Loving v. Virginia

| Loving v. Virginia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued April 10, 1967 Decided June 12, 1967 | |

| Full case name | Richard Perry Loving, Mildred (Jeter) Loving v. Virginia |

| Citations | 388 U.S. 1 (more) 87 S. Ct. 1817; 18 L. Ed. 2d 1010; 1967 U.S. LEXIS 1082 |

| Argument | Oral argument |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Defendants convicted, Caroline County Circuit Court (January 6, 1959); motion to vacate judgment denied, Caroline County Circuit Court (January 22, 1959); affirmed in part, reversed and remanded, 147 S.E.2d 78 (Va. 1966); cert. granted, 385 U.S. 986 (1966). |

| Holding | |

| Virginia's statutory scheme to prevent marriages between persons solely on the basis of racial classifications held to violate the Equal Protection Clause and Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Warren, joined by unanimous |

| Concurrence | Stewart |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. amend. XIV; Va. Code §§ 20–58, 20–59 | |

This case overturned a previous ruling or rulings | |

| Pace v. Alabama (1883) | |

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967), was a landmark civil rights decision of the U.S. Supreme Court that ruled that laws banning interracial marriage violate the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.[1][2] Beginning in 2013, the decision was cited as precedent in U.S. federal court decisions ruling that restrictions on same-sex marriage in the United States were unconstitutional, including in the Supreme Court decision Obergefell v. Hodges (2015).[3]

The case involved Richard Loving, a white man, and his wife Mildred Loving, a person of color.[a] In 1959, the Lovings were sentenced to prison for violating Virginia's Racial Integrity Act of 1924, which criminalized marriage between people classified as "white" and people classified as "colored". The prison sentence was suspended on condition they leave the state and not return. The Lovings moved to vacate their convictions in 1963. After unsuccessfully appealing to the Supreme Court of Virginia, they appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, arguing that the Racial Integrity Act was unconstitutional.

In June 1967, the Supreme Court issued a unanimous decision in the Lovings' favor that overturned their convictions and struck down Virginia's Racial Integrity Act. Virginia had argued before the Court that its law was not a violation of the Equal Protection Clause because the punishment was the same regardless of the offender's race, and therefore it "equally burdened" both whites and non-whites.[4] The Court found that the law nonetheless violated the Equal Protection Clause because it was based solely on "distinctions drawn according to race" and outlawed conduct—namely, that of getting married—that was otherwise generally accepted and that citizens were free to do.[4] The Court's decision ended all race-based legal restrictions on marriage in the United States.

Background

[edit]Anti-miscegenation laws in the United States

[edit]Anti-miscegenation laws had been in place in certain states since the colonial period. During the Reconstruction era in 1865, the Black Codes across the seven states of the lower South made interracial marriage illegal. The new Republican legislatures in six states repealed the restrictive laws. By 1894, when the Democratic Party in the South returned to power, restrictions were reimposed.[5]

A major concern was how to draw the line between black and white in a society in which white men had many children with enslaved black women. On the one hand, a person's reputation as black or white was usually what mattered in practice. On the other hand, most laws used a "one drop of blood" rule, which meant that one black ancestor made a person black in the view of the law.[6] In 1967, 16 states still retained anti-miscegenation laws, mainly in the American South.[7]

Plaintiffs

[edit]Mildred Delores Loving was the daughter of Musial (Byrd) Jeter and Theoliver Jeter.[8] She self-identified as Indian-Rappahannock,[9] but was also reported as being of Cherokee, Portuguese, and black American ancestry.[10][11] During the trial, it seemed clear that she identified herself as Black, and her lawyer claimed that was how she described herself to him. However, upon her arrest, the police report identified her as "Indian" and by 2004, she denied having any Black ancestry.[12]

Richard Perry Loving was a white man, the son of Lola (Allen) Loving and Twillie Loving. Their families both lived in Caroline County, Virginia, which adhered to strict Jim Crow segregation laws, but their town of Central Point had been a visible mixed-race community since the 19th century.[13] The couple met in high school and fell in love.

Mildred became pregnant, and in June 1958, the couple traveled to Washington, D.C. to marry, thereby evading Virginia's Racial Integrity Act of 1924, which made marriage between whites and non-whites a crime.[14] A few weeks after they returned to Central Point, local police raided their home in the early morning hours of July 11, 1958, hoping to find them having sex, given that interracial sex was then also illegal in Virginia.[15] When the officers found the Lovings sleeping in their bed, Mildred pointed out their marriage certificate on the bedroom wall. They were told the certificate was not valid in Virginia.[16]

Criminal proceedings

[edit]The Lovings were charged under Section 20-58 of the Virginia Code, which prohibited interracial couples from being married out of state and then returning to Virginia, and Section 20-59, which classified miscegenation as a felony, punishable by a prison sentence of between one and five years.[17]

