack.[c]

Initial attack

One of the Jordanian brigades stationed in the West Bank was sent to the Hebron area in order to link with the Egyptians.

The IDF's strategic plan was to remain on the defensive along the Jordanian front, to enable focus in the expected campaign against Egypt.

Intermittent machine-gun exchanges began taking place in Jerusalem at 9:30 am, and the fighting gradually escalated as the Jordanians introduced mortar and recoilless rifle fire. Under the orders from General Narkis, the Israelis responded only with small-arms fire, firing in a flat trajectory to avoid hitting civilians, holy sites or the Old City. At 10:00 am on 5 June, the Jordanian Army began shelling Israel. Two batteries of 155 mm Long Tom cannons opened fire on the suburbs of Tel Aviv and Ramat David Airbase. The commanders of these batteries were instructed to lay a two-hour barrage against military and civilian settlements in central Israel. Some shells hit the outskirts of Tel Aviv.[111]

By 10:30 am, Eshkol had sent a message via Odd Bull to King Hussein promising not to initiate any action against Jordan if it stayed out of the war.[112] King Hussein replied that it was too late, and "the die was cast".[113] At 11:15 am, Jordanian howitzers began a 6,000-shell barrage at Israeli Jerusalem. The Jordanians initially targeted kibbutz Ramat Rachel in the south and Mount Scopus in the north, then ranged into the city center and outlying neighborhoods. Military installations, the Prime Minister's Residence, and the Knesset compound were also targeted. Jordanian forces shelled the Beit HaNassi and the Biblical Zoo, killing fifteen civilians.[114][115] Israeli civilian casualties totalled 20 dead and over 1,000 wounded. Some 900 buildings were damaged, including Hadassah Ein Kerem Hospital, which had its Chagall-made windows destroyed.[116]

At 11:50 am, sixteen Jordanian Hawker Hunters attacked Netanya, Kfar Sirkin and Kfar Saba, killing one civilian, wounding seven and destroying a transport plane. Three Iraqi Hawker Hunters strafed civilian settlements in the Jezreel Valley, and an Iraqi Tupolev Tu-16 attacked Afula, and was shot down near the Megiddo airfield. The attack caused minimal material damage, hitting only a senior citizens' home and several chicken coops, but sixteen Israeli soldiers were killed, most of them when the Tupolev crashed.[116]

Israeli cabinet meets

When the Israeli cabinet convened to decide on a plan of action, Yigal Allon and Menahem Begin argued that this was an opportunity to take the Old City of Jerusalem, but Eshkol decided to defer any decision until Moshe Dayan and Yitzhak Rabin could be consulted.[117] Uzi Narkiss made proposals for military action, including the capture of Latrun, but the cabinet turned him down. Dayan rejected multiple requests from Narkiss for permission to mount an infantry assault towards Mount Scopus but sanctioned some limited retaliatory actions.[118]

Initial response

Shortly before 12:30 pm, the Israeli Air Force attacked Jordan's two airbases. The Hawker Hunters were refueling at the time of the attack. The Israeli aircraft attacked in two waves, the first of which cratered the runways and knocked out the control towers, and the second wave destroyed all 21 of Jordan's Hawker Hunter fighters, along with six transport aircraft and two helicopters. One Israeli jet was shot down by ground fire.[118]

Israeli aircraft also attacked H-3, an Iraqi Air Force base in western Iraq. During the attack, 12 MiG-21s, 2 MiG-17s, 5 Hunter F6s, and 3 Il-28 bombers were destroyed or shot down. A Pakistani pilot stationed at the base, Saiful Azam, who was posted with the Royal Jordanian Air Force as an advisor, shot down an Israeli fighter and a bomber during the raid. The Jordanian radar facility at Ajloun was destroyed in an Israeli airstrike. Israeli Fouga Magister jets attacked the Jordanian 40th Brigade with rockets as it moved south from the Damia Bridge. Dozens of tanks were knocked out, and a convoy of 26 trucks carrying ammunition was destroyed. In Jerusalem, Israel responded to Jordanian shelling with a missile strike that devastated Jordanian positions. The Israelis used the L missile, a surface-to-surface missile developed jointly with France in secret.[118]

Jordanian battalion at Government House

A Jordanian battalion advanced up Government House ridge and dug in at the perimeter of Government House, the headquarters of the United Nations observers,[119][120][121] and opened fire on Ramat Rachel, the Allenby Barracks and the Jewish section of Abu Tor with mortars and recoilless rifles. UN observers fiercely protested the incursion into the neutral zone, and several manhandled a Jordanian machine gun out of Government House after the crew had set it up in a second-floor window. After the Jordanians occupied Jabel Mukaber, an advance patrol was sent out and approached Ramat Rachel, where they came under fire from four civilians, including the wife of the director, who were armed with old Czech-made weapons.[122][123]

