1919–1922 Philippine financial crisis

The 1919–1922 Philippine financial crisis resulted as a consequence of an economic crisis which began in 1919 along with the mismanagement of the Philippine National Bank. Due to the Wood-Forbes Mission in 1921, there were questions among Filipino politicians on who should take responsibility.[1]

Because of this, the Philippine Legislature experienced a leadership crisis resulting to the resignation of House Speaker Sergio Osmeña on December 16, 1921, and Senate President Manuel L. Quezon on January 10, 1922.[2]

Economic reforms implemented during the administration of Governor General Leonard Wood helped the Philippine economy recover from the crisis. By 1923, the Legal Reserve Fund of the Philippine government was restored.[3] The cabinet crisis of 1923 fundamentally broke out as a result of disagreements between Philippine government officials and the government reform agenda of the governor general.[4]

Overview

[edit]Philippine National Bank

[edit]The Philippine National Bank was established in 1916 with the aim of maintaining the gold exchange standard. To support this, currency reserves were created. However, these reserves, which came from the New York branch of the bank, were later transferred to Manila and used to provide loans to agricultural companies for export.[1][5] Since the Philippines was unaffected by World War I, capital formation intensified and prices increased for Philippine commodities. Eventually, the pricing bubble of these commodities burst after the war.[6]: 231-232 Due to the collapse of commodity prices immediately after World War I, this caused a major loss for the companies. This diversion of funds led to the depletion of the reserves, rapid inflation, and ultimately a financial crisis for the National Bank from 1919 to 1922.[1]

The crisis was at its height in 1921. The shift towards pre-war normalcy significantly affected the Philippines in 1921, leading to a sharp decline in the prices of key cash crops: abaca fell from ₱50 to ₱16, sugar from ₱50 to ₱9, and copra from ₱30 to ₱10. Internal revenue collections dropped from ₱52,279,177.22 in 1920 to ₱41,833,832.11 in 1921, creating a large budget deficit. The national bank struggled to provide government funds as it lent money to private borrowers, mainly in the sugar industry, leading to defaults. This triggered a severe fiscal crisis for the national government.[7]

Wood-Forbes Mission of 1921

[edit]

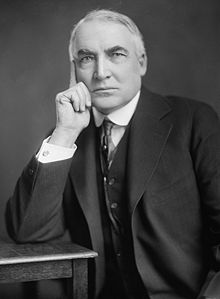

In December 1920, President Woodrow Wilson delivered a speech in U.S. Congress over which he stated that the Philippines has met the requirements for independence stipulated under the Jones Law of 1916. In 1921, the newly elected U.S. president Warren G. Harding was highly skeptical of Wilson. Harding, who was formerly a chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on Territories and Insular Affairs (1929–1946), knew that the Philippines was already in a deep financial crisis. After seeking advice from several experts, he sent an investigative team headed by Major General Leonard Wood, who was chosen as the first candidate as Governor General of the Philippines, and William Cameron Forbes, former governor general of the islands from 1909 to 1913, was appointed as the other member of the mission.[1]

The U.S. Secretary of War, John W. Weeks, instructed General Leonard Wood to investigate the financial stability of the Philippine government and the impact of the Filipinization policies implemented under Governor General Francis Burton Harrison. The Bureau of Insular Affairs (BIA) in the U.S. played a crucial role in gathering information from the Philippines to assist in this investigation. Weeks emphasized the ability of the Philippine government to maintain stability without U.S. aid.[1] The mission departed from the U.S. to the Philippines in April 1921.[1][8]

Leadership crisis

[edit]

Leonard Wood was inaugurated Governor General of the Philippines in October 1921.[9] Francis Burton Harrison, former governor-general, wrote to Senate President Manuel L. Quezon that same month about their missed chance to avoid a disaster that affected their administration, linking it to the Philippine National Bank situation. He noted that American critics in the Philippines had a limited perspective. Quezon shared some blame for allowing House Speaker Sergio Osmeña's autocratic style to persist, either knowingly or tolerantly. The Philippine Senate also played a role in confirming appointments while Quezon was ill. The senate ceated a committee whose function was to confer with Wood regarding with appointments. Senator Rafael Palma served as acting senate president during that time.[10]

Because of the Wood-Forbes report, the president of the Philippine National Bank, General Venancio Concepcion, was indicted for corruption. Additionally, the report also detailed that government funds held in other banks were transferred to the National Bank, except for trust funds held with the United States. The bank gained control over these funds and the Currency Reserve Fund, leading to a significant influx of foreign exchange funds. The bank then made substantial profits from exchange transactions, a portion of which was lent to speculative enterprises which caused serious doubt on the bank's transactions.[1]

