Pulse nightclub shooting

| Pulse nightclub shooting | |

|---|---|

| Part of mass shootings in the United States, violence against LGBT people in the United States, and Islamic terrorism in the United States | |

The scene of the shooting | |

| Location | Pulse nightclub 1912 S. Orange Avenue Orlando, Florida, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 28°31′10.5″N 81°22′36.5″W / 28.519583°N 81.376806°W |

| Date | June 12, 2016 2:02 a.m. – 5:14 a.m. EDT (UTC−04:00) |

| Target | Patrons of Pulse nightclub |

Attack type | |

| Weapons | |

| Deaths | 50 (including the perpetrator) |

| Injured | 58 (53 by gunfire)[1] |

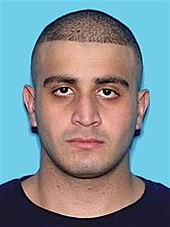

| Perpetrator | Omar Mateen |

| Motive | Islamic extremism |

| Verdict | Perpetrator's wife |

| Charges | Perpetrator's wife

|

On June 12, 2016, 29-year-old Omar Mateen shot and killed 49 people and wounded 53 more in a mass shooting at Pulse, a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida, United States before Orlando Police officers fatally shot him after a three-hour standoff.

In a 911 call made shortly after the shooting began, Mateen swore allegiance to the leader of the Islamic State, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, and said the U.S. killing of Abu Waheeb in Iraq the previous month "triggered" the shooting.[2] He later told a negotiator he was "out here right now" because of the American-led interventions in Iraq and in Syria and that the negotiator should tell the United States to stop the bombing. The incident was deemed a terrorist attack by FBI investigators.

Pulse was hosting a "Latin Night," and most of the victims were Latino. The shooting was the deadliest terrorist attack in the United States since the September 11 attacks, and the deadliest mass shooting in modern U.S. history until the 2017 Las Vegas shooting.

Shooting

[edit]First shots and hostage situation

[edit]On June 11, 2016, Pulse, a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida, was hosting "Latin Night," a weekly Saturday night event drawing a primarily Latino crowd.[3][4] RuPaul’s Drag Race contestant and drag queen Kenya Michaels is recorded to have been performing right as the shooting began (Michaels survived the shooting).[5] About 320 people were still inside the club, which was serving last call drinks at around 2:00 a.m. EDT on June 12.[6][7] At around the same time, Omar Mateen arrived at the club via rental van, parking it in the parking lot of a neighboring car shop.[1][8] He got out and walked toward the building armed with a SIG Sauer MCX[9] semi-automatic rifle and a 9mm Glock 17 semi-automatic pistol.[10][11][12][13] He was wearing a green, blue, and white plaid dress shirt, a white T-shirt underneath, and tan cargo pants.[1] At 2:02 a.m., Mateen bypassed Officer Adam Gruler, a uniformed off-duty Orlando Police Department (OPD) officer working extra duty[14][15] as a security guard, entered the building through its southern entrance, and began shooting patrons.[1][6][7][16] Dozens were killed or severely injured inside the crowded nightclub, either directly or by ricochets.[1][17]

Gruler took cover and called in a signal for assistance. He told a post-incident Police Foundation assessment team that he had immediately recognized that his handgun would be severely disadvantaged against the rifle Mateen was using.[1] When he witnessed Mateen shooting two patrons attempting to escape through an emergency exit, Gruler fired shots at him.[1][16][18] In response, Mateen withdrew back into the nightclub and continued shooting victims as he traversed through the building, sometimes firing into bodies without checking whether they were already dead.[1] When additional officers arrived at the nightclub beginning at 2:04 a.m., Gruler shouted "[The gunman]'s in the patio!" and resumed firing at Mateen a minute later.[1][15][19] Two officers joined Gruler in engaging Mateen, who then retreated farther into the nightclub and "began a 'hostage situation'" in one of the bathrooms.[1][6][20][21] In less than five minutes, Mateen had fired approximately 200 rounds, pausing only to reload.[1]

During the shooting, some of the people trapped inside the club sought help by calling or sending text messages to friends and relatives. Initially, some of them thought the gunshots were firecrackers or part of the music.[22][23][24] Imran Yousuf, a recently discharged Marine Corps veteran working as a nightclub bouncer immediately recognized the sounds as gunfire, which he described as "high caliber," and jumped over a locked door behind which dozens of people were hidden and paralyzed by fear, then opened a latched door behind them, allowing approximately 70 people to escape.[25][26] Many described a scene of panic and confusion caused by the loud music and darkness. One person shielded herself by hiding inside a bathroom and covering herself with bodies. A bartender said she took cover beneath the glass bar. At least one patron tried to help those who were hit.[27] According to a man trapped inside a bathroom with fifteen other patrons, Mateen fired sixteen times into the bathroom, through the closed door, killing at least two and wounding several others.[28]

According to one of the hostages, Mateen entered a bathroom in the nightclub's northwest side and opened fire on the people hiding there, wounding several. The hostage, who had taken cover inside a stall with others, was injured by two bullets and struck with flying pieces of a wall hit by stray bullets. Shortly after entering the women's restroom, Mateen's rifle jammed. He then discarded the rifle and switched to his Glock 17 pistol.[29][30][31] Two survivors quoted Mateen as saying, "I don't have a problem with black people,"[32][33] and that he "wouldn't stop his assault until America stopped bombing his country."[34] Other survivors heard Mateen claim he had explosives as well as snipers stationed around the club.[35]

Patrons trapped inside called or texted 911 to warn of the possible presence of explosives.[36]

Emergency response

[edit]Over the next 45 minutes, about 100 officers from the OPD and the Orange County Sheriff's Office were dispatched to the scene.[21] Among the earliest first responders to arrive were a firefighter crew from Fire Station 5 and two supporting firefighter paramedics from Fire Station 7. Eighty fire and emergency medical services personnel from the Orlando Fire Department were deployed during the entire incident.[37]

At 2:09 a.m., several minutes after the gunfire began, the club posted on its Facebook page, "Everyone get out of pulse [sic] and keep running."[38] At 2:22 a.m., Mateen placed a 911 call, during which he mentioned the Boston Marathon bombers—Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev—as his "homeboys" and made a reference to Moner Mohammad Abu Salha, an American citizen who died in a suicide bombing in Syria in 2014.[21][39][40] Mateen said he was inspired by Abu Salha's death for the Al-Nusra Front targeting Syrian government troops (a mutual enemy of the two Salafist groups, despite their history of violence with each other), and swore allegiance[41] to IS leader al-Baghdadi.[42] The FBI said that Mateen and Abu Salha had attended the same mosque and knew each other "casually."[43] Mateen made two other 911 calls during the shooting.[40] Numerous 911 calls were made by the patrons inside the nightclub around this time.[44]

After the initial rounds of gunfire between Mateen and Gruler, six officers shot out a large glass window and followed the sound of shooting to the bathroom area. When Mateen stuck his head out from one of the bathrooms, at least two officers shot at him. After the gunfire stopped, they were ordered to hold position instead of storming the bathroom, according to one of the officers.[16][29][45] After about 15 to 20 minutes, SWAT arrived and had the officers withdraw as the officers were "not really in tactical gear." SWAT then took over the operation.[45] When asked why the officers didn't proceed to the bathroom and engage Mateen, Orlando Police Chief John Mina said it was because Mateen "went from an active shooter to a barricaded gunman" and had hostages. He also noted, "If he had continued shooting, our officers would have went in there."[29] At that time, the last shot by Mateen was fired between 2:10 a.m. and 2:18 a.m.[46]

Rescues of people trapped inside the nightclub commenced and continued throughout the night. Because so many people were lying on the dance floor, one rescuing officer demanded, "If you're alive, raise your hand."[17] By 2:35 a.m., police had managed to extract nearly all of the injured from the nightclub. Those who remained included the hostages held by Mateen in the bathroom, as well as a dozen people who were hiding inside dressing rooms.[47]

Phone calls and negotiations

[edit]At 2:45 a.m., Mateen called News 13 of Orlando and said, "I'm the shooter. It's me. I am the shooter." He then said he was carrying out the shooting on the behalf of IS and began speaking rapidly in Arabic.[48][49] Mateen also said the shooting was "triggered" by a U.S.-led bombing strike in Iraq that killed Abu Wahib, an IS military commander, on May 6.[50]

