2018 Russian presidential election

The article's lead section may need to be rewritten. (January 2024) |

| |||||||||||||||||

| Opinion polls | |||||||||||||||||

| Registered | 109,008,428 | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 67.50% ( | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

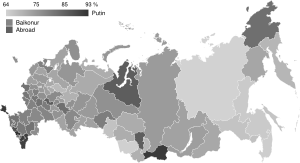

Results by federal subject | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Presidential elections were held in Russia on 18 March 2018. Incumbent president Vladimir Putin was eligible to run. He declared his intent to do so on 6 December 2017 and was expected to win. This came following several months of speculation throughout the second half of 2017 as Putin made evasive comments, including that he had still not decided whether he would like to "step down" from the post of president, that he would "think about running", and that he "hadn't yet decided whether to run for another term". Different sources predicted that he would run as an independent to capitalize more support from the population, and although he could also have been nominated by the United Russia party as in 2012, Putin chose to run as an independent. Among registered voters in Russia, 67.5% voted in the election

There were allegations of widespread electoral fraud, including ballot box stuffing, forced voting, and threats against election observers. A video widely shared online showed people stuffing papers into ballot boxes. In addition, critics of Putin were barred from running.[1]

Putin won re-election for his second consecutive (fourth overall) term in office with 77% of the vote. Vladimir Zhirinovsky from the Liberal Democratic Party was the perennial candidate, having unsuccessfully run in five previous presidential elections. Other candidates included Pavel Grudinin (Communist Party), Sergey Baburin (Russian All-People's Union), Ksenia Sobchak (Civic Initiative), Maxim Suraykin (Communists of Russia), Boris Titov (Party of Growth) and Grigory Yavlinsky (Yabloko). Anti-corruption activist Alexei Navalny announced his intent to run in December 2016 but was barred from doing so due to a prior criminal conviction, which was widely seen as politically motivated,[2][3][4] for corruption. Consequently, Navalny called for a boycott of the election. He had previously organized several public rallies against corruption among members of Putin's government.

Background

[edit]

The President of Russia is directly elected for a term of six years, since being extended from four years in 2008 during Dmitry Medvedev's administration.[5] According to Article 81 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation, a candidate for president must be at least 35 years old, hold no dual nationality, have permanently resided in Russia for the past 10 years, and cannot serve more than two terms consecutively.[6] Parties with representation in the State Duma can nominate a candidate to run for office while candidates from officially registered parties that are not in parliament have to collect at least 100,000 signatures. Independent candidates have to collect at least 300,000 signatures with no more than 7,500 from each federal subject of Russia[citation needed] and also from action groups made up of at least 500 people.[7] The nomination process took place during Russia's winter holiday period, and 31 January 2018 was the last day for submitting signatures in support of contested access candidates.

Change of date

[edit]On 3 March 2017, senators Andrey Klishas and Anatoly Shirokov submitted to the State Duma draft amendments to the electoral legislation. One of the amendments involves the transfer of elections from the second to the third Sunday in March, i.e. from 11 to 18 March 2018.[8] According to article 5, paragraph 7 of Russian Federal law No. 19-FZ, "If the Sunday on which presidential elections are to be held coincides with the day preceding a public holiday, or this Sunday falls on the week including a public holiday or this Sunday is declared to be a working day, elections are appointed on the following Sunday". The second week of March includes International Women's Day (8 March), which is an official holiday in Russia.[9] The bill passed through the State Duma and Federation Council without delay in May 2017 and was signed into law by Vladimir Putin on 1 June 2017.[10][11] On 15 December, the upper house of the Federal Assembly, the Federation Council, officially confirmed that 18 March 2018 will be the date of the election, officially beginning the process of campaigning and registration for candidates.[citation needed] This date is significant in the country as it is the fourth anniversary of Russian annexation of Crimea.[12]

A total of 97,000 polling stations were open across the country from 08:00 until 20:00 local time.[13]

Nomination of candidates

[edit]Free access

[edit]Political parties represented in the State Duma or the legislative bodies of not less than one-third of the federal subjects could nominate a candidate without collecting signatures. The following parties could nominate candidates without collecting signatures: Civic Platform, the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia, A Just Russia, Rodina and United Russia.

On 1 July 2017, Chairman of Rodina Aleksey Zhuravlyov announced that his party would only support incumbent president Vladimir Putin in the election.[14] On 11 December, the leader of Civic Platform Rifat Shaykhutdinov also said that his party would support Putin.[15] On 24 December, the leader of A Just Russia Sergey Mironov stated that his party would not put forward a candidate. Senior party member Mikhail Yemelyanov confirmed that A Just Russia would support Putin's candidacy.[16]

Contested access

[edit]Individuals belonging to a party without any seats in the State Duma had to collect 105,000 signatures to become candidates, while those running as independents had to collect 315,000 and also to form a group of activists made up of at least 500 people.[17] Multiple political commentators, including former presidential hopeful Irina Khakamada, talked about the difficulty of gathering signatures without the support of a political party, a hurdle which cast doubt on many of the claims of the large number of people who said that they would run for president as independents.[18] However, according to CEC Chairwoman Ella Pamfilova, the conditions for contested-access candidates were easier than ever because such potential candidates no longer had to collect 1,000,000 signatures. Pamfilova incorrectly predicted that there could be even more candidates in this election than there were in 2000, when 11 candidates contested the presidency (the largest number of candidates in the history of presidential elections in Russia).[19]

Primaries

[edit]Party of Growth

[edit]In July 2017, the Party of Growth announced that it would hold primaries to nominate a presidential candidate. Four candidates participated in the primaries: Oksana Dmitriyeva, Dmitry Potapenko, Dmitry Marinichev and Alexander Huruji. Voting was conducted via the Internet from August to November 2017.[20]

On 10 August 2017, the party's press secretary told the media that the results of the primaries will be taken into account at the party congress which will be held to decide the candidate for Party of Growth. However, the winner of the primaries would not guarantee themselves the right to run on behalf of the party.[21]

On 26 November, it was announced that the party would nominate Boris Titov, who was not involved in the primaries. According to a person from the party leadership, none of the proposed candidates could obtain sufficient support.[22]

Left Front

[edit]On 2 November 2017, the Left Front headed by Sergei Udaltsov started online primaries for the nomination of a single left-wing candidate. Primaries were held in two rounds, the first round took place from 2 to 23 November, and the second round – from 24 to 30 November.

The first round included 77 candidates, among whom were representatives of various left-wing political parties and organizations, including Pavel Grudinin, Yury Boldyrev, Gennady Zyuganov, Sergey Mironov (who later supported Vladimir Putin), Sergey Glazyev, Zakhar Prilepin, Viktor Anpilov, Valery Zorkin, Zhores Alferov, Sergey Baburin (who later was nominated as a candidate from the party Russian All-People's Union), Natalia Lisitsyna (who was later nominated as a candidate from the Russian United Labour Front), Maxim Suraykin (who was nominated as a candidate from the Communists of Russia) and others.[23]

Boldyrev and Grudinin made it through to the second round, which was won by Grudinin, who garnered 4,086 votes (58.4%).[24]

At the end of December 2017, Grudinin was officially nominated as the candidate from the Communist Party.

Third Force

[edit]The bloc Third Force held primaries among candidates from ten non-parliamentary parties to nominate presidential candidates. According to the organizers, the primaries would determine four presidential candidates representing different views.[25][26]

The official presentation of the candidates was held on 30 October 2017. The candidates included: Andrei Bogdanov, Andrey Getmanov, Olga Onishchenko, Stanislav Polishchuk, Sirazhdin Ramazanov, Ildar Rezyapov, Vyacheslav Smirnov, Irina Volynets and Alexey Zolotukhin.[27]

However, the block failed to identify a clear winner, then all candidates, except for Olga Onishchenko declared that they would participate in the elections. Later, however, all of the candidates refused to participate.[28][29][30]

Candidates

[edit]

These candidates were officially registered by the CEC. Candidates are listed in the order they appear on the ballot paper (alphabetical order in Russian).[31]

| Candidate name, age, political party |

Political offices | Campaign | Details | Registration date | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sergey Baburin (59) Russian All-People's Union |

|

People's Deputy of Russia (1990–1993) Deputy of the State Duma (1994–2000, 2003–2007) Leader of the Russian All-People's Union (2011–present) |

(Campaign • Website) |

On 22 December 2017, the Russian All-People's Union nominated Baburin as its presidential candidate.[32] On 24 December, Baburin filed registration documents with the CEC.[33] The CEC rejected Baburin's bid on 25 December because it identified violations in the information provided regarding 18 of his party's 48 representatives.[34] Baburin resubmitted the documents and they were approved by the CEC.[35] | 7 February 2018[36] | |

| Pavel Grudinin (57) Communist Party |

|

Deputy of the Moscow Oblast Duma (1997–2011) |

(Campaign • Website) |

Although Communist Party leader and perennial candidate Gennady Zyuganov said all leftist forces supported his nomination and he would participate in the elections on behalf of the party, the Zhigulevsk branch of the party voted to support the candidacy of Grudinin, who also won the primaries of Left Front, a coalition of left-wing parties with no representation in the State Duma. Grudinin did not deny his nomination from the Communist Party.[37] On 21 December 2017 it was reported that Zyuganov proposed to nominate Grudinin.[38] Initially the Communist Party and the National Patriotic Forces of Russia (NPFR) planned to nominate a single candidate: Grudinin (supported by the Communists) or Yury Boldyrev (supported by the NPFR). Boldyrev also participated in the primaries of Left Front in which he lost in the second round to Grudinin.[39] According to the Deputy Alexander Yushchenko, Zyuganov was still among the candidates for the nomination. He named the other candidates as Yury Afonin, Sergey Levchenko and Leonid Kalashnikov. On 22 December Zyuganov, Levchenko and Kalashnikov withdrew their bids, and Zyuganov rejected the candidacies of Afonin and Boldyrev, leaving Grudinin as the sole candidate.[40] Grudinin was officially nominated at the party congress on 23 December.[41] Zyuganov is the head of Grudinin's presidential campaign.[42] Grudinin filed registration documents with the CEC on 28 December[43] and 9 January 2018.[44] | 12 January 2018[45] | |

| Vladimir Zhirinovsky (71) Liberal Democratic Party |

|

Deputy of the State Duma (1993–2022) Leader of the Liberal Democratic Party (1991–2022) |

