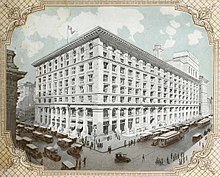

B. Altman and Company Building

| B. Altman & Company Building | |

|---|---|

Seen in 2020 from the corner of Fifth Avenue and 34th Street | |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Commercial offices, educational |

| Architectural style | Italian Renaissance Revival |

| Location | 355–371 Fifth Avenue, Manhattan, New York |

| Coordinates | 40°44′55″N 73°59′01″W / 40.74861°N 73.98361°W |

| Current tenants | City University of New York, Oxford University Press |

| Construction started | 1905 |

| Completed | 1914 |

| Opened | 1906 |

| Renovated | 1996 |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 13 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Trowbridge & Livingston |

| Main contractor | Marc Eidlitz & Son |

| Renovating team | |

| Renovating firm | Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer, Gwathmey Siegel & Associates |

| References | |

| Designated | March 12, 1985[1] |

| Reference no. | 1274 |

The B. Altman and Company Building is a commercial building in Midtown Manhattan in New York City, that formerly served as B. Altman and Company's flagship department store. It occupies an entire city block between Fifth Avenue, Madison Avenue, 34th Street, and 35th Street, directly opposite the Empire State Building, with a primary address of 355–371 Fifth Avenue.

The B. Altman and Company Building was designed by Trowbridge & Livingston in the Italian Renaissance Revival style. Most of the building is eight stories tall, though the Madison Avenue end rises to thirteen stories. It contains a facade made largely of French limestone, except at the Madison Avenue end, where the ninth through thirteenth stories and most of the Madison Avenue side are faced with white brick. The facade contains a large arcade with a colonnade at its two-story base.

Altman's was the first big department store to make the move from the Ladies' Mile shopping district to Fifth Avenue, which at the time was still primarily residential. The building was opened in stages between 1906 and 1914, due to the difficulty in acquiring real estate. The store closed in 1989 and was vacant until 1996, when it was renovated. The building was reconfigured to house the City University of New York's Graduate Center, the New York Public Library's Science, Industry and Business Library, and the Oxford University Press. The B. Altman and Company Building was made a New York City designated landmark in 1985.

Site

[edit]The B. Altman and Company Building occupies a full city block in Midtown Manhattan, bounded by Fifth Avenue on the west, 34th Street on the south, Madison Avenue on the east, and 35th Street on the north.[2] The building's land lot has a total area of 82,950 square feet (7,706 m2); it measures 197.5 feet (60.2 m) from north to south and 420 feet (130 m) from west to east.[3] Because of the topography of the region, the northern ends of the Fifth and Madison Avenue facades are slightly higher than the southern ends.[4]

The B. Altman Building is close to the Empire State Building to the southwest, 200 Madison Avenue to the north, the Church of the Incarnation to the northeast, the Collectors Club of New York to the east, and the Madison Belmont Building to the southeast.[2] It is one of several former major retail buildings on the surrounding stretch of Fifth Avenue. Within four blocks to the north are the Gorham Building at 390 Fifth Avenue, the Tiffany and Company Building at 401 Fifth Avenue, the Stewart & Company Building at 404 Fifth Avenue, and the Lord & Taylor Building at 424 Fifth Avenue.[2][5][6]

Architecture

[edit]The B. Altman and Company Building was designed by Trowbridge & Livingston in the Italian Renaissance Revival style and opened in three phases in 1906, 1911, and 1914.[7][8] The main section on Fifth Avenue, opened in 1906 and expanded in 1911, has its facade designed as an arcade.[9] The Madison Avenue annex, completed in 1914, has more design motifs than the original Fifth Avenue structure and its addition.[10] Marc Eidlitz & Son was the general contractor for the building,[11][12] and Hecla Iron Works manufactured the metalwork.[13]

The majority of the building is eight stories tall, but the Madison Avenue side rises to 13 stories.[3][14] The original section of the building contained entrances on Fifth Avenue, 34th Street, and 35th Street,[15] while the annex contained two additional entrances on Madison Avenue and 35th Street.[16]

Facade

[edit]The structure's facade was generally intended to harmonize with the designs of mansions on Fifth Avenue, which at the time of the building's completion was largely residential.[9][17] The design, across the street from the grand residence of department-store rival A. T. Stewart and diagonally across the avenue from the residence of Caroline Schermerhorn Astor, was planned to complement the surrounding palatial mansions.[9] The design used imported French limestone.[13][16] The B. Altman Building was the first commercial structure in New York City to use the material, which had previously been used only on residential buildings.[4]