A crisis negotiator was present as Mateen was held up inside and holding hostages.[51][52] Officers initially believed he was armed with a "suspicious device" that posed a threat, but it was later revealed to be a battery that fell out of an exit sign or smoke detector.[53]

Police hostage negotiators spoke with Mateen by telephone three times between 2:48 a.m. and 3:27 a.m.[54] He claimed during one of the calls that he had bombs strapped to his body.[51][54] He also claimed that he "had a vehicle in the parking lot with enough explosives to take out city blocks."[17] At 3:58 a.m., the OPD publicly announced the shooting and confirmed multiple injuries.[21] At 4:21 a.m., eight of the hostages escaped after police had removed an air conditioning unit from an exterior wall.[21][54] At approximately 4:29 a.m., Mateen told negotiators that he planned to strap explosive vests, similar to those used in the November 2015 Paris attacks, to four hostages, strategically place them in different corners of the building, and detonate them in 15 minutes.[1][36][51] OPD officers then decided to end negotiations and prepared to blow their way in.[21][22][51]

At around 2:30 a.m., Mateen's wife—after receiving a call from her mother at approximately 2:00 a.m. asking where her husband was—sent a text message to Mateen asking where he was. Mateen texted back asking her if she had seen the news. After she replied, "No?," Mateen responded, "I love you, babe." According to one source, she texted him back at one point saying that she loved him. She also called him several times during the standoff, but he did not answer. She found out about what was happening at 4:00 a.m. after the police told her to come out of her house with her hands up.[55][56]

A survivor of the shooting recalled Mateen saying he wanted the United States to "stop bombing his country."[57][58] The FBI said Mateen "told a negotiator to tell America to stop bombing Syria and Iraq and that was why he was 'out here right now.'"[54] During the siege, Mateen made Internet searches on the shooting, while police dispatched a tactical robot to discreetly enter the restroom and allow them to communicate with hostages via two-way audio.[1]

Rescue and resolution

[edit]

The FBI reported that no shots were heard between the time Mateen stopped exchanging gunfire with the first responders and 5:02 a.m., when Orlando police began breaching the building's wall.[54] Just before the breach, Mateen entered a women's bathroom where the hostages were hiding and opened fire, killing a man who sacrificed his life to save the woman behind him and at least one other, according to witnesses.[29][30]

At 5:07 a.m., fourteen SWAT officers—after failing to blow open a big enough hole in the bathroom's exterior wall using a bomb due to the wall's structure[1]—successfully breached the building when a policeman drove a BearCat armored vehicle through a wall in the northern bathroom. They then used two flashbangs to distract Mateen, and shot at him.[16][38][47][59][60] The breach drew Mateen out into the hallway, and at 5:14 a.m., he engaged the officers. He was shot eight times and killed in the resulting shootout, which involved at least eleven officers who fired about 150 bullets.[47][59][61][62][63] He was reported "down" at 5:17 a.m.[59]

At 5:05 a.m., the police said a bomb squad had set off a controlled explosion.[21][64] At 5:53 a.m., the Orlando police posted on Twitter, "Pulse Shooting: The shooter inside the club is dead."[21] Thirty hostages were freed during the police operation.[16][65] The survivors were searched by police for guns and explosives.[36]

Casualties

[edit]Forty nine people died in the incident, plus Mateen, and another 58 were injured, 53 by gunfire and five by other causes. Some survivors were critically injured.[1][17][66]

Fatalities

[edit]Thirty-nine, including Mateen, were pronounced dead at the scene, and eleven at local hospitals.[27][38] Of the thirty-eight victims to die at the scene, twenty died on the stage area and dance floor, nine in the nightclub's northern bathroom, four in the southern bathroom, three on the stage, one at the front lobby, and one out on a patio.[17][31] At least five of the dead were not killed during the initial volley of gunfire by Mateen, but during the hostage situation in the bathroom.[47]

Pulse was hosting a Latin Night; over 90% of the victims were of Hispanic background, and half of those were of Puerto Rican descent.[67][68] Four Dominican and three Mexican nationals were also among the dead.[69][70] An off-duty United States Army Reserve captain at the club who was not in uniform was also killed.[71][72]

The attack was the deadliest mass shooting by a single shooter in United States history, until the 2017 Las Vegas shooting[73][74][75][76][77] It is also the deadliest incident of violence against lesbian, gay, and bisexual people in the history of the United States—surpassing the 1973 UpStairs Lounge arson attack[78]—and the deadliest terrorist attack in the United States since the September 11 attacks in 2001.[27][79][80]

The names and ages of the victims killed were confirmed by the City of Orlando after their next of kin had been notified:[81][82]

- Stanley Almodovar III, 23

- Amanda Alvear, 25

- Oscar A. Aracena-Montero, 26

- Rodolfo Ayala-Ayala, 33

- Alejandro Barrios Martinez, 21

- Martin Benitez Torres, 33

- Antonio D. Brown, 30

- Darryl R. Burt II, 29

- Jonathan A. Camuy Vega, 24

- Angel L. Candelario-Padro, 28

- Simon A. Carrillo Fernandez, 31

- Juan Chavez-Martinez, 25

- Luis D. Conde, 39

- Cory J. Connell, 21

- Tevin E. Crosby, 25

- Franky J. Dejesus Velazquez, 50

- Deonka D. Drayton, 32

- Mercedez M. Flores, 26

- Peter O. Gonzalez-Cruz, 22

- Juan R. Guerrero, 22

- Paul T. Henry, 41

- Frank Hernandez, 27

- Miguel A. Honorato, 30

- Javier Jorge-Reyes, 40

- Jason B. Josaphat, 19

- Eddie J. Justice, 30

- Anthony L. Laureano Disla, 25

- Christopher A. Leinonen, 32

- Brenda L. Marquez McCool, 49

- Jean C. Mendez Perez, 35

- Akyra Monet Murray, 18

- Kimberly Morris, 37

- Jean C. Nieves Rodriguez, 27

- Luis O. Ocasio-Capo, 20

- Geraldo A. Ortiz-Jimenez, 25

- Eric Ivan Ortiz-Rivera, 36

- Joel Rayon Paniagua, 32

- Enrique L. Rios Jr., 25

- Juan P. Rivera Velazquez, 37

- Yilmary Rodriguez Solivan, 24

- Christopher J. Sanfeliz, 24

- Xavier Emmanuel Serrano Rosado, 35

- Gilberto Ramon Silva Menendez, 25

- Edward Sotomayor Jr., 34

- Shane E. Tomlinson, 33

- Leroy Valentin Fernandez, 25

- Luis S. Vielma, 22

- Luis Daniel Wilson-Leon, 37

- Jerald A. Wright, 31

Autopsies of the 49 dead were completed by the Orange County Medical Examiner's Office by June 14,[83] and their results were released in early August. According to the autopsy reports, many of the victims were shot multiple times in the front or side, and from a short distance. More than a third were shot in the head, and most had multiple bullet wounds and were likely shot more than 3 ft (0.91 m) away. In total, there were over 200 gunshot wounds.[84][85][86][87]

Injuries

[edit]Many of the injured underwent surgery.[88] Most of them—44 people—were taken to the Orlando Regional Medical Center (ORMC), the primary regional trauma center three blocks away; twelve others went to Florida Hospital Orlando.[83][89][90] Nine of ORMC's patients died there, and by June 14, 27 remained hospitalized, with six in critical condition.[91] ORMC performed surgeries on 76 patients.[92] The last of the injured was discharged from ORMC on September 6, nearly three months after the shooting.[91]

Three Colombians and two Canadians were among the injured.[93][94] Additionally, a responding SWAT officer received a minor head injury when a bullet hit his Kevlar helmet.[95]

Perpetrator

[edit]

The gunman was identified as 29-year-old Omar Mateen,[96] an American born in New Hyde Park, New York.[97][98] His parents were Afghans, and he was raised Muslim.[99] At the time of the shooting, he lived in an apartment complex in Fort Pierce, Florida, 117 mi (188 km) from the Pulse nightclub in Orlando.[100][101][102]

