1994 Northridge earthquake

An aerial view of destruction | |

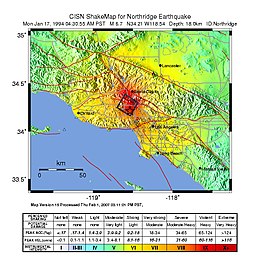

ShakeMap for the event created by the United States Geological Survey | |

| UTC time | 1994-01-17 12:30:55 |

|---|---|

| ISC event | 189275 |

| USGS-ANSS | ComCat |

| Local date | January 17, 1994 |

| Local time | 4:30:55 a.m. PST[1] |

| Duration | 8 seconds |

| Magnitude | 6.7 Mw[2] |

| Depth | 11.31 mi (18.20 km) |

| Epicenter | 34°12′47″N 118°32′13″W / 34.213°N 118.537°W |

| Fault | Northridge Blind Thrust Fault |

| Type | Blind thrust |

| Areas affected | Greater Los Angeles Area Southern California United States |

| Total damage | $13–50 billion |

| Max. intensity | MMI IX (Violent)[1] |

| Peak acceleration | 1.82 g |

| Peak velocity | >170 cm/s |

| Casualties | 57 killed > 8,700 injured |

The 1994 Northridge earthquake affected the Los Angeles area of California on January 17, 1994, at 04:30:55 PST. The epicenter of the moment magnitude 6.7 (Mw) blind thrust earthquake was beneath the San Fernando Valley.[3] Lasting approximately 8 seconds and achieving the largest peak ground acceleration of over 1.7 g, it was the largest earthquake in the area since 1971. Shaking was felt as far away as San Diego, Turlock, Las Vegas, Richfield, Phoenix, and Ensenada.[4] Fifty-seven people died and more than 9,000 were injured.[5][6] In addition, property damage was estimated to be $13–50 billion, making it among the costliest natural disasters in U.S. history.[7][8]

Geology

[edit]The epicenter region of the earthquake was located in the San Fernando Valley, about 30 km (19 mi) northwest of downtown Los Angeles. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) placed the hypocenter's geographical coordinates at 34°12′47″N 118°32′13″W / 34.213°N 118.537°W and at a depth of 11.31 miles (18.20 km).[9] Measuring Mw 6.7, it was the largest earthquake recorded in the Los Angeles area since the 1971 San Fernando earthquake (Mw 6.7). However, unlike the Northridge earthquake, the San Fernando shock occurred on a north–northeast dipping thrust fault beneath the San Gabriel Mountains. Motion during the Northridge event occurred along a south–southwest dipping blind thrust fault beneath the valley. The rupture propagated upward and northwestward along the fault plane for eight seconds at speeds of ~3 km (1.9 mi) per second.[10] The fault planes that produced both earthquakes run parallel to each other.[11] Several other faults experienced minor rupture during the main shock and other ruptures occurred during large aftershocks, or triggered events.[12] The previously undiscovered fault that ruptured in 1994 was subsequently named the Northridge Blind Thrust Fault or Pico Thrust Fault.[13]

Thrust faulting in the northern Los Angeles basin occurs in response to north–south crustal shortening.[14] The fault responsible for the earthquake represented a component of a larger system of faults within the 160 km (99 mi) "Big Bend" stepover of the San Andreas Fault. Crustal compression occurs along this bend of the San Andreas Fault. The Transverse Range and Los Angeles basin hosts east–west striking thrust faults and folds that accommodate over 10 mm (0.39 in) of the compressive motion annually. This zone comprises north and south dipping faults that run subparallel to each other. Most of these faults are buried structures and only a handful reach the surface.[11]

Aftershocks

[edit]Seismic observatories recorded 3,000 aftershocks greater than magnitude 1.5 in the three weeks following the mainshock. By comparing previous aftershock sequences in California against a decay rate equation, the Northridge aftershock activity was highly energetic but decayed marginally quicker than average. The strongest aftershock, measuring Mw 5.9, was recorded one minute after the mainshock. These aftershocks were distributed in three zones; the first zone illuminated a fault structure dipping 35° to 45° at a depth range of 8–19 km (5.0–11.8 mi). Another aftershock zone at shallower depth suggested diffuse tectonic behavior of an anticline above. The third aftershock cluster was in the Santa Susana Mountains after a Mw 5.6 aftershock 11 hours after the mainshock. That event and its aftershocks were distributed along a 10 km (6.2 mi) strike and vertically within the crust, likely associated with faults that did not rupture during the mainshock.[11][15]

