1932 Cuba hurricane

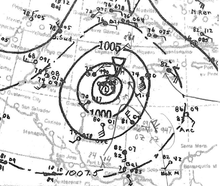

Surface weather analysis of the hurricane at its peak intensity on November 8, southwest of Cuba | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | October 30, 1932 |

| Dissipated | November 14, 1932 |

| Category 5 major hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 175 mph (280 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | ≤915 mbar (hPa); ≤27.02 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 3,103+ (Deadliest in Cuban history) |

| Damage | $40 million (1932 USD) |

| Areas affected |

|

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1932 Atlantic hurricane season | |

The 1932 Cuba hurricane, known also as the Hurricane of Santa Cruz del Sur[1] or the 1932 Camagüey hurricane,[2] was the deadliest and one of the most intense tropical cyclones on record to have made landfall in Cuba. It is the only Category 5 Atlantic hurricane ever recorded in November. The cyclone had a path through the Caribbean Sea atypical to most hurricanes developing late in the Atlantic hurricane season. The storm's strong winds, storm surge, and rain devastated an extensive portion of central and eastern Cuba, where the storm was considered the worst natural disaster of the 20th century. Though the effects from the hurricane were concentrated primarily on Cuba, significant effects were also felt in the Cayman Islands and the Bahamas, with lesser effects felt elsewhere.

The tropical depression that would later develop into the destructive hurricane was first located east of the Lesser Antilles on October 30, and tracked westward into the Caribbean Sea, reaching tropical storm strength the next day. Moving southwestward towards the southern portion of the Caribbean, the storm reached hurricane strength on November 2 before a period of rapid intensification ensued. On November 6, the tropical cyclone reached its peak intensity as a Category 5 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 175 mph (280 km/h). The storm weakened to Category 4 intensity while recurving northeast, moving ashore Cuba's Camagüey Province on November 9 with winds of 150 mph (240 km/h). After traversing the island, the storm gradually weakened as it crossed the central Bahamas Islands and near Bermuda. On November 13, the system transitioned into an extratropical cyclone and dissipated the next day.

As an intensifying hurricane in the southern Caribbean Sea, the storm moved near the Netherlands Antilles and Colombia, causing widespread effects. A prolonged passage of Curacao resulted in the damaging of the harbor fortification. The storm lashed the coast of Colombia with strong winds and torrential rainfall, severely hampering the banana crop in the region and disrupting telecommunications. Several towns, particularly those near the coast, sustained significant infrastructural damage. Marked, albeit localized, damage to banana crops was also reported in Jamaica, where strong winds toppled numerous trees. In open waters, the storm's track brought it across numerous shipping lanes, largely disrupting shipping primarily in the central Caribbean and damaging several ships.

Meteorological history

[edit]

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

The 1932 Cuba hurricane can be traced back to a tropical depression, first identified at 06:00 UTC on October 30 by ship observations roughly 200 mi (320 km) east of Guadeloupe.[3][4] Tracking generally westward, the depression crossed the Lesser Antilles the next day between Dominica and Martinique.[3] Barometric pressures decrease to as much as 1008 mbar (hPa; 29.77 inHg) in St. Lucia confirmed the presence of a developing tropical cyclone.[1] Shortly after traversing the islands, the disturbance strengthened to tropical storm intensity at 18:00 UTC on October 31.[3] Concurrently as the storm was gradually intensifying, the tropical cyclone began to take an unusual course towards the southwest.[4] On November 2, the storm intensified to hurricane status while north of the Netherlands Antilles.[3]

Steadily strengthening, the hurricane reached Category 2 status on November 3.[3] During the day, the storm passed approximately 50 mi (80 km) north of Punta Gallinas in Colombia, the northernmost extent of South America.[4] However, at the same time the hurricane curved towards the west, causing the storm to move away from Colombia and Venezuela.[3] During the next few days, the hurricane rapidly intensified, reaching major hurricane status late on November 4. The next day, the hurricane's intensity was analyzed to have been the equivalent of a modern-day Category 5 hurricane while curving northward.[3] Although the storm was analyzed operationally to have peaked as a minimal Category 4 hurricane, reanalysis of the hurricane indicated that the tropical cyclone was much more intense than initially suggested based on observations by the S.S. Phemius, the crew of which visually estimated winds of around 200 mph (320 km/h) at the maximum of the storm and measured unusually low pressures.[1] Early on November 6, the hurricane peaked with maximum sustained winds estimated at 175 mph (280 km/h).[3] During that time, the S.S. Phemius recorded a minimum barometric pressure of 915 mbar (hPa; 27.02 inHg); this measurement was the lowest documented throughout the storm's existence. As this report did not occur within the hurricane's eye, the storm's true minimum pressure may have been much lower.[1]