Mateen's body was buried in the Muslim Cemetery of South Florida, near Hialeah Gardens.[103]

Personal life

[edit]From October 2006 until April 2007, Mateen trained to be a prison guard for the Florida Department of Corrections. As a probationary employee, he received an "administrative termination (not involving misconduct)"[104] upon a warden's recommendation after Mateen joked about bringing a gun to school.[105] Mateen unsuccessfully pursued a career in law enforcement, failing to become a Florida state trooper in 2011 and to gain admission to a police academy in 2015.[104] According to a police academy classmate, Mateen threatened to shoot his classmates at a cookout in 2007 "after his hamburger touched pork" in violation of Islamic dietary laws.[106][107][108][109] Other witnesses said that they saw Mateen drink alcohol and even "get drunk."[110][111]

Since 2007, he had been a security guard for G4S Secure Solutions.[112][113] The company said two screenings—one conducted upon hiring and the other in 2013—had raised no red flags.[114] Mateen held an active statewide firearms license and an active security officer license,[115][116] had passed a psychological test, and had no criminal record.[117]

After the shooting, the psychologist who reportedly evaluated and cleared Mateen for his firearms license in 2007 by G4S records denied ever meeting him or having lived in Florida at the time, and said she had stopped her practice in Florida since January 2006. G4S admitted Mateen's form had a "clerical error" and clarified that he had instead been cleared by another psychologist from the same firm that bought the wrongly named doctor's practice. This doctor had not interviewed Mateen, but evaluated the results of a standard test used in the screening he undertook before being hired.[118] G4S was subsequently fined for lapses in its psychological testing program (see below).

In 2009, Mateen married his first wife, who left him after a few months; the couple's divorce became final in 2011. Following the nightclub attack, she said Mateen was "mentally unstable and mentally ill" and "obviously disturbed, deeply, and traumatized," was often physically abusive, and had a history of using steroids.[119][120][121][122] His autopsy revealed signs of long-term and habitual steroid use, so more toxicology tests were ordered for confirmation.[123] As of July 15, 2016, federal investigators were uncertain whether Mateen's steroid use was a factor in the attack.[124]

At the time of the shooting, Mateen was married to his second wife and had a young son.[125]

In September 2016, an imam for a mosque in Kissimmee released video footage showing what appeared to be Mateen on June 8, four days before the shooting, praying for about ten minutes. The imam said Mateen was praying there with his wife and child, and had no verbal exchanges with any of the other attendants. Though the FBI was already in possession of the mosque's security recordings, the video footage was released to the public only after a series of bombings or bombing attempts in New York and New Jersey, and a mass stabbing at a Minnesota shopping mall in September 2016.[126]

Motive

[edit]In the hours before the shooting, Mateen used several Facebook accounts to write posts vowing vengeance for American airstrikes in Iraq and Syria and to search for content related to terrorism. These posts, since deleted, were recovered and included in an open letter[127] by Senate Homeland Security Chairman Ron Johnson to Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg seeking further information about Mateen's use of the site.[128][129][130]

During the shooting, Mateen made a 911 call claiming it was an act of retaliation for the airstrike killing of, among others, IS militant Abu Waheeb in the previous month. He told the negotiator to tell America to stop the bombing.[50][131]

Despite numerous anonymous and named reports of LGBTQ connections,[132][133][134][135][136] the FBI was unable to verify any claims that Mateen was homosexual or frequented gay bars.[137] The FBI investigation found the witnesses claiming Mateen's homosexuality were mistaken or refused to go on the record, and doubts that Mateen was gay.[138][139] Law enforcement sources said the FBI found no photographs, text messages, smartphone apps, pornography, or cell tower location data to suggest Mateen lived a gay life, closeted or otherwise.[137][140]

On the day of the shooting, Mateen's father, Mir Seddique Mateen, said that he had seen his son get angry after seeing a gay couple kiss in front of his family at the Bayside Marketplace in Miami months prior to the shooting, which he suggested might have been a motivating factor.[18][141][142] Two days later, after his son's sexual orientation became a subject of speculation, Mateen's father said he did not believe his son was homosexual.[143] Mateen's ex-wife, however, claimed that his father called him gay while in her presence. Speaking on her behalf, her current fiancé said that she, his family, and others believed he was gay, and that "the FBI asked her not to tell this to the American media."[119]

During his wife's trial in March 2018, her defense revealed in a motion that Mateen had Googled "downtown Orlando nightclubs" and, after passing Disney Springs, traveled between Pulse and the Eve Orlando Nightclub before choosing to target Pulse. Cell phone records indicate that the final selection of the Pulse appears to have been made based on the lack of security – not because it was a gay club.[144] Trial witnesses said the decision to target Pulse was made at the last minute,[145] and the defense's motion argued that this "strongly suggests that the attack on Pulse was not a result of a prior plan to attack a gay nightclub."[146]

Aftermath

[edit]

Security-camera video footage was recovered from the nightclub as part of the investigation,[147] with a censored version later publicly released during the trial of Mateen's wife.[148] Facebook activated its "Safety Check" feature in the Orlando area following the shooting, allowing users to mark themselves as "safe" to notify family and friends—the first use of the feature in the United States.[149][150]

Following the shooting, many business venues in the United States, such as shopping malls, movie theaters, bars, and concert halls, reexamined their security procedures.[151][152] Also, police forces across the country announced plans to increase security at LGBT landmarks such as the Stonewall Inn and at Pride Month events including pride parades.[153]

Seddique Mateen released a Dari language video statement via Facebook on June 13 to speak about his son's actions.[154][155]

On the day of the attack, IS had released a statement via Amaq News Agency, taking responsibility for the attack.[156] On June 13, a broadcast from the Iraqi IS radio station al-Bayan said Mateen was "one of the soldiers of the caliphate in America," without indicating any foreknowledge of the shooting.[157]

On September 10, the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services fined G4S Secure Solutions $151,400 for providing inaccurate psychological testing information on more than 1,500 forms over a ten-year period, which allowed employees to carry firearms. Mateen's form was among those investigated.[158]

On November 4, it was reported that the Orlando Police Department was upgrading its equipment for officers following the shooting, since officers at the nightclub were not well-equipped for the event and therefore endangered. The upgraded equipment included ballistic helmets and heavier ballistic vests.[159]

Following the shooting and a vehicle-ramming attack and mass stabbing at Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio, a new federal initiative was launched, partially in response to at least one victim bleeding to death inside Pulse during the shooting. The initiative was designed to train people working at schools and other public places on how to treat injuries before paramedics arrive at the scene. Doctors have emphasized the importance for school faculty members to stay calm and assess injuries, but also discouraged the use of more invasive emergency procedures such as removing a bullet.[160]

Victim assistance efforts

[edit]The FBI's Office of Victim Assistance (OVA) provided "information, assistance services, and resources" to the victims and witnesses of the shooting that, depending on their case-by-case eligibility, may have consisted of "special funding to provide emergency assistance, crime victim compensation, and counseling."[161] The OVA, through its Victim Assistance Rapid Deployment Team and Crisis Response Canines, also provided help to responders of the shooting in the days following June 12.[162]

Immediately after the shooting, many people lined up to donate blood at local blood donation centers and bloodmobile locations when OneBlood, a regional blood donation agency, urged people to donate.[163][164] The surge in blood donations and the fact that the shooting targeted a gay nightclub spotlighted the Food and Drug Administration's controversial federal policy that forbids men who had sex with men in the past year from donating blood. Despite expressions of frustration and disapproval by a number of gay and bisexual men, and LGBT activists across the country and a group of Democratic lawmakers[165] urging the ban to be lifted, the FDA stated on June 14 that it had no plans to change the regulation and will reevaluate its policies "as new scientific information becomes available."[166][167][168]

A victims' assistance center, Orlando Family Assistance Center, was opened on June 15 inside Camping World Stadium by the City of Orlando.[169][170] During the eight days it was open, it provided help to 956 people from 298 families. Those remaining were then directed to the newly opened Orlando United Assistance Center jointly set up by the City and Orange County, which, according to the mayor of Orlando, "will stay open as long as there is a need."[171][172]

The two hospitals that treated Pulse victims, Orlando Regional Medical Center and Florida Hospital, announced in late August that they will not be billing the survivors or pursuing reimbursement.[173][174]