The report was also used by the Partido Democrata to attack the ruling Nacionalista Party and to criticize the Harrison administration.[1]

After the Wood-Forbes report was published, Quezon made a public campaign in support for a collective leadership to ensure he was consulted on important matters, especially appointments, to prevent the Philippine National Bank's near-bankruptcy. He informed Osmeña that since the Jones Act's implementation, most legislators and cabinet members had let Osmeña control legislation and public affairs, with all major measures receiving his approval and appointments being made with his consent.[11]

On 16 December 1921, senators and representatives held separate meetings, followed by a convention the next day where leadership issues arose without resolution. Osmeña stepped down from his speakership to gain a vote of confidence. On 18 December, representatives backed a resolution supporting Osmeña, while senators did not act.[12]

There were attempts made for reconciliation such as the formation of the Council of Ten.[13] This was to conciliate the two. However, due to its members being pro-Osmeña lawmakers, Quezon resigned to the senate presidency in January 10, 1922. Osmeña begged Quezon to withdraw his resignation but Quezon refused. Osmeña then resigned as Nacionalista Party leader due to the severity of the leadership crisis.[14]

Response

[edit]

During the financial crisis, the cooperation between the Filipino elites and American authorities fell apart. The Bureau of Insular Affairs tried to address issues with the Gold Standard Fund, while banking officials expanded lending irresponsibly, worsening the crisis and undermining the Philippine National Bank's legality.[15]

Reforms by the Governor General

[edit]Filipino politicians closely followed American politics due to its impact on Philippine independence. They expected Governor General Wood to return to the U.S. soon, believing short-term cooperation with him was beneficial. This was evident in how easily Wood's financial reform agenda passed in the Philippine Legislature. However, they disagreed with his fiscal reform and neoliberal development plans, planning to wait him out. As Wood dedicated more time to his agenda and did not return for the 1924 elections, Filipino leaders had to confront his reforms and defend their own development framework.[16]

The topic of fiscal and developmental reforms was very controversial. Governor Wood opposed the national government's involvement in private enterprise, unlike his predecessor. He called for the sale or dismantling of government corporations from the Harrison administration, citing the financial burden they placed on public funds. By 1922, the government had spent about ₱70 million on these corporations, significantly exceeding the average annual budget before the 1921 crisis.[17]

If Osmeña controlled the Philippine National Bank, then Senate President Manuel Quezon was seen as the main supporter of the Manila Railroad Company (MRC). Speaker Osmeña, a strong political rival of Quezon, suggested that Quezon had been using the MRC for political favors. Wood had concerns about selling these corporations quickly because he believed they were used by top Filipino politicians for political patronage. Claro M. Recto of the Partido Democrata accused the Nacionalista Party of using the bank for political gain. An American journalist claimed the bank granted loans to Nacionalista politicians. The bank's president, seen as unqualified, was arrested for irregular transactions, though Speaker Osmeña was not directly tied to any wrongdoings.[18]

PNB board members were further investigated by the Wood administration including Vicente Madrigal, Senator Vicente Singson Encarnacion, and Manila Mayor Ramon J. Fernandez due to their approval of speculative loans made by the bank.[19]

In 1922, Wood proposed selling sugar centrals debtors, but Quezon ultimately decided against it.[20]

Response to the Quezon-Osmeña split

[edit]Quezon and his followers challenged the one-man leadership of Osmeña describing him as an "inefficient and corrupt dictator".[1] Debates between Osmeña and Quezon lasted until February 1922.[13] That same month Quezon, along with his supporters from the House of Representatives and Senate, created a new party, the Partido Nacionalista Colectivista.[21] The Nacionalista Party, as a result, was split in two: the Colectivistas led by Quezon and the Unipersonalistas led by Osmeña.[1]

Following the Quezon-Osmeña conflict in 1921-1922, Governor-General Wood faced opposition from Quezon and his supporters. Shortly after taking office, he became the target of political attacks for seeking advice from Sergio Osmeña on appointments, which was common practice. This upset Quezon's Senate followers, who believed Wood should have consulted them instead. Wood further antagonized Quezon and his followers in the Philippine Senate.[22]

The issue calmed when the Philippines Herald reported that Wood agreed to include legislative leaders in future discussions about appointments, reflecting the rising tensions between Quezon and Osmeña.[22]

Criticism against Leonard Wood

[edit]

In March 1922, because of the split in the Nacionalista party led to only five bills being passed during the regular legislative session. Due to financial needs, Wood called for an extra session. Osmeña requested to consider private bills from the regular session. Wood agreed, and most government measures were enacted and signed into law.[23]