Pacing northward, the hurricane gradually weakened after maximum intensity on November 6 but held its Category 5 strength for 78 consecutive hours before finally dropping to Category 4 status.[3] Due to a gradual curve towards the northeast, the hurricane tracked near Cayman Brac on November 9;[1] a minimum barometric pressure of 939 mbar (hPa; 27.73 inHg) was documented on the island. Only slight weakening occurred before the hurricane made landfall on the Caribbean coast of Cuba's Camagüey Province at 14:00 UTC that day. At the time of landfall, the tropical cyclone was estimated to have had a minimum pressure of 918 mbar (hPa; 27.11 inHg) and maximum sustained winds of 150 mph (240 km/h), with these winds extending as far as 40 mi (65 km) from the center of the hurricane. The storm traversed Cuba in six hours before emerging into the Atlantic Ocean late on November 9, after which it began to cross the central Bahamian archipelago. At 07:00 UTC on November 10, the hurricane made a second landfall on Long Island, Bahamas with an intensity equivalent to that of a modern-day Category 3. Continuing to track northeast, the storm moved east of Bermuda two days later.[1] On November 13, the hurricane began to interact with an extratropical cyclone centered over the Canadian Maritimes,[1][4] and later weakened to tropical storm strength.[3] The tropical cyclone later became extratropical itself before it was last noted at 18:00 UTC on November 14.[3]

Records

[edit]Among Atlantic hurricanes, this storm had the longest duration at Category 5 intensity, the highest category of the Saffir–Simpson scale. It was also the strongest November Atlantic hurricane.

Preparations and impact

[edit]

As the hurricane moved slowly through the eastern and southern Caribbean, the rough seas and strong winds disrupted shipping routes. On November 6, the American schooner Abundance encountered the storm east of Jamaica, resulting in a destroyed rudder and a beaching on Jamaica's Morant Point.[5][6] However, the ship's six crew were extracted from the disabled vessel and were transported to the United States.[5] Although the S.S. Phemius would later return safely to port in Cuba,[1] reports that the ship had lost its smokestack and the relaying of an SOS message prompted the United Fruit Company liner Tela to search for the initially missing ship, which failed due to poor visibility conditions.[5][7] This was followed by a search operation undertaken by the USS Overton (DD-239) and USS Swan (AM-34).[8] On November 8, the S.S. Phemius was found damaged and later towed to shore by a salvage tug. However, during the same period of time both the steamer Tacira and the freighter San Simeon were disabled after encountering the storm, requiring towing to safety.[9] Several other ships in the immediate area were also hampered by the storm.[10]

A novel based on the ordeal of the Phemius and her crew, In Hazard, was later written by Richard Hughes and published in 1938.

Some damage was reported in northern South America as the hurricane swept near the coast. In Colombia, rail telecommunications were interrupted near Santa Marta, and banana plantations in the area were believed to have suffered to some extent due to the storm's winds and rain.[5] In Santa Marta itself, several homes were inundated and automotive traffic was hampered by the storm's effects. Docks on Santa Marta's port were also damaged.[11] Heavy rains also washed out some railways and bridges, further disrupting the distribution of banana shipments.[12][13] Elsewhere along the coast, many of Colombia's seaports were damaged by the storm's effects, while inland farms suffered extensive flood damage.[14] Due to sparse reports from the remainder of Colombia,[15] the extent of damage in Barranquilla remains unspecified,[5] with other nearby towns reporting "heavy" damage.[15] The village of Sevilla in the municipality of Zona Bananera, Magdalena was almost entirely destroyed.[16] Providencia Island just off of Colombia sustained significant agricultural damage and the loss of 36 homes.[4] To the northeast in Curacao, the passing hurricane destroyed the island harbor's fortifications.[14] A seawall near the entrance to Sint Anna harbor suffered partial collapse, while a pontoon bridge linking both sides of the harbor was completely destroyed. In nearby Bonaire, a pier succumbed to the driving rain and rough seas.[17]