The City of Orlando offered free plots and funeral services at the city-owned Greenwood Cemetery for those killed in the shooting.[175][176][177]

Fundraising campaigns

[edit]Equality Florida, the state's largest LGBT rights group, started a fundraising page to aid the victims and their families, raising $767,000 in the first nine hours.[149][178][179] As of September 22, 2016, they have raised over $7.85 million online, a record for GoFundMe, with over 119,400 donors and an average of about $66 per donation.[180][181][182]

Another fundraising campaign, OneOrlando, was established by Mayor Buddy Dyer.[183] The Walt Disney Company and NBCUniversal, which operate the nearby Walt Disney World Resort and Universal Orlando Resort, respectively, each donated $1 million to the fund.[184][185] As of August 12, OneOrlando has raised $23 million,[186] with a draft proposal to start payouts starting September 27 on a rolling basis in which the highest compensations will go to the families of the 49 people killed, followed by the 50 victims who were physically injured and hospitalized for one night or more. OneOrlando's fund administrator said that the draft has not decided whether to pay people who were held hostage but were not injured, and will take public feedback in two 90-minute hearings to be held on August 4. A timeline of the draft proposal was released.[187][188] On August 11, its board of directors decided that the funds will only be dispersed to "the families of the dead, survivors who were hospitalized, survivors who sought outpatient medical treatment, and those who were present in the club when the shootings began but not physically injured," and that family members and survivors can start filing claims until the September 12 deadline.[186] As of December 1, OneOrlando paid out over $27.4 million to 299 recipients, according to officials, with six more claims worth an additional $2.1 million still being contested among family members of the slain victims.[189]

IDW Publishing and DC Entertainment created Love Is Love, a graphic novel sold to raise money for the victims. The novel became a New York Times best seller and more than $165,000 was raised. Through Equality Florida, the proceeds were donated to the OneOrlando Fund.[190]

Release of transcripts and videos

[edit]A total of 603 calls to 911 were made by victims, family members and friends of victims, bystanders, and rescue workers during the entire shooting.[191] On June 14, two dozen news agencies sent a four-page letter to Orlando's city attorney jointly demanding the release of recordings that 911 callers made on the night of the shooting. The letter also contained a request for scanner and dispatch recordings. The Orlando police refused to release the recordings, citing an "ongoing investigation."[192][193] June 20, the FBI released a transcript of the first call by the shooter and a summary of three calls with police negotiators.[54] On July 14, the University of Central Florida Police Department released nine body camera videos of UCFPD officers who rushed to Pulse to help Orlando police officers during the incident.[194]

On July 18, the City of Orlando released a detailed 71-page document of OPD officers' accounts and responses to the shooting. Requests to release recordings of 911 calls, police radio transmissions, and the exchanges between law enforcement and Mateen were denied, citing disagreements over whether they fall under local or federal jurisdiction. The status on the authority over the recordings is pending a court ruling.[195][196][197] On July 20, the Orange County Sheriff's Office (OCSO) released video footage from a body camera worn by one of its deputies during the incident.[198] On July 26, the Orange County Fire Rescue released a recording of a 911 call made during the shooting.[199] On July 29, the OCSO released dozens of pages of documents detailing the deputies' individual accounts of their involvement in the shooting.[200][201] On August 30, the OCSO released the 911 calls it received during the shooting.[202][203] Two days later, OPD and the city of Orlando released nine of their hundreds of 911 calls, which were all made by friends and relatives outside of Pulse during the incident; the rest are locked in a legal dispute between 24 media groups, OPD, and the city of Orlando.[204][205][206][207]

On September 14, the city of Orlando released 23 additional 911 calls made during the shooting.[208][209] These included calls made from rescue workers advising preparedness for dozens of victims,[191] a patron who escaped from Pulse with a friend who was shot, and the brother of a woman who was shot several times and trapped inside a bathroom in the nightclub.[210] On October 31, the City of Orlando released nearly 30 minutes of recordings of police negotiators talking with Mateen during the course of the shooting, after a judge with the Ninth Judicial Circuit Court of Florida ruled that these calls should be made public. A total of 232 other calls are still being withheld by the city.[211][212]

On November 10, the Orange County Sheriff's office released about two dozen videos of body camera footage of officers at the perimeter of the nightclub during the shooting. The footage, which was heavily censored, depicted officers conducting searches of bathrooms in the nightclub and tending to survivors.[213][214][215] On November 14, the City of Orlando released 36 police audio recordings made during the shooting, which record officers' attempts to contact Mateen, their remarks on his "serious, unruffled attitude," and their conversations about how to respond to the hostage situation.[216][217] Also released that day was an additional 911 call made by a woman who made it out of the nightclub with her sister, who was shot.[218] The next day, on November 15, 21 additional 911 calls were released.[46][219] This was followed by three additional hours of 911 calls released on November 16. In many of these calls, people trapped inside bathrooms, kitchens, and an upstairs office were questioning why police had yet to enter the nightclub.[46] Two days later, on November 18, 107 pages of transcripts of more than 30 911 calls were released. These calls were made during the first ten minutes of the shooting, and had to be released in the form of transcripts after a judge deemed them too graphic to be released as audio recordings. According to a city spokesman, all 911 calls made during the shooting have now been released to the public.[220][221][222]

Future of Pulse

[edit]

On September 14, 2016, the City of Orlando announced it would pay $4,518 to erect a new fence around the Pulse nightclub on September 19. The fence will feature a commemorative screen-wrap with local artwork that would serve as a memorial to the victims and survivors of the shooting.[223][224] It will also be smaller than the nightclub's previous fence, in order to allow for more efficient navigation by passers-by.[223]

On November 8 the City of Orlando announced its plans to purchase the Pulse nightclub later that month for $2.25 million and turn the site into a memorial for the victims and survivors of the shooting. The announcement was met with praise from Orlando's LGBT community.[225] However, the vote was postponed on November 15, with the city explaining that "more time was needed to plan a future memorial," and that there was some discomfort from city officials over having to pay such an amount of money. The vote was expected to be held on or before December 5.[226] In December 2016, the owner declined to sell the nightclub to the city due to emotional attachment.[227] The owner then created the onePULSE Foundation, and in May 2017, announced plans for a memorial site and museum originally slated to open in 2022.[228][229]

Investigations

[edit]Classification

[edit]

Officials have characterized the shooting as an act of terrorism. FBI Assistant Special Agent in Charge Ron Hopper[230] called the shooting a hate crime and an act of terrorism;[231] and Jerry Demings, a sheriff from the Orange County Sheriff's Office, classified it as domestic terrorism.[6] City of Orlando Chief of Police John W. Mina said Mateen seemed organized and well-prepared.[232] On March 13, 2018, the time of Mateen's wife's trial for aiding the attack, the FBI had still declined to classify it as a hate crime, and the prosecution said it had never contemplated arguing Mateen had targeted homosexuals.[233] They instead only (unsuccessfully) argued she provided material support to a foreign terrorist organization.[234]

On June 13, FBI Director James Comey told reporters, "So far, we see no indication that this was a plot directed from outside the United States and we see no indication that he was part of any kind of network." He said the United States Intelligence Community was "highly confident that this killer was radicalized at least in part through the Internet,"[235] and that the investigation had found "strong indications of radicalization by this killer and of potential inspiration by foreign terrorist organizations."[236] Several days after the shooting, the FBI announced on its website that it has become "the lead law enforcement agency responsible for investigating the shooting at Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida, on June 12, 2016."[161] The agency took the lead after the shooting was classified as a terrorist attack due to Mateen's pledge of allegiance to IS during the event.[62]

According to Senator Ron Johnson, Mateen searched online for references to the shooting during the attack, and made posts on Facebook expressing his support for Islamic State, saying "You kill innocent women and children by doing us [sic] airstrikes. Now taste the Islamic state vengeance."[237]

Weapons

[edit]Federal officials said a SIG Sauer MCX semi-automatic rifle and a 9mm Glock 17 semi-automatic pistol were recovered from Mateen's body, along with additional rounds.[13][238][239] Mateen had legally purchased the two guns used in the shooting from a shop in Port St. Lucie: the SIG Sauer MCX rifle on June 4 and the Glock 17 pistol on June 5.[9][240] He and law enforcement were reported to have fired over 200 rounds.[24][241][242] From his car, "hundreds of rounds" were found along with a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver; this gun was not used in the shooting.[62][239]

