Sixty-six (card game)

| "One of the best two-handers ever devised" | |

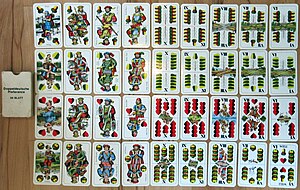

German–French cards for Sechsundsechzig | |

| Origin | German |

|---|---|

| Type | Point-trick |

| Players | 2 |

| Cards | 24 |

| Deck | French or German-suited pack |

| Rank (high→low) | A 10 K Q J 9 |

| Play | Clockwise |

| Playing time | 15 min. |

| Chance | Medium |

| Related games | |

| Mariage, Schnapsen | |

Sixty-six or 66 (German: Sechsundsechzig), sometimes known as Paderbörnern,[a] is a fast 5- or 6-card point-trick game of the marriage type for 2–4 players, played with 24 cards. It is an ace–ten game where aces are high and tens rank second. It has been described as "one of the best two-handers ever devised".[1]

Closely related games for various numbers of players are popular all over Europe and include Austria's national card game, Schnapsen, the Czech/Slovak Mariáš, Hungarian Ulti, Finnish Marjapussi and French Bezique. American pinochle also descends from this family. Together with the jack–nine family, these form the large king–queen family of games.[2]

History

[edit]

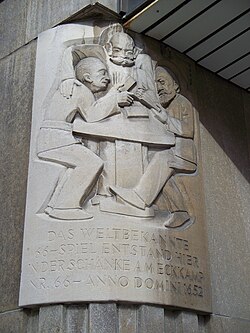

The ancestor of sixty-six is the German game of Mariage, which was first recorded in 1715 under the name Mariagen-Spiel[3] "despite claims for its invention at Paderborn, Westphalia, in 1652".[1] Although there is a commemorative plaque in Paderborn at Kamp 17 stating that the "world famous game of Sixty-Six was invented here in the pub at No. 66, Am Eckkamp in 1652",[4][b] the conclusion of a 1960 investigation was that the story was probably a 19th century invention.[5]

Sixty-six appeared in German card game compendia as a variant of Mariage around 1860, the main differences being that it was played with 24, not 32, cards, the bonuses for amour (holding the trump Ace and Ten in the hand) and whitewashing (taking all six last tricks) were dropped, and players could 'go out' on reaching 66 without playing to the end (whereupon the winner of the last trick won the game regardless). The last mentioned rule had been introduced to Mariage late in the day (for a score of 101 points).[6]

In the Leipzig dialect, the game was known as Schnorps, Schnarps, Schnarpsen or Schnorpsen. [7]

In 1901, sixty-six was reported to be one of the most popular penny ante games in the city of Pforzheim in Baden alongside Cego, Skat, Tapp and Tarrock (possibly Dreierles).[8]

Sixty-six was widely played by Polish Americans in South Bend, Indiana, in the 1950s and '60s. There were regular tournaments and money games. Bidding was usually in Polish. There was a four-hand partnership game and a three-hand, "cut-throat" game involving seven cards per hand and a widow of three cards won by the first trick. Both were played to 15 points. In the 1970s and '80s, a more aggressive bidding approach was developed in familial games known as the Kromkowski style. [9][c]

Overview

[edit]Sixty-six is a 6-card game played with a deck of 24 cards consisting of the ace, ten, king, queen, jack, and nine, worth 11, 10, 4, 3, 2 and 0 card-points, respectively (by comparison, its close cousin, the Austrian game of Schnapsen does not make use of the nines and has a hand size of 5 cards). The trump suit is determined randomly. Players each begin with a full hand and draw from the stock after each trick. The object in each deal is to be the first player to score 66 points. The cards have a total worth of 120 points, and the last trick is worth 10 points. A player who holds king and queen of the same suit scores 20 points, or 40 points in trumps, when playing the first of them.