The four elevations or sides are largely similar to each other. On all sides, the first two floors comprise an arcaded base, the third through sixth floors contain square windows, and the seventh and eighth floors comprise an arched arcade. The Fifth and Madison Avenue facades both contain nine bays, but the Fifth Avenue side is eight stories tall, while the Madison Avenue side is 13 stories. The 34th and 35th Street sides are both seventeen bays wide and are mostly eight stories tall, although the easternmost four bays rise to the thirteenth story.[18] The facade is mostly unchanged from the building's completion, although some spalling in the facade was patched with cast stone, and some design elements were removed or simplified.[19]

Base

[edit]On Fifth Avenue, the lowest two stories contain a colonnade with double-height engaged columns in the Ionic order, raised upon pedestals and supporting a plain architrave. The columns are largely plain, except the center four, which are fluted and flank a slightly projecting entrance portico in the center three bays. Inside each bay of the colonnade, the first- and second-floor window openings are separated by horizontal stone architraves. The windows on the first floor are large display windows while those on the second floor are semicircular Diocletian windows. In the entrance portico, small stone steps lead to the doors in each bay, which are located underneath glass turtle-shell canopies.[4] This entrance portico leads to the CUNY Graduate Center.[20]

On 34th Street, the first two stories mostly contain rectangular pilasters instead of columns. There is an entrance portico in the sixth, seventh, and eighth bays from west, with fluted columns similar to those on Fifth Avenue, though only the seventh bay has a glass canopy and stone steps. Additionally, on the first story, only the westernmost four bays and the easternmost two bays have display windows, while the other windows are wide rectangular sash windows behind a grille. A service entrance is in the eleventh and twelfth bays from west. The second floor openings are semicircular.[21]

The Madison Avenue side contains a colonnade in the center seven bays, supported by engaged plain columns. The outermost bay on either side projects slightly, with rectangular pilasters. The central bay led to the former library entrance.[21]

The 35th Street side is similar to, but less elaborate than, the 34th Street side. The westernmost three bays and the easternmost bay contain display windows, while most of the remaining bays contain rectangular sash windows behind a grille. The fourth bay from west contains a metal entrance structure that projects slightly and has a frieze running on top. There is a delivery entrance nearer the Madison Avenue end.[14]

Upper stories

[edit]The layout of the third through eighth stories is identical on Fifth Avenue, 34th Street, and 35th Street.[18] The third story has one square-headed opening in each bay and keystones above the windows, as well as a horizontal band course above the windows. The fourth through sixth stories have square-headed openings, with no keystones, and a frieze runs above the sixth floor.[4] The seventh and eighth stories are designed as a double-height arcade, similar to the base; each bay has a square-headed window under a semicircular window, separated by a transom. A heavy cornice runs above the eighth story on Fifth Avenue and on most of the 34th and 35th Street facades.[21]

The four eastern bays on 34th and 35th Streets are thirteen stories tall, though the upper five stories are made of brick instead of limestone.[22] The ninth story has two double-hung windows in each bay and is topped by a band course. The windows on the tenth and eleventh stories are recessed within a large opening; each set of windows is separated by small cast iron Ionic columns, with architraves above the tenth-story windows and a pair of small arches above the eleventh-story windows. The top two stories contain double-hung windows similar to the ninth story. A band course supported by corbels runs above the twelfth story, and a small cornice runs above the thirteenth story.[21]

On Madison Avenue, the outermost bays are faced with limestone up to the eighth story, while the inner bays and the ninth through thirteenth stories are faced with brick. The outer bays are similar in design to the easternmost bays on 34th Street. The inner bays contain double-hung window pairs on the third floor and triple-height window openings on the fourth through sixth stories. Each of the triple height openings contains a pair of Ionic columns, supporting an architrave and small pediment on the fourth floor; an architrave on the fifth floor; and brackets on the sixth floor. The seventh and eighth floors of the inner bays are designed as an arcade, similarly to on the other elevations, except that it has cast-iron columns and architrave. The ninth through thirteenth floors are the same as on the other elevations.[14]

Features

[edit]B. Altman store

[edit]There were 39 elevators in the building when completed: 22 passenger elevators, 10 employee elevators, as well as two massive truck elevators and five smaller private elevators.[16] The building also contained an electric power plant, described as the city's largest.[23] The ventilation system was able to handle intake and exhaust volumes of 20,000 cubic feet (570 m3) per minute. To accommodate packages and message deliveries, the building used an extensive system of brass tubing and canvas belting.[16]

At ground level, the building had a large entrance rotunda on Fifth Avenue as well as open-plan selling floors.[5] The rotunda had a glass dome with indirect lighting.[15][24] The glass dome was illuminated on cloudy days by electric lamps that were placed behind the dome. There were also sales galleries placed around the rotunda.[24] The rotunda was replaced with escalators in the 1930s.[5] The interiors had high ceilings: the first floor had a ceiling height of 22 feet (6.7 m) while the second and third floors had ceilings of 18 feet (5.5 m).[25]