On January 6, 1959, the Lovings pleaded guilty to "cohabiting as man and wife, against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth". They were sentenced to one year in prison, with the sentence suspended on condition that the couple leave Virginia and not return together for at least 25 years. After their conviction, the couple moved to the District of Columbia.[18]

Appellate proceedings

[edit]In 1963,[19] frustrated by their inability to travel together to visit their families in Virginia, as well as their social isolation and financial difficulties in Washington, Mildred Loving wrote in protest to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy.[20] Kennedy referred her to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).[21] The ACLU assigned volunteer cooperating attorneys Bernard S. Cohen and Philip J. Hirschkop, who filed a motion on behalf of the Lovings in Virginia's Caroline County Circuit Court, that requested the court to vacate the criminal judgments and set aside the Lovings' sentences on the grounds that the Virginia miscegenation statutes ran counter to the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause.[22]

On October 28, 1964, after waiting almost a year for a response to their motion, the ACLU attorneys filed a federal class action lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. This prompted the county court judge in the case, Leon M. Bazile (1890–1967), to issue a ruling on the long-pending motion to vacate. Echoing Johann Friedrich Blumenbach's 18th-century interpretation of race, Bazile denied the motion with the words:

Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents. And but for the interference with his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.[23]

On January 22, 1965, a three-judge district court panel postponed decision on the federal class-action case while the Lovings appealed Judge Bazile's decision on constitutional grounds to the Virginia Supreme Court. On March 7, 1966, Justice Harry L. Carrico (later Chief Justice of the Court) wrote an opinion for the court upholding the constitutionality of the anti-miscegenation statutes.[24] Carrico cited as authority the Virginia Supreme Court's decision in Naim v. Naim (1955) and ruled that criminalization of the Lovings' marriage was not a violation of the Equal Protection Clause, because both the white and the non-white spouse were punished equally for miscegenation, a line of reasoning that echoed that of the United States Supreme Court in 1883 in Pace v. Alabama.[25] However, the court did find the Lovings' sentences to be unconstitutionally vague, ordering that they be resentenced in the Caroline County Circuit Court.

The Lovings, still supported by the ACLU, appealed the state supreme court's decision to the Supreme Court of the United States, where Virginia was represented by Robert McIlwaine of the state's attorney general's office. The Supreme Court agreed on December 12, 1966, to accept the case for final review. The Lovings did not attend the oral arguments in Washington,[26] but one of their lawyers, Bernard S. Cohen, conveyed the personal message he had been given by Richard Loving: "Mr. Cohen, tell the Court I love my wife, and it is just unfair that I can't live with her in Virginia."[27][28]

Precedents

[edit]

Before Loving v. Virginia, there had been several cases on the subject of interracial sexual relations. Within the state of Virginia, on October 3, 1878, in Kinney v. The Commonwealth, the Supreme Court of Virginia ruled that the marriage legalized in Washington, D.C. between Andrew Kinney, a black man, and Mahala Miller, a white woman, was "invalid" in Virginia.[29] In the national case of Pace v. Alabama (1883), the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the conviction of an Alabama couple for interracial sex, affirmed on appeal by the Alabama Supreme Court, did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment.[30] Interracial marital sex was deemed a felony, whereas extramarital sex ("adultery or fornication") was only a misdemeanor.[31]

On appeal, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the criminalization of interracial sex was not a violation of the Equal Protection Clause because whites and non-whites were punished in equal measure for the offense of engaging in interracial sex. The court did not need to affirm the constitutionality of the ban on interracial marriage that was also part of Alabama's anti-miscegenation law, since the plaintiff, Mr. Pace, had chosen not to appeal that section of the law. After Pace v. Alabama, the constitutionality of anti-miscegenation laws banning marriage and sex between whites and non-whites remained unchallenged until the 1920s.[31]

In Kirby v. Kirby (1921), Joe R. Kirby asked the state of Arizona for an annulment of his marriage. He charged that his marriage was invalid because his wife was of "negro" descent, thus violating the state's anti-miscegenation law. The Arizona Supreme Court judged Mayellen Kirby's race by observing her physical characteristics and determined that she was of mixed race, therefore granting Joe R. Kirby's annulment.[32]

Roldan v. Los Angeles County (1933), 129 Cal. App. 267, 18 P.2d 706, was a 1930s court case in California confirming that the state's anti-miscegenation laws at the time did not bar the marriage of a Filipino and a white person.[33] However, the precedent lasted barely a week before the law was specifically amended to illegalize such marriages.[34]

