1st Maine Cavalry Regiment

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. When this tag was added, its readable prose size was 23,000 words. (June 2023) |

| Maine U.S. Volunteer Cavalry Regiments 1861-1865 | ||||

|

The 1st Maine Cavalry Regiment was a volunteer United States cavalry unit from Maine used during the American Civil War.

Service history

[edit]The regiment was organized in Augusta, Maine, on October 31, 1861, and served for three years. The original members were detached from the regiment on September 15, 1864, when their service was up, and mustered out back in Portland on November 25. Later recruits, along with the Maine men of the 1st District of Columbia Cavalry (men recruited in the Augusta, Maine[2] area between January and March 1864 and consolidated into seven companies) and those who chose to reenlist, were retained in the regiment. The regiment was split into three battalions of four companies each. One battalion was made up of former 1st District men and the other two were a mix of 1st Maine veterans and DC men. These three battalions continued until the regiment's mustering out at Petersburg, Virginia, on August 1, 1865.[3]

Initial organization in 1861

[edit]Maine had responded to Lincoln and Congress's April 25, 1861, call for ten regiments of infantry of which eight had been organized and left the state by the end of August.[4] That month the federal government had put out a call to Maine for five more regiments of infantry, six batteries of light artillery, a company of sharpshooters, and a regiment of cavalry to serve three years.[5][note 1]

This cavalry regiment was intentionally raised at large from all counties of Maine and organized into twelve companies.[6][note 2] The regiment's staff consisted of a colonel (COL), lieutenant colonel (LTC), three majors (MAJ), a first (1LT) or second lieutenant (2LT) as adjutant (1LT), surgeon, assistant surgeon, chaplain, regimental quartermaster, regimental commissary of subsistence, and three first (1LT) or second lieutenants (2LT) serving as battalion quartermasters.[7][note 3] The regiment rated a sergeant major (SMAJ), a sergeant (SGT) as a chief bugler, a veterinary surgeon, a regimental quartermaster sergeant (QMSGT), regimental commissary sergeant (CSGT), hospital steward, saddler sergeant, sergeant farrier, and an ordnance sergeant. A captain (CAPT) commanded each company in the 1st Maine with a first lieutenant and a second lieutenant commanding the two platoons. The company commander also had the aid of a company first sergeant (1SGT) a company quartermaster sergeant, a company commissary sergeant, a farrier, and a sergeant (SGT) acting as the company commander's orderly. Each lieutenant in the platoon had two sergeants, four corporals (CPL), a bugler, and 39 privates (PVT). This gave each company a paper strength of 100 men.[8][note 4]

The regiment had high standards for its recruits and the quality of its mounts.[9] Recruiters were to enlist "none but sound, able-bodied men in all respects, between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five years of correct morals and temperate habits, active, intelligent, vigorous, and hardy, weighing not less than one hundred and twenty-five or more than one hundred and sixty pounds"[10] While the average United States Infantryman was 26 and 5′ 8.25″ tall and 155 pounds, the average United States Cavalryman was the same age but slightly shorter at 5′ 7″ and lighter at 145 pounds[11]). It encamped at Augusta at the State Fairground, renamed Camp Penobscot, where recruits initially learned military discipline and drill. Horses would arrive in December.

The 1st Maine Volunteer Cavalry Regiment mustered into federal service at Augusta on November 5, 1861, as a three-year volunteer cavalry regiment.[12] It was commanded by COL John Goddard from Cape Elizabeth. A Regular Army cavalry officer, LTC Thomas Hight, was the second-in-command. Another regular, CAPT Benjamin F Tucker served as the Adjutant with the rest of the field and staff officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs) being Maine men. In the companies, apart from the Company H commander, CAPT George J. Summat and the 1st Lieutenant in Company L, 1LT Constantine Taylor, all the company officers and NCOs were Maine volunteers.

The 1st Maine had an advantage in recruiting over the infantry and artillery. Many recruits found the idea of riding rather than walking incredibly attractive. Also, the cavalry had an air of glamor and romance that the other branches did not have:[13]

- There hung about the cavalry service a dash and an excitement which attracted those men who had read and remembered the glorious achievements of 'Light Horse Harry' and his brigade, and of 'Morgan's Men' in the revolutionary war, or who had devoured the story of 'Charles O'Malley,' and similar works. In short, men who had read much in history or in fiction, preferred the cavalry service.[14][note 5]

It is unclear whether the 1st Maine received either the 1854 cavalry shell jacket or 1857 sack coat or both. The army did issue all ranks the same standard sky-blue double-breasted winter overcoat with attached cape and a rubberized poncho for rainwear.[15] They also received the special sky-blue wool cavalry trousers with the reinforcing double layer in the seat and inside leg due to the expected extended time in the saddle.[16]

Training, deployment, and operations in 1862

[edit]There were prejudices against the cavalry in the War Department as it was originally thought it would not be of much use during the expected short period of conflict.[17][note 6] MGEN George McClellan felt that it took a minimum of two years to professionally train volunteer cavalry and that they would have nothing to do but be couriers and pickets.[18] There was also the added factor that the cost to equip and mount a Union cavalry regiment in 1861 was between $500,000 and $600,000, or roughly twice that of an infantry regiment.[19] Some of the leadership in the command understood the lack of faith:

- The men of the south were born horsemen, almost. Old and young were nearly or quite as much at home on horseback as on foot, and the horses, also, were used to the saddle. Therefore, they could put cavalry regiments into the field with great facility and in comparatively good fighting condition, as witness the famous Black Horse Cavalry. In the northern and eastern states, it was different. Equestrianism was almost one of the lost arts. Few, especially in cities, were accustomed to riding, and the great majority of men who would enlist in the cavalry must learn to ride and to use arms on horseback, as well as learn drill, discipline, camp duties, and the duties of service generally. "A sailor on horseback," is a synonym for all that is awkward, but the veriest Jack tar on horseback was no more awkward than was a large proportion of the men who entered the cavalry service in the north and east.[20]

While the federal government figured out where to send the regiment, they continued training at the camp living in army issue camp tents through a cold winter. The recruits were soon finding the reality of cavalry life to be quite different from their preconceived notions.[21] The command stressed the importance of caring for their mounts and had a stable built before the first horses arrived. The necessary caring for their means of mobility, their mounts, made the men's days busier and longer than the infantryman's. During the cold, in which the regiment lost 200 men to disease and injuries, the men noted that their horses "had quarters that winter more comfortable than did the men, in comparison with the usual accommodations for man and beast."[22]

When Edwin Stanton replaced the disgraced Simon Cameron as Secretary of War, the 1st Maine narrowly avoided disbandment before they even saw service.[23] They were saved by the intervention of an officer who was impressed by their enthusiasm and rapid learning.[24] As training continued, the men and horses gradually meshed into a cohesive unit overcoming the fact that many horses had no prior experience with being ridden and some of the men had no prior experience riding.[25][note 7]

COL John Goddard, a lumberman, was disliked by the regiment because he was a strict disciplinarian and a rigid moralist,[26][note 8] but many of the regiment's veterans later credited his hard hand with making them soldiers.[10] However, he was disliked by almost all such that some officers went to Augusta threatening to resign if he was not removed.[27] Governor Washburn wanted no problems, so COL Goddard resigned his commission on March 1, 1862. MAJ Samuel H. Allen was commissioned Colonel by the governor and took command. To replace him, CAPT Warren L. Whitney of Company A was promoted to Major. In turn, 1LT Sidney W. Thaxter was made Captain and new Company A commander. Due to being passed over in favor of Allen, LTC Hight resigned and returned to command his company, in the 4th U.S. Cavalry.[28] At that time, the regiment was organized into three battalions: 1st Battalion (under MAJ Warren L. Whitney with companies A, D, E and F), 2nd Battalion (under MAJ Calvin S. Douty with companies B, I, H and M), and 3rd Battalion (under MAJ David P. Stowell with companies C, G, K and L).[12]

Still without weapons, the 1st Maine's training was drawn from the experience and training of the regular army personnel assigned to the regiment and concentrated on getting the men and their horses to work efficiently as a team in the various formations called for by cavalry regulations. The officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs) read and studied their copies of two manuals, McClellan's Regulations and Instructions for the Field Service of the United States Cavalry in Time of War and Cooke's, Cavalry Tactics, or, Regulations for the instruction, formations, and movements of the cavalry of the army and volunteers of the United States (both published in 1861 at the start of the conflict).[29] Through these manuals and the guidance of the regulars, the Maine troopers learned the various formations for travel and combat, the basics of setting up pickets and vedettes, and the various bugle calls to command and coordinate all these activities.