Ground effects

[edit]The earthquake caused uplift across 5,000 km2 (1,900 sq mi) including the San Fernando Valley. Global Positioning System observations indicate the maximum uplift was 70 cm (28 in).[11] Direct observations at Oat Mountain suggest the Santa Susana Mountains were thrusted up 40 cm (16 in). Across the northern valley area, uplift was as much as 20–40 cm (7.9–15.7 in). The neighborhood of Northridge was raised 20 cm (7.9 in). The USGS described the surface above the zone of greatest fault displacement as compressed into an "asymmetric dome-shaped uplift". There was also 22 cm (8.7 in) of horizontal deformation which was the largest of its kind measured after the mainshock.[10]

The USGS recorded over 11,000 landslides within 10,000 km2 (3,900 sq mi); most were recorded throughout a 1,000 km2 (390 sq mi) area that comprised the Santa Susana Mountains and ridges north of the Santa Clara River Valley. On average, these documented landslides were under 1,000 m3 (35,000 cu ft), although a significant number of them were larger than 100,000 m3 (3,500,000 cu ft). Rotational block slides were thought to be in the tens or hundreds, including a handful measuring over 100,000 m3 (3,500,000 cu ft). The largest block slide measured 8 million cubic metres (280×106 cu ft). A majority of them occurred in the weak Tertiary to Pleistocene sediments and were previous landslides that became reactivated.[16]

Strong ground motion

[edit]| Main shock Mercalli intensities[17] | |

| MMI | Locations |

|---|---|

| MMI IX (Violent) | Granada Hills, Los Angeles (I-10) Northridge, Santa Monica, Sherman Oaks |

| MMI VIII (Severe) | San Fernando, Hollywood, Reseda Chatsworth, Universal City, Van Nuys |

| MMI VII (Very strong) | Agoura Hills, Beverly Hills, Burbank, Century City Glendale, Downtown, Culver City |

| MMI VI (Strong) | Anaheim, Arcadia, Compton, Oxnard, Palmdale |

| MMI V (Moderate) | Bullhead City, Chino, Inglewood, Long Beach, Westmorland |

| MMI IV (Light) | Barstow, Calexico, El Centro, San Diego |

| MMI III (Weak) | Parker, Las Vegas, Fresno, Santa Maria |

A seismometer at the Cedar Hill Nursery in Tarzana observed the greatest horizontal peak ground acceleration (pga) at 1.82 g, 7 km (4.3 mi) south of the epicenter.[18] The recording was one of the largest observed during an earthquake at the time, yet buildings in the immediate vicinity only sustained broken windows and cracked walls and driveways. It garnered international scientific interest who visited the ranch in the aftermath to install additional instruments to record the aftershocks. The USGS Strong Motion Instrumentation Program ruled out technical malfunction and ground amplification effects, stating that the abnormally high pga recorded by a rock-bolted seismometer was authentic. The same site also recorded an unusually high pga (0.65 g) during a 1987 earthquake, though no abnormal readings were found during earthquakes in 1991 and 1992. USGS seismologist Rufus Catchings suggested the intense shaking was localised and most of the city was unharmed.[19] A possible contributing factor for the effect is the local soil condition and topography. The maximum vertical pga recorded at the same station was 1.18 g.[18]

Several sites in the valley also recorded pga exceeding 1.0 g.[20] There were over 200 recordings of pga exceeding 0.01 g, and the horizontal component pga was larger than average for a reverse-mechanism event. A possible explanation for the high pga is due to the large seismic moment release within a small fault rupture.[11] A peak ground velocity (pgv) of 148 cm (58 in) per second was measured at a station in Granada Hills.[21] At the Sylmar county hospital, 15 km (9.3 mi) north–northeast of the epicenter, the pgv in the horizontal component was 130 cm (51 in) per second. South of the hospital, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power Rinaldi Receiving Station recorded a pgv exceeding 170 cm (67 in) per second.[11]

Damage and fatalities

[edit]