The immediate Israeli response was an offensive to retake Government House and its ridge. The Jerusalem Brigade's Reserve Battalion 161, under Lieutenant-Colonel Asher Dreizin, was given the task. Dreizin had two infantry companies and eight tanks under his command, several of which broke down or became stuck in the mud at Ramat Rachel, leaving three for the assault. The Jordanians mounted fierce resistance, knocking out two tanks.[124]

The Israelis broke through the compound's western gate and began clearing the building with grenades, before General Odd Bull, commander of the UN observers, compelled the Israelis to hold their fire, telling them that the Jordanians had already fled. The Israelis proceeded to take the Antenna Hill, directly behind Government House, and clear out a series of bunkers to the west and south. The fighting often conducted hand-to-hand, continued for nearly four hours before the surviving Jordanians fell back to trenches held by the Hittin Brigade, which were steadily overwhelmed. By 6:30 am, the Jordanians had retreated to Bethlehem, having suffered about 100 casualties. All but ten of Dreizin's soldiers were casualties, and Dreizin himself was wounded three times.[124]

Israeli invasion

During the late afternoon of 5 June, the Israelis launched an offensive to encircle Jerusalem, which lasted into the following day. During the night, they were supported by intense tank, artillery and mortar fire to soften up Jordanian positions. Searchlights placed atop the Labor Federation building, then the tallest in Israeli Jerusalem, exposed and blinded the Jordanians. The Jerusalem Brigade moved south of Jerusalem, while the mechanized Harel Brigade and 55th Paratroopers Brigade under Mordechai Gur encircled it from the north.[125]

A combined force of tanks and paratroopers crossed no-man's land near the Mandelbaum Gate. Gur's 66th paratroop battalion approached the fortified Police Academy. The Israelis used Bangalore torpedoes to blast their way through barbed wire leading up to the position while exposed and under heavy fire. With the aid of two tanks borrowed from the Jerusalem Brigade, they captured the Police Academy. After receiving reinforcements, they moved up to attack Ammunition Hill.[125][126]

The Jordanian defenders, who were heavily dug-in, fiercely resisted the attack. All of the Israeli officers except for two company commanders were killed, and the fighting was mostly led by individual soldiers. The fighting was conducted at close quarters in trenches and bunkers and was often hand-to-hand. The Israelis captured the position after four hours of heavy fighting. During the battle, 36 Israeli and 71 Jordanian soldiers were killed.[125][126] Even after the fighting on Ammunition Hill had ended, Israeli soldiers were forced to remain in the trenches due to Jordanian sniper fire from Givat HaMivtar until the Harel Brigade overran that outpost in the afternoon.[127]

The 66th battalion subsequently drove east, and linked up with the Israeli enclave on Mount Scopus and its Hebrew University campus. Gur's other battalions, the 71st and 28th captured the other Jordanian positions around the American Colony, despite being short on men and equipment and having come under a Jordanian mortar bombardment while waiting for the signal to advance.[125][126]

At the same time, the IDF's 4th Brigade attacked the fortress at Latrun, which the Jordanians had abandoned due to heavy Israeli tank fire. The mechanized Harel Brigade attacked Har Adar, but seven tanks were knocked out by mines, forcing the infantry to mount an assault without armored cover. The Israeli soldiers advanced under heavy fire, jumping between rocks to avoid mines and the fighting was conducted at close quarters with knives and bayonets.[citation needed]

The Jordanians fell back after a battle that left two Israeli and eight Jordanian soldiers dead, and Israeli forces advanced through Beit Horon towards Ramallah, taking four fortified villages along the way. By the evening, the brigade arrived in Ramallah. Meanwhile, the 163rd Infantry Battalion secured Abu Tor following a fierce battle, severing the Old City from Bethlehem and Hebron.[citation needed]

Meanwhile, 600 Egyptian commandos stationed in the West Bank moved to attack Israeli airfields. Led by Jordanian intelligence scouts, they crossed the border and began infiltrating through Israeli settlements towards Ramla and Hatzor. They were soon detected and sought shelter in nearby fields, which the Israelis set on fire. Some 450 commandos were killed, and the remainder escaped to Jordan.[128]