Dismounted drill was of secondary importance, but it was not forgotten. The lack of sabers was part of the shortage that plagued the U.S. volunteer cavalry organizations during the first year of the war led to "some ludicrous improvisations."[30] The 1st Maine's solution was to buy wooden laths:

- Some time during the winter laths were procured, for the purpose of learning and practicing the sabre exercise. These were made into swords of the most grotesque shape by the men, and the exercise was looked upon very generally as a farce, was 1aughed at by outsiders, and was discontinued after a very short time; yet there is no doubt that the rudiments of the use of the sabre learned with the aid of those wooden swords was never forgotten, and proved to be of advantage when the real sabre was put into the hands of the· men. No arms were furnished, except a few old muskets for use on guard duty, till the regiment arrived at Washington.[31]

Departure for Washington and the front

[edit]Finally, in March the regiment was ordered to the front in Virginia. 1st Battalion left for Washington on Friday, March 14, 1862, under command of COL Allen, arriving on Wednesday, the 19th without COL Allen who had fallen sick and was hospitalized in New York City.[32] Delayed by a late winter snowstorm, 2nd Battalion departed Augusta on Thursday, March 20, under MAJ. Douty, arriving on Monday, the 24th. On that day, 3rd Battalion under MAJ Stowell left and pulled into DC on the 28th.The battalions all entrained in box cars in Augusta, eight horses and men per box car, and rode to New York city via Portland, Boston, and Providence. After a ferry across the Hudson, the detachments had a more comfortable transit to Washington with the horses in the box cars, but the men in passenger cars.[33]

As each company in the regiment detrained and reported at the Washington Depot or New Jersey Avenue Station, each trooper received his official government arms issue of a Model 1860 Light Cavalry Saber and a pair of Colt Model 1860 revolver.[34][note 9] The regiment also received an issue of ten breech-loaded Sharps Carbines per company, however, by now, a number of the regiment's men had privately purchased breech-loaded Sharps, Burnsides, Smith, and Merrill carbines in Maine before departure or from one of the merchants along the rail route, to give themselves a weapon with a greater range. This meant that the 1st Maine had a slightly higher proportion of carbines than the average U.S. Volunteer cavalry regiment.[35][note 10] In Washington, the regiment pitched their tents with other reinforcements on Capitol Hill on the 29th.[36] In camp, the regiment immediately began grinding and sharpening their newly issued blades.[37]

On Sunday, March 30, the regiment received orders to send five companies to Harper's Ferry and join the Federal troops providing security for the Baltimore & Ohio's link between Washington and the Ohio Valley. On that day, the line had reopened, and the War Department wanted to guard it against rebel raids. MAJ Douty took five companies with the largest number of carbines[38] and organized them into a new 1st Battalion. The remainder of the regiment would stay in Washington awaiting the return of COL Allen.[12] The regiment, "five months after its organization, was at Washington, armed and equipped, and a portion of it under marching orders."[37]

The 1st Battalion, comprising companies A, B, E, H, and M, loaded on box cars Monday, March 31 for Harper's Ferry, by way of Frederick and joined the " Railroad Brigade" commanded by COL Dixon Stansbury Miles, which guarded the important logistical route. The battalion's companies were separated and assigned to duty at different points along the railroad.

The remainder of the regiment remained in Washington DC. They spent the days after the 1st Battalion's departure honing their sabers and "in drill, mounted and dismounted, and in the manual of arms, and in generally preparing for active service."[39]

The Shenandoah, the "Middletown Disaster," and First Winchester

[edit]To win the war, the United States needed to defeat the Confederate armies in the field. To win the war, the rebels had to break the will of the Federals to fight. The Shenandoah Valley, between the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Appalachians, figured in both of those war aims and ergo its control was strategically important. Known as the breadbasket of the Confederacy, the Shenandoah Valley provided a route for rebel attacks into Maryland, Washington, and Pennsylvania, thereby cutting the link between Washington and the midwest[40][note 11] — directly attacking the United States' will to fight. The valley "was rich in grain, cattle, sheep, hogs, and fruit and was in such a prosperous condition that the Rebel army could march itself down and up it, billeting on the inhabitants."[41] which meant that Yankee control of the valley would weaken the rebel armies helping to defeat them. Because of its strategic importance it was the scene of three major campaigns. The valley, especially in the lower northern section, was also the scene of bitter partisan fighting as the region's inhabitants were deeply divided over loyalties, and Confederate partisan John Mosby and his Rangers frequently operated in the area. Due its strategic importance, the valley saw an ebb and flow between the contesting armies until the last autumn of the war.

Transport of goods from the valley to the east was done via a network of macadamized pikes/turnpikes and rail between the larger towns supported by numerous smaller dirt roads and canals knitting them further. Much of this system had been put in place by Virginia Board of Public Works (VBPW) under the guidance of Claudius Crozet. The main north–south road transportation was the Valley Turnpike,[42][note 12] a public-private venture through the VBPW running 68 miles (109 km) from Martinsburg up through Winchester, Harrisonburg, and ending at Staunton.[42] There were several other macadamized roads running between the larger towns and railroads. Three rail lines were the main east–west routes with B&O in the lower valley, Manassas Gap in the middle/upper, and the Virginia Central in the upper, southern end all connecting to the Valley Pike. The B&O met it at Martinsburg, the Manassas Gap met it at Strasburg after passing through the Blue Ridge Mountains at Manassas Gap at Front Royal, and the Virginia Central met it at Staunton after coming through the mountains in Crozet's Blue Ridge Tunnel.

Rebels under Jackson had severed the B&O at the northern end of the lower Shenandoah Valley during the late spring and summer of the prior year.[43] Repeated raids and operations by Jackson's cavalry subordinate Turner Ashby and his the 7th Virginia Cavalry ("Ashby's Brigade"[44][note 13]) damaged so much railway infrastructure that it took over ten months to reopen the line on March 30, 1862. The paved roads were a great asset to the rebels in the valley being unaffected by inclement weather.[45] An official report described Martinsburg as "on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, at the northern terminus of the Valley Pike—a broad macadamized road, running up the valley, through Winchester, and terminating at Staunton."[41] Besides being a node between road and rail, Martinsburg was also home to the large, important B&O maintenance shop and roundhouse.

For the United States, the Maine men in the five companies were vital to keeping the B&O open. The battalion (and the rest of the regiment that remained in D.C.) would have an eventful Spring in 1862 marked by participation in operations against Jackson in the Shenandoah Campaign.

The Railroad Brigade

[edit]MAJ Douty and his five companies arrived in Harper's Ferry and were immediately posted to key facilities along the line.[46] CAPT George M. Brown's Company M remained in Harper's Ferry. The rest were loaded aboard the B&O and sent to their posts. MAJ Douty and CAPT Sidney W. Thaxter's Company A were the first stop and offloaded at the B&O maintenance shop in Martinsburg.[47] CAPT Black Hawk Putnam's Company E was the next to detrain at Back Creek where the B&O crossed it before flowing past Allensville and emptying into the Potomac.[48][note 14] Company H commanded by CAPT George J. Summat was dropped off along the rail line opposite Hancock, MD. CAPT Jonathan B. Cilley and Company B was furthest west and last off at the Berkely Springs resort.[49][50][note 15]

As well as scouting and patrolling along the rail beds, the companies patrolled out from their bases along several of the macadamized pikes. In this period along the important artery, the men of the 1st Battalion learned their craft well gaining valuable experience in the saddle.[51] There were a handful of skirmishes, and the men of the 1st Maine captured some rebel prisoners during this period, successfully defending the line and keeping it open. On April 14, MAJ Douty received a promotion to Lieutenant Colonel of the regiment.[52] During their time on this duty, the men of this battalion began to learn what a valuable source the local black population, enslaved and free, was for intelligence as well as who and where the local Unionists were.[53] Of note the men in Company A were greatly pleased to be in Martinsburg where the overwhelming majority of Unionists caused the rebels to call it "Little Massachusetts".[54]

Joining Banks

[edit]Throughout April and May, Banks and his Department of the Shenandoah had been receiving direct tasking from Secretary of War Stanton on coordinating with MGEN John C. Fremont's Mountain Department and MGEN McDowell's Department of the Rappahannock. This had led to stripping of assets from Banks and changing orders between joining with one of the other departments. As April rolled into May, Banks continued to receive frequent directives daily from the War Department over the telegraph. This revolution in communications hindered Banks in that it kept him on a tether of sorts inhibiting his freedom of action.