Damage occurred up to 85 miles (137 km) away although it was concentrated in the west San Fernando Valley, and the cities and neighborhoods of Santa Monica, Hollywood, Simi Valley, and Santa Clarita. The Historic Egyptian Theater in Hollywood was red-tagged and closed as was the Capital Theater in Glendale due to structural damage. The exact number of fatalities is unknown, with sources estimating the number to be 60[1][6] or "over 60",[22] to 72,[5] where most estimates fall around 60.[23] The "official" death toll was placed at 57;[5] 33 people died immediately or within a few days from injuries sustained,[24] and many died from indirect causes, such as stress-induced cardiac events.[25][26] Some counts factor in related events such as a man's suicide possibly inspired by the loss of his business in the disaster.[5] More than 8,700 were injured including 1,600 who required hospitalization.[27] Actress Iris Adrian died in September 1994 from complications of a broken hip she suffered in the earthquake.[28]

Sixteen people were killed as a result of the collapse of the Northridge Meadows apartment complex.[29] The Northridge Fashion Center and California State University, Northridge also sustained very heavy damage – most notably the collapse of parking structures. The earthquake also gained worldwide attention because of damage to the vast freeway network, which serves millions of commuters every day. The most notable was to the Santa Monica Freeway, Interstate 10, known as the busiest freeway in the United States, congesting nearby surface roads for three months while the freeway was repaired. Farther north, the Newhall Pass interchange of Interstate 5 (the Golden State Freeway) and State Route 14 (the Antelope Valley Freeway) collapsed as it had 23 years earlier in the 1971 San Fernando earthquake, even though it had been rebuilt with minor improvements to the structural components.[30] LAPD motorcycle officer Clarence Wayne Dean died because of the collapse of the Newhall Pass interchange, falling 40 feet from the damaged connector from southbound 14 to southbound I-5. He likely did not realize until too late in the early morning darkness that the elevated roadway had collapsed. The rebuilt interchange was renamed in his honor a year later.[31]

Additional damage occurred about 50 miles (80 km) southeast in the city of Anaheim, located in Orange County, as the scoreboard at Anaheim Stadium collapsed onto several hundred seats.[32] Most casualties and damage occurred in multi-story wood-frame buildings (such as the three-story Northridge Meadows apartment building). In particular, buildings with an unstable first floor (such as those with parking areas on the bottom) performed poorly.[33] Numerous fires were also caused by broken gas lines from houses shifting off their foundations or unsecured water heaters tumbling.[34] Slope side homes supported on one side by a concrete foundation and stilts on the other were also prone to collapse such as in Sherman Oaks where nine stilt homes crashed down a slope, killing four.[35][36] In the San Fernando Valley, several underground gas and water lines were severed, resulting in some streets experiencing simultaneous fires and floods. Damage to the system resulted in water pressure dropping to zero in some areas; this predictably affected success in fighting subsequent fires. Five days later, it was estimated that between 40,000 and 60,000 customers were still without public water service.[37]

Valley fever outbreak

[edit]An unusual effect of the Northridge earthquake was an outbreak of coccidioidomycosis (Valley fever) in Ventura County. This respiratory disease is caused by inhaling airborne spores of the fungus. The 203 cases reported, of which three resulted in fatalities, constituted roughly 10 times the normal rate in the initial eight weeks. This was the first report of such an outbreak following an earthquake, and it is believed that the spores were carried in large clouds of dust created by seismically triggered landslides.[38] Most of the cases occurred immediately downwind of the landslides.[39]

Night sky

[edit]With the earthquake taking place during the night, and with the power out, many people were able to see a dark night sky for the first time. Emergency services and the Griffith Observatory received many calls from people worried about a "giant, silvery cloud" in the sky, which was identified as being the Milky Way. This anecdote is often used when talking about light pollution.[40][41][42]

Facilities and infrastructure affected

[edit]Hospitals

[edit]Eleven hospitals suffered structural damage and were damaged or rendered unusable.[27] Not only were they unable to serve their local neighborhoods, but they also had to transfer out their inpatient populations, which further increased the burden on nearby hospitals that were still operational. As a result, the state legislature passed a law requiring all hospitals in California to ensure that their acute care units and emergency rooms would be in earthquake-resistant buildings by January 1, 2005. Most were unable to meet this deadline and only managed to achieve compliance in 2008 or 2009.[43]

Television, movie, and music productions

[edit]The production of movies and TV shows was disrupted. At the time of the quake, before dawn on Monday morning, the Warner Bros. film Murder in the First (with Christian Slater, Kevin Bacon, and Gary Oldman) was being filmed only four miles (6.4 km) from the epicenter. Production came to a halt. The main courtroom set was in shambles. The building containing the set was later "red tagged" as unsafe due to the damage it sustained.[citation needed] The Star Trek: Deep Space Nine episode "Profit and Loss" was being filmed at the time, and actors Armin Shimerman and Edward Wiley left the Paramount Pictures lot in full Ferengi and Cardassian makeup, respectively.[44] The season five episode of Seinfeld entitled "The Pie" was due to begin shooting on January 17 before stage sets were damaged. Also, ABC's General Hospital set at ABC Television Center suffered partial structural collapse and water damage.