(Campaign) |

In June 2015, Zhirinovsky said he plans to participate in presidential elections, but in July of the same year, the politician said that the Liberal Democratic Party, perhaps "will pick a more efficient person."[46][47] Already in March 2016, he announced the names of those who were likely to be nominated as a candidate from the Liberal Democratic Party. This included Deputy Chairman of the State Duma Igor Lebedev or deputies Mikhail Degtyarev, Yaroslav Nilov and Alexei Didenko.[48] On 28 October 2016, the LDPR's official website released a statement announcing that the party will nominate Zhirinovsky as their presidential candidate.[49][50] This is the fifth time that he is running for president since the breakup of the Soviet Union (and sixth overall). Zhirinovsky was officially nominated by his party at its 31st congress on 20 December 2017.[51] He submitted to the CEC some of the documents required for registration the next day,[52] and the rest of them on 27 December.[53] At 71, Zhirinovsky is the oldest person to run for president in Russia.[54] | 29 December 2017[55] | |

| Vladimir Putin (65) Independent |

|

President of Russia (2000–2008 and 2012–present) Prime Minister of Russia (1999–2000 and 2008–2012) Leader of United Russia (2008–2012) Director of the Federal Security Service (1998–1999) |

(Campaign • Website) |

On 6 December 2017, Putin announced that he would run for a second consecutive term.[56] Putin announced that he would run as an independent at his annual press conference on 14 December.[57] Putin's action group officially put forward his nomination in Moscow on 26 December.[58] Putin filed registration documents with the CEC the next day.[59] The CEC approved his documents on 28 December.[60] On 29 January, Putin handed over the signatures to the CEC. By 2 February, they had been verified – only 232 signatures were deemed invalid.[61] | 6 February 2018[62] | |

| Ksenia Sobchak (36) Civic Initiative |

|

None | (Campaign • Website) |

TV anchor, opposition activist, and journalist Ksenia Sobchak announced that she would run for president in October 2017.[63] Sobchak is the first female candidate in 14 years and the youngest candidate to run since 2004.[64][65] Sobchak was nominated by Civic Initiative at the party's congress on 23 December and became a member of the party.[66] Sobchak filed registration documents with the CEC on 25 December.[67] Her documents were approved by the CEC on 26 December.[68] | 8 February 2018[69] | |

| Maxim Suraykin (39) Communists of Russia |

|

Chairman of the Central Committee of the Communists of Russia (2012–present) |

(Campaign) |

The Central Committee of the Communists of Russia party announced the nomination of its chairman Maxim Suraykin as its candidate for the election in February 2017. Suraykin stated that he aims to at least come in second place, and defeat Zyuganov's larger Communist Party of the Russian Federation.[70] CR nominated Suraykin at the party congress in Moscow on 24 December.[71] He filed registration documents with the CEC on the same day.[72] Suraykin's documents were approved by the CEC on 25 December.[73] | 8 February 2018[74] | |

| Boris Titov (57) Party of Growth |

|

Leader of the Party of Growth (2016–present) Presidential Commissioner for Entrepreneurs' Rights |

(Campaign • Website) |

The leader of the Party of Growth, Presidential Commissioner for Entrepreneurs' Rights Boris Titov declared that he would participate in the presidential election on 26 November 2017. Initially, the party conducted primaries in which Titov did not participate, however, according to the party leadership, none of the candidates received sufficient support.[75] Titov was officially nominated by his party on 21 December.[76] He submitted to the CEC the documents required for registration the next day.[77] Titov's documents were approved by the CEC on 25 December.[78] | 7 February 2018[79] | |

| Grigory Yavlinsky (65) Yabloko |

|

Chairman of Yabloko (1993–2008) Deputy of the State Duma (1993–2003) Deputy of the Legislative Assembly of St. Petersburg (2011–2016) |

(Campaign • Website) |

Suggestions that Yavlinsky would run for president in 2018 were first made in 2013,[80] and he was announced as the candidate from the Yabloko party at a convention in February 2016, having been previously the party's candidate for the presidency in 1996 and 2000.[citation needed] In the weeks following the announcement he began campaigning for the election early by traveling to multiple cities across the country.[81] Yabloko nominated Yavlinsky at its party congress on 22 December.[82] He submitted to the CEC the documents required for registration the next day.[83] Yavlinsky's documents were approved by the CEC on 25 December.[84] | 7 February 2018[85] | |

Campaigning

[edit]Sergey Baburin

[edit]

Sergey Baburin was nominated at the party congress on 22 December 2017.[32] On 24 December, Baburin filed registration documents with the CEC,[33] but the documents were rejected 25 December because the CEC identified violations in the information provided regarding 18 of his party's 48 representatives.[34] On 29 December, Baburin resubmitted the documents and they were approved by the CEC.[35]

Russian All-People's Union started to collect signatures in support of Baburin on 9 January 2018. Signatures were collected in 56 federal subjects.[86][87] On 30 January 2018, Sergey Baburin handed over the signatures to the CEC. When testing revealed only 3.28% of invalid signatures, Sergey Baburin was admitted to the election.[88][89]

Pavel Grudinin

[edit]

At the end of November 2017, Pavel Grudinin won the primaries of Left Front, a coalition of left-wing parties with no representation in the State Duma. Some branch of the Communist Party voted to support the candidacy of Grudinin and did not deny his nomination from the Communist Party.[37] Despite the fact that in early November the First Secretary of the Communist party, Gennady Zyuganov, said that his nomination is supported by all left-wing organizations, which the media felt was the official statement from Zyuganov to participate in the election, Zyuganov later denied this, saying that the official decision will be made at the party Congress in December. On 21 December, it was reported that Zyuganov proposed to nominate Grudinin.[90]

Initially, the Communist Party and the National Patriotic Forces of Russia (NPFR) planned to nominate a single candidate: Grudinin, supported by the Communists, or Yury Boldyrev, supported by the NPFR. Boldyrev also participated in the primaries of the Left Front, where he lost in the second round to Grudinin.[91] According to Deputy Alexander Yushchenko, Gennady Zyuganov was still among the candidates for the nomination. He named the other candidates as Yury Afonin, Sergey Levchenko, and Leonid Kalashnikov. On 22 December, Zyuganov, Levchenko, and Kalashnikov withdrew their bids, and Zyuganov rejected the candidacies of Afonin and Boldyrev, leaving Grudinin as the sole candidate.[40] Grudinin was officially selected as the presidential candidate from the Communist Party at its congress on 23 December.[92]

Alexei Navalny

[edit]

Russian opposition figure and anti-corruption blogger Alexei Navalny started his presidential campaign on 13 December 2016.[93] In early 2017, he traveled to different cities across Russia to open campaign offices and meet with his supporters, despite his involvement in legal cases that might have barred him from running. As noted in an article by Newsweek and by the former Russian presidential administration adviser Gleb Pavlovsky,[94] the American-style campaign by Navalny was unprecedented in modern Russia as most candidates do not start campaigning until a few months before the election. The primary focus of Navalny's campaign was combating corruption within the current government under Vladimir Putin and Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev.[95] On 2 March, Navalny published a documentary on YouTube titled He Is Not Dimon To You, detailing the corrupt dealings of Prime Minister Medvedev.[96][97] He then called for mass rallies to be held on 26 March to bring attention to this after the government did not respond to the documentary, which only about 150.000 people attended across Russia. 2017–2018 Russian protests[98][99] 26 March rally was the largest protest held in Russia since the protests in 2011.[100] Navalny called for another protest to be held on Russia Day, which is 12 June.[101]

On his website, Navalny listed the main principles of his presidential program: combating government corruption, improving infrastructure and living standards in Russia, decentralizing power from Moscow, developing the economy instead of remaining in isolation from the West, and reforming the judicial system.[102] His more specific economic proposals included instituting a minimum wage,[103] lowering prices of apartments and reducing bureaucracy of home construction, making healthcare and education free, lowering taxes for many citizens, taxing the gains from privatization, decentralization of financial management and increase in local governance, increasing transparency in state-owned firms, implementing work visas for Central Asian migrants coming into the country for work, and increasing economic cooperation with western European states.[104]