From the American Colony, the paratroopers moved towards the Old City. Their plan was to approach it via the lightly defended Salah al-Din Street but made a wrong turn onto the heavily defended Nablus Road and ran into fierce resistance. Their tanks fired at point-blank range down the street, while the paratroopers mounted repeated charges. Despite repelling repeated Israeli charges, the Jordanians gradually gave way to Israeli firepower and momentum. The Israelis suffered some 30 casualties – half the original force – while the Jordanians lost 45 dead and 142 wounded.[129]

Meanwhile, the Israeli 71st Battalion breached barbed wire and minefields and emerged near Wadi Joz, near the base of Mount Scopus, from where the Old City could be cut off from Jericho and East Jerusalem from Ramallah. Israeli artillery targeted the one remaining route from Jerusalem to the West Bank, and shellfire deterred the Jordanians from counterattacking from their positions at Augusta-Victoria. An Israeli detachment then captured the Rockefeller Museum after a brief skirmish.[129]

Afterwards, the Israelis broke through to the Jerusalem-Ramallah road. At Tel al-Ful, the Harel Brigade fought a running battle with up to thirty Jordanian tanks. The Jordanians stalled the advance and destroyed some half-tracks, but the Israelis launched air attacks and exploited the vulnerability of the external fuel tanks mounted on the Jordanian tanks. The Jordanians lost half their tanks, and retreated towards Jericho. Joining up with the 4th Brigade, the Israelis then descended through Shuafat and the site of what is now French Hill, through Jordanian defenses at Mivtar, emerging at Ammunition Hill.[130]

With Jordanian defenses in Jerusalem crumbling, elements of the Jordanian 60th Brigade and an infantry battalion were sent from Jericho to reinforce Jerusalem. Its original orders were to repel the Israelis from the Latrun corridor, but due to the worsening situation in Jerusalem, the brigade was ordered to proceed to Jerusalem's Arab suburbs and attack Mount Scopus. Parallel to the brigade were infantrymen from the Imam Ali Brigade, who were approaching Issawiya. The brigades were spotted by Israeli aircraft and decimated by rocket and cannon fire. Other Jordanian attempts to reinforce Jerusalem were beaten back, either by armored ambushes or airstrikes.[citation needed]

Fearing damage to holy sites and the prospect of having to fight in built-up areas, Dayan ordered his troops not to enter the Old City.[117] He also feared that Israel would be subjected to a fierce international backlash and the outrage of Christians worldwide if it forced its way into the Old City. Privately, he told David Ben-Gurion that he was also concerned over the prospect of Israel capturing Jerusalem's holy sites, only to be forced to give them up under the threat of international sanctions.[citation needed]

The West Bank

Israel was to gain almost total control of the West Bank by the evening of 7 June,[131] and began its military occupation of the West Bank on that day, issuing a military order, the "Proclamation Regarding Law and Administration (The West Bank Area) (No. 2)—1967", which established the military government in the West Bank and granted the commander of the area full legislative, executive, and judicial power.[132][5] Jordan had realised that it had no hope of defense as early as the morning of 6 June, just a day after the conflict had begun.[133] At Nasser's request, Egypt's Abdul Munim Riad sent a situation update at midday on 6 June:[131]

The situation on the West Bank is rapidly deteriorating. A concentrated attack has been launched on all axes, together with heavy fire, day and night. Jordanian, Syrian and Iraqi air forces in position H3 have been virtually destroyed. Upon consultation with King Hussein I have been asked to convey to you the following choices:

- 1. A political decision to cease fighting to be imposed by a third party (the USA, the Soviet Union or the Security Council).

- 2. To vacate the West Bank tonight.

- 3. To go on fighting for one more day, resulting in the isolation and destruction of the entire Jordanian Army.

King Hussein has asked me to refer this matter to you for an immediate reply.

An Egyptian order for Jordanian forces to withdraw across the Jordan River was issued at 10 am on 6 June; that afternoon King Hussein learned of the impending United Nations Security Council Resolution 233 and decided instead to hold out in the hope that a ceasefire would be implemented soon. It was already too late, as the counter-order caused confusion and in many cases, it was not possible to regain positions that had been left.[134]

On 7 June, Dayan ordered his troops not to enter the Old City but, upon hearing that the UN was about to declare a ceasefire, he changed his mind, and without cabinet clearance, decided to capture it.[117] Two paratroop battalions attacked Augusta-Victoria Hill, high ground overlooking the Old City from the east. One battalion attacked from Mount Scopus, and another attacked from the valley between it and the Old City. Another paratroop battalion, personally led by Gur, broke into the Old City and was joined by the other two battalions after their missions were complete. The paratroopers met little resistance. The fighting was conducted solely by the paratroopers; the Israelis did not use armor during the battle out of fear of severe damage to the Old City.