An earthquake scene was written in the screenplay of Wes Craven film New Nightmare and the earthquake occurred in the middle of its production timeline. Subsequently, the production company, Warner Bros., incorporated real-life footage of the earthquake aftermath into the final cut.[45][46]

Some archives of film and entertainment programming were also affected. For example, the original 35 mm (1.4 in) master films for the 1960s sitcom My Living Doll were destroyed.[47]

Transportation

[edit]

Portions of a number of major roads and freeways, including Interstate 10 over La Cienega Boulevard, and the interchanges of Interstate 5 with California State Route 14, 118, and Interstate 210, were closed because of structural failure or collapse.[48][49] James E. Roberts was chief bridge engineer with Caltrans and was placed in charge of the seismic retrofit program for Caltrans until his death in 2006.

Rail service was briefly interrupted, with full Amtrak and expanded Metrolink service resuming in stages in the days after the quake. Interruptions to road transport caused Metrolink to experiment with service to Camarillo in February and Oxnard in April,[50][51] which continues today as the Ventura County Line, and extended the Antelope Valley Line almost ten years ahead of schedule. Six new stations opened in six weeks.[52] Metrolink leased equipment from Amtrak, San Francisco's Caltrain, and Toronto, Canada's GO Transit to handle the sudden onslaught of passengers. Amtrak ceased service in the Pasadena Subdivision following structural damage to a rail bridge in Arcadia and redirected all rail traffic through Riverside and Fullerton.[53] All MTA bus lines operated service with detours and delays on the day of the quake. Los Angeles International Airport and other airports in the area were also shut down as a 2-hour precaution, including Burbank-Glendale-Pasadena Airport (now Hollywood Burbank Airport) and Van Nuys Airport, which is near the epicenter, where the control tower suffered from radar failure and panel collapse. The airport was reopened in stages after the quake.

California State University, Northridge

[edit]California State University, Northridge, was the closest university to the epicenter. Many campus buildings were heavily damaged and a parking structure collapsed. Many classes were moved to temporary structures.[54] Much of the campus infrastructure were damaged and there were multiple fires and explosions throughout the campus.[55] The earthquake damaged several buildings and destroyed all communications, including telephone lines, and caused computer systems to shut down. Two CSUN students died at the Northridge Meadows Complex along with 14 other residents.[56]

Campus damage

[edit]All 58 buildings on campus sustained significant damage, resulting in a $406 million recovery effort.[57] The Oviatt Library experienced both interior and exterior damage, but the overall frame of the central part of the building remained stable, allowing student use to continue.[58] In the Science Complex, Building #1 and #2 suffered fire damage while the bridges connecting buildings #3 and #4 were closed and named unstable.[59] The University Tower apartments, Fine Arts Building and the South Library were damaged beyond repair and demolished. Photographs of the recently constructed Parking Structure C which collapsed became synonymous with the earthquake's effects on the university.[60]

Classes and enrollment

[edit]The damage delayed the start of the 1994 Spring semester by two weeks. The campus mobilised 335 makeshift structures for its usage.[61] Some 25 classes were held at Pierce College, LA City College and UCLA, while others were outdoors or in trailer buildings.[60] The campus was unable to use any of its classrooms because of the damage the buildings sustained. CSUN President Dr. Blenda Wilson assured the rental of temporary structures to be placed in available spaces throughout the campus. An estimated $350 million (equivalent to $720 million today) was used to supply the number of trailers and domes which housed classes and administration offices. Enrollment dropped by approximately 1,000 students, leaving some homeless as dormitories were closed due to damage that rendered them unsafe and which required repair.[62]

External resources

[edit]The seismic event led to millions of dollars worth of damage resulting in a sharp drop in student enrollment. CSUN received financial assistance for its efforts in reestablishing the damaged buildings with monetary gifts from the McCarthy Foundation, the Common Wealth Fund, and the Union Bank Foundation. In addition, the campus received a $23,000 check (equivalent to $47,000 today) from the Los Angeles Times Valley Edition for the journalism department.[63] CSUN also received assistance from government agencies FEMA and OES to support the recovery effort and serve the needs of the local community.[64] UCLA's Westwood campus opened their doors and allowed CSUN students to use their libraries while providing shuttle buses to and from the university.[65]