Cards

[edit]The choice of card deck varies from region to region, but the game is usually played with French-suited cards or double German cards. For tournaments in which players of different regions compete, there are special German–French decks. Sechsundsechzig is played with a pack of 24 cards.

There are six cards per suit in Sechsundsechzig:

| Playing card suits | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| French deck | ||||

| German deck | ||||

| Name of the suits | Hearts (Herz) | Diamonds (Karo) | Spades (Pik) | Clubs (Kreuz, Treff) |

Card values

[edit]The table shows the cards ranked from highest to lowest and their card point value once taken. Many central European games use this valuation. The ranking is different from standard British or North American ranking in that the ten ranks high, i.e. it is the second highest card after the ace.

| Card values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name (Fr., Ger.) | Card points | |||

| Ace (Ass), deuce (Daus) | 11 | |||

| Ten (Zehner) | 10 | |||

| King (König) | 4 | |||

| Ober, queen (Ober, Dame) | 3 | |||

| Unter, jack (Unter, Bube) | 2 | |||

| Nine (Neuner) | 0 | |||

Rules

[edit]Deal

[edit]Dealer is determined by any method acceptable to both players. The deal then alternates between players. Each player is dealt six cards in two packets of 3, beginning with the non-dealer, and the top card of the remaining deck is turned face-up to show the trump suit. The remaining undealt cards are placed crosswise on the trump card to form the talon or stock.

Play

[edit]The non-dealer leads to the first trick. A trick is taken by the highest card of the suit led that is in the trick, unless the trick contains a card from the trump suit, in which case it is taken by the highest trump card in the trick. Until the stock is gone, there is no obligation to follow suit or to trump. The trick is taken by the winner, turned face down, and should not be looked at again. The winner scores the value of the two cards in the trick, as shown on the table above. Players must remember how many points they have taken since their scores may not be recorded, and they are not allowed to look back at previous tricks. Once the trick is played, the winner takes the top card of the talon to replenish his hand, then the loser does the same. The winner of the trick leads to the next trick.

Nine of trumps

[edit]The holder of the lowest trump card, the nine, may exchange it for the face up trump card under the talon. This can be done only by a player who has the lead and has won at least one trick. This exchange cannot be done in the middle of a trick. It must be done just after the players restock their hands, when no cards are in play.

Marriages or pairs

[edit]On his turn when he has the lead, a player may meld a queen–king 'marriage' or an Ober–Unter 'pair' of the same suit by playing one and simultaneously showing the other. Regular marriages (or pairs) are worth 20 points and trump marriages are worth 40. A marriage or pair is usually announced in some way to the other player, often by saying the number of points made ("twenty" or "forty"). The points do not count towards the player's total until he has taken at least one trick.

Talon depleted

[edit]Once the talon is gone, with the turned up trump taken by the loser of the sixth trick, the rules of play change to become more strict. Players now must follow the suit led (winning the trick when possible), they must trump if they have no cards of the suit led, and marriages can no longer be played.

Closing

[edit]Closing indicates that the closer has a good enough hand to reach the 66-point target under the stock-depleted rules above. The player must be on lead to the next trick in order to close. It is indicated by turning over the face-up trump card, before or after taking cards to make the hands back up to 6 cards. The rules change to the strict rules given above for play after the stock is depleted. The stock is now "closed" and players do not replenish their hands, and there is no 10-point bonus for taking the last trick. If the closer reaches 66 card points first, he scores game points as described below. If he fails to reach 66 card-points or his opponent reaches 66 card points first, his opponent scores 2 game points, or 3 if that opponent has no tricks.

Declaring

[edit]

A player who thinks that the points in the tricks he or she has taken together with those from any marriages add up to 66 or more, stops the game and begins counting card points. If the player who stopped the game does not have 66 card and marriage points, then the opponent wins 2 game points, or 3 if that opponent has taken no tricks. If the player does have 66 points, then he or she wins game points as follows.

- One game point if the opponent has 33 or more card points.

- Two game points if the opponent won at least one trick and has 0–32 card points.