When the store opened in 1906, its various departments were placed in the same locations as B. Altman's previous store on Sixth Avenue.[26] The first through fourth floors were used as selling floors, while the upper floors were used as workshops, offices, and stockrooms.[15] On the third floor, which sold suits and linens, there was a large room with mirrors, which could be slid aside to allow natural light.[15][24] The fourth floor had a waiting room with wooden desks and chairs, and telephones.[15] With the opening of the Madison Avenue expansion, the public areas of the store were expanded to the fifth floor,[23] which contained a women's writing room, an information bureau, telephones, and a general store.[16] The eighth floor contained the Charleston Gardens restaurant.[27] The ninth floor contained vaults for fur storage, encased in cork 4 to 5 inches (100 to 130 mm) thick. Employees' facilities, including restrooms, dining rooms, and medical aid rooms, were on the twelfth floor.[23]

Current usage

[edit]

Since its refurbishment in the 1990s, the B. Altman Building has been shared by the City University of New York (CUNY)'s Graduate Center and Oxford University Press (OUP).[9] The space of a third occupant, New York Public Library (NYPL), was sold off to several other condominium owners in the 2010s.[28]

The Graduate Center is on the Fifth Avenue side of the building. The first through seventh floors contain classrooms, student spaces, and offices.[29] The Mina Rees Library of the Graduate Center occupies parts of the building's first floor, concourse, and second floor.[30] The Graduate Center section of the building contains three performance spaces: the 389-seat Harold M. Proshansky Auditorium on the concourse, the 180-seat Baisley Powell Elebash Recital Hall on the first floor, and the 70-seat Martin E. Segal Theatre on the first floor.[29] The ground floor also houses the Amie and Tony James Gallery.[31] An eighth-floor dining room contains ceilings of 40 feet (12 m) as well as a skylight from which the Empire State Building is visible.[29][27]

On the Madison Avenue side of the building, the NYPL occupied an eight-floor condominium spanning 213,000 square feet (19,800 m2) from the 1990s.[25] The NYPL condominium was split up into four units in 2012.[28] Prior to 2020,[32] the NYPL's Science, Industry and Business Library (SIBL) occupied five floors in the building, with a research library in the basement, a lobby and circulating library at ground level, and offices on three upper levels. The branch contained various business and training centers, as well as conference rooms and stacks.[33][34] OUP occupies a five-floor condominium spanning 110,000 square feet (10,000 m2).[25]

History

[edit]Background

[edit]

B. Altman and Company originated from a store in the Lower East Side operated by the Altman family. The store was solely owned by Benjamin Altman and was located at Third Avenue and 10th Street by 1865.[35][13] The residential core of Manhattan, once concentrated in lower Manhattan, moved uptown during the late 19th century.[36] By the 1870s, stores were being established between 14th and 23rd Streets in the Ladies' Mile area, including B. Altman and Company, which opened a store at Sixth Avenue between 18th and 19th Streets.[35][36][37] Altman's Sixth Avenue store occupied a 150-by-184-foot (46 by 56 m) site in the 1870s; by the mid-1890s, the store had expanded to cover the entire 200-foot (61 m) width of the block on Sixth Avenue.[13] However, the Sixth Avenue location had become undesirable by the end of the 19th century, partially due to the shadows and noise created by the Sixth Avenue elevated line.[38][39] In addition, Altman did not own any of the land under his Sixth Avenue store; instead, he leased it from two separate sets of owners.[13]

Altman initially contemplated moving his store to Herald Square, at the northeastern corner of 34th Street and Sixth Avenue, directly across from Macy's Herald Square.[5] He ultimately decided on a site on Fifth Avenue, one block to the east, because of the presence of the Waldorf–Astoria hotel at that intersection and because Fifth Avenue was not overshadowed by an elevated line.[5][38] At the beginning of the 20th century, development was centered on Fifth Avenue north of 34th Street,[40][41] and many stores on that avenue were situated inside rebuilt 19th-century residences.[5][42]

New building

[edit]Initial land acquisition

[edit]Benjamin Altman began acquiring land for his Fifth Avenue store in 1895 or 1896, when he obtained a four-story building at the southwest corner of Fifth Avenue and 35th Street.[13][43] Altman initially did not reveal the purpose of these purchases,[38][43] as he did not want neighbors to learn of his intentions and, thus, potentially thwart the project.[13] He did not make another purchase until 1901,[43] when he was listed as the buyer of a five-story building at 365 Fifth Avenue.[44] All of these properties were acquired from separate owners, none of whom knew that Altman was buying other properties on the block.[13]