Entertainment and sports

[edit]Universal Studios Hollywood shut down the Earthquake attraction, based on the 1974 motion picture blockbuster, Earthquake. It was closed for the second time since the Loma Prieta earthquake. Angel Stadium of Anaheim (then known as Anaheim Stadium) suffered some damage when the scoreboard fell into the seats,[32] forcing a Mickey Thompson Entertainment Group off-road race at the ballpark to be postponed from that upcoming weekend to February 12.[66]

Other buildings

[edit]Numerous Los Angeles museums, including the Art Deco Building in Hollywood, were closed, as were numerous city shopping malls. Gazzarri's nightclub suffered irreparable damage and had to be torn down. The city of Santa Monica suffered significant damage. Many multifamily apartment buildings in Santa Monica were yellow-tagged and red-tagged. An especially hard hit area was between Santa Monica Canyon and Saint John's Hospital, a linear corridor that suffered a significant amount of property damage. The City of Santa Monica provided assistance to landlords dealing with repairs so tenants could return home as soon as possible. In Valencia, the California Institute of the Arts experienced heavy damage, with classes relocated to a nearby Lockheed test facility for the remainder of 1994. The Los Angeles Unified School District closed local schools throughout the area, which reopened one week later. UCLA and other local universities were also shut down. The University of Southern California suffered some structural damage to several older campus buildings, but classes were conducted as scheduled. Pierce College suffered $2 million in damages, the most affected of the nine Los Angeles community colleges.[67]

Aftermath

[edit]Lifestyle disruptions in the weeks following

[edit]In the weeks following the quake, many San Fernando Valley residents had either lost their homes entirely or experienced structural damage too severe to continue living in them without making repairs. Although the vast majority of homes in the area, with the exception of a few particular neighborhoods, were relatively unaffected; many feared an aftershock to rival or exceed the severity of the first one. While a notable aftershock never came, many residents opted to stay in shelters or live with friends and family outside the area for a short time following.[68]

While many businesses remained closed in the days following the quake, some infrastructure was not able to be rebuilt for months, even years later. The daily commute for many drivers in the weeks following was significantly lengthened, notably for those traveling between Santa Clarita and Los Angeles, and commuters on I-10 traveling to and from the Westside. Additionally, many businesses were forced to relocate or use temporary facilities in order to accommodate structural damage to their original locations or the difficulty accessing them. Some people even made temporary relocations closer to their jobs while their homes or neighborhoods were being rebuilt.

State legislative response

[edit]The Northridge earthquake led to a number of legislative changes. Due to the large amount lost by insurance companies, most insurance companies either stopped offering or severely restricted earthquake insurance in California. In response, the California Legislature created the California Earthquake Authority (CEA), which is a publicly managed but privately funded organization that offers minimal coverage.[69] A substantial effort was also made to reinforce freeway bridges against seismic shaking, and a law requiring water heaters to be properly strapped was passed in 1995.

Engineering analysis

[edit]The analysis of the effect of Northridge earthquake on behavior of structures has been investigated by many researchers. For example, the behavior of underground walls has been evaluated for the Northridge earthquake using numerical methods. The comparison of the seismic behavior of underground braced walls with ACI 318 design method reveals that bending moment and shear force of the walls under Northridge earthquake loads were observed to reach 2.8 and 2.7 times as large as the respective allowable limits. Therefore, caution should be taken in seismic design of diaphragm walls using ACI 318 code requirements.[70]

In popular culture

[edit]- The Northridge Earthquake was the subject of the 1995 film Epicenter U., a first-hand account of healing from the natural disaster, directed by Alexis Krasilovsky.[71][72] The Earthquake Haggadah (1995) was a video excerpt from Epicenter U. narrated by Wanda Coleman. Distributed in 3/4" and VHS by the Poetry Film Workshop circa 1998. Re-released as part of the DVD Some Women Writers Kill Themselves in 2008.