In the north, a battalion from Peled's division checked Jordanian defenses in the Jordan Valley. A brigade from Peled's division captured the western part of the West Bank. One brigade attacked Jordanian artillery positions around Jenin, which were shelling Ramat David Airbase. The Jordanian 12th Armored Battalion, which outnumbered the Israelis, held off repeated attempts to capture Jenin. Israeli air attacks took their toll, and the Jordanian M48 Pattons, with their external fuel tanks, proved vulnerable at short distances, even to the Israeli-modified Shermans. Twelve Jordanian tanks were destroyed, and only six remained operational.[128]

Just after dusk, Israeli reinforcements arrived. The Jordanians continued to fiercely resist, and the Israelis were unable to advance without artillery and air support. One Israeli jet attacked the Jordanian commander's tank, wounding him and killing his radio operator and intelligence officer. The surviving Jordanian forces then withdrew to Jenin, where they were reinforced by the 25th Infantry Brigade. The Jordanians were effectively surrounded in Jenin.[128]

Jordanian infantry and their three remaining tanks managed to hold off the Israelis until 4:00 am, when three battalions arrived to reinforce them in the afternoon. The Jordanian tanks charged and knocked out multiple Israeli vehicles, and the tide began to shift. After sunrise, Israeli jets and artillery conducted a two-hour bombardment against the Jordanians. The Jordanians lost 10 dead and 250 wounded, and had only seven tanks left, including two without gas, and sixteen APCs. The Israelis then fought their way into Jenin and captured the city after fierce fighting.[135]

After the Old City fell, the Jerusalem Brigade reinforced the paratroopers, and continued to the south, capturing Judea and Gush Etzion. Hebron was taken without any resistance.[136] Fearful that Israeli soldiers would exact retribution for the 1929 massacre of the city's Jewish community, Hebron's residents flew white sheets from their windows and rooftops.[137] The Harel Brigade proceeded eastward, descending to the Jordan River.

On 7 June, Israeli forces seized Bethlehem, taking the city after a brief battle that left some 40 Jordanian soldiers dead, with the remainder fleeing. On the same day, one of Peled's brigades seized Nablus; then it joined one of Central Command's armored brigades to fight the Jordanian forces; as the Jordanians held the advantage of superior equipment and were equal in numbers to the Israelis.

Again, the air superiority of the IAF proved paramount as it immobilized the Jordanians, leading to their defeat. One of Peled's brigades joined with its Central Command counterparts coming from Ramallah, and the remaining two blocked the Jordan river crossings together with the Central Command's 10th. Engineering Corps sappers blew up the Abdullah and Hussein bridges with captured Jordanian mortar shells, while elements of the Harel Brigade crossed the river and occupied positions along the east bank to cover them, but quickly pulled back due to American pressure. The Jordanians, anticipating an Israeli offensive deep into Jordan, assembled the remnants of their army and Iraqi units in Jordan to protect the western approaches to Amman and the southern slopes of the Golan Heights.

As Israel continued its offensive on 7 June, taking no account of the UN ceasefire resolution, the Egyptian-Jordanian command ordered a full Jordanian withdrawal for the second time, in order to avoid an annihilation of the Jordanian army.[138] This was complete by nightfall on 7 June.[138]

After the Old City was captured, Dayan told his troops to "dig in" to hold it. When an armored brigade commander entered the West Bank on his own initiative, and stated that he could see Jericho, Dayan ordered him back. It was only after intelligence reports indicated that Hussein had withdrawn his forces across the Jordan River that Dayan ordered his troops to capture the West Bank.[121] According to Narkis:

First, the Israeli government had no intention of capturing the West Bank. On the contrary, it was opposed to it. Second, there was not any provocation on the part of the IDF. Third, the rein was only loosened when a real threat to Jerusalem's security emerged. This is truly how things happened on June 5, although it is difficult to believe. The end result was something that no one had planned.[139]

Golan Heights

In May–June 1967, in preparation for conflict, the Israeli government planned to confine the confrontation to the Egyptian front, whilst taking into account the possibility of some fighting on the Syrian front.[113]

Syrian front 5–8 June

Syria largely stayed out of the conflict for the first four days.[140][141]

False Egyptian reports of a crushing victory against the Israeli army[92] and forecasts that Egyptian forces would soon be attacking Tel Aviv influenced Syria's decision to enter the war – in a sporadic manner – during this period.[140] Syrian artillery began shelling northern Israel, and twelve Syrian jets attacked Israeli settlements in the Galilee. Israeli fighter jets intercepted the Syrian aircraft, shooting down three and driving off the rest.[142] In addition, two Lebanese Hawker Hunter jets, two of the twelve Lebanon had, crossed into Israeli airspace and began strafing Israeli positions in the Galilee. They were intercepted by Israeli fighter jets, and one was shot down.[2]