In April 2017, it was reported that Navalny's campaign staff had collected more than 300,000 pledged signatures from people across 40 regions of Russia electronically.[105] More than 75,000 people signed up to volunteer for his campaign and nearly $700,000 has been donated.[106] However, his eligibility was put into question by his five-year suspended sentence for embezzlement of timber from the company Kirovles, when Navalny was working as an aide to Governor Nikita Belykh of the Kirov Oblast. The Russian Supreme Court overturned his sentence in November 2016 after the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) determined that Navalny's rights were violated, and sent the case back to a district court in the city of Kirov for review.[107] In February 2017, the district court upheld Navalny's suspended sentence.[108] The Constitution of Russia does not allow convicted criminals to run for office. Navalny promised to appeal the result to the ECHR, and said he would continue campaigning,[109] while in early May the deputy head of the Russian Central Election Commission (CEC) commented that he would not be allowed to run unless the sentence is overturned.[110] In August, the head of the CEC, Ella Pamfilova, reinforced this sentiment, saying that it would "take a miracle" for Navalny to be granted permission to run.[111] She cited two scenarios in which Navalny could run: if his conviction was overturned, or if the federal election law was rapidly changed to allow those with criminal convictions to run. Pamfilova added that the probability of either scenario was "extremely low". Pamfilova later commented that Navalny could legally run for president by "some time in 2028", i.e., ten years after his sentence expires.[112] The Memorial Human Rights Center recognized Navalny as a political prisoner.[113]

Members of the Navalny campaign were harassed and detained by the police, including his chief of staff Leonid Volkov, who was sentenced to thirty days in jail in early December for organizing an unauthorized rally (requests for rallies in city centers are often denied in Russia[114]) in Nizhny Novgorod.[115][116]

Navalny published his election manifesto on 13 December 2017, two days before the official start of campaigning.[117]

He officially submitted his documents for registration as a candidate on 24 December 2017 and was rejected by the CEC the following day due to his conviction. Later that same day, 25 December, Navalny called on his supporters to boycott the election in response. Mass street protests were planned for 28 January 2018.[118]

Vladimir Putin

[edit]

Vladimir Putin announced his run on 6 December 2017, during his speech at the GAZ automobile plant.[119] A Just Russia,[120] Civic Platform,[15] The Greens,[121] Great Fatherland Party,[122] Labor Party,[123] Party of Pensioners,[124] Patriots of Russia,[125] Rodina,[126] and United Russia[127] endorsed his presidential bid.

Ksenia Sobchak

[edit]

Rumors about the nomination of Ksenia Sobchak in the 2018 election appeared a month before she officially announced that she would run for president.[128]

Sobchak officially announced that she would run for president on 19 October 2017, in a YouTube video. In the video, Sobchak said she is the candidate "against all", because since the 2004 election, the "against all" option (or "none of the above" as it is more commonly known in English-speaking countries) has been excluded from the ballot, and Sobchak wants to give people the opportunity to again vote "against all". At the same time, Sobchak said she will withdraw her candidacy if Alexey Navalny is registered as a candidate by the Central Election Commission.[129]

Originally Sobchak put herself forward as an independent candidate. In this case, she would have had to collect at least 300,000 signatures to be admitted to the election. Soon after, however, Sobchak's campaign team said that would be nominated by a political party, namely the People's Freedom Party or Civic Initiative.[130]

On 15 November 2017, it was announced that Sobchak would be nominated by Civic Initiative at its congress in December.[131]

On 23 December 2017, at the Civic Initiative's congress, Sobchak was officially nominated for president. On the same day, she joined the party.[132] Sobchak's team began gathering signatures in support of her candidacy on 27 December, soon after her registration documents were approved by the CEC.[133]

Maxim Suraykin

[edit]

In December 2017, it became known that the party Communists of Russia nominated Maxim Suraykin as presidential candidate.[134]

On 28 May 2017, the Plenum of the Central Committee of the Communists of Russia decided on the nomination of Maxim Suraykin as a presidential candidate.

In November 2017, Maxim Suraykin was one of the candidates proposed by the Left Front as a single candidate from the left opposition. The results of the voting on the website of the Left Front Suraikin won 59 votes.[135]

On 24 December Maxim Suraykin was officially nominated at the Communists Russia National Convention. On the same day he also submitted to the Central Election Commission.[136]

Boris Titov

[edit]

Initially the Party of Growth conducted primaries which were attended by four candidates: Oksana Dmitriyeva, Dmitry Potapenko, Dmitry Marinichev and Alexander Khurudzhi.[137] Boris Titov did not participate in the primaries. However, at the meeting of the federal council of the party, it was decided to nominate Titov. According to a person from the party leadership, none of the proposed candidates could obtain sufficient support.[138]

According to Titov, the main task of participation in the election is to promote the party's Growth Strategy economic program, which was prepared by the Stolypin Club and presented to President Vladimir Putin in May 2017. During the campaign, Titov and his team intend to travel around the country to promote the program.[139]

Titov was officially nominated by his party on 21 December.[76] He submitted to the CEC the documents required for registration the next day.[77] Titov's documents were approved by the CEC on 25 December, which meant that he could begin collecting signatures.[140] A party spokesman commented that the collection signatures in support of Titov will begin in early January 2018.[141]

Grigory Yavlinsky

[edit]

Economist Grigory Yavlinsky announced his presidential bid in February 2016 as the candidate for the liberal party Yabloko, though suggestions that he would run were first voiced in 2013 after he was barred from taking part in the 2012 election.[80] His policies mainly focus on improving the economic situation through governance reforms and stopping involvement in conflicts.[142] He was nominated by the party leader, Emilia Slabunova, who stressed the need to unite all "democratic forces" behind one candidate and noted his political experience and also received an endorsement from opposition politician Vladimir Ryzhkov. Yavlinsky had previously run in the 1996 and 2000 presidential elections, getting 7.4% of the vote in the former.[citation needed] He spoke at a party forum announcing the start of the campaign in February 2017. One proposal he made was to give out several acres of free land to families so they could build home there and develop it, which he said would house 15 million families,[143] and to turn the Russian Armed Forces into a fully professional military by abolishing conscription.[144]

In March 2017, Yavlinsky stated that he would be visiting several major cities in fifteen different regions across the country to raise support. He used Alexei Navalny's recent tour of different cities as an example, refusing to use the traditional model of campaigning a few months before the election. Since he is unable to visit more locations, Slabunova, the leader of Yabloko, and Nikolai Rybakov, his chief of staff, will go to other cities to campaign as well.[81]

On 1 November 2017, Yabloko launched the official website of Yavlinsky's campaign.[145]

Vladimir Zhirinovsky

[edit]

Vladimir Zhirinovsky announced his participation in the presidential elections on 28 October 2016 as the candidate for the Liberal Democratic Party. In the event of his election, Zhirinovsky promised to amend the Constitution of Russia and to radically change the policies of the country. In particular, Zhirinovsky promised to abolish the federal structure of Russia and to return to the Governorates, rename the post of "President of Russia" to the "Supreme Ruler of Russia" and to restore Russia's borders to the borders of the USSR as of 1985.[49]

In March 2017, Zhirinovsky promised to declare a general amnesty if elected president.[146]

Debates

[edit]On 14 February 2018, the CEC set the schedule for the distribution of airtime for presidential candidates.[147] Debates took place on five federal TV channels: Russia 1, Russia 24, Channel One, TV Center and PTR, as well as on three radio stations: Radio Rossii, Radio Mayak and Vesti FM. As in previous election campaigns, incumbent President Vladimir Putin refused to participate in the debates.[148][149][150][151]

Debates occurred from 26 February to 15 March.[152] Vladimir Zhirinovsky was the only candidate to attend the first debate, with the other three candidates sending representatives.[153] The second debate, which didn not involve any candidate-to-candidate discussion, was attended by six candidates and Boris Titov's representative.[154]

| 2018 Russian presidential election debates | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Organizer | Moderator | P Candidate was present R Representative attended A Both candidate and representative were absent | Notes | |||||||

| Baburin | Grudinin | Zhirinovsky | Putin | Sobchak | Suraykin | Titov | Yavlinsky | ||||

| 26 February 13:10 MT |

Radio Rossii | A | R | P | A | R | A | R | A | [155] | |

| 28 February 09:00 MT |

Channel One | Anatoly Kuzichev | P | P | P | A | P | P | R | P | |

| 28 February 23:15 MT |

Russia 1 | Vladimir Solovyov | P | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | |

| 1 March | Russia 24 | P | R | P | A | P | P | R | P | [156] | |

Opinion polls

[edit]Opinion polls published in the months preceding the election consistently showed Putin with an overwhelming lead over his competitors.