On Friday, May 9, 1862, the 1st Battalion came together from the various company posts to Martinsburg and went up the valley (south) to join MGEN Nathaniel P. Banks' forces at Strasburg. They joined BGEN John P. Hatch's cavalry brigade. By May 13, the men of the 1st Maine found that Banks had divided his force to an extent that he only had 6,500 men with him astride the Valley Pike in Strasburg and 2,500 in Front Royal, fifteen miles east-southeast on the east side of the valley. On that day, BGEN Shields had departed from Front Royal on the Manassas Gap Railroad to go east and join McDowell's department. The small garrison (COL John Kenly, his Union 1st Maryland Infantry, and Companies B and D of 5th New York Cavalry[55]) at the Front Royal station was to prevent rebel movement along the Manassas Gap rail line. Hatch's brigade covered the approaches to Strasburg with Hatch encamped at Middletown.[56] On May 20, Douty was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel.[57]

At the point in the valley where Banks had advanced, the Manassas Gap rail met another macadamized road, Winchester-Front Royal Pike, that ran eighteen miles along the eastern side of the valley and met Valley Pike at Winchester, 25 miles southwest of Harper's Ferry. Valley Pike passed seven miles over Cedar Creek down to Middletown, three miles further to Newtown (present day Stephens City), and finally seven miles into Winchester where it met the Winchester-Front Royal road. Several dirt roads ran between these to paved roads on either side of the valley.[58] The men of LTCOL Douty's battalion go to know the lay of the land during their patrols in the upper Shenandoah Valley in the next couple of weeks. They learned who the Unionists were and where the back roads went.[59]

Soon, Banks started getting intelligence from the local Unionists and black population that MGEN Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's corps of 17,000 men, fresh from whipping MGEN John C. Frémont's at McDowell was heading his way. Banks had been stripped of men and artillery so that his force of 23,000 at the beginning of May to 9,000 by the 21st.[60] Since Jackson was now positioned to block him from joining with Fremont, Banks began wondering if his now reduced force around Strasburg and Front Royal, fifteen miles east-southeast on the east side of the valley, would be able to resist any contact with Jackson. On May 23, Banks received reports of Jackson attacking the garrison at Front Royal before the telegraph link was severed.[61] He fired off telegrams to Stanton keeping the Secretary updated on intelligence on the Front Royal attack until early morning when he decided his outnumbered force's best option was to begin withdrawing to Winchester taking the Valley Turnpike so that he could take as much of his supply train with him.[62] By 03:00, on May 24 the twelve-mile-long column of Banks' wagons began to roll north down the Valley Turnpike to Winchester.

Jackson advances

[edit]By 07:00 on May 24, 1862, a Saturday, MGEN Banks at Strasburg wired Secretary Stanton when he confirmed that Jackson's 17,000 had completely routed the garrison at Front Royal "with considerable loss in killed, wounded, and prisoners."[63] and were closing on him, turning his position. Under these circumstances, Banks figured that if he could reach Winchester, he would preserve his lines of communication and increase the odds of reinforcement before contact.[64] At dawn, Banks called Hatch forward from Middletown and had him push patrols to Woodstock and along Manassas Gap Railroad. He also tasked Hatch to round up any stragglers and put to torch any supplies of military value that could not be carried off.[65] He then began his retreat north along the Valley Pike. Doughty's battalion and two companies of the 1st Vermont under MAJ William D. Collins,[66][note 16] just returned from patrol toward Woodstock at 02:00, (all told, a force of around 400 men) had temporarily camped at historic Belle Grove plantation[67][note 17] Banks pulled them onto the road at 07:00 as a rear guard escort up the road to Middletown. Banks was anxious and wanted to know where the rebels were. He sent two companies of the 29th Pennsylvania Infantry and elements of the 1st Michigan Cavalry to head east on Chapel Road, a country lane which connected Middletown, four miles north, with Cedarville (modern North Front Royal) the site of Kenly's surrender, in turn, four miles north of Front Royal.[68]

The 1st Battalion and the two companies took up position in the rear guard of the column as Banks' column set out on the road to Winchester. As the column passed through Middletown, Banks still had not heard from the 29th Pennsylvania and 1st Michigan. In "one of the smartest moves he made all day,"[68] Banks erred on the side of caution, sent messengers to LTC Douty, then waiting for the rear of the column at Toms Brook, to come up to headquarters with his command.[69][56] The five companies of the 1st Battalion under LTC Douty and the squadron of the 1st Vermont were sent north to Newtown to turn east down Chapel Road until they met, identified, and observed any Rebels. The 1st Battalion's duties were the normal cavalry tasks "to ascertain if the enemy was in force in that vicinity, to gain all possible information of his movements, and report often. If [they] met the enemy advancing [they were] told to hold him in check if possible."[70] Feeling a bit more secure, at 09:00, Banks ordered the 500-wagon train to begin the 20-mile trek to Winchester.[69][note 18]

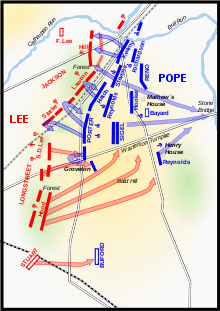

Unknown to the 1st Battalion, they were about to meet Jackson's plan to trap Banks between Strasburg and Newtown on the Valley Turnpike.[71] Jackson and Richard S. Ewell had spent the night at Cedarville and were up before dawn with his army ready to move. Still ignorant of Banks' precise location, Jackson had Ewell out on the Front Royal-Winchester Turnpike by 06:00. Jackson sent BGEN George Hume Steuart, in command of the 2nd and 6th Virginia Cavalry, ahead of the infantry to three miles north of Nineveh and cut west, off the roads and cross country to Newtown on the Valley Pike between Middletown and Winchester "to observe the movements of the enemy at that point."[72] At the same time, he directed COL Turner Ashby and his 7th Virginia to send two companies east along the rail line from Front Royal to watch his rear, and three companies west along the rail line to scout the Federals in Strasburg. The remainder of the 7th would scout to the west of the Font Royal-Winchester pike and screen Jackson's infantry.[73][note 19]

Initial contact

[edit]

Stuart's force reached Newtown and found the road crowded with the lead portion of Banks' wagon train. Steuart charged the United States forces, captured prisoners, spread panic. While his troopers scattered the teamsters (which included many formerly enslaved local black resident who had good reason to avoid recapture,[74] they did not burn the wagons which would have trapped the rest of Banks' train.[75] They advanced south along the pike and met the main body of Banks' army a mile south of Newtown where they were driven off by infantry.[76] Steuart reported his contact back to Jackson.

During the breakfast halt at Nineveh,[77] Trimble drew Jackson's attention to a column of smoke coming from the direction of Strasburg.[78] Receiving Steuart's report and opting to intercept Banks at Middletown, Jackson retraced his route to Cedarville. Ewell's division with the 1st Maryland Infantry, and supporting artillery, were to advance from Cedarville up Front Royal Pike to turn at Nineveh and be ready for Jackson's order to advance on Newton and meet Steuart.[79] Meanwhile, COL Turner Ashby and BGEN Richard Taylor with his and BGEN Isaac Trimble's brigades were to advance west to Middletown on the dirt Chapel Road, made muddy by a morning rain shower, with his men from the 7th Virginia and probe across the fields toward Strasburg, followed by the rest of the army.[75] The slogging through the mud was laborious and none of the Confederate columns knew what to expect to their front.[80] This force would be coming right at the Maine and Vermont cavalry troopers.[81]

Two miles short of the Front Royal Pike (three-quarters of a mile short of Molly Camel Run),[56] at 09:00, Ashby's scouts had observed an earlier patrol of the 29th Pennsylvania Infantry and 1st Michigan Cavalry who had not seen them.[80] This force had only advanced three mile toward Cedarville when they received a few carbine shots from Ashby's men. Instead of ascertaining who they had met, they retreated hastily to Middletown. A local Unionist who was on Banks' staff, David Hunter Strother, later wrote that they had failed through timidity and incompetence thereby blinding Banks to his true situation.[82][note 20]

Ashby's scouts likewise failed in their mission to report the contact back to Jackson and moved scross the fields to the west along Molly Camel Run toward the a column of smoke at Strasburg and failed to scout further up the road to Middletown. Since he was still ignorant of what lay ahead on the Chapel Road, Jackson had sent his cartographer, MAJ Jedediah Hotchkiss with a small cavalry squad scouting further up Chapel Road toward Middletown[80] while sending word for Ashby to turn his aim from Stasburg to Newtown.[69] Hotchkiss was under instruction to send reports back every half hour. He had only moved one and a half miles and was beginning an ascent up a rise Chapel Road just beyond Molly Camel Run when Douty's videttes posted along the road saw Hotchkiss's party coming along the muddy track.[83] While remaining unobserved,[84] the videttes sent a rider back to warn Douty of an approaching scouting party. Douty moved forward and threw out skirmishers to right and left of the road and sent the men armed with carbines ahead as skirmishers into the woods along the road. He sent riders back to the signal officer in Middletown for relay to Hatch and Banks.[85] He then waited as the enemy closed range with his men.