Purchases of property on the block accelerated after plans for Pennsylvania Station and Grand Central Terminal, two major transport hubs nearby, were respectively announced in 1902 and 1903.[38] By then, some landowners had begun to suspect that the buildings on the block were being sold for commercial purposes, and they either refused to sell or offered only to rent their properties.[13] The five-story building at 361 Fifth Avenue was sold in January 1904, and the buyer paid such a high price for the relatively small lot ($170,000) that the Real Estate Record and Guide presumed that the buyer was acting on Altman's behalf.[45] Altman was initially unable to acquire some holdout properties, as many owners "declined even to entertain offers" and some lessees "became as violent obstructionists as the owners themselves".[43] However, these individuals did not form any alliances to specifically prevent the building's construction.[42][10]

Plans for the new Altman's flagship building were officially announced in December 1904, after Altman had bought many of the properties on the block.[46][43][47] The Real Estate Record at the time characterized Altman's plans as having been "an open secret for some years".[42] The announcement resulted in an increase in real estate transactions on the surrounding blocks of Fifth Avenue.[48] Trowbridge and Livingston were formally selected as architects the next month. A representative for B. Altman and Company indicated that the Fifth Avenue section of the building would be completed first, followed by the Madison Avenue section.[49] At the time, the structure was planned to cost $2.5 million;[13] including the site, the project was to cost $5 million.[13] Plans for the building were filed in March 1905, and Marc Eidlitz & Son was hired as general contractor.[11][12] The same month, he paid a combined $515,000 for two houses at 3 and 5 East 34th Street. This gave him control of nearly the entire block, except the corner of Fifth Avenue and 34th Street, and the Madison Avenue frontage.[13]

Construction and opening

[edit]

In April 1905, Altman received a $4.5 million mortgage loan from the Mutual Life Insurance Company of New York, which covered several properties on the flagship's site.[50] That May, The New York Times reported that the row house at Fifth Avenue and 34th Street was still being leased by art dealer Knoedler. The lease did not expire for "five or six more years" and negotiations between Knoedler and Altman had reached an impasse.[51] Additionally, there were several incidents during construction. Three workers were killed and several were injured in a December 1905 dynamite explosion,[52][53] and there was an attempt the same month to sabotage the building's hoisting engines.[54] In January 1906, a worker was killed and six others were injured when a girder fell from the eighth floor.[55][56]

In anticipation of the new store's opening, Altman sold the old Sixth Avenue store in April 1906.[57] The first section of the Fifth Avenue building was opened on October 15, 1906, with entrances on 34th Street, 35th Street, and Fifth Avenue; the previous store on Sixth Avenue was closed at that time.[15][58] Although the original design entailed developing Knoedler's holdout lot, the initial section of the building wrapped around the lot.[10][24] Knoedler moved uptown in 1910,[24] and Trowbridge and Livingston filed plans for the second section of the building, to be erected on Knoedler's old lot, that December.[59] The section at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 34th Street opened in September 1911.[60] After the second section opened, the building had a floor area of 550,000 square feet (51,000 m2).[61]

Two landowners, Margaret A. Howard and William Waldorf Astor, owned the remaining sites on Madison Avenue.[24] Altman bought Howard's land in October 1910,[62][63][64] paying $750,000 for three lots that Howard had bought for $190,000 two decades previously. He also took a long-term lease from Astor, who was generally averse to selling off his family's land.[24] These transactions cost a total of $1.2 million[62][63] and included several townhouses.[23] Trowbridge & Livingston filed plans for the annex in June 1913, which would expand the building's floor area to 900,000 square feet (84,000 m2).[65][61] The third section was developed during the final years of Benjamin Altman's life, during which he stopped himself from social events. Though he was an avid art collector, he refused to display his art because he thought it would accidentally advertise his store.[66] When Altman died in October 1913, the buildings on Madison Avenue were being torn down.[67] He bequeathed all of his property (including the Fifth Avenue store) to his company, of which all capital stock was to be held by the Altman Foundation, essentially transferring the building to the foundation.[19][68] The final section on Madison Avenue opened on October 5, 1914.[16]

Flagship operation

[edit]

During Benjamin Altman's life, there had never been any exterior signage advertising the store, out of respect to people who lived nearby.[66] In 1924, Altman's acquired the final land lease for the building, consisting of two lots at Fifth Avenue and 34th Street. Altman's thus had ownership of all lots on the block.[69][70] The facade was renovated in 1936 after some of the limestone had deteriorated. Parts of the original facade were replaced with simplified designs; for instance, portions of the cornice on 34th and 35th Streets were removed.[71][72] Alteration plans for the building were filed in 1938, with an estimated cost of $250,000.[73] The renovations, in preparation for the 1939 New York World's Fair, involved the removal of the rotunda for additional selling space, as well as new departments designed by H. T. Williams.[74][75] In 1940, Altman's reopened its refurbished third floor, and six departments were added to the Fifth Avenue side, in what was referred to as the "Fifth Avenue Walk".[76]