Exit polls

[edit]| Poll source |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Invalid ballots |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Putin | Grudinin | Zhirinovsky | Sobchak | Yavlinsky | Titov | Suraykin | Baburin | ||

| FOM | 76.3% | 11.9% | 6% | 2% | 1% | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.6% | |

| WCIOM | 73.9% | 11.2% | 6.7% | 2.5% | 1.6% | 1.1% | 0.8% | 1.0% | 1.2% |

Elections in Crimea

[edit]The European Union had already announced in advance that it would not recognize the results of the Russian presidential election in the annexed Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea. EU foreign affairs chief Federica Mogherini said the EU would follow through with its non-recognition policy and called on Russia to respect the rights of Ukrainian citizens.[157] President of Austria Alexander Van der Bellen also warned that Moscow could not hold a legal election on the Crimean peninsula because the annexation of Crimea was illegal.[158]

The EU and the OSCE had made it clear that they would not send any election observers to Crimea, as neither organizations see it as a legitimate part of Russia. Russian authorities then invited a number of friendly and sometimes marginalized foreign politicians to give the elections in Crimea the appearance of international acceptance. Leonid Slutsky, chairman of the parliament's foreign affairs committee, named Andreas Maurer[159] from the Left, Hendrik Weber from an organization called People's Diplomacy Norway, Pedro Agramunt and Thierry Mariani. Russia commissioned Slutsky's own organization, the Russian Peace Foundation, and the Polish association European Council on Democracy and Human Rights, which in the past had brought election observers from right-wing populist and right-wing extremist circles to Crimea, to organize their trips.[160][161][162]

Results

[edit]The final results of the elections were approved by the CEC on 23 March 2018.[163]

| Candidate | Party | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vladimir Putin | Independent | 56,430,712 | 77.53 | |

| Pavel Grudinin | Communist Party | 8,659,206 | 11.90 | |

| Vladimir Zhirinovsky | Liberal Democratic Party | 4,154,985 | 5.71 | |

| Ksenia Sobchak | Civic Initiative | 1,238,031 | 1.70 | |

| Grigory Yavlinsky | Yabloko | 769,644 | 1.06 | |

| Boris Titov | Party of Growth | 556,801 | 0.76 | |

| Maxim Suraykin | Communists of Russia | 499,342 | 0.69 | |

| Sergey Baburin | Russian All-People's Union | 479,013 | 0.66 | |

| Total | 72,787,734 | 100.00 | ||

| Valid votes | 72,787,734 | 98.92 | ||

| Invalid/blank votes | 791,258 | 1.08 | ||

| Total votes | 73,578,992 | 100.00 | ||

| Registered voters/turnout | 109,008,428 | 67.50 | ||

| Source: CEC | ||||

By federal subject

[edit]| Region | Putin | Grudinin | Zhirinovsky | Sobchak | Yavlinsky | Titov | Suraykin | Baburin | Invalid votes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | |

| 203,095 | 81.17 | 28,711 | 11.48 | 8,923 | 3.57 | 2,060 | 0.82 | 1,197 | 0.48 | 1,088 | 0.43 | 1,317 | 0.53 | 1,165 | 0.47 | 2,647 | 0.47 | |

| 770,278 | 64.66 | 281,978 | 23.67 | 84,785 | 7.12 | 11,778 | 0.99 | 7,259 | 0.61 | 5,532 | 0.46 | 7,885 | 0.66 | 7,581 | 0.64 | 14,203 | 0.64 | |

| 72,674 | 70.62 | 21,259 | 20.66 | 5,376 | 5.22 | 929 | 0.90 | 483 | 0.47 | 340 | 0.33 | 431 | 0.42 | 446 | 0.43 | 974 | 0.43 | |

| 264,493 | 67.04 | 73,485 | 18.62 | 37,909 | 9.61 | 4,428 | 1.12 | 2,466 | 0.63 | 2,080 | 0.53 | 1,951 | 0.49 | 2,358 | 0.6 | 5,383 | 0.60 | |

| 407,190 | 75.27 | 51,868 | 9.59 | 46,925 | 8.67 | 10,588 | 1.96 | 6,239 | 1.15 | 4,982 | 0.92 | 3,842 | 0.71 | 4,448 | 0.82 | 4,880 | 0.82 | |

| 342,195 | 76.95 | 64,047 | 14.40 | 19,339 | 4.35 | 5,060 | 1.14 | 2,504 | 0.56 | 2,233 | 0.50 | 2,823 | 0.63 | 2,185 | 0.49 | 4,340 | 0.49 | |

| 7,568 | 78.35 | 1,026 | 10.60 | 628 | 6.50 | 130 | 1.35 | 70 | 0.72 | 50 | 0.52 | 51 | 0.53 | 32 | 0.33 | 104 | 0.33 | |

| 1,784,626 | 77.69 | 277,797 | 12.09 | 115,635 | 5.03 | 28,983 | 1.26 | 19,390 | 0.84 | 15,891 | 0.69 | 20,429 | 0.89 | 15,845 | 0.69 | 18,506 | 0.69 | |

| 711,392 | 79.71 | 93,102 | 10.43 | 49,685 | 5.57 | 8,474 | 0.95 | 4,445 | 0.50 | 4,835 | 0.54 | 6,534 | 0.73 | 5,218 | 0.58 | 8,749 | 0.58 | |

| 636,087 | 81.60 | 68,375 | 8.77 | 43,940 | 5.64 | 7,463 | 0.96 | 3,524 | 0.45 | 4,175 | 0.54 | 4,265 | 0.55 | 4,472 | 0.57 | 7,177 | 0.57 | |

| 334,381 | 73.72 | 66,876 | 14.74 | 29,087 | 6.41 | 7,618 | 1.68 | 3,631 | 0.80 | 1,882 | 0.40 | 2,471 | 0.54 | 1,746 | 0.38 | 5,980 | 0.38 | |

| 593,806 | 91.44 | 30,012 | 4.62 | 1,631 | 0.25 | 3,531 | 0.54 | 4,848 | 0.75 | 3,285 | 0.51 | 2,093 | 0.32 | 7,679 | 1.18 | 2,497 | 1.18 | |

| 1,275,822 | 73.00 | 227,134 | 12.99 | 121,670 | 6.96 | 31,326 | 1.79 | 21,573 | 1.23 | 16,181 | 0.93 | 13,243 | 0.76 | 13,468 | 0.77 | 27,234 | 0.77 | |

| 22,709 | 82.31 | 1,616 | 5.86 | 2,018 | 7.31 | 358 | 1.30 | 160 | 0.58 | 180 | 0.65 | 142 | 0.51 | 115 | 0.42 | 293 | 0.42 | |

| 539,036 | 77.29 | 85,780 | 12.30 | 36,890 | 5.29 | 9,500 | 1.36 | 3,878 | 0.56 | 3,950 | 0.57 | 4,907 | 0.70 | 3,710 | 0.53 | 9,763 | 0.53 | |

| 994,569 | 92.15 | 23,773 | 2.20 | 19,506 | 1.81 | 17,764 | 1.65 | 5,138 | 0.48 | 2,785 | 0.26 | 2,267 | 0.21 | 2,098 | 0.19 | 11,395 | 0.19 | |

| 1,295,128 | 90.76 | 103,942 | 7.28 | 3,830 | 0.27 | 3,741 | 0.26 | 2,465 | 0.17 | 5,379 | 0.38 | 4,395 | 0.31 | 1,781 | 0.12 | 6,265 | 0.12 | |

| 149,488 | 83.17 | 10,187 | 5.67 | 6,570 | 3.66 | 2,974 | 1.65 | 4,251 | 2.37 | 3,304 | 1.84 | 677 | 0.38 | 1,580 | 0.88 | 710 | 0.88 | |

| 763,810 | 73.06 | 166,540 | 15.93 | 67,373 | 6.44 | 12,646 | 1.21 | 7,545 | 0.72 | 5,339 | 0.51 | 5,240 | 0.50 | 5,480 | 0.52 | 11,545 | 0.52 | |

| 338,335 | 71.37 | 70,211 | 14.81 | 37,408 | 7.89 | 7,772 | 1.64 | 4,142 | 0.87 | 3,696 | 0.78 | 3,526 | 0.74 | 4,286 | 0.9 | 4,663 | 0.90 | |

| 52,374 | 67.48 | 14,066 | 18.12 | 7,387 | 9.52 | 771 | 0.99 | 369 | 0.48 | 407 | 0.52 | 404 | 0.52 | 501 | 0.65 | 1 331 | 0.65 | |

| 452,480 | 93.38 | 20,133 | 4.15 | 5,006 | 1.03 | 1,121 | 0.23 | 1,171 | 0.24 | 1,658 | 0.34 | 1,141 | 0.24 | 1,222 | 0.25 | 628 | 0.25 | |

| 379,875 | 76.35 | 50,755 | 10.20 | 29,893 | 6.01 | 12 640 | 2.54 | 7 299 | 1.47 | 4 772 | 0.96 | 3 319 | 0.67 | 3 395 | 0.68 | 5 627 | 0.68 | |

| 114,833 | 81.66 | 16,399 | 11.66 | 2,734 | 1.94 | 2,117 | 1.51 | 937 | 0.67 | 632 | 0.45 | 675 | 0.48 | 502 | 0.36 | 1,790 | 0.36 | |

| 414,027 | 76.16 | 59,802 | 11.00 | 37,905 | 6.97 | 8,070 | 1.48 | 5,071 | 0.93 | 4,200 | 0.77 | 3,943 | 0.73 | 4,197 | 0.77 | 6,425 | 0.77 | |

| 112,401 | 69.44 | 27,432 | 16.95 | 13,733 | 8.48 | 2,210 | 1.37 | 1,159 | 0.72 | 1,131 | 0.70 | 966 | 0.60 | 912 | 0.56 | 1 920 | 0.56 | |

| 223,534 | 87.64 | 17,819 | 6.99 | 7,076 | 2.77 | 1,132 | 0.44 | 747 | 0.29 | 454 | 0.18 | 2,533 | 0.99 | 676 | 0.27 | 1,101 | 0.27 | |

| 216,899 | 73.04 | 33,693 | 11.35 | 23,254 | 7.83 | 6,777 | 2.28 | 5,215 | 1.76 | 3,201 | 1.08 | 1,927 | 0.65 | 2,343 | 0.79 | 3,656 | 0.79 | |

| 1,422,919 | 85.42 | 101,153 | 6.07 | 83,777 | 5.03 | 14,002 | 0.84 | 10,471 | 0.63 | 7,213 | 0.43 | 7,556 | 0.45 | 7,972 | 0.48 | 10,657 | 0.48 | |

| 426,385 | 65.78 | 119,389 | 18.42 | 60,414 | 9.32 | 11,199 | 1.73 | 5,435 | 0.84 | 5,354 | 0.83 | 4,485 | 0.69 | 4,612 | 0.71 | 10,969 | 0.71 | |