With the hurricane threatening Jamaica, Pan American World Airways cancelled its flights servicing Kingston, Jamaica.[18] In Jamaica, the storm's passage to the west caused intense winds as strong as 71 mph (114 km/h) to sweep across the island,[19] destroying over 2 million trees.[20] Although effects overall were generally minimal, some localized areas on the island experienced as much as a 50% loss of banana trees due to the storm.[4] The cost of damage on Jamaica was US$4 million.[21]

Cayman Islands

[edit]The storm devastated the Cayman Islands, especially Cayman Brac which was inundated by the storm surge, which was reported to be as high as 10 m (33 ft). Many homes and buildings were washed out to sea as a result of the storm and many people had to climb trees to escape the floodwaters. 110 people died on the islands; one of them was on Grand Cayman, 69 died on Cayman Brac, and 40 were lost on ships at sea.[22][23] The ship Balboa also sank in the George Town harbor as a result of the storm.[24]

Cuba

[edit]Although no warnings were issued initially, the National Observatory of Cuba voiced concerns that the intense tropical cyclone presented a danger to Cuba, particularly Camagüey Province, as early as November 5. However, the observatory indicated that forecasting the future motion of the hurricane was difficult as the storm's intensity and previous motion was not consistent with climatology.[25] On November 8, a hurricane warning was issued for the southeastern extent of Cuba.[26] As a precautionary measure, shipping routes servicing ports in eastern Cuba were suspended.[27]

The town of Santa Cruz del Sur in Camagüey Province was virtually obliterated by a massive storm surge which measured 6.5 m (21.3 ft) in height.[28] Few buildings remained standing in the area. In that coastal town alone, a total of 2,870 people lost their lives. In total, 3,033 people died in Cuba and damage there was estimated at $40 million (1932 USD; $890 million today).[28]

See also

[edit]- List of deadliest Atlantic hurricanes

- List of Category 5 Atlantic hurricanes

- 1924 Cuba hurricane – A powerful hurricane that made landfall on Cuba at Category 5 intensity

- Hurricane Flora (1963) – Stalled over eastern Cuba, causing widespread flooding and numerous deaths

- Hurricane Ike (2008) – The second costliest tropical cyclone in Cuban history; traversed the length of Cuba and exacerbated impacts from preceding storms earlier in the year

- Hurricane Paloma (2008) – An intense November hurricane which struck the same areas of Cuba as the 1932 hurricane with lesser, but still significant, effects

- Hurricane Irma (2017) – The last Category 5 hurricane to make landfall on Cuba, and the costliest hurricane in Cuban and Leeward Islands history

- Hurricane Eta (2020) – A strong Category 4 hurricane in November 2020 and was the third most intense November hurricane on record

- Hurricane Iota (2020) – A Category 4 hurricane that occurred 2 weeks after Eta in November 2020 and was the second most intense November hurricane on record

References

[edit]- General

- José Carlos Millás; Observatorio Nacional; Secretaria De Agricultura, Comercio Y Trabajo (1933). Memoria Del Huracán De Camagüey De 1932 (PDF) (Report). Havana, Cuba: United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- Specific

- ^ a b c d e f g h Landsea, Chris; et al. (April 2014). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ^ Millás, p. 1

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved December 28, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Landsea, Chris (April 2022). "The revised Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT2) - Chris Landsea – April 2022" (PDF). Hurricane Research Division – NOAA/AOML. Miami: Hurricane Research Division – via Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory.