In the Monks case (Estate of Monks, 4. Civ. 2835, Records of California Court of Appeals, Fourth district), the Superior Court of San Diego County in 1939 decided to invalidate the marriage of Marie Antoinette and Allan Monks because she was deemed to have "one eighth negro blood". The court case involved a legal challenge over the conflicting wills that had been left by the late Allan Monks; an old one in favor of a friend named Ida Lee, and a newer one in favor of his wife. Lee's lawyers charged that the marriage of the Monkses, which had taken place in Arizona, was invalid under Arizona state law because Marie Antoinette was "a Negro" and Alan had been white. Despite conflicting testimony by various expert witnesses, the judge defined Marie Antoinette Monks' race by relying on the anatomical "expertise" of a surgeon. The judge ignored the arguments of an anthropologist and a biologist that it was impossible to tell a person's race from physical characteristics.[35]

Monks then challenged the Arizona anti-miscegenation law itself, taking her case to the California Court of Appeals, Fourth District. Monks' lawyers pointed out that the anti-miscegenation law effectively prohibited Monks as a mixed-race person from marrying anyone: "As such, she is prohibited from marrying a negro or any descendant of a negro, a Mongolian or an Indian, a Malay or a Hindu, or any descendants of any of them. Likewise ... as a descendant of a negro she is prohibited from marrying a Caucasian or a descendant of a Caucasian." The Arizona anti-miscegenation statute thus prohibited Monks from contracting a valid marriage in Arizona and was therefore an unconstitutional constraint on her liberty. However, the court dismissed this argument as inapplicable, because the case presented involved not two mixed-race spouses but a mixed-race and a white spouse: "Under the facts presented the appellant does not have the benefit of assailing the validity of the statute."[36] Dismissing Monks' appeal in 1942, the United States Supreme Court refused to reopen the issue.[36]

The turning point came with Perez v. Sharp (1948), also known as Perez v. Lippold. In Perez, the Supreme Court of California ruled that California's ban on interracial marriage violated the Fourteenth Amendment of the Federal Constitution.[37]

Supreme Court decision

[edit]

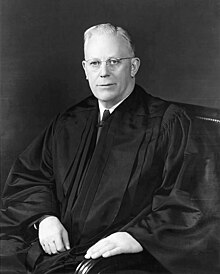

On June 12, 1967, the Supreme Court issued a unanimous 9–0 decision in favor of the Lovings. The Court's opinion was written by chief justice Earl Warren, and all the justices joined it.[b]

The Court first addressed whether Virginia's Racial Integrity Act violated the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause, which reads: "nor shall any State ... deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." Virginia state officials had argued that the Act did not violate the Equal Protection Clause because it "equally burdened" both whites and non-whites, reasoning that the punishment for violating the statute was the same regardless of the offender's race; for example, a white person who married a black person was subject to the same penalties as a black person who married a white person. The Court had accepted this "equal application" argument 84 years earlier in its 1883 decision Pace v. Alabama, but it rejected the argument in Loving.[39]

[W]e reject the notion that the mere "equal application" of a statute containing racial classifications is enough to remove the classifications from the Fourteenth Amendment's proscription of all invidious racial discriminations ....

...

The State finds support for its "equal application" theory in the decision of the Court in Pace v. Alabama. ... However, as recently as the 1964 Term, in rejecting the reasoning of that case, we stated "Pace represents a limited view of the Equal Protection Clause which has not withstood analysis in the subsequent decisions of this Court."

— Loving, 388 U.S. at 8, 10 (citations omitted).[40]

The Court said that because Virginia's Racial Integrity Act used race as a basis to impose criminal culpability, the Equal Protection Clause required the Court to strictly scrutinize whether the Act was constitutional:

There can be no question but that Virginia's miscegenation statutes rest solely upon distinctions drawn according to race. The statutes proscribe generally accepted conduct if engaged in by members of different races. Over the years, this Court has consistently repudiated "[d]istinctions between citizens solely because of their ancestry" as being "odious to a free people whose institutions are founded upon the doctrine of equality." At the very least, the Equal Protection Clause demands that racial classifications, especially suspect in criminal statutes, be subjected to the "most rigid scrutiny."

— Loving, 388 U.S. at 11 (alteration in original) (citations omitted).

The Court applied the strict scrutiny standard of review to the Racial Integrity Act and concluded it had no discernible purpose other than "invidious racial discrimination" that was designed to "maintain White Supremacy". The Court therefore ruled that the Act violated the Equal Protection Clause:[41]

There is patently no legitimate overriding purpose independent of invidious racial discrimination which justifies this classification. The fact that Virginia prohibits only interracial marriages involving white persons demonstrates that the racial classifications must stand on their own justification, as measures designed to maintain White Supremacy. We have consistently denied the constitutionality of measures which restrict the rights of citizens on account of race. There can be no doubt that restricting the freedom to marry solely because of racial classifications violates the central meaning of the Equal Protection Clause.