Rumors of a new structure on the site started circulating in 1970, to which Altman's distributed letters announcing their intention to stay in the same location.[77] The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) started considering the building for landmark status in 1982.[72] The LPC held hearings to discuss possible landmark status for the building, but Altman's had opposed the designation at the time.[78] In November 1984, the store's owner Altman Foundation indicated its intention to downsize the Altman's location and sell off the upper floors at the Madison Avenue end to an investment syndicate, which would convert the space to residences and offices.[71][79] The downsizing was required because of New York state legislation that forced the Altman Foundation to divest of some of its business holdings or pay a fine.[71][80] The plans entailed removing 25,000 square feet (2,300 m2) of retail space on each of seven floors,[81] but these removals did not occur.[71]

On March 12, 1985, the LPC designated the B. Altman and Company Building's exterior as a New York City landmark.[1][82] The syndicate that owned the building, KMO-361 Realty Associates, was named for the initials of its principals, Earle W. Kazis, Peter L. Malkin, and Morton L. Olshan, as well as the building's Fifth Avenue address.[83] The chain was acquired by L.J. Hooker in 1987, but KMO-361 continued to own the real estate.[71][84] In November 1987, KMO-361 announced plans to add six floors at the Madison Avenue end of the building. The store would occupy 405,000 square feet (37,600 m2) on the lowest five floors and there would be 550,000 square feet (51,000 m2) of office space on the upper floors.[71][85][86] Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates would also remodel the facade details to their original design, add an entrance pavilion along Madison Avenue, and add a roof pavilion above the main eight-story store.[87][88] The LPC approved the expansion plans in 1988.[5][89] Neighbors raised concerns that the Madison Avenue office addition would cast excessive shadows.[90][91]

The second floor of the store, which contained the fashion department, was remodeled in 1988. The project was planned to be the first phase of a total renovation of the building.[92] The renovation stalled due to Altman's financial issues.[91] Altman's filed for bankruptcy in August 1989,[91][93] By that November, the flagship was set to close. The building had been placed at auction for one month, but no bidders made an offer for the building.[94] Altman's liquidated its merchandise,[95] and the store within the building permanently closed on December 31, 1989.[89]

Reuse

[edit]Although the B. Altman Building's landmark status prevented the store from being torn down, KMO's plans to add six stories had stalled with the announcement of the store's closure.[96] In late 1991, KMO proposed that 650,000 square feet (60,000 m2) of the building be converted to the New York Resource Center, a furniture and appliances showroom.[83][97][98] Another 200,000 square feet (19,000 m2) would be used by the New York Public Library (NYPL), which would open the Science, Industry and Business Library (SIBL) there.[83] The NYPL issued bonds to pay for the space.[99] The New York Resource Center plans were ultimately postponed indefinitely because of a lack of interest in the project. Richard P. Steinberg, one of Olshan's partners, stated in 1994 that three "significant" museums and two educational institutions had expressed interest in the building, though there was no definite commitment.[25] Several other companies expressed interest in the building's space, including Sotheby's[100] and J. C. Penney.[101]

Nearby, Oxford University Press was looking to move from their space at 200 Madison Avenue.[25] The NYPL bought an eight-floor condominium on the Madison Avenue side of the B. Altman Building in February 1993,[102] and OUP contracted to buy a five-floor condominium the following January.[25] The City University of New York (CUNY) also announced plans to move its Graduate Center to the Altman Building from the Aeolian Hall on West 42nd Street, and sell the Aeolian Hall to the State University of New York College of Optometry, which was finalized in 1995.[103]

Starting in 1996, the exterior was restored by Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer and the interior reconfigured by Gwathmey Siegel & Associates.[7][8] The OUP offices were designed by Hellmuth, Obata & Kassabaum.[25] The renovations, which cost over $170 million, involved restoring many old design elements such as the lobby porticoes, bronze elevator cabs, and cast-iron staircases.[27] The SIBL opened within the building in 1996.[104] CUNY was scheduled to move the Graduate Center there in late 1999, but the relocation was delayed due to setbacks in construction.[105] The CUNY Graduate Center moved to the B. Altman Building in 2000.[106][107]

In 2012, because of the NYPL's budgetary issues, the library arranged to sell off five of the upper floors that it had used as office space.[108] The NYPL's eight-floor condominium was divided four ways in 2012, and the five upper floors were sold that year for $60.8 million to the Church Pension Fund.[28] The NYPL announced in 2016 that the SIBL would close after the completion of an upcoming renovation of the Mid-Manhattan Library.[109] The same year, it sold the remaining office condominium unit to Seattle developer Vulcan Inc., headed by Paul Allen, for $93 million.[28] The Museum of Pop Culture, which had been founded by Allen, indicated in 2018 that it was considering opening a location in the SIBL space.[110][111] The SIBL was permanently closed after the Mid-Manhattan Library reopened in 2020 as the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library,[32] with a business center that replaced the SIBL's collection.[112]