Previous FBI investigation of Mateen and cooperation with Seddique

[edit]Mateen became a person of interest to the FBI in May 2013 and July 2014. The 2013 investigation was opened after he made comments to coworkers about being a member of Hezbollah and having family connections in al-Qaeda,[243] and that he had ties to Nidal Hasan—perpetrator of the 2009 Fort Hood shooting—and Dzhokhar and Tamerlan Tsarnaev—perpetrators of the Boston Marathon bombing. According to new documents released on July 18, Mateen said that he made these comments in response to "a lot of harassment" and frequent derogatory epithets made by St. Lucie County Sheriff's deputies and his G4S coworkers, who taunted and made jokes about him being a possible Muslim extremist.[244][245] The comments resulted in his employer G4S removing Mateen from his post and the county sheriff reporting him to the FBI.[245][246] The documents also show him saying that he was "1000% American" and writing that he was against any "anti-American" and "anti-humanity" terrorist organizations.[244]

The 2014 investigation was opened after he was linked to Moner Mohammad Abu Salha,[99] an American radical who committed a suicide bombing in Syria. Mateen was interviewed three times in connection with the two investigations. Both cases were closed after finding nothing that warranted further investigation.[115][235][247] After the shooting, Director Comey said the FBI will review its work and methods used in the two investigations. When asked if anything could have or should have been done differently in regard to Mateen, or the FBI's intelligence and actions in relation to him, Comey replied, "So far, the honest answer is, 'I don't think so.'"[248]

A little over a month after the shooting, the FBI provided more details about its May 2013 to March 2014 investigation into Mateen, which was closed after a veteran FBI agent assigned to the case and his supervisor concluded that "there was just nothing there" and removed his name from the Terrorist Watchlist. Mateen was interviewed twice during the investigation, and had provided a written statement in which he confessed that he had previously lied to FBI investigators. During the investigation, the FBI had tracked his daily routine using unmarked vehicles, closely examined his phone records, and used two informants to secretly record his face-to-face conversations. The FBI Director said that they could have taken more initiative in gaining access to his social media accounts in 2013, but noted that back then such checks were not yet "part of [their] investigative DNA." However, it would not have mattered, as the analysis of Mateen's computer after the shooting showed that his social media accounts, including Facebook, had no ties to any terrorist groups, and that he did not post any "radical statements" until the early morning of the shooting. The FBI in 2013 also did not have the probable cause needed to obtain a search warrant in order to secretly listen to his phone calls or probe into Mateen's computer.[249]

On July 26, a Senate homeland security committee chairman sent a four-page letter to the inspector general of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) requesting an independent review of the FBI's 2013 and 2014 investigations. He wrote that if Mateen had stayed on the FBI watch-list, the federal agency would have been notified if he tried to purchase firearms, in which case "law enforcement potentially could have uncovered information on social media or elsewhere of Mateen's radicalization."[250]

On March 24, 2018, Sara Sweeney, the assistant attorney prosecuting Mateen's wife, Noor Salman, disclosed to her defense after the discovery period that her father-in-law, Seddique Mateen, was an FBI informant at various points between January 2005 and June 2016.[251] Agent Juvenal Martin, who handled the elder Mateen since 2006, said he considered making Omar an informant as well, after investigating and clearing him in 2013.[252][253]

Searches and possible accomplices

[edit]U.S. officials said Islamic State (IS) may have inspired Mateen without training, instructing, or having a direct connection with him.[157][254][255] Investigators have said no evidence linking Mateen to the group has emerged, and have cautioned that the shooting may have been IS-inspired without being IS-directed,[256] as was the case in the December 2, 2015, attack in San Bernardino, California.[23][257] Yoram Schweitzer of the Israeli Institute for National Security Studies suggested that Mateen associated the attack with IS to add to the notoriety of the incident, and said it was very unlikely that IS had known of him before the shooting.[157]

On June 16, Director of the Central Intelligence Agency John Brennan told the Senate Intelligence Committee that his agency was "unable to uncover any link" between Mateen and IS.[258]

Following the shooting, officers from multiple federal, state, and local law-enforcement agencies (including the FBI, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, Florida Department of Law Enforcement (FDLE), St. Lucie County Sheriff's Office, and Fort Pierce Police Department) converged on Mateen's home in Fort Pierce and another home in Port St. Lucie. A bomb squad checked Mateen's Fort Pierce home for explosives.[259] In June 2016, the House Intelligence Committee said that United States investigators "are searching for details about the Saudi Arabia trips Mateen made in 2011 and 2012."[260][261][262]

Senate Intelligence Committee member Angus King said that Mateen's second wife appears to have had "some knowledge of what was going on."[263][264] Media reports, citing anonymous law enforcement officials, said she was with Mateen as he scouted possible Orlando-area targets (including the Walt Disney World Resort's Disney Springs and the Pulse nightclub) and that she was also with him when he purchased ammunition and a holster in the months leading up to the attack.[265][266][267]

Trial and acquittal of shooter's wife

[edit]Mateen's second wife and widow, Noor Salman, was arrested in January 2017, at her home in Rodeo, California.[268] She was charged in federal court in Orlando with aiding and abetting as well as obstruction of justice.[269] Federal prosecutors accused her of knowing that Mateen was planning an attack.[270] Salman pleaded not guilty to the charges.[271] Salman moved to dismiss the obstruction charge; this motion was denied by U.S. District Judge Paul G. Byron.[272][273]

Salman's trial took place in March 2018.[274] During the trial, the prosecution revealed it withheld information during discovery that Salman's confession of helping scout potential attack locations was not true based on cell phone evidence, and that the FBI knew this even though it had been used to deny her bail.[253] The defense also sought to dismiss the charges or declare a mistrial on Brady disclosure grounds after this disclosure, and after the prosecution disclosed during the trial that Seddique Mateen had been a confidential FBI informant "at various points in time between January 2005 through June 2016."[275] The court denied Salman's motion to dismiss the charges or declare a mistrial.[252][274] On March 30 the jury acquitted Salman of both charges, although the jury foreman said "we were convinced she did know" about Mateen's plans for an attack of some sort in advance.[276][277]

FBI investigation

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2024) |

In July 2016, law enforcement officials reported that the FBI—after conducting "interviews and an examination of his computer and other electronic media"—had not found any evidence that Mateen targeted Pulse because the nightclub was a venue for gays or whether the attack was motivated by homophobia. According to witnesses, he did not make any homophobic comments during the shooting. Furthermore, nothing has been found confirming the speculation that he was gay and used gay dating apps; however, the FBI "has found evidence that Mateen was cheating on his wife with other women." Officials noted that "there is nothing to suggest that he attempted to cover up his tracks by deleting files." Generally, "a complete picture of what motivated Mateen remains murky and may never be known since he was killed in a shootout with police and did not leave a manifesto."[137] The FBI has yet to conclude its investigation As of 2016[update].[needs update][62][278]

Evaluations of performance of law enforcement

[edit]Two former SWAT members, one an active-shooter tactics expert and trainer, expressed misgivings about the three-hour delay in breaching the nightclub, citing the lesson learned from other mass shootings that officers can minimize casualties only by entering a shooting location expeditiously, even if it means putting themselves at great risk.[279]

At the request of John Mina, the Orlando chief of police, the U.S. Department of Justice's Office of Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) conducted a third-party "after-action assessment" of the Orlando Police Department's response to the shooting and its overall preparedness.[280][281] COPS commissioned the Police Foundation to prepare the report, which was released in December 2017. The report concluded that the Orlando Police Department response "was appropriate and consistent with national guidelines and best practices" and saved lives.[282] The report stated: "The initial tactical response was consistent with the OPD's active shooter training and recognized promising practices. However, as the incident became more complex and prolonged, transitioning from a barricaded suspect with hostages to an act of terrorism, the OPD's operational tactics and strategies were challenged by the increasing threat posed by the suspect's claim of improvised explosive devices inside the club and in vehicles surrounding the club."[282] The report authors noted that they lacked access to FBI reports and other data about the crime scene and shooter, and did not have information about "potential law enforcement friendly fire."[282]