- ^ a b c d e f Mitchell, C.L.; United States Weather Bureau (November 1932). "The Tropical Storm Of October 30–November 13, 1932" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 60 (11). Washington, D.C.: American Meteorological Society: 222. Bibcode:1932MWRv...60..222M. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1932)60<222:TTSOON>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Tropic Storm Coming North". The Daily Northwestern. Vol. 65. Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Associated Press. November 7, 1932. p. 1. Retrieved September 3, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Ships Suffer As Caribbean Gale Strikes". The San Bernardino County Daily Sun. Vol. 39. Associated Press. November 7, 1932. p. 1. Retrieved September 3, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "3 Ships Adrift in Caribbean As Hurricane Force Grows". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Vol. 92, no. 311. New York City, New York. Associated Press. November 8, 1932. p. 3. Retrieved September 6, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "U.S. Warships Sent To British Ship's Aid". The Reading Times. Vol. 74, no. 216. Reading, Pennsylvania. Associated Press. November 8, 1932. p. 3. Retrieved September 3, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Help Reaches Liner In Disabled Storm". Bluefield Daily Telegraph. Vol. 40, no. 235. Bluefield, West Virginia. Associated Press. November 8, 1932. p. 7. Retrieved September 3, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Storm Ravages Caribbean Area". Indiana Evening Gazette. Vol. 29, no. 6. Indiana, Pennsylvania. International News Service. November 8, 1932. p. 7. Retrieved September 6, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Damage Heavy". Montana Butte Standard. Vol. 70, no. 30. Butte, Montana. Associated Press. November 7, 1932. p. 2. Retrieved September 3, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "American Schooner Wrecked By Storm". The Lincoln Evening Journal. Lincoln, Nebraska. Associated Press. November 7, 1932. p. 11. Retrieved September 3, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Second Ship Is In Distress With Rudder Disabled". Montana Butte Standard. Vol. 70, no. 31. Butte, Montana. Associated Press. November 8, 1932. p. 6. Retrieved September 3, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Ryan, James A. (November 7, 1932). "Coastline of Colombia Hit By Hurricane". Belvidere Daily Republican. Vol. 38. Belvidere, Illinois. International News Service. pp. 1, 4. Retrieved September 3, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Central America Is Devastated By Hurricane". The Daily Courier. Vol. 60, no. 307. Connellsville, Pennsylvania. International News Service. November 7, 1932. p. 1. Retrieved September 3, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "West Cuba And Yucatan In Peril By Fierce Storm". The Helena Independent. Vol. 67, no. 322. Helena, Montana. Associated Press. November 8, 1932. p. 7. Retrieved September 6, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Sea Wall Collapses". The Brownsville Herald. Vol. 1, no. 104. Belvidere, Illinois. Associated Press. November 2, 1932. p. 17. Retrieved September 3, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Flights Canceled". The Kingsport Times. Kingsport, Tennessee. Associated Press. November 9, 1932. p. 1. Retrieved September 7, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Jamaica Hit By Hurricane". Florence Morning News. Vol. 24, no. 67. Florence, South Carolina. Associated Press. November 9, 1932. pp. 1, 6. Retrieved September 7, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Hurricane on Caribbean Sea Hits Freighter". The Coshocton Tribune. Vol. 24, no. 67. Coshocton, Ohio. Associated Press. November 7, 1932. p. 1. Retrieved September 3, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "$4,000,000 Loss In Kingston". Alton Evening Telegraph. Alton, Illinois. Associated Press. November 10, 1932. p. 2. Retrieved September 7, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "About the Cayman Islands". caymankaivacations.com. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ Wells, David (October 2018). "A Brief History of the Cayman Islands" (PDF). Cayman Islands Government Office UK. p. 40. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ "The Balboa". Adventure Dives. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ "Cuba In Danger". Montana Butte Standard. Vol. 70, no. 30. Butte, Montana. Associated Press. November 7, 1932. p. 2. Retrieved September 3, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Hurricane Warning Issued at Havana". Ames Daily Tribune-Times. Vol. 66, no. 110. Ames, Iowa. United Press International. November 8, 1932. p. 1. Retrieved September 6, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Twelve Die As Hurricane Hits Eastern Cuba". Warren Times-Mirror. Vol. 33. Warren, Pennsylvania. Associated Press. November 9, 1932. p. 1. Retrieved September 6, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Christopher Landsea; et al. (2003). "Hurricane Vulnerability in Latin America and The Caribbean" (PDF). NOAA. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved October 15, 2007.