— Loving, 388 U.S. at 11–12.[40]

The Court ended its opinion with a short section holding that Virginia's Racial Integrity Act also violated the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause.[42] The Court said that the freedom to marry is a fundamental constitutional right, and it held that depriving Americans of it on an arbitrary basis such as race was unconstitutional:[42]

These statutes also deprive the Lovings of liberty without due process of law in violation of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The freedom to marry has long been recognized as one of the vital personal rights essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men.

Marriage is one of the "basic civil rights of man," fundamental to our very existence and survival. To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications embodied in these statutes, classifications so directly subversive of the principle of equality at the heart of the Fourteenth Amendment, is surely to deprive all the State's citizens of liberty without due process of law.— Loving, 388 U.S. at 12 (citations omitted).[43]

The Court ended by ordering that the Lovings' convictions be reversed.

Effects

[edit]For interracial marriage

[edit]Despite the Supreme Court's decision, anti-miscegenation laws remained on the books in several states, although the decision had made them unenforceable. State judges in Alabama continued to enforce its anti-miscegenation statute until 1970, when the Nixon administration obtained a ruling from a U.S. District Court in United States v. Brittain.[44][45] In 2000, Alabama became the last state to adapt its laws to the Supreme Court's decision, when 60% of voters endorsed a constitutional amendment, Amendment 2, that removed anti-miscegenation language from the state constitution.[46]

After Loving v. Virginia, the number of interracial marriages continued to increase across the United States[47] and in the South. In Georgia, for instance, the number of interracial marriages increased from 21 in 1967 to 115 in 1970.[48] At the national level, 0.4% of marriages were interracial in 1960, 2.0% in 1980,[49] 12% in 2013,[50] and 16% in 2015, almost 50 years after Loving.[51]

For same-sex marriage

[edit]Loving v. Virginia was discussed in the context of the public debate about same-sex marriage in the United States.[52]

In Hernandez v. Robles (2006), the majority opinion of the New York Court of Appeals—that state's highest court—declined to rely on the Loving case when deciding whether a right to same-sex marriage existed, holding that "the historical background of Loving is different from the history underlying this case."[53] In the 2010 federal district court decision in Perry v. Schwarzenegger, overturning California's Proposition 8 which restricted marriage to opposite-sex couples, Judge Vaughn R. Walker cited Loving v. Virginia to conclude that "the [constitutional] right to marry protects an individual's choice of marital partner regardless of gender".[54] On narrower grounds, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed.[55][56]

In June 2007, on the 40th anniversary of the Supreme Court's decision in Loving, Mildred Loving issued a statement in support of same-sex marriage.[57][58][59]

Up until 2014, five U.S. Courts of Appeals considered the constitutionality of state bans on same-sex marriage. In doing so they interpreted or used the Loving ruling differently:

- The Fourth and Tenth Circuits used Loving along with other cases like Zablocki v. Redhail[60] and Turner v. Safley[61] to demonstrate that the U.S. Supreme Court has recognized a "fundamental right to marry" that a state cannot restrict unless it meets the court's "heightened scrutiny" standard. Using that standard, both courts struck down state bans on same-sex marriage.[62][63]

- Two other courts of appeals, the Seventh and Ninth Circuits, struck down state bans on the basis of a different line of argument. Instead of "fundamental rights" analysis, they reviewed bans on same-sex marriage as discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. The former cited Loving to demonstrate that the Supreme Court did not accept tradition as a justification for limiting access to marriage.[64] The latter cited Loving as quoted in United States v. Windsor on the question of federalism: "state laws defining or regulating marriage, of course, must respect the constitutional rights of persons".[65]

- The only Court of Appeals to uphold state bans on same-sex marriage, the Sixth Circuit, said that when the Loving decision discussed marriage it was referring only to marriage between persons of the opposite sex.[66]

In Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), the Supreme Court invoked Loving, among other cases, as precedent for its holding that states are required to allow same-sex marriages under both the Equal Protection Clause and the Due Process Clause of the Constitution.[3] The court's decision in Obergefell cited Loving nearly a dozen times, and was based on the same principles – equality and an unenumerated right to marriage. During oral argument, the eventual author of the majority opinion, Justice Anthony Kennedy, noted that the ruling holding racial segregation unconstitutional and the ruling holding bans on interracial marriage unconstitutional (Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 and Loving v. Virginia in 1967, respectively) were made about 13 years apart, much like the ruling holding bans on same-sex sexual activity unconstitutional and the eventual ruling holding bans on same-sex marriage unconstitutional (Lawrence v. Texas in 2003 and Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015, respectively).[67]

Codification

[edit]In 2022, Congress codified the Supreme Court's decisions in Loving and Obergefell in federal law by passing the Respect for Marriage Act. This act requires the U.S. federal government and all U.S. states and territories (though not tribes) to recognize the validity of same-sex and interracial civil marriages in the United States.[68]

In popular culture

[edit]