- Three game points if the opponent won no tricks at all.

Winning

[edit]The first person to get seven game points is the winner.

Variants

[edit]Schnapsen

[edit]

The Austrian national two-handed variation of sixty-six in which all the nines are removed for a 20- rather than a 24-card deck, and the hand size is reduced from six to five cards. There are several other important changes to the rules in Schnapsen from those given above for Sixty-Six:[10]

- The trump exchange is done by a player on lead who holds the trump Jack or trump Unter rather than the trump Nine.

- If the stock is depleted, the winner of the last trick is given an outright win of the hand rather than a 10 card-point bonus.

- Marriages by the player on lead are allowed even when the stock is depleted or closed.

- The stock can be closed only after replenishing both hands to five cards.

Many minor variations on the rules of both Schnapsen and sixty-six exist.[10]

Schnapsen is considered a much tighter game than the 24-card version and is particularly popular in Austria and Hungary, where they sell specialized packs of cards called Schnapskarten specifically to play this game. It is regarded as a very strategic game, and articles and books have been written about winning strategy.[11][12]

Four-handed and North American 66

[edit]North-American sixty-six is also a partnership game which uses a 24-card pack ranking 9, 10, jack, queen, king, and ace. A deck can be made with the cards 8 and below removed from a standard playing card deck. The game is played by two, three or four (in teams of two). Team members sit across from each other.[13]

Scoring points

[edit]Each team gets a black 6 and a red 4, used for scoring. In Polish American communities of South Bend, Indiana, the game is played to 15, so a 7 and 8 are used for scoring.[9] There are 30 points per suit, for a total of 120 points in the deck. Points are distributed amongst the cards as shown in the table.

In addition, points are awarded to players who have a marriage or meld. In order to get the points for the meld and marriage, the king or queen must be led (i.e. the first card played in the trick) and the other card must be in the same player's hand. It is not necessary to take the trick, just to lead. But the team may only count the meld if during the course of the hand they win at least one trick. The player must announce the marriage (as "40" or "20") when leading, otherwise the player does not receive the award. 40 points are awarded for a meld/marriage in trump, 20 points are awarded for a non-trump meld.

Points are kept in 33-point increments. Score is kept up to 10 points. Although, in money games and among certain playing communities the game has always traditionally been played to 15 points.

Bidding

[edit]The play to the left of the dealer initiates bidding. Bidding is done based on how many points the player thinks they will make in the hand. Each player either bids greater than the previous bid or passes. Each player bids or passes only once. The player who has the highest bid leads. Trump is determined by the first card played. Each tick on the scoresheet is 33 points. Bids are not additive: if your partner bids 1 and you bid 2, the bid for that hand is 2, not 3. Since bidding is based on number of points you want to take, bids equate to the following:

- A bid of 1 is for 33 points – This can be fairly simple, since the player who gets the bid determines what trump is. If he has an Ace/Ten or Ace and two others in the same suit, a 1 bid may be safe. There are only 30 points per suit. If the player has a "marriage", he can lead that for 40 points, so he is always safe to bid 1 with a marriage.

- A bid of 2 is for 66 points – This is slightly more than half the points in the deck. Rule-of-thumb – you should bid 2 when you have a marriage, because you already have 40 (you only need 26 more). Chances are that your partner will give you those points to reach your 2 bid.

- A bid of 3 is for 99 points – This is tough, but with a trump marriage and strong trump, it is doable.

- A bid of 4 is for 132 points – There are only 120 points in the deck, so this requires a meld to make it. Generally people do not bid 4.

- A bid of 5 (also known as "moon" or "playing alone") – The partner's hand is placed face down and the partner does not play. Play is only between the 3 remaining players.