On the evening of 5 June, the Israeli Air Force attacked Syrian airfields. The Syrian Air Force lost some 32 MiG 21s, 23 MiG-15 and MiG-17 fighters, and two Ilyushin Il-28 bombers, two-thirds of its fighting strength. The Syrian aircraft that survived the attack retreated to distant bases and played no further role in the war. Following the attack, Syria realized that the news it had received from Egypt of the near-total destruction of the Israeli military could not have been true.[142]

On 6 June, a minor Syrian force tried to capture the water plants at Tel Dan (the subject of a fierce escalation two years earlier), Dan, and She'ar Yashuv. These attacks were repulsed with the loss of twenty soldiers and seven tanks. An Israeli officer was also killed. But a broader Syrian offensive quickly failed. Syrian reserve units were broken up by Israeli air attacks, and several tanks were reported to have sunk in the Jordan River.[142]

Other problems included tanks being too wide for bridges, lack of radio communications between tanks and infantry, and units ignoring orders to advance. A post-war Syrian army report concluded:

Our forces did not go on the offensive either because they did not arrive or were not wholly prepared or because they could not find shelter from the enemy's aircraft. The reserves could not withstand the air attacks; they dispersed after their morale plummeted.[143]

The Syrians bombarded Israeli civilian settlements in the Galilee Panhandle with two battalions of M-46 130mm guns, four companies of heavy mortars, and dug-in Panzer IV tanks. The Syrian bombardment killed two civilians and hit 205 houses as well as farming installations. An inaccurate report from a Syrian officer said that as a result of the bombardment that "the enemy appears to have suffered heavy losses and is retreating".[40]

Israelis debate whether the Golan Heights should be attacked

On 7 and 8 June, the Israeli leadership debated about whether to attack the Golan Heights as well. Syria had supported pre-war raids that had helped raise tensions and had routinely shelled Israel from the Heights, so some Israeli leaders wanted to see Syria punished.[144] Military opinion was that the attack would be extremely costly since it would entail an uphill battle against a strongly fortified enemy. The western side of the Golan Heights consists of a rock escarpment that rises 500 meters (1,700 ft) from the Sea of Galilee and the Jordan River, and then flattens to a gently sloping plateau. Dayan opposed the operation bitterly at first, believing such an undertaking would result in losses of 30,000 and might trigger Soviet intervention. Prime Minister Eshkol, on the other hand, was more open to the possibility, as was the head of the Northern Command, David Elazar, whose unbridled enthusiasm for and confidence in the operation may have eroded Dayan's reluctance.[citation needed]

Eventually, the situation on the Southern and Central fronts cleared up, intelligence estimated that the likelihood of Soviet intervention had been reduced, reconnaissance showed some Syrian defenses in the Golan region collapsing, and an intercepted cable revealed that Nasser was urging the President of Syria to immediately accept a ceasefire. At 3 AM on 9 June, Syria announced its acceptance of the ceasefire. Despite this announcement, Dayan became more enthusiastic about the idea and four hours later at 7 AM, "gave the order to go into action against Syria"[d][144] without consultation or government authorization.[146]

The Syrian army consisted of about 75,000 men grouped in nine brigades, supported by an adequate amount of artillery and armor. Israeli forces used in combat consisted of two brigades (the 8th Armored Brigade and the Golani Brigade) in the northern part of the front at Givat HaEm, and another two (infantry and one of Peled's brigades summoned from Jenin) in the center. The Golan Heights' unique terrain (mountainous slopes crossed by parallel streams every several kilometers running east to west), and the general lack of roads in the area channeled both forces along east–west axes of movement and restricted the ability of units to support those on either flank. Thus the Syrians could move north–south on the plateau itself, and the Israelis could move north–south at the base of the Golan escarpment. An advantage Israel possessed was the intelligence collected by Mossad operative Eli Cohen (who was captured and executed in Syria in 1965) regarding the Syrian battle positions. Syria had built extensive defensive fortifications in depths up to 15 kilometers.[147]

As opposed to all the other campaigns, IAF was only partially effective in the Golan because the fixed fortifications were so effective. The Syrian forces proved unable to put up effective defense largely because the officers were poor leaders and treated their soldiers badly; often officers would retreat from danger, leaving their men confused and ineffective. The Israelis also had the upper hand during close combat that took place in the numerous Syrian bunkers along the Golan Heights, as they were armed with the Uzi, a submachine gun designed for close combat, while Syrian soldiers were armed with the heavier AK-47 assault rifle, designed for combat in more open areas.[citation needed]