- The Northridge earthquake was used as a plot device in the 2004 film A Cinderella Story. The film is a modern retelling of the Cinderella classic starring Hilary Duff and Chad Michael Murray. In it, Duff's character, Sam Montgomery, lives in the San Fernando Valley with her father, stepmother, and two stepsisters. Her father, Hal, perishes in the quake trying to save her stepmother, setting the story in motion.[73]

- A song about the earthquake, set to the tune of "Happy Farmer", was featured in the Animaniacs episode "A Quake, A Quake!".[74]

- The title of the song play I Was Looking at the Ceiling and Then I Saw the Sky by John Adams and June Jordan was a quote from an earthquake survivor.[75] The story's premise also takes places after an earthquake.[76]

See also

[edit]- 1987 Whittier Narrows earthquake

- 1992 Landers earthquake

- 1999 Hector Mine earthquake

- 2019 Ridgecrest earthquakes

- List of earthquakes in 1994

- List of earthquakes in California

- List of earthquakes in the United States

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Historic Earthquakes". Archived from the original on December 1, 2016. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ^ ANSS: Northridge 1994 .

- ^ ANSS. "Northridge 1994: 6.7 – 1 km NNW of Reseda, CA". Comprehensive Catalog. U.S. Geological Survey.

- ^ "M 6.7 – Northridge – Impact". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved November 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Reich, K. Study raises Northridge quake death toll to 72. Los Angeles Times December 20, 1995

- ^ a b Miller, Devon (January 17, 2021). "Remembering The Northridge Earthquake 27 Years Later". The Valley Post. Archived from the original on May 25, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ "1994 Quake Still Fresh in Los Angeles Minds". Los Angeles Daily News. January 11, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2021.

- ^ National Geophysical Data Center / World Data Service (NGDC/WDS): NCEI/WDS Global Significant Earthquake Database. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (1972). "Significant Earthquake Information". doi:10.7289/V5TD9V7K.

- ^ "M 6.7 – 1 km NNW of Reseda, CA". Earthquake Hazards Program. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ a b "Studying the Setting and Consequences of the Earthquake". USGS Response to an Urban Earthquake: Northridge '94 (Report). Open-File Report 96-263. United States Geological Survey. 1996. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f U.S. Geological Survey; Southern California Earthquake Center (October 21, 1994). "The Magnitude 6.7 Northridge, California, Earthquake of 17 January 1994" (PDF). Science. New Series. 266 (5184). American Association for the Advancement of Science: 389–397.

- ^ "Southern California Earthquake Data Center". Caltech. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ^ "1994 Northridge Earthquake". Southern California Earthquake Data Cente, Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ Hauksson, Egill; Jones, Lucile M. (1995). "Seismology: The Northridge Earthquake and its Aftershocks". SCEC Contribution #138. Southern California Earthquake Center. Retrieved July 9, 2024.

- ^ Douglas Dreger. "The Large Aftershocks of the Northridge Earthquake and their Relationship to Mainshock Slip and Fault Zone Complexity". Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- ^ Harp, Edwin L.; Jibson, Randall W. (1996). "Landslides triggered by the 1994 Northridge, California, earthquake". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 86 (1B): S319–S332. doi:10.1785/BSSA08601BS319.

- ^ Dewey, James W.; Reagor, B. G.; Dengler, L.A.; Moley, Kathy (1995). "Intensity distribution and isoseismal maps for the Northridge, California, earthquake of January 17, 1994". Open-File Report. USGS Numbered Series. 95–92. United States Geological Survey. doi:10.3133/ofr9592.

- ^ a b Yegian, M.K.; Ghahraman; Gazetas, G.; Dakoulas, P.; Makris, N. (April 1995). "The Northridge Earthquake of 1994: Ground Motions and Geotechnical Aspects" (PDF). Third International Conference on Recent Advances in Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Soil Dynamics. Northeastern University College of Engineering. p. 1384. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 6, 2013. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- ^ Colvin, Richard L. (February 18, 1994). "Tarzana Jolt : Shaking Under Nursery Is Among Strongest Ever". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ "Significant Earthquakes of the World 1994". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on December 22, 2009. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ Luco, Nicolas (2019). "Seismic design and hazard maps: Before and after" (PDF). Structure. National Council of Structural Engineers Associations: 28–30.

- ^ "FEMA". Archived from the original on March 15, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- ^ "History Channel". Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- ^ Peek-Asa, C.; et al. (1998). "Fatal and hospitalized injuries resulting from the 1994 Northridge earthquake". International Journal of Epidemiology. 27 (3): 459–465. doi:10.1093/ije/27.3.459. PMID 9698136.

- ^ Kloner, R. A.; et al. (1997). "Population-Based Analysis of the Effect of the Northridge Earthquake on Cardiac Death in Los Angeles County, California". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 30 (5): 1174–1180. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00281-7. PMID 9350911.