In April 2017, the Orlando Sentinel obtained a copy of a 78-page presentation given by Mina to some ten police groups located around the world, which discussed the OPD's response to the attack and what it has learned. The presentation offered a comprehensive timeline of the attack and included diagrams and still photos from body camera footage showing officers in their initial confrontation with Mateen. According to the presentation, 500 interviews were conducted, 1,600 leads were followed up on, more than 950 pieces of evidence were collected, and more than 300 people were subpoenaed.[17]

In December 2016, the Florida Department of Law Enforcement completed a 35-page "after-action report" about its response to the nightclub during the shooting.[283][284] The report was publicly released in August 2017 after a public records request made by the Orlando Sentinel.[283][284] The report generally praised the FDLE's handling of the nightclub shootings, but detailed the agency's difficulties in notifying families and complications arising from its inter-agency policies, which led to them not immediately sharing information about the shooting with federal investigators.[283][284]

Reactions

[edit]

Florida Governor Rick Scott expressed support for all affected and said the state emergency operations center was monitoring the incident.[285] Scott declared a state of emergency for Orange County, Florida,[286] and Orlando mayor Buddy Dyer declared a state of emergency for the city.[287][288] On June 24, Scott directed that 49 state flags be flown for 49 days in front of the Florida Historic Capitol in Tallahassee, with the name, age, and photo of every victim displayed beneath each flag.[289]

The Obama administration expressed its condolences to the victims. President Barack Obama ordered that "the federal government provide any assistance necessary to pursue the investigation and support the community."[290] In a speech, he described the shooting as an "act of hate" and an "act of terror."[101][291][292] He also issued a proclamation on June 12 ordering United States flags upon non-private grounds and buildings around the country and abroad to be lowered to half-staff until sundown, June 16.[293] He and Vice President Joe Biden traveled to Orlando on June 16 to lay flowers at a memorial and visit the victims' families.[294]

Many American Muslims, including community leaders, swiftly condemned the shooting.[295][296] Prayer vigils for the victims were held at mosques across the country.[297][298][299] The Florida mosque where Mateen sometimes prayed issued a statement condemning the attack and offering condolences to the victims.[300] The Council on American–Islamic Relations called the attack "monstrous" and offered its condolences to the victims. CAIR Florida urged Muslims to donate blood even while observing the month of Ramadan—which requires Muslims to fast from dawn to dusk—and contribute funds in support of the victims' families.[295][301] Some Muslim groups called on members to break their Ramadan fast to be able to donate blood.[302]

The United Nations Security Council issued a statement condemning the shooting for "targeting persons as a result of their sexual orientation." It was supported by some countries that suppress homosexual behavior and discussion, such as Egypt and Russia.[303] Samantha Power, United States Ambassador to the UN, led a group of 17 UN ambassadors on a visit to the historic LGBT landmark Stonewall Inn to express their support for LGBT rights in response to the shooting.[304] Countries that released their own statements condemning the shooting include Afghanistan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Iran, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, and Turkey.[305]

Many people on social media and elsewhere, including 2016 United States presidential election candidates, members of Congress, other political figures, foreign leaders, and various celebrities, expressed their shock at the event and extended their condolences to those affected.[306][307] Vigils were held around the world to mourn those who were killed in the shooting, including one held at the banks of Lake Eola Park on June 19 that attracted 50,000 people.[308][309][310] Landmarks around the world, including the One World Trade Center and the Sydney Harbour Bridge, lit up in rainbow colors in remembrance of those killed in the shooting.[311]

On June 22, sixty House Democrats staged a sit-in at the US House of Representatives, in an attempt to force Speaker Paul Ryan, a Republican Party member, to allow votes on gun control legislation.[312] On June 23, Billboard magazine published an open letter addressed to the United States Congress demanding that universal background checks become federal law. The petition carried nearly 200 signatures of famous musicians and music industry executives. Joan Jett, Lady Gaga, Selena Gomez and many others were prominent signees of the document.[313][64] The House sit-in was unsuccessful in bringing gun control legislation to a vote.[312]

OnePulse Foundation, a charity organization created by a Pulse owner on July 7, filed documents with a plan to fund and build a memorial at the nightclub. The foundation is collaborating with the city of Orlando to determine the location of the memorial.[314][315][316] The non-profit organization also plans to start a fundraising campaign to provide financial help to the surviving victims who were injured and the families of the 49 who were killed.[317]

The LGBTQ gun rights organization Pink Pistols, with 36 chapters around the country, tripled both its membership (from 1,500 to 4,500), and its Facebook followers (to 7,000), in the week or so following the shooting.[318] As of June 24, 2016, it counted over 7,000 members.[319]

Google Search added a ribbon to its homepage, with the message "Our hearts are with the victims, their families, and the community of Orlando."[320]

In the aftermath of the 2018 trial, some media outlets re-assessed the reactions, possible motives, and media narrative of the shooting. They said that there was not evidence to say the shooting was motivated by anti-LGBT hate, though a Huffington Post piece acknowledged that Mateen very well may have been homophobic.[321][322]

See also

[edit]- Gun violence in the United States

- Gun law in the United States

- Gun politics in the United States

- 2016 United States House of Representatives sit-in

- Chris Murphy gun control filibuster

- Colorado Springs nightclub shooting (2022), a similar attack which targeted an LGBTQ nightclub

- LGBT in Islam

- List of Islamist terrorist attacks

- List of rampage killers (religious, political, or ethnic crimes)

- List of terrorist incidents in June 2016

- Terrorism in the United States

- Domestic terrorism in the United States

- Violence against LGBT people

- Our Happy Hours: LGBT Voices from the Gay Bars

- Mass shootings in the United States

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Rescue, Response, and Resilience: A Critical Incident Review of the Orlando Public Safety Response to the Attack on the Pulse Nightclub". December 17, 2017. Retrieved March 11, 2020 – via www.policefoundation.org.

- ^ Fitzsimons, Tim. "What really happened that night at Pulse". NBC News. NBC Universal. Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ Rothaus, Steve (June 12, 2016). "Pulse Orlando shooting scene a popular LGBT club where employees, patrons 'like family'". The Miami Herald. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ^ Tsukayama, Hayley; Berman, Mark; Markon, Jerry (June 13, 2016). "Gunman who killed 49 in Orlando nightclub had pledged allegiance to ISIS". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ^ Marr, Rhuaridh (June 15, 2016). "Drag Race star shares photo from Pulse, moments before shooting started". Metro Weekly. Jansi, LLC. Retrieved November 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Caplan, David; Hayden, Michael Edison (June 12, 2016). "At Least 50 Dead in Orlando Gay Club Shooting, Suspect Pledged Allegiance to ISIS, Officials Say". ABC News. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ a b Santora, Marc (June 12, 2016). "Last Call at Pulse Nightclub, and Then Shots Rang Out". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ "A timeline of what happened at the Orlando nightclub shooting". The Tampa Bay Times. June 12, 2016. Archived from the original on June 13, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ a b "Significance of Orlando gunman calling 911 during standoff". CBS News. June 13, 2016. Archived from the original on June 14, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ Zarroli, Jim (June 13, 2016). "Type Of Rifle Used In Orlando Is Popular With Hobbyists, Easy To Use". NPR. Archived from the original on June 13, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ^ Siemaszko, Corky (June 12, 2016). "AR-15 Style Rifle Used in Orlando Massacre Has Bloody Pedigree". NBC News. Archived from the original on June 13, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ^ Drabold, Will (June 13, 2016). "What to Know About the Gun Used in the Orlando Shooting". Time. Archived from the original on June 14, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ^ a b Jansen, Bart (June 15, 2016). "Weapons gunman used in Orlando shooting are high-capacity, common". USA Today. Archived from the original on June 18, 2016. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ^ "Orlando Mass Shooting: Mateen Was About To Kill More ... Chief Describes Final Assault". TMZ. June 13, 2016. Archived from the original on June 13, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ a b "Officer asked Pulse shooting victims: 'If you're alive, raise your hand'". ABC News. April 14, 2017. Archived from the original on April 14, 2017. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Mozingo, Joe; Pearce, Matt; Wilkinson, Tracy (June 13, 2016). "'An act of terror and an act of hate': The aftermath of America's worst mass shooting". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Hayes, Christal; Harris, David; Lotan, Gal Tziperman; Doornbos, Caitlin (April 13, 2017). "Exclusive: New Pulse review from Orlando police reveals details, lessons learned". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on April 13, 2017. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- ^ a b Grimson, Matthew; Wyllie, David; Fieldstadt, Elisha (June 12, 2016). "Orlando Nightclub Shooting: Mass Casualties After Gunman Opens Fire in Gay Club". NBC News. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Gibson, Andrew (May 31, 2017). "Orlando nightclub shooting timeline: Four hours of terror unfold". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- ^ "50 dead, Islamic terrorism tie eyed in Orlando gay bar shooting". CBS News. Associated Press. June 12, 2016. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Stapleton, AnneClaire; Ellis, Ralph (June 12, 2016). "Timeline of Orlando nightclub shooting". CNN. Archived from the original on June 13, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ a b Aisch, Gregor; Buchanan, Larry; Burgess, Joe; Fessenden, Ford; Keller, Josh; Lai, K.K. Rebecca; Mykhyalyshyn, Iaryna; Park, Haeyoun; Pearce, Adam; Parshina-Kottas, Yuliya; Peçanha, Sergio; Singhvi, Anjali; Watkins, Derek; Yourish, Karen (June 12, 2016). "What Happened Inside the Orlando Nightclub". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ a b Alvarez, Lizette; Pérez-Peña, Richard; Hauser, Christine (June 13, 2016). "Orlando Police Detail Battle to End Massacre at Gay Nightclub". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 13, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ a b Alexander, Harriet; Lawler, David (June 13, 2016). "'We thought it was part of the music': how the Pulse nightclub massacre unfolded in Orlando". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on June 13, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ Schogol, Jeff (June 14, 2016). "Marine vet's quick actions saved dozens of lives during Orlando nightclub shooting". Marine Corps Times. Archived from the original on August 18, 2016. Retrieved July 19, 2016.