In the United States, June 12, the date of the decision, has become known as Loving Day, an annual unofficial celebration of interracial marriages. In 2014, Mildred Loving was honored as one of the Library of Virginia's "Virginia Women in History".[69] In 2017, the Virginia Department of Historic Resources dedicated a state historical marker, which tells the story of the Lovings, outside the Patrick Henry Building in Richmond – the former site of the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals.[70]

The story of the Lovings became the basis of several films:

- The first, Mr. and Mrs. Loving (1996), was written and directed by Richard Friedenberg and starred Lela Rochon, Timothy Hutton, and Ruby Dee.[71] According to Mildred Loving, "not much of it was very true. The only part of it right was I had three children."[72][73]

- Nancy Buirski's documentary The Loving Story, premiered on HBO in February 2012[74][75] and won a Peabody Award that year.[76]

- Loving, a dramatized telling of the story based on Buirski's documentary, was released in 2016. It was directed by Jeff Nichols and starred Ruth Negga and Joel Edgerton as the Lovings. Negga received an Academy Award nomination for her performance.[77]

- A four-part film, The Loving Generation, premiered on Topic.com in February 2018. Directed and produced by Lacey Schwartz Delgado and Mehret Mandefro, it explores the lives of biracial children born after the Loving decision.[78][79][80]

In music, Nanci Griffith's 2009 album The Loving Kind is named for the Lovings and includes a song about them. Satirist Roy Zimmerman's 2009 song "The Summer of Loving" is about the Lovings and their 1967 case.[81] The title is a reference to the Summer of Love.

A 2015 novel by the French journalist Gilles Biassette, L'amour des Loving ("The Love of the Lovings", ISBN 978-2917559598), recounts the life of the Lovings and their case.[82] A photo-essay about the couple by Grey Villet, created just before the case, was republished in 2017.[83]

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Mildred Loving's precise racial background is not fully clear. Most sources describe her as black, but she denied being black and often said she was Native American. See the Plaintiffs section for details.

- ^ The decision also includes a very short concurring opinion—only two sentences long—written by justice Potter Stewart. Stewart wrote that, in his opinion, no state criminal law could be valid "which makes the criminality of an act depend upon the race of the actor" (as he wrote in his concurrence in McLaughlin v. Florida, a similar case in 1964), a standard which reflects justice John Marshall Harlan's dissent in 1896's Plessy v. Ferguson.[38]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967)

- ^ Nowak & Rotunda (2012), § 18.28(a), pp. 80–81.

- ^ a b Obergefell v. Hodges, No. 14-556, 576 U.S. ___ (2015)

- ^ a b Chemerinsky (2019), § 9.3.1, p. 757.

- ^ Wallenstein, Peter (August 16, 2006). "Reconstruction, Segregation, and Miscegenation: Interracial Marriage and the Law in the Lower South, 1865–1900". American Nineteenth Century History. 6: 57–76. doi:10.1080/14664650500121827. S2CID 144811039.

On the eve of Congressional Reconstruction, all seven states of the Lower South had laws against interracial marriage. During the Republican interlude that began in 1867–68, six of the seven states (all but Georgia) suspended those laws, whether through judicial invalidation or legislative repeal. Yet by 1894 all six had restored such bans.

- ^ Peter Wallenstein, "Reconstruction, Segregation, and Miscegenation: Interracial Marriage and the Law in the Lower South, 1865–1900." American Nineteenth Century History 6#1 (2005): 57–76.

- ^ Loving, 388 U.S. at 6.

- ^ "Mildred Loving obituary". Archived from the original on October 27, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- ^ "What You Didn't Know About Loving v. Virginia". Time. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ^ Lawing, Charles B. "Loving v. Virginia and the Hegemony of 'Race'" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 4, 2007. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

- ^ Walker, Dionne (June 10, 2007). "Pioneer of interracial marriage looks back". Associated Press. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ^ "50 Years Later, The Couple At The Heart of Loving v. Virginia Still Stirs Controversy". GBH. June 12, 2017. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ^ Staples, Brent (May 14, 2008). "Loving v. Virginia and the Secret History of Race". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ "Racial Integrity Laws (1924–1930)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Archived from the original on November 15, 2015. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ^ "Mildred Loving – Civil Rights Activist – Biography.com". Biography.com. A&E Television Networks, LLC. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ "The Loving Couple". The Attic. November 16, 2019. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ^ Robbins, Rohn (April 28, 2020). "Robbins: How Loving vs Virginia dealt a major blow to segregation". Vail Daily. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ Loving, 388 U.S. at 3 ("On January 6, 1959, the Lovings pleaded guilty to the charge and were sentenced to one year in jail; however, the trial judge suspended the sentence for a period of 25 years on the condition that the Lovings leave the State and not return to Virginia together for 25 years ... After their convictions, the Lovings took up residence in the District of Columbia.")