- ^ Leor, J.; et al. (1996). "Sudden cardiac death triggered by an earthquake". The New England Journal of Medicine. 334 (4): 413–419. doi:10.1056/NEJM199602153340701. PMID 8552142.

- ^ a b "Executive Summary". Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved June 8, 2007.

- ^ "Obituary: Iris Adrian". The Independent. October 23, 2011. Archived from the original on May 1, 2022.

- ^ "25 Years Later: The Desperate Search for Survivors at Northridge Meadows Apartments" (with video). NBC News Los Angeles. January 18, 2019 [January 15, 2019].

- ^ "Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology". Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on April 3, 2006. Retrieved March 25, 2006.

- ^ "Interchange Named for Officer Who Died in Quake". Los Angeles Times. July 8, 1994.

- ^ a b Spencer, Terry (January 18, 1994). "Earthquake: Disaster Before Dawn: Scoreboard Crashes Onto Seats in Anaheim Stadium: Collapse: The 17.5-ton Sony 'Jumbotron' also destroyed a section of roof as it broke loose and fell to the left-field upper deck". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Schleuss, Jon; Lin, Rong-Gong II (November 22, 2019). "Dangerous L.A. apartment buildings most at risk in an earthquake are quickly being fixed". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Secure Your Stuff: Water Heater". Archived from the original on May 3, 2007. Retrieved June 8, 2007.

- ^ NAHB Research Center (July 30, 1994). Assessment of Damage to Residential Building Caused by the Northridge Earthquake (PDF) (Report). U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research.

- ^ Aurelius, Earl, ed. (1994). "Residential Buildings". The January 17, 1994 Northridge, CA Earthquake: An EQE Summary Report. EQE International (Report).

- ^ Scawthorn; Eidinger; Schiff, eds. (2005). Fire Following Earthquake. Reston, VA: ASCE, NFPA. ISBN 978-0-7844-0739-4. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ Schneider, E., Hajjeh, R. A., Der Spiegel, R. A., Jibson, R. W., Harp, E. L., Marshall, G. A., . . . Werner, S. B. (1997). A coccidioidomycosis outbreak following the Northridge, Calif, earthquake. Jama, 277(11), 904-908.

- ^ "Coccidioidomycosis Outbreak". United States Geological Survey Landslide Hazards Program. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014.

- ^ "Connect with the Galaxy: A case for turning out the lights – Night Skies (U.S. National Park Service)". National Parks Service. Retrieved September 15, 2024.

- ^ "Lights Out". Eastside Audubon Society. Retrieved September 15, 2024.

- ^ Sharkey, Joe (August 30, 2008). "Helping the Stars Take Back the Night". The New York Times. Retrieved September 15, 2024.

- ^ Cheevers, Jack; Abrahamson, Alan (January 19, 1994), "Earthquake: The Long Road Back: Hospitals Strained to the Limit by Injured: Medical care: Doctors treat quake victims in parking lots. Details of some disaster-related deaths are released", Los Angeles Times

- ^ Erdmann, Terry J.; Paula M. Block (2010). Star Trek: Deep Space Nine Companion. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-50106-8.

- ^ Peitzman, Louis (October 15, 2014). "How 'New Nightmare' Changed the Horror Game". BuzzFeed. Retrieved October 24, 2017.

- ^ Horn, Shawn Van (February 24, 2024). "The Wes Craven Horror Movie That Survived an Earthquake". Collider. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ Susan King, "The 'perfect' '60s woman", Los Angeles Times, April 4, 2012. Retrieved April 14, 2012

- ^ Weinraub, Bernard (January 18, 1994). "The Freeways; Collapsed Freeways Cripple City Where People Live Behind Wheel". The New York Times. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ Taylor, Alan. "The Northridge Earthquake: 20 Years Ago Today – Info and images of collapsed freeways". The Atlantic. Retrieved June 25, 2019.

- ^ Mitchell, J. E. (January 25, 1994). "Camarillo Gets a Little Good News: MetroLink Is Coming". Los Angeles Times. p. B6. Retrieved March 23, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Catania, Sara (April 4, 1994). "Last of Post-Quake Metrolink Stations Opening in Oxnard". Los Angeles Times. p. B5. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ Gbenekama, Delana G. (October 2012). Metrolink 20th Anniversary Report (PDF). HWDS and Associates, Inc. pp. 9, 48. Retrieved May 21, 2018.