| 169,615 | 69.16 | 45,276 | 18.46 | 17,610 | 7.18 | 3 372 | 1.37 | 1,605 | 0.65 | 1,624 | 0.66 | 1,593 | 0.65 | 1,567 | 0.64 | 2,986 | 0.64 | |

| 600,404 | 76.23 | 94,785 | 12.02 | 53,569 | 6.79 | 10,884 | 1.38 | 5,060 | 0.64 | 4,363 | 0.55 | 4,095 | 0.52 | 3,916 | 0.5 | 10,824 | 0.50 | |

| 465,948 | 70.41 | 90,650 | 13.70 | 63,771 | 9.64 | 11,034 | 1.67 | 6,303 | 0.95 | 5,784 | 0.87 | 5,655 | 0.85 | 5,157 | 0.78 | 7,455 | 0.78 | |

| 290,716 | 71.44 | 46,094 | 11.33 | 41,680 | 10.24 | 8,179 | 2.01 | 4,080 | 1.00 | 3,809 | 0.94 | 3,215 | 0.79 | 3,234 | 0.79 | 5,908 | 0.79 | |

| 221,449 | 68.71 | 52,135 | 16.18 | 29,834 | 9.26 | 4,852 | 1.51 | 3,106 | 0.96 | 2,879 | 0.89 | 2,309 | 0.72 | 2,665 | 0.83 | 3,048 | 0.83 | |

| 2,564,012 | 81.35 | 316,316 | 10.04 | 144,008 | 4.57 | 30,697 | 0.97 | 16,461 | 0.52 | 21,413 | 0.68 | 17,100 | 0.54 | 15,876 | 0.5 | 26,090 | 0.50 | |

| 941,151 | 74.28 | 161,925 | 12.78 | 93,628 | 7.39 | 20,415 | 1.61 | 11,225 | 0.89 | 8,479 | 0.67 | 7,761 | 0.61 | 8,072 | 0.64 | 14,327 | 0.64 | |

| 318,703 | 73.30 | 59,425 | 13.67 | 38,002 | 8.74 | 4,590 | 1.06 | 2,313 | 0.53 | 2,178 | 0.50 | 3,020 | 0.69 | 2,682 | 0.62 | 3,873 | 0.62 | |

| 482,257 | 81.01 | 56,948 | 9.57 | 33,326 | 5.60 | 5,631 | 0.95 | 2,527 | 0.42 | 2,640 | 0.44 | 3,316 | 0.56 | 3,421 | 0.57 | 5,207 | 0.57 | |

| 703,423 | 79.01 | 78,545 | 8.82 | 48,465 | 5.44 | 18,715 | 2.10 | 10,719 | 1.20 | 8,129 | 0.91 | 5,655 | 0.64 | 6,136 | 0.69 | 10,539 | 0.69 | |

| 542,199 | 80.83 | 67,299 | 10.03 | 33,739 | 5.03 | 6,714 | 1.00 | 3,494 | 0.52 | 3,259 | 0.49 | 3,994 | 0.60 | 3,834 | 0.57 | 6,225 | 0.57 | |

| 53,341 | 72.30 | 10,364 | 14.07 | 6,185 | 8.34 | 1,007 | 1.36 | 491 | 0.67 | 458 | 0.62 | 408 | 0.55 | 417 | 0.57 | 1 108 | 0.57 | |

| 263,725 | 73.99 | 51,873 | 14.55 | 24,516 | 6.88 | 4,821 | 1.35 | 2,144 | 0.60 | 2,128 | 0.60 | 2,028 | 0.57 | 2,013 | 0.56 | 3,146 | 0.56 | |

| 406,480 | 85.35 | 33,894 | 7.12 | 20,758 | 4.36 | 3,561 | 0.75 | 1,726 | 0.36 | 1,636 | 0.34 | 2,781 | 0.58 | 1,863 | 0.39 | 3,549 | 0.39 | |

| 3,201,257 | 70.87 | 563,670 | 12.48 | 211,995 | 4.69 | 184,285 | 4.08 | 143,039 | 3.17 | 70,323 | 1.56 | 32,664 | 0.72 | 43,317 | 0.96 | 66,626 | 0.96 | |

| 2,758,911 | 74.49 | 476,897 | 12.88 | 203,869 | 5.50 | 78,893 | 2.13 | 49,664 | 1.34 | 36,133 | 0.98 | 24,523 | 0.66 | 26,448 | 0.71 | 48,175 | 0.71 | |

| 303,796 | 76.37 | 35,240 | 8.86 | 31,434 | 7.90 | 8,931 | 2.25 | 4,660 | 1.17 | 3,426 | 0.86 | 2,578 | 0.65 | 2,827 | 0.71 | 4,915 | 0.71 | |

| 17,863 | 71.15 | 3,397 | 13.53 | 2,482 | 9.89 | 448 | 1.78 | 158 | 0.63 | 172 | 0.69 | 135 | 0.54 | 185 | 0.74 | 267 | 0.74 | |

| 1,334,417 | 77.27 | 183,465 | 10.62 | 111,744 | 6.74 | 27,728 | 1.61 | 16,107 | 0.93 | 14,053 | 0.81 | 12,320 | 0.71 | 12,037 | 0.7 | 15,107 | 0.70 | |

| 377,648 | 81.51 | 51,026 | 11.01 | 13,954 | 3.01 | 1,034 | 0.22 | 1,017 | 0.22 | 5,699 | 1.23 | 8,398 | 1.81 | 1,071 | 0.23 | 3,470 | 0.23 | |

| 209,286 | 72.65 | 36,661 | 12.73 | 22,000 | 7.64 | 5,303 | 1.84 | 4,143 | 1.44 | 2,456 | 0.85 | 2,420 | 0.84 | 2,345 | 0.81 | 3,448 | 0.81 | |

| 926,958 | 71.06 | 213,707 | 16.39 | 85,790 | 6.58 | 21,067 | 1.62 | 14,654 | 1.12 | 9,080 | 0.70 | 8,005 | 0.61 | 8,473 | 0.65 | 16,625 | 0.65 | |

| 624,934 | 67.31 | 189,303 | 20.39 | 57,901 | 6.24 | 14,282 | 1.54 | 7,592 | 0.82 | 5,832 | 0.63 | 5,653 | 0.61 | 10,496 | 1.13 | 12,487 | 1.13 | |

| 731,838 | 72.97 | 155,156 | 15.47 | 67,777 | 6.76 | 11,539 | 1.15 | 5,748 | 0.57 | 6,003 | 0.60 | 7,846 | 0.78 | 6,137 | 0.61 | 10,938 | 0.61 | |

| 349,743 | 76.77 | 55,482 | 12.18 | 27,617 | 6.06 | 5,777 | 1.27 | 2,698 | 0.59 | 3,187 | 0.70 | 3,187 | 0.70 | 3,210 | 0.7 | 4,670 | 0.70 | |

| 625,928 | 79.98 | 78,135 | 9.98 | 43,823 | 5.60 | 9,048 | 1.16 | 4,697 | 0.60 | 4,037 | 0.52 | 5,614 | 0.72 | 4,616 | 0.59 | 6,740 | 0.59 | |

| 993,076 | 75.35 | 138,977 | 10.55 | 90,132 | 6.84 | 28,963 | 2.20 | 16,918 | 1.28 | 11,859 | 0.90 | 10,154 | 0.77 | 9,624 | 0.73 | 18,203 | 0.73 | |

| 589,384 | 65.26 | 193,166 | 21.39 | 63,754 | 7.06 | 15,079 | 1.67 | 8,019 | 0.89 | 6,676 | 0.74 | 5,814 | 0.64 | 6,605 | 0.73 | 14,571 | 0.73 | |

| 258,584 | 75.05 | 39,407 | 11.44 | 23,688 | 6.87 | 5,794 | 1.86 | 5,533 | 1.61 | 2,656 | 0.77 | 2,782 | 0.81 | 2,952 | 0.86 | 3,165 | 0.86 | |

| 1,641,189 | 78.97 | 236,287 | 11.37 | 106,905 | 5.14 | 23,036 | 1.11 | 13,761 | 0.66 | 13,046 | 0.63 | 14,121 | 0.68 | 11,741 | 0.56 | 18,200 | 0.56 | |

| 458,882 | 76.34 | 76,023 | 12.65 | 37,091 | 6.17 | 7,777 | 1.29 | 4,068 | 0.68 | 3,654 | 0.61 | 3 731 | 0.62 | 4,094 | 0.68 | 5,756 | 0.68 | |

| 1,735,236 | 75.01 | 209,112 | 9.04 | 94,569 | 4.09 | 100,059 | 4.33 | 73,532 | 3.18 | 36,254 | 1.57 | 15,295 | 0.66 | 20,450 | 0.88 | 28,951 | 0.88 | |

| 294,166 | 64.38 | 124,518 | 27.25 | 18,089 | 3.96 | 7,494 | 1.64 | 2,604 | 0.57 | 2,010 | 0.44 | 1,711 | 0.37 | 1,696 | 0.37 | 4,636 | 0.37 | |

| 153,289 | 66.92 | 41,201 | 17.99 | 20,075 | 8.76 | 3,874 | 1.69 | 1,938 | 0.85 | 1,654 | 0.72 | 1,496 | 0.65 | 1,586 | 0.69 | 3,942 | 0.69 | |