Impact

[edit]At the building's opening, a Times critic wrote that "the store adds materially to the beauty of Fifth Avenue".[15] Altman's had been the first big department store to make the move from Ladies' Mile to Fifth Avenue, which at the time was still primarily residential.[9][10] Following Altman's example, other major stores made the move uptown to the "middle" portion of Fifth Avenue, including Best & Co., W. & J. Sloane, Lord & Taylor, Arnold Constable & Company, and Bergdorf Goodman.[9][10][a]

The B. Altman Building's stature made it a "three-ring circus", according to The New York Times.[27] The running track on the building's roof was used for training by the United States Olympic team, as depicted in the 1981 film Chariots of Fire.[27] The building was also used for exterior filming in the 2017 Amazon Studios television series The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel.[118]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Best & Co. was located at 372 Fifth Avenue;[113] W & J. Sloane at 414 Fifth Avenue;[114] Lord & Taylor at 424 Fifth Avenue;[115] Arnold Constable at 453 Fifth Avenue, now the Mid-Manhattan Library;[116] and Bergdorf Goodman at 754 Fifth Avenue.[117]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1985, p. 1.

- ^ a b c "NYCityMap". NYC.gov. New York City Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ a b "355 5 Avenue, 10016". New York City Department of City Planning. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1985, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gray, Christopher (January 28, 1990). "Streetscapes: B. Altman's; the Life and Death(?) of a Palace for the Chic". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ White, Willensky & Leadon 2010, pp. 267–268.

- ^ a b White, Willensky & Leadon 2010, p. 266.

- ^ a b New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S.; Postal, Matthew A. (2009). Postal, Matthew A. (ed.). Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1.

- ^ a b c d e f White, Willensky & Leadon 2010, p. 267.

- ^ a b c d e Landmarks Preservation Commission 1985, p. 4.

- ^ a b "Altman Building Plans Filed". Real Estate Record and Builders Guide. Vol. 75, no. 1929. March 4, 1905. p. 463 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b "New Altman Store Plans". The New York Times. March 4, 1905. p. 6. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 11, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Tauranac 1985, p. 70.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1985, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Old Friends Throng Altman's New Store; Fifth Avenue Building Crowded at Its Opening". The New York Times. October 16, 1906. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "Altman's Addition to Open Tomorrow; Completed Building Occupies Entire Block, with Floor Area of 1,000,000 Square Feet". The New York Times. October 4, 1914. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1985, p. 5.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1985, pp. 6–8.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1985, p. 9.

- ^ "Building Access". City University of New York. Archived from the original on September 6, 2021. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1985, p. 7.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1985, pp. 7, 9.

- ^ a b c d "Altman Store Now Covers Whole Block; Features of Madison Avenue Addition". The New York Times. January 4, 1914. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tauranac 1985, p. 71.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dunlap, David W. (January 2, 1994). "The B. Altman Building Goes Bookish". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ Tauranac 1985, pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b c d e Collins, Glenn (May 25, 1999). "In Aisle 3, Medieval Studies; Relic of Lost Era, Department Store Giant Is Reborn as a Graduate School". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Gourarie, Chava (December 28, 2016). "Vulcan pays $93M for NYPL's commercial condo at 188 Madison". The Real Deal New York. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Building Venues & Particulars". City University of New York. Archived from the original on September 20, 2021. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ "About the Library". Mina Rees Library. City University of New York. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ "About the gallery". The Center for the Humanities at the Graduate Center, CUNY. The City University of New York. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ a b "The Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library Now Open for Grab-and-Go Service". The National Herald. July 22, 2020. Archived from the original on September 6, 2021. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ "The Science, Industry, and Business Library (SIBL)" (PDF). Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ "About the Science, Industry and Business Library (SIBL)". The New York Public Library. September 16, 2016. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ a b Mendelsohn, Joyce (1998), Touring the Flatiron: Walks in Four Historic Neighborhoods, New York: New York Landmarks Conservancy, pp. 89–90, ISBN 0-964-7061-2-1, OCLC 40227695

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1985, p. 2.

- ^ Wolfe 1975, p. 207.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1985, p. 3.

- ^ Wolfe 1975, p. 196.

- ^ Wist, Ronda (1992). On Fifth Avenue : then and now. New York: Carol Pub. Group. ISBN 978-1-55972-155-4. OCLC 26852090.