Israeli attack: first day (9 June)

On the morning of 9 June, Israeli jets began carrying out dozens of sorties against Syrian positions from Mount Hermon to Tawfiq, using rockets salvaged from captured Egyptian stocks. The airstrikes knocked out artillery batteries and storehouses and forced transport columns off the roads. The Syrians suffered heavy casualties and a drop in morale, with some senior officers and troops deserting. The attacks also provided time as Israeli forces cleared paths through Syrian minefields. The airstrikes did not seriously damage the Syrians' bunkers and trench systems, and the bulk of Syrian forces on the Golan remained in their positions.[148]

About two hours after the airstrikes began, the 8th Armored Brigade, led by Colonel Albert Mandler, advanced into the Golan Heights from Givat HaEm. Its advance was spearheaded by Engineering Corps sappers and eight bulldozers, which cleared away barbed wire and mines. As they advanced, the force came under fire, and five bulldozers were immediately hit. The Israeli tanks, with their manoeuvrability sharply reduced by the terrain, advanced slowly under fire toward the fortified village of Sir al-Dib, with their ultimate objective being the fortress at Qala. Israeli casualties steadily mounted.[149]

Part of the attacking force lost its way and emerged opposite Za'ura, a redoubt manned by Syrian reservists. With the situation critical, Colonel Mandler ordered simultaneous assaults on Za'ura and Qala. Heavy and confused fighting followed, with Israeli and Syrian tanks struggling around obstacles and firing at extremely short ranges. Mandler recalled that "the Syrians fought well and bloodied us. We beat them only by crushing them under our treads and by blasting them with our cannons at very short range, from 100 to 500 meters." The first three Israeli tanks to enter Qala were stopped by a Syrian bazooka team, and a relief column of seven Syrian tanks arrived to repel the attackers.[149]

The Israelis took heavy fire from the houses, but could not turn back, as other forces were advancing behind them, and they were on a narrow path with mines on either side. The Israelis continued pressing forward and called for air support. A pair of Israeli jets destroyed two of the Syrian tanks, and the remainder withdrew. The surviving defenders of Qala retreated after their commander was killed. Meanwhile, Za'ura fell in an Israeli assault, and the Israelis also captured the 'Ein Fit fortress.[149]

In the central sector, the Israeli 181st Battalion captured the strongholds of Dardara and Tel Hillal after fierce fighting. Desperate fighting also broke out along the operation's northern axis, where Golani Brigade attacked thirteen Syrian positions, including the formidable Tel Fakhr position. Navigational errors placed the Israelis directly under the Syrians' guns. In the fighting that followed, both sides took heavy casualties, with the Israelis losing all nineteen of their tanks and half-tracks.[150] The Israeli battalion commander then ordered his twenty-five remaining men to dismount, divide into two groups, and charge the northern and southern flanks of Tel Fakhr. The first Israelis to reach the perimeter of the southern approach laid on the barbed wire, allowing their comrades to vault over them. From there, they assaulted the fortified Syrian positions. The fighting was waged at extremely close quarters, often hand-to-hand.[150]

On the northern flank, the Israelis broke through within minutes and cleared out the trenches and bunkers. During the seven-hour battle, the Israelis lost 31 dead and 82 wounded, while the Syrians lost 62 dead and 20 captured. Among the dead was the Israeli battalion commander. The Golani Brigade's 51st Battalion took Tel 'Azzaziat, and Darbashiya also fell to Israeli forces.[150]

By the evening of 9 June, the four Israeli brigades had all broken through to the plateau, where they could be reinforced and replaced. Thousands of reinforcements began reaching the front, those tanks and half-tracks that had survived the previous day's fighting were refuelled and replenished with ammunition, and the wounded were evacuated. By dawn, the Israelis had eight brigades in the sector.[citation needed]

Syria's first line of defense had been shattered, but the defenses beyond that remained largely intact. Mount Hermon and the Banias in the north, and the entire sector between Tawfiq and Customs House Road in the south remained in Syrian hands. In a meeting early on the night of 9 June, Syrian leaders decided to reinforce those positions as quickly as possible and to maintain a steady barrage on Israeli civilian settlements.[citation needed]

Israeli attack: second day (10 June)