The Quezon-Osmeña rift made some government plans to be set aside. Fifty private bills were sent to the Governor General for approval, but Wood vetoed sixteen of them. One bill aimed to cancel a new assessment law crucial for the budget, while the others were poorly written or politically motivated amidst a financial crisis in the Philippines. Wood faced criticism from Maximo M. Kalaw writing for the Philippine Herald. He accused him of misusing his veto power and claimed that his actions undermined the Jones Act. Kalaw argued that since Wood was not elected, his vetoes were improper unless supported by the people. He pointed out that Wood should have sought legislative advice, as the cabinet did not represent the will of the people. La Nacion, a newspaper ran by the Partido Democrata, defended Wood and stated that he informed the Legislature regarding the reason of not signing those bills.[23]

The Philippine Herald later showed an editorial depicting a cartoon of Wood killing a Filipina. Wood was painted as an autocrat during his years of service as governor general.[24]

Aftermath

[edit]1922 general elections

[edit]Quezon's Colectivista party won against Osmeña, with Quezon being elected Senate President.[1]

Speaker for the House of Representatives

[edit]In 1922, Claro M. Recto of the Partido Demacrata withrew himself from the election for the speakership. Both Manuel Roxas and Mariano Jesús Cuenco were deadlocked. Due to the Nacionalistas and Colectivistas forming a coalition, Cuenco then withdrew from the election. As a result, Roxas was elected as Speaker.[25]

Restoration of the Philippine economy

[edit]

Between 1921 and 1922, Governor Wood's request for government economy cut the budget from $52 million to $37.5 million without affecting public works, school construction, or public health services. The U.S. Congress allowed a second increase in the Philippine Islands' debt limit. Consequently, the peso gradually returned to par.[3]

On April 29, 1922, the Board of Control decided that the PNB should quickly sell its holdings. No more loans were to be given to sugar centrals unless needed for crop shipments. The Bank was not to risk depositors' money with long-term loans. The PNB was to become an agricultural bank when possible. The general manager of the PNB, E. W. Wilson, believed his bank had an important role in the Philippines' development. However, his refusal to follow orders led to his resignation by the Board of Control and the Bank's Board of Directors. Despite this, Wilson and others helped save the national bank as Osmeña and Quezon changed their stance. In May 1923, Wood announced the bank would continue as a regular commercial institution with a safer approach.[20]

By June 1923, the government’s Legal Reserve Fund was restored, providing gold backing for the peso. Economy was emphasized that year. Wood appreciated the public's confidence in the government and its leaders, particularly as his administration needed to raise the national debt.[3]

However, the sale of government corporations by Wood was unsuccessful due to poor market conditions. Analysts in 1923 expected a recovery soon, so he had to postpone asset liquidation until prices improved.[26]

Cabinet crisis of 1923

[edit]The cabinet crisis of 1923 was believed to have begun with the reinstatement of Detective Ray Conley by the Governor General, which resulted to the mass resignation of Filipino government officials.[26] However, the cause of the cabinet crisis was due to the 1921 financial crisis.[27] According to the self-confession written by Senate President Quezon, he wanted to protect the Philippines' "economic heritage" over which Wood "wanted to hand over to American capitalists."[26]

The cabinet crisis emerged from a conflict between Governor Wood and senior Filipino officials over their differing government and development plans. This clash arose from their opposing views and the political and economic factors related to Wood's reform agenda. Wood believed strongly in an ideal government, driven by a desire to prevent corruption and ensure efficient governance, especially during a crisis. In contrast, Filipino politicians saw Wood as a temporary overseer of their government, as guaranteed by the Jones Law of 1916. They wanted his agenda to focus on Filipino interests rather than American benefits and were skeptical about his plans to sell government assets to American investors, believing the economic crisis would soon end as early as 1924.[4]

Impact

[edit]The political battles over the PNB and the Currency Reserve Fund directly impacted issues related to land, labor, and wages in various regions like Visayan sugar plantations, Luzon tobacco factories, and Bicol ports.[6]: 261

Land inequality

[edit]The influx of capital during the wartime boom led to significant land accumulation by wealthy landowners for agricultural products like sugar and copra. This resulted in smaller landholdings diminishing, increased usury, and a shift towards tenancy farming. After the 1921 financial crisis, large landholders received the redistributed land instead of smaller owners or tenants, while agricultural workers faced wage cuts and layoffs.[6]: 261 The inequality of land distribution resulting from the postwar economic crisis was described by Carlos Bulosan in his seminal work, America is in the Heart, where he narrated his experiences as a child of a tenant farmer during the early 1920s.[6]: 265