As Hotchkiss and his men came into range of pistols and carbines, the Maine and Vermont troopers drove them back with heavy fire, and the Confederates retreated out of sight.[86] Douty consulted with Collins and both realized that the woods would prevent them from seeing any flanking movements by the rebels from their position. at 11:00, having seen no more sign of the rebels, Douty called in his skirmish line and left out vedettes in the road and in the fields to keep watch. At the advice of MAJ Collins,[66] he pulled the rest of his small command two miles back toward Middletown to Providence Church (present-day Reliance United Methodist Church) where they were able to see the fields for miles on either side of the road.

Hotchkiss had sent a rider back to report contact to Jackson who again, sent word to Ashby to change direction from Strasburg to Chapel Road.[87]

At 12:00, the vedettes came up the road and rejoined with word that Rebel cavalry and infantry were following them. Within fifteen minutes, Hotchkiss, and his party with two companies of the 8th Louisiana Infantry appeared, halted, and kept out of carbine range.[85] In the ensuing half-hour, the rebels brought up artillery and unlimbered them in the road.

Around 12:45, the rebel artillery opened on Douty and his men and the infantry and dismounted cavalry advanced. Holding fire until the regrouped, reinforced rebels came into range, Douty's men kept up a heavy fire that threw back the enemy,[81] particularly the 21st North Carolina Infantry from Taylor's Brigade. This led Hotchkiss to believe he was facing a much larger force of infantry in the woods as well as Douty's cavalry astride the road.[66] This managed to buy Banks more time as Jackson sent word to Ewell's Division to halt until he knew against whom he was fighting.[88]

In response, rebel artillery continued firing on the 1st Maine and the now empty woods. This led Douty to bring in his skirmishers and make fighting withdrawal. "stubbornly for every inch of ground"[89] back to Middletown. As they withdrew, the rebels pushed forward. He executed a steady and deliberate withdrawal the four miles back along Chapel Road to Middletown, causing enough uncertainty in Jackson's mind that it delayed the advance by nearly two hours. Under the pressure of the advance, Douty got his command back to Middleton with the loss of a horse. At 14:30 Douty turned off the Chapel Road and onto Church Street a block east of Valley Turnpike.[88] The signal officer on duty told him that Banks had already through and BGEN Hatch was expected at any moment. Douty led his men into the village of Middletown, south of the crossroads, to wait for Hatch.

The 8th Louisiana now appeared north of town and the accompanying guns of Chew's Battery from Steuart's Brigade began shelling Douty's and Collins' men. Douty was about to call for a withdrawal back to Strasburg when Hatch arrived[85] around 15:30.[81] He deployed Douty and Collins into the side streets and fields east of the turnpike, and waited for 5th New York and the remainder of the 1st Vermont to catch up from burning the last of the stores at Strasburg.

At the same time, Ashby's men appeared on the high ground on their flank to the southeast of town. Despite the macadam, travel along the shoulders had thrown up a great cloud of dust all along the pike.[90] Within minutes, 8th Louisiana Infantry had moved down from the high ground, cut the pike, and began plundering the wagon train while Chew's artillery began firing on wagons further north.[91] Hatch kept Douty's command in a skirmish line to the east between Jackson's Corps and the town. The 1st Battalion and the Vermonters kept the 1st Virginia and 21st North Carolina Infantry at bay.[92]

At 16:00, Hatch realized his command was surrounded when messengers sent to contact Banks' retreating wagon train returned with news that the Valley Pike was blocked by wagons and manned by rebels. Hatch said to LTC Douty, "We must cut our way through."[93] This was the seed of the 1st Maine's "Middletown Disaster".

"The Disaster"

[edit]Hatch had the 1st Maryland Cavalry and 5th New York Cavalry with him as well as Douty's small command. COL Charles H Tompkins and the remaining ten companies of the 1st Vermont Cavalry and future Medal of Honor winner Charles H. T. Collis and his independent company of Pennsylvania Zouaves d'Afrique (manning wagons) were still en route from Strasburg. He sent riders back to warn Tompkins and Collis to skirt to the west of Middletown and take back roads to Winchester since the rebels held the Valley Turnpike.[94]

As rebel artillery continued to sporadically fire shells into downtown Middletown, Hatch formed up his brigade along the turnpike by the town square in columns of fours. The 1st Battalion and the 1st Vermont fell in at the rear of the brigade's column at the southern edge of Middletown.[89] Taking the lead, Hatch moved out on the turnpike. Already receiving sporadic rifle fire before going very far, Hatch took the column off the pike onto a dirt road a half-mile out of town.[89][note 21]

Upon contact with the enemy on this road, Hatch charged and the whole column galloped down the road shooting and slashing at any rebels in their path. This generated a cloud of dust that obscured the turn off the Valley Turnpike.[95] At the head of the column as the charge continued, Hatch saw that Ashby had managed to get one of his batteries behind a wagon barricade back on the turnpike and supported it with elements of the 21st North Carolina.[71] Seeing more rebels moving off the pike and cutting a dirt lane parallel to the pike by several hundred yards, Hatch continued west on his path and smashed through the handful of Ashby's cavalry on that road, bypassing the artillery.[92]

Looking back over the fields, the column could see the two companies of the 1st Vermont followed by the Maine battalion continuing in a charge down the Valley Turnpike. Unfortunately for the 1st Battalion, the huge cloud of dust had obscured the column departing the macadam from MAJ Collins. The rebels had seen them, as well, and a quick-thinking officer on Jackson's staff, LT Douglas quickly rushed a company of infantry to a stonewall in a blocking position over the Turnpike.[96] LTC Douty had been at the rear seeing to a severely wounded CAPT Cilley of Company B when he noticed the Vermont companies moving out at the trot.[94] When MAJ Collins and two 1st Vermont companies missed the turn and came out of the dust cloud, they saw a rebel battery supported by an infantry blocking the Valley Turnpike. With the stone walls alongside the road leaving no other option, at point-blank range, they charged:[97]

- Moving at a rapid rate in sections of four, in a cloud of dust, supposing they wore following their General, coming suddenly upon this battery in a narrow road where it was impossible to maneuver, a terrible scene of confusion followed. Those at the head of the column wore suddenly stopped, those in the roar unable to restrain their horses rushed upon each other, and men and horses were thrown in a confused heap. And as they wore all the while exposed to the shot, and shell, and bayonets, of the enemy, it is not strange that their loss was severe, numbering one hundred and seventy men with an equal number of horses. At the same time companies A and B at a little distance were under a severe fire, during which [Captain] Putnam, and Lieutenant Estes were wounded.

Escaping from this perilous position, Lieut. Colonel Douty fell back on the pike, and taking an intersecting road and making a detour to the left. After a hard march rejoined the main column at Newtown [sic, actually Winchester] the next day, and was immediately ordered to support a battery.[98]

- Moving at a rapid rate in sections of four, in a cloud of dust, supposing they wore following their General, coming suddenly upon this battery in a narrow road where it was impossible to maneuver, a terrible scene of confusion followed. Those at the head of the column wore suddenly stopped, those in the roar unable to restrain their horses rushed upon each other, and men and horses were thrown in a confused heap. And as they wore all the while exposed to the shot, and shell, and bayonets, of the enemy, it is not strange that their loss was severe, numbering one hundred and seventy men with an equal number of horses. At the same time companies A and B at a little distance were under a severe fire, during which [Captain] Putnam, and Lieutenant Estes were wounded.