Throughout the night, the Israelis continued their advance, though it was slowed by fierce resistance. An anticipated Syrian counterattack never materialized. At the fortified village of Jalabina, a garrison of Syrian reservists, levelling their anti-aircraft guns, held off the Israeli 65th Paratroop Battalion for four hours before a small detachment managed to penetrate the village and knock out the heavy guns.[citation needed]

Meanwhile, the 8th Brigade's tanks moved south from Qala, advancing six miles to Wasit under heavy artillery and tank bombardment. At the Banias in the north, Syrian mortar batteries opened fire on advancing Israeli forces only after Golani Brigade sappers cleared a path through a minefield, killing sixteen Israeli soldiers and wounding four.[citation needed]

On the next day, 10 June, the central and northern groups joined in a pincer movement on the plateau, but that fell mainly on empty territory as the Syrian forces retreated. At 8:30 am, the Syrians began blowing up their own bunkers, burning documents and retreating. Several units joined by Elad Peled's troops climbed to the Golan from the south, only to find the positions mostly empty. When the 8th Brigade reached Mansura, five miles from Wasit, the Israelis met no opposition and found abandoned equipment, including tanks, in perfect working condition. In the fortified Banias village, Golani Brigade troops found only several Syrian soldiers chained to their positions.[151]

During the day, the Israeli units stopped after obtaining manoeuvre room between their positions and a line of volcanic hills to the west. In some locations, Israeli troops advanced after an agreed-upon cease-fire[152] to occupy strategically strong positions.[153] To the east, the ground terrain is an open gently sloping plain. This position later became the cease-fire line known as the "Purple Line".

Time magazine reported: "In an effort to pressure the United Nations into enforcing a ceasefire, Damascus Radio undercut its own army by broadcasting the fall of the city of Quneitra three hours before it actually capitulated. That premature report of the surrender of their headquarters destroyed the morale of the Syrian troops left in the Golan area."[154]

Conclusion

A week ago, the fateful campaign began. The existence of the State of Israel hung in the balance, the hopes of generations, and the vision that was realised in our own time... During the fighting, our forces destroyed about 450 enemy planes and hundreds of tanks. The enemy forces were decisively defeated in battles. Many fled for their lives or were captured. For the first time since the establishment of the state, the threat to our security has been removed at once from the Sinai Peninsula, the Gaza Strip, Jerusalem, the West Bank and the northern border.

– Levi Eshkol, 12 June 1967 (Address to Israeli Parliament)[155]

By 10 June, Israel had completed its final offensive in the Golan Heights, and a ceasefire was signed the day after. Israel had seized the Gaza Strip, the Sinai Peninsula, the West Bank of the Jordan River (including East Jerusalem), and the Golan Heights.[156] About one million Arabs were placed under Israel's direct control in the newly captured territories. Israel's strategic depth grew to at least 300 kilometers in the south, 60 kilometers in the east, and 20 kilometers of extremely rugged terrain in the north, a security asset that would prove useful in the Yom Kippur War six years later.

Speaking three weeks after the war ended, as he accepted an honorary degree from Hebrew University, Yitzhak Rabin gave his reasoning behind the success of Israel:

Our airmen, who struck the enemies' planes so accurately that no one in the world understands how it was done and people seek technological explanations or secret weapons; our armoured troops who beat the enemy even when their equipment was inferior to his; our soldiers in all other branches ... who overcame our enemies everywhere, despite the latter's superior numbers and fortifications—all these revealed not only coolness and courage in the battle but ... an understanding that only their personal stand against the greatest dangers would achieve victory for their country and for their families, and that if victory was not theirs the alternative was annihilation.[157]

In recognition of contributions, Rabin was given the honor of naming the war for the Israelis. From the suggestions proposed, including the "War of Daring", "War of Salvation", and "War of the Sons of Light", he "chose the least ostentatious, the Six-Day War, evoking the days of creation".[158]

Dayan's final report on the war to the Israeli general staff listed several shortcomings in Israel's actions, including misinterpretation of Nasser's intentions, overdependence on the United States, and reluctance to act when Egypt closed the Straits. He also credited several factors for Israel's success: Egypt did not appreciate the advantage of striking first and their adversaries did not accurately gauge Israel's strength and its willingness to use it.[158]

In Egypt, according to Heikal, Nasser had admitted his responsibility for the military defeat in June 1967.[159] According to historian Abd al-Azim Ramadan, Nasser's mistaken decisions to expel the international peacekeeping force from the Sinai Peninsula and close the Straits of Tiran in 1967 led to a state of war with Israel, despite Egypt's lack of military preparedness.[160]