- ^ "Catharine Street as Select Shopping Centre Recalled in Lord & Taylor's Coming Removal". The New York Times. November 3, 1912. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ a b c "The New Fifth Avenue". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 74, no. 1918. December 17, 1904. p. 1346 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b c d e "Altman Firm to Build a Fifth Avenue Store; New Establishment to Be Opposite Waldorf-Astoria". The New York Times. December 11, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ "In the Real Estate Field; No. 365 Fifth Avenue, Near Thirty-fifth Street, Sold – Other Dealings by Brokers and at Auction". The New York Times. July 31, 1901. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ "Gossip of the Week". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 73, no. 1868. January 2, 1904. pp. 5, 7 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Altman Going to Fifth Ave". New York Sun. December 11, 1904. p. 7. Retrieved September 9, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "B. Altman & Co. Will Move to Fifth Avenue". New York Evening World. December 10, 1904. p. 1. Retrieved September 10, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Middle Fifth Avenue's New Scale of Values; Result of Deal for New York Club Site and Adjoining Property". The New York Times. January 22, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ "Trowbridge & Livingston Architects for the Altman Store". Real Estate Record and Builders Guide. Vol. 75, no. 1923. January 21, 1905. p. 137 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "B. Altman Secures Big Loan". The New York Times. April 11, 1905. p. 17. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 10, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Hitch in Altman's Plan; Lease May Delay Building on Full Block on Fifth Avenue". The New York Times. May 18, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ "Three Dead, Score Hurt in Fifth Ave. Disaster; Workmen Drill Into Forgotten Charge of Dynamite". The New York Times. December 20, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ "Three Killed by Blast". New-York Tribune. December 20, 1905. p. 16. Retrieved September 11, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Tried to Disable Engines.; Another Plot to Stop Work in Altman Building Fails". The New York Times. December 23, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ "Nine-ton Girder Fell Among Working Gang". Brooklyn Times-Union. January 27, 1906. p. 1. Retrieved September 11, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Derrick's Fall Kills; Another of the Many Mishaps to Post & McCord's Non-Union Workers". The New York Times. January 28, 1906. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ "Altman Sells His 6th Ave. Property; Morgenthau and Greenhut Buy It". The New York Times. April 21, 1906. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ "Altman Building Opened". Brooklyn Times-Union. October 15, 1906. p. 2. Retrieved September 11, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "To Enlarge Altman Store". New-York Tribune. December 30, 1910. p. 9. Retrieved September 11, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Altman Store Complete". The New York Times. September 24, 1911. p. 79. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 11, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b "Altman & Co. Forced to Enlarge Building". New York Sun. June 8, 1913. p. 8. Retrieved September 11, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b "Altman at Last Gets Whole Block; Adds to His Store Property by a Madison Ave. Purchase at About $1,250,000". The New York Times. October 5, 1910. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ a b "Altman Secures Famous Corner". New-York Tribune. October 5, 1910. p. 1. Retrieved September 11, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Conveyances". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. Vol. 86, no. 2232. December 24, 1910. p. 1110. Retrieved April 29, 2024 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "The Real Estate Field; Investor Buys to Protect Light and Air – Plans for $1,000,000 Addition to B. Altman's Fifth Avenue Department Store Filed – New School in Lenox Hill Section to Cost $500,000". The New York Times. June 12, 1913. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ a b Tauranac 1985, p. 73.

- ^ "Benj. Altman Dies, Leaves $45,000,000; A Leader Among Merchants and the Owner of Art Objects Worth $15,000,000". The New York Times. October 8, 1913. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ "Altman in Will Had Three Aims; Wished to Continue Business in His Way, Benefit Employes and the City, Says Lawyer". The New York Times. October 16, 1913. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ "Latest Dealings in Realty Field; B. Altman & Co. Complete Purchase of Entire Block Occupied by Their Store". The New York Times. November 9, 1924. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ "B. Altman & Co, Get Control of Block". The New York Herald, New York Tribune. November 9, 1924. p. B1. Retrieved September 13, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ a b c d e f Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 534.

- ^ a b Hardy 1988, p. 14.

- ^ "Building Plans Filed; Alteration Planned by Altman's Extimated to Cost $250,000". The New York Times. June 2, 1938. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Stern, Robert A. M.; Gilmartin, Patrick; Mellins, Thomas (1987). New York 1930: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Two World Wars. New York: Rizzoli. p. 308. ISBN 978-0-8478-3096-1. OCLC 13860977.

- ^ "Altman's to Spend $1,000,000 on Store; Fifth Ave. Establishment Plans Expansion as Contribution to Business Revival". The New York Times. May 16, 1938. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "Altman Turns 3d Floor Into 'Fifth Avenue Walk'". New York Herald Tribune. January 13, 1940. p. 31. Retrieved September 11, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "B. Altman Assures Customers on Site". The New York Times. December 15, 1970. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Shepard, Joan (March 15, 1985). "Landmark Designation for B. Altman". New York Daily News. p. 1272. Retrieved December 3, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Barmash, Isadore (November 20, 1984). "A Smaller Altman's Store Due". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ Teltsch, Kathleen (May 13, 1984). "Charity Law May Force Sale of Altman's Store". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ Barmash, Isadore (May 21, 1985). "B. Altman Conversion Advancing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ Rangel, Jesus (March 13, 1985). "Upper West Side History in Proposed District". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c Dunlap, David W. (November 17, 1991). "Commercial Property: B. Altman's; A Metamorphosis For 880,000 Sq. Ft". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ "Company News; Hooker Gets Rest of Altman". The New York Times. November 7, 1987. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Lyall, Sarah (November 24, 1987). "Major Renovation Planned at Midtown Altman's". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ "Altman's new owner to build on upward". The Journal News. November 27, 1987. p. 51. Retrieved September 12, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Hardy 1988, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, pp. 534–535.