- ^ Holley, Peter (June 15, 2016). "How a heroic Marine's military training helped him save dozens from Orlando gunman". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 9, 2016. Retrieved July 19, 2016.

- ^ a b c Fantz, Ashley; Karimi, Faith; McLaughlin, Eliott C. (June 12, 2016). "Orlando shooting: 49 killed, shooter pledged ISIS allegiance". CNN. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ "Pulse patron tried calming others during massacre new 911 calls reveal". CBS News. Associated Press. November 15, 2016. Archived from the original on November 17, 2016. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Goldman, Adam; Berman, Mark (August 1, 2016). "'They took too damn long': Inside the police response to the Orlando shooting". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 1, 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ^ a b Mohney, Gillian (June 14, 2016). "Hostage Injured at Orlando Nightclub Recounts Hours of Pain and Fear With Gunman". ABC News. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2016 – via Yahoo! News (GMA).

- ^ a b Katersky, Aaron; Withers, Scott; Kennedy, Scottye; Blake, Paul (April 14, 2017). "'If you're alive, raise your hand' desperate rescuer said in Pulse nightclub". ABC News. Archived from the original on April 14, 2017. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- ^ Hennessy-Fiske, Molly (June 14, 2016). "Survivor on Orlando gunman: 'He was not going to stop killing people until he was killed'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

[Patience Carter, a hostage] continued: 'There was an African American man in the stall with us... he said, 'Yes, there are about six or seven of us.' The gunman responded back to him saying that, 'You know, I don't have a problem with black people, this is about my country. You guys suffered enough.'

- ^ "Orlando shooting survivor recounts terrifying moments". Fox 29. June 13, 2016. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

'I could hear him talking, and he said, "I don't have a problem with black people. It's nothing personal. I'm just tired of your people killing my people in Iraq,"' Parker explained.

- ^ "Orlando survivor: Gunman tried to spare black people". CBS News. June 14, 2016. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

Carter, 20 years old, had fled into the bathroom of Pulse nightclub during the Orlando massacre, and as the situation was winding down, she said the gunman told police negotiators on the phone he pledged his allegiance to ISIS and wouldn't stop his assault until America stopped bombing his country.

- ^ Hennessy-Fiske, Molly (June 14, 2016). "Survivor on Orlando gunman: 'He was not going to stop killing people until he was killed'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ^ a b c Robles, Frances; Pérez-Peña, Richard (June 15, 2016). "Omar Mateen Told Police He'd Strap Bombs to Hostages, Orlando Mayor Says". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ^ Burch, Audra D.S. (July 2, 2016). "The paramedics of Pulse heard the gunfire, then saw something they never thought possible". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016. Retrieved July 19, 2016.

- ^ a b c Lotan, Gal Tziperman (June 12, 2016). "Orlando mass shooting: Timeline of events". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on June 13, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Barrett, Devlin; Entous, Adam; Cullison, Alan (June 12, 2016). "FBI Twice Probed Orlando Gunman". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on June 20, 2016. Retrieved June 21, 2016.

Law-enforcement officials said that investigation was prompted because Abu-Salha and Mateen attended the same mosque. Investigators concluded that while the two men probably knew each other's names and faces...

- ^ a b "FBI Boston Chief: In Call, Mateen Referred To Tsarnaevs As His 'Homeboys'". WBUR News. June 13, 2016. Archived from the original on June 14, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ^ Joscelyn, Thomas (June 20, 2016). "Orlando terrorist swore allegiance to Islamic State's Abu Bakr al Baghdadi". The Long War Journal. Archived from the original on June 25, 2016. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ Bertrand, Natasha; Engel, Pamela (June 13, 2016). "The FBI director just painted a bizarre picture of the man behind the worst mass shooting in US history". Business Insider. Archived from the original on June 14, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ Mazzetti, Mark; Lichtblau, Eric; Blinder, Alan (June 13, 2016). "Omar Mateen, Twice Scrutinized by F.B.I., Shows Threat of Lone Terrorists". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 16, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ Lotan, Gal Tziperman; Allen, Stephanie (June 28, 2016). "Dispatchers heard gunshots, screams, moans in Pulse 911 calls". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on June 29, 2016. Retrieved July 1, 2016.

- ^ a b Hauslohner, Abigail; McCrummen, Stephanie (June 21, 2016). "Orlando shooting: A quick response and then a long wait". The Washington Post. The Times-Picayune. Archived from the original on June 23, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ a b c Hayes, Christal (November 16, 2016). "Victims question rescue efforts in latest Pulse 911 calls". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on November 17, 2016. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Berman, Mark (April 14, 2017). "'If you're alive, raise your hand': Orlando police detail response to Pulse nightclub attack". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 14, 2017. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- ^ Fais, Scott (June 15, 2016). "Mateen to News 13 producer: 'I'm the shooter. It's me.'". News 13. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ^ Miller, Michael E. (June 15, 2016). "'I'm the shooter. It's me': Gunman called local TV station during attack, station says". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ^ a b Doornbos, Caitlin (September 23, 2016). "Transcripts of 911 calls reveal Pulse shooter's terrorist motives". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on September 26, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

Mateen referred to a U.S.-led air strike on May 6 that killed Abu Wahib, an ISIS military commander in Iraq, and three other jihadists, according to the Pentagon. 'That's what triggered it, OK?' Mateen said. 'They should have not bombed and killed Abu [Wahib].'

- ^ a b c d "Records: Gunshots, moaning heard by dispatchers as terror unfolded in Pulse". WFTV 9 ABC. July 1, 2016. Archived from the original on July 2, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ Liston, Barbara (June 12, 2016). "Fifty people killed in massacre at Florida gay nightclub: police". Reuters. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ "50 Dead, 53 Hurt In Orlando Nightclub Shooting". CBS Local Minnesota. Associated Press. June 12, 2016. Archived from the original on June 13, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f "Investigative Update Regarding Pulse Nightclub Shooting" (Press release). Tampa, Florida: Federal Bureau of Investigation. Tampa Division. June 20, 2016. Archived from the original on June 20, 2016. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ^ Yan, Holly; Brown, Pamela; Perez, Evan (June 16, 2016). "Orlando shooter texted wife during attack, source says". CNN. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ^ Mohyeldin, Ayman; Williams, Pete; Helsel, Phil (June 17, 2016). "Orlando Gunman Omar Mateen and Wife Exchanged Texts During Rampage". NBC News. Archived from the original on July 17, 2016. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- ^ Smith, David (June 15, 2016). "Omar Mateen's wife may be charged if she knew he was planning Orlando shooting". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ^ "Orlando survivor: Gunman tried to spare black people". CBS News. June 14, 2016. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ^ a b c Doornbos, Caitlin (August 5, 2016). "Autopsy: Pulse shooter Omar Mateen shot eight times". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on August 6, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ^ Sarkissian, Arek (June 14, 2016). "Officers may have shot Orlando club patrons". KARE 11. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ^ "Orlando gay nightclub shooting 'an act of terror and hate'". BBC News. June 12, 2016. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Harris, David (July 13, 2016). "Official: FDLE to wrap up Pulse shooting investigation within month". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on July 15, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ^ Sickles, Jason (August 5, 2016). "Pulse nightclub shooter Omar Mateen shot eight times, autopsy reveals". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on August 6, 2016. Retrieved August 5, 2016.

- ^ a b Solis, Steph; Bacon, John (June 12, 2016). "Islamic State linked to worst mass shooting in U.S. history". USA Today. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016. Cite error: The named reference "USAToday" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Lyons, Kate (June 12, 2016). "Orlando Pulse club attack: gunman identified as police investigate motive". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Stolberg, Sheryl Gay; Pérez-Peña, Richard (June 14, 2016). "Orlando Shooting Survivors Cope With the Trauma of Good Fortune". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 14, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

The slaughter early Sunday left 49 victims dead, in addition to the gunman, and 53 wounded ... More than 30 of the wounded remained in hospitals on Tuesday, including at least six who were in critical condition.

- ^ Golshan, Tara; Nelson, Libby (June 13, 2016). "Pulse gay nightclub shooting in Orlando: what we know". Vox. Archived from the original on June 13, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ Sullivan, Kevin; Hernández, Arelis R. "Orlando's Latino community hit hard by massacre at nightclub". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 14, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ Cabral, Ariel (June 16, 2016). "Identifican a un cuarto dominicano muerto en atentados Orlando" [A fourth Dominican was killed in Orlando attacks] (in Spanish). Hoy. Archived from the original on July 4, 2016. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

- ^ Hays, Chris (June 13, 2016). "Consulate eager to help Mexican nationals killed in Orlando nightclub shooting". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ^ "Orlando Casualties Include Army Reserve Captain". Department of Defense News. Defense Media Activity. June 14, 2016. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ^ Kevin, Lilley (June 16, 2016). "Will Reserve captain killed in Orlando massacre earn Purple Heart?". Army Times. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

Capt. Antonio D. Brown wasn't on duty or in uniform when he was shot dead early Sunday morning...

- ^ "The deadliest shootings in U.S. history". Fox News. October 2, 2017. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ "Las Vegas shooting now tops list of worst mass shootings in U.S. history". USA TODAY. October 2, 2017. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ Ingraham, Christopher (June 12, 2016). "In the modern history of mass shootings in America, Orlando is the deadliest". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 1, 2018.

- ^ Peralta, Eyder (June 13, 2016). "Putting 'Deadliest Mass Shooting In U.S. History' Into Some Historical Context". NPR. Archived from the original on October 22, 2017.

- ^ Nelson, Laura J. (June 14, 2016). "The worst mass shooting? A look back at massacres in U.S. history". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016.

- ^ Stack, Liam (June 13, 2016). "Before Orlando Shooting, an Anti-Gay Massacre in New Orleans Was Largely Forgotten". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 14, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

The terrorist attack ... was the largest mass killing of gay people in American history, but before Sunday that grim distinction was held by a largely forgotten arson at a New Orleans bar in 1973 that killed 32 people at a time of pernicious anti-gay stigma.

- ^ "Obama: Orlando An Act Of 'Terror And Hate'". Sky News. June 12, 2016. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Swanson, Ann (June 12, 2016). "The Orlando attack could transform the picture of post-9/11 terrorism in America". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ "Victims' Names". City of Orlando. June 12, 2016. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Teague, Matthew; McCarthy, Ciara; Puglis, Nicole (June 13, 2016). "Orlando attack victims: the lives cut short in America's deadliest shooting". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ^ a b Miller, Naseem S. (June 15, 2016). "Orlando shooting autopsies complete, more survivors discharged". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016.

- ^ Hayes, Christal (August 5, 2016). "Pulse families get some answers from autopsies". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on August 6, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ^ Harris, David (August 8, 2016). "Final autopsies of Pulse victims released". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on August 9, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2016.

- ^ Toppo, Greg (August 8, 2016). "Autopsies: victims of Pulse nightclub shooting shot more than 200 times total". USA Today. Archived from the original on August 9, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2016.

- ^ Schneider, Mike (August 9, 2016). "Autopsies: A third of Pulse nightclub victims shot in head". Yahoo! News. The Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 10, 2016. Retrieved August 10, 2016.

- ^ "Orlando shooting victims arrived by 'truckloads,' doctor says". Chicago Tribune. June 14, 2016. Archived from the original on June 14, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ^ Alvarez, Lizette; Pérez-Peña, Richard (June 12, 2016). "Orlando Gunman Attacks Gay Nightclub, Leaving 50 Dead". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Domonoske, Camila (August 25, 2016). "Orlando Hospitals Say They Won't Bill Victims Of Pulse Nightclub Shooting". NPR. Archived from the original on September 5, 2016. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ a b Miller, Naseem S. (September 6, 2016). "Last hospitalized Pulse shooting survivor discharged after nearly 3 months". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on September 7, 2016. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ Jacobo, Julia (September 6, 2016). "Last Orlando Shooting Survivor Discharged From Hospital". ABC News. Archived from the original on September 7, 2016. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ Alsema, Adriaan (June 14, 2016). "Three Colombians injured in Orlando nightclub shooting". Colombia Reports. Archived from the original on October 4, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ^ "Two Canadians injured in Orlando shooting fear for their lives". Montreal Gazette. June 15, 2016. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ^ "Photo released shows injury to officer who was shot in head, but protected by helmet". WFTV 9 ABC. Cox Media Group. June 29, 2016. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017.

- ^ "Orlando gunman identified as Omar Mateen". BNO News. June 12, 2016. Archived from the original on June 13, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Lotan, Gal Tziperman; Brinkmann, Paul; Stutzman, Rene (June 13, 2016). "Gunman Omar Mateen visited gay nightclub a dozen times before shooting, witness says". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on June 13, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ Brady, Ryan (June 13, 2016). "Orlando shooter born in New Hyde Park". Queens Chronicle. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ a b Blinder, Alan; Healy, Jack; Oppel, Richard A. Jr. (June 12, 2016). "Omar Mateen: From Early Promise to F.B.I. Surveillance". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 13, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ "50 killed in shooting at Orlando nightclub, Mayor says". FOX News Channel. June 12, 2016. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ a b Young, Lou (June 12, 2016). "ISIS Claims Responsibility For Orlando Nightclub Attack That Left 50 Dead". CBS New York. Associated Press. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Jones, Elliott (June 12, 2016). "Omar Mateen's connections to Fort Pierce, Port St. Lucie". Treasure Coast Newspapers. Archived from the original on June 13, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Allen, Stephanie; Pesantes, Erika (June 23, 2016). "Pulse shooter Omar Mateen buried near Miami, records show". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on August 19, 2016. Retrieved August 10, 2016.

- ^ a b Swisher, Skyler (June 16, 2016). "Omar Mateen failed multiple times to start career in law enforcement, state records show". Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on June 20, 2016.

- ^ Felton, Ryan; Laughland, Oliver (June 18, 2016). "Orlando shooter was fired for making a gun joke days after Virginia Tech killings". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 18, 2016. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ^ Berzon, Alexandra; Emshwiller, John R. (June 17, 2016). "Orlando Shooter Was Dismissed From Academy Over Gun Inquiry, State Says". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on June 18, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

Susanne Coburn Laforest, a 61-year-old retired corrections officer and former classmate of Mateen, said he threatened to shoot his classmates at a cookout—which she said was held on a gun range—after his hamburger touched pork, in violation of Muslim laws.