- ^ Williams, Joe. "The Arc Of Loving". Richmond Magazine. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

- ^ "Mildred Loving, Key Figure in Civil Rights Era, Dies". PBS Online News Hour. May 6, 2008. Archived from the original on June 13, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ Douglas, Martin (May 6, 2008). "Mildred Loving, Who Battled Ban on Mixed-Race Marriage, Dies at 68". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 1, 2016.

- ^ Jones, Christina Violeta (February 25, 2014). "Virginia is for the Lovings". Rediscovering Black History. National Archives. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ "Opinion of Judge Bazile in Commonwealth v. Loving (January 22, 1965)". www.encyclopediavirginia.org. Archived from the original on November 28, 2016. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- ^ "Loving v. Commonwealth (March 7, 1966)". www.encyclopediavirginia.org. Archived from the original on September 10, 2015. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ^ Loving v. Commonwealth, 206 Va. 924 (1966).

- ^ Sheppard, Kate (February 13, 2012). "'The Loving Story': How an Interracial Couple Changed a Nation". Mother Jones. Archived from the original on February 20, 2017.

- ^ "Loving v. Virginia oral argument transcript". Archived from the original on November 15, 2016. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- ^ "Loving v. Virginia (1967)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Archived from the original on December 14, 2012.

- ^ Brown, DeNeen (June 11, 2017). "Before Loving v. Virginia, another interracial couple fought in court for their marriage". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ Pace v. Alabama, 106 U.S. 583 (1883)

- ^ a b Pinsker, Matthew (June 15, 2017). "The history behind Loving v. Virginia". Interactive Constitution. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ Pascoe 1996, pp. 49–51

- ^ Moran, Rachel F. (2003). Interracial intimacy: the regulation of race & romance (Paperback ed.). Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-53663-7.

- ^ Baldoz, Rick (2011). The third Asiatic invasion: empire and migration in Filipino America, 1898-1946. Nation of newcomers: immigrant history as American history. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-9108-0. OCLC 630468381.

- ^ Pascoe 1996, p. 56

- ^ a b Pascoe 1996, p. 60

- ^ "Perez v Sharp". Justia. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ^ Schoff, Rebecca (2009). "Note: Deciding on Doctrine: Anti-Miscegnation Statutes and the Development of Equal Protection Analysis". Virginia Law Review. 95 (3): 627–665. Archived from the original on December 2, 2019. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- ^ Nowak & Rotunda (2012), § 18.8(d)(ii)(4).

- ^ a b Quoted in part in Chemerinsky (2019), § 9.3.1, p. 757.

- ^ Nowak & Rotunda (2012), § 18.28(a), pp. 80–81.

- ^ a b Chemerinsky (2019), § 10.2.1, p. 863.

- ^ Quoted in Chemerinsky (2019), § 10.2.1, p. 863.

- ^ United States v. Brittain, 319 F. Supp. 1058 (N.D. Ala. 1970).

- ^ Rosenthal, Jack (December 4, 1970). "Government Seeks to Allow A Mixed Marriage in Alabama" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- ^ Sengupta, Somini (November 12, 2000). "November 5–11; Marry at Will". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 21, 2009. Retrieved May 27, 2009.

The margin by which the measure passed was itself a statement. A clear majority, 60 percent, voted to remove the miscegenation statute from the state constitution, but 40 percent of Alabamans – nearly 526,000 people – voted to keep it.

- ^ "Interracial marriage flourishes in U.S." NBC News. April 15, 2007. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- ^ Aldridge, The Changing Nature of Interracial Marriage in Georgia: A Research Note, 1973

- ^ "Table 1. Race of Wife by Race of Husband: 1960, 1970, 1980, 1991, and 1992". census.gov. U.S. Bureau of the Census. July 5, 1994. Archived from the original on March 4, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ "Interracial marriage: Who is 'marrying out'?". Pew Research Center. June 12, 2015. Archived from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- ^ "Intermarriage across the U.S. by metro area". Pew Research Center's Social & Demographic Trends Project. May 18, 2017. Archived from the original on June 6, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2017.

- ^ Trei, Lisa (June 13, 2007). "Loving v. Virginia provides roadmap for same-sex marriage advocates". News.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on December 13, 2012. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- ^ Hernandez v. Robles, 855 N.E.3d 1 (N.Y. 2006).

- ^ Perry v. Schwarzenegger, 704 F. Supp. 2d 921 (N.D. Cal. 2010).

- ^ Nagoruney, Adam (February 7, 2012). "Court Strikes Down Ban on Gay Marriage in California". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 11, 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2012.

- ^ Perry v. Brown, 671 F.3d 1052 (9th Cir. 2012).