As the column had moved out, Douty had mounted his horse and rode toward the head of the Vermont companies to join Collins. Before passing the last company, the column had already broken into a gallop and "was charging up the pike amid a shower of shell and bullets."[94] He found the dust so thick that he could see nothing but what was close by him. He began seeing men and horses strewn on the wayside. By the time he reached the third company from the end, Company M, the bodies of horses and men, alive and dead, were contained so tightly that they could not continue, and men started retreating.[99][note 22] The battalion spilled over the stonewalls and into the surrounding fields cutting their way through the rebels. Many Maine men were unhorsed by the collision with those ahead of them as well as by rebel artillery and musketry.[100] Many these were taken prisoner by Wheat's "Louisiana Tigers" in Taylor's Brigade. Many took off on foot to try to escape. Luckily for those who were able to put some distance between themselves and the enemy, the presence of abandoned wagons from Banks' train loaded with supplies provided a welcome distraction as more and more of Trimble's and Taylor's men left the firing line to rifle through it.[101] This gave Douty and his men the chance to escape.[102] The woods surrounding the fields were noticeably absent of any underbrush that could hide the escaping troopers as they darted between the trunks of the oak trees. While Ashby's cavalry were able to capture some more of the dismounted men, the Maine horseman found that by using pistols and sabers in small groups, they were able to fend off their pursuers who eventually ceased pursuit to join the infantry in the plundering the abandoned wagons.[103]

Douty gathered what men he could and pulled back into Middletown. He reformed his command in the center of town. A company of Ewell's infantry formed up at the southern end of town and opened fire on the New England cavalrymen.[104] LTCOL Douty pulled his men back out of their range and turned left down the side-streets and rode west out of Middletown out of sight of the rebels.[94] Eventually, he turned his group north the Middle Road and found Hatch and the brigade after a two-mile gallop.[105]

Battle of First Winchester

[edit]The rest of Hatch's brigade who had seen the debacle across the fields had continued parallel to the Valley Turnpike but found that every time they tried to regain the pike and join Banks, their way was blocked by Ewell's troops.[94] They ended up cutting through Ashby's cavalry and rejoined Banks at Newtown. There Hatch found Col George Henry Gordon and his brigade with five companies of the 1st Michigan Cavalry giving ground slowly. Hatch's men joined in the rear-guard action making Winchester at 22:00, Saturday evening.

At dawn on Sunday, May 25, BGEN Charles Winder's Stonewall Brigade occupied the hill due south of the town. As Winder attacked down toward Winchester, Banks' artillery soon found their range and began an effective, punishing fire. The 1st Battalion was ordered to provide support for one of these batteries.[106] The Stonewall Brigade stalled in their attack. Jackson ordered Taylor's Brigade to outflank the Union right which they did with a strong charge pushing the right flank back into town. At the same time, Ewell's men got around the extreme left of the Union line. With the impending double envelopment, around 07:00, Banks' line pulled back through the streets of town. The 1st Battalion covered the battery as they limbered up and headed north on the Valley Pike.

As the U.S. troops pulled out of the town, the Maine troopers noted that the local secessionist civilians were jeering them, throwing boiling water, and even shooting at them.[107] Along with the rest of Hatch's brigade, they found themselves fighting their way out of the town under attack from all sides. The vehemence of the local secessionists and Jackson's force climaxed in reports several instances of no quarter being given to some of Banks' wounded who had fallen out of the retreat.[108]

Instead of a wild flight, Jackson later wrote that Banks's troops "preserved their organization remarkably well" through the town. Elated, Jackson rode cheering after the retreating enemy shouting "Go back and tell the whole army to press forward to the Potomac!"[109] Luckily for the 1st Battalion in the rearguard, the Confederate pursuit was ineffective. Ashby and the rest of the rebel cavalrymen had conducted vigorous pursuits of U.S. forces to the south and east. By the time they rejoined Jackson, their horses were blown and men too exhausted to effectively chase down Banks' rearguard leading Jackson to write, "Never was there such a chance for cavalry. Oh that my cavalry was in place!"[110]

As Hatch's brigade swept back and forth at the rear to keep the occasional pursuer at arm's length[111] the outnumbered Federals fled relatively unimpeded for 35 miles in 14 hours, crossing the Potomac River into Williamsport, Maryland after dark around 21:00, Sunday evening. Hatch noted the fine performance of the 1st Maine Cavalry in his post action reports.[94] Among the units in Banks' retreating force for whom the 1st Maine provided a sense of security were their fellow Mainer, the 10th Maine.[112] Union casualties were 2,019 (62 killed, 243 wounded, and 1,714 missing or captured),[71] Confederate losses were 400 (68 killed, 329 wounded, and 3 missing).[113][note 23]

Aftermath

[edit]First Winchester had proven costly to the 1st Maine. Several the companies in the 1st Battalion suffered more than half their number as prisoners after the mess in the road with the rebel battery. Company A suffered the most, arriving at Winchester with eighteen men. During this action, the battalion lost three killed, one mortally wounded, nine wounded, twelve wounded and taken prisoner, one mortally wounded and taken prisoner, forty-nine taken prisoner of whom five would die in rebel captivity, and 176 horses and equipment.[114][94]

Over the next three weeks, many men who had eluded capture or had escaped captivity straggled in to rejoin the regiment.[115] On Tuesday, forty odd men arrived with COL DeForest of the 5th New York Cavalry with thirty-two wagons of supplies that they had managed to spirit away from Confederate hands at Middletown, having been forced by rebel pursuers to cut through the mountains and ford the Potomac upriver by Clear Spring.[116] Some stragglers arrived on foot having lost their mounts in the fighting. A group of twenty had been held in Winchester when they encountered MAJ Whitney and his small command en route to MGEN Banks on June 3.[117] Additionally, thirty or more of the men being transported south on the Valley Turnpike to captivity in Richmond managed to escape the night of the May 24 and make their way back to the 1st Maine in Maryland.[118] A group of fourteen troopers from Companies A and L managed to report back in to the regiment at Westport on May 27 after escaping through the mountains via Pughtown and Bath.[119][note 24][120] Several members of the command made their way to Harper's Ferry and thence to the regiment at Williamsport.[121][122]

All the while, starting with the first letters home, there was much confusion regarding the dead, wounded, and missing. CAPT Cilley was mistakenly reported dead in several letters.[123][124] This confusion was unfortunately common during the war.[125]

In Williamsport, while Douty worked diligently remounting his command,[126] the news of Banks's ouster from the Valley caused a stir in Washington lest Jackson continue north and threaten the capital. Lincoln, who in the absence of a general in chief[127][note 25] was exercising day to day strategic control over his armies in the field, took aggressive action in response. He planned trap on Jackson using three armies. Frémont's would move to Harrisonburg on Jackson's supply line, Banks would move back in the Valley, and 20,000 men under McDowell would move to Front Royal and attack Jackson driving him against Frémont at Harrisonburg.

Unfortunately, this plan was complex and required synchronized movements by separate commands. Banks declared his army was too shaken to move. It would remain north of the Potomac until June 10. Frémont and McDowell bungled it completely. Jackson defeated the two in detail – Frémont at the Battle of Cross Keys on June 8 and McDowell at Battle of Port Republic on June 9. Of note, one of the 1st Maine's nemeses, Turner Ashby died on Chestnut Ridge near Harrisonburg in a skirmish with Frémont's cavalry.[128]

On June 12, the 1st Battalion crossed the Potomac and returned to Winchester. Company K continued down the Valley Pike to Strasburg. Companies E and M traveled south on the also macadam Front Royal-Winchester Road to Front Royal,[129] where they were joined on the 20th by companies A and B, and the brigade[32][note 26] placed attached to BGEN Crawford's infantry brigade.[130][note 27] The remainder of LTC Douty's command's time in the Shenandoah was uneventful save a brief skirmish at Milford, on July 2 (CAPT Thaxter commanding). On July 9, Douty received orders to rejoin the regiment at Warrenton.