| 1,234,759 | 75.82 | 189,314 | 11.63 | 98,007 | 6.02 | 32,392 | 1.99 | 17,892 | 1.10 | 12,324 | 0.76 | 11,543 | 0.71 | 10,805 | 0.66 | 21,460 | 0.66 | |

| 987,373 | 78.33 | 148,585 | 11.79 | 66,254 | 5.26 | 15,067 | 1.20 | 9,268 | 0.74 | 7,485 | 0.59 | 8,326 | 0.66 | 7,436 | 0.59 | 10,736 | 0.59 | |

| 218,303 | 90.19 | 8,698 | 3.59 | 6,988 | 2.89 | 3,083 | 1.27 | 903 | 0.37 | 896 | 0.37 | 569 | 0.24 | 576 | 0.24 | 2,040 | 0.24 | |

| 347,859 | 73.49 | 62,351 | 13.17 | 36,894 | 7.79 | 6,724 | 1.42 | 3,426 | 0.72 | 3,304 | 0.70 | 3,519 | 0.74 | 3,894 | 0.82 | 5,399 | 0.82 | |

| 1,118,523 | 80.55 | 157,345 | 11.33 | 58,778 | 4.23 | 11,656 | 0.84 | 6,130 | 0.44 | 6,985 | 0.50 | 8,008 | 0.58 | 7,593 | 0.55 | 13,559 | 0.55 | |

| 1,555,532 | 74.60 | 241,365 | 11.58 | 141,683 | 6.79 | 44,258 | 2.12 | 27,144 | 1.30 | 19,428 | 0.93 | 13,317 | 0.64 | 15,154 | 0.73 | 27,282 | 0.73 | |

| 494,966 | 81.81 | 55,183 | 9.12 | 31,418 | 5.19 | 5,311 | 0.88 | 3,210 | 0.53 | 2,521 | 0.42 | 3,593 | 0.59 | 3,137 | 0.52 | 5,652 | 0.52 | |

| 1,854,119 | 82.09 | 204,618 | 9.06 | 67,929 | 3.01 | 29,951 | 1.33 | 19,643 | 0.87 | 13,361 | 0.59 | 37,969 | 1.68 | 13,030 | 0.58 | 18,045 | 0.58 | |

| 328,296 | 71.23 | 70,163 | 15.22 | 31,466 | 6.83 | 10,091 | 2.19 | 5,886 | 1.28 | 3,986 | 0.86 | 2,757 | 0.60 | 2,976 | 0.65 | 5,307 | 0.65 | |

| 648,117 | 79.20 | 77,552 | 9.48 | 48,748 | 5.96 | 11,689 | 1.43 | 7,537 | 0.92 | 5,331 | 0.65 | 5,379 | 0.66 | 5,692 | 0.7 | 8,333 | 0.70 | |

| 150,795 | 91.98 | 5,762 | 3.51 | 2,809 | 1.71 | 1,779 | 1.09 | 451 | 0.28 | 339 | 0.21 | 439 | 0.27 | 406 | 0.25 | 1,160 | 0.25 | |

| 459,198 | 74.55 | 77,050 | 12.51 | 43,421 | 7.05 | 10,144 | 1.65 | 5,635 | 0.91 | 4,846 | 0.79 | 4,902 | 0.80 | 4,718 | 0.77 | 6,027 | 0.77 | |

| 672,385 | 79.75 | 69,294 | 8.22 | 64,376 | 7.63 | 11,723 | 1.39 | 4,808 | 0.57 | 4,577 | 0.54 | 4,249 | 0.50 | 4,543 | 0.54 | 7,152 | 0.54 | |

| 571,623 | 76.23 | 84,981 | 11.33 | 50,859 | 6.78 | 11,518 | 1.54 | 5,142 | 0.69 | 6,188 | 0.83 | 5,301 | 0.71 | 4,958 | 0.66 | 9,308 | 0.66 | |

| 477,654 | 74.27 | 94,809 | 14.74 | 40,028 | 6.22 | 7,146 | 1.11 | 3,567 | 0.55 | 4,197 | 0.65 | 4,752 | 0.74 | 3,972 | 0.62 | 7,023 | 0.62 | |

| 546,042 | 73.65 | 93,649 | 12.63 | 58,822 | 7.93 | 10,777 | 1.45 | 6,147 | 0.83 | 6,098 | 0.82 | 5,075 | 0.68 | 5,440 | 0.73 | 9,351 | 0.73 | |

| 929,541 | 77.55 | 140,708 | 11.74 | 69,909 | 5.83 | 14,403 | 1.20 | 10,242 | 0.85 | 6,851 | 0.57 | 8,116 | 0.68 | 8,040 | 0.67 | 10,850 | 0.67 | |

| 453,576 | 72.41 | 75,644 | 12.08 | 54,556 | 8.71 | 13,365 | 2.13 | 8,048 | 1.28 | 5,333 | 0.85 | 4,567 | 0.73 | 5,184 | 0.83 | 6,090 | 0.83 | |

| 952,642 | 78.88 | 136,435 | 11.30 | 64,905 | 5.37 | 13,024 | 1.08 | 7,561 | 0.63 | 7,277 | 0.60 | 8,561 | 0.71 | 7,830 | 0.65 | 9,435 | 0.65 | |

| Voting abroad | 403,306 | 85.02 | 23,871 | 5.03 | 8,224 | 1.73 | 19,203 | 4.05 | 7,433 | 1.57 | 3,079 | 0.65 | 1,439 | 0.30 | 2,010 | 0.42 | 5,801 | 0.42 |

| 291,409 | 85.54 | 19,448 | 5.72 | 19,409 | 5.70 | 2,394 | 0.70 | 1,367 | 0.40 | 1,154 | 0.34 | 1,794 | 0.53 | 1,052 | 0.31 | 2,616 | 0.31 | |

| 472,666 | 71.84 | 85,256 | 12.96 | 49,621 | 7.54 | 15,607 | 2.37 | 11,738 | 1.78 | 6,710 | 1.02 | 4,377 | 0.67 | 5,329 | 0.81 | 6,636 | 0.81 | |

| 329,911 | 72.03 | 62,375 | 13.62 | 45,804 | 10.00 | 4,750 | 1.04 | 2,095 | 0.46 | 2,111 | 0.46 | 2,772 | 0.61 | 2,450 | 0.53 | 5,767 | 0.53 | |

| 56,430,712 | 76.69 | 8,659,206 | 11.77 | 4,154,985 | 5.65 | 1,238,031 | 1.68 | 769,644 | 1.05 | 556,801 | 0.76 | 499,342 | 0.68 | 479,013 | 0.65 | 791,258 | 1.08 | |

| Source: CEC | ||||||||||||||||||

Reactions

[edit]India was the first world power to react to the election results, saying in a congratulatory message to Putin that it vowed to push ties with Russia to a "higher level."[164] Other countries which sent their congratulations included: Azerbaijan, Armenia, Belarus, Bolivia, Bulgaria, Croatia,[165] Cuba, Czech Republic, Egypt, Guatemala,[166] Hungary, China,[164] Iran, Israel,[167] Japan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Malaysia,[168] Moldova, North Korea,[169] Philippines,[170] Saudi Arabia, Serbia,[171] Singapore,[172] Sudan,[173] Syria, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, United States,[174] Uzbekistan and Venezuela.[175]

Western reaction to the election result was predominantly muted as the election came at a time of heightened tensions between the West and Russia due to the poisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripal, the ongoing U.S. investigation of the alleged Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections and a series of other issues.[176] The European Union said that violations and shortcomings in the election flouted international standards while the White House deputy press secretary Hogan Gidley initially said that there was no congratulatory phone call scheduled between U.S. president Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin.[176][177][164] Donald Trump later congratulated Putin in a phone call while the president of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker later congratulated Putin;[178][179] their actions in turn drew criticism.[180][181][182][183] France and Germany acknowledged Putin's victory but both countries avoided explicitly using the word "congratulate", instead "wishing success" to Putin for his new six-year term in office.[180]

Voting irregularities were reported by an independent election monitoring group Golos. Edward Snowden criticized what he claimed was ballot stuffing and Russian opposition entities Alexei Navalny and Open Russia criticized what they alleged to be voting fraud.[185][176] Ella Pamfilova, the head of the Central Electoral Commission, said that there were no serious violations and those involved in the violations would be caught; she later said that Putin's level of support showed that society had united in the face of pressure from abroad.[185][176] According to one monitor group who observed voters in several voting stations which showed "suspicious" results in previous elections, the actual turnout at these stations was 21-34% while official results from these stations showed 76-86% (in one station 8,765 physical voters were counted, official results showed 13,235 votes). The group concluded that in these elections the government and local administration officers chose to simply falsify the voting protocols rather than use easy-to-spot ballot stuffing or carousel voting.[186] Election statistician Sergey Shpilkin said that while this election was slightly "cleaner" than the preceding ones, there were around 10 million votes added in favor of Putin illegally.[187]

Prominent Russian dissident[188] Garry Kasparov said that the elections were a "charade."[189]

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) said that the election "took place in an overly controlled legal and political environment marked by continued pressure on critical voices, while the Central Election Commission (CEC) administered the election efficiently and openly."[190]

The head observer of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation described the election as "transparent, credible, democratic" while Maxim Grigoriev, deputy head of the monitoring group of the Civic Chamber of the Russian Federation called it "unprecedentedly clean".[185]

References

[edit]- ^ https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-42479909

- ^ "Alexei Navalny: Russian opposition leader found guilty of embezzlement". theguardian.com. 8 February 2017. Archived from the original on 25 August 2024. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ "Russian opposition leader's fraud conviction arbitrary, Europe's top rights court says". reuters.com. 17 October 2017. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ "Alexei Navalny: Russia's vociferous Putin critic". bbc.com. 15 March 2018. Archived from the original on 17 February 2024. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ Stefanov, Mike (22 December 2008). "Russian presidential term extended to 6 years". CNN. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ Chapter 4. The President of the Russian Federation Archived 16 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Constitution of the Russian Federation.