Unemployment

[edit]According to the report of the Philippine Bureau of Labor in March 1921, the financial crisis greatly affected the majority of municipalities in the islands. In Manila, 6,585 Filipino workers became unemployed, most of them worked in cigar factories. During the first six months in 1921, there was a total of 20 labor controversies throughout the islands. These affected more than 17,000 Filipino workers. Seventeen of these controversies developed into strikes demanding wage increases.[28]: 217

Sugar industry

[edit]Despite exporting a larger quantity of sugar in 1922 compared to 1921, the overall value remained similar due to low prices at the beginning of the year. This was attributed to the acute financial condition of the islands, forcing planters to sell sugar at a loss to secure immediate financial assistance. However, as the year progressed, the global sugar market improved, leading to higher prices for Philippine sugar and enabling planters to achieve profitability. By the end of 1922, the sugar market conditions were favorable, with reports indicating a continued improvement in the sugar situation in 1923.[29]: 263

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Nagano, Yoshiko (2001). "The Crisis of the Philippine National Bank and Its Political Consequences: 1919-1922". Southeast Asia: History and Culture. 2001 (30): 3–24. doi:10.5512/sea.2001.3.

- ^ Gripaldo 1991, pp. 171, 174.

- ^ a b c Onorato 1966, p. 356.

- ^ a b Ybiernas 2014, p. 84.

- ^ Wolters, Willem (July 2016). "State and Finance in the Philippines, 1898–1941: The Mismanagement of an American Colony. By Yoshiko Nagano. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, 2015. Pp. xiv + 248. ISBN 10: 9971698412; ISBN 13: 978-9971698416". International Journal of Asian Studies. 13 (2): 256–259. doi:10.1017/S1479591416000152. ISSN 1479-5914.

Furthermore the officials allowed the PNB to transfer funds from the US to the Philippines. The PNB did this by selling drafts on the New York agency of the bank. These funds were then used to finance loans to businesses in the island, both American and Philippine entrepreneurs and corporations. The operations depleted the American part of the Gold Standard Fund.

- ^ a b c d Lumba, Allan (2013-07-25). "Monetary Authorities: Market Knowledge and Imperial Government in the Colonial Philippines, 1892 - 1942". University of Washington.

- ^ Ybiernas 2014, p. 79.

- ^ Gripaldo 1991, p. 165.

- ^ Gripaldo 1991, p. 168.

- ^ Gripaldo 1991, p. 169.

- ^ Gripaldo 1991, p. 170.

- ^ Gripaldo 1991, p. 171.

- ^ a b Gripaldo 1991, p. 173.

- ^ Gripaldo 1991, p. 174.

- ^ NAGANO, YOSHIKO (1999-12-01). "Politics and Philippine Banking During the American Period". Philippine Political Science Journal. 20 (43): 61–82. doi:10.1080/01154451.1999.9754205. ISSN 0115-4451.

- ^ Ybiernas 2014, p. 81.

- ^ Ybiernas 2014, p. 80.

- ^ Ybiernas 2014, p. 82.

- ^ Ybiernas, Vicente Angel S. (2012). "Governor-General Leonard Wood's neoliberal agenda of privatizing public assets stymied, 1921-1927". Social Science Diliman. 8 (1).

- ^ a b Onorato 1966, p. 355.

- ^ Gripaldo 1991, p. 175.

- ^ a b Onorato 1966, p. 357.

- ^ a b Onorato 1966, p. 358.

- ^ Onorato 1966, pp. 358–359.

- ^ Retizos, Isidro L.; Soriano, D. H. (1957). Philippines Who's who. Capitol Publishing House.

- ^ a b c Ybiernas 2014, p. 83.

- ^ Ybiernas, Vicente Angel S. (2007). "Philippine Financial Standing in 1921 The First World War Boom and Bust". Philippine Studies. 55 (3): 345–372. ISSN 0031-7837. JSTOR 42633919.

- ^ U.S. Department of Labor (1923). Monthly Labor Review.

- ^ Commerce, United States Bureau of Foreign and Domestic (1923). Commerce Reports. Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce, Department of Commerce.

Sources

[edit]- Gripaldo, Rolando M. (1991). "The Quezon-Osmeña Split of 1922". Philippine Studies. 39 (2): 158–175. ISSN 0031-7837. JSTOR 42633241.

- Onorato, Michael (August 1966). "Leonard Wood: His First Year as Governor General, 1921-1922" (PDF). Asian Studies: Journal of Critical Perspectives on Asia. 4 (2): 353–361.

- Ybiernas, Vicente Angel (2014-06-30). "The Politics and Economics of Recovery in Colonial Philippines in the Aftermath of World War I, 1918-1923". Asia-Pacific Social Science Review. 14 (1). doi:10.59588/2350-8329.1022. ISSN 2350-8329.