In the Department of the Rappahannock

[edit]The main body of the regiment had remained in Washington, DC while the 1st Battalion operated in and around the Shenandoah Valley. On April 2, 1862, orders arrived for a march to Warrenton, VA on Friday, April 4. The troopers spent Thursday sharpening their sabers and checking their equipment. When their departure was delayed by a day, the regiment continued honing their edged weapons. On Friday evening, the men were given a patriotic send-off including a concert sung by ladies from Maine who were residing in Washington.[131]

At midday Saturday, the regiment departed their encampment on Capitol Hill led by MAJ Stowell (COL Allen was still recuperating in New York). The inexperienced regiment "accompanied by a baggage train long enough for a whole corps later in the war,"[132] rode down Maryland Avenue SW and crossed the Potomac on Long Bridge.[32]

Into rebel territory

[edit]On the Virginia side, it checked in at Fort Runyon.[133][note 28] At the fort, they received orders to report to BGEN McDowell's Department of the Rappahannock's[132] forces at Warrenton Junction (present day Calverton, Virginia) via the Columbia, Little River, and Warrenton Turnpikes. The regiment crossed the Alexandria Canal and climbed up the Columbia Turnpike passing Fort Albany[134][note 29] on the left as they crested the rise. The regiment continued on and could see Robert E Lee's home, Arlington House on a rise to the right. The men of the 1st Maine were taking in the sights as they traveled for the first time in rebel territory.

The first impressions of Virginia were not very favorable. The roads were muddy and in bad order, and houses were few, far between, not particularly good, even before the war, and now presenting a dilapidated, tumble-clown appearance. The whole country wore a deserted, unhealthy look, to which the earthworks, abandoned camp-grounds, and the waste and destruction which accompany an army, even when not in active operation, added an extra gloom.

Here the men saw for the first time the desolating effects of war. On their line of march to and from this point nearly every house,was deserted of its owners. Its doors and its windows and the fences that enclosed it, and the birds that sang and the flowers that bloomed around it, all were gone. The music of singing birds and the sweeter music of children's voices had ceased ... The pleasant dwellings had been left desolate, and no cheerful salutations of neighbors and no ringing laugh of youthful glee was heard. Instead of these the streets resounded with the roll of the drum, the stern word of command and the heavy tramp of armed men

Samuel H. Merrill, Chaplain, 1st Maine Cavalry[136]

As Lee's home faded into the distance, the men descended a small vale to Arlington Mills Station crossing both 4 Mile Run and the Alexandria, Loudoun, and Hampshire Railroad (AL&H).[137][note 31] The men noted heavy use of the railway as they crossed it seeing other troops and supplies at the station.[138][note 32] A mile beyond the railway and above the dell, at 15:00, the regiment briefly stopped at Bailey's Crossroads to water their horses. They had taken three hours to travel the nine miles from the encampment on Capitol Hill to the crossroads.[139] Once the horses were watered, the regiment mounted up and continued down Columbia Turnpike. At Padgett's Tavern, the regiment turned right on the Little River Turnpike another macadamized road. They crossed the unfinished new rail cut that would run from the Orange and Alexandria Railroad through Annandale and Fairfax to Haymarket. By sunset on Saturday, April 5, 1862, the 1st Maine had reached Fairfax Courthouse.[140]

The men in the regiment were familiar with the history of the courthouse "where the eloquence of a Patrick Henry and a ·William ·Wirt bad exerted its magic power.[141][note 33]" While dismayed at its state of ruin, the troopers still were fascinated by the building, the grounds, and the various remnants of the county records strewn about the location. Picketing the horses in the Courthouse's yards, the troopers were crammed into the Courthouse's various buildings.[142]

The regiment was up at dawn on Sunday morning, April 6. By 09:00, they had groomed their horses, broke fast, and were on the Little River Turnpike once more heading west. A mile down the pike, the command made a left turn in the village of Germantown and rode onto the Warrenton Turnpike heading west-southwest where Centreville, VA lay six miles away. They continued passing vacant fields on either side of the road. Ahead on a slight ridge on either side of the pike, the men saw some of the rebel "Quaker guns," manned with stuffed dummies that the rebels had placed there to give their pickets on the rise the look of a fortified position from the distance. At noon they passed them and entered Centreville. A water halt was made there for the horses, and after seeing to their mounts, the men inspected the effigies with great interest.[143] Within an hour, the command had remounted and left Warrenton Pike and turned onto a dirt road heading south to Manassas Junction. Shortly, they found themselves crossing Bull Run over a partially rebuilt bridge which had been destroyed by the Confederates when they retreated. Although on the edge of the battlefield, the Maine men saw solitary chimneys where houses used to be. Dead rotting horses generated "that peculiar stench which afterwards became familiar to all soldiers."[143] As the march continued, many a Maine trooper was sobered by the sight of numerous soldiers' graves on the roadside along Warrenton Turnpike.[144] At dark the regiment was at Manassas Junction. Their horses were picketed by the side of the road and the men had their first experience (of many) in sleeping out-of-doors. The weather was fair, and morale was high, and the "boys, though tired, were in good spirits, and inclined to make the best of the circumstances.[143] The command had marched 17 miles from Fairfax Courthouse.

Monday, April 7, 1862, was a gray, drizzly day, as the 1st Maine traveled along the dirt road that paralleled the Orange & Alexandria past Bristoe Station and Catlett's Station all the way to Warrenton Junction. They saw ripe wheat fields and fine manors, all abandoned. It started drizzling in the late morning, and after a midday water stop, the rain increased. The muddy road and numerous fords over creeks made the march a difficult one, but after twelve miles, around 15:00 they reported to McDowell's Department of the Rappahannock in Warrenton Junction.[145] The baggage train were still on the dirt road having been held up at a ford that was too deep for their transit.

Training and patrolling

[edit]After scrounging for rations the first day in camp, the wagons finally caught up with the regiment having taught the men a valuable lesson – always have some rations and extra ammunition on their person or mount.[146] Graced with an early spring snowstorm on Tuesday, the men made the best of camp life, drilling, and seeing to their horses.[147]

First assigned to Gen. Abercrombie's brigade, and soon afterwards to Gen. Ord's division within McDowell's department, the 1st Maine was learning its job. The occasional patrols were the primary means for this on-the-job-training. Companies were detached singly, in twos, threes, and more to conduct these reconnaissances. Friday, April 11, they spent the night scouting Warrenton and returned Saturday morning. They made several more such patrols through the remainder of April and into May.[148] In this time, they became adept at river-crossings, bringing the right amount of gear for a mission, and handling their horses while also learning how valuable a source of intelligence both the enslaved and free black population would be.[149]

On Tuesday, April 15, Company C under CAPT Dyer made a patrol down the Orange & Alexandria to the Rappahannock where they saw black slaves building earthworks on the opposite side of the river north of the railroad. As they moved north, they could see a large, white plantation house which they surmised to be the rebel headquarters. Two slaves who had escaped across the river estimated that there were between 5,000 and 7,000 troops total in the area. Examination of the field works through binoculars led Dyer to believe they alone could hold 3,000–4,000 men. As they turned to report back, three rebel batteries opened fire on them.[150] After getting out of range and sight of the rebels, they learned from some black women the identities of several locals who were visiting their camp and reporting back to the rebels.

The next evening, Wednesday, April 16, LTC Willard Sayles, commander of the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry, took a squadron of his regiment and Companies D and F of the 1st Maine on a patrol toward Liberty Church to interrogate and arrest the reported rebel informants.[151] After receiving accurate intelligence from the suspects' slaves, three men were arrested and turned over to the brigade headquarters.

On Tuesday, April 22, COL Allen rejoined his command. The regiment was being moved around and attached to various infantry brigades. Sometimes various companies were detached for provost or courier duties. Other than these command duties their time was spent on picket duty and scouting patrols for their various attached commands. Their constant reassignment led, by mid-May, to the common query among the men, "whose kite are we going to be tail to next?"[152] In fact, this problem affected not only the 1st Maine but all volunteer cavalry regiments in the eastern theater. The Army of the Potomac's cavalry would not serve as a unified force until the upcoming Maryland Campaign.[153]

Culpeper reconnaissance

[edit]The only patrol where the regiment operated as one body was a reconnaissance patrol to Culpeper Court House on Sunday, May 4, 1862, through Monday, May 5.[154] Under BGEN Hartsuff's direction, the 1st Maine took up their line of march Sunday, May 4, 1862, at 17:00, for reconnaissance to the Rappahannock River and beyond Culpeper Courthouse. The expedition was led by MAJ Stowell due to COL Allen's continued infirmity.[155] and the men were tasked with bringing three days rations with them. After proceeding en miles in the darkness, Stowell halted at 20:30 and obtained a local Unionist as guide who took them two miles further to the road along the north side of the Rappahannock. The command then took this road two miles further north to Beverly's Ford. With the water up to five feet deep and a strong current, the regiment did not finish crossing until midnight.[156][note 34]

The guide suggested that the best place for a horse and water was the Cunningham plantation, or Elkwood Plantation, Farley Hill, by Farley Road over Ruffian's Run, the late headquarters of the Confederate Army.[157] Around 01:00, the command gained access to the main house from the overseer who provided valuable intelligence on the geography of Culpeper County and the local rebel order of battle.