- ^ "Mildred Loving Endorses Marriage Equality for Same-Sex Couples". American Constitution Society. June 15, 2007. Archived from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- ^ Douglas Martin (June 18, 2007). "Mildred Loving, 40 Years Later". The Atlantic. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- ^ Douglas Martin (May 6, 2008). "Mildred Loving, Who Battled Ban on Mixed-Race Marriage, Dies at 68". New York Times. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- ^ Zablocki v. Redhail, 434 U.S. 374 (1978)

- ^ Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78 (1987)

- ^ Bostic v. Shaefer, 760 F.3d 352, 376 (4th Cir. 2014) ("In Loving v. Virginia, the Supreme Court invalidated a Virginia law that prohibited white individuals from marrying individuals of other races. The Court explained that '[t]he freedom to marry has long been recognized as one of the vital personal rights essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men' and that no valid basis justified the Virginia law's infringement of that right. [citations omitted]").

- ^ Kitchen v. Herbert, 755 F.3d 1193 (10th Cir. 2014).

- ^ Baskin v. Bogan, 766 F.3d 648 (7th Cir. 2014).

- ^ Latta v. Otter, 771 F.3d 456, 474 (2014).

- ^ DeBoer v. Snyder, 772 F.3d 388, 411 (6th Cir. 2014) ("Matters do not change because Loving v. Virginia held that 'marriage' amounts to a fundamental right. ... In referring to 'marriage' rather than "opposite-sex marriage", Loving confirmed only that 'opposite-sex marriage' would have been considered redundant, not that marriage included same-sex couples. Loving did not change the definition. [citations omitted]").

- ^ Amar, Akhil Reed (July 6, 2015). "Anthony Kennedy and the Ghost of Earl Warren". Slate. Archived from the original on July 7, 2015. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

- ^ Dwyer, Devin (December 13, 2022). "What the Respect for Marriage Act does and doesn't do". ABC News. Retrieved July 11, 2024.

- ^ "Virginia Women in History: Mildred Delores Jeter Loving". Library of Virginia. Archived from the original on March 21, 2015. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ^ Wise, Scott (June 8, 2017). "Virginia to honor interracial marriage with state historical marker". WTVR.com. Archived from the original on June 8, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2017.

- ^ *Mr. & Mrs. Loving at IMDb

- ^ Walker, Dionne (June 10, 2007). "Pioneer of interracial marriage looks back". USAToday.com. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ^ "40 years of interracial marriage: Mildred Loving reflects on breaking the color barrier". International Herald-Tribune. Associated Press. June 9, 2007. Archived from the original on May 8, 2008. Retrieved April 28, 2008.

- ^ Stanley, Alessandra (February 13, 2012). "Scenes From a Marriage That Segregationists Tried to Break Up". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 14, 2012.

- ^ The Loving Story Archived 2012-06-12 at the Wayback Machine, accessed March 25, 2015

- ^ 72nd Annual Peabody Awards Archived 2014-09-11 at the Wayback Machine, May 2013.

- ^ McDermott, Maeve (January 24, 2017). "Get to Know Ruth Negga, the Oscar-Nominated Breakout Star of "Loving"". USA Today. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ^ "The Loving Generation". Topic.com. Archived from the original on February 17, 2018. Retrieved February 18, 2018.

- ^ Branigin, Anne (February 10, 2018). "The Loving Generation Explores the Lives of Biracial Children Born After Mixed-Race Marriages Were Legalized". The Root. Archived from the original on February 16, 2018. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ Holmes, Anna (February 10, 2018). "Black With (Some) White Privilege". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 14, 2018. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ Altman, Ross (July 12, 2017). "Roy Zimmerman: Rezist". FolkWorks. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ Mahuzier, Marc (June 21, 2015). "L'amour en noir et blanc". Ouest-France. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ^ Villet, Barbara; Villet, Grey (February 14, 2017). The Lovings: An Intimate Portrait. Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 978-1616895563.

Bibliography

[edit]- Chemerinsky, Erwin (2019). Constitutional Law: Principles and Policies (6th ed.). New York: Wolters Kluwer. ISBN 978-1-4548-9574-9.

- Nowak, John E.; Rotunda, Ronald D. (2012). Treatise on Constitutional Law: Substance and Procedure (5th ed.). Eagan, Minnesota: West Thomson/Reuters. OCLC 798148265.

Further reading

[edit]- Aldridge, Delores (1973). "The Changing Nature of Interracial Marriage in Georgia: A Research Note". Journal of Marriage and the Family. 35 (4): 641–642. doi:10.2307/350877. JSTOR 350877.

- Annella, M. (1967). "Interracial Marriages in Washington, D.C.". Journal of Negro Education. 36 (4): 428–433. doi:10.2307/2294264. JSTOR 2294264.

- Barnett, Larry (1963). "Research on International and Interracial Marriages". Marriage and Family Living. 25 (1): 105–107. doi:10.2307/349019. JSTOR 349019.