- ^ Hymon, Steve (March 5, 2016). "Photos: Gold Line Foothill Extension's opening day". thesource.metro.net. Retrieved March 9, 2016.

- ^ Chandler, John; Johnson, John-Us (February 15, 1994). "Quake-Ravaged CSUN Reopens Amid Confusion". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ Heistand, Jesse (1994). "Science Complex Explodes". Daily Sundial.

- ^ Saringo-Rodriguez, John (January 17, 2014). "20 Years after Northridge Earthquake, CSUN Is Not Just Back, Better". sundial.csun.edu.

- ^ Moore, Solomon (1999). "Education: Three-story Monterey Hall and Five-story Administration Structure Are among Last Campus Construction Projects Related to the 1994 Earthquake". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Collins, Michael (March 1, 1994). "Temporary library may ease traveling headaches over hill". Daily Sundial.

- ^ Heistand, Jesse (January 24, 1994). "Science Complex Explodes". Daily Sundial.

- ^ a b Torres, Maria L. (January 10, 2024). "Northridge Quake "Thrashed" CSUN, But the Campus Reopened and Thrived". San Fernando Valley Sun. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ Gallegos, Emma G. (January 17, 2014). "Things You Might Not Have Known About The Northridge Earthquake". LAist. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ Lebrun, Chris (February 24, 1994). "Slight Drop in CSUN Enrollment Attributed to Quake". Daily Sundial.

- ^ Kastle (March 1, 1994). "CSUN Grateful for Grants and Donations". Daily Sundial.

- ^ Symes, Michael (March 1, 1994). "FEMA Opens CSUN Office". Daily Sundial.

- ^ Chandler, John (March 17, 1994). "On the Road to Research : CSUN: Grateful students are shuttled to UCLA libraries. But there are problems". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ Shepard, Eric (January 19, 1994). "Trojan Game Moved: Earthquake: USC will play Arizona State at Lyon Center because of possible damage". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ "Valley Perspective : Pierce College Deserves Community's Support : School Needs Neighbors' Sympathy, Earthquake Relief". Los Angeles Times. March 27, 1994. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ "The Northridge Earthquake: 20 Years Ago Today". The Atlantic. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- ^ "CA Earthquake Authority". Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ^ Bahrami, M.; Khodakarami, M.I.; Haddad, A. (April 2019). "Seismic behavior and design of strutted diaphragm walls in sand". Computers and Geotechnics. 108: 75–87. Bibcode:2019CGeot.108...75B. doi:10.1016/j.compgeo.2018.12.019. S2CID 128226913.

- ^ "'Epicenter U.' Captures Earthquake Aftermath: Education: CSUN film students' work documents frustration, anxiety and hope that followed the devastating temblor". Los Angeles Times. October 5, 1994.

- ^ Slater, Eric. "Student Cinema Verite Examines Earthquake," Los Angeles Times, Metropolitan Digest, October 11, 1994, p. B2.

- ^ Crust, Kevin (July 16, 2004). "Midnight can't come too soon". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 1, 2022.

- ^ Elliot, Austin (January 21, 2013). "Yakko, Wakko, and Dot recount the Northridge quake". American Geophysical Union. Retrieved March 1, 2022.

- ^ Maddocks, Fiona (July 10, 2010). "I Was Looking at the Ceiling and Then I Saw the Sky; Icarus at the Edge of Time; Don Giovanni". The Guardian. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ Hamlin, Jesse (May 7, 1995). "What's Shakin' With Adams And Sellars? / Composer and director team anew -- this time with poet June Jordan -- an earthquake-inspired love story / 'I Was Looking at the Ceiling and Then I Saw the Sky'". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Southern California Earthquake Data Center

- USGS Pasadena Archived June 6, 2003, at the Wayback Machine

- USC Earthquake Engineering-Strong Motion Group

- SAC Steel Project (Study of welded steel failures)

- Helicopter Footage Filmed After The Quake

- City of Los Angeles Re-survey of the San Fernando Valley

- Film "Epicenter U."

- Film "Earthquake Haggadah, The"

- The International Seismological Centre has a bibliography and/or authoritative data for this event.

- Earthquakes in California

- 1994 in California

- Disasters in Los Angeles

- Geology of Los Angeles County, California

- History of Los Angeles

- History of the San Fernando Valley

- Northridge, Los Angeles

- Santa Susana Mountains

- 1994 earthquakes

- April 1994 events in the United States

- 1994 natural disasters in the United States

- January 1994 events in the United States

- Buried rupture earthquakes