- ^ "Совет Федерации объявил начало кампании по выборам президента России". Meduza (in Russian). Archived from the original on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ Поправки в законы о выборах могут принять к июню, считает Клишас (in Russian). RIA Novosti. 7 March 2017. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ Федеральный закон от 10.01.2003 г. № 19-ФЗ. Kremlin.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 8 May 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ "Russia To Move 2018 Presidential Vote To Day Marking Seizure of Crimea". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 13 April 2017. Archived from the original on 26 April 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ "Внесены изменения в закон о выборах Президента Российской Федерации". Президент России (in Russian). Archived from the original on 5 October 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ "Campaign officially starts for Russia's presidential election". The Japan News. 19 December 2017. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017.

- ^ "Russian presidential election 2018". TASS. 19 March 2018. Archived from the original on 25 August 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ^ "Доклад Алексея Журавлева на III Съезде партии "РОДИНА"". rodina.ru. Archived from the original on 22 November 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ a b ""Гражданская платформа" поддержит Путина на выборах президента России". ТАСС. Archived from the original on 17 September 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ^ ""Справедливая Россия" поддержит Путина на выборах президента". РБК. 24 December 2017. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ Совет Федерации объявил начало кампании по выборам президента России. Meduza (in Russian). Archived from the original on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ "Госпожа претендент". Газета "Коммерсантъ". 19 October 2017. p. 1. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ "В ЦИК ожидают большого количества желающих баллотироваться в президенты". ТАСС. Archived from the original on 14 December 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ Рост. primaries.rost.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "Члены Партии роста предложили Путину уйти с поста президента". РБК. 10 August 2017. Archived from the original on 25 August 2024. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "Борис Титов объявил об участии в выборах президента России". Ведомости. 26 November 2017. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ Кандидат 2018 – Левый Фронт. Кандидат 2018 – Левый Фронт (in Russian). Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ Кандидат 2018 – Левый Фронт. Кандидат 2018 – Левый Фронт (in Russian). Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ Десять непарламентских партий объединились в блок "Третья сила". Ридус (in Russian). Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "Третья сила" "выкристаллизирует" до четырех кандидатов в президенты РФ. ИА REGNUM (in Russian). Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ Третья сила. Ruposters.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ Победители без побеждённых. EG.RU (in Russian). Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "Ирина Волынец отказалась баллотироваться в президенты". Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ Полищук снял свою кандидатуру с выборов президента. Российская газета (in Russian). 31 January 2018. Archived from the original on 31 January 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "Кандидаты на должность Президента Российской Федерации". cikrf.ru. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ a b "Российский общенародный союз" выдвинул Бабурина кандидатом в президенты. РИА Новости (in Russian). 22 December 2017. Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ a b Бабурин подал в ЦИК документы для выдвижения в президенты от своей партии. РИА Новости (in Russian). 24 December 2017. Archived from the original on 24 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ a b ЦИК предложил трем потенциальным кандидатам устранить нарушения при выдвижении. РИА Новости (in Russian). 25 December 2017. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ a b ЦИК разрешил Бабурину открыть избирательный счет и начать сбор подписей. ТАСС (in Russian). Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ ЦИК зарегистрировал Бабурина кандидатом на пост президента (in Russian). РИА Новости. 7 February 2018. Archived from the original on 8 February 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ a b "КПРФ может выдвинуть в президенты главу "Совхоза имени Ленина" Грудинина". ng.ru. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ СМИ: КПРФ может выдвинуть кандидатом в президенты не Зюганова (in Russian). 21 December 2017. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ Громов, Алексей. "Не Зюганов: КПРФ и НПСР выдвинут единого кандидата на президентские выборы-2018". Федеральное агентство новостей No.1. Archived from the original on 2 October 2020. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Зюганов раскрыл ЦК партии причины отказа от президентской гонки". РБК. 23 December 2017. Archived from the original on 2 October 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ Жириновский назвал достойной кандидатуру Грудинина от КПРФ на пост президента. РИА Новости (in Russian). 23 December 2017. Archived from the original on 1 January 2018. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ Наумкина, Катерина. "Зюганов возглавит предвыборный штаб кандидата от КПРФ Грудинина". Народные Новости России. Archived from the original on 2 October 2020. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ ЦИК принял документы Грудинина для выдвижения кандидатом в президенты. РИА Новости (in Russian). 28 December 2017. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ ЦИК получил документы для регистрации Грудинина кандидатом в президенты. РИА Новости (in Russian). 9 January 2018. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ ЦИК зарегистрировал выдвинутого КПРФ Грудинина кандидатом в президенты. ТАСС (in Russian). Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- ^ Жириновский объявил о своем участии в выборах президента в 2018 году | Zhirinovsky declares his participation in 2018 presidential election Archived 9 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine. RBK. Published 15 June 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2017. (in Russian)

- ^ Жириновский не исключил, что ЛДПР на выборах президента представит не он | Zhirivonsky doesn't rule out someone else representing LDPR in election Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Life.ru. Published 23 July 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2017. (in Russian)

- ^ Жириновский пойдёт на выборы президента с четырьмя преемниками | Zhirinovsky to go into election with four successors Archived 25 August 2024 at the Wayback Machine. Life.ru. Published 2 March 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2017. (in Russian)

- ^ a b Владимир Жириновский: я буду защищать русских везде | I will protect Russians everywhere Archived 29 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine. LDPR official website. Published 28 October 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2017. (in Russian)

- ^ Владимир Жириновский снова собрался в президенты | Vladimir Zhirinovsky again running for presidency Archived 28 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Kommersant. Published 28 October 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2017. (in Russian)

- ^ "Жириновский в шестой раз поборется за пост президента России". РБК. 20 December 2017. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ "Жириновский подал в ЦИК документы на выдвижение кандидатом в президенты". РБК. 21 December 2017. Archived from the original on 22 October 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ В ЦИК поступили документы для регистрации Жириновского кандидатом в президенты России. ТАСС (in Russian). Archived from the original on 3 January 2018. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ Президентские выборы в РФ: статистические показатели. Досье. ТАСС (in Russian). Archived from the original on 16 January 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ Жириновский стал первым официально зарегистрированным кандидатом в президенты. РИА Новости (in Russian). 29 December 2017. Archived from the original on 6 December 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ "Putin to run again for Russia president". BBC News. 6 December 2017. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ "Putin says will run as an independent candidate for new Kremlin term". Reuters. 14 December 2017. Archived from the original on 2 October 2020. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ "Celebrity-Laden Action Group Officially Nominates Putin As Candidate For Russian Presidency". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 26 December 2017. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018.

- ^ Путин подал документы в Центризбирком. РИА Новости (in Russian). 27 December 2017. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ ЦИК зарегистрировал уполномоченных Путина и дал ему разрешение открыть избирательный счет. ТАСС (in Russian). Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ ЦИК проверил подписи в поддержку Путина. ТАСС (in Russian). Archived from the original on 13 August 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "ЦИК зарегистрировал Владимира Путина кандидатом в президенты". 6 February 2018. Archived from the original on 2 October 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ Walker, Shaun (18 October 2017). "Putin mentor's daughter Ksenia Sobchak to run for president". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ Собчак может стать самым молодым выдвиженцем с 2004 года. РИА Новости (in Russian). 19 October 2017. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ "Russian socialite in presidential bid". BBC News. 18 October 2017. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ "Daughter of Putin Mentor Nominated By Opposition Party For Presidential Vote". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 23 December 2017. Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ "Собчак подала в ЦИК документы о выдвижении кандидатом в президенты". Meduza (in Russian). Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ ЦИК разрешил Собчак открыть избирательный счет и начать сбор подписей. ТАСС (in Russian). 26 December 2017. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ "Ксения Собчак зарегистрирована кандидатом в президенты России". 8 February 2018. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ Партия «Коммунисты России» определилась с кандидатом в президенты | Party "Communists of Russia" decide on a candidate for the presidency Archived 7 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Gazeta.ru. Published 1 February 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2017. (in Russian)

- ^ "КОММУНИСТЫ РОССИИ – ОФИЦИАЛЬНЫЙ САЙТ / Новости / России необходим сталинский президент-коммунист! 6-й съезд Партии КОММУНИСТЫ РОССИИ выдвинул ТОВАРИЩА МАКСИМА кандидатом в президенты страны!". komros.info. Archived from the original on 24 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ Сурайкин подал в ЦИК документы для выдвижения в президенты. РИА Новости (in Russian). 24 December 2017. Archived from the original on 24 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ ЦИК утвердил документы Сурайкина на выдвижение в президенты. РИА Новости (in Russian). 25 December 2017. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ "ЦИК зарегистрировал Максима Сурайкина кандидатом в президенты России". 8 February 2018. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ "Борис Титов объявил об участии в выборах президента России". Ведомости. 26 November 2017. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Партия роста выдвинула в президенты омбудсмена Бориса Титова". РБК. 21 December 2017. Archived from the original on 25 May 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ a b Титов подал в ЦИК документы для выдвижения кандидатом в президенты. РИА Новости (in Russian). 22 December 2017. Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ ЦИК утвердил документы Титова на выдвижение в президенты. РИА Новости (in Russian). 25 December 2017. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ ЦИК зарегистрировал Титова кандидатом на пост президента (in Russian). РИА Новости. 7 February 2018. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ a b Yabloko plans to nominate Yavlinsky again in the 2018 presidential election Archived 7 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Interfax. Published 17 February 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ^ a b Gorbachev, Alexei (21 March 2017). Явлинский отказался от традиционной предвыборной кампании | Yavlinsky refused a traditional election campaign Archived 23 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Nezavisimaya Gazetta. Retrieved 2 May 2017. (in Russian)