- Brower, Brock; Kennedy, Randall L. (2003). "'Irrepressible Intimacies'. Review of Interracial Intimacies: Sex, Marriage, Identity, and Adoption, by Randall L. Kennedy". Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. 40 (40): 120–124. doi:10.2307/3134064. JSTOR 3134064.

- Christopher Leslie (2004) Justice Alito's Dissent in Loving v. Virginia, University of California, p. 1564.

- Coolidge, David Orgon (1998). "Playing the Loving Card: Same-Sex Marriage and the Politics of Analogy". BYU Journal of Public Law. 12: 201–238.

- DeCoste, F. C. (2003). "The Halpren Transformation: Same-Sex Marriage, Civil Society, and the Limits of Liberal Law". Alberta Law Review. 41 (2): 619–642. doi:10.29173/alr1338.

- Dorothy Robert (2014) Loving v. Virginia as a civil rights decision Archived April 6, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, p. 177.

- Foeman, Anita Kathy & Nance, Teresa (1999). "From Miscegenation to Multiculturalism: Perceptions and Stages of Interracial Relationship Development". Journal of Black Studies. 29 (4): 540–557. doi:10.1177/002193479902900405. S2CID 143739003.

- Hopkins, C. Quince (2004). "Variety in U.S Kinship Practices, Substantive Due Process Analysis and the Right to Marry". BYU Journal of Public Law. 18: 665–679.

- Kalmijn, Matthijs (1998). "Intermarriage and Homogamy: Causes, Patterns, Trends". Annual Review of Sociology. 24 (24): 395–421. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.395. hdl:1874/13605. PMID 12321971. S2CID 11955842.

- Koppelman, Andrew (1988). "The Miscegenation Analogy: Sodomy Law as Sex Discrimination". Yale Law Journal. 98 (1): 145–164. doi:10.2307/796648. JSTOR 796648.

- Newbeck, Phyl (2004). Virginia hasn't always been for lovers.

- Pascoe, Peggy (1996). "Miscegenation Law, Court Cases, and Ideologies of 'Race' in Twentieth-Century America". Journal of American History. 83 (1): 44–69. doi:10.2307/2945474. JSTOR 2945474.

- Pratt, Robert A. (1997). "Crossing the color line: A historical assessment and personal narrative of Loving v. Virginia". Howard Law Journal. 41: 229.

- Villet, Grey (2017). The Lovings: An Intimate Portrait.

- Wadlington, Walter (November 1967). Domestic Relations.

- Wallenstein, Peter (2014). Race, Sex, and the Freedom to Marry: Loving v. Virginia. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-2000-5.

- Wildman, Stephanie (2002). "Interracial Intimacy and the Potential for Social Change: Review of Interracial Intimacy: The Regulation of Race and Romance by Rachel F. Moran". Berkeley Women's Law Journal. 17: 153–164. doi:10.2139/ssrn.309743.

- Yancey, George & Yancey, Sherelyn (1998). "Interracial Dating: Evidence from Personal Advertisements". Journal of Family Issues. 19 (3): 334–348. doi:10.1177/019251398019003006. S2CID 145209341.

External links

[edit]Links with the text of the court's decision

[edit] Works related to Loving v. Virginia at Wikisource

Works related to Loving v. Virginia at Wikisource- Text of Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) is available from: Cornell CourtListener Findlaw Google Scholar Justia Library of Congress OpenJurist Oyez (oral argument audio)

Other external links

[edit]- A Groundbreaking Interracial Marriage; Loving v. Virginia at 40. ABC News interview with Mildred Jeter Loving & video of original 1967 broadcast. June 14, 2007.

- Resources at Oyez.org including complete audio of the oral arguments.

- Loving Decision: 40 Years of Legal Interracial Unions, National Public Radio: All Things Considered, June 11, 2007.

- The Fortieth Anniversary of Loving v. Virginia: The Legal Legacy of the Case that Ended Legal Prohibitions on Interracial Marriage, Findlaw commentary by Joanna Grossman.

- Chin, Gabriel and Hrishi Karthikeyan, (2002) Asian Law Journal, vol. 9 "Preserving Racial Identity: Population Patterns and the Application of Anti-Miscegenation Statutes to Asian Americans, 1910–1950"

- 1967 in United States case law

- 1967 in Virginia

- African-American history of Virginia

- American Civil Liberties Union litigation

- Caroline County, Virginia

- Civil rights movement case law

- Interracial marriage in the United States

- June 1967 events in the United States

- Legal history of Virginia

- Mildred and Richard Loving

- Native American history of Virginia

- Race-related case law in the United States

- Rappahannock

- United States equal protection case law

- United States marriage case law

- United States racial discrimination case law

- United States substantive due process case law

- United States Supreme Court cases of the Warren Court

- United States Supreme Court cases

- United States Supreme Court decisions that overrule a prior Supreme Court decision