At 04:00, the 1st Maine resumed their march, with the overseer guiding them. Instead of taking a dirt track (present day Farley Road) which went through a wood and low land, Stowell accepted the guide's suggestion to ride along Fleetwood Hill that gave a view of the river and railroad as well as of the surrounding country, thus precluding being surprised by the enemy. Pushing on toward Brandy Station, Stowell had thrown out a company of skirmishers and a formidable rear guard, which covered more than a mile of the country.[154]

Stowell found the general appearance of the country favorable, gently rolling, open, highly cultivated, and fruitful, rich plantations, with an abundance of forage and subsistence. He noted the brush was much heavier than about Warrenton Junction. After crossing the river, the men had found no real road leading south and on their left until they arrived at Brandy Station.[154] There they found remains of an old plank road, connecting the Fredericksburg and Culpeper Plank Roads with the Old Carolina and Kelly's Ford Roads.

The patrol found that the rebels on the Rappahannock had fallen back to Gordonsville, and there has been no force this side of there of any great amount. Stowell noted that the "planters on our route, as near as I could judge, are nearly all secesh [sic], and a little bleeding would reduce their fever a little and do them good."[154]

Advancing on from Brandy Station to Culpeper Court House around 09:00, the 1st Maine found that the middle and upper classes were secessionist who could not be trusted to give accurate information, but that the blacks and poor whites were exceptionally reliable, giving corroboration, and very willing to give all the intelligence they had.[154] Two miles beyond Brandy Station, Stowell heard that a line of pickets was established about three miles this side of Culpeper, ergo about two miles ahead of them. Further interrogation of a civilian intercepted coming from the courthouse indicated that the rebels there were two companies of cavalry all equipped with carbines.[158]

After leaving this man by the wayside and advancing about one mile, at 10:15, Stowell received a messenger from CAPT Taylor commander of L Company, the advance guard, that LT Vaughan had found the pickets, charged them, put them to flight, and now Company L and Taylor were chasing them down the railroad. Stowell ordered the column forward as fast as possible. On arriving within a half-mile of the town, he detached men to high ground to the north and south of town to avoid surprises. He next sent two companies forward to support Taylor and Company L which had continued pursuit through the town and out the other side. The men on the high ground reported seeing horses being driven into a yard northwest of town.[159] Stowell sent CAPT Smith forward to investigate.

Not having heard from either Taylor or Smith, Stowell kept the command spread out while he and Company C searched the courthouse and questioned the civilians. While the men in Culpeper were "sour-looking and reserved,"[160] they again found that the black people and handful of Unionists and poor whites were reliable sources. According to the friendly locals, the regiment's approach generated quite a stir, and two couriers immediately rode to the Rapidan, some eight miles beyond Culpeper, for two regiments of infantry which were stationed there. Stowell also learned that the rebels mounted the horses without regard to ownership, and very many without stopping to saddle them. The man intercepted and interrogated on the way in had proven to be accurate as per the composition of the force posted at the courthouse

Considering the short distance to the two regiments of rebel infantry (they were just a few stations up the Orange & Alexandria rail line) and not hearing from CAPT Taylor, Stowell became concerned about the regiment's quite critical situation. While searching stables and yards for horses to seize, the returned CAPT Smith and several company and platoon officers alerted him to a force of cavalry on the south side of the town. Initially thought to be rebels as the force had light-colored horses and some of it light clothing, it turned out to be CAPT Taylor. He had taken some prisoners were riding some of the light-colored horses and dressed in light clothing.[161][note 35]

At 11:00, after finding no papers of great consequence except a handful of rifles, carbines, shotguns, and pistols, the command began its trek back to its base. Stowell remarked that by following the railroad, they could tear up the track at any time if the cars should approach us with infantry. Stopping at Jonas Run about 13:30 to water and feed their horses, and then returned to the Rappahannock by 16:30.[154] Stowell deemed it unwise to stop on the south side for the night, lest rebel infantry catch them by railroad. Since only their cavalry could ford the river, which the Maine troopers did not fear, Stowell turned the column north along the riverbank toward Beverly's Ford as it started top rain.[162][note 36]

Arriving about 18:30, the command began across finding the water about higher than the night before and consequently a difficult two-hour evolution. Originally intending on camping on the north side for the night, Stowell found a consensus to push on home through the stormy weather twelve miles farther.[154]

Stowell cleared the last of his men into camp and reported to COL Allen at 23:00. While not encountering any meaningful contact, the 1st Maine had successfully scouted the furthest distance south over the Rappahannock of any United States unit thus far in the war covering 60 miles over the course of 31 hours and returning with confirmed enemy order of battle, transportation infrastructure intelligence, enemy supply/logistics status, and eight prisoners. The command was duly praised for its competence and professionalism.[154]

Move to Falmouth

[edit]After several successful foraging and scouting expeditions that netted a handful of prisoners, on Friday, May 9, the brigade, now commanded by BGEN Hartsuff, received orders to pack its gear and move to Falmouth, opposite Fredericksburg on the Rappahannock, twenty-five miles to the southeast. On Monday, May 12 at noon, the brigade departed Warrenton.[163] The five companies of the 1st Maine served as advance and rear guards during the march.

At 17:00, after traveling eight miles, Companies D, K, and L, the advance guard, halted and set camp.[164][note 37] The brigade found the travel very difficult, and the rear guard did not arrive at camp until 21:30 Monday evening.[165]

Reveille at 04:00 got the men up to care for their horses and prepare for the day's march. Companies C, F, G, and I rotated to take the advance guard on Tuesday and were stepping out at 06:30. After all the infantry and wagons got out of the camp, D, K, and L finally got on the road at 08:30. COL Allen's command noted the number of "large plantations of rare beauty" along the march.[158] May 13, 1862, was a hot and humid day and the heat almost insufferable, with a dense cloud of dust that made the horses in front of the troopers almost invisible. The infantry in the brigade suffered greatly as the column spun out for miles. The advance guard halted at Stafford Court House at 14:00, but the rear companies did not arrive until 18:30.[165] The men in the brigade were impressed with the relatively untouched countryside, quite amid the spring green, as they passed through.

As the column had progressed during the day, they had attracted a large following of escaped slaves, or "contraband," who seized their freedom by joining the column. Again, these local black residents proved exceedingly valuable sources of intelligence.[166]

The next morning, the Maine troopers rose earlier than their exhausted infantry brothers to prepare their horses for the last leg of the journey south to Falmouth. Again, the companies rotated between advance and rear guard and resumed the march with an awake and fed infantry by 07:00. Within an hour that Wednesday morning, it began raining which spared the brigade from the heat of the day before but added a wet chill to the march.[167]

Hartsuff's brigades's advance guard of Companies D, K, and L reached Falmouth, on the opposite side of the Rappahannock from Fredericksburg, by mid afternoon. The remainder of the brigade streamed in until 20:00.The march of 30 miles through Virginia mud had been difficult. Nearly half of the infantry fallen out by the wayside at some point of the march. Despite the rigor, the 1st Maine troopers noticed several large, beautiful plantations, indicating fine taste. They also noticed again the support and value of the local black population as intelligence sources. The column had met many groups of slaves acting as agents of their own emancipation by escaping to Federal lines.[168]

Falmouth and the Shenandoah Valley

[edit]Through April and May of that spring, the men of the 1st Maine had followed the progress of McClellan in his Peninsula Campaign through the Northern newspaper available in camp as well as the enemy press available along the route of march. The forces at Fredericksburg were commanded by McDowell to block any advance on Washington and to tie down Confederate troops marking them across the river at Fredericksburg. While the confederates had reduced their numbers at Fredericksburg, the U.S. forces increased in number yet did not advance.