- ^ Съезд "Яблока" выдвинул Явлинского кандидатом в президенты. РИА Новости (in Russian). 22 December 2017. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ Явлинский подал в ЦИК документы для выдвижения кандидатом в президенты. РИА Новости (in Russian). 22 December 2017. Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ ЦИК утвердил документы Явлинского для выдвижения на выборы. РИА Новости (in Russian). 25 December 2017. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ ЦИК зарегистрировал Явлинского кандидатом на пост президента (in Russian). РИА Новости. 7 February 2018. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ "Сергей Бабурин начал собирать подписи – ПРЕЗИДЕНТ.ИНФО-Выборы президента России 2018". 9 January 2018. Archived from the original on 5 February 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ^ "Кандидат в президенты Бабурин рассказал о своей предвыборной кампании". 9 January 2018. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ^ "Бабурин сдаст подписи для регистрации кандидатом в президенты РФ 30 января". Archived from the original on 5 February 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ^ "ЦИК зарегистрирует кандидатами в президенты Путина, Явлинского, Титова и Бабурина". 5 February 2018. Archived from the original on 8 March 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ^ СМИ: КПРФ может выдвинуть кандидатом в президенты не Зюганова (in Russian). 21 December 2017. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ Громов, Алексей. "Не Зюганов: КПРФ и НПСР выдвинут единого кандидата на президентские выборы-2018". Федеральное агентство новостей No.1. Archived from the original on 2 October 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ "Съезд КПРФ утвердил кандидатуру Грудинина на выборах президента РФ". РЕН ТВ. 23 December 2017. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ Пора выбирать: Алексей Навальный — кандидат в президенты России Archived 12 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine – via YouTube. Published 2 March 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017. (in Russian)

- ^ Tumakova, Irina, and Pavlovsky, Gleb (22 April 2017) «Навальный ударил, а Кремль залез в угол и плюётся» Archived 2 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Fontanka.ru. Retrieved 30 April 2017. (in Russian)

- ^ Bennetts, Marc (17 April 2017). Alexei Navalny: Is Russia's Anti-Corruption Crusader Vladimir Putin's Kryptonite? Archived 12 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Newsweek. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ Tamkin, Emily (2 March 2017). Navalny's Anti-Corruption Fund Accuses Medvedev of Secret Massive Estate Archived 27 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Foreign Policy. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ Он вам не Димон – via YouTube. Published 2 March 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ 26 марта все на улицу: он нам не Димон Archived 21 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine – via YouTube. Published 23 March 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017. (in Russian)

- ^ Кремль на развилке: каковы последствия протестных акций по всей России Archived 26 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Rbk.ru. Published 26 March 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017. (in Russian)

- ^ Filipov, David (26 March 2017). Russian police arrest anti-corruption leader Navalny, hundreds more in nationwide rallies Archived 6 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Washington Post. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ Anastasia Uditskaya; Sergei Vitko; Evgeniya Kuznetsova (12 April 2017). Навальный сообщил о подготовке новой протестной акции (in Russian). Rbk.ru. Archived from the original on 14 April 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ^ Программа — Алексей Навальный (in Russian). Archived from the original on 22 March 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ Pyotr Orekhin (21 December 2016). Экономика не выдержит Навального (in Russian). Gazetta.ru. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ Sergei Aleksashenko (15 December 2016). "Alexei Navalny's Program. Economist's Analysis" (in Russian). Republic. Archived from the original on 26 April 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ Arseny Tomin (18 April 2017). Навальный собрал необходимые 300 тыс подписей для выборов президента (in Russian). Moskovsky Komsomolets. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ Rothrock, Kevin (25 April 2017). How Alexey Navalny Abandoned Russian Nationalism Archived 3 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Global Voices. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ Russia Navalny: Supreme court overturns conviction for fraud Archived 22 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine. BBC. Published 16 November 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ Russian Activist Navalny Given 5-Year Suspended Sentence in Kirovles Retrial Archived 17 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Moscow Times. Published 8 February 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ Yegorov, Oleg (3 May 2017). Russia's opposition figure 'cannot run for president' Archived 16 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Russia Beyond the Headlines. Published 3 May 2017.

- ^ Kremlin critic Navalny can't run for presidency – election official Archived 13 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Reuters. Published 3 May 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ^ "Памфилова рассказала о двух возможных вариантах регистрации Навального". РБК. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ "Глава ЦИК напутствовала Навального на выборы фразой "флаг в руки"". РБК. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ "Радио ЭХО Москвы :: Новости / Правозащитный центр Мемориал признал Алексея Навального политическим заключенным". Echo.msk.ru. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ^ Sokolovskaya, Evgenia. (March 2018) Russia Chooses Its Leader: How Putin Sets the Stage to Win Archived 7 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine The Globe Post. Retrieved 6 March 2018

- ^ Walker, Shaun (7 December 2017). Navalny's army: the Russians risking all to oppose Vladimir Putin Archived 25 August 2024 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ Navalny's Campaign Chief Gets 30 Days In Jail In Nizhny Novgorod Archived 9 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Published 1 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ Президентская программа Алексея Навального. В одной картинке. Meduza (in Russian). Archived from the original on 14 December 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ "Russian presidential election: Alexei Navalny barred from competing". BBC News. 25 December 2017. Archived from the original on 20 March 2024. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ Владимир Путин: Я буду баллотироваться на пост президента РФ. Российская газета (in Russian). 6 December 2017. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ "Миронов призвал не допустить в новое правительство "либеральных людоедов"". РБК. 25 December 2017. Archived from the original on 2 October 2020. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ Партия "Зеленые" завила, что поддержит Путина на выборах президента. РИА Новости (in Russian). 26 December 2017. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ "Партия Великое Отечество на выборах Президента поддержит В.В. Путина". Archived from the original on 22 October 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ Плющев, Геннадий. "Трудовая партия России поддержит кандидатуру Путина на выборах-2018". Федеральное агентство новостей No.1. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ [Party of Pensioners "Партия пенсионеров" не станет выдвигать кандидата на выборах президента РФ]

- ^ "Патриоты России" намерены поддержать Путина на выборах президента. ТАСС (in Russian). Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ Лидер "Родины" заявил о поддержке кандидатуры Путина на выборах. ИА REGNUM (in Russian). Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ "Единая Россия" поддержит кандидатуру Путина на выборах президента (in Russian). 6 December 2017. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ "A Female Candidate For A 'Predictable Election'? Kremlin Floats Women Challengers To Putin". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 2 September 2017. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ ""Если Навального зарегистрируют, я сниму свою кандидатуру": первое интервью кандидата в президенты Ксении Собчак". TV Rain (in Russian). 18 October 2017. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ "Штаб Собчак обсудил три схемы выдвижения в президенты". РБК. 30 October 2017. Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ "Ксения Собчак пойдет на выборы от партии бывшего министра". РБК. 15 November 2017. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ Ксения Собчак выдвинута кандидатом в президенты РФ от "Гражданской инициативы". Новости. Первый канал (in Russian), archived from the original on 2 October 2020, retrieved 9 January 2018

- ^ Команда Собчак начала сбор подписей в ее поддержку на выборах президента. РИА Новости (in Russian). 27 December 2017. Archived from the original on 1 January 2018. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ ""Коммунисты России" намерены выдвинуть кандидата на выборах президента". 25 December 2016. Archived from the original on 5 February 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ "Народный штаб Павла Грудинина – Левый Фронт". Народный штаб Павла Грудинина – Левый Фронт. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ ""Коммунисты России" выдвинули Сурайкина кандидатом на выборы президента РФ". Archived from the original on 8 February 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ Рост. primaries.rost.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ "Борис Титов объявил об участии в выборах президента России". Ведомости. 26 November 2017. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ "Титов назвал главную задачу своего выдвижения на выборы президента России". РБК. 26 November 2017. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ ЦИК утвердил документы Титова на выдвижение в президенты. РИА Новости (in Russian). 25 December 2017. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ В 'Партии роста' рассказали, когда начнут сбор подписей в поддержку Титова. РИА Новости (in Russian). 25 December 2017. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ Yavlinsky's campaign for President of Russia picks up Archived 7 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Yabloko website. Published 23 February 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ Yavlinsky spoke about his election program for the elections-2018 Archived 7 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Russian Reality. Published 21 March 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ^ Bolgova, Ekaterina (4 February 2017). Партия «Яблоко» объявила о старте предвыборной кампании Явлинского | Yabloko Party announced the start of Yavlinsky's election campaign. Komsomolskaya Pravda. Retrieved 2 May 2017. (in Russian).

- ^ "Григорию Явлинскому помогут Михеич и Алексеич". Коммерсантъ. 11 January 2017. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ "Жириновский обещает всеобщую амнистию в случае победы на выборах президента". 22 March 2017. Archived from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ "Центризбирком распределил время для дебатов между СМИ". 14 February 2018. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.