The bidding difficulty describes pre-1970s money games. Since then, innovations were made using aggressive bidding, notable in South Bend, Indiana.[9] This aggressive style of play was previously discouraged by money rules which penalized losing bids: "A dollar a point, and a dollar a set." Consequently, players were not able to work out the optimal odds and circumstances favoring a more aggressive bidding style which was allowed in family friendly games where younger players were free to push the boundaries without fear of losing money (or card room brawls.)[9]

Play

[edit]After the players bid, the player who bid highest begins play. The first card led is automatically trump.

Players must follow suit. If a player has the ability to play higher, they must play higher. If a player does not have the led suit, but does have trump, the player must play trump. This can be a useful way of removing trump from your opponent while getting rid of low-point cards, i.e., the 9s. If the player does not have the led suit or trump, his partner is free to play any of the remaining cards.

Scoring

[edit]The team that bid highest must make their bid in order to score. Failure to do so results in a reduction of points. At the end of the hand, teams count up their points and add in the points of any called marriages. If the marriage wasn't led, it isn't scored.

For the opponents, for every 33 points, score one on the scorecards. For the bidding team, if they made their bid, score one on the scorecard for every 33 points. If they were set, remove the bid from their scorecard.

In close matches, the rule is "bidders out". Meaning that if both teams pass 15 on the last hand, the team that won the bid, is the winner.[9]

It is important to note that there is no penalty in underbidding. If a player overbids, however, his partner is set to bid again. The opposing team gets points based on what they collect. If they collect 35 points, they make one on the scorecard.

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The name Paderbörnern relates to the story that the game originated in the city of Paderborn. See the History section.

- ^ See also the city's tourist information web pages.

- ^ The Kromkowski family worked out odds and circumstances favouring higher bidding strategies. This involves, in part, understanding the card distribution. From your hand cards and the bids of other players, you can assess what others hold. The process is remarkably similar to a hidden Markov model (HMM), a statistical model in which the system being modelled is assumed to be a Markov process with unknown parameters, and the challenge is to determine the hidden parameters (the other hands) from the observable parameters (your hand and the bids).

References

[edit]- ^ a b Parlett 2008, p. 261.

- ^ Parlett 1996, p. 259.

- ^ Corvinus 1715, pp. 1234–1235.

- ^ Text of the commemorative plaque at Kamp 17, Paderborn.

- ^ Pöppel (1960).

- ^ von Thalberg 1860, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Albrecht 1881, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Stolz (1901), p. 592.

- ^ a b c d e Mucha, Janusz (1996). "Everyday Life and Festivity in a Local Ethnic Community: Polish-Americans in South Bend, Indiana" East European Monographs, No. 441. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ^ a b Martin Tompa, Schnapsen and Sixty-Six Rules Variants. 31 March 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ Martin Tompa, The Schnapsen Log, Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ Martin Tompa, Winning Schnapsen: From Card Play Basics to Expert Strategy, 2015. ISBN 978-1515377368

- ^ Dick 1868, p. 173.

Literature

[edit]- Albrecht, Karl (1881). Die Leipziger Mundart. Leipzig: Arnold.

- Corvinus, Gottlieb Sigmund, alias "Amaranthes" (1715). Nutzbares, galantes und curiöses Frauenzimmer-Lexicon. Leipzig: Gleditsch.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dick, William Brisbane (1868). The Modern Pocket Hoyle: containing all the games of skill and chance. New York: Dick & Fitzgerald.

- Parlett, David (1996). Oxford Dictionary of Card Games. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-869173-4.

- Parlett, David (2008). The Penguin Book of Card Games. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-141-03787-5.

- Pöppel, Karl Ignaz (1960). "Die sog. Urschrift aus dem Jahre 1681 über die Entstehung des Paderborner 66-Spiels im Lichte Paderborner Geschichtsquellen" in Westfälische Zeitschrift 110.

- Stolz, Aloys (1901). Geschichte der Stadt Pforzheim. Städt. Tagblatts.

- von Thalberg, Baron F. (1860). Der Perfekte Kartenspieler. Berlin: Mode.

- Tompa, Martin (2015). Winning Schnapsen, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 452 pages.