After the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Egypt reviewed the causes of its loss of the 1967 war. Issues that were identified included "the individualistic bureaucratic leadership"; "promotions on the basis of loyalty, not expertise, and the army's fear of telling Nasser the truth"; lack of intelligence; and better Israeli weapons, command, organization, and will to fight.[158]

Casualties

Between 776[18] and 983 Israelis were killed and 4,517 were wounded. Fifteen Israeli soldiers were captured. Arab casualties were far greater. Between 9,800[20] and 15,000[21] Egyptian soldiers were listed as killed or missing in action. An additional 4,338 Egyptian soldiers were captured.[22] Jordanian losses are estimated to be 700 killed in action with another 2,500 wounded.[17][26] The Syrians were estimated to have sustained between 1,000[161] and 2,500[23][25] killed in action. Between 367[22] and 591[24] Syrians were captured.

Casualties were also suffered by UNEF, the United Nations Emergency Force that was stationed on the Egyptian side of the border. In three different episodes, Israeli forces attacked a UNEF convoy, camps in which UNEF personnel were concentrated and the UNEF headquarters in Gaza,[29] resulting in one Brazilian peacekeeper and 14 Indian officials killed by Israeli forces, with an additional seventeen peacekeepers wounded in both contingents.[29]

Controversies

Preventative war vs war of aggression

At the commencement of hostilities, both Egypt and Israel announced that they had been attacked by the other country.[82] The Israeli government later abandoned its initial position, acknowledging Israel had struck first, claiming that it was a preemptive strike in the face of a planned invasion by Egypt.[82][38] The Arab view was that it was unjustified to attack Egypt.[162][163] Many scholars consider the war a case of preventative war as a form of self-defense.[164][165] The war has been assessed by others as a war of aggression.[166]

Allegations of atrocities committed against Egyptian soldiers

It has been alleged that Nasser did not want Egypt to learn of the true extent of his defeat and so ordered the killing of Egyptian army stragglers making their way back to the Suez canal zone.[167] There have also been allegations from both Israeli and Egyptian sources that Israeli troops killed unarmed Egyptian prisoners.[168][169][170][171][172][173][174][175][176]

Allegations of military support from the US, UK and Soviet Union

There have been allegations of direct military support of Israel during the war by the US and the UK, including the supply of equipment (despite an embargo) and the participation of US forces in the conflict.[177][178][179][180][181] Many of these allegations and conspiracy theories[182] have been disputed and it has been claimed that some were given currency in the Arab world to explain the Arab defeat.[183] It has also been claimed that the Soviet Union, in support of its Arab allies, used its naval strength in the Mediterranean to act as a major restraint on the US Navy.[184][185]

America features prominently in Arab conspiracy theories purporting to explain the June 1967 defeat. Mohamed Hassanein Heikal, a confidant of Nasser, claims that President Lyndon B. Johnson was obsessed with Nasser and that Johnson conspired with Israel to bring him down.[186] The reported Israeli troop movements seemed all the more threatening because they were perceived in the context of a US conspiracy against Egypt. Salah Bassiouny of the Foreign Ministry, claims that Foreign Ministry saw the reported Israeli troop movements as credible because Israel had reached the level at which it could find strategic alliance with the United States.[187]

During the war, Cairo announced that American and British planes were participating in the Israeli attack. Nasser broke off diplomatic relations following this allegation. Nasser's image of the United States was such that he might well have believed the worst. Anwar Sadat implied that Nasser used this deliberate conspiracy in order to accuse the United States as a political cover-up for domestic consumption.[188] Lutfi Abd al-Qadir, the director of Radio Cairo during the late 1960s, who accompanied Nasser to his visits in Moscow, had his conspiracy theory that both the Soviets and the Western powers wanted to topple Nasser or to reduce his influence.[189]

USS Liberty incident

On 8 June 1967, USS Liberty, a United States Navy electronic intelligence vessel sailing 13 nautical miles (24 km) off Arish (just outside Egypt's territorial waters), was attacked by Israeli jets and torpedo boats, nearly sinking the ship, killing 34 sailors and wounding 171. Israel said the attack was a case of mistaken identity, and that the ship had been misidentified as the Egyptian vessel El Quseir. Israel apologized for the mistake and paid compensation to the victims or their families, and to the United States for damage to the ship. After an investigation, the U.S. accepted the explanation that the incident was an accident and the issue was closed by the exchange of diplomatic notes in 1987. Others, including the then United States Secretary of State Dean Rusk and Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Thomas Moorer, some survivors of the attack, and intelligence officials familiar with transcripts of intercepted signals on the day, have rejected these conclusions as unsatisfactory and maintain that the attack was made in the knowledge that the ship was American.[190][191][192]

Aftermath