- ^ a b Donovan, Roxanne (January 4, 1990). "Future looms large for Altman building". New York Daily News. p. 55. Retrieved September 12, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Murphy, Jim (March 1988). "Addition Proposed For New York City Landmark" (PDF). Progressive Architecture. Vol. 69. pp. 37, 40.

- ^ a b c Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 535.

- ^ Schiro, Anne-Marie (November 17, 1988). "Fifes and Drums Hail a New Look at Altman's". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Barmash, Isadore (August 10, 1989). "Bonwit's Owner Files for Bankruptcy". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ Barmash, Isadore (November 18, 1989). "No Bidder To Rescue B. Altman". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ "Headliners; In Its Final Days, Altman's Has Crowds at Last". The New York Times. November 26, 1989. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ Lebow, Joan (November 27, 1989). "Altman Store's Landmark Status Is Set In Stone, but Usage Is Another Story". Wall Street Journal. p. 1. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 398115114.

- ^ "Design center set for B. Altman site". New York Daily News. August 22, 1991. p. 141. Retrieved September 12, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Details" (PDF). Architecture. Vol. 80. September 1991. p. 21.

- ^ Finder, Alan (November 22, 1991). "Public Library Will Issue Bonds To Buy Part of Altman Building". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Hogrefe, Jeffrey (March 30, 1998). "Alfred Taubman Plans for 'Art Mall' on Top of Sotheby's Fortress". Observer. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Fulman, Ricki (April 6, 1990). "Penney may turn up in B. Altman place". New York Daily News. p. 164. Retrieved September 12, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (February 28, 1993). "Postings; Library Buys Piece Of Altman's". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Lambert, Bruce (August 6, 1995). "Neighborhood Report: Midtown; Domino Real-estate Deal Cleared". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (April 24, 1996). "Grandeur and Modernity in New Library". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Arenson, Karen W. (August 20, 1999). "CUNY Graduate Center Puts Off Classes in Its Unfinished Building". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ "Crystal Report – Financial Year 2011" (PDF). City University of New York. City University of New York. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ Arenson, Karen W. (April 5, 2000). "Graduate Center Adds Life to a CUNY Institution". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ Pogrebin, Robin (February 15, 2012). "Ambitions Rekindled at Public Library". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Smith, Jennifer (November 16, 2016). "New York Public Library Approves $200 Million Makeover of Mid-Manhattan Branch". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ Passy, Charles (June 1, 2018). "Pop-Culture Museum Eyes a Second Home". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Weaver, Shaye (June 6, 2018). "Seattle's Museum of Pop Culture, featuring 'Star Trek,' Marvel and more exhibits, eyes Manhattan location". amNewYork. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ "About the Business Center at Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library (SNFL)". The New York Public Library. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ "Best & Co. in Fifth Avenue.; Concern Will Retain Its 23d Street Store and Open Another". The New York Times. September 16, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ The Pacific Printer: The Leading Trade Journal in the West for the Printing and Allied Interests, Vol. 21–22. 1919. p. 220. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- ^ White, Willensky & Leadon 2010, p. 268.

- ^ "5th Ave. Building Sold; Library Buys Property at 40th St. for Investment". The New York Times. October 20, 1961. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ White, Willensky & Leadon 2010, p. 338.

- ^ Medd, James (April 24, 2018). "'The Marvelous Mrs Maisel': where were seasons 1, 2 and 3 filmed?". CN Traveller. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on March 12, 2020. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

Sources

[edit]- B. Altman and Company Building (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. March 12, 1985.

- Hardy, Hugh (January 1988). "Altman's Midtown Center" (PDF). Oculus. Vol. 50, no. 5. pp. 14–15.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Fishman, David; Tilove, Jacob (2006). New York 2000: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Bicentennial and the Millennium. New York: Monacelli Press. ISBN 978-1-58093-177-9. OCLC 70267065. OL 22741487M.

- Tauranac, John (1985). Elegant New York. New York: Abbeville Press. ISBN 978-0-89659-458-6. OCLC 12314472.

- White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- Wolfe, Gerald R. (1975). New York, a Guide to the Metropolis: Walking Tours of Architecture and History. Washington Mews books. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-9163-9.