While at Falmouth, Hartsuff's brigade with Rickett's brigade now formed a division under a prior commander, Ord, Ord's division was reviewed by Gen. McDowell, and three days later, Friday, May 23, President Lincoln, accompanied by Secretary of War Stanton, M. Mercier, the French Minister, and other distinguished gentlemen, as well as by Mrs. Lincoln, Mrs. Stanton, and other ladies, reviewed McDowell's whole force. In camp at Falmouth, the regiment received new shelter tents (today known as pup tents) so that every two men would always he supplied with a tent for shelter. Despite initial misgivings, the troopers eventually found them much better tents than their original ten- and twelve man tents.[169]

Sunday, May 25, the regiment, with the 2nd Maine Light Battery (CAPT James A. Hall), the 5th Maine Light Battery (CAPT George F. Leppien), and the 1st Pennsylvania Light Battery (CAPT Ezra W. Matthews), all under command of COL Allen, marched to Alexandria. The command was in motion at 18:00 in the evening, and after a tedious march went into bivouac on the road at 23:30, having made five miles in as many hours, owing to continuous delays caused by the artillery and wagons getting stuck in the mud. By 07:00, they were on the road to Alexandria again. At 12:00, however, a courier caught up with COL Allen with orders for them to march to Manassas Junction instead. Allen had the small command go into camp planning on an early start on Tuesday.

McDowell had received reports of the rebels in considerable force near Centreville, and he decided to consolidate his forces at Manassas. On the road by 05:00, the regiment and three batteries bivouacked on the roadside on Tuesday evening and made Manassas by midday, Wednesday, May May 28, joining the remainder of McDowell's corps, camping there that night.

On Thursday morning, Washington ordered McDowell to the Shenandoah Valley to assist Banks so the whole force, with the 1st Maine in the advance, took up the line of march for Front Royal. Washington was intent on this force cutting Jackson's force off in the lower valley between McDowell and Banks.[170]The regiment passed through Thoroughfare Gap and camped Thursday night on the other side of the Blue Ridge Mountains. On Friday, they went fifteen miles further and camped on the estate of the late Chief Justice Marshall, and the third day, Saturday, May 31, reached Front Royal at dark in the rain camping just outside the village on the Manassas Gap Road.[171]

MAJ Whitney's mission

[edit]One week prior to the 1st Maine's arrival as part of Ord's Division, Saturday, May 24, Jackson's forces, after demolishing the 1st Maryland Cavalry at Front Royal, had met their brethren in the 1st Battalion with LTC Douty and driven MGEN Banks' up the other side of the valley to Winchester following up with driving Banks further out of the valley and across the Potomac into Maryland on Sunday. At Front Royal, the regiment met a handful of their comrades from the 1st Battalion who had been captured after The Disaster with MAJ Collins from the 1st Vermont. The day before, Friday May 30, the 1st Rhode Island had liberated these men when MGEN Shields' forces retook the town.[172] Unknown to the regiment, more of their comrades were being held temporarily at several locations in the valley.[173]

At Front Royal, McDowell, now in command, found it very important to open communication with General Banks, who had moved downriver from Williamsport to Harper's Ferry at the lower end of the valley. On Sunday, before his arrival, Shields had heard the artillery fire from Jackson's clash with Fremont at Fisher's Hill but refrained from moving to his assistance because he wanted to wait for McDowell and all of his forces to arrive.[174] While he now knew Jackson may have slipped away at Strasburg, he also wanted to get a picture of the disposition of Confederate forces between him and Winchester, specifically if Jackson and his main body of troops were still threatening Washington. Accordingly, the next day Monday, June 2, he ordered a small force to attempt to make contact. COL Allen upon receiving the orders sent MAJ Whitney with Companies C and D to reconnoiter in that direction, and if possible, open a line of communicate with Banks. The mission was risky as the rebels now commanded the valley.

MAJ Whitney and his little command started late in the afternoon at 16:00. In moderate rain, they traveled up the macadamized Front Royal-Winchester Road, passing through Cedarville and Nineveh without seeing any enemy. The sun set at 19:30 and with the mountains' shadows, it was too dark to continue so Whitney halted his men in the woods about two miles from Winchester. They had heard from the local black population that the Confederates were holding Winchester but that Jackson's main body had already slipped into Strasburg the same day they had arrived ten miles away.[175] This would be valuable intelligence for both Banks and McDowell as well as the fact that they had not seen any rebels troops during their journey in the rain. They remained in the woods that night in a driving rain without fires to hide their presence from the enemy. Without shelter, they were "cold, wet, and decidedly uncomfortable," but the Maine troopers knew the storm and darkness were advantageous to their dangerous mission.[176]

At early dawn, Tuesday, the command dashed into town and through it, creating a complete surprise to the rebel force of about 300 who held the town. This force was left by Jackson to guard about 200 Union soldiers captured by Jackson's forces the week before including a handful of 1st Maine troopers,[173] The rebels had not expected any threat between them and Jackson's main body and failed to put pickets south of the town. They were completely surprised as well as the local citizenry who remembering, "their barbarous conduct toward the retreating troops of General Banks, a few days before, they anticipated a fearful retribution."[177][108][note 38] As the little force, at an hour when few in the town were stirring, swept like a whirlwind into the town, they were very naturally supposed' to be the advance of a heavy force.

The consternation and frightened looks and actions of soldiers and citizens, as well as the joyous surprise of the prisoners, amused the Maine troopers. The panic seized rebel soldiers and the civilians that beds were suddenly vacated, toilets neglected, garments forgotten or ludicrously adjusted, and rebel soldiers threw down their arms in dismay while others took safety in flight. Taking advantage of the enemy's sudden panic and disorganization, many prisoners with their wits about them took off north on the road to Harper's Ferry where friendly forces lay. A few of these men were some captured from LTCOL Douty's battalion at Middletown Several of these men obtained mounts and joined Whitney's expedition.[117]

The whole number of Union prisoners in the town might have been liberated, but since this was not in the mission's orders, Whitney did not stop to do so. His first objective of the mission to scout between Front Royal and Winchester was accomplished. The orders being next to communicate with MGEN Banks and not stop to fight, Whitney's command pushed on. MAJ Whitney found a guide who stated that a rebel force was in camp just beyond Winchester, but instead, after marching a few miles he found Banks' pickets who told him Banks was now at Harper's Ferry. He soon reached the general's headquarters by 10:00, delivered his orders, received new ones, dropped off the liberated Maine troopers with LTC Douty, and started back on the return to Front Royal. Around 17:00, the command once again swept through Winchester again causing confusion and camped in the same woods On Tuesday night that they had on Monday night.[178][note 39] Rising at dawn's light on June 4, the command lit off on the road to Front Royal and met no rebel forces along the way. Arriving by 11:00, MAJ Whitney reported with COL Allen to MGEN McDowell with Banks' messages and his report on rebel dispositions between Front Royal and Winchester.

On that Wednesday, the same day, as a result of Whitney's report of only the handful of rebels at Winchester, Banks moved his command back into Winchester. Entering the town, the U.S. troops found "not a solitary person appeared in sight, but hundreds of unfriendly eyes were peering through all manner of crevices, expecting momentarily to see the torch applied to all places whence shots had been fired and hot water thrown on the morning of the twenty-fifth day of May."[179] In this action, Whitney's colleagues in the 1st Battalion scouted up the Valley Turnpike for Banks.

Separated in the Valley and reunited at Warrenton

[edit]Although all of the elements of the regiment were now operating in the Shenandoah, the army kept them attached to their respective operational commands. Douty and his battalion remained with Banks until after the holiday on the 4th of July. Their days were filled with picket duty, patrolling, scouting, and dispatch riding punctuated by numerous skirmishes of which only the one June 24 merited a mention in official reports.[180] Meanwhile, the rest of the regiment under COL Allen remained with McDowell's forces at Front Royal.[181]

Both locations sent out constant scouting patrols. The Federal forces were in the northern, lower valley around Front Royal and Winchester while the Rebels were in the southern, upper valley around Harrisonburg. The large portion of the valley on either side of Massanutten Mountain was held sporadically by cavalry patrols from Banks and McDowell, and by cavalry and guerrillas by the Confederates. This fluid situation led to men of the regiment taking several prisoners unaware of their presence and, thanks to the support of the local black population escaping the reciprocal situation.[182]

On June 17, the MAJ Stowell was sent with a squadron consisting of Companies K, G, and I returned to Manassas Junction from Front Royal attached to a brigade led by BGEN Hartsuff. . The men in this squadron had an uneventful trek lightened by passing through groves of cherry trees which they scoured of its harvest with the permission of the general. By the 20 June, they were based in Warrenton where COL Allen